20

| Paeds vital signs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | RR | HR | Weight | BP |

| 1-12w Newborn | 100-220 | 3.5 kg | ||

| 0-1y infant | 30–60 | 6m 7.5 kg1 Year 10kg | >60 | |

| 1-3y toddler | 24–40 | 90-150 | >70 | |

| 3-6y preschool | 22–34 | 80-140 | 5 Years 20kg | >75 |

| 6-12y school age | 18–30 | 70-120 | 10 Years 35kg | >80 |

| 12–16y adolescent | 12-18 | 60-100 | >90 | |

| Wt = (age+4)*2 |

| SBP = 80 + 2 X years of age |

Pulse rates for a child who is sleeping may be 10 percent lower than the low rate listed.

In infants and children aged three years or younger, the presence of a strong central pulse should be substituted for a blood pressure reading

hacking-medschool/paeds-vital-signs

| GCS children under 4 | |

|---|---|

| Eye Opening | |

| Spontaneously | 4 |

| To verbal stimuli | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| No response to pain | 1 |

| Best motor response | |

| Spontaneous or obeys verbal command | 6 |

| Localises to pain or withdraws to touch | 5 |

| Withdraws from pain | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion to pain (decorticate) | 3 |

| Abnormal extension to pain (decerebrate) | 2 |

| No response to pain | 1 |

| Best verbal response | |

| Alert, babbles, coos, words to usual ability | 5 |

| Less than usual words, spontaneous irritable cry | 4 |

| Cries only to pain | 3 |

| Moans to pain | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| Conscious level AVPU | |

|---|---|

| A | Alert |

| V | Responds to Voice commands |

| P | Responds to Pain |

| U | Unresponsive |

| PEWS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour | CVS | Resps | |

| lethargic confused or reduced pain response | grey CRT>5 tachycardia +30 or bradycardia | 5 below normal with retractions +/- >50% FiO2 | 3 |

| irritable agitated and inconsolable | CRT 4 tachycardia + 20 | >20 above normal using accessory muscles 40-49% FiO2 or >3 LPM | 2 |

| sleeping or irritable and consolable | pale or CRT 3s | >10 above normal using accessory muscles 24-40% FiO2 or >2 LPM any initiation of O2 | 1 |

| playing appropraite | Pink CRT 1-2s | WNL for age no retractions | 0 |

| Add 2 pts for frequent interventions (suction, positioning, O2 changes or multiple IV attempts>7 assess every 30m6 assess every hr5 assess every 1-2 hrs0-4 asses every 4 hrsParental concern should be an automatic call to RRTchoa.org/PEWS | |||

Babycheck pamphlet for parents

General assessment

Observe the child from a distance whilst obtaining the history.

The child’s interest/trust can be gained and information obtained by giving them a toy, tongue depressor whatever whilst talking to the parents

Children who are truly sick tend to be preoccupied, uninterested and unsmiling, and usually the parent/guardian will have noticed these changes

If you (with the parent) decide that such changes are very marked, then they alone could be sufficient criteria for urgent referral

In most circumstances there will be accompanying signs and these should be sought. Examination should cover the child’s airway and breathing, circulation

and neurological signs together with some assessment of the child’s general appearance. It is particularly important to check for features suggesting very

serious illness (preterminal signs).

It is also important to recognise that if a child is clearly ill, but you can find no abnormality of airway, breathing, circulation or conscious level, referral for a second opinion is still appropriate although it may be less urgent. (source?)

Airways and breathing

Check for features of altered respiratory work

recession/use of accessory muscles

flaring of alae nasae

grunting

stridor/wheeze

positioning, eg ‘tripod position’ to splint the chest wall

increased respiratory rate

exhaustion (this is a preterminal sign).

Assess the efficiency of breathing. – using stethoscope and pulse oximeter.

A silent chest is a pre-terminal sign.

Look for the effects of respiratory failure on other organs

cyanosis (another pre-terminal sign)

tachycardia

bradycardia (preterminal sign)

agitation, confusion or drowsiness.

Circulation

Check HR, pulse volume and capillary refill (press on the skin over the sternum for 5 seconds – in a healthy child the blanched area will re-perfuse in less than 2 seconds).

BP drops late in most conditions and, in itself, is of limited value as other signs should be present. Hypotension is a pre-terminal sign.

Look for the effects of circulatory failure on other organs

tachypnoea without recession

pallor

agitation then drowsiness

profuse sweating.

Posture and tone – normal / floppy / increased tone.

Features of meningitis such as neck stiffness or irritability (a child may be upset by being handled).

Abnormal movements.

Pupils particularly reaction to light.

Skin and mucous membranes

Look for changes in the skin and mucous membranes

petechial or purpuric rash

bruising

oedema

signs of dehydration

| Paeds fluid and electrolyte requirements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Daily Requirement | 2500 ml/day | c 35ml/kg/day 100ml/kg first 10kg plus 50ml/kg/day next 10 kg plus 20ml/kg/day beyond |

| urine losses | 800-1500 ml | |

| stool losses | 250 ml | |

| insensible loss | 600-900 ml | increased by 10% for each degree of fever decreased on ventilator |

| Na | ||

| Total Daily Maintenance Requirements | |

|---|---|

| up to 10kg body weight | 100 mL/kg/day |

| plus from 11 to 20kg | 50 mL/kg/day |

| plus from 21 to 70kg | 20 mL/kg/day |

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| mild | 3-5% of body wt. = 30 -50ml/kg |

| moderate | 6-9% of body wt. = 60 90ml/kg |

| severe | 10-15% of body wt = 100-150ml/kg |

| Oral rehydration |

|---|

| eg dioralyte 120-150ml/kg/day (2-2.5oz./lb/day) maintenance plus replace deficits. |

| Give in small, very frequent amounts. Emphasise importance of fluid replacement to parents |

