19

- Society for Acute Medicine

- Acute Med UK

- Cork Emergency Medicine Handbook

- MPS Factsheets Urgent Care Clinicians

- Guidance for commissioning integrated urgent and emergency care

- RCGP Centre for Commissioning

- Primary Care Foundation

- Out of Hours and Unscheduled Primary Care: Making it safer MPS Sep 2011

Emergency care Red Flags

1.CARDIAC CHEST PAIN requires emergency 999 blue light ambulance admission.

If the ambulance is going to be delayed then you attend urgently

2. STROKE 999 FAST

3. SILENT ASTHMATIC

When patients’ relatives report that the patient’s asthma has suddenly improved because they have gone quiet and their breathing is much shallower they may well be describing a very serious deterioration in asthma.

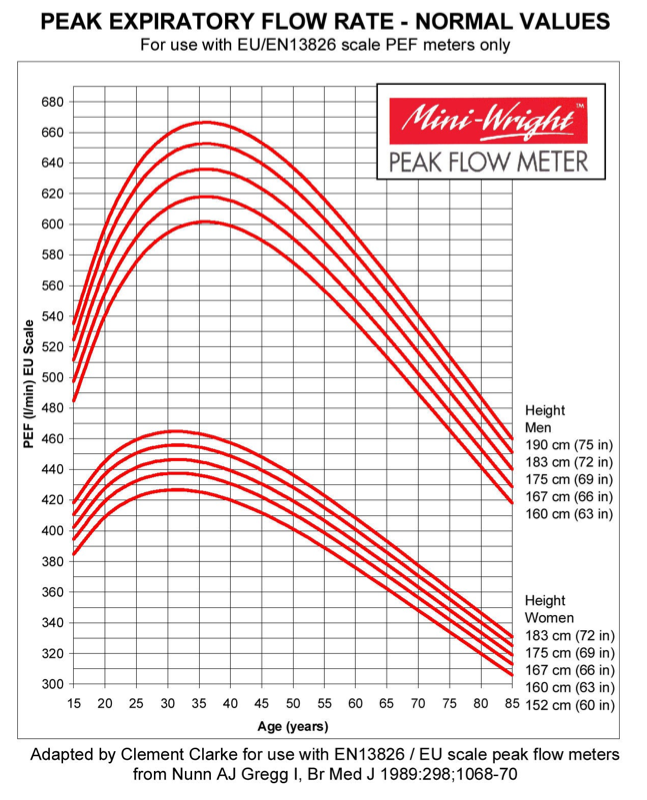

Asthma severity is often under-estimated. Always check Peak Flow. Over use rather than under use steroids. Don’t be reluctant to admit children.

Stridor Do not manage stridor in children over the telephone – GO AND SEE THE CHILD

4. FAMILY CONCERN

If you are given telephone advice and the family remain clearly concerned about the patient and are unhappy with this then reconsider the decision not to see the patient and assess them face to face.

Sometimes the history given over the telephone does not marry with the condition of the patient once seen.

5. If a patient at home is considered to be ill enough to require oxygen, admit for full assessment.

6. Make proper clear legible notes after every contact.

7. Patient safety and risk takes priority over local hospital bed difficulties. Your role is to make a clinical decision not to be a bed manager.

| Level | Acuity | Treatment & Assessment Time | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 level Acuity | |||

| 1 | Emergent | Immediate | Cardiac Arrest Anaphylaxisrespiratory distress coma poisoning |

| 2 | Urgent | 20 min – 2hr | non-cardiac chest pain severe abdo pain |

| 3 | NonUrgent | 2-4 hr | strains sprains earache |

| 4 level acuity | |||

| 1 | Emergent | Immediate | Cardiac Arrest Anaphylaxis |

| 2 | Urgent | 15-30 min | major fracturessexual assault |

| 3 | SemiUrgent | 30-60 min | alcohol intoxication abdominal pain |

| 4 | NonUrgent | 1-2 hr | minor burns or bites |

| 5 level acuity | |||

| 1 | Critical | Immediate | Cardiac Arrest Anaphylaxis |

| 2 | Unstable | 5-15 min | major fracturesod |

| 3 | Potentially Unstable | 30-60 min | alcohol intoxicationabdominal pain |

| 4 | Stable | 1-2 hr | cystitis minor bites |

| 5 | Routine | 4 hr | suture removal |

Doctors bag

The bag should be lockable and not left unattended during home visits. If left in the car the bag should be locked and kept out of sight, preferably locked in the boot.

Most pharmaceuticals should be stored between 4-25 degrees. Ideally the doctor’s bag should be silver in colour as this keeps drugs significantly cooler than the traditional black bag. It is useful to keep a maximum and minimum thermometer in the bag to record the extremes of temperature.

Remember that bright light can inactivate some drugs so keep the bag closed when not in use.

The origin, batch numbers and expiry dates of all drugs should be recorded and the drugs checked regularly to ensure they are still in date and usable.

1. Remember to stock a good supply of water for injection, syringes and needles

2. Check periodically that the drugs are not past the expiry date

3. Keep a special book to list the controlled drugs

4. Particularly important are adrenaline for anaphylaxis, diazepam for convulsions (including Stesolid for rectal use in children), glucagon for hypoglycaemia in diabetics and Lv. hydrocortisone and aminophylline/salbutamol for use in patients with severe asthma.

Frusemide for cardiac failure is essential and for renal colic, acute gout, backache or severe sprains seen on a home visit an injection of Voltarol is highly effective (assuming no history of peptic ulceration or drug-induced asthma attacks)

5. Many GPs use a separate drugs bag for the above and a second bag for essential forms (prescriptions, sickness certificates, notepaper, continuation cards, temporary resident forms, etc.) and equipment (stethoscope, auriscope, ophthalmoscope,sphygmomanometer, thermometer, gloves, airway, etc.). How much extra equipment is carried for emergencies (nasal packing equipment, resuscitation equipment, obstetric equipment, etc.) depends on the expertise of the GP the nearness or otherwise ofthe local Casualty and the special features and situation of the GP’s practice

Accu-chek Mobile – May not in fact be suitable for multi-patient use?

Thermofocus Non-Touch Thermometer”

Optyse Lens Free Pocket Opthalmoscope

Suppliers

http://www.firstaidwarehouse.co.uk/

http://www.pulsemedicalstore.co.uk

http://www.medisupplies.co.uk/acatalog/Diagnostics.html

OOH formulary

1 Follow local MM guidelines

2 Quantities prescribed/supplied should be sufficient to provide a full course to treat the presenting condition but no more.

Prescriptions for patients running out of their usual repeat medications should not exceed 7 days.

3. Refer to the Guidelines for the Management of Drug & Alcohol Users at Baycall for guidance on requests for addictive medicines including methadone and Subutex®.

4. Benzodiazepines can only be prescribed in the following circumstances:

Bereavement

As an adjunct to simple analgesia in severe acute spinal pain

Psychiatric emergencies

5. The out of hours clinician will consider the urgency of the situation and decide the need to:

i. Give advice only and not supply any prescription or medicine.

ii. Refer the patient to a community pharmacy for advice or self-treatment

iii. Supply the patient with a prescription

iv. Supply a medicine directly

6. When a supply of medicine is given to the patient directly, it will be in its original container, labelled accurately and legibly and a Patient Information Leaflet given. The patients will be informed of where to seek any additional advice.

7. Doctors will use FP10 prescription forms if it is necessary to supply a patient with a prescription to take to a community pharmacy.

FP10REC forms will be used for all medicines supplied or administered at the centre or in patient’s homes.

8. Patients should pay a prescription charge for medicines supplied out of hours unless the patient is exempt and completes a declaration to this effect. It is not envisaged that money will be collected directly, but by an invoice given to the patient or posted to them.

Items not subject to a prescription charge are:

Contraceptives (i.e Levonelle 2)

Items supplied for ‘immediate treatment’

Items personally administered (Immediate treatment’ means medicines that are given to the patient to take whilst in the OOH centre.)

9 The department does not keep or issue any stock drugs only those needed in medical emergencies —

10 Be aware of location of emergency drugs.

11 Pharmacy -OPENING TIMES -out this a list of local chemists OPENING TIMES and DIRECTIONS

12 Self Care is encouraged. Prescriptions for Calpol etc are positively discouraged. LINK TO ANTIPYRETICS

13 Clinical autonomy is respected but please try to stick to the formulary where possible, prescribe generically and prescribe minimal quantities of drugs to see the patient through their acute illness or enough till the next GP opening times.

We all acquiesce occasionally but patients/parents should be encouraged to purchase or otherwise not purchase clinically inappropriate medications

Kingston orange book core drugs

- Activated charcoal (50g powder)

Adrenaline/epinephrine (1 in 1000, ie 1mg/mL ampoules)

Amoxicillin (250mg capsules or 125mg/5mL suspension)

Aspirin (300mg soluble tablets)

Benzylpenicillin (600mg vials for reconstitution with water for injection)

Cefotaxime (1g vial for reconstitution with water for injection)

Chlorphenamine/chlorpheniramine (10mg/mL injection)

Ciprofloxacin (500mg tablets)

Diamorphine (5mg or 10mg powder in ampoules for reconstitution with water for injection)

Diazepam (5mg tablets, 5mg/mL injection as Diazemuls for IV and diazepam for rectal administration 2-4mg/mL)

Diclofenac (25mg/mL injection, 25mg tablets)

Dihydrocodeine (30mg tablets)

Erythromycin (250mg tablets or 125mg/5mL suspension)

Fibrinolytic drugs (depending on local arrangements)

Flamazine cream

Flucloxacillin (250mg capsules or 125mg/5mL syrup)

Furosemide/frusemide (10mg/mL injection)

Glucagon (1mg vial with prefilled syringe containing water for injection)

Glucose (50% solution; to dilute this carry a 50mL syringe and large bore needle)

Glucose (Hypostop gel or glucose tablets or glucose containing drink)

Glyceryl trinitrate (as an aerosol that delivers 400micrograms/metered dose)

Haloperidol (1mg/mL liquid or 5mg tablets)

Hartmann’s solution (sodium lactate intravenous infusion, compound 500mL).

