Urinary System

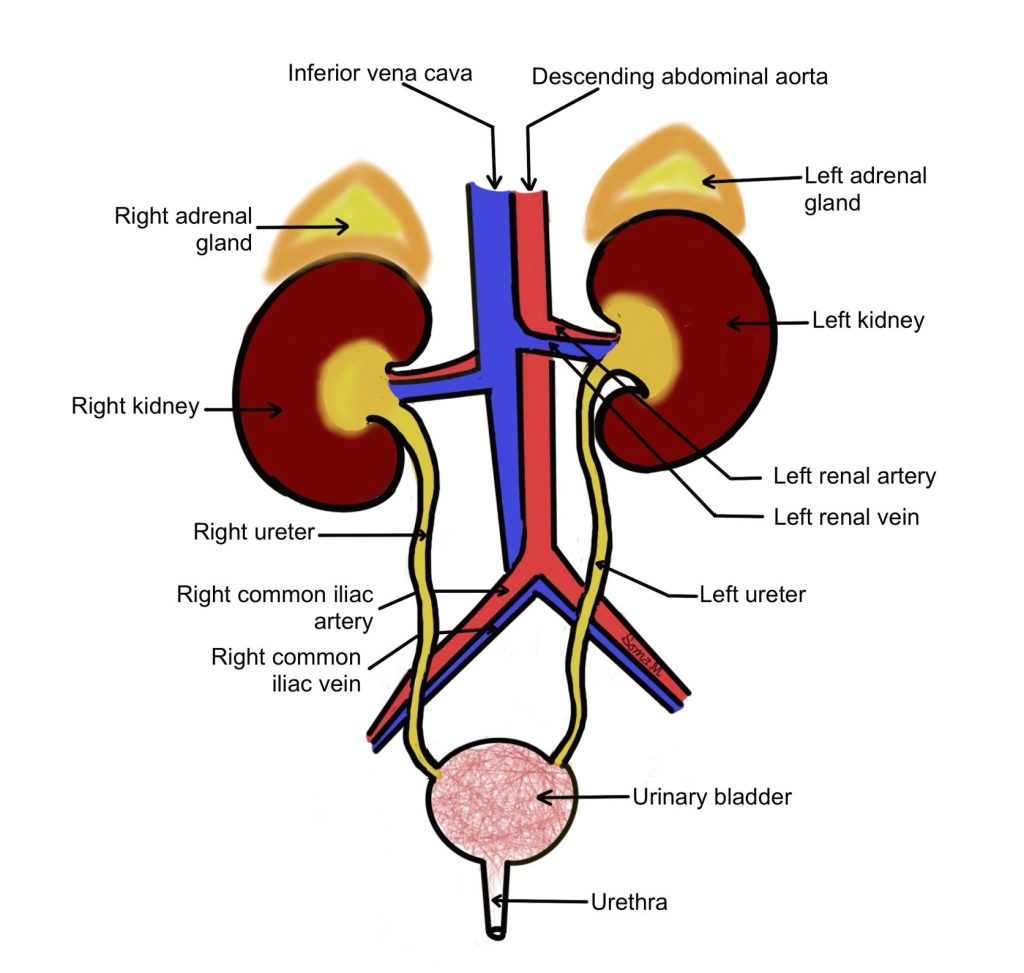

The function of the urinary system is to ensure homeostasis of our blood’s composition. The kidney filters the blood, ensures appropriate water and solute composition, and excretes any excess fluid and solutes as urine. The urine is transported from the kidneys to the urinary bladder by the ureters. Urine exits the body through the urethra (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Organs of the urinary system with major blood vessels of the abdominopelvic cavity