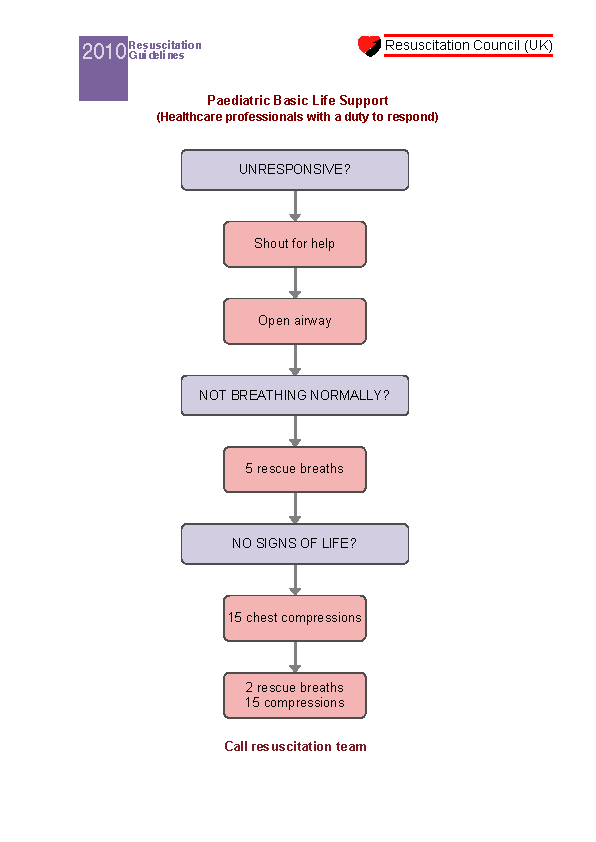

Paeds BLS

How to rescuscitate a child NHS Choices

http://www.cprdude.com/default.shtml

Palpating brachial artery in kids

Paediatric Nursing Procedures Google books

Paeds chin lift

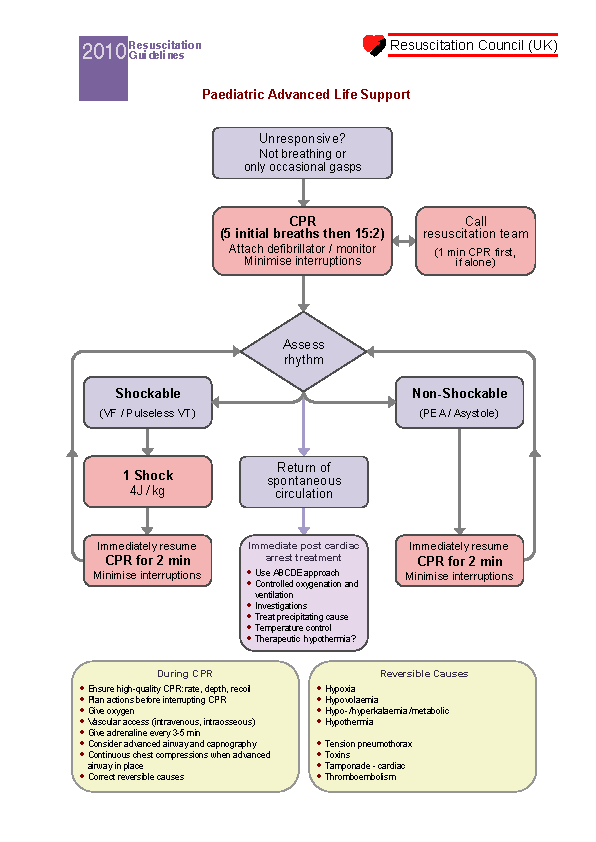

Paeds ALS

Paeds ET tubes and laryngoscopes

Anaphylaxis Treatment Algorithm for Children

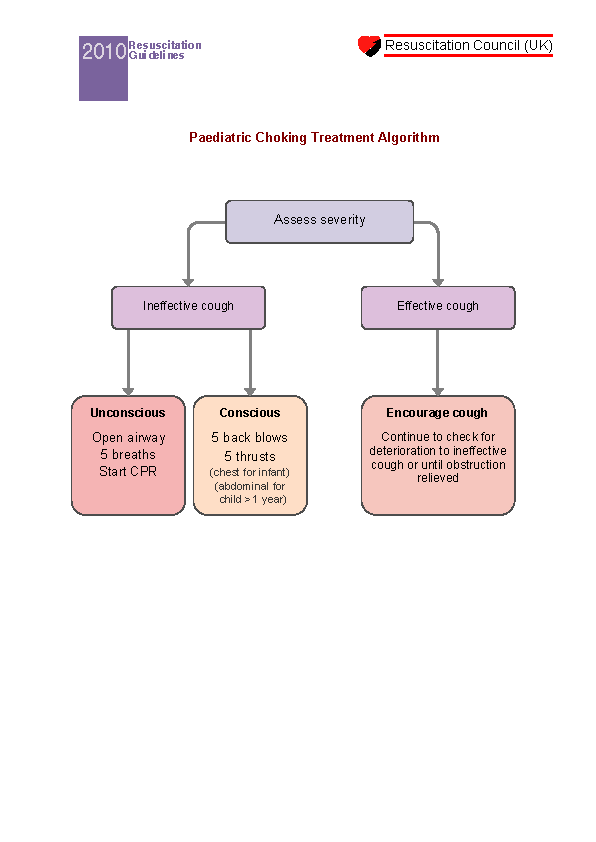

Choking child and infant

Drowning child

| Paeds doses (APLSG) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | mean weight (kg) | % adult dose |

| Newborn | 3.5 | 12.5% |

| 2 month | 4.5 | |

| 3 months | 6 | |

| 4 month | 6.5 | 20% |

| 6 months | 8 | |

| 9 months | 9 | |

| 1 year | 10 | 25% |

| 2 years | 12 | |

| 3 years | 15 | 33.3% |

| 4 years | 16 | |

| 6 years | 20 | |

| 7 years | 23 | 50% |

| 8 years | 25 | |

| 10 | 30 | 60% |

| 12 | 40 | 75% |

| 14 | 50 | 80% |

| 16 | 60 | 90% |

| Adult | 70 | 100% |

| Paediatric Weight = (age+4)*2 |

Paeds acute severe asthma

For Children admission should be arranged when there is:

• Failure to respond or early deterioration following bronchodilator (Peak flow < 50% expected 10 mins after Rx),

• GP request for admission,

• Severe breathlessness or tiredness,

• or difficulty at home with Rx.

Acute asthma paeds under 2

Assessment of acute asthma in early childhood can be difficult. Intermittent wheezing attacks are usually due to viral infection and the response to asthma medication is inconsistent. Wheeze frequently occurs in the absence of a prior diagnosis of asthma and may be due to viral infections, bronchiolitis, asthma, aspiration pneumonitis, pneumonia, tracheomalacia or complications of underlying conditions such as cystic fibrosis or congenital anomalies

Management

Moderate Severe Life threatening

Give: b2 agonist up to 10 puffs via spacer ± face mask or nebuliser

If known asthmatic add prednisolone 10mg daily

While awaiting transfer give: Oxygen via facemask ?2 agonist up to10 puffs via spacer ± face mask or nebulised salbutamol 2.5mg or terbutaline 5mg

Refer urgently (???) if: SpO2 is known to be <92% pre-treatment

the child deteriorates and

has features of life threatening or severe asthma

you are concerned about the parent’s ability to recognise deterioration and/or manage care at home

If poor response add nebulised ipratropium 250micrograms

If not referred advise the parents on what to do if the child deteriorates and review the child regularly

Acute asthma paeds over 5

| Moderate | Severe | Life-threatening | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEF | >50% | 33-50% | <33% |

| Speech | Normal | cant complete sentences | Silent chest, cyanosis poor respiratory effort |

| Pulse | <110 bpm | >110 bpm | Bradycardia, dysrhythmia, or hypotension |

| Respiratory rate | <25/min | >25/min | Exhaustion, confusion, or coma |

| SpO2 | >92% | <92% | <92% |

When measuring PEF use best or predicted value

Moderate

Give: a ?2 agonist 2-4 puffs via spacer ± face mask

Consider soluble prednisolone 30- 40mg

Increase ?2 agonist dose by 2 puffs every 2 minutes up to 10 puffs according to response

If poor response refer to hospital urgently (???)

Severe

Give: oxygen via face mask

?2 agonist 10 puffs via spacer ± face mask or nebulised salbutamol 2.5-5mg, or terbutaline 5-10mg AND soluble prednisolone 30-40mg

Assess response to treatment 15minutes after ?2 agonist

If poor response repeat ?2 agonist and refer to hospital immediately (????)

Life threatening

Refer to hospital immediately (????).

While awaiting transfer give: oxygen via face mask

AND nebulised (preferably on oxygen) salbutamol 5mg or terbutaline 10mg AND nebulised ipratropium 250micrograms

AND soluble prednisolone 30-40mg or IV hydrocortisone 100mg

Repeat ?2 agonist via oxygen driven nebuliser

If good response continue up to 10 puffs of nebulised ?2 agonist as needed (up to 4 hourly).

If symptoms are not controlled repeat ?2 agonist and refer to hospital urgently (???)

Continue prednisolone for up to 3 days

Arrange follow-up visit to clinic

Nebuliser vs MDI + Spacer

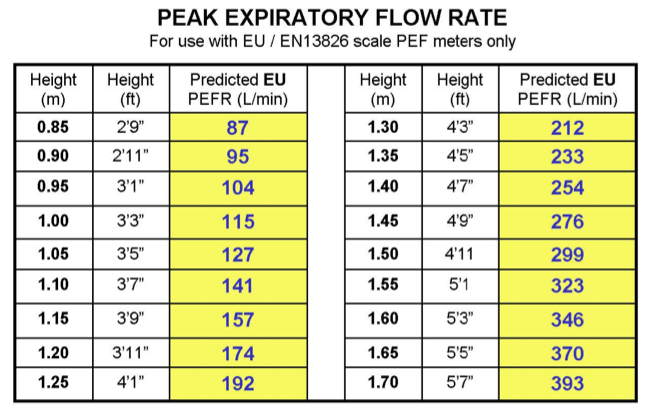

Table 1.1 Peak expiratory flow normal values in children. Normal PEF values in children correlate best with height; with increasing age, larger differences occur between the sexes. These predicted values are based on the formulae given in Cotes JE and Leathart GL (1993) Lung Function (4e) Blackwell, Oxford, adapted for EU scale

MiniWright peak flow meters by Clement Clarke

Adults and children over 5 years with PEF greater than 75% of expected value:

give usual inhaled bronchodilator. Check PEF afterwards check inhaler technique consider commencing inhaled beclometasone, or ensure that the patient is taking an adequate dose of inhaled

corticosteroid .

asthma specialists may consider adding a longacting betaagonist (LABA)

consider prescribing peak flow meter if patient does not aIready have one

recommend recording the results on a chart

advise the patient to seek further help from the most appropriate NHS agency if the asthma worsens despite the increase in treatment

follow up in asthma clinic after 12 weeks for review of longterm treatment

Children 5 years and younger with mild symptoms

try usual bronchodilator or, if uncooperative, nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg

observe, assess effect, listen to the chest again

consider commencing inhaled beclometasone, or ensure that the patient is taking an adequate dose of inhaled corticosteroid

continue inhaled bronchodilator, but ensure adequate technique

if inadequate, consider changing the inhaler delivery system, e.g. using an Aerochamber or changing to a breathactuated device

advise parents to seek further medical help if the asthma worsens: child more distressed, breathing faster, wheezing more, recession

review in asthma clinic after 1-7 days depending on severity and parental confidence in dealing with asthma

Stridor

| Croup | Epiglottitis |

|---|---|

| 6 months-3 years | 2-7 year |

| Parainfluenza virus | Haemophilus influenzae |

| Often mild or no fever | > 38C |

| May not look too ill | looks ill, toxic, tachycardic |

| Sometimes can eat/drink | drooling saliva |

| Parainfluenza virus | Child prefers sitting upright |

| Often preceded by a prodromal coryzal illness in hours | Rapid course progressing in hourssore throat |

| loud | muffled quieter than croup(unfinished) |

NEVER examine the throat of a child with stridor – if epiglottitis, may precipitate complete airways obstruction

3. Assess the degree of respiratory obstruction. Signs of severity are:

(i) Cyanosis-an emergency

(ii) Generalized restlessness or drowsiness

(iii) Tachycardia

(iv) Intercostal recession and accessory muscle respiration

(v) Continuous stridor

4. Refer urgently a child with signs of obstruction epiglottitis is one instance where the GP should accompany the child to Casualty.