Hydrocortisone (100mg powder as sodium succinate for reconstitution)

Ibuprofen (100mg/5mL suspension)

Ipratropium bromide (250micrograms/mL nebuliser solution)

Lidocaine/lignocaine (10mg/mL injection))

Lorazepam (1mg tablets, 4mg/mL injection)

Metoclopramide (5mg/mL injection or 10mg tablets)

Naloxone (400 micrograms/mL injection)

Oral rehydration salts (eg Dioralyte or Rehidrat)

Oxygen

Paracetamol (500mg tablets and 120mg/5mL paediatric oral solution or suspension)

Phenoxymethylpenicillin (125mg/5mL oral solution)

Prednisolone (5mg tablets preferably soluble)

Procyclidine (5mg/mL injection)

Salbutamol or terbutaline metered dose inhaler and salbutamol (1mg/mL nebules) or terbutaline (2.5mg/mL nebuliser solution)

Sodium chloride (0.9%; 500mL or 1000mL infusion)

Trimethoprim (200mg tablets or 50mg/mL suspension)

Water for injection

Personally administered drugs

Personally Administered Drugs @ GP Online

| Home visit guidelines | |

|---|---|

| visit recommended | The Terminally ill. The truly house-bound patient, for whom travel to premises by car would cause a deterioration in their medical condition or unacceptable discomfort. |

| visit may be useful | After initial assessment over the phone, a seriously ill patient may be helped by a GP’s attendence even if it is felt appropriate to order an ambulance first. Examples of such situations are: Myocardial infarction Severe Shortness of Breath Severe Haemorrage There will be occasions where the patient or relative will be unsure or have doubts. On these occasions, patients should have a conversation with the duty doctor. |

| visit not usually needed | In most of these cases a visit would not be an appropriate use of the duty doctors’ time, or in the medical interest of the patient Common symptoms of childhood; fevers, colds, cough, sore throat, earache, diarrhoea / vomiting and most cases of abdominal pain. In these instances patients are usually well enough to travel. More accurate diagnosis can also be made with all the examination facilities and equipment available to the doctor at the Primary Care Centre.Adults with common problems such as a cough, sore throat, influenza, general malaise, back pain and abdominal pain should also be encouraged to attend a Primary Care Centre. |

In all cases the doctor must put himself/herself in a position to properly assess the medical state of a patient and thus the need for a house call.

Not having transport is not sufficient grounds on which to base the decision to undertake a home visit. Patients should be encouraged to seek help from neighbours, family or friends or use a taxi to attend a Primary Care Centre.

Why is it better to be seen in a Primary Care Centre?

There are a number of reasons why home visits are only made in circumstances where a patient’s illness makes them unable to travel.

You can be examined in better facilities and in better lighting.

The doctor can use equipment that cannot be carried in the mobile vehicle.

Should you need to be admitted to hospital, this can be quickly arranged from the PCC.

The doctor can see four patients at the PCC in the time it takes to do one home visit. This means we can see all patients promptly and see the most urgent cases more quickly.

NB – triage staff should use discretion after 10pm and consider patient safety in getting to the PCC

In most of these cases, to visit would not be appropriate use of a GP’s time:

Common Symptoms of childhood: fevers, cold, cough, earache, headache, diarrhoea/vomitting and most cases of abdominal pain. These patients are usually well enough to travel by car. It is not necessarily harmful to take a child with a fever outside. These children may not be fit to travel by bus or to walk, but car transport maybe available from friends, relatives or taxi firms. It is not a doctor’s job to arrange such transport.

Adults with common problems, such as cough, sore throat, influenza, back pain and abdominal pain, are also readily transportable by car to a doctor’s premises.

Common Problems in the elderly, such as poor mobility, joint pain and general malaise, would also be best treated by consultation at a doctor’s premises.

However, inspite of the above, some people may feel that due account needs to be taken of a patient’s circumstances and where necessary a visit should be made. This is all the more so when the safety of a child has to be taken into account.

netdoctor.co.uk/home-visits-out-of-hours-care

| Intravenous fluids | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotonic | expand the intravascular compartment | 5% dextrose 0.9% saline Ringers lactate | monitor for fluid overload |

| Hypertonic | greatly expand the intravascular compartment | 10% dextrose 3% saline 5% saline Dextrose 5% lactate Dextrose 0.45% saline Dextrose 0.9% saline |

monitor for fluid overload |

| Hypotonic | cause a fluid shift from the intravascular compartment into the cells | 2.5% dextrose 0.45% saline 0.33% saline | monitor for CVs collapse |

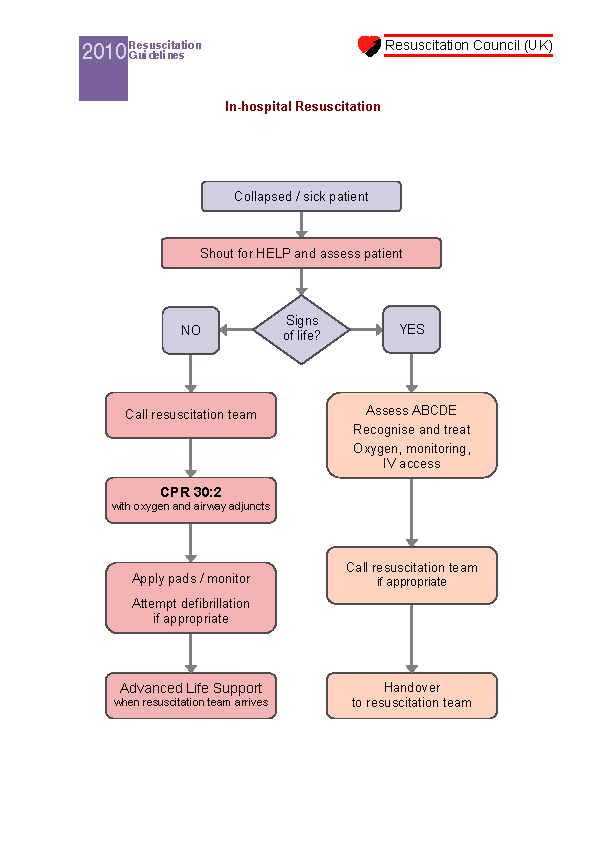

Cardiac arrest

Abrupt/acute cessation of cardiac function. Patient unconcious, not breathing and pulseless.

| 6 H’s and 5 T’sReversible causes of cardiac arrest – consider these in all cardiac arrests and near cardiac arrestsrcpals.com How to use the Hs and Ts in ACLS and PALS | |

|---|---|

| Hypovolaemia | Tablets (drugs, ODs,accidents) |

| Hypoxia | Tamponade |

| H+ ion (acidosis) | Tension pneumothorax |

| Hyperkalaemia / Hypokalaemia | Thrombosis – ACS |

| Hypothermia | Thrombosis DVT/PE |

| Hypoglycaemia (and other metabolic disorders) | Trauma |

Cardiac output must be restored within minutes

Hypoxia is the commonest cause of cardiac arrest in children.

Cardiac arrest – managing the patient who survives NELM

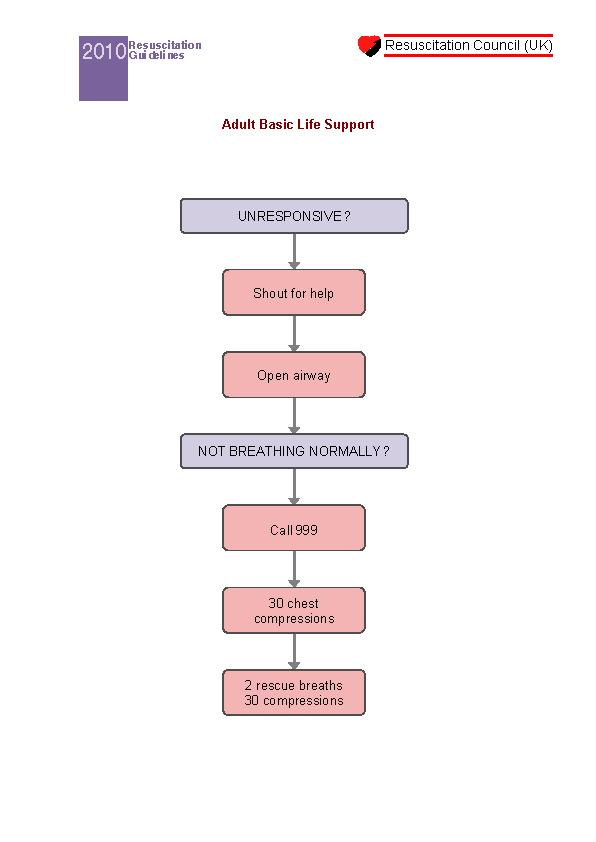

BLS adults

Ensure safety of rescuer and victim.

Assess responsiveness: gently shake shoulders and shout “Are you all right?”.

1/unresponsive

Open Airway: remove obvious obstruction; use head tilt and chin lift. IT neck injury is suspected use jaw thrust.

Check Breathing (max. 10 seconds): look, listen, and feel for chest movements and breath sounds at mouth.

If not Breathing

Give two rescue breaths using mouth-to-mouth ventilation.

Check Circulation (max. 10 seconds): look for any movement of victim; check carotid pulse.

If pulse present

Continue rescue breathing, recheck every minute for signs of circulation.

If no pulse (or unsure if pulse)

Start chest compressions at 100 times a minute, combined with ventilation (30 compressions to two breaths).

Mouth-to-mouth ventilation

Open Airway as above. Occlude nostrils. Ensure a tight seal around the patient’s mouth.

Gently Breathe into the patient for about 1.5-2 seconds, ensuring the chest wall rises.

