56

- Wheeless’ Textbook of Orthopaedics online

- American academy of orthopaedic surgeons aaos.org

- Orthopaedics Tulane University

- Shoulderdoc.co.uk

- world ortho.com

- orthopaedic weblinks.com

- Orthopaedics medmatrix.org

- Orthogate.org

- Orthopaedics Rural Health West au

- Sports Injuries Rural Health West au

MSK regional conditions

http://130.60.57.53/anatomy/Anatomy.html

Spinal anatomy

Cervical spine examination

- Cervical spine examination Rehabmanual.com

- Cervical spine examination Orthofracs.com

- youtu.be/vHQHrjMlOEU

- youtu.be/e3QXEjnxgyw

- youtu.be/YwR9EcKN_Jc

Thoracic spine examination

Lumbar spine examination

- Anatomy and Examination – UCSD

- Back Exam Patient UK

- youtu.be/jJIJ2sHVOoM

- youtu.be/bfrgN64ojRY

- youtu.be/ljzzYPeXOFk

- youtu.be/O49dwZ2CW5A

- youtu.be/a_ptmvfOe9c

Neck pain

Neck pain and sprains are common. Presentations include acute torticollis whiplash esp RTA, and degenerative disease in the middle aged and elderly. Whiplash can take up to 18m to settle but a positive approach from outset with rehabilitation advice can help reduce this.

Key Points

Accurate mechanism of injury

Follow Ottowa rules for management including Xray in acute Cspine injury. Refer immediately for neurological signs.

Beware central cord syndrome in elderly patient recieving blow to face

Examination

Undress patient to underwear to fully expose back

Inspect

symmetry swelling bruising muscle spasm asymmetry of posture

Feel/palpate

spinal processes for warmth & tenderness

percuss spinal processess with heel of hand

Test the following movements:

• Flexion (looking down at toes)

• Extension (looking up at ceiling)

• Lateral flexion (putting each ear onto the shoulder in tum)

• Lateral rotation (looking over each shoulder in tum).

Fix the shoulders when assessing flexion, to ensure that movement is occurring at the cervical spine rather than the shoulders.

Normal findings/ROM

(included to give an idea only while its difficult to be precise it is useful and more satisfying to be able to document findings objectively)

Flexion 50 degrees

Extension 75 degrees

Lateral Flexion 45 degrees

Rotation 70 degrees

Common conditions

Whiplash

Acute Torticollis ( young adults children, ?due to minor disc protusion – lasts few days (5-10)

OA

Investigations

C spine XRay for traumatic injuries (and immobilisation if) High velocity, age >65, paraesthesia in extremeties, immediate onset of pain, not moved since injury (not likely in WIC) midline Cspinne tendernes, inability to rotate neck to 45 degrees L+R, associated head injury

Acute neck sprain

Whiplash injury

Cervical spondylosis

- Cervical Spondylitis PUK

- Cervical radiculopathy BMJ 2009

- Cervical Sponylosis Medscape

- youtu.be/-9s28eQJcUE

- youtu.be/zUm6k1LJdk0

Cervical Disc

Cervical spine xrays

Thoracic spine pain

- Thoracic spine pain MD Gudelines

- Thoracic pain Richard Walker Pain Clinic

- Thoracic discogenic pain syndrome Medscape

- Thoracic disc injuries Medscape

- youtu.be/jxOUWyItTzw

- youtu.be/0OPL87ih7B4

- youtu.be/Tk8L2aF2cn4

Low back pain

Diagnosis

1. Is it mechanical backache or is there some underlying pathology?

(i) The older patient with possibilities of osteoarthrosis, osteoporosis, Paget’s disease and malignant deposits in the spine. In the elderly an Xray may be worthwhile

(ii) The young patient with low back pain and morning stiffness who may have ankylosing spondylitis

(iii) Referred pain – renal or gynaecological

(iv) Infection

(v) Depression can present as backache

Mechanical backache is likely to be episodic, related to posture, worse on movement and relieved by rest.

Back pain without these features, in the young « 20 years), in the elderly, that is progressive or continuous, or associated with systemic symptoms demands fuller investigation

2. If the pain is mechanical is it due to a prolapsed intervertebral disc? Practically this means, are there symptoms of nerve root compression?

Examination

Observe the curvature, feel where the tenderness is and test movement

Important part is the testing of straight leg raising (SLR) and the femoral stretch test (knee flexion when prone), the latter to detect higher (L 3/4) root pressure

A motor and sensory examination together with testing the reflexes is not likely to be a feature of the examination unless a disc prolapse is suspected

Much can be learnt from patient’s demeanour and posture and by simple enquiry (? sciatica, ? recent injury, ? occupation, etc.)

The rare central disc prolapse presents with urinary symptoms and severe weakness of the legs peripherally and requires an immediate referral for emergency surgery Red Flags in Low Back Pain Red flags such as bilateral or alternating leg symptoms, neurological disturbance, sphincter disturbance and history of malignancy help to identify those who need investigation.

Acute back pain is an exceedingly common complaint that affects up to 75% of all adults during their lifetime. Most causes are benign and recover within 2-3 weeks but serious etiologies must be considered. Patients with back pain typically experience difficulties with work and performing activities of daily living.

Red Flags

- Signs or symptoms of Cauda equine syndrome – Saddle anaesthesia, faecal incontinence poor anal tone pn PR – needs immediate referral to prevent permanaent disability

- Unexplained weight loss

- Unexplained fever

- Guarded movement

- Inability to bear weight or walk

- Night time pain or pain worse when recumbent

- Significant trauma

- Persistance

- Middle age and older

- AAA

Bowel or Bladder problems, bilateral lower limb paraesthesia or weakness, saddle anaesthesia in cauda equina syndrome

Age <20 >55

Thoracic Pain

Steroids

Weight Loss

H/O Cancer

AAA in elderly

Consider Vertebral Crush Fracture in osteoporotic elderly.

Physical exam for focal neurologic deficits

Analgesics

Rest until cause determined and pain controlled

Emergency transfer to facility with MRI and neurosurgical capabilities

Most causes of acute back pain are benign musculoskeletal or mechanical disorders but the clinician should be aware of more serious neurological, vascular and visceral causes.

Mechanical Back Pain

Acute strain or sprain of the back is often diagnosed by history alone. There is typically a preceding injury involving the lifting or moving of heavy objects. There may be no specific findings on physical exam, other than mild soft tissue tenderness.

Age related changes to the bony structure of the spine and discs lead to localized pain – especially common in the lumbar spine.

Compression fractures are often traumatic in nature and can be elicited on exam by midline tenderness. Atraumatic fractures may occur in the elderly.

Radiation of pain to the lateral or posterior leg is consistent with disc herniation and sciatica. Bilateral lower extremity pain is more likely the result of overall narrowing of the spinal canal known as spinal stenosis.

Muscle spasm of either upper or lower back musculature can readily be palpated during physical exam.

Non-mechanical Spinal Pain

Much less common causes of spinal pain include bony tumors, often from metastatic disease. These lesions typically cause unremitting, focal pain in the midline. Infections including spinal epidural abscess may cause more generalized pain and constitutional symptoms such as fever.

Intra-abdominal/Intra-thoracic Related Back Pain

A thorough exam of the heart, lungs, abdomen and bilateral pulses accompanied by a complete history is necessary if these diagnoses are a consideration.

Upper back pain may be attributed to radiation of pain from the thorax including thoracic aortic aneurysm, pulmonary embolus and pneumonia.

Lower back pain can be caused by abdominal aortic aneurysm, pelvic organ diseases, urinary tract infections, kidney stones and ectopic pregnancy.

Uncommonly, shingles may cause pain in a dermatomal region of the back prior to the appearance of the classic vesicular rash.

Treatments

NSAID’s or Paracetamol

Benzodiazepines or muscle relaxants

Opioid/analgesic combination – not shown to be more effective than NSAID’s but may provide short term relief.

Localized heat

Activity restriction

Patient education is important: recurrence of back pain is common. Demonstrate proper bending and lifting techniques.

Physical therapy

Massage; acupuncture; spinal manipulation

Return to work/activity as tolerated. No bed rest recommended.

Neurosurgery referral

Red flags in low back pain

Fracture

Major trauma (motor vehicle accident, fall from height)

Minor trauma or strenuous lifting in an older or osteoporotic patient

Tumor or infection

Age >50 years or <20 years

History of cancer

Constitutional symptoms (fever, chills, unexplained weight loss)

Recent bacterial infection

Intravenous drug use

Immunosuppression (corticosteroid use, transplant recipient, HIV infection)

Pain worse at night or in the supine position

Cauda equina syndrome

Saddle anesthesia

Recent onset of bladder dysfunction

Severe or progressive neurologic deficit in lower extremity

Diagnosis and management

Red Flags are symptoms and conditions that require urgent imaging, blood tests and referral. They include the following.