Inhaled foreign body may cause immediate obstruction with acute sudden onset stridor with no prior illness necessitating an emergency tracheostomy -make sure you know how to do one

Treatment

1. Treatment of croup is steam inhalation, sitting the child in a bathroom full of steam or boiling a kettle in the bedroom. Instruct the parents when to call for a revisit if the child’s condition deteriorates – viral croup itself can cause sufficient respiratory obstruction to merit referral

Rx oral dexamethasone

2. Admit all cases where there is any suspicion of epiglottitis as an emergency

3 See / visit all children with stridor

| Croup score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscious level | normal 0 | disoriented 5 | ||

| Cyanosis | none 0 | c agitation 4 | at rest 5 | |

| Stridor | none 0 | c agitation 1 | at rest 2 | |

| Air Entry | normal 0 | decreased 1 | marked 2 | |

| Retraction | none 0 | mild 1 | mod 2 | severe 3 |

| Total Score Less than 4 mild 4-6 moderate 7 or more Severe mdcalc croup score NCEMI Croup Score |

||||

Pneumonia (paeds)

Tachycardia and low oxygen saturations are the best predictors of pneumonia in children ADC 2011

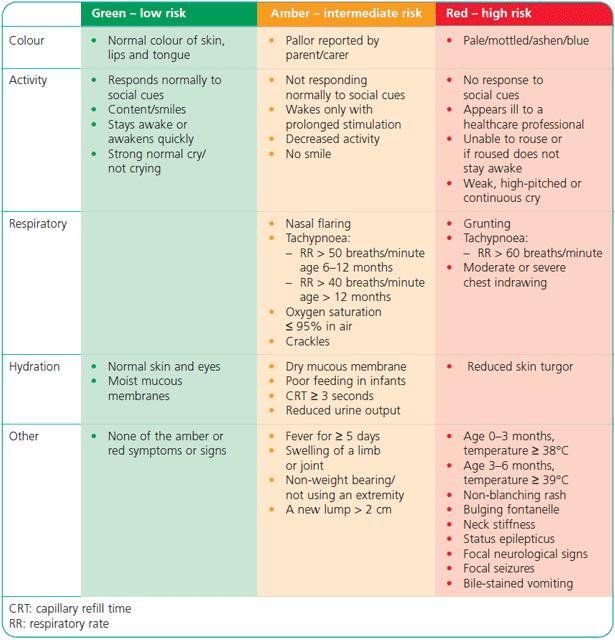

Fever in children NICE traffic lights

NICE CG47 Feverish illness in children May 2007

Ill and Feverish Child Patient UK

Measure and record

Temperature

Heart rate

Respiratory rate

Capillary refill time

Assess for signs of dehydration

Prolonged capillary refill time

Abnormal skin turgor

Abnormal respiratory pattern

Weak pulse

Cool extremities

Febrile convulsions

Around 3% of children between the age of 6 months and 5 years will have at least one convulsion triggered by fever rather than any underlying neurological pathology. Convulsions usually occur at the beginning of the febrile illness and are more likely if the temperature rise is rapid. Fits, which

are mainly generalised tonicclonic, usually last no longer than 20 minutes and are selflimiting with complete recovery within an hour.

Underlying causes

Viral infection (eg upper respiratory tract infection, nonspecific viral illness, roseola, chickenpox etc), otitis media and tonsillitis are the underlying cause of 8590% of presentations. Other possible causes include urinary tract infection, gastroenteritis, lower respiratory tract infection, meningitis, and immunisation.

Management

If the parent or carer telephones, advise them to keep the child lying on his or her side in order to prevent inhalation of vomit.

If the fit lasts longer than 10 minutes give diazepam, preferably as a rectal solution

1 month2 years Diazepam rectal solution 5 mg

212 years 510mg

If the fit is not controlled in 5 minutes, repeat the dose of diazepam. If a child receives multiple doses of diazepam, monitor for respiratory depression.

As soon as is feasible attempt to lower core body temperature

Assessment

The following issues need to be addressed as soon as possible:

What is the likely cause of the fever? It is particularly important to check for the possibility of acute bacterial meningitis, UTI or septicaemia.

Does the febrile illness require treatment in its own right?

Could the fit be the result of some other condition requiring urgent treatment such as hypoglycaemia (check BM), drug overdose, encephalitis or head injury?

Does the child have neurological impairment or developmental delay?

Referral advice

A child should be transferred immediately (????) to hospital if:

? fits are uncontrolled despite 2 doses of diazepam

? breathing/airway is compromised.

A child should be transferred to hospital urgently (???) in any of the following cases. If:

? it is the first fit and they are aged under 18 months

? the fits have atypical features, for example focal seizures

? the fit has lasted longer than 20 minutes

? there is incomplete recovery within one hour

? meningitis is suspected or you are not confident it can be excluded

? the fit is symptomatic of some other disorder requiring admission in its own right, for example hypoglycaemia or trauma

? you are uncertain about the cause of the pyrexia

? this is the second or subsequent fit recurring during the same illness

? there is concern over the ability of the parents to manage the child at home.

In general, a child in supportive circumstances who has a single febrile convulsion can be managed at home. Parents should be advised how to

manage seizures in the event of further fits, ie lowering core body temperature, lying the child on his or her side and administering diazepam.

1. Introduction

These occur in around 3% of children between 6m and 5 years and are triggered by a fever rather than any underling neurological illness such as epilepsy. They typically occur at the outset of the fever, particularly when rising rapidly or spiking. They are tonic clonic lasting up to 20m with full recovery within 1hour. 15% of cases will have further seizures within the same illness.

95% of cases are caused by common infections such as viral URTIs and illness, chicken pox, otitis media, and tonsillitis.

Witnessing a child have a seizure can be frightening for a parent, reassurance and education will help alleviate some of the parents concerns.

Red Flag Warnings

Seizure lasting for more than 15 minutes

More than one seizure a day

Focal seizure

Abnormal neurologic status present preceding the seizure (for example, cerebral palsy)

Less than one year old

Positive family history for epilepsy

Immediate Care Considerations

Maintain / protect airway during seizure

Administer oxygen

Protect from injury during seizure

Take measures to cool the child down

Remove excess clothing

Transfer Hospital

Care for Fitting Child:

Do not restrain them or put anything in their mouth

Note the exact time the seizure started and continue to monitor the duration of the seizure

For prolonged or repetitive seizures administer rectal or intravenous anticonvulsant drugs as prescribed, Once the seizure has finished, place the child in the recovery position to prevent a hypotonic tongue from blocking the airway

Febrile seizures are very common in children, occurring in 3% of under 5s.They tend to be generalized, brief (lasting usually less than 5 minutes and typically triggered by viral-like infections of the ear, pharynx, urinary or gastro-intestinal tract. Febrile seizures that are more complex, demonstrating focal signs or may recur within 24 hours are typically triggered by more serious causes like infections of the central nervous system such as meningitis or encephalitis.

Children who present with a febrile seizure and a family history of epilepsy or underlying neurological conditions such as cerebal palsy should be further investigated as the cause of the seizure may not be the fever, as these children are more likely to have recurrent seizures or epilepsy.

The vast majority of children recover completely even if they have more than one febrile seizure.

Carefully observe and record all aspects of the seizure:

How did it start?

Which part of the body was affected first?

Was more than one area of the body affected at one time?

What kind of movements occurred? Did these movements change?

How long did the seizure last?

Check for signs of dehydration or other signs of compromised health:

Prolonged capillary refill time

Abnormal skin turgor

Abnormal respiratory pattern

Weak pulse

Cool extremities

Tepid sponging is not recommended for the treatment of fever.

Children with fever should not be underdressed or over-wrapped.

The use of antipyretic agents should be considered in children with fever who appear distressed or unwell. Antipyretic agents should not routinely be used with the sole aim of reducing body temperature in children with fever who are otherwise well. The views and wishes of parents and carers should be taken into consideration.

Either paracetamol or ibuprofen can be used to reduce temperature in children with fever. It is no longer recommended they are given together

Antipyretic agents do not prevent febrile convulsions and should not be used specifically for this purpose.

Care for Seizing Child:

Gently lower the child to the floor and place on their side if possible

Do not restrain them or put anything in their mouth

A child should not be left unattended whilst having a seizure

Note the exact time the seizure started and continue to monitor the duration of the seizure

Remove any objects in the nearby area that the child may injure themselves

Talk calmly and reassuringly to the child during and after the seizure

For prolonged or repetitive seizues administer rectal anticonvulsant drugs as prescribed, Once the seizure has finished, place the child on their side

An other wise well child over 18m may who has made a full recovery after a first febrile seizure may be managed at home if parents are happy and there are no worrying features.