If the chest wall does not move, reassess the airway, adjusting head tilt as necessary. Too vigorous a breath will force air into the stomach (so increasing risk of aspiration, vomiting, etc.).

A disposable mouth-guard provides a barrier between you and the victim but does not compromise ventilation. This is just a compact plastic sheet with a filter in the middle. If you possess a pocketmask, you can perform mouth-to-mask ventilation instead. Some masks are re-usable and oxygen can be attached if you carry it. There is a one way valve so that you do not breathe in expired air.

Chest compressions

Place the heel of one hand two finger breaths above the xiphisternum and place the other hand on top, interlocking fingers if necessary. Compress the chest to a depth of 5-6 cm, keeping the arms straight and vertically above the chest. The rate is 100n-120 compressions per minute.

Two rescuers: 15 compressions to two breaths

One rescuer: 5 compressions to one breath

Continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) until the victim shows signs of life, someone takes over from you, or you are physically exhausted.

if rescuer unable to give ventilation then compression only cpr should be given

Oct 06 2010 Agonal respirations in an unresponsive patient indicate cardiac arrest

- youtu.be/IJaTC2rbVbM

- youtu.be/C_p-KSB6bJM

- youtu.be/Mf8EkVnOl0c

- youtu.be/XV11kplLoxw

- youtu.be/q-1T5AXDVPo

Chin lift / airway management

Airway Management ambulance technician

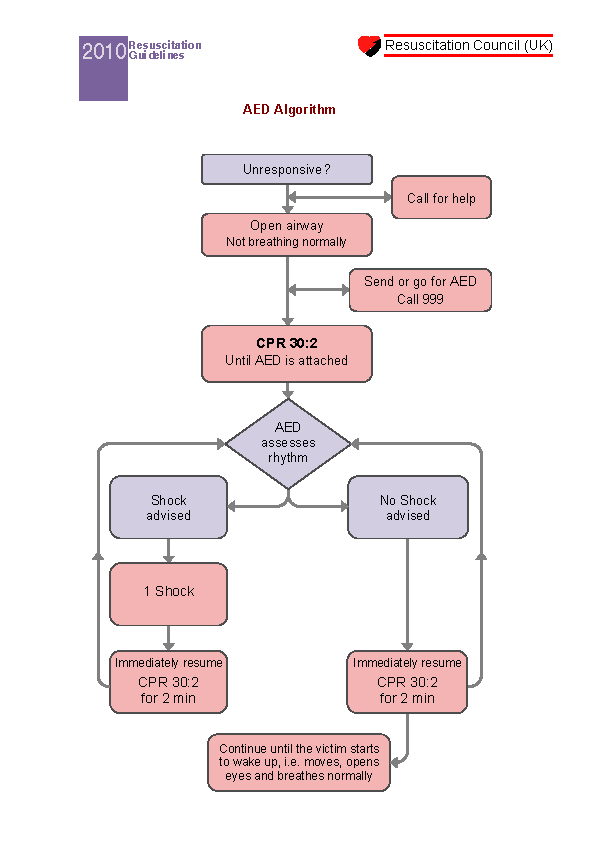

AED adults and children over 8

continue chest compressions while device is charging – do not interrupt for >5 seconds

ILS and ALS

- http://youtu.be/AnTyPtVkAbg

- http://youtu.be/XV11kplLoxw

- http://youtu.be/oDvlb62Mrt4

- http://youtu.be/KCLpXtcQdo8

- http://youtu.be/V-wSWzmxWl4

- http://youtu.be/rHCD2iXNfMw

- http://youtu.be/q6_tAyZwXrk

- http://youtu.be/7n80ejhnt2g

- http://youtu.be/vaF0dgfvtbo

- http://youtu.be/-mFuts2i0bw

- http://youtu.be/MpMnpdEPAHY

- ALS ILS Courses aid-training.co.uk

Anaphylaxis

- hacking-medschool/anaphylaxis-immunology-and-allergy

- anaphylaxis.org.uk

- Anaphylaxis presentation Onmedica – registration needed

- rural health west march 2011 anaphylaxis

Follows the introduction of an antigen by injection as a insect sting, vaccine, or drug (eg penicillin or iron) foodstuffs (eg shellfish or peanuts) through the mucosa (eg latex).

Cause is not always identified

Clinical features

oedema of the face, tongue and larynx, itching, rash, bronchospasm, pulmonary oedema, hypotension and tachycardia.

Those prone to attacks often have a specific pattern of symptoms that they learn to recognise.

Management

Im emergency treat as below and transfer immediately to hospital.

Delayed reactions can occur and/or symptoms may recur.

Patients should be observed for at least the first 8 hours after the onset of symptoms. If patients present while symptoms persist but are waning, they should be transferred urgently (???) to hospital to assess the need for further treatment.

| Adrenaline by IM injection. | |

|---|---|

| Child under 6 m | 0.05ml (50 micrograms) |

| 6 months-6years | 0.12ml (120 micrograms) |

| 6-12 years | 0.25ml (250 micrograms) |

| Adult andmature adolescent | 0.5mL (500 micrograms) |

Giving adrenaline intravenously is potentially hazardous and should be reserved for patients with immediately life-threatening, profound shock, who can be monitored and in whom IV access can be gained without delay.

High concentration oxygen

| Chlorphenamine IM or slow IV (over 1 min) | |

|---|---|

| Child 1-5 years | 2.5-5mg |

| 6-12 years | 5-10mg |

| adult | 10-20mg |

| Hydrocortisone im slow iv to prevent further deterioration. | |

|---|---|

| Child 1-5 years | 50mg |

| Child 5-12 years | 100mg |

| Adult | 100-500mg |

Inhaled salbutamol if severe bronchospasm.

IV fluids if patient shocked and does not respond to drug treatment – rapid infusion of sodium chloride 0.9%.

Give 20mL/kg of body weight for children, 1-2 litres of fluid for adults – may need to be repeated.

Anaphylaxis adults

Anaphylaxis algorythm adults

Epipens

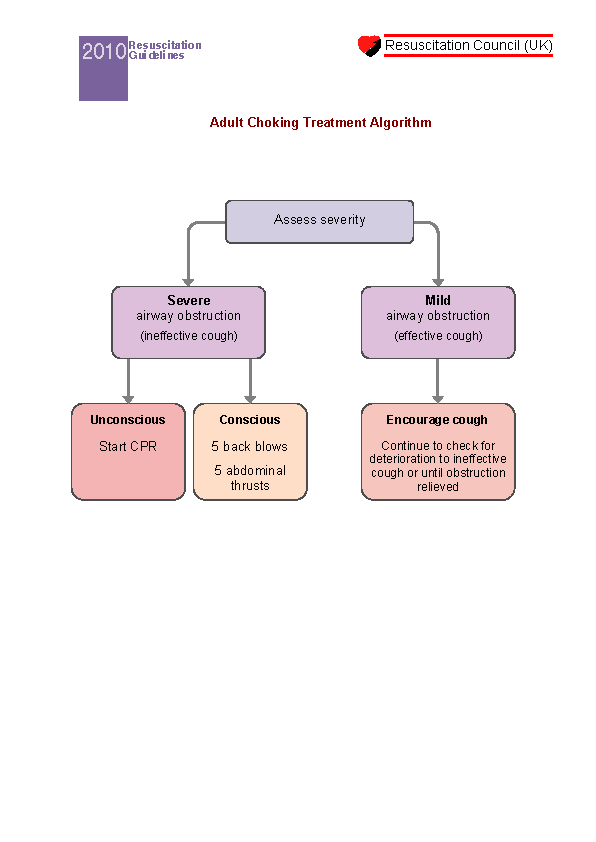

Choking adult

Heimlich and abdominal thrusts

| Cyanosis | |

|---|---|

| Peripheral cyanosis | Bluish colouration of lips tongue and extremities due to excess deoxyhamoglobin. Over 5g/dl must be present before cyanosis apparent ( ie 85% satts or PaO2 less than 60 mm hg)low cardiac output, PVD, increased tissue 02 extraction, extreme cold.Hands and other exposed extremeties are cold and blue. |

| Central cyanosis | – inadequate oxygenation – acute and chronic lung disease PE hypoventilation, decreased inspired O2, polycythaemia, cyanotic CHD with right-to-left shunts. (Fallot’s Eisenmegners complex, transposition of great arteries) Buccal mucosa, tongue, lips (and extremeties) are cyanosed. |

| Differential cyanosis | – cyanosed lower limbs but normal upper limbs with reversed hunt across a PDA. |

| False cyanosis | – methaemoglobinaemia and sulphaemoglobinaemia. |

Pulse Oximetry

Pulse Oximetry Screening for CHD in neonates Lancet Aug 2011

Knowledge of Pulse Oximetry amongst Medical & Nursing Staff Lancet 1994

Simple non-invasive method of monitoring the percentage of haemoglobin which is saturated with oxygen.

Detects hypoxia before the patient becomes clinically cyanosed

A source of light originates from the probe at two wavelengths (650nm and 805nm). The light is partly absorbed by haemoglobin, by amounts which differ depending on whether it is saturated or desaturated with oxygen. By calculating the absorption at the two wavelengths the processor can compute the proportion of haemoglobin which is oxygenated. The oximeter is dependant on a pulsatile flow and produces a graph of the quality of flow. Where flow is sluggish (eg hypovolaemia or vasoconstriction) the pulse oximeter may be unable to function. The computer within the oximeter is capable of distinguishing pulsatile flow from othermore static signals (such as tissue or venous signals) to display only the arterial flow.

Cautions

1. A reduction in peripheral pulsatile blood flow produced by peripheral vasoconstriction (hypovolaemia, severe hypotension, cold, cardiac failure, some cardiac arrhythmias) or peripheral vascular disease. These result in an inadequate signal for analysis.

