Cardiovascular System: Blood

Blood is a very unique connective tissue type because it is a fluid. All connective tissues contain cells, ground substance, and fibers. Blood contains many “cell” types (erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets) and lots of ground substance (plasma). However, the fibers in blood are dissolved in the plasma, making them impossible to see on light microscopy. The protein fibers must be dissolved for the blood to flow freely through our vessels. These soluble protein fibers are activated during blood clotting to become an insoluble protein meshwork that helps to plug damaged blood vessels.

Formed Elements

We refer to the “cells” in blood as formed elements because most of the “cells” don’t fit the usual criteria to be called cells at all. Instead, we call the cellular structures formed elements. The most abundant formed elements, erythrocytes (red blood cells) and platelets, do not contain a nucleus. In fact, the only formed element that contains a nucleus are the leukocytes (white blood cells).

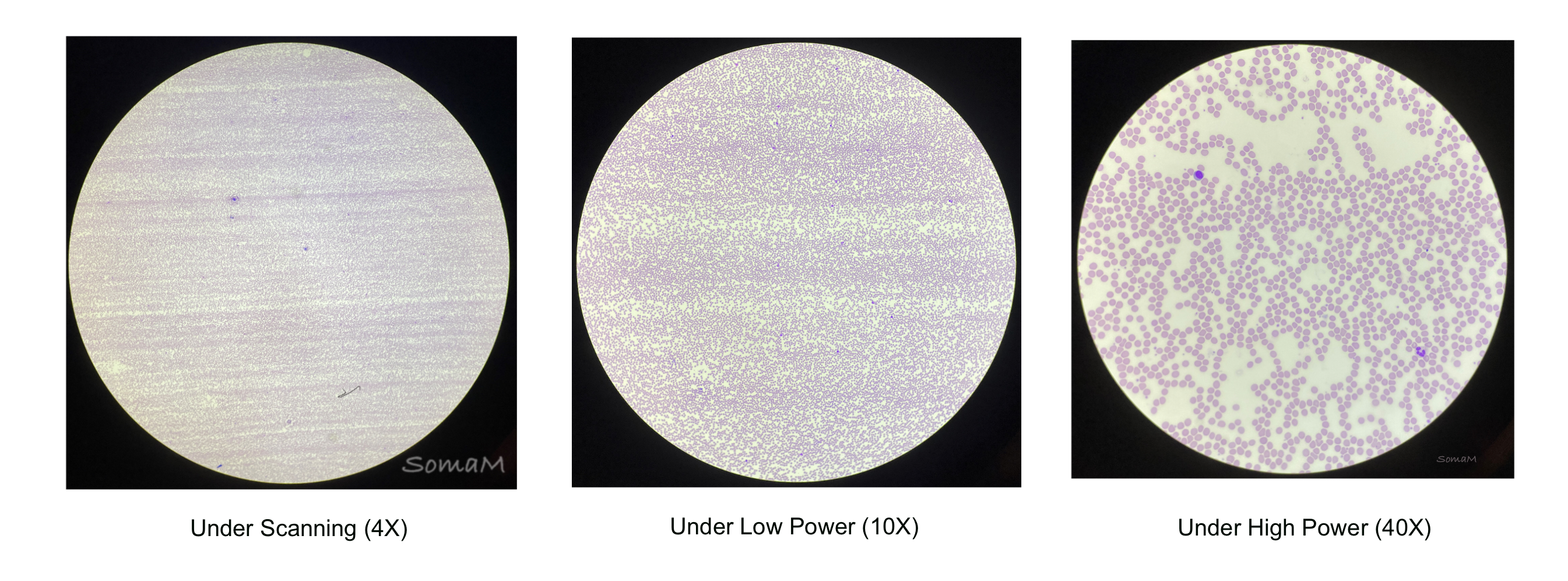

Figure 1: Blood smear under varied magnification – scanning objective lens (4x, left), low power lens (10x, center), and high power lens (40x, right)

Figure 2: Blood smear with types of formed elements identified, with and without illustration overlay

Erythrocytes

Erythrocytes (red blood cells) have no nucleus, so we refer to them as anucleate. Erythrocytes contain virtually no organelles and are filled with millions of molecules of hemoglobin, which helps to transport O2 and CO2. Erythrocytes have a biconcave shape, which allows for easier diffusion of O2 and CO2 into and out of the cell.

Remember that erythrocytes are anucleate, so you are looking for cells that lack the typical blue/purple central nucleus structure found in other cell types. Instead, look for pale pink circular cells that may have a white area in the center (Figure 2).