Burns rule of nines (child)

Thermal Burns: Initial Assessments and Management Tips @ Firerescue.com

Safeguarding children / child protection

MPS Factsheet Safeguarding Children

NICE PH28 Looked-after children and young people Oct 2010

https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/Childrenandfamilies/Page2/DCSF-00305-2010

http://www.corelearningunit.nhs.uk/SignIn.aspx

Paeds approach to the patient

History

Past medical history

Birth history

Immunisations

Developmental history

Feeding/diet

Family history

Drug history

Social history Family and siblings

School

Red-flags

Developmental delay, poor growth/weight gain

Child protection issues, abuse/neglect

Examination

Plot on centile charts: height, weight, head circumference

Alert, responsiveness, hydration

Uncooperative child and anxious parent/grandparent

Wrapping in a blanket

In an emergency, such as cement inside the lids. if necessary wrap the child up in a blanket to prevent struggling, the arms should be separate inside the layers of blanket and. with an assistant steadying the head ‘and body, lay the child supine on a couch or the floor.

It may be difficult to separate the eyelids. and Casualty Departments should have a pair of curved wire lid speculae for this purpose, as well as sterile saline for irrigation by means of an I.V. giving set. or an undine, after liberal instillation of local anaesthetic drops.

While the child is restrained there will be an opportunity to check the cornea for abrasions or foreign bodies; treatment for this may be given immediately. or if necessary deferred in favour of a general anaesthetic later

Tongue depressor trick

Paeds examining the throat

Paeds examining the Ear

Child health surveillance

hacking-medschool/child-health-surveillance-2

Health promotion (inc Immunisation), screening, and early intervention

Newborn

General physical examination with emphasis on heart, eyes and hips.

Administration of vitamin K, BCG and hep B in high-risk babies

5-6 days – Blood spot test for hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria. Sickle cell, cystic fibrosis, MCAD

Newbirth visit 12 days

Assessment of family’s needs plus family given personal child health record and ‘Birth to Five’ guide HV or MW

6-8 weeks Physical examination and administration of first set of immunisations: polio, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, Hib and meningitis C

3 months Second set of immunisations.

4 months Third set of immunisations

12 months Further developmental assessment.

Around 13m MMR immunisation

2-3 years Health visitor performs further developmental assessment

3-5 years MMR, polio, diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough boosters

4-5 years School entry review (SN). Foundation stage profile (teacher) physical, emotional, social creative development language and literacy.

10-14 years Tetanus, BCG vaccination given to those who require it.diphtheria and polio boosters (age 1318 years)

Childhood developmental milestones

4-6 w smiles responsively

6-7 m sits unsupported

9m gets to a sitting position

10m pincer grip

12m 2-3 words

15m walks indpendantly

18m tower of blocks

24m 3 word sentances

30m dry by day

| Developmental Red flags (Palmer & Boeckx notes for MRCGP) | |

|---|---|

| Age (months) | Red Flag |

| 2 | absent smile fails to vocalise |

| 4 | persistant fist clenching no laugh |

| 6 | fails to localise voice head lag |

| 9 | fails to sit unsupported fails to say mama or dada non-specifically |

| 12 | fails to stand alone for 2 seconds |

| 15 | fails to walk alone |

| 18 | fewer than 20 words no scribble |

| 24 | fails to kick a ball |

| Developmental Milestones to 6m | |

|---|---|

| 1 m | Lifts head when lying on tummy Responds to sound Stares at faces Follows objects briefly with eyes Vocalizes: oohs and aahs Can see black-and-white patterns Smiles, laughs Holds head at 45-degree angle |

| 2 m | Vocalizes: gurgles and coos Follows objects across field of vision Notices his hands Holds head up for short periods Smiles, laughs Holds head at 45-degree angle Makes smoother movements Holds head steady Can bear weight on legs Lifts head and shoulders when lying on tummy (mini-pushup) |

| 3 m | Recognizes your face and scent Holds head steady Visually tracks moving objects Squeals, gurgles, coos Blows bubbles Recognizes your voice Does mini-pushup Rolls over, from tummy to back Turns toward loud sounds Can bring hands together, bats at toys |

| 4 m | Smiles, laughs Can bear weight on legs Coos when you talk to him Can grasp a toy Rolls over, from tummy to back Imitates sounds: “baba,” “dada” Cuts first tooth May be ready for solid foods |

| 5 m | Distinguishes between bold colors Plays with his hands and feet Recognizes own name Turns toward new sounds Rolls over in both directions Sits momentarily without support Mouths objects Separation anxiety may begin |

| 6 m | Turns toward sounds and voices Imitates sounds Rolls over in both directions Is ready for solid foods Sits without support Mouths objects Passes objects from hand to hand Lunges forward or starts crawling Jabbers or combines syllables Drags objects toward himself |

Neonatal Examination / Newborn Babycheck

Record details of pregnancy & delivery

FH. Heredity diseaese and health of siblings.

APGAR at 1 min and 5 min.

Skull & Spine

Limbs & Gestation.

Birthweight.

Placenta. Cord Vessels.

Head Circ

Ht

Wt

Temp

Pulse

Resps

Facies

Skull

Palate

Fontanelles

Eyes Red Reflex

Ears

Lungs

Heart Sounds

Femoral pulses

Abdomen

Genitalia

Anus

Skeletal Symmetry

Hips

Skin

Muscle Tone

Reflexes

6 week baby check

Start by asking some open questions to elicit any concerns about development/feeding/sleeping

Specifically ask about social smile, are they moving their eyes to follow things and startling to loud noises?

Talk through what you’re doing and be very reassuring about all the normal findings, try not to give too much detail which might be alarming (“I’m just checking for congenital heart disease” may not go down well!)

Explain about the hip check (“I’m going to check their hips now, sometimes they don’t like this bit very much but it doesn’t hurt them so try and bear with me” or similar)

This is a good opportunity to observe the parent and baby interacting, it’s usually mum who brings them so be aware of PND and ask some screening/open questions to check this out.

Examination

It’s a systematic check but you can do the component parts in any order, as with all paediatric examinations auscultate the heart while they’re settled, before undressing if necessary.

Wash Hands

Observe:

Alertness/dysmorphia/tone when handled by parent/smile/response to noise.

Ears and palms (? dysmorphia/palmar crease)

Check:

Weight, length, head circumference

Heart sounds (ASAP!)

Fontanelle

Eyes red reflex/co-ordinated movement to follow things

Abdomen palpate, check the umbilicus is ok

Head control/tone – Head lag still present but can hold level momentarily in ventral suspension Prone may just transiently lift head off the couch

Mora reflex should be symmetrical

Hips- Barlow=test for dislocatable hip

Ortolani=test for dislocated hip

Nappy off be quick!

Femoral pulses, testis, genitalia (hypospadias)

Nappy back on

Spine dimples/hairy patches and ventral suspension (observing tone again)

wash hands again and check palate

Motor

Hearing does baby respond/ quieten to sound?

Vision eyes can fixate and follow through 90 degrees from midline (when supine)

Socialising baby smiling?

Document findings in the red book and make an appropriate follow up plan if there are any areas you have been unable to assess/findings you are unsure of/definite abnormal findings which require referral.

Reassure parent/carer if all is well and offer further review if they have any concerns.

Kate Eve Bradford VTS

Developmental dysplasia of the hip CDH

6Fs

foetal actors (multiple pregnancies, oligohydramnos, caesarean delivery)

firstborn

female

family history

floppy/hypotonic

feet first (breech)

postural deformities of the feet

asymmetrical leg creases

Barlows test for dislocataBle hip. Hip flexed to 90 degrees and addicted.femoral head is then pushed posteriorly while Inge ally rotating – a dislocataBle hip will clunk as it slips over the rim of the acetabulum.

Ortolanis test for hip that is already dislocated the hips and knees are flexed with examiners middle finger over the greater trochanter and thumb along the medial femur. Pull the hip gently forward while abducting

Barlow’s Backwards

Ortilani’s Outwards

(mnemonics for medical students Khan)

DDH Paediatric Orthopaedics.com

Neonatal screening

newbornbloodspot.screening.nhs.uk

Pulse Oximetry Screening for CHD in neonates Lancet Aug 2011

MCADD

medium chain acylcoenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency

Rare, life-threatening autosomal recessive condition.

Neonatal jaundice

NICE CG98 Neonatal Jaundice May 10

British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition

Causes for jaundice in infants

physiological jaundice

breast milk jaundice

liver disease

haemolysis

infection

hypothyroidism

Urine and stool colour

urine normally colourless – persistently yellow urine which stains the nappy can be a sign of liver disease

stools normally green or yellow – persistently pale or clay coloured stools may indicate liver disease

If the stools and urine in a jaundiced baby are abnormal in colour, the baby should be referred to paeds immediately

First visit of midwife and/or health visitor

Every baby should be checked for jaundice by looking at the sclera of the eyes

The presence of jaundice in an infant should always be recorded when transferring a baby from the midwife to the health visitor

If the baby is jaundiced, however mild, stools and urine should be checked and seen by either the health visitor and/or midwife

Prolonged jaundice

beyond two weeks in term babies and three weeks in preterm babies (whether or not the baby has pale stools)

if the baby unwell and/or not progressing normally then refer paeds

Assessment

feeding history including whether breast or bottlefed

weight

document stool and urine colour

inform parents of reason for blood tests

Blood tests

serum total bilirubin

split bilirubin – conjugated (direct) bilirubin level and the unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin levels

– in all babies with prolonged jaundice be given a split bilirubin test

– in breastfed babies (an unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia)

Causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia

prolonged physiological jaundice

breast milk jaundice

Crigler Najjar Syndrome

haemolysis (red cell breakdown)

If the conjugated bilirubin is >20% of the total bilirubin, the baby should be referred for immediate investigation by a paediatrician

If the conjugated bilirubin is <20% of the total and the total bilirubin is less than 200 micromoles/l, the parent(s)/guardian(s) should be reassured and weekly serum bilirubin levels checked until it returns to normal

Where the total bilirubin is very high (> 200 micromoles/l) and the conjugated fraction is <20%, healthcare professionals are advised to contact a paediatrician.