2. Venous congestion, particularly when caused by tricuspid regurgitation, may produce venous pulsations which may produce low readings with ear probes. Venous congestion of the limb may affect readings as can a badly positioned probe. When readings are lower than expected it is worth repositioning the probe. In general, however, if the waveform on the flow trace is good, then the reading will be accurate.

3. Bright overhead lights in theatre may cause the oximeter to be inaccurate, and the signal may be interrupted by surgical diathermy. Shivering may cause difficulties in picking up an adequate signal.

4. Pulse oximetry cannot distinguish between different forms of haemoglobin.

Carboxyhaemoglobin (haemoglobin combined with carbon monoxide) is registered as 90% oxygenated haemoglobin and 10% desaturated haemoglobin therefore the oximeter will overestimate saturation. The presence of methaemoglobin will prevent the oximeter working accurately and the readings will tend towards 85%, regardless of the true saturation.

5. When methylene blue is used in surgery to the parathyroids or to treat methaemoglobinaemia a shortlived reduction in saturation estimations is registered.

6. Nail varnish may cause falsely low readings.

Not affected by jaundice, dark skin or anaemia.

In patients with long standing respiratory disease or those with cyanotic congenital heart disease readings may be lower and reflect the severity of the underlying disease.

Oximeters give no information about the level of CO2 and therefore have limitations in the assessment of patients developing respiratory failure due to CO2 retention.

Oxygen adults

Oxygen therapy is the treatment for hypoxemia, not breathlessness: oxygen has not been shown to have any effect on the sensation of breathlessness in non-hypoxemic patients. However, failure to administer oxygen to hypoxemic patients can be a life threatening omission.

Assessment of the degree of patient hypoxemia can be made clinically, by looking for the signs of cyanosis and dyspnoea; by simple bedside observations of respiratory rate and pulse oximetry; and ultimately by arterial blood sampling and analysis.

Critically Unwell Patients

Any patient who is critically unwell should be immediately treated with high concentration of oxygen. Oxygen saturation should be checked and recorded, along with the inspired oxygen concentration, on the observation chart, in addition to other vital signs (pulse rate, blood pressure, temperature and respiratory rate).

Initial oxygen therapy is 15 l/min via a reservoir bag and mask

Once stable, reduce the oxygen dose and aim for target saturation range of 94 – 98 %

If oximetry is unavailable, continue to use a reservoir bag and mask until definitive treatment is available

Patients with COPD and other risk factors for hypercapnia who develop critical illness should have the same initial target saturation as other critically ill patients pending the results of blood gas measurements, after which these patients may need controlled oxygen therapy or supported ventilation if there is severe hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia with respiratory acidosis

Cardiac arrest / resuscitation

Use Bag-Valve-Mask during active resuscitation

Aim for maximum possible oxygen saturations until the patient is stable

Shock, sepsis, major trauma, near drowning, anaphylaxis, major pulmonary haemorrhage

Also give specific treatment for the underlying condition

Major head injury

Early intubation and ventilation if comatose

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Give as much oxygen as possible using a bag-valve mask or reservoir mask. Check carboxyhaemoglobin levels.

A normal or high oximetry reading should be disregarded because saturation monitors cannot differentiate between carboxyhaemoglobin and oxyhaemoglobin owing to their similar absorbances.

The blood gas pO2 will also be normal in these cases.

Any Other Hypoxic Patients

Oxygen should only be administered to hypoxic patients – oxygen can have deleterious effects on cardiac, renal and pulmonary function. If the patient is not critically unwell, oxygen should only be administered if the oxygen saturations are less than 98 %.

There are some patients with chronic ventilatory problems who develop chronic type 2 respiratory failure. In this case, CO2 levels rise, resetting the normal physiological control of breathing. These patients rely on relative hypoxia to stimulate breathing, and therefore should be maintained in a state of relative hypoxia (pO2 < 10 kPa) to avoid a fall in minute volume, and therefore an increase in pCO2 and subsequent acute on chronic type 2 respiratory failure with acidaemia.

| chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure | |

|---|---|

| COPD | |

| Cystic Fibrosis | |

| Non-CF bronchiectasis (often in association with COPD or asthma) | |

| Severe kyphoscoliosis or severe ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Severe lung scarring from old TB (eg post thoracoplasty) | |

| Morbid obesity (BMI > 40 kgm-2) | |

| Musculoskeletal disorders with respiratory muscle weakness, especially if on home ventilation | |

| Overdose of opiates, bzds, or other respiratory depressants | |

Patients with, or at risk of, any of the above diagnoses should be treated with controlled oxygen therapy, with the aim of maintaining SaO2 in the range of 88 – 92 %. Arterial blood gases should be obtained as quickly as is feasible.

If chronic CO2 retention is confirmed, oxygen therapy should continue to maintain SaO2 in the range of 88 – 92 %.

If there is no chronic CO2 retention, oxygen therapy should be altered to maintain SaO2 in the range of 94 – 98 %.

Any hypoxic patient with acute CO2 retention should be treated with oxygen to maintain SaO2 between 94 and 98 %. The cause of the acute deterioration must be sought and appropriate treatment commenced.

Oxygen Prescription

Oxygen is a drug and should be prescribed on the TPAR document – the target SaO2 should be clearly documented.

Monitoring and Continued Care

Oxygen saturations should be monitored regularly and documented on the SEWS chart. If the oxygen saturations fall outside the prescribed range the delivery device and/or flow rate should be altered to bring the saturations back into the target range, according to local guidelines.

Postoperative Patients should be given oxygen either by facemask (Hudson mask) or via the nasal route. General anaesthesia predisposes to lung atelectasis which makes patients prone to hypoxia after major surgery. The duration of oxygen therapy will be determined by the magnitude of the surgery and also the patient’s pre existing respiratory status. In general patients should receive continuous oxygen for the first postoperative night after major surgery such as laparotomy or hip or knee replacement. Patients are particularly vulnerable to hypoxic events at night, so it may be necessary to use nocturnal oxygen for a few nights after major surgery in at risk patients (eg those with COPD).

Summary

Give emergency oxygen therapy to all critically unwell patients.

If the patient is not critically unwell, only give oxygen if there is hypoxia.

If the patient is at risk of chronic CO2 retention, aim for SaO2 88 – 92 % initially and get Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs)

If chronic CO2 retention is confirmed, continue oxygen therapy aiming for SaO2 88 – 92 %

If chronic CO2 retention is refuted, continue oxygen therapy aiming for SaO2 94 – 98 %

Ensure that oxygen is prescribed on the TPAR document.

Alter the oxygen delivery device and flow to maintain the target saturation

Dr Tom Fardon Department of Respiratory Medicine, Dr Matthew Checketts, Consultant Anaesthetist December 2008

Recent update – avoid over-oxygenation in acute MI.

Emergency Oxygen in Adults BMJ 2009

| Oxygen Flow Rate (l/min) | Approx % oxygen | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 28 | Nasal Prongs – at normal respiratory rates |

| 4 | 35 | |

| 6 | 45 | Hudson Mask |

| 8 | 55 | |

| 10 | 60 | |

| 12 | 65 | |

| 15 | 70 | |

| 15 | 85-100 | Non-Rebreather Mask(with bag inflated) |

- http://youtu.be/iRniUCT0zWw

- http://youtu.be/wP1_CqcEV5Y

- http://youtu.be/MNzCfO7Z0Fk

- http://youtu.be/2GTE8S95dsA

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jANeuLhiIC8

- http://youtu.be/d_5eKkwnIRs

- Aarons Tracheostomy Page

Anaesthesia / sedation

NHS Bath Sedation in the ED

Intravenous analgesia regime

Use 10 mg morphine made up to 10 ml with water give slowly intravenously in 2 mg aliquots over a few minutes until pain has eased

Don’t forget an antiemetic in adults

Don’t be afraid to use more than 10 mg morphine if the pain isn’t easing

Be aware of side-effects, eg respiratory depression – patient must be monitored

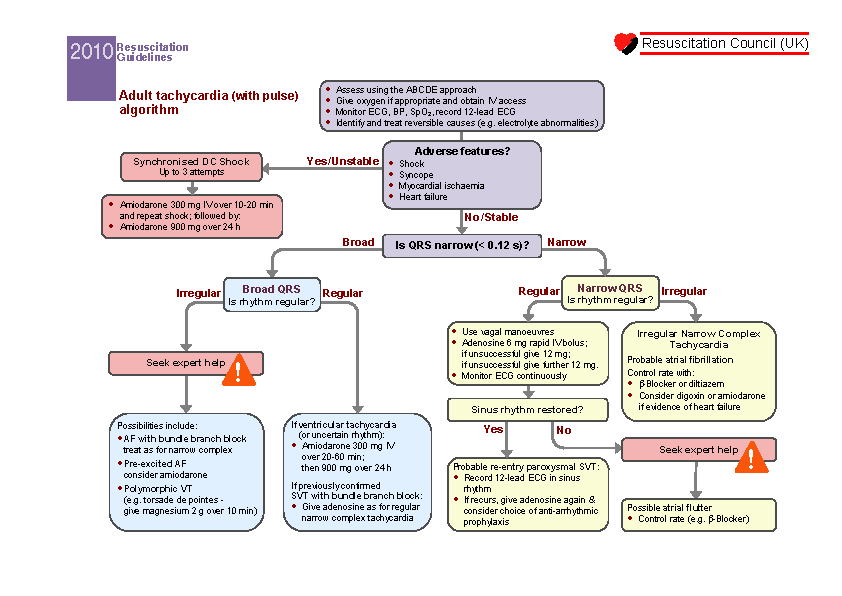

Chest pain and ACS

All patients with chest pain of possible cardiac origin should have an ECG performed and CVS Observations recorded.

For acute infarction/crescendo angina give oxygen and suitable pain relief. (Try Nitrate, Nifedipine then Opiates)

Note Suitable IV access and ECG monitoring should be performed whilst admission is arranged with the Cardiac SHO.

Cardiac patients should be closely observed whilst in the A&E department and during transfer to the ward.