A past medical history of carcinoma, TB, drug abuse and HIV (cause of immunosuppression and infection).

Previous prescription drug use (e.g. steroids).

Symptoms of night sweats, fever and loss of weight.

A new structural deformity (e.g. kyphosis) suggestive of fracture.

Widespread neurology:

cauda equina symptoms these need immediate referral as there is a risk of permanent damage and incontinence. These symptoms include:

loss of sphincter control

bilateral neurological leg pain

saddle loss of sensation.

Low back pain

Low back pain is common and patients may present with acute or chronic problems.

Most is mechanical back pain following an acute strain or prolonged unaccustomed activity.

It requires reassurance simple analgesia and advice re staying mobile.

Radiation to the buttock or leg is common though true sciatica radiates below the knee.

Even acute disc prolapse usually settles within weeks with conservative treatment.

Examination is directed to confirm clinical impression exclude serious pathology or neurological emergency

Examination

Undress patient to underwear to fully expose back

Inspect

spinal profiles when upright and bending down – note curves and symmetry when upright and bending down (kyphosis lordosis scoliosis)

Feel/palpate

spinal processes for warmth & tenderness

percuss spinal processess with heel of hand

Move (active)

Test the following movements:

• Flexion (touching toes)

• Extension (leaning backwards)

• Lateral flexion (sliding the hand down the side of the right leg and then the left)

• Lateral rotation (twisting at the waist to the left and then the right).

Fix the pelvis when assessing lateral rotation. Do this by stabilising the pelvis with your hands, or performing the examination with the patient sat on the edge of the couch.

Special tests

Straight-leg raising

(for nerve root irritation)

Active and Passive

With the patient supine, use your arm to fix the patient’s pelvis at the anterior superior iliac spines.

The patient then attempts to flex the hip as far as possible with the knee fully extended – raise your straight leg towards the ceiling

Stretch test

(for sciatic nerve root irritation)

With the limit of straight-leg raising reached, allow the leg to lower slightly, then dorsiflex the foot (push the toes towards the head) quickly. If this causes severe pain the test is positive.

Test patella and achilles reflexes for weakness of ankle dorsiflexors and extensor hallucis (L4 L5 prolapse) weakness of the peroneal muscles toe flexors calf and tibialis posterior (L5 S1 prolapse)

Test function

Ask the patient to:

• put on a coat

• take off and put on their shoes.

Examine hip and knee as necessary

Normal findings

ROM Reflexes Myotomes Dermatomes MRC scale

Flexion 60 degrees

Extension 25 degrees

Lateral flexion 25 degrees

Rotation 30 degrees

Investigations

Consider ESR/PSA in elderley

Plain Xray unhelpful except to diagnose AS in young or vertebral collapse or malignancy in the elderly

MRI if nerve root symptoms persist >4 weeks.

Mechanical Back Pain

Mechanical Back Pain

Lumbar disc prolapse

Sciatica

Piriformis syndrome

Spondylosis OA spine

- Lumbar spondylosis Medscape

- spine health.com spondylosis what it means

- spinal disorders.com lumbar spondylosis

Spinal stenosis

- youtu.be/HpE9HU0i_bE

- youtu.be/YC62lgFb_yA

- Lumbar spinal stenosis JAMA 2010

- NICE IPG 365 2010 Interspinous distraction procedures for lumbar spinal stenosis

Spondylolisthesis

Sacroiliac syndrome and sacroiliitis

- youtu.be/1iwmcCw4bAw

- youtu.be/xxktB0kqIeY

- Sacroiliac Syndrome medscape

- Merck Manual seronegative spondyloarthropathies

- Reiters Medscape

Coccydynia

Lumbar spine manipulations

examples only – not yet organised

Lumbar spine Xrays

Shoulder anatomy

Shoulder conditions

rotator cuff disorder – inc tears, tendonitis and impingement syndromes

glenohumeral disorders – inc frozen shoulder and OA

acromioclavicular joint disorders

referred neck pain

myofascial conditions

Shoulder assessment

Red flags

history of, or suspicion of, cancer

possible unreduced dislocation

trauma plus acute disabling pain plus significant weakness suggesting acute rotator cuff tear

possible neurological lesion

referred pain – cardiac pain, gallbladder diaphragm, neck

Shoulder Exam

1. Introduction

The Shoulder Girdle is a sophisticated and complex unit that allows wide range of movement of the arm and hand free from the body but sacrifices some stability and is prone to acute an chronic injury as a result.

The shoulder joint proper is the glenohumeral joint – there are also acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular scapulothoracic and subacromial joints. When examining the shoulder girdle it is important to isolate the specific joints /movements.

Shoulder pain can be referrered from the neck. Common conditions are adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) rotator cuff pathologies (eg supraspinatus tendinitis)

2. Red flags

Consider referred pain from C-spine or heart or diaphragm/abdomen. (MI, pneumonia, intra-abdominal pathology)

Anterior dislocation of shoulder usually obvious. Beware posterior dislocation in Epileptic fit/ electric shock

Suprsapinatus tear may need operative treatment in active young sportspeople – refer if unable to abduct actively.

3. Systematic Examination

Expose both knees adequately. Clarify main site of pain.

– Look

Observe the patients face and demeanor for signs of pain

Compare both sides front and back.

Observe for swelling redness bruising scars deformity

– Inspect/Look for – deformity of the clavicle or the AC joint, muscle wasting (deltoid, axillary nerve damage) asymmetry or loss of contour at the shoulder – a step in the deltoid contour or a gap below the acomium (subluxation or dislocation)

– Feel for areas of warmth (using back of hand)

swelling, crepitus, bony tenderness,

examine systematically from the

Sternoclavicular joint

along the clavicle

the acromioclavicular joint and

around the borders of the acromium

corocoid process (often tender in normal people)

head of humerus

spine and body of scapula

greater tuberosity of humerus (rotator cuff insertion & biceps tendon insertion)

Move

Active Motion

Abduction/Adduction With the elbow fully extended ask the patient to bring the arm away from the body until the fingertips point to the ceiling (abduction) and then swing the arm across the trunk (adduction)

With the elbow flexed at 90 degrees and tucked into the side ask the patient to turn the forearms outwards away from the body (external rotation) and then inwards towards the trunk (internal rotation)

Full internal rotation is blocked by the patients own torso. It can be assessed by asking the patient to see how far up between the shoulder-blades they can reach with the back of their hand behind the back.

Passive Motion

When testing passive abduction and adduction fix the scapula by grabbing the inferior angle to assess the degree of scapular rotation.

For passive internal rotation continue the movement behind the back of the patient.

Passive

test strength of active motion

abduction/adduction (0-170)

forward flexion (0-160)

backward extension( 0-60)

external rotation (put your hand on the back of your head)

internal rotation (put your hand behind your back to touch your shoulder blade

Note: crepitus on movement , restriction, pain (note painful arc – pain develops betwen 80-120 degrees then subsides)

and and weakness of particular movements test sensation over the deltoid (axillary nerve C5)

Special Tests

– Ask the patient to push against wall with flat of their palms and look for winging of the scapula (long thoracic nerve, serratus anterior)

– ask patient to abduct the shoulder against your hands with the thumbs pointing upwards (painful in supraspinatus tendinitis) (Tin Can Tests)

– ask patient to shrug the shoulder against your hands (spinal accesory nerve CN11)

– Scarf test ask patient to put hand on opposite shoulder then push against elbow (ellicits pain in AC joint pathology)

Tests for impingement

– Neers Impingement Test – fully abducting the straight arm will recreate symptoms

– Hawkings impingement test – hold arm at 90degees abduction and 90 degree elbow flexion rotation of the arm across the body will recreate symptoms

Functional Tests

Ask the patient to:

put their hands behind their head with elbows as far back as possible

scratch the centre of their back as far up as possible

put on a coat

Examine cervical spine as appropriate if shoulder examination does not reveal a cause for symptoms

Normal findings

abduction/adduction (0-170)

forward flexion (0-160)

backward extension( 0-60)

external lateral rotation ( 0-90 degrees)

internal medial rotation (0-70 degrees)

Common abnormalities and their significance

Clinical Pictures in Rotator Cuff Injuries

supraspinatus anterior deltoid abduction (painful arc)

infraspinatus posterior deltoid lateral rotation

subscapularis anterior/deltoid medial rotation /adduction

teres minor scapular lateral rotation

Common conditions

Frozen Shoulder

Rotator Cuff tears (often degenerative in middle age cf acute injury)