Other tests

LFTs

albumin

aspartate and alanine transaminases (AST, ALT)

alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT)

blood glucose

coagulation tests

prothrombin time (PT)

partial thrombin time (PPT)

Coagulation may be prolonged secondary to vitamin K deficiency, particularly in breastfed babies not given vitamin K at birth. All babies with suspected liver disease must be given vitamin K orally if INR is normal or intravenous/intramuscular if abnormal

Liver disease in infants

Neonatal rashes

pedclerk.bsd.uchicago.edu Neonatal Skin

stephen-a-christensen.suite101.com/benign skin rashes in infants

Birthmarks in newborns and children

newborns.stanford.edu/Port Wine

newborns.stanford.edu/Slate Grey

Nappy rash

pee-sac

psoriasis

eczema

excoriation – diarrhoea acid stools disaccharide intolerance

seborrhoeic dermatitis

ammonical dermatitis

candidiasis

Red, shiny, wet-looking rash of the skin in the nappy area of babies. Caused by prolonged exposure to urine and faeces. Usually mild and can be treated with a simple skincare:

frequent nappy changes

leaving nappies off for part of the day

and zinc and castor oil cream as a barrier.

anti-candida treatment

- Differential diagnosis

Primary bacterial infections

Impetigo

Perianal streptococcal dermatitis

Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis

Atopic eczema

Eczema herpeticum

Psoriasis.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Rare causes of nappy rash

Zinc deficiency may present with nappy rash that fails to respond to normal treatments. It is more common in premature infants and is associated with dermatitis around the mouth and erosive lesions of the nails and palmar creases.

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis commonly presents in the third month of life with persistent intertrigo. Initially small, yellow papules develop which become confluent and subsequently ulcerate.

Bacterial infection — marked redness with exudate, and vesicular and pustular lesions.

Candidal infection — sharply marginated redness around the perianal skin, which may involve the perineum. Confluent zones of papules and pustules involving the skin creases. Satellite lesions are characteristic of candida infection.

Check for oral candidiasis — if present, it increases the likelihood of nappy rash with candidal colonization

Treatments

The area should be cleaned regularly with warm water.

Aqueous cream or similar emollients can be used as a soap substitute.

Soap, talcum powder or perfumed nappy wipes should not be used.

Nappies should be changed as soon as possible after wetting or soiling.

The nappy should remain off for as long as possible each day and allow the baby’s bottom to air dry as much as possible.

Make sure that the baby’s bottom is completely dry before putting on a new nappy.

A water repellent emollient or barrier preparation should be used with each nappy change; a pharmacist can advise about suitable nappy rash creams.

Apply/administer antibiotic medicine as ordered

If disposable nappies are used, choose those that are made with materials that lock wetness inside the nappy and away from the skin.

Advice to reduce exposure to irritants:

Leave nappies off for as long as possible

Consider using nappies with a high absorbency factor

Clean and change the child as soon as possible after wetting or soiling

Use water, or fragrance and alcohol-free baby wipes

Avoid vigorous rubbing after cleaning

Do not use soap, bubble bath, or lotions

Avoid excessive bathing (such as more than twice a day) which can be drying to the skin

Nappy rash Rx

Barrier preparations

Age under 6 years

Zinc oxide ointment BP

Zinc ointment

Apply to the affected area after each nappy change.

Supply 100 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £0.88

Licensed use: yes

Patient information: Change nappies frequently and whenever possible leave the affected area exposed to the air.

Zinc and castor oil ointment BP (contains peanut oil)

Zinc and Castor oil ointment

Apply to the affected area after each nappy change.

Supply 100 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £0.57

Licensed use: yes

Patient information: Change nappies frequently and whenever possible leave the affected area exposed to the air. Tell your doctor if you or your baby are allergic to nuts.

Titanium ointment (Metanium®)

Titanium ointment

Apply to the affected area after each nappy change.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £2.01

Licensed use: yes

Patient information: Change nappies frequently and whenever possible leave the affected area exposed to the air.

White soft paraffin BP

White soft paraffin solid

Apply to the affected area after each nappy change.

Supply 500 grams.

Age: under 6 years

Licensed use: no – off-label indication

Patient information: Change nappies frequently and whenever possible leave the affected area exposed to the air.

Dexpanthenol 5% ointment (Bepanthen®)

Dexpanthenol 5% ointment

Apply to the affected area after each nappy change.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £2.1

OTC cost: £3.22

Licensed use: no

Topical imidazole (nappy rash)

Age under 6 years

Clotrimazole 1% cream: apply two to three times a day

Clotrimazole 1% cream

Apply to the affected area 2 to 3 times a day. Continue for at least 2 weeks after the affected area has healed.

Supply 20 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £1.92

OTC cost: £3.38

Licensed use: yes

Econazole 1% cream: apply twice a day

Econazole 1% cream

Apply to the affected area twice a day. Continue for 2 to 3 days after the affected area has healed.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £2.75

OTC cost: £4.85

Licensed use: yes

Ketoconazole 2% cream: apply once or twice a day

Ketoconazole 2% cream

Apply to the affected area(s) once or twice a day. Continue for a few days after the affected area has healed.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £3.54

Licensed use: yes

Miconazole 2% cream: apply twice a day

Miconazole 2% cream

Apply to the affected area twice a day. Continue for 10 days after the affected area has healed.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £1.93

Licensed use: yes

Sulconazole 1% cream: apply once or twice a day

Sulconazole 1% cream

Apply to the affected area once or twice a day. Continue for at least 2 weeks after the affected area has healed.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: under 6 years

NHS cost: £3.9

OTC cost: £6.87

Licensed use: yes

Topical corticosteroid

Age from 1 month to 6 years

Hydrocortisone 0.5% cream

Hydrocortisone 0.5% cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 15 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.65

Licensed use: yes

Hydrocortisone 1% cream

Hydrocortisone 1% cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 15 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.19

Licensed use: yes

Topical anticandidal + hydrocortisone

Age from 1 month to 6 years

Clotrimazole 1% + hydrocortisone 1% cream

Clotrimazole 1% / Hydrocortisone 1% cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.42

Licensed use: yes

Miconazole 2% + hydrocortisone 1% cream

Miconazole 2% / Hydrocortisone 1% cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.08

Licensed use: yes

Nystaform HC cream (contains nystatin and hydrocortisone 0.5%)

Nystaform HC cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.66

Licensed use: yes

Patient information: Wash hands after applying cream. This cream only needs to be applied thinly. Measure ONE ‘fingertip unit’ by squeezing the cream in a line from the tip of an adult’s index finger to the first crease in the finger. ONE fingertip unit is enough to cover an area that is twice the size of a flat adult hand.

Timodine cream (contains nystatin + hydrocortisone 0.5%)

Timodine cream

Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice a day. If there is no improvement after 7 days return to your doctor; if there is an improvement, continue using this cream for up to 14 days.

Supply 30 grams.

Age: from 1 month to 6 years

NHS cost: £2.38

Licensed use: yes

Oral flucloxacillin (nappy rash)

Age under 1 month

Flucloxacillin oral solution: neonate under 7 days

Flucloxacillin 125mg/5ml oral solution

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 25mg per kg bodyweight TWICE a day for 7 days.

Supply 100 ml.

Age: under 1 month

NHS cost: £2.94

Licensed use: yes

Flucloxacillin oral solution: neonate 7-20 days

Flucloxacillin 125mg/5ml oral solution

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 25mg per kg bodyweight THREE times a day for 7 days.

Supply 100 ml.

Age: under 1 month

NHS cost: £2.94

Licensed use: yes

Flucloxacillin oral solution: neonate 21-28 days

Flucloxacillin 125mg/5ml oral solution

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 25mg per kg bodyweight FOUR times a day for 7 days.

Supply 100 ml.

Age: under 1 month

NHS cost: £2.94

Licensed use: yes

Age from 1 month to 1 year 11 months

Flucloxacillin oral solution: 62.5mg four times a day

Flucloxacillin 125mg/5ml oral solution

Take 2.5ml four times a day for 7 days.

Supply 100 ml.

Age: from 1 month to 1 year 11 months

NHS cost: £5.03

Licensed use: yes

Age from 2 to 6 years

Flucloxacillin oral solution: 125mg four times a day

Flucloxacillin 125mg/5ml oral solution

Take one 5ml spoonful four times a day for 7 days.

Supply 200 ml.