Where myocardial infarction has been diagnosed, patients will normally be commenced on Streptokinase by syringe pump infusion in A&E prior to transfer to CCU, unless it has been contraindicated.

The Cardiac SHO will advise on this in an individual patient basis.

CPR should be performed using the Resuscitation Council Guidelines.

A copy of the most recent European guideline is attached to the wall in Resuscitation. The essential point is that defibrillation should not be delayed, and the patient must he oxygenated using the ABC principles of assessment.

The early phases of acute MI and unstable angina are often indistinguishable.

Their initial management is the same and it has become standard to treat them as a single entity known as ‘acute coronary syndrome’. Patients should be considered as having acute coronary syndrome if they present with:

recent onset of prolonged cardiac chest pain (over 20 minutes) occurring at rest

recent onset of cardiac chest pain on minimal exertion

rapidly worsening chest pain (more frequent, prolonged, severe or easily

provoked, or not responding to their normal glyceryl trinitrate), in someone with known exertional angina.

Referral advice

Patients with an episode of chest pain suggesting an acute coronary syndrome should be transferred to hospital immediately if:

the onset of the pain is within 48 hours (even though the pain has now resolved)

there have been further episodes of pain occurring at rest or on minimum exertion

there are signs of heart failure or other complications.

Patients who have been pain free for more than 48 hours should be referred to be seen at the earliest opportunity, ideally within 2 weeks in a rapid access chest pain clinic).

| ACS | |

|---|---|

| G | GTN sublingually 400 mcg 1-2 sprays |

| A | Aspirin 300 mg chewed or soluble (even if patient taking prophylactic aspirin) |

| M | Metoclopramide 10mg IV over 1-2 minutesDiamorphine and metoclopramide can be mixed in the same syringeIf an oculogyric crisis occurs give procyclidine 5-10mg IM repeated after 20 minutes if necessary |

| M | Morphine Sulphate by slow intravenous injection 10 mg followed by a further 5-10 mg if necessarydiamorphine 5mg IV (2.5mg in elderly or frail patients) at a rate of 1mg/minute Give a further dose of 2.5-5mg after 10 minutes if necessaryif diamorphine causes respiratory depression give 0.4-2mg of naloxone IV every 2-3 minutes to a maximum of 10mg.Cyclimorph (cyclizine plus morphine) is not recommended as cyclizine may aggravate severe heart failure and counteract the haemodynamic benefits of opioids |

| O | Oxygen Highflow non-rebreathing mask (the one with a non-rebreathing bag on the end!) unless COPD |

| N | MoNitor patient |

Avoid injecting drugs intramuscularly as this may:

– increase the risk of bleeding if the patient subsequently receives thrombolysis

-cause muscle damage and rize in plasma enzymes

– delay the onset of effective analgesia; particularly in shocked patients in whom muscle blood flow is greatly reduced

Patients with stable angina or other evidence of ischaemic heart disease or with cardiac risk factors should be given information on what to do if symptoms of an acute coronary syndrome develop. This advice should be shared with the relatives or carers. It helps if a list of emergency numbers is kept accessible in the person’s home.

Practices should have a policy on how to respond to calls to see patients with chest pain.

Determining the cause of chest pain is a common and difficult clinical problem. The main issue is usually to determine whether it is likely to be cardiac or not via careful history of the pain (PQRST) the patients past medical history and risk factors.

Other causes of chest pain include, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal or psychological problems.

Chest pain life threatening: angina, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and aortic dissection.

Chest pain less serious causes: pericarditis, pleurisy, costochondral pain, chest wall pain, esophageal pain, emotional disorders, cervical disc disease, osteoarthritis of the cervical or thoracic spine, abdominal disorders (peptic ulcer, hiatus hernia, pancreatitis, biliary colic), pneumonia and intercostal neuritis (as with herpes zoster).

Women and diabetics may present atypically and less dramatically with myocardial infarctions

Unstable angina pectoris is defined as prolonged (>20 minutes) episodes of angina, angina that occurs at rest, or angina not relieved with three nitroglycerine tablets. Unstable angina is a medical emergency.

Aortic Dissection

Aortic dissection is associated with very severe, tearing or ripping chest pain that radiates to the back and is not affected by position.Syncope associated with chest pain consider in syncope associated with chest pain.Aortic dissection is slightly more likely to occur in pregnant patients and in those with a history of hypertension (and syphilis). Immediate surgical intervention is required. Differential BP Widened Mediastinum

Pericarditis

Severe persistant pain often partially pleuritic aggravated by the supine position and relieved by sitting up.

Pulmonary Embolism

Sharp pleuritic, chest pain and shortness of breath. It may also be accompanied by cough and hemoptysis. Pulmonary emboli are more likely to occur in people who are immobilized, in a leg cast, positive for history of cancer, or people who have recently had a long car or aeroplane trip. The diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism may be supported by Wells criteria

Pleuritis

Pleuritis is chest pain caused by inflammation of the lining of the lungs. This pain is usually described as well localized and knifelike, and it is made worse by changes in position, coughing, sneezing, or breathing. Pleuritic pain may be referred to the shoulder if the diaphragmatic (bottom) pleura is affected. This kind of pain can be initiated by pneumonia, viral syndromes or pulmonary embolism. In acute pneumothorax, there may be a history of recent chest trauma or chronic obstructive lung disease. Pleurisy can be precipitated by pneumonia or a recent viral infection.

Thrombolysis

Thrombolytic therapy reduces mortality in patients who have an acute myocardial infarction. The earlier it is given after symptoms develop the greater the benefit. Thrombolytic therapy should only be given if:you are confident of the diagnosis of acute MI, and a defibrillator and ECG monitor are at hand, and you have had specific training in thrombolytic therapy.

Ideally, a thrombolytic should be given within 60 minutes of the patient calling for help, although it may improve outcome if given up to 12 hours after the onset of symptoms. If there is likely to be a delay of at least 30 minutes before the patient can get to hospital it would be reasonable to start thrombolysis straight away.

The choice of thrombolytic, and the exact protocol for its administration, should be decided at local level in conjunction with the ambulance service and a local cardiologist.

Dissecting thoracic aneurysm

Severe and malignant hypertension

Urgent Referral if BP 180/110

Severely raised arterial blood pressure is life threatening. Management depends on the height of the pressure, the speed at which the pressure has risen and the degree of end-organ damage.

Pressure should be measured while the patient is seated and with the arm supported at the level of the heart.

The frequency of monitoring used to confirm the blood pressure depends on the initial measurement and any additional risks to the patient

| Hypertension Grades | |

|---|---|

| Malignant | 220 or more and/or 120 or more Two readings taken at a single consultation |

| Severe G3 | 180-219 and/or 110- 119 Unless evidence of MH re-measure over 1-2 w |

| Moderate G2 | 160-179 and/or 100 – 109 3-4 w if CVD DM or target organ damage otherwise 4-12 w |

| Mild G1 | 140-159 and/or 90-99 If CVD DM TOD remeasure over 1-2 w otherwise monthly |

| normotensive | 130-139 and/ or 85-89 Reassess yearlyLess than 130 and/ or less than 85 Reassess 5-yearly |

Refer immediately

a blood pressure of 220/120mmHg or more

accelerated malignant hypertension (BP more than 180/110mmHg with signs of papilloedema and/or retinal haemorrhages)

acute cardiovascular complications (eg transient ischaemic attack, LVF, cerebral oedema or dissecting aneurysm)

Refer routinely

sustained BP of 140/90mmHg or more (see table above), and have any one of the following:

non-acute end-organ damage such as mild heart failure or renal impairment

a suggestion of a secondary cause of hypertension; for example, renovascular disease or Conn’s syndrome

resistance to multi-drug treatment (3 drugs or more)

aged under 20 years

aged 20-30 years needing treatment for hypertension.

Timing of the appointment will depend on local arrangements. Start treatment while the patient is waiting for a hospital appointment.

Stroke CVA

Refer urgently 999 for consideration of thrombolysis within 4 1/2 hrs.

| TIPS AEIOU delirium and coma | |

|---|---|

| T | trauma, temp., thiamine |

| I | infection, AIDS |

| P | Psychiatric, porphyria. |

| S | space occupying lesion, stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, shock, status epilepticus |

| A | Alcohol, drugs, toxins |

| E | Endocrine, liver, lytes. |

| I | Insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, diabetes mellitus |

| O | O2, CO2, CO, opiates |

| U | Uremia, hypertension |

Drugs/poisons hypnotics, sedatives, controlled drugs, poisons (carbon monoxide, solvents), alcohol

Metabolic/ endocrine hypo and hyperglycaemia, hypothermia, hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, hepatic/renal failure

CNS pressure hydrocephalus (blocked valve), cerebral oedema

CNS injury concussion, extradural or subdural haematoma, depressed fracture

Vascular stroke, low cardiac output, cerebral or subarachnoidhaemorrhage

Epilepsy seizure, post-ictal state

Infection CNS (meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral malaria)

Generalised (septicaemia, pneumonia)

Respiratory failure carbon dioxide retention, hypoxia

Headache SAH

Distinguishing Migraine From SAH @ Medscape

Epilepsy and status epilepticus

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF TONIC-CLONIC SEIZURES IN ADULTS

The acute management of tonic-clonic seizures depends on their frequency, duration, timing and underlying cause.

General management

During the attack, take measures to avoid the patient being injured (eg protect them from hot radiators, hot water, stairs, sharp objects etc)

After the convulsive movements have subsided, put the patient in the recovery position and check that the airway is not obstructed and that there are no injuries

When the patient has fully recovered, reassure them and any attendant family/carers

Patients in whom the seizure is associated with acute or chronic alcohol excess may need to be referred for general management (for example, to treat hypoglycaemia or infection)

If the patient is a pregnant woman, she should be transferred to hospital immediately

The single seizure

Individual episodes usually stop spontaneously within 3 minutes, although in some patients the pattern is different and they can last longer. Recovery from such individual episodes is not speeded by emergency drug treatment and their management should be as outlined above.