Impingement Syndrome

Fractured head of humerus in elderley

Shoulder exam

- hacking-medschool/shoulder-exam-2

- ucsd.edu/joints2

- youtu.be/VSrLbzZzJU8

- youtu.be/RsTObF8W9Ds

- youtu.be/WV1DJBpg2tc

- youtu.be/p60X8fADTeg

Shoulder special tests

- uwa.edu/shoulder

- usask.ca fmse

- youtu.be/rAmJccsG4uI

- youtu.be/f4hNiNGdP9A

- youtu.be/tdmRTQidaiI

- youtu.be/W0KnejfMtT0

- youtu.be/xVQy0qPU3Ho

- youtu.be/f9IoPmx-nfs

- youtu.be/Q3gIjMkg91k

- youtu.be/LPbc7HfHlAQ

- youtu.be/_8HB38Bx6WQ

Rotator cuff injury

S supraspinatus

I infraspinatus

T teres minor

S subscapularis

- Rotator Cuff Medscape

- youtu.be/Tg0eDAqaL-g

- youtu.be/i5vXk6u18dc

- youtu.be/e8NbW-dyxTY

- youtu.be/amonHbKwMec

- youtu.be/LmkEFLSpGGY

- youtu.be/xVQy0qPU3Ho

- youtu.be/WOabOI2Z4FA

- youtu.be/ZhN1_ZJyUnk

- youtu.be/uP4NYnycq4

Supraspinatus problems

Infraspinatus problems

- youtu.be/UfBLQqptUcg

- youtu.be/au-Sg0sMarw

- youtu.be/xVQy0qPU3Ho

- youtu.be/EzIZIwgCTQ4

- youtu.be/O6SL4SSBBmQ

Bicipital tendinitis

Subacromial bursitis

Acute subdeltoid bursitis – cyriax

- YT Functional examination shoulder – Cyriax orthopaedic medicine

- YT Cyriax transverse friction massage supraspinatus

- YT Cyriax transverse friction massage infraspinatus

- YT Intra-articular injection in the shoulder joint for arthritis, see www.cyriax.eu

- YT Mill’s manipulation, tennis elbow ; www.cyriax.eu

- YT Injection CTS

- YT Spinal lumbar stretch manipulation, www.cyriax.eu

- YTSpinal lumbar leg over manipulation, www.cyriax.eu

- YT Cyriax orthopaedic medicine thoracic manipulation

- YT Loose body manipulation Knee

Painful arc shoulder

- youtu.be/wU-ppPL0JpQ

- youtu.be/3LU1xsUrKV4

- youtu.be/N_Y3UoDsum4

- youtu.be/u1vhSwBgfxA

- Shoulder pain PUK

- Shoulder pain Medscape

Frozen shoulder

Lennard Funk 2008

Frozen shoulder is an extremely disabling condition, presenting with and remitting shoulder pain and stiffness.

This was well defined by Codman in 1934, who described the first and best classical diagnostic criteria still used to this day:

1. Global restriction of shoulder movement.

2. Idiopathic etiology.

3. Usually painful at the outset.

4. Normal x-ray.

5. Limitation of external rotation and elevation.

This is a distinct pathological condition identified by global limitation of glenohumeral motion, with a loss of compliance of the shoulder capsule, with no specific underlying cause found.

A secondary stiff shoulder or secondary frozen shoulder, typically presents after injury or surgery.

It may also follow an accompanying condition, such as subacromial impingement or a rotator cuff tear.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of a primary Idiopathic frozen shoulder is made on the basis of:

1. Age: Typically occurring in females more common than males, in the 4th and 5th decade.

2. Pain: The pain is of a constant nature, severe, affecting sleep. There is often a toothache pain at rest, with sharp pains with forceful movements.

3. Loss of external rotation: The typical loss of external rotation is such that passive external rotation is <60 degrees from the sagittal plane. A secondary frozen shoulder usually has restriction of external rotation, which is beyond 0 degrees (i.e. external rotation of 10 degrees as opposed to -10 degrees with a primary frozen shoulder).

Natural History: The natural history of a frozen shoulder has typically been described as passing through 3 stages over 2 years.

Stage

Duration

Symptoms

Freezing

3m

pain+ and global restriction of function

Frozen

3-9 m

pain at extreme range of movement and marked stiffness

Thawing

9-18 m

usually painless and the stiffness starts to gradual resolve at this stage

Aetiology: The frozen shoulder has been found to be more common in association with the following conditions:

1. Diabetes (10-20% association). There is a 2-4 times increased risk for diabetics of developing frozen shoulder. Insulin-dependent diabetics have a 36% chance of developing it, 10% bilaterally and the condition is more severe in diabetics.

2. Cardiac/lipid problems.

3. Epilepsy.

4. Endocrine abnormalities, particularly hypothyroidism.

5. Trauma.

6. Drugs MMPI.

Pathology: The microscopic appearance is that of thickening of the anterior capsule, particularly the middle glenohumeral ligament. There is villonodular synovitis within the rotator interval with thickening and contracture of the coracohumeral ligament. There is a reduced glenohumeral joint volume.

Coracohumeral ligament (circled) in the rotator interval, which becomes thickened and limits external rotation.

Microscopically there are 4 stages:

1. Inflammatory synovitis with capsule unaffected.

2. Proliferative synovitis, which is hypertrophic.

3. Maturation of the capsule, with reduced vascularity.

4. Burnt out synovium with a dense scar appearance.

Tim Bunker in 1995 has shown the pathology to be similar to Dupuytren’s disease with increased collagen, myofibroblast and fibroplasia.

This in association with Trisomy 7 & 8, 58% of patients who had a primary idiopathic frozen shoulder had Dupuytren’s disease elsewhere.

The inflammatory drivers for Dupuytren’s disease and frozen shoulder are similar, these being TGF-beta and PDGF.

Arthroscopy of the shoulder, showing villonodular synovitis in the rotator interval.

Treatments: The natural history of frozen shoulder is not necessarily that of complete resolution.

The original quotation that most recover from frozen shoulder originates from Codman in 1934.

However, he stated that most frozen shoulders recover compared to tuberculosis.

Many studies have shown frozen shoulder not to be an entirely self limiting condition and most patients still have some restriction of shoulder movement on resolution of the frozen shoulder but no functional disability (Grey JBJSA 1962, Shaffer JBJSA 1992, Bunker JBJSB 1995, Miller Orthopaedics 1996).

The treatment options range from:

1. Nothing.

2. Physiotherapy.

3. Distention injections.

4. Locally acting steroid injections.

5. Manipulation under anaesthetics.

6. Open/Arthroscopic capsular release.

Non-Operative Treatment: Studies on non-operative treatments for frozen shoulder have shown that physiotherapy improves range of movement but not necessarily pain relief. Steroid injections have a benefit for short-term pain relief only but no long-term pain relief

(Ryan’s Rheumatology 2005, Haslan and Celiker Rheumatol int 2001, Bulgnann Ragum Dis 1984).

Hydrodilatation has become increasingly popular recently. The procedure is performed under local anaesthetic, takes about 15 minutes to complete and the patient goes home immediately afterwards. The procedure appears to be safe with transient pain during and after the procedure being the most common complaint. Most have included corticosteroid as part of the procedure but it is not known if this is necessary. It is also not known whether arthrographic distension using steroid and saline is better than intra-articular steroid injection alone. There is some evidence that arthrographic distension provides short-term benefits in pain, range of movement and function in Frozen Shoulder. It is uncertain whether this is better than alternative interventions.

Surgery: Early surgery has been shown to be of significant benefit for a faster recovery of pain, quicker recovery of function and earlier return to work (Hill Orthopaedics 1988, Doddonhoff JSES 2000). Arthroscopic capsular release has been shown to avoid the complications of manipulation under anaesthetic. It has the advantage of being able to identify any other associated pathologies. Numerous studies have demonstrated the benefit of capsular release, although no study that we are aware of randomises patients directly comparing MUA to arthroscopic release. Our own study of 48 patients undergoing capsular release followed for 18 months, demonstrated significant improvement by 5 months postoperatively for resistant frozen shoulders. The Constant score improved from 14 preoperatively to 66 postoperatively, with 80% satisfaction. Range of movement improved significantly by 5 months (Boutros, Snow and Funk 2006).

Arthroscopic release of contracted (red) middle glenohumeral ligament.

Treatment Algorhythm. Treatment algorhythm is based on the ability of patients to cope and the significance to cope with the pain and stiffness during the stages of frozen shoulder and not based on the stage itself.

Primary idiopathic frozen shoulder is an extremely disabling condition, which does pass through a typical 3 stage progression. However, full recovery at the conclusion of the 3 phases is not common. Early surgical intervention has significant benefits for those patients that are unable to cope with non-operative treatment.