Age: from 2 years to 6 years

NHS cost: £10.06

Licensed use: yes

Penicillin allergy: oral erythromycin or clarithromycin (nappy rash)

Age under 1 month

Erythromycin s/f suspension: 12.5mg/kg four times a day

Erythromycin ethyl succinate 125mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 12.5mg per kg bodyweight FOUR times a day for 7 days.

Supply 100 ml.

Age: under 1 month

NHS cost: £1.71

Licensed use: yes

Clarithromycin suspension: child less than 1 month old

Clarithromycin 125mg/5ml oral suspension

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 7.5mg per kg bodyweight TWICE a day for 7 days.

Supply 70 ml.

Age: under 1 month

NHS cost: £5.58

Licensed use: yes

Age from 1 month to 1 year 11 months

Erythromycin s/f suspension: 125mg four times a day

Erythromycin ethyl succinate 125mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free

Take one 5ml spoonful four times a day for 7 days.

Supply 200 ml.

Age: from 1 month to 1 year 11 months

NHS cost: £5.46

Licensed use: yes

Age from 1 month to 3 years

Clarithromycin suspension: child weighs 7.9kg or less

Clarithromycin 125mg/5ml oral suspension

*WEIGHT REQUIRED* Give 7.5mg per kg bodyweight TWICE a day for 7 days.

Supply 70 ml.

Age: from 1 month to 3 years

NHS cost: £5.58

Licensed use: yes

Age from 1 year to 2 years 11 months

Clarithromycin suspension: child weighs 8kg to 11.9kg

Clarithromycin 125mg/5ml oral suspension

Take 2.5ml twice a day for 7 days.

Supply 70 ml.

Age: from 1 year to 2 years 11 months

NHS cost: £5.58

Licensed use: yes

Age from 2 to 6 years

Erythromycin s/f suspension: 250mg four times a day

Erythromycin ethyl succinate 250mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free

Take one 5ml spoonful four times a day for 7 days.

Supply 200 ml.

Age: from 2 years to 6 years

NHS cost: £5.42

Licensed use: yes

Age from 3 to 6 years

Clarithromycin suspension: child weighs 12kg to 19.9kg

Clarithromycin 125mg/5ml oral suspension

Take one 5ml spoonful twice a day for 7 days.

Supply 70 ml.

Age: from 3 years to 6 years

NHS cost: £5.58

Licensed use: yes

Perianal streptococcal dermatitis

Perianal Streptococcal Dermatitis BMJ

Perianal Streptococcal Dermatitis AAFP Jan 2000

Perianal streptococcal dermatitis Dermnet.nz

Bright red, sharply demarcated rash that is commonly misdiagnosed and treated as a fungal infection.

It occurs most commonly in children 3–4 years of age. It remains unresponsive to treatment with topical steroids and antifungal creams.

Perianal pain and itching are common and blood-streaked stools occur in up to a third of cases.

Cradle cap seborrhoeic dermatitis

hacking-medschool/seborrhoeic-dermatitis

Cradle Cap @ Web MD

Greasy yellow scale + erythema on the scalp and forehead. Nappy areas and limb flexures may also be affected.

Mainly infants under 3 months of age – usually disappears by 12m.

Caused by a disorder in the production of sebum from glands in the skin of the scalp eyebrows, ears, and nasolabial folds.

Unlike atopic eczema, not itchy or painful.

Not contagious nor an indicator of poor care.

If severe or refractory swabbing may help exclude secondary bacterial infection or thrush

Will generally clear on its own with mild emollient therapy such as an emollient bath daily and a light emollient cream +/- antifungal if indicated.

Thick crusts on a baby’s scalp can be removed by soaking them with baby oil for 20-30 minutes every day.

The hairy area of the scalp is then washed with zinc pyrithione shampoo.

Do not to remove adherent scales by picking – as this may result in hair loss or introduce infection

However baby oil can be applied to the scalp and gently massaged in to loosen the scales and encourage them to separate The oil can be left in for 30 minutes to overnight, depending on the severity of the cradle cap

A mild infant shampoo can be used to remove the oil

A soft baby brush can then be used to gently remove the loosened scales

Infant feeding

Feeding problems

mayoclinic.com feeding problems

nationwide childrens.org feeding disorders

Breast feeding (paeds)

Breast feeding babycentre.co.uk

Bottle Feeding

Daily Requirements 150mls/kg in 4-6 feeds (1oz = 30 mls)

dh.gov.uk Guide to bottle feeding

Types of milk

Vitamins for kids

weight loss resources.co.uk children/nutrition/calorie needs

Nice PH 11 Maternal and child nutrition Mar 2008

Infantile colic

A systematic approach to the differential diagnosis and management of infant colic

Working Party – Marks, Archbold, Augstburger, Clayton, Lord, Kanabar, Majid & Morgan

INFANTILE COLIC

Usually beginning ill the first few weeks of life resolving by 4 months

Attacks tend to occur in the early everling when, without any clear reason, the child begins to cry inconsolably, bends the knees and pulls the legs up towards the abdomen, seems to be in pain, and may pass wind.

trial of treatment

– with hypoallergenic formula 2 weeks

– for reflux oesophagitis

Excessive crying vs normal crying- rule of threes

crying/whimpering for at least 3 hours a day

at least 3 days a week,

for a minimum of 3 weeks

By 4 months, most infants’ crying has dropped to a normal level.

GORD infants

Gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants DTB 2009, Vol 47 (12)

childrenshospital.org aug 07/reflux in infants

Weaning

Lactose intolerance / cows milk allergy

Lactose Intolerance NHS choices

cows milk intolerance expert babycentre.co.uk

Primary: due to a physiological decline in lactase concentrations at the time of weaning

Secondary: commonly due to temporary injury to the intestinal mucosa due to infection

Reduced intestinal lactase results in malabsorption of lactose, which is then metabolised by colonic bacteria to produce gas and fatty acids, abdo cramps, bloating, diarrhoea and flatulence

Failure to thrive

Inadequate wt gain and linear growth in infancy

Short stature and growth disorders

- RETARD HEIGHT

Rickets

Endocrine (cretinism, hypopituitarism, Cushing’s)

Turner syndrome

Achondroplasia

Respiratory (suppurative lung disease)

Down syndrome

Hereditary

Environmental (post-radiation, postinfectious)

IUGR

GI (malabsorption)

Heart (congenital heart disease)

Tilted back (scoliosis)

Growth disorders Health Direct au

Crying baby

A babies only way of communicating and usually an expression of unmet need – hunger thirst discomfort or need for more physical contact.

If feeding weight gain and overall health OK parents can be reassured wil settle at 3-4 months.

Hunger

Prem babies may need larger volumes at 2-3 hours

Demand feeding generally preferable to 4 hourly

Sleeping through the night occurs roughly when bay eaches 5kg

Thirst

Increased in pyrexia or hot weather. Offer fluids between feeds if baby remains unsettled.

Colic

Evenings 5-10pm till 3-4m. Baby cries and draws up legs

Wind

Excessive air swallowing may be due to blocked teat or excesive milk secretion in first few minutes.

Try expressing some milk before starting feeding and nursing upright after feeding.

Underfeeding

Overfeeding

Colics

Sleep problems in babies

Sleep problems in childhood

Incidence

about 10% of pre-school children are considered to be poor sleepers by their parents

Aetiology:

Possible causes of childhood sleep disturbance include:

a child may have become “trained to stay awake”

separation anxiety

depression

nightmares

child wakes terrified; remembers the dream

age 8-10 years

night terrrors

child half-wakes terrified; still dreaming; cannot remember the dream when he wakes in the morning

sleep walking

very rare condition

occurs generally between 11-14 years of age

child wakes half-awake and calm; child had no memory of the event on waking the following morning

childhood illness

Management:

A common cause of sleep disturbance in a child is that the child has been “trained to stay awake”. A child may have been ‘rewarded’ for waking or crying at night e.g. with a cuddle, drink or being taken into his parents’ bed.

Methods that might help with “training to sleep” include:

attending to the crying child but limiting the attention to excluding physical problems such as a wet, sodden nappy

not attending to a child as soon as he wakes but instead waiting until he cries. Children will often wake transiently at night

gradually increasing the time a child is left to cry before attending

not providing ‘rewards’ for waking e.g. cuddles, drinks

use of sedative medication (e.g. a sedative antihistamine such as Vallergan (R)) is a last resort used on a short-term basis. Parents should be encouraged to modify their own pattern behaviour so as to encourage good sleeping habits when the sedative medication is withdrawn. Specialist review may be required if the problem persists melatonin may be indicated in the management of childhood sleep disorders

Advice from the book Toddler Taming by Dr Christopher Green

Children with poor sleep patterns have an immense impact on the whole family as well as the child themselves and up to 1/3 of children between the ages of 1-4 wake at least once every night.

Sedatives can be used as a short-term measure, but they don’t solve the problem in the long run and often they can have the side-effects of making the child drowsy the following day or have the paradoxical effect of making them hyperactive. Possible advice that you could give to a parent with a child who has sleep problem to try to train and modify their sleep patters are:-

Follow a regular routine leading up to bedtime and put the child to bed at a consistent time.