Referral advice

If the patient has a diagnosis of epilepsy and is otherwise well controlled, early referral is usually not necessary and they should be reviewed at their next appointment with the neurologist or epilepsy nurse. The appointment may need to be brought forward if the fit might affect the patient’s employment or driving status.

If this is a first attack, the patient should be referred to be seen by a specialist within 2 weeks (??). This is to ensure early diagnosis and initiation of therapy according to their needs.

Prolonged or serial Seizures

A patient presenting with a ‘prolonged’ seizure (ie tonic-clonic movement) lasting 5 minutes or more or, with serial seizures (3 or more in an hour), should be managed as set out in the general management advice above. In addition, give rectal diazepam 10-20mg and repeat the dose after 15 minutes if necessary; buccal midazolam is an alternative, although it is currently unlicensed for this indication.

Referral Advice

Patients should be referred to hospital immediately if the seizure develops into status epilepticus (for management see section below).

Patients should be referred to hospital urgently if:

– from their previous history, there is a high risk of recurrence

– this is the first episode

– there are difficulties in monitoring the individual’s condition

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as either a run of discreet seizures without full recovery in between fits, or continuous seizures lasting for 30 minutes. The mortality and morbidity of generalised tonic/clonic status is high, and it is important to control the fits as soon as possible. The following measures should be instituted as soon as status has been diagnosed.

Management

Protect the patient from injury. Do not leave the patient alone whilst fitting or recovering; do not restrain the patient or put anything, including an oral airway, in the mouth during a seizure.

Arrange for an ambulance to transfer the patient to hospital immediately

Assess cardiorespiratory function record blood pressure and pulse rate and, if possible, and not contraindicated, give oxygen.

Measure blood glucose and if the patient is hypoglycaemic give 1mg glucagon IM or IV glucose.

Try to discover evidence of previous epilepsy and/or whether the patient is on any anti-epileptic drugs. Also try to establish the time of onset of the episode. Record this information and send it with the patient to hospital.

Drug treatment

While waiting for the ambulance give diazepam 10-20mg rectally (use rectal solution; absorption from suppositories is too slow) and repeat the dose after 15 minutes if status continues to threaten. Buccal midazolam is an alternative.

If seizures continue, and you carry it, consider giving IV lorazepam 0.1mg/kg into a large vein (usually 4mg bolus, repeated once after 10-20 minutes) or IV diazepam (as Diazemuls) 10mg over 2-5 minutes.

Coma Delirium Acute Confusional State

Any patient who is comatose (GCS less than 8) should be transferred to hospital immediately.

While awaiting transfer assess the need for basic resuscitation – ABC.

1. Maintain the airway.

2. If there is no evidence of major injury, turn the patient into the recovery position and keep them warm.

3. Give oxygen at the highest concentration possible via a facemask unless the patient has COPD.

4. If hypothermia is suspected check by measuring the core temperature.

5. Establish IV access.

6. Check for hypoglycaemia (blood glucose less than 4.0mmol/L) and if present give either glucagon or glucose

7. If an opiate overdose is suspected give naloxone IV ((DOSE))

8. If possible start treating any underlying conditions (eg meningococcal septicaemia).

Try to establish a diagnosis. Look for clues such as tablet containers, suicide notes, signs of trauma etc. Whilst examining the patient question those present about:

the onset of the coma

any previous medical or drug history

any injury or relevant social circumstances.

Management of refractory status epilepticus in adults NELM

Acute severe asthma Adults

Management depends on the age of the patient and whether the episode is moderate, severe or life-threatening.

Until the level has been defined, treat the attack as if it were severe.

Use objective measures of severity whenever possible, and record in patient’s notes. If the patient has signs and symptoms across all categories, treat them according to their most severe feature(s).

threshold for referral should be lowered if:

- the attack occurs in the late afternoon or at night

- the patient has had previous nocturnal symptoms or hospital admission

- the patient has had a previous severe attack

- there is concern over social circumstances, or the ability of patient or carer to cope at home

- If you are referring the patient to hospital, then stay with them until ambulance arrives; remember to send written assessment details with them.

| Acute Severe Asthma | Adult | Child |

|---|---|---|

| too breathless to talk | yes | yes |

| Tachynpoea | >25 | >50 |

| Tachycardia | >110 | >140 |

| PEFR | < 50% best/predicted | not usually available |

| Satts | <95% | <95% |

| Moderate | Severe | Life-threatening | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEF | >50% | 33-50% | <33% |

| Speech | Normal | cant complete sentences | Silent chest, cyanosis poor respiratory effort |

| Pulse | <110 bpm | >110 bpm | Bradycardia, dysrhythmia, or hypotension |

| Respiratory rate | <25/min | >25/min | Exhaustion, confusion, or coma |

| SpO2 | <92% | x |

Beta agonist nebulised or via spacer (1 puff x 10-20)

salbutamol 5mg or terbutaline 10mg

PLUS nebulised ipratropium 500micrograms

Prednisolone 40- 50mg if PEF>50-75% predicted/best and continue or step up usual treatment

Oxygen – oxygen 40-60%

Refer Immediately

features of acute severe asthma present after initial treatment or if the patient has had previous near-fatal asthma

Disposal

If good response to first nebulised treatment (symptoms improved, respiration and pulse settling and PEF >50%) continue or step up usual treatment and, if started, continue prednisolone for at least 5 days

Make clear arrangements to review the patient within 48 hours of an acute attack.

Remember: recovery from an acute attack of asthma is often gradual, and during the recovery phase patients are at risk of relapse and should be monitored carefully to check the patients inhaler technique

to provide a written self-management plan (including a ‘rescue’ plan) together with clear information about the indications for urgent recall

to address potentially preventable contributors to admission. Reference graph showing normal peak expiratory flow rates

Pneumothorax

DVT VTE PE Wells

- SGN 122 Dec 10 QRG

- NICE CG92 Jan 10 VTE in hospital

- EEP INFOPOEMS AUG 2011 Wells?Geneva Equally effective for ruling out PE when combined with DDimer

- qthrombosis.org/

- Wells Criteria DVT MDCalc

- Wells Score for PE MDCalc

- http://emedsa.org.au/EDHandbook/medicine/Respiratory/PE/PEScores.htm

- Management of deep vein thrombosis and prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome BMJ Oct 2011

- Pulmonary embolus BMJ 2010;340:c1421

| Wells Score for suspected DVT in calf pain | |

|---|---|

| Lower limb trauma or surgery or immobilisation in a plaster cast | +1 |

| Bedridden for more than three days or surgery within the last four weeks | +1 |

| Tenderness along deep venous system | +1 |

| Entire limb swollen | +1 |

| Calf more than 3cm bigger circumference,10cm below tibial tuberosity | +1 |

| Pitting oedema | +1 |

| Dilated collateral superficial veins (non-varicose) | +1 |

| Malignancy (including treatment up to six months previously) | +1 |

| Alternative diagnosis as more likely than DVT | -2 |

| CLINICAL PROBABILITY OF DVT | |

| >3 | high |

| 1-2 | moderate |

| <1 | low |

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I0yJTkW9y9s

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7xR0hyC-TE

DVT is a common easily missed but potentially life threatening condition. It may arise spontaneously or as a result of trauma, surgery, immobility or other risk factors. Classical clinical signs may be absent or the picture may be complicated by coexisting thrombophlebitis or cellulitis.

Wells scoring system may aid referral decisions. DDimer Blood tests may help confirm clinical impression when the index of suspicion is high but cannot itself be used for diagnosis or as a screening test. The definitive test is ultrasound and all patients with suspected or possible DVT need referral.

Background Information

Thrombosis arises in the deep veins of the lower leg as a result of

– vascular injury (fractures, surgery, burns, childbirth, infections, and venipuncture – IV Drug users ),

– immobility and stasis (pregnancy, obesity, chronic heart disease, major surgery, cerebrovascular accidents, and advanced age, air travel ) particularly in presence of risk factors promoting hypercoaguability (pregnancy, smoking systemic disease, contraceptive pill, dehydration, major surgery). Pain may precede oedema and visible swelling.

Classically the affected leg may be swollen red warm tight shiny high index of clinical suspicion is necessary for the diagnosis of DVT because many patients with a DVT are symptomatic, however classical signs include calf muscle or groin tenderness, pain, edema and sensation of warmth in the affected leg.

Investigations

Duplex Doppler ultrasound

DDImer

Treatments

Anticoagulants – heparin/warfarin (INR 2-3) /Thrombolytic /Analgesics /Antiembolism stockings (after acute episode)

Discharge and Follow Up Considerations

Refer All patients with suspected or possible DVT

Educate patient in identification of and measures to prevent venostasis particularly wrt air travel

Instruct on the importance of bed rest and elevation of the affected leg with proper placement of pillows so they support the entire length of the affected extremity to prevent compression of popliteal space

Instruct on signs and symptoms of bleeding if prescribed Warfarin

Instruct on proper application and use of antiembolism stockings and to report circulatory compromise

Q thrombosis prospective risk calculator BMJ Aug 2011

MeReC Aug 2011 – 3 month treatment for simple DVT

Acute LVF Pulmonary Oedema

Clinical features

Patients with acute left ventricular failure usually complain of sudden onset of rapidly increasing breathlessness; occasionally this is accompanied by wheezing.

The patient is usually sweating, breathless and anxious, and on examination has basal crepitations, a raised jugular venous pressure and a third heart sound.

Referral advice

Arrange for the patient to be transferred to hospital immediately.

While waiting for the ambulance, sit the patient up, establish venous access and start drug treatment. Treatment of the underlying cause can wait.