For more information see: www.shoulderdoc.co.uk

Glenohumeral instability

Dislocated shoulder

- Dislocated Shoulder Medscape

- Dislocated Shoulder Medscape

- Dislocated Shoulder Medscape

- youtu.be/CGvy6sA2OD4

- youtu.be/xDePRKeB4kc

- youtu.be/a5YRjLRz0Lo

- youtu.be/2wiIlT6_YLM

- youtu.be/jIVjVRXo79w

- youtu.be/LSW2apXq-cU

Acromioclavicular subluxation / dislocation

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

Elbow anatomy

Elbow conditions

Elbow examination

- hacking-medschool/elbow-examination

- ucsd.edu/joints4

- youtu.be/wRUkpGoiUZ8

- youtu.be/v=3s_kzqQMmNE

- youtu.be/4M_lNVlpKCQ

- youtu.be/96EMB7SWF0I

- youtu.be/zH5z3bpyuuI

Elbow assessment

Elbow & Forearm

The Elbow joint consists of the main radio-humeral hinge joint plus the ulnar-humeral and superior radio-ulnar joints which allow pronation and supination of the wrist. ( see”ottowa” elbow rules). Fractures are common but sometimes difficult to detect even on xray. Refer significant pain swelling or loss of function especially children. Myositis Ossificans not uncommon at elbow – encourage early mobilistation

Look

for injury/deformity/swelling (bony, soft tissue, fluid) redness old injury or scars skin changes (psoriasis) due to joint or other disease signs of infection or inflammation (olecramon bursitis)

Feel

Gently palpate around the elbow joint including the bony landmarks .Feel for temperature swelling tenderness bony abnormalities

Move

Quickly rule out shoulder dysfunction by asking the patient to put the hands behind the back of the head with the elbows well back.

Active Movements

The Wrist is a simple hinge joint (like the knee) and can move in one plane only.

Ask patient to bend arm as fully as possible (flexion) then straighten them out (extension) Note whether patient can extend fully.

(Note supination and pronation occurs at the superior radioulnar joint and the wrist)

Passive Movements

Repeat the above movements moving elbow yourself.

Tests of function

Ask patient to pour and drink a glass of water

Put a cardigan or coat on

Normal findings/ROM

flexion 0-140 degrees

extension 0 degrees

pronation/supination 0-180 degrees

Common abnormalities

Tennis Elbow

Golfers Elbow

Olecranon Bursitis

Pulled elbow in Children

Tennis elbow lateral epicondylitis

Tenderness at lateral epicondyle

Pain maximal on resisted wrist extension

Recovery can take weeks to months

Golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis)

Similar self-limiting condition with management as above.

Occasionally associated with ulnar neuropathy.

Olecranon bursitis

Ulnar neuritis

Elbow fractures and dislocations

(a) Supracondylar Fractures. Admit all Supracondylar fractures for Neurovascular observation.

Collar and Cuff sling +/backslab.

Never use a completed LA-POP in these patients.

(b) Radial Head Fractures. Displaced fractures may need internal fixation. Obtain orthol_paedic advice. Undisplaced # may not be visible. You should look for a + Fat-pad sign indicating Haemarthrosis.

Treat with sling. Review # Clinic 2 weeks.

(c) Pulled Elbow. e.g. Small child pulled by arm axially (e.g. in a shop).

X-Ray often unhelpful.

Reduce by pronation \ supination of elbow flexed to 90 degrees with axial compression. Normal function should return within 5¬10 mins. No review necessary.

Monteggia fracture

Colles fracture

Wrist anatomy

Wrist pain & injury

The wrist joint comprises 2 rows of 4 small carpal bones sitting in a shallow cup formed by the with radius and ulnar above and articulating with the metacarpal bones of the thumb and fingers distally. The joint allows flexion extension abduction and adductio. Pronation and supination of the wrist occur at the inferior radioulnar joint.

The wrist is vulnerable to falls on the outstretched hand, overuse injuries together with inflammatory or degenerative conditions (Rheumatoid arthritis,

Osteoarthritis, gout) and conditions peculiar to the

area conditions and other specific entities such as Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and DeQuervains Tenosynovitis

Red Flags

Grss deformity or exposure of underlying structures such as bone, nerves, tendons

Weakness or inability to move wrist, hand or fingers

Significant swelling

Pallor, coldness, numbness, or decreased pulses and capillary refill

Uncontrolled bleeding

Signs of shock

Beware Missed Scaphoid Fracture

Cervical Sponylosis can refer pain to the wrist.

Soft tissue injuries

Soft-tissue injuries of the wrist consist of sprains, strains, or dislocations. Sprains and strains are a common injury to the wrist and typically are caused by falling forward, pushing on heavy objects, or sports injuries.

Dislocation is an injury to the ligaments that surround the joint which results in separation of the aritcular surface of the joint. Dislocations to the wrist are typically caused by falls, sports injuries, or motor vehicle accidents and require immediate reduction to prevent neurovascular compromise.

Fractures

Falls on a hyper extended wrist and motor vehicle accidents cause most wrist fractures. Wrist fractures are complex because of the small size and large number of the carpal bones. The two most common fractures of the wrist are Colles fractures and fractures of the scaphoid bone. Colles fracture includes injury to the distal radius and ulna, usually caused by a fall on an outstretched hand. Scaphoid fractures are often difficult to appreciate on x-ray, therefore any “snuffbox” tenderness along with history of injury should be enough reason to apply a thumb spica splint and provide orthopedic follow-up.

Lacerations

Cuts that occur over a joint may not heal well without suturing due to the constant movement of the joint. Lacerations to the wrist should warrant assessment for nerve or tendon damange which would be identified by inability to move fingers . If assessment is positive for potential nerve or tendon damage, a referral for a hand surgeon should be arranged.

Tenosynovitis of Wrist

De Quervains Stensoing Tenovaginitis

The tendon sheath of EPB and APL of the thumb become inflamed due to overuse leading to pain and swelling on the radial side of the wrist. Resisted Abduction of the thumb is positive. (Finkelsteins test)

The wrist may be involved in OA particularly if previously damaged by fracture involving the joint surface or complications of scaphoid or lunate fractures. Active RhA may involve the wrist causing pain swelling deformity and instability and may also cause rupture of the extensor tendons at the wrist.

Hand and wrist examination

- hacking-medschool/wrist-hand

- youtu.be/65mjCLGrGTE

- youtu.be/Yw2b-c2shWE

- youtu.be/yDPt842bdic

- youtu.be/SqpPvJLNYE

- youtu.be/lYq2YihhIg

- youtu.be/dUwpNf1QSA0

- youtu.be/UFIqkMZ_l0c

- youtu.be/bovmH1-gT68

Wrist and hand injuries are common, as are infections, involvement in inflammatory or degenerative conditions (Rheumatoid arthritis, Osteoarthritis, gout) and conditions peculiar to the area (deQuervains stenosing tenovaginitis, paratendinitis crepitans, Carpal Tunnel Syndrome).

Be sure to examine all of the movements of all of the joints of the fingers and thumb

Red flags

Digital Nerve injuries often missed any alteration or difference in sensation needs referral (pencil test)

Apparently superficial injury may hide deeper damage to tendons and nerves.

Beware missing collateral and volar plate injrie to IP jointsligament

Again test sensation, explore wounds fully, and check full strength movement against resistance.

Scaphoid Injuries are still missed . Possible fractures should be referred/ sent back for review.

Grease Gun Injuries

Palm space Infections

Examination

Look for injury/deformity/swelling (bony, soft tissue, fluid) redness/ wasting of the thenar or hypothenar eminence/ old injury scarring or contracture, nail changes due to joint or other disease

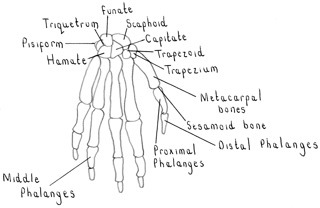

Feel Palpate around wrist and small joints of the hand: carpal bones, carpometacarpal, metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, distal interphalangeal, as well as IP joint in the thumb palpate carefully within the anatomical snuffbox in wrist injury to not miss the scaphoid(Small bones of the wrist – Scaphoid Capitate Trapezuim Trapezoid Triquetral Lunate Hamate Pisiform)

Feel for temperature swelling tenderness bony abnormalities

Squeeze across the MCP joints to detect pain +/- tenderness.

Move

Wrist Movements

With the elbows flexed at 90 degrees and held pinned to the patients side

Ask the patient to turn their palms towards the floor (pronation)

and then towards the sky (supination)

Ask the patient to adopt the prayer position (palms together – flexion)

then the inverse prayer position (backs of hands together – extension)

With the arms still tucked firmly by the sides ask the patient to move the hands apart (abduction) then together (adduction)

Movements of the thumb

Place the back of the hand on the desk (or pillow) and fix the wrist to prevent interference with movement.

Ask the patient to curl their thumb (flexion) then straighten it out (extension)

Keeping the thumb straight (uncurled) ask the patient to move the thumb away from the palm (abduction) then to the palm (adduction) then touch tips of each finger in that hand with the tip of the thumb (opposition)

Finger Movements

Ask a patient to make a fist (flexion) then open it out (extension)

Wth the palms on the desk ask the patient to spread their fingers apart (abduction) and then back together (adduction) – both movements ulnar nerve ( T1?)