Organs of the Urinary System

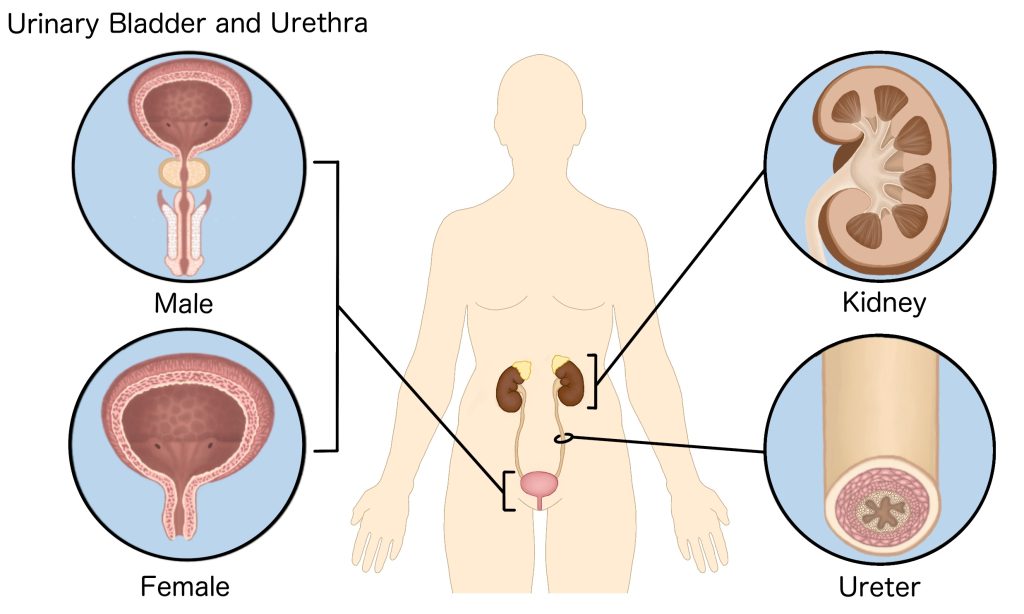

The urinary system consists of several organs with different histology. Urine is produced by the kidneys, which are composed of millions of elaborate structures called nephrons. Urine produced by the kidneys travels through the ureters, hollow tubes, to the urinary bladder. The urinary bladder is a heavily muscular organ that has tremendous capacity to stretch. Urine leaves the body through the urethra. Reflecting differences in external reproductive system anatomy, the urethra in females is much shorter than the urethra of males (Figure 2).

Histology of the kidney

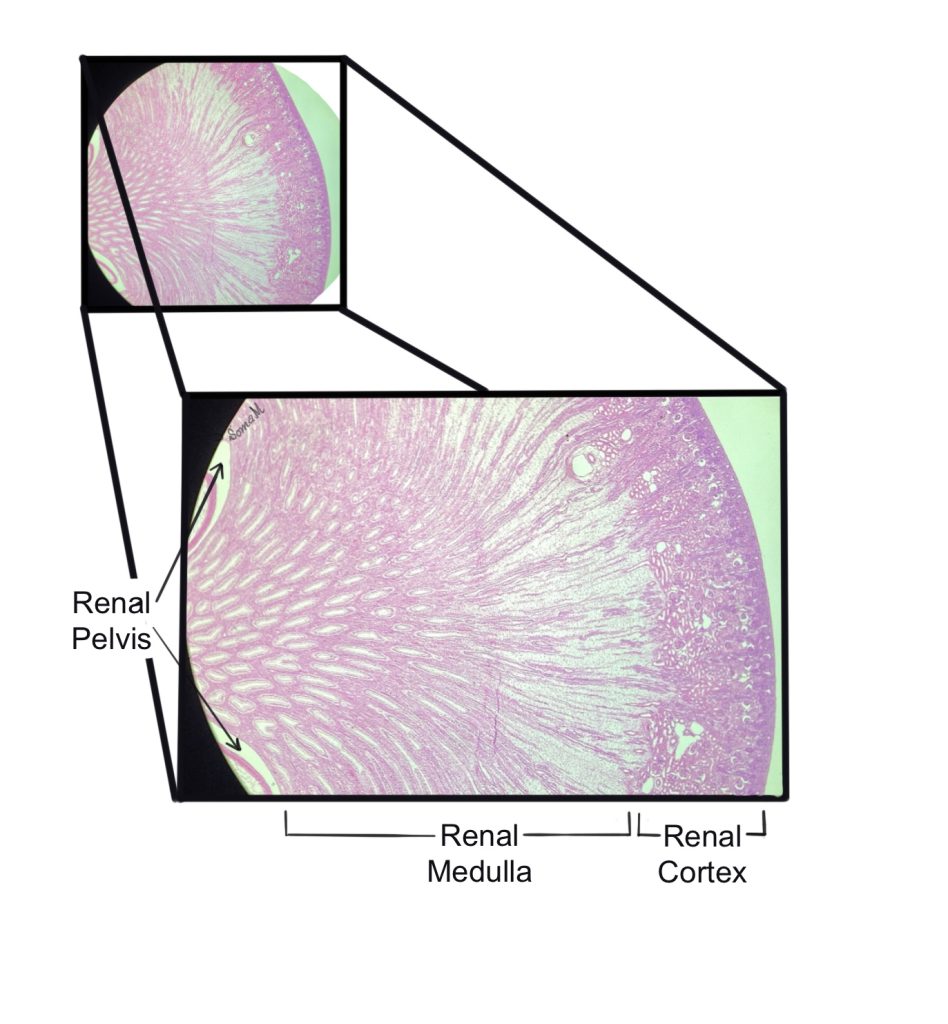

First, we will discuss the histology of the kidney. The kidney is divided into two distinct regions: the outer cortex, and inner medulla (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Low power view of the internal regions of the kidney

Each kidney contains approximately one million nephrons, which are the functional unit of the kidney. Most of the nephron’s structure is located in the cortex (more details to follow). The nephron ensures appropriate solute and water composition of the blood. The nephron does this through three distinct processes: filtration, reabsorption, and secretion.