Immediate management includes:

high concentration oxygen (unless you suspect COPD)

diamorphine 5mg IV1 (2.5mg for elderly or frail patients) at a rate of 1mg/min

metoclopramide 10mg IV2. Give slowly over 1-2 minutes

sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (spray or tablet)

furosemide (frusemide) 40-80mg IV

repeat doses of furosemide and diamorphine if there is no improvement after 20 minutes.

If diamorphine causes respiratory depression give 0.4-2mg of naloxone IV every 2-3 minutes to a maximum of 10mg.

If an oculogyric crisis occurs give 5-10mg of procyclidine IM and repeat after 20 minutes if necessary.

Pneumonia (emergencies – adults)

hacking-medschool/pneumonia-respiratory

hacking-medschool/community-acquired-pneumonia-cap

| Pneumonia = cough + LRTI symptom(s) + (new) focal sign(s) + systemic symptoms |

Clinical features

fever, pleuritic pain and dry cough. Other characteristic features include shortness of breath, productive cough and haemoptysis as well as non-specific features such as headache, rigors, confusion and delirium.

Common signs of pneumonia are tachycardia, tachypnoea, focal crepitations and, rarely, bronchial breathing. A pleural rub may be heard or there may be evidence of a pleural effusion.

Elderly patients may present non-specifically with features such as confusion, and only careful examination of the chest reveals the likely diagnosis of pneumonia.

Management in the community

Patients with uncomplicated pneumonia can often be managed in the community, but for some, pneumonia is life threatening. Those at particular risk are the very young, the very old and those with underlying diseases such as chronic cardiorespiratory disease or diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include alcoholism and immunosuppression (as in patients with organ transplants or AIDS). Pneumonia can also follow bronchial obstruction caused by cancer or by the inhalation of a foreign body.

Start with amoxicillin (500mg-1g tds) or erythromycin (500mg qds)/clarithromycin (500mg bd) up to 10d

Patients should be reassessed within 48 hours and if they have not responded to treatment either:

– arrange a chest X-ray to confirm the diagnosis

– add erythromycin or a tetracycline to cover Mycoplasma infection (rare in the over 65s)

– refer to hospital

Patients should be transferred urgently to hospital if they have a ‘CRB-65’ score of 3 or 4. If the patient is severely ill and not allergic to penicillin give a stat dose of benzylpenicillin (adult dose 1.2g IV) prior to transfer.

The threshold for referral should be lowered in patients with:

coexisting chronic disease

psychosocial reasons why they cannot manage at home

an oxygen saturation less than 92%.

Patients should be referred to see a specialist within 2 weeks if you suspect there may be an underlying malignancy.

Patients should be referred for diagnosis of HIV status if you suspect HIV/AIDS is a possible underlying cause.

| Causative organisms |

|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| respiratory viruses |

| Haemophilus influenzae |

| Legionella pneumophila |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae |

Death results from CAP in around 1% of cases rising to over 10% in the elderly and those with chronic heart failure renal failure liver failure a deficient immune system or cancer. (CAP patients who require hospital admission sustain over 20% mortality.) This risk of death is reduced by prompt diagnosis and treatment.

CAP vs HAP

CAP is pneumonia that begins to develop outside hospital in patients who have not been inpatients. The invading organisms are often found among the normal flora of the human upper respiratory tract. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) occurs after admission to hospital for some other serious condition. It is caused by a variety of often antibiotic-resistant bacteria from a number of sources, most commonly intensive-care units (ICUs) in patients who are being mechanically ventilated.

Nursing-home-acquired pneumonia

Apart from the fact that patients in nursing homes are often frail and elderly, there is some evidence that when they develop pneumonia, the causative bacteria are generally similar to those that cause CAP. Consequently, similar treatment regimens should be used. Due to their age they are more likely to require hospital admission

All children suspected of having pneumonia must be admitted without delay to a specialized paediatric intensive-care unit.

Treatment of CAP General measures

A sputum sample and two pre-antibiotic blood cultures should be taken for bacteriology. Do not delay specific treatment by waiting for results

2 A full blood count and serum electrolytes and urea should be sent for urgent analysis.

3 A pulse oximeter should be used to estimate the patient’s haemoglobin oxygen saturation. Supplementary oxygen should be available from a concentrator, via nasal ‘spectacles.’

4 Near-patient screening for the causative organisms should soon be generally available, based on the presence of urinary antigens to specific organisms pneumococcus and Legionella.

5 The patient must stop smoking, stay in bed and drink copious fluids.

6 Analgesia is important if the patient develops pleurisy, e.g. strong co-codamol tablets (30/500) in the dose needed to relieve the pain. Stronger opioids (morphine-like drugs) are not recommended, since they all depress the respiratory control mechanisms.

Pneumonia is prone to cause complications in 5-20% of patients – pleural effusion or empyema pus, cardiac failure, endocarditis, meningitis, organ failure. Patients should be reviewed twice daily whether at home or in a nursing home, and admit to hospital if there is either deterioration or an inadequate response to treatment.

Abdo pain adult

http://hacking-medschool.com/abdo-pain-adults/

GI bleed |

|

|---|---|

| Haematemesis | Vomitting blood – fresh or altered |

| Malaena | Black tarry stools – due to bacterial breakdown of Hb – at least 100mls must be present |

| Haematochezia | Bright red fresh blood PR |

| SIGN qrg 105 GI bleed Sep 08 (pdf)Rockall GI Bleed Score | |

Acute upper GIB may present with haematemesis, melaena, or symptoms of hypovolaemia or anaemia. These features can occur as the result of a sudden large bleed or continuous slow bleeding over many days. Mortality increases with the age of the patient, the ammount and briskness of the bleeding and the coexistence of other medical problems.

Patients should be transferred to hospital urgently in any of the following situations:

- frank haematemesis or unformed melaena stool in the previous 24 hours (evidence from history or rectal examination)

- hypotension or tachycardia

- history of syncope even if now recovered

- liver disease or varices

- anticoagulants or coagulopathy.

Patients managed at home should be referred for endoscopy which should be undertaken within 2-3 days (??).

Endoscopy will help guide management and this may be particularly useful for patients needing aspirin or NSAIDs in the future. If outpatient endoscopy within 72 hours is unlikely, it may be better to arrange for the patient to be admitted.

- The threshold for referral should be lowered if the patient:

has anaemia

has co-morbidity (eg ischaemic heart disease, renal impairment)

is aged over 60 years

has had a previous gastric ulcer

cannot be supported or supervised at home.

If there is any evidence of further bleeding while awaiting endoscopy then the patient should be transferred urgently (???) to hospital. Ensure that patients have the information needed to allow them to deal with this eventuality if it occurs.

Gastroenteritis / food poisoning

Presents as acute diarrhoea (3 or more unformed stools per day) plus:

abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever, bloody stools and faecal urgency.

Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously over 1-2 days and antimicrobial therapy is rarely necessary.

Food poisoning, whether suspected or confirmed, is a notifiable disease even if the organism is not known.

Management

For patients with typical acute food poisoning:

examine the abdomen to exclude intra-abdominal pathology

advise the patient about fluid and electrolyte replacement; approximately 2 litres of oral rehydration solution such as Dioralyte or Rehidrat should be

taken in the first 24 hours and 200mL per loose stool thereafter

anti-emetics may help if the patient is vomiting severely

antimotility drugs such as codeine phosphate and loperamide hydrochloride may make symptoms easier to cope with.

If the patient is a food handler or a health-care worker, notify the Consultant in Communicable Disease Control (CCDC). Advise such patients not to work until they have been reviewed by occupational health or public health. If you suspect an outbreak of gastroenteritis or need advice on control contact the CCDC.

Stool microscopy/culture is necessary when:

the patient is febrile

stools contain blood

the patient has recently returned from a country where infections are likely

the patient is taking, or has recently taken, a broad spectrum antibiotic (request Clostridium difficile toxin detection)

the patient is a food handler whose occupation is such that they might spread the condition.

Referral advice

Patients should be transferred to hospital urgently (???) if they:

are severely dehydrated

have bloody diarrhoea

have severe constitutional upset.

If the patient is dehydrated start an intravenous infusion of sodium chloride 0.9% while awaiting transfer. Others may need to be referred depending on the results of stool microscopy.

The threshold for referral should be lowered if the patient is at increased risk from complications of infection; for example, older people, the immunocompromised, patients with renal failure or inflammatory bowel disease. Those taking immunosuppressants or systemic corticosteroids are also at increased risk.

Bacterial Gastroenteritis in Adults

Organisms: Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella spp

Less common: E.coli 0157, Shigella. spp (for both usually history of bloody diarrhoea)

Management

Send sample in all cases of bloody diarrhoea, protacted symptoms or infection following travel, outbreadks in community settings, those with co-morbid factors

Oral rehydration therapy

If bloody diarrhoea, dysenteric symptoms (i.e. bloody diarrhoea with abdominal pain/tenderness and fever), high risk cases with hypo-chlorhydria, IBD, immunosuppressed or protracted diarrhoea refer or discuss with Infectious Diseases Specialist. Always consider haemolytic uraemic syndrome in patient with “bloody diarrhoea”

Avoid anti-motility drugs or opiates

Antibiotic not usually indicated

Use of antibiotics in E.coli 0157 may precipitate haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Diarrhoea in Returning Traveller

Organisms: Consider above but also giardiasis, amoebiasis or cryptosporidiosis.

Management

Stool for microscopy & culture. Discuss with microbiology laboratory

Oral rehydration therapy

Discuss with Infectious Diseases Specialist, especially if there is blood in stool, for advice on empiric ciprofloxacin 500mg twice daily or metronidazole 800mg three times daily for 5 days.