PAD Palmar interossei ADDUCT

DAB Dorsal intereossei ABDUCT

Grip Strength – ask patient to squeeze your finger tightly

Passive Movements

Repeat the above movements moving the hand or digit yourself

Tests for Tendon Function and Integrity

-with the hand on the desk palm upwards, and the PIP held in extension by the examiner get the patient to actively flex the fingertip at the DIP (flexor digitorum profundus)

-next test flexor digitorum superficialis by by asking patient to actively flex each finger at the PIP whilst holding the other 3 fingers in extension

test again agains resistance if any doubt re the strenght / integrity of the tendons

Special Tests

Tinels Test – tap the flexor surface of the wrist repeatedly for 30secs to attemprt to ellicit the synptoms of CTS

Phalens – put the wrists in inverse prayer position for 60 secs to try to reproduce the symptoms of CTS

Test for the presence of myotonia by asking the patient to make a fist and

then open it quickly. A patient with myotonia will not be able to pertorm this action quickly.

Test sensation

Test the modalities of light touch, pain, vibration sense and joint position sense in both penpheral nerve and dermatome distnbutions.

Peripheral nerve distnbutions are tested as follows:

• Radial nerve: touch in the anatomical snuffbox on the dorsal aspect.

• Ulnar nerve: touch over tile medial one and a half lingers on the palm (little linger, and medial half of ring finger).

• Median nerve: touch over the lateral three and a hall fingers on the palm (lateral hall of ring linger, middle finger, Index finger and thumb).

Assess pulses

Palpate the radial and ulnar pulses. You may also wish to pertorm Allan’s test of perfusion of the hand.

Allan’s Test • Ask the patient to make a fist. • Occlude both the radial and ulnar arteries by pressing over them.

• Press for 5 seconds. • Ask the patient to open the palm and release the pressure on each artery in turn and watch the colour of the palm.

• It should change tram pale to pink as blood flow Is re-established.

Froment’s sign

To do this, ask the patient to hold a piece of paper/card between the thumbs and the radial aspect of the index finger. Then pull the paper away and ask the patient to stop it. With paralysIs ot adductor pollicis, the thumb will flex at the interphaiangeal joint.

Finklestein’s test

Ask the patient to flex their thumb. Now, ulnar deviate the wrist. Pain is indicative of De Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Types of Grip

precision grip – roll a coin between finger and thumb

ball grip – pick up a tennis ball

flat pinch hold a key between forefinger and thumb

writing – holding a pen

hook grip carrying a suitcase

unscrewing – the lid of a jar

Other Tests Of Function

ask patient to write name

fasten and unfasten a button

pour and drink a glass of water

Normal findings – ROM hand & wrist + dermatomes +/- myotomes and reflexes

Wrist :

Flexion 0-80 degrees

Extension 0-70 degrees

Abduction 0-20 degrees (radial deviation)

Adduction 0-30 degrees (ulnar deviation)

Carpometacarpal joint of thumb:

Flexion 0-15

Ext 0-20

Abduction 0-70

Plus MCP joints

Flex 0-50 thumb 0-90 fingers

Ext 0 thumb 0-20 fingers

IP joints

Flexion ip thumb 0-65 pip fingers 0-100 DIP 0-70

Extension 0-20 degrees 0 degrees 0 degrees

Common abnormalities

Osteooarthritis of the hands may produce bony swellings at the DIP (Heberdens) and the PIPs (Bouchards).

RhA produces radial deviation at the wrist, ulnar deviation of the fingers Zshaped thumbs Boutonniere and swan-neck deformity of the fingers

Dupuytrens

CTS

DeQuervains

Tenosynovitis wrist

acute tenosynovitis/tendovaginitis

Ganglion

Subcutaneous cystic swelling on the dorsum of wrist (occasionally foot and ankle).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Due to median nerve compression beneath the anterior carpal ligament (flexor retinaculum) at the wrist – causing burning, tingling or pain to the forearm, hand, wrist, and fingers (thumb, index, middle and half of the ring finger) worse at night.

There may be weakness of thumb abduction and opposition and wasting of the thenar eminence. Diagnosis supported by reproduction of symptoms in positive Phalens test (wrists fully palmar flexed for 1 minute) or Tinels Test (tapping the nerve over the tunnel at the wrist).

Risk factors include RHA pregnancy hypothyroidism menopause, gout, acromegaly. Treatment is via splinting or surgery.

Painful tingling of hands due to compression of median nerve at wrist.

May be weakness/wasting of small muscles of hand and thumb – eg opponens polliciand abductor pollicis brevis – with sensory loss over palmar aspect of thumb index middle and radial half of the ring finger.

Causes- idiopathic, pregnancy, premenstrual oedema, RhA, hypothyroidism, trauma, amyloid.

- http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00005

- DTB 2009;47:86–89

- youtu.be/u5dWTGYQ6PU

- youtu.be/xuCjuLOSFK8

- youtu.be/gLYsnD3JHfA

- youtu.be/xoeJbyR7k4Q

Scaphoid fracture

Perilunate subluxation

Perilunate subluxation capitate

Hand anatomy

- Hand anatomy Medscape

- eatonhand.com

- youtu.be/ztUdLyuYc2Q

- youtu.be/7NsRPttX2Uo

- youtu.be/P22ajLcv-h4

- youtu.be/CDKI46yPmJw

- youtu.be/vlwAoKpSI7s

Hand examination

- hacking-medschool/wrist-hand

- ucsd.edu/joints3

- youtu.be/QR151fDUQN4

- youtu.be/ysWOHe4dfpI

- youtu.be/65mjCLGrGTE

- youtu.be/bovmH1-gT68

- youtu.be/iXu8v1S__Ds

- youtu.be/REn2dlFQBzA

- youtu.be/jjofSxoCL0Q

- youtu.be/_SqpPvJLNYE

Hand injuries

- youtu.be/8MovgvhWmwg

- youtu.be/pDrAgTXEgNg

- Soft Tissue Hand Injury Medscape

- Hand Injuries PUK

- Hand Injuries I AAFP 2004

- Hand Injuries II AAFP 2004

Hand Injuries and conditions

Always record the mechanism of injury and examine and record the function of underlying flexor and extensor tendons and digital nerves.

X-Ray all wounds caused by glass to exclude the presence of retained foreign bodies. Remember that wounds caused by glass and by knife blades often extend through all soft tissues to bone.

Warn patient about jump Conduction (a completely divided nerve may continue to conduct for up to 48 hours until the distal portion degenerates). Warn also about the possibility of Delayed tendon rupture ( A partly divided tendon may later rupture when subjected to force.

Nail bed injuries These should be repaired so as to leave a flat surface, otherwise nail dystrophy will result.

Finger tip infection Paronycheal infection and pulp space infection should be drained to decompress.

Extensor avulsion Mallet & Boutonniere injuries should be treated by splintage.

Tendon Injury. Injury to tendons should be identified & treated early to minimise complications and disability.

Digital Nerve Injury

Digital Nerve injury can be referred to Plastic Surgery; consult with the on-call Plastic Surgeon in the Ulster Hospital Dundonald. For injuries to Extensor tendons or flexor injuries other than in the hand or wrist, you should seek the assistance of the Orthopaedic team here.

Arterial bleeding

Arterial bleeding emanating from the hand (or elsewhere) should be controlled by firm direct pressure with elevation. The hand should be assessed for signs of nerve injury (which is often associated) and tendon damage. If you are unfamiliar with exploration of hand wounds you should seek the help of the Surgical or Orthopaedic SHO. Bleeding should be brought under control before any transfer (e.g. to Plastic Surgery) is contemplated, but you should avoid blind application of artery forceps into the depths of a bleeding wound as this is likely to compound any neurovascular damage.

Volar Plate Avulsion Injury.

Hyperextension of a Proximal IP joint may result in tearing of the volar condensation of the joint capsule (on palmar surface). This can be accompanied by a small avulsion fracture from palmar base of middle phalynx. The injury is a significant one which will result in a haemarthrosis and can result in permanent swelling and stiffness of PIP. Irrespective of presence of # treat with Zimmer splint and review at 10 days to commence mobilisation.

High pressure jet injury.

Occurs with pressurised paint or oil sprays and will result in small puncture of finger tip with extensive spreading of irritant chemicals etc. into soft tissues and tendon sheath in hand. This injury will at first appear innocuous but will subsequently result in serious inflammation within teMon sheaths and may result in ischaemia, necrosis, dense adhesion formation and significant anatomical and functional disturbances. Admit for exploration.

Hand Splintage.

Hands should be splinted in a position of MCP flexion, lP extension using Zimmer splint (preferably on one surface only) or POP slab. Immobilise the joint on each side of the injury. Use a high sling and adequate analgesia.