Platelets

Platelets are cell fragments derived from a large cell called a megakaryocyte trapped in the bone marrow. Platelets are are important in blood clotting. On microscopy, they are often mistaken for cellular debris (Figure 2).

Leukocytes

Leukocytes (white blood cells) are the only nucleated cells in blood (Figure 2). Leukocytes are important for our immune function. The five types of leukocytes are grouped into two categories: granulocytes (have prominent-staining cytoplasmic granules) and agranulocytes (without prominent-staining cytoplasmic granules). Granulocytes include neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. Agranulocytes include monocytes, and lymphocytes.

Neutrophils are the most common of the leukocytes, making up 55-70% of all leukocytes in the blood1. They have a multilobed nucleus (3 to 5 lobes) and small granules that tend to stain light purple/blue. The cytoplasm of the neutrophil stains pale pink. Neutrophils have the ability to move out of the blood and into the surrounding tissues at sites of infection/inflammation. Often called bacteria “slayers,” they function in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris.

Figure 3: Leukocytes: neutrophils with illustration overlay

Eosinophils make up approximately 1-4% of all leukocytes in the blood. They primarily have a bilobed nucleus with large cytoplasmic granules stained dark pink/red. The granules contain a variety of proteins and enzymes that are toxic to parasites, like parasitic worms. These cells are also know to play a role in allergies and asthma.