Calm them down before bedtime. i.e. don’t wind them up and get them excited such as fighting, chasing, running, playing wild games with them. Instead ease them down by giving them bath, talking to them quietly and gently, tucking them in bed, giving them a cuddle, reading a bed time story.

Once it is time to leave do it decisively, say goodnight and mean it. Don’t rise to any request that have no purpose except to procrastinate e.g. needing a drink, wanting to go to the toilet, for you to lie down with them etc.

If the child gets out of bed, you must return them at once. Be firm, take charge, do it without any questions or fuss. Keep repeating this process each time the child reappears and make sure both parents do the same to show a united front.

Alternatively you can choose to sit quietly at the bedside of the child until they start to fall asleep. Your there to offer your presence, not act as bedtime entertainment. If they lie quietly then you stay, but once they start to climb out of bed or question then leave decisively.

Children who get up in the middle of the night and cry, often do it for attention. It has been shown that in children who wake in the middle of the night where comfort is not readily available, generally decide it is easier to settle themselves back to sleep without making much of a fuss. Dr Green in his book suggests the controlled crying technique as follows:

Decide on a length of time to leave the child crying for before you attend to them and the length of time depends on how tolerant the parent is and how genuinely upset the child becomes. The aim is to not let them get too hysterical or afraid. (on average 5mins, 10mins if tough and 2mins if they’re feeling weak).

After the allotted time has passed then go to the toddler room, lift, cuddle and comfort until the loud upset crying turns to sobs and eventually sniffles. This is the sign to then put them down and walk away. The child may be quite taken aback that the parents has dared to leave and likely will immediately start to cry again in protest. This time leave the child to cry 2mins longer than the last time and repeat the same procedure and continue adding on 2mins and increasing the time you take attend to the child. Follow the same routine each night and after a couple of days to weeks , they should soon notice a different. However, you have to encourage the parents to persevere and be strong in their resolve.

In this method the child knows that the comfort is always there and they are not left to cry for hours in fear alone, but they soon learn that it is not readily available and you won’t rush to their every whimper and demand and that it isn’t worth all the effort.

Abdo pain kids

http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Recurrent-Abdominal-Pain-in-Children.htm

Constipation

NICE CG99 2010 Constipation in children and young people

Normal frequency varies 3x day -1 every 3 days

Quantity and frequency of defaecation depend first of all on the

quality and quantity of food and fluid consumed. Food with little

plant-based fibre provides only minimal undigested matter in the

colon, which means the capacity of the intestinal contents to absorb

water is very small. This results in faeces consisting primarily of dead

bacteria, so that, even if enough water is consumed, a small, dry mass

is produced. Because this mass does not expand in the colon, there

are minimal propulsive contractions, and transit is slow.

Normally, the faecal material is retained in the rectum and colon until

sufficient stimuli are present to relax the upper anal sphincter. As

the faeces enter the anal canal, there is an urge to defaecate. In

addition, the external anal sphincter contracts to prevent undesired

evacuation. Defaecation is only possible after this sphincter has been

relaxed consciously.

This normal process can become disrupted due to anatomical,

functional and psychological factors. In childhood, 90% of

constipation is functional. Organic causes are usually discovered

before the child’s third year. The various aetiologies of constipation

vary according to the child’s age.

In infants up to 5 months old, constipation is usually related to the composition of the milk. Breast-feeding can result in relatively

infrequent, hard faeces. Incorrectly prepared bottle formula (too

much milk powder per unit of water) can also lead to constipation,

and small anal fissures may aggravate the situation.

Rare causes – Hirschsprung’s disease and meconium ileus.

Between 2 and 5 months of age a baby may simply have difficulty

evacuating the faeces (its face turns red). The faeces are visible at the

anal opening, but are not easily passed. Incomplete coordination of

the various motor reflexes seems to be the cause. This ‘problem’

disappears spontaneously.

In children of pre-school age, constipation is usually caused by

emotional or behavioural factors, although changes in diet and

potty training may be relevant. Chronic constipation in children

under 2 years of age, a constantly bloated abdomen and an empty

rectum during a digital rectal examination, strongly suggest the

diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease. Early diabetes, lead intoxication,

hypercalcaemia and various renal and metabolic disorders can also

be the cause.

In school-age children, constipation usually presents as stomach

ache. Only on inquiry is slow, infrequent defaecation reported.

Peculiar dietary patterns, sometimes involving the entire family,

are often found. Acute painful constipation may also be related to

irritable bowel syndrome (lBS). Extreme cases of faecal soiling and

encopresis, both usually the result of long-term overfilling of the

colon and rectum, require a great deal of attention. The assistance

of a paediatrician and/or a child psychologist may be valuable.

In puberty, most constipation results from an imbalanced diet.

Anorexia nervosa can also playa role at this age: the resistance to

food and the desire to lose weight can lead to minimal food intake,

constipation and laxative use.

Some children may experience pain during defaecation, and the fear of this can cause them to suppress the mge to defaecate, thereby

aggravating the problem. In severe chronic constipation, symptoms may include a lack of

appetite and general malaise. Recurring stomach aches, urinary tract infections or ‘paradoxical’

diarrhoea can also be symptoms of constipation.

TREATMENT

For infants, provide dietary advice: if bottle-feeding, add more water, possibly with a few teaspoons of orange juice or juice from

soaked prunes an alternative is a lactose-rich milk formula; in those on solids, vegetables, h’uit (not too finely chopped) and

brown bread should be encouraged. Children who consume a lot of milk and juice often have less appetite for solid foods with the

necessary fibre.

Bristol stool chart

Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time Lewis and Heaton 1997

Encoporesis and soiling

Encoporesis and Soiling PubMed 2009

Encoporesis.com Commercial Site

Gastroenteritis in infants

| Management of feeding during rehydration and maintenance phases | |

|---|---|

| Breast Fed | Continue breast-feeding throughout rehydration and maintenance phase |

| Formula fed | Restart feeding at full strength as soon as rehydration is complete (ideally after 4 hours) |

| Weaned children | Give the child normal fluids and solids after rehydration. Avoid fatty foods or foods high in simple sugar |

Toddlers Diarrhoea PUK

Lactose intolerance PUK

E Coli 157 Common and potentially serious cause of admission with diarrhoea

Rotavirus causes one third of all hospital admissions for diarrhoea and leads to about 600 000

deaths per year / 6% ofdeaths in the under fives. In the UK, 1 in 40 children are admitted to hospital

for rotavirus infection in their first 5 years.

Rotavirus vaccination

Diarrhoea and Vomitting (babies/children)

Gastroenteritis in kids

NICE CG84 Diarrhoea and vomiting in children under 5 Apr 2009

1. Assessment of the state of hydration examine the child to exclude other diagnoses and to provide some indication of the state of hydration.

Remember that a baby who is seriously dehydrated may continue to feed well, so feeding itself should not be used as an indication of well being. Signs of dehydration are not usually present until there is a weight loss of about 3%.

Minimal

(Less than 3%)

MildModerate (3-8%)

Severe

(9% or more)

Decreased skin turgo

Tachycardia

Decreased urine outpu

Mouth dryness

Eye signs (sunkenness)

Level of consciousness

Clinical features

r +/ +++

– +/ + + +

t + + + + + +

+/(moist) + (dry) +++ (very dry)

(normal) + +(sunken) + + + (very sunken & dry)

(well, alert) +/(restless, irritable) + + +(lethargic, unconscious,floppy)

2. Rehydration For those with 3% or more dehydration give oral rehydration solution (eg dioralyte or electrolade) over 4 hours.

Mild to moderate dehydration (3-8% weight loss) 30-80mL/kg in 4 hours

Severe dehydration (weight loss of 9% or more) Refer to hospital immediately (????)

Give fluid little and often. If the child is vomiting, reduce the volume and give the fluid more frequently.

3. Maintenance Once rehydration has been achieved ensure that the child receives their normal fluid requirements. These can be calculated according

to the summative table below. Remember to compensate for ongoing fluid losses, such as watery stools or vomiting, by giving an additional 10mL/kg per vomit or stool.

Fluid requirement per day

First 10kg 100mL/kg

Second 10kg 50mL/kg

Subsequent kg 20mL/kg

For example: A 25kg child would require 1000 + 500 +100 = 1600mL/day

Management of feeding during rehydration and maintenance phases

Breast Fed

Continue breast-feeding throughout rehydration and maintenance phase

Formula fed

Restart feeding at full strength as soon as rehydration is complete(ideally after 4 hours)

Weaned children

Give the child normal fluids and solids after rehydration. Avoid fatty foods or foods high in simple sugar

Remember to advise the parent(s) or carer about what they should do to prevent spread of gastroenteritis (meticulous hand washing and hygiene). In

general, children can go back to school/nursery as soon as they are symptom-free, and have maintained a satisfactory fluid intake, for around 24 hrs.

Stool microscopy/culture – this is necessary when the child

has frank blood in the stool

has recently returned from abroad

has a history suggestive of food poisoning

appears systemically unwell or has severe or prolonged diarrhoea

is taking, or has recently taken, a broad spectrum antibiotic (request Clostridium difficile toxin detection).