Hand Injuries

Carpal

These occur with falls onto the hand. Scaphoid fracture

Diagnose clinically by tenderness in ASB and over palmar scaphoid tubercle. An X-ray should be performed to exclude other injuries and abnormalities. Apply Scaphoid POP and arrange fracture clinic referral.

Most other carpal fractures are rare, except for avulsion of dorsal aspect (with forced wrist flexion) Treat these in neutral POP

Beware Lunnate dislocation and trans-scaphoid perilunar wrist dislocation.

Hand conditions

Metacarpal fractures

Boxers fracture (5th MC neck) Scrapping x 2 weeks Refer to fracture clinic. Warn patient about residual deformity.

Displaced # I1-IV Manipulate, check X-ray, Refer # clinic. Where there is more than one fracture POP/ Vol. r slab would be appropriate.

Bennetts # These are often displaced and because of the pull of long tendons may be difficult to reduce. If so internal fixation may be appropriate

OA hands

OA thumb

OA at the base of the thumb BMJ Nov 2011

Dupuytrens contracture

Palpable thickening, fibrosis and contracture of palmar fascial aponeurosis and tendons causing flexion deformities of MCP joints espescially ring and middle fingers.

Causes

Idiopathic and familial

Traumatic/Occupational – gardeners – vibrating machines

Epilepsy

RhA

Liver disease espescially portal hypertension

Xiapex (clostridium histolyticum)

Trigger finger/thumb

Idiopathic thickening – with nodule formation – of fibrous flexor sheath at base of finger (or thumb). The thickened tendon or nodule becomes stuck in the tendon sheath when the finger is flexed – and the finger has to be released by passively extending the digit using the other hand.

Volkmanns ischaemic contracture

Finger injuries

Injuries to the fingers occur frequently during sports activities and within a variety of occupational settings. The most common injuries include fractures, dislocations and lacerations. Proper evaluation, treatment and referral are necessary to prevent improper healing and loss of function of the digits.

Red Flags

Amputation

Signs/symptoms of shock

Signs of neurovascular compromise – pallor, loss of sensation, cold digit

Missed Collateral ligament rupture

Traumatic finger injuries include lacerations, dislocations, tendon/ligament disruptions and fractures. The most common injuries will be discussed below.

Key anatomy of the fingers include the bones: proximal, middle, and distal phalanges (the thumb has only proximal and distal); and the three joints of the fingers: the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) is the knuckle of the hand; the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.

Extensor tendons are located on the dorsal aspect of the hand whereas the flexor tendons are located on the palmar or volar aspect.

Lacerations

Lacerations involving the digits occur frequently and may be simple or complex. Wounds must be copiously irrigated and explored in a bloodless field (use a tourniquet if necessary but always ensure this is removed!) and the affected finger moved through full range of motion to evaluate for tendon, ligament, muscle or bone injury.

Simple lacerations may be closed using proper techniques.

Complex lacerations involving underlying structures require consultation with a hand surgeon for immediate or delayed repair. Lacerations involving the fingernail may involve the nail bed. Such injury may require nail removal and repair of the nail bed injury.

Dislocations

Dislocations of the PIP joint are common – often from a ball striking the end of an extended digit. Most can be reduced by traction. Athletes may present with history of dislocation that was reduced by the player or coach. These still need to be X-rayed and splinted even if the gross appearance of the digit is normal. DIP joint dislocations are uncommon and often are accompanied by significant fracture around the joint, requiring evaluation by hand surgery.

Tendon and ligament disruptions

One of the most common tendon injuries to the digits is known as mallet finger. The patient will present with the tip of the finger in flexion, with inability to straighten at the DIP joint. This often occurs when a ball strikes the tip of a flexed finger. X-rays and splinting the finger in full extension is necessary with close orthopedic follow up.

Skier’s or gamekeeper’s thumb occurs when the thumb is bent backward (acutely abducted) during a fall and injures the ulnar collateral ligament – a ligament running along the base of the thumb. These injuries must be x-rayed, placed in a spica splint and sent for orthopedic referral.

Fractures

Fractures of the fingers occur from a variety of forces including crush injuries and hyperextension/flexion of the interphalangeal(IP) joints. Avulsion fractures are common at the IP joints and may be difficult to detect on X-rays. Distal phalanx or “tuft” fractures that do not involve the joint and phalangeal shaft fractures may be managed by splinting alone. Fractures involving large avulsions at the joint or the joint itself mandate splinting and orthopedic referral.

Other Injuries

Subungual hematoma is bleeding under the fingernail, usually secondary to crush injury. If the patient presents within a few hours of injury, the blood can be drained from under the nail by means of an electro-cautery device or by boring an 18 gauge needle through the nail until blood spontaneously drains from the opening.

Paronychia is an infection along the border of the fingernail. This occurs more frequently in patients who bite their nails. Treatment includes incision and drainage of the infected space, warm soaks and antibiotics.

Felon is an infection of the finger pad, or the distal fleshy aspect of the finger opposite of the fingernail. This is often caused by a puncture wound which becomes secondarily infected. Incision, drainage and antibiotics with close follow up for re-evaluation are crucial aspects of care.

Test full range of motion of affected digit, compare to opposite hand

Neurovascular exam – including 2 point discrimination (use a paper clip – normal range for fingertip is 2-5mm); extending wrist and fingers (radial nerve); spreading fingers against resistance (ulnar nerve); opposing the thumb against resistance (median nerve); capillary refill and radial/ulnar pulses.

X-ray – before and after reduction

Finger fracture

Check for rotational deformity which is particularily likely in fractures of proximal phalynx. Following reduction check X-Ray in splint. Splint hands with MCP Flexion and IP Extension. If reduction is unstable or not possible (eg due to interposition of soft tissues) get orthopaedic advice re? admission for internal fixation. See section on Hand Injuries

Finger tip injury

In Children treat these conservatively with Steristrips and Occlusive dressings (e.g. Flammazine). Suturing is normally not necessary.

In adults use Digital Nerve Block to ensure wound is cleaned thoroughly. Where bone is protruding this would usually require trimming to obtain soft-tissue cover.

Mallet finger

These should be kept in extension in a mallet splint for 6 weeks with 4 weeks night splintage thereafter if successful. Instruct patient to keep splint on and dry. Refer to fracture clinic.

Ring removal

Removal of a ring from a digit may be necessary if a patient is unable to remove the ring and has impending or existing swelling of the digit or surrounding area or is developing numbness or impaired circulation to the digit. A ring which becomes too tight can cause sufficient pressure on the digit arteries to cut off the circulation to the digit distal to the ring and in extreme circumstances this could lead to loss of the digit.

Digit swelling may be secondary to trauma to the digit itself or to a more proximal part of the extremity, or as a result of soft tissue swelling such as in congestive heart failure, fluid retention in pregnancy or inflammatory processes such as arthritis.

Key Issues

Red Flag Warnings

Pallor, numbness, coldness, decrease or absent pulses in the digit

Decreased capillary refill

Severe pain

More proximal swelling which could extent to the digit over time

Immediate Care Considerations

Assess neurovascular status of the digit

Capillary refill

Digital pulses

Sensation

Elevate affected area

Ice affected area

Stabilize and immobilize affected area if trauma suspected

Background Information

Timely removal of a ring is important. It is better to remove a ring before it has become too tight than to wait for this to happen. This could prevent a trip to A&E during the night!

Many injuries cause swelling and even if the injury is not to the digit itself, the digits may swell secondarily. The same applies to swelling arising for other reasons. If a ring becomes tight this can lead to nerve or vascular injury with impairment of sensation of circulation and in extreme cases loss of the digit as a result. Neurovascular status of the digit should be assessed before and after removing the ring.

When assessing neurovascular compromise keep in mind the 5 P’s

pain,

pallor,

pulses,

paraesthesia,

and paralysis.

Follow your own departmental policy on obtaining signed consent for removal of the ring and documentation of the ring being returned to the patient.

Ring Removal Techniques

There are various techniques for ring removal.

The more commonly used are 1) ring cutting and 2) string wrap or pull technique.

When preparing to remove a ring keep in mind the urgency of the situation. If the patient’s circulation is compromised the first priority is the well being of the patient not the integrity of the ring. If the patient is not compromised in any way you can then take into account the value of the ring.

Ring cutting is typically used if the ring is thin and metal. This ring cutting tool has a special blade guard but the operator should be familiar with how to set up and use the tool ensuring that the guard is aligned properly so it will not cut/abrade the skin. Some ring cutters are manually operated while others may have an electric motor. Ring cutting kits sometimes include different blades for different metals, and if so it is important to ask the patient what type of metal their ring is made from and to use the correct blade. If the ring is loose enough for you to be able to identify the metal hall mark, the patient may appreciate you avoiding cutting through this as it will help retain the value of the ring. Be sensitive to the emotional connotations of cutting through a ring such as a wedding ring. Advise the patient of the consequences of non removal and reassure the likelihood of invisible repair.