Diabetic emergencies

DKA

HONK

| Hypoglycaemia DKA HONK | Hypoglycaemia | DKA | HONK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Symptoms | rapid (mins-hrs) | slow (hours to days) | Slower (hours to days) |

| BP | normal or raised | lower | lower |

| Breath Odour | normal | fruity acetone pear drops | normal |

| GI | none | anorexia nausea vomitting diarrhoea abdo pain and tenderness | none |

| Muscle strength | normal or reduced | weak | weak |

| Neurological State Early | irritability nervousness giddiness tremors difficulty speakking concentrating focussing coordination paraesthesia | dullness confusion lethargy decreased reflexex | dullness confusion lethargy decreased reflexex |

| Neurological State Late | hyperreflexia dilated pupils coma | coma | coma |

| Pulse | tacycardia – till late stage coma then bradycardia | mild tachycardia weak | usually rapic |

| Resps Early | normal to rapid | deep fast | normal |

| Late | slow | Kussmuals | Rapid |

| Skin & mucous membranes | Cold clammy skin pallor sweating norma mucous membranes | warm flusherd dry loose skin crusty mm soft eyeballs | warm flushed dry extremely loose skin dry crusty lips soft eyeballs |

| Temp | often decreases, may be raised after episode | hypothermiapossible fever from dehydration or infection | hypothermiapossible fever from dehydration or infection |

| Weight | stable | decreased | decreased |

| Other | hunger | thirst | initial thirst – later may be absent(NFIQ 2007 Lippincott) |

| ABGs | normal or slight resp acidosis | metabolic acidosis with compensatory alkalosis | normal or slight metabolic acidosis |

| Blood Glucose | low | high | very high |

| HCT | normal | raised | raised |

| Serum Ketones | negative | Positive +++ | negative or + |

| Serum Osmolarity | normal (<310 mosmol/l) | raised (310-330 mosmol/l) | markedly raised (350- 450 mosmol/l) |

| Serum K | normal | normal or high | normal or high |

| Serum Na | normal | normal or low | normal high or low |

| Urine glucose | normal | high | very high |

| Urine Output | normal | initial polyurialate oliguria | initial marked polyuria |

| Treatment | glucose glucagon | insulin fluid replacement electrolytes (bicarb?) | fluid insulin electrolytes |

Lactic Acidosis

Rarely, metformin may cause lactic acidosis, especially in patients with renal impairment or with conditions that cause poor tissue perfusion such as cardiac failure, hypoxia, sepsis, hepatic impairment or dehydration. The most obvious clinical feature is hyperventilation. If lactic acidosis is suspected the patient should be transferred to hospital immediately.

Diabetes illness rules

hacking-medschool/diabetes-illness-rules-2

Hypogycaemia

HYPOGLYCAEMIA (blood glucose below around 4.0mmol/L)

In patients on insulin, hypoglycaemic symptoms usually develop rapidly; in those on an oral hypoglycaemic, onset is often insidious and may even be intermittent, sometimes presenting as a personality change, focal neurological signs, hunger or dizzy spells. Remember that some patients without diabetes may take insulin or other hypoglycaemic drugs as a form of self-abuse. Severe illness in children may also cause hypoglycaemia.

Clinical features

Features of hypoglycaemia may include sweating, tachycardia, tremor, visual disturbance, focal neurological signs, changes in mental state (confusion, uncooperative behaviour), headache, convulsions, and ultimately coma and death.

Initial management

Blood glucose concentrations at which symptoms develop vary. In principle, anyone with a level below around 4.0mmol/L should be considered at risk. If possible, check blood glucose by finger, or ear lobe, prick test (remember to wash and dry the prick site before taking the blood). If you are unable to measure blood glucose but you suspect severe hypoglycaemia then give glucose anyway it won’t harm the patient. If hypoglycaemia is confirmed or suspected, treatment depends on whether or not the patient is co-operative.

Oral glucose For mild to moderate hypoglycaemia where the patient is conscious and cooperative give 10-20g of a rapidly absorbed carbohydrate.

This should raise blood glucose levels within 5-15 minutes. Give more glucose after 10-15 minutes if necessary.

Approx 10g of glucose is available from: Sugar 2 teaspoons or 3 sugar lumps Hypostop gel Glucose 9.2g/23g oral ampoule

Milk 200 mL Lucozade/sparkling glucose drinks 50-55mL Coca-Cola 90mL Ribena original 15mL (dilute with water)

As symptoms improve or normoglycaemia is restored, additional long-acting carbohydrate should be given orally to maintain blood glucose levels unless a snack or meal is imminent.

Parenteral glucose For severe hypoglycaemia, where the patient is unable to take food or fluids orally and is semi-conscious or comatose, give IM glucagon, which takes around 10 minutes to work.

under 8 years old (body weight less than 25kg) 500microgra ms

over 8 years old (body weight more than 25kg) 1mg Glucagon

Adult 1mg IM, IV or SC

If the patient has not responded within 10 minutes of giving glucagon, call an ambulance (????) and, if you carry it, consider giving IV glucose.

Glucose must be given IV. Recovery usually occurs within 5 minutes of injection. Repeat the dose after 5 minutes if there is no response. High

concentration glucose is very irritant (especially if extravasation occurs) and should be given into a large vein through a large-gauge needle. If possible,

flush with sodium chloride 0.9% after administration.

Strength Dose Route

Child 10%1 2-5mL/kg IV

20% 50mL IV

Glucose

Adult 50% 25mL IV

1To make 50mL of 10% glucose Using a 50mL syringe with a large bore

needle draw up 10mL of 50% glucose and make it up to 50mL with water for

injection, then mix before injecting into a large vein.

If there is no recovery, or there are residual symptoms despite raising blood

glucose to normal, the patient should be transferred to hospital immediately

Referral advice

Patients with hypoglycaemia should be transferred to hospital immediately if:

they do not respond to glucagon/glucose

there is residual neurological deficit.

The threshold for referral should be lowered if the patient:

is unable to manage alone

raises additional clinical concerns

is a child or elderly

is taking an oral hypoglycaemic (as the effects may persist for many hours).

Subsequent management

As soon as feasible start oral glucose and complex long-acting carbohydrates and monitor blood glucose levels. If a long-acting hypoglycaemic agent has been taken, hypoglycaemia may recur. To avoid a subsequent ‘hypo’ the patient should continue having a high carbohydrate intake for 24 hours.

Blood glucose control following hypoglycaemia may be poor for a few days.

Advise the patient/carer to discuss the episode with their diabetes team. The GP, or diabetes clinic responsible for the long-term management of the patient, should try to establish why hypoglycaemia occurred in order to develop strategies to prevent it happening again. Hypoglycaemia can often be anticipated or promptly reversed by good patient/carer education.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis DKA

Blood glucose usually > 25

patients with type 1 diabetes

often precipitated by minor illnesses eg UTI ,GE or URTI.

Rate of development of ketoacidosis varies. If it is the presenting feature in a new patient with diabetes it may have taken days to become established. In an otherwise well-controlled patient with diabetes, some symptoms may begin within a few hours of glucose levels rising.

Clinical Features

polydipsia and polyuria, malaise and weakness, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, confusion, disturbance of consciousness and ultimately coma and death. Initially the symptoms may be masked by those of the precipitating illness. Typical findings on physical examination include:

tachycardia, postural hypotension, evidence of dehydration, fast, laboured breathing (Kussmaul breathing), and a smell of acetone on the breath

Diagnosis

clinical history

physical examination

the presence of glucose and ketones in the urine

a high blood glucose level from finger or ear lobe prick test.

Referral / Disposal

Transferred to hospital immediately . If transfer is delayed it may be appropriate to start IV fluid replacement (eg with sodium chloride 0.9%) and to give insulin, but this should only be done after discussion with the hospital medical or paediatric team.

- DKA PANICS

Potassium

Aspirate stomacch / ng tube

Normal saline

Insulin infusion

Cultures Catheterise MSU blood cultures

Subcut heparin

HONK

Hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma.

Characterised by profound dehydration, hyperglycaemia and coma with absent or low ketones. High Mortality

Elderly (or middle aged) patients with NIDDM often precipitated by have an underlying illness such as infection, myocardial

infarction. The clinical features may develop over days or weeks and may be the first presentation of diabetes. Ultimately, the patient may present with focal neurological signs, seizures or coma. The risk of coma is increased in patients taking drugs such as phenytoin, propranolol, cimetidine, thiazide or loop diuretics, corticosteroids or chlorpromazine.

Patients should be transferred to hospital immediately for rehydration, correction of a grossly disordered metabolic state and treatment of any precipitating cause. If transfer is delayed it may be appropriate to start IV fluid replacement (eg with sodium chloride 0.9%) and to give insulin, but this should only be done after discussion with the hospital medical or paediatric team. Don’t delay treatment of a life-threatening precipitating cause if it can be identified.

Ischaemic limb

Early detection and treatment of acute limb ischaemia NPSA

http://hacking-medschool.com/arterial-thrombus/

Cauda equina syndrome

http://caudaequinasyndrome.co.uk/medicalprofessionals.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zl_EkRD6J28&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1VN5-R3PSU

Sickle cell crisis

Sickle cell disease covers a group of disorders which include sickle cell anaemia (homozygous haemoglobin SS), sickle cell haemoglobin C disease and sickle cell beta thalassaemia.

The responsible genes most commonly occur in people of African/Caribbean, African, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern or Asian origin.

All patients with sickle cell disease will have chronic haemolytic anaemia and intermittent pain crises and are at risk of organ damage. In the majority of episodes, pain is the predominant symptom (pain crisis), but there are other types of episodes which may be life threatening and are vital to recognise.

Presenting features

pyrexia

anaemia (eg sequestration)

dyspnoea and pain (eg acute chest syndrome)

abdominal pain (eg mesenteric syndrome)

confusion (eg cerebral sickling)

paralysis (eg stroke)

loss of vision (eg hyphema, retinal detachment)

fitting

prolonged painful erection (priapism).

pyrexia

Sickle cell disease should be considered in any patient from any of the susceptible groups presenting with signs and symptoms compatible with a crisis. Most patients will have had previous crises and will recognise the symptoms. The patient’s own assessment is usually a good indication of severity. If a crisis develops, most patients will be helped by the administration of fluids and oxygen.