Referral advice

Any child who is 9% or more dehydrated, or showing signs of shock, should be transferred to hospital immediately (????).

Children should be transferred to hospital urgently (???) if:

they will not take, or tolerate, sufficient fluids orally to maintain adequate hydration/urine output

they appear systemically unwell

there is a suspicion that the symptoms might be due to a cause other than acute gastroenteritis.

Most children can be managed at home but will need to be re-assessed regularly. Frequency of assessment will depend on the age of the child and

whether losses continue. Warn parents that stools may take several days (sometimes up to two weeks) to return to normal. If diarrhoea recurs once the child has returned to a normal, or near-normal, diet consider lactose or other intolerance, particularly if there is failure to thrive

Diarrhoea and Vomitting Under 5 NICE

Causes include:

1. Tonsillitis and otitis media

2. Intussusception

3. Meningitismay be atypical in infants

4. Pneumonia

5. Urinary tract infection

6. Gastroenteritis

Parents’ history may not be exact and vomiting may be a nonspecific symptom of an ill baby. Hence vital to examine fully every infant with diarrhoea and/or vomiting’

Management

If serious disease suspected, refer

1. If a simple gastroenteritis, assess dehydration from the length of the history, the frequency of the diarrhoea and vomiting, and the signs

2. Signs of dehydration (occur when baby is> 5% dehydrated)

(i) Loss of skin elasticity doughy skin

(ii) Weight loss

(iii) Oliguria, Le. fewer wet nappies

(iv) Tachycardia and tachypnoea

(v) Sunken eyes with no tears

(vi) Sunken fontanelle

(vii) Dry mouth

(viii) Irritability or lethargy

IF THERE ARE SIGNS OF DEHYDRATION, ADMIT

Management of simple gastroenteritis in infants is:

(i) Advice-no milk or solid food for 24-48 h

(ii) Clear fluids to be given-the ideal is a glucose electrolyte solution, e.g. Dioralyte sachets. Advise small sips often-intake should be about one to one-and-a-half times the usual feed volume

(iii) Review the next day, within 24 h. Tell the parents to contact you earlier if the infant refuses all fluid, the vomiting increases, the infant’s condition deteriorates or other complications develop

(iv) On review, if infant still vomiting or signs of dehydration evident, admit. If child improving, continue Dioralyte and then begin, as symptoms settle, to regrade through % strength to Y2 strength and finally to full strength feeds in 1224-h steps according to progress

(v) Recurrence of diarrhoea occasionally due to lactose intolerance-if so try a soya milk, e.g. Wysoy, for a month

(vi) Social circumstances and parental attitudes obviously important in determining management

(vii) A written advice sheet is helpful

(viii) If breast-fed the baby can continue-giving little and often, supplemented with Dioralyte

DIARRHOEA AND VOMITING IN OLDER CHILDREN

Much more likely to be just a simple gastroenteritis rather than a manifestation of other illness, but remember appendicitis

Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis: diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years NICE C

Perform stool microbiological investigations if:

you suspect septicaemia or there is blood and/or mucus in the stool or the child is immunocompromised

Assessing dehydration and shock

Use table below to detect clinical dehydration and shock

Fluid management

In children with gastroenteritis but without clinical dehydration:

continue breastfeeding and other milk feeds

encourage fluid intake

discourage the drinking of fruit juices and carbonated drinks, especially in those at increased risk of dehydration (see below)

offer oral rehydration salt (ORS) solution as supplemental fluid to those at increased risk of dehydration (see below)

In children with clinical dehydration, including hypernatraemic dehydration:

use low-osmolarity ORS solution (240–250 mOsm/l)* for oral rehydration therapy

give 50 ml/kg for fluid deficit replacement over 4 hours as well as maintenance fluid

give the ORS solution frequently and in small amounts

consider supplementation with their usual fluids (including milk feeds or water, but not fruit juices or carbonated drinks) if they refuse to take sufficient quantities of ORS solution and do not have red flag symptoms or signs (see below)

consider giving the ORS solution via a nasogastric tube if they are unable to drink it or if they vomit persistently

monitor the response to oral rehydration therapy by regular clinical assessment

Use intravenous fluid therapy for clinical dehydration if:

shock is suspected or confirmed

a child with red flag symptoms or signs (see table below) shows clinical evidence of deterioration despite oral rehydration therapy

a child persistently vomits the ORS solution, given orally or via a nasogastric tube

If intravenous fluid therapy is required for rehydration (and the child is not hypernatraemic at presentation):

use an isotonic solution, such as 0.9% sodium chloride, or 0.9% sodium chloride with 5% glucose, for both fluid deficit replacement and maintenance

for those who required initial rapid intravenous fluid boluses for suspected or confirmed shock, add 100 ml/kg for fluid deficit replacement to maintenance fluid requirements, and monitor the clinical response

for those who were not shocked at presentation, add 50 ml/kg for fluid deficit replacement to maintenance fluid requirements, and monitor the clinical response

measure plasma Na, K urea, creatinine and glucose at the outset, monitor regularly, and alter the fluid composition or rate of administration if necessary

consider providing intravenous potassium supplementation once the plasma potassium level is known

Nutritional management

After rehydration:

give full-strength milk straight away

reintroduce the child’s usual solid food

avoid giving fruit juices and carbonated drinks until the diarrhoea has stopped

Information and advice for parents and carers

Advise parents, carers and children that:†

washing hands with soap (liquid if possible) in warm running water and careful drying are the most important factors in preventing the spread of gastroenteritis

hands should be washed after going to the toilet (children) or changing nappies (parents/carers) and before preparing, serving or eating food

towels used by infected children should not be shared

children should not attend any school or other childcare facility while they have diarrhoea or vomiting caused by gastroenteritis

children should not go back to their school or other childcare facility until at least 48 hours after the last episode of diarrhoea or vomiting

children should not swim in swimming pools for 2 weeks after the last episode of diarrhoea

Assessing dehydration

These children are at increased risk of dehydration:

children younger than 1 year, especially those younger than 6 months

infants who were of low birth weight

children who have passed six or more diarrhoeal stools in the past 24 hours

children who have vomited three times or more in the past 24 hours

children who have not been offered or have not been able to tolerate supplementary fluids before presentation

infants who have stopped breastfeeding during the illness

children with signs of malnutrition

Symptoms and signs of clinical dehydration and shock

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————-›

No clinically detectable dehydration Clinical dehydration Clinical shock

Symptoms (remote and FTF assessments)

Appears well Appears to be unwell or deteriorating

Alert and responsive irritable, lethargic Decreased LOC

Normal urine output Decreased urine output

Skin colour unchanged Skin colour unchanged Pale or mottled skin

Warm extremities Warm extremities Cold extremities

Signs (remote and FTF assessments)

Alert and responsive irritable, lethargic Decreased level of consciousness

Skin colour unchanged Skin colour unchanged Pale or mottled skin

Warm extremities Warm extremities Cold extremities

Eyes not sunken Sunken eyes

Moist mucous membranes (except after a drink) Dry mucous membranes (except for ‘mouth breather’)

Normal heart rate Tachycardia Tachycardia

Normal breathing pattern Tachypnoea Tachypnoea

Normal peripheral pulses Normal peripheral pulses Weak peripheral pulses

Normal capillary refill time Normal capillary refill time Prolonged capillary refill time

Normal skin turgor Reduced skin turgor

Normal blood pressure Normal blood pressure Hypotension

Umbilical problems

Umbilical hernia

Will usually resolve within first year – 2 years. surgical intervention is not advised before the third year, unless the neck of the hernia is larger than 2 cm at the time of the child’s first birthday, in which case spontaneous closure is very unlikely.

Paraumbilical hernia rarely resolve and will need surgical correction after the age of 2-3 years

Undescended testes

Undescended Testes @ Patient UK

Breast buds

Neonatal vaginal discharge and bleeding

Maternal oestrogens and progestogens from the placenta cross over into the foetal blood system causing development of the foetal endometrium.

Abrupt withdrawal of these hormones after birth causes atrophy and shedding of the mucosa causing a mucus / bloodstained discharge

source GPCSG

Hormonal Effects in Newborns medicine online.com

Pyloric stenosis

<a href=”http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/803489-overview>Pyloric stenosis Medscape

Pyloric Stenosis information for parents GOSH

Intussusception

Circumcision

Enuresis

Failure to voluntarily control micturition. Can be diurnal or nocturnal.

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG111

Most children are dry at night by 4 years.

Age % wetting

5 11

10 5

15 2

Ten per cent of 5-year-olds wet their beds.

Treatment is justified after the age of 4 years

History

1. Primary or secondary? Secondary may be emotional or organic

2. Other symptoms, e.g. dysuria, abdominal pain

3. Family history

4. Is the child developing normally, both mentally and physically

5. Family stress

6. Parental expectations

Examination

1. Examine the back and lower limbs for anatomical anomalies or lesions of the lower spinal cord

2. Palpate the abdomen for kidneys and bladder and examine the external genitalia of boys

Tests

MSU and dipstick urine if appropriate

Management

With no anomalies, neuropathic bladder or UTI, the management is:

1. Advice, e.g. lifting the child before going to sleep