The string technique is performed as follows:

Slip a piece of string under the ring while moving the ring toward the hand

The remainder of the string is then wound around the swollen part of the finger distal to the ring a number of times ((and soap applied ?))

The string is now unwound from the hand side pushing the ring forwards towards the tip of the finger

Repeat this process gradually easing the ring towards the finger tip to complete removal

Investigations

X-ray according to nature of any trauma or examination findings.

Treatments

Rest, ice, and elevate – while in the department and at home afterwards

Pain relief as required

Consider antihistamine (for swelling associated with insect bite/stings)

Consider the need for tetanus immunization if skin integrity is breeched

Discharge and Follow Up Considerations

Advise the patient to report any changes in sensation, color, temperature, or any increase in pain.

Hip / groin exam

- hacking-medschool/groin-exam

- ucsd.edu/joints5

- youtu.be/VuHsa4kxT0s

- youtu.be/4IYgyXMpfik

- youtu.be/5LNYdJIrWYo

- youtu.be/FyFFnW5_qms

Hip Thigh Pelvis

The hip is a stable ball and socket joint surrounded and stablised by a large muscle mass. Injuries include FNOF in elderly, Hamstring tears and haematomas.

Common atraumatic conditions are OA hip, trochanteric bursitis.

Red flags

Hip pathology may present with knee pain as they share obturator and femoral nerve supply.

Beware Child with spontaneous limp – often transient synovitis of hip but sometimes SUFE (teenager) or Perthes (5-9 years)

Beware quads/patellar injury after minor injury or stumble in elderly – refer if cant SLR.

Examination

Undress patient down to underwear. Use blanket for modesty. Patient standing initially.

Inspect

front and back – deformity, scars, soft tissue or bony swelling, level of iliac crests, raised gluteal folds

Examine gait pattern, use of walking aid, stride length, pain.

Palpate

Bony landmarks ASIS Ischial spine greater trochanter

Move

With the patient supine

Fix the pelvis by placing your hand on the opposite iliac crest – so that movements are indeed from the hip and not the pelvis

Flexion – ask the patient to bring the heel up to the bottom

Abduction – ask the patient to move the straight leg away from the midline

Adduction – ask the patient to move the straight leg across the midline

Ask the patient to roll over so they are now prone

then raise each leg off the bed

ask the patient to keep the knees together and rotate the ankles outwards then inwards

Repeat Active Movements

Special tests

Trendelenburg test

• Observe the patient from behind.

Ask them to support their weight on the right hip only (ie ask them to lift the left leg off the ground by bending the knee).

• Watch the pelvis, and note the direction of tilt. (In nonmal individuals, the pelvis will rise on the side of the leg that has been lifted. With instability, the pelvis may drop on the side of the leg that has been lifted.) Repeat the test, with the patient standing on the other leg.

Thomas’ test

• Put your left hand (palm upwards) beneath the lumbar spine to ensure that the lumbar spine remains flattened during the test.

• With the other hand, passively flex one hip.

• While you are flexing this hip, observe the movement of the other leg – in the event of a fixed flexion deformity (common in hip osteoarthritis), the opposite leg flexes too. Repeat other side.

Test function

Gait Should have been assessed earlier in your examination.

Normal findings/ROM

flexion 0-120 degrees

ext 0-20 degrees

abduction 0-45 degrees

adduction 0-30 degrees

medial rotat 0-35 degrees

lateral rotat 0-35 degrees

Groin Exam — hernia scrotum

Thigh Exam

Femur + surrounding muscles + soft tissues -Quadriceps anteriorly and hamstrings posteriorly

Soft tissue injuries.

The groups of muscles located in the back of the thigh are the hamstrings and are commonly sprained or strained in athletes or sports injury. A hamstring injury typically occurs when the knee is extended and the hip flexed as the person falls forward.

The anterior groups of thigh muscles are the quadriceps. The rectus femorus muscle tear and groin strain are the two most common injuries with the quadriceps. Clinical manifestations of strains and sprains are similar and most are self-limiting with full function restored in 3 to 6 weeks.

Blunt Injury/Lacerations

Lacerations that occur to the thigh may be minor cuts or abrasions or major penetrating injuries such as gunshots, knife wounds, or foreign bodies such as tree branches from a fall or glass. When these types of injuries occur the depth of the injury as well as possible damage to the underlying structures (arteries, nerves, tendons, and ligaments) should be considered.

Thigh Adductors

Observe three ducks pecking grass

Obturator, three adductors (longus, brevis, magnus) Pectineus Gracilus (Obturator, femoral plus sciatic nerves)

Hamstrings (posterior compartment)

Big fat swotty Samantha ate my hamsters pens (Khalid Khan Mnemonics & Study Tips For Medical Students)

Biceps femoris, Semitendinosous Semimembranous Adductor Muscle Hamstring Portion

Say Grace Before Tea

Sartorious & Gracilis Before Semitendinosus

Hip and groin conditions

- Medscape Groin injuries

- Medscape Hip Tendonitis and Bursitis

- Medscape Ilopsoas Tendinosis

- Medscape Adductor Strain

- Medscape Hip Pointers

- Osteitis Pubis

- hipandgroinclinic.ie hip arthroscopy

- london hip arthroscopy centre hip-and-groin-conditions-labrum

- cjsmblog.com hip and groin conditions

- manchester hip arthroscopy.com hip-conditions

Lower limb injuries

Tibia

Tibial fractures should normally be admitted after consultation with the staff of the Orthopaedic Unit. Immobilisation prior to fixation may be achieved with a Frac Pac or POP slab.

Ankle

Minor fractures can be managed with Wool/Crepe bandaging and NWB with crutches. Encourage elevation.

For Displaced/ Bilateral/ Subtalar joint injury admit for elevation as these invariably swell considerably. Do not apply POP initially. With os calcis fractures ensure that your examination excludes fractures of the proximal skeleton e.g.. Knee, hip, spine

Pelvis

Admit pelvic fractures.

For high velocity injuries remember the possibility of urethral and vascular injury. Pelvic injuries may be masked in patients with other painful injuries and in those with multiple injuries.

In serious trauma a pelvic X-Ray should be done as a routine as pelvic injury may be concealed, is common, and can result in considerable concealed blood loss.

Ankle Pilon Fracture

Fractures Os Calcis?

FNOF Hip Fracture

Fractured Femur

OA hip

Elderly patient with slowly progressive pain and stiffness in hip, groin, anterior thigh (and often knee). Worse on movement relieved by rest.

- OA PUK

- AO AR UK

- Hip OA Orthopaedic weblinks

- youtu.be/om7y1IZIiPU

- youtu.be/8qcBKF-Jo4M

- youtu.be/r8mS4y0EmAw

OA hip management

Femoral acetabular impingement

- youtu.be/R4_3Fem4bM0

- youtu.be/JOqKKe-euIY

- youtu.be/Ggx7H58DI6k

- youtu.be/_BIko1erlCA

- youtu.be/7N0Zrd-F42Q

- youtu.be/k9BduZUbrXY

- youtu.be/nGA5Tpp77hk

- youtu.be/Rtp4oz0_3YY

Lateral hip pain trochanteric bursitis

Ischial Bursitis

- physioadvisor.com.au ischial bursitis

- Bursitis Medscape

- Bursitis in Emergency Medicine Medscape

- youtu.be/4uyOVvdlKdU

Piriformis

hacking-medschoo/piriformis-syndrome

Meralgia paraesthetica

Pins and needles and numbness along the lat side of the thigh due the entrapment of the lat cutaneous nerve of the thigh between the two fibres of the inguinal lig at the ant sup iliac spine (ASIS).

Rx: steroid injection and if it fails then operation

Usually pregnant or otherwise gaining weight

Thigh Pain Lateral thigh pain:

DD – trochanteric bursitis and meralgia paraesthetica

Trochanteric bursitis: pt c/o pain around the hip area but more pointing towards the upper lat aspect of the thigh, unable to lie on the effected side, pain on walking and getting up, may mimic hip arthritis.

Inv: none – clinical diagnosis mainly

Rx: nsaid, capsaicin cream and steroid injection which might need to be repeated.

Hamstring injury

Knee anatomy

Knee examination

The knee is a major weight bearing joint which relies on dynamic muscle contraction and intact ligaments for its stability.

Knee injuries injuries are common, and can often be correctly diagnosed by detailed attention to the history.

If there is full movement and the patient can weight bear the likely diagnosis is a simple sprain or contusion.

Rapid onset of swelling, locking + giving way (loose body) , inability to extend fully or weight bear are suggestive of more serious pathology.

Red flags

Beware Pain referred from hip and lower back

Rupture of Quadriceps tendon / patella tendon – always SLR

All effusions are significant and should be reviewed.

Meniscal and anterior cruciate ligament injuries are often missed at first presentation.