Figure 4: Leukocytes: eosinophil with illustration overlay

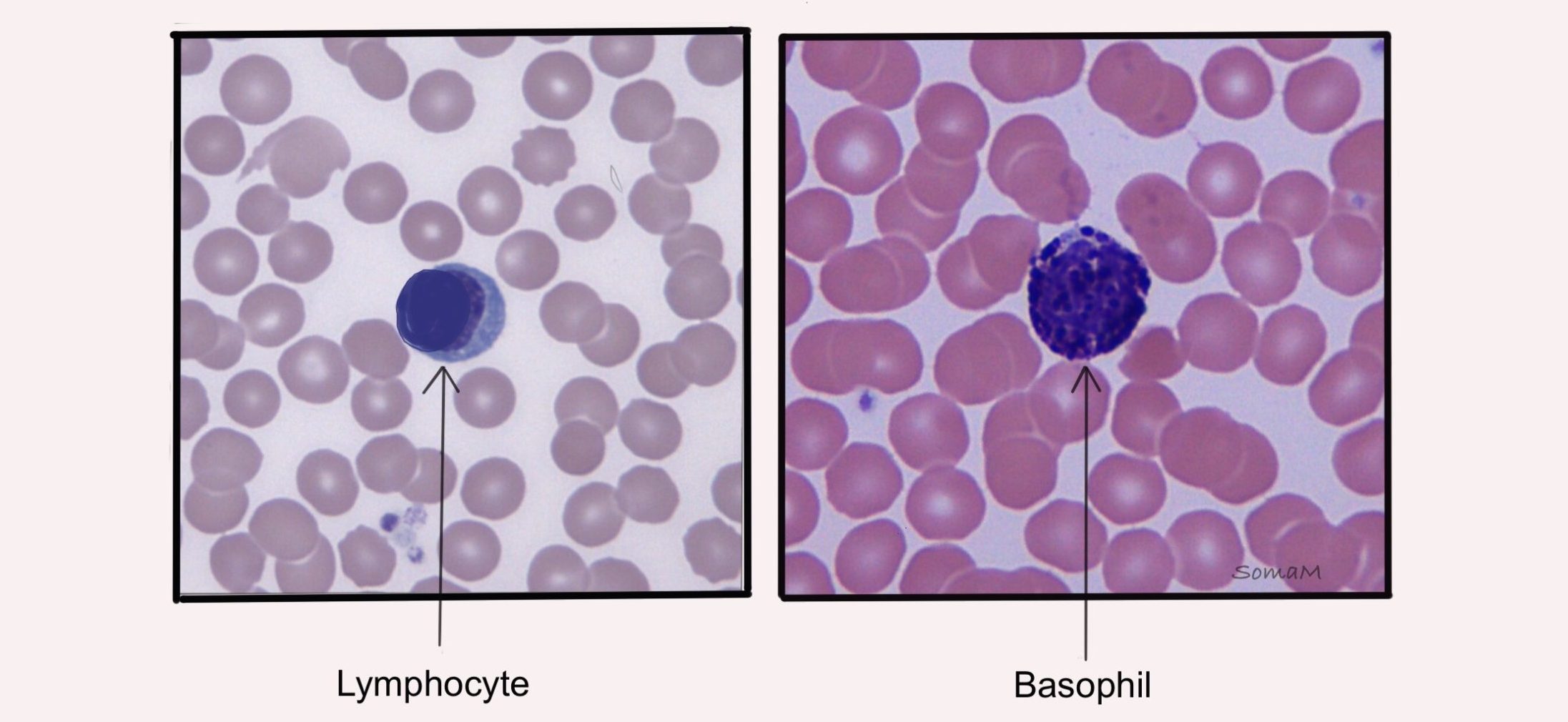

Basophils are the least abundant of the leukocytes, making up less than 1% of all leukocytes in the blood1. Like eosinophils, they primarily have a bilobed nucleus, but their large cytoplasmic granules stain dark purple/blue. The darkly-staining granules can make it difficult to see the nucleus. These cells release chemicals, such as histamine, that regulate inflammation. Basophils also play a role in allergies and prevention of blood clots.

Figure 5: Leukocytes: basophil with illustration overlay

Lymphocytes are the most common leukocytes following neutrophils (20-40% of leukocytes in the blood1). Lymphocytes tend to be smaller than the other leukocytes and have spherical nuclei. These cells are very important in adaptive immunity. When inactive they have only a small amount of cytoplasm visible that stains light purple/blue. When activated, the cytoplasm becomes more abundant. There are two main types of lymphocytes, B-cells and T cells. B-lymphocytes produce antibodies which help destroy bacteria, while T-lymphocytes help fight infections through cell-targeted attacks.

Figure 6: Leukocytes: lymphocytes with illustration overlay

Monocytes are low abundance and make up about 2-8% of leukocytes in the blood1. Monocytes are the largest of the leukocytes. They often have a U-shaped or kidney-shaped nuclei with abundant cytoplasm that stains light purple/blue. Similar to neutrophils, monocytes have the ability to move out of the blood and into the surrounding tissues at sites of infection/inflammation. Once in the tissue, monocytes differentiate into macrophages that phagocytose pathogens and debris.

Figure 7: Leukocytes: monocytes with illustration overlay

Table 1. Structure and function of the five leukocytes

| Leukocyte | Structure | Function | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil | Cell with pink cytoplasm and a multilobed nucleus (3 to 5 lobes) with small granules that tend to stain light purple/blue. | Function in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris. | 55-70% |

| Eosinophil | Cell with a bilobed nucleus and many large cytoplasmic granules stained dark pink/red. | Help fight off parasitic infections. | 1-4% |

| Basophil | Cell often with a bilobed nucleus and many large cytoplasmic granules that stain a very dark purple/blue. | Help regulate inflammation by releasing histamine. | < 1% |

| Lymphocyte | Cell with a spherical nuclei. Inactivated cells have very little cytoplasm that stains a light purple/blue. | Produces antibodies and helps fight pathogens through direct cell attack. | 20-40% |

| Monocyte | Large cell, often with a U-shaped or kidney-shaped nucleus. Cytoplasm stains a light purple/blue. | Monocytes differentiate into macrophages that phagocytose pathogens and debris. | 2-8% |

Students often have a difficult time differentiating lymphocytes from basophils under the microscope. Both cells often stain as dark round cells. However, the lymphocyte stains dark due to the large spherical nuclei taking up the majority of the cell, while the basophil stains dark due to the dark-staining granules filling the cytoplasm.

Figure 8: Differences between lymphocytes and basophils

sickle cell

Erythrocytes are disc-shaped and flexible so they can move easily through the blood vessels. Sickle cell disease is a genetic disease that results in “sickle”-shaped erythrocytes. This is due to a genetic mutation that results in the production of abnormal hemoglobin. In Figure 9, the erythrocytes of a normal blood smear appear disc-shaped while for the sickle cell blood smear has several erythrocytes with a “sickle” shape. These sickle-shaped erythrocytes get stuck in small vessels, blocking blood flow. This, coupled with the mutated hemoglobin, decreases the oxygen-carrying capacity in these patients.

Figure 9: Micrograph of normal blood smear and sickle cell blood smear with illustrated overlays

CHapter Citation

-

Curry, C. V., MD. Differential blood count: reference range, interpretation, collection and panels. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2085133-overview

Chapter Illustrations By:

Soma Mukhopadhyay, Ph.D.