Examination

Expose both knees adequately. Clarify main site of pain.

Look

Observe gait

On the couch inspect in close detail for scars, small volumes of fluid, cysts, quadriceps muscle wasting (especillly medially) deformity/swelling (bony, soft tissue, fluid) redness or heat ( gout , prepaellar bursitis, septic arthritis) Q angle

Compare alignment and contours of knees

Feel

Palpate for heat and warmth swelling tenderness bony abnormality

palpate along the the quadriceps tendon, patella and patellar tendon

Palpate along the joint line (ask the patient to bend the knee slightly to identify this)

Palpate the patellofemoral joint, including beneath the patella for crepitus

Palpate the medial and collateral ligaments

Medial and lateral menisci

Milk bursa and patellar tap or bulge sign

Test for the presence of a joint effusion, using either the bulge test (if a little fluid is present) or the patellar tap test (for a larger volume of fluid).

Bulge test

Using the curve formed between your extended thumb and Index finger, milk down any fluid from above the knee.

Using your index and middle fingers together as a unit, sweep any fluid along the medial aspect of the knee. Then sweep along the lateral side of the knee, and watch to see if a bulge occurs on the opposite side

Move

Active Movements

Flexion Ask the patient to bend their knee to their buttock

Extension Ask the patient to straighten their leg fully

Passive Movements

Repeat the above movements moving the knee yourself.

Special Tests

Collateral ligaments

Lateral Collateral – flex knee to 30 degrees Support the medial aspect of the thigh, and push medially on the lower leg Medial Collateralhen – support the lateral aspect of the thigh, and push laterally on the lower leg

Excessive movement indicates ligament damage.

Cruciate ligaments

Anterior and posterior drawer tests

With the patient supine and relaxed on the couch. ask them to flex their knee to about 15 degrees

Palpate the bulk of the quadriceps muscles to ensure that the patient is relaxed.

Stabilise patients foot by sitting on it on couch ( make sure not painful!)

With the fingers of both hands round the back of the knee, keeping the thumbs in front over the patella. Position the thumbs so they point directly towards the ceiling.

Pull/push the unit you have formed with your hands forward and backward to test the anterior and posterior cruciates

Excessive movement indicates ligament damage.

Meniscal Tests (Apley’s grinding test)

Ask the patient to lie prone (face down) with the knee flexed to 90 degrees.

Use your left hand to stabilise the lower leg behind the knee and with the right hand grip the heel of the foot.

Twist the foot in a ‘grinding motion’.

A grinding sensation or pain indicates meniscal damage.

Tests of ligament integrity

Adduction stress test (medial collateral ligament)

Abduction stress test (lateral collateral ligament)

Anterior draw test (anterior cruciate)

Posterior draw test posterior cruciate

McMurrys (rotation of tibia on menisci at 90 degrees) or Aspleys grind and distraction tests

Rotation of foot

Normal findings – ROM

flexion 0-140 degrees

extension 0 degree

Common abnormalities/conditions

Chondromalacia

OA

Prepatellar Bursitis

Septic Arthritis

Gout

Meniscal Injury – follows sudden forced rotation of the upper leg (ie tibia) on a fixed lower limb tearing the meniscus sitting on the tibia

ACL – as above with associated high velocity impact to the side of the knee (loud pop, inability to weight bear immediately, immediate swelling within minutes- 1hr)

Investigations

Traumatic injuries may need referral for Xray if:

age>55, isolated patellar tenderness, tenderness over head of fibula, inability to flex to 90 degrees, inability to weight bear at time of injury and at examination.

WCC/ESR/CRP Rheumatoid screen again depending on clinical history and finding

- youtube.com/watch?v=eRPvoNe9Aho

- youtu.be/W5T42dFYaOg

- youtu.be/W5T42dFYaOg

- youtu.be/Irg3Cb4JaE8

- youtu.be/bHytLhg-1vM

- youtu.be/yQdBrr3Mmj0

- youtu.be/28mJFyHMXHo

- www.youtu.be/i-nFGqwr_VE

- www.youtu.be/fxKCDkOiJs

- www.youtu.be/ubP-1WaFeEc

Knee Special Tests

- youtu.be/vvebjHOjiLc

- youtu.be/dH_jnTy1rNk

- youtu.be/yOztSsiL2ng

- youtu.be/fkt1TOn1UfI

- youtu.be/w57I1cYXlCA

Calf Examination

Knee pain and injuries

Knee mechanisms of injury

Ottowa knee rule

Fractured Patella

youtu.be/Qe6VNxxOJaw

Fractured tibial plateau

Cruciate ligament Injuries

xxx

Osteochondritis dissecans

- Osteochondritis dissicans Medscape

- youtu.be/kPpLEfQBJfQ

- youtu.be/tAYvkMVr9Sk

- youtu.be/cjJz91R9Yg0

- youtu.be/l5rBhmgnCds

Anterior knee pain

Causes

chondromalacia patella (patellofemoral overload)

jumper’s knee,

prepatellar bursitis

PFD

Often teenage girls or athletes, c/o pain over the front of the knee or underneath the knee-cap, may be triggered by simple injury, pain is always worse on climbing up and down the stairs or when standing up after prolonged sitting, knee may give way or swells up, it sometimes catches but there is no true locking and it is often bilateral.

The knee may look normal but careful examination may reveal misalignment and quads wasting. Patella will be tender at the edges and Clark test (sharp pain when patella is forcibly pressed against femur and pt contracts the quad muscle suddenly) is +ve.

Rx – quad drill(stretching) exercises and physio usually cure the problem but remind the patient that it will take time. Refer to ortho if conservative Rx fails.

Infrapatellar bursitis may need aspiration and steroid injection

Q angle

OA Knee

Slowly progressive pain and stiffness precipitated both by activity and restriction of movement (cinema sign).

Patient may be obese and/or have history of previous injury/surgery/ or inflammatory arthritis some years previously

Exercises OA knee

Surgery for OA Knee

- youtu.be/MyO_eJLmZ5g

- youtu.be/uoL35NJz86w

- youtu.be/fyxDS9eCvVA

- youtu.be/dCBeGDCYVNk

- youtu.be/XwSa_hoCazs

NZ joint replacement criteria

Table NZ Priority criteria for major joint replacement (maximum score 100)

Pain (40%)

Degree (patient must be on maximum medical therapy at time of rating):

None 0

Mild: slight or occasional pain; patient has not altered patterns of activity or work 4

Mild-moderate: moderate or frequent pain; patient has not altered patterns of activity or work 6

Moderate: patient is active but has had to modify or give up some activities because of pain 9

Moderate-severe: fairly severe pain with substantially limited activities 14

Severe:major pain and serious limitation 20

Occurrence:

None or with first steps only 0

Only after long walks (30 minutes) 4

With all walking, mostly day pain 10

Significant, regular night pain 20

Functional activity (20%)

Time walked:

Unlimited 0

31-60 minutes (eg longer shopping trips to mall) 2

11-30minutes (eg gardening, grocery shopping) 4

2-10 minutes (eg trip to letter box) 6

<2 minutes or indoors only (more or less house bound) 8

Unable to walk 10

Other functional limitations (eg putting on shoes, managing stairs, sitting to standing, sexual activity, recreation or hobbies, walking aids needed):

None 0

Mild 2

Moderate 4

Severe 10

Movement and deformity (20%)

Pain on examination (overall results are both active and passive range of motion):

None 0

Mild 2

Moderate 5

Severe 10

Other abnormal findings (limited to orthopaedic problems eg reduced range of motion, deformity, limp, instability, progressive x ray findings):

None 0

Mild 2

Moderate 5

Severe 10

Other factors (20%)

Multiple joint disease:

No, single joint 0

Yes, each affected joint mild: moderate in severity 4

Yes, severe involvement (eg severe rheumatoid arthritis) 10

Ability to work, give care to dependants, live independently (difficulty must be related to affected joint):

Not threatened or difficult 0

Not threatened but more difficult 4

Threatened but not immediately 6

Immediately threatened 10

Total score (> 70 = priority for joint replacement)

The New Zealand priority criteria scoring system for hip and knee replacement is used by many PCTs to triage those patients who may require joint replacement.

A score > 70 makes the patient a priority for joint replacement

BMJ 1997;314:131 (11 January) The New Zealand priority criteria project.

Bow legs and knock knees

Occurs due to changes in the tibiofemoral angle during growth.

Often, a varus or valgus position isaccentuated by internal or external rotation of the tibiae, respectively.

This rotation is due to the uneven growth of the tibia and fibula, and disappears spontaneously during normal development.

A varus position during a child’s first 2 years is normal (distance between the knees of 10 cm or less),

At 7 years of age, the intermalleolar distance is normally less than 2.5 cm, with a maximum of 8 cm. A larger distance indicates a valgus position, which may require treatment.