- Filtration is the process by which fluids and solutes are forced out of the blood vessel at the glomerulus and enter the nephron’s renal tubule

- Reabsorption is the process of membrane transport of solutes and water from renal tubule of nephron into the blood

- Secretion is the process of membrane transport of water and solutes from the blood into renal tubule of nephron

Urine, containing excess fluid and solutes, drains into collecting ducts. Collecting ducts extend from the cortex through the medulla and urine spills from the collecting duct into the minor calyx. Multiple minor calyces (singular, calyx) merge into one major calyx. The major calyces join to form the renal pelvis, which is continuous with the ureter as it exits the kidney. The ureter transports urine into the urinary bladder. Figure 4 shows the internal structures of the kidney. Keep in mind that the image has been simplified and does not include the entire vascular supply.

Figure 4: Internal structure of the kidney

The nephron

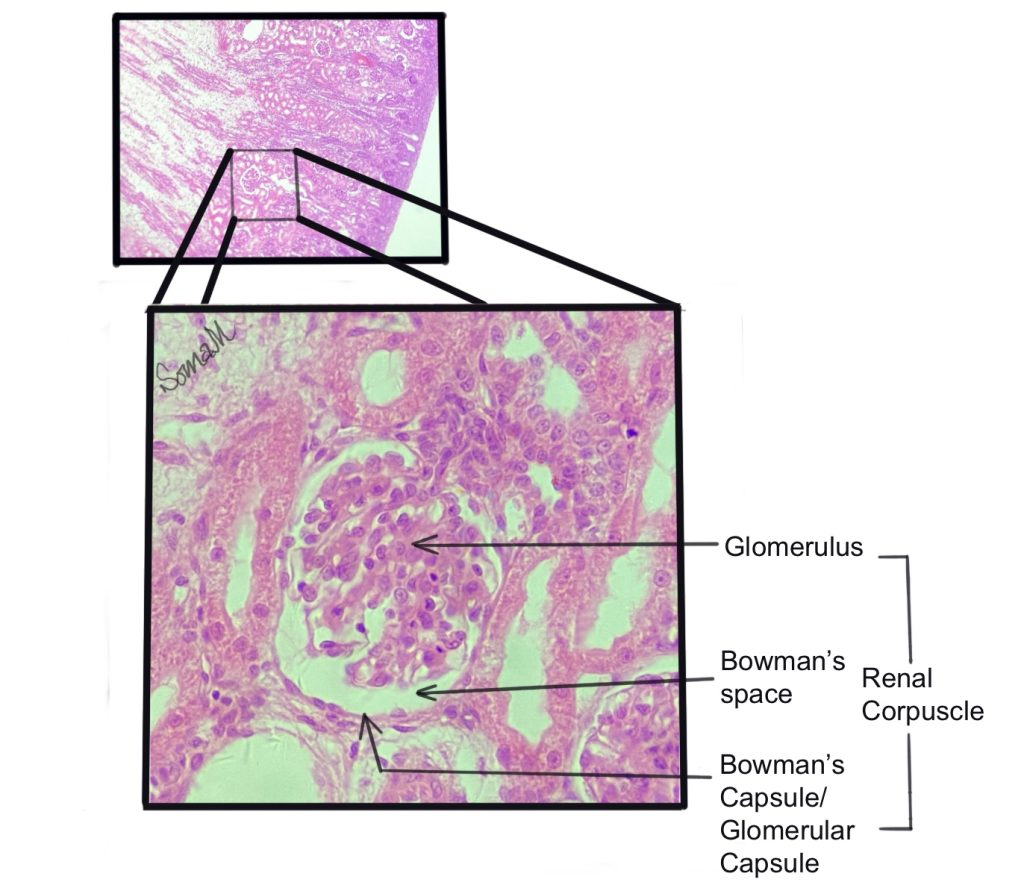

The nephron contains two major parts: the renal corpuscle and the renal tubule. The renal corpuscle, shown in Figure 5, contains the glomerulus (a bundle of capillaries) surrounded by Bowman’s capsule (a bowl-like structure of simple squamous epithelium). Between the glomerulus and Bowman’s capsule is the capsular space (empty space with low pressure). Fluids and solutes are bulk filtered out of the blood vessels of the glomerulus and enter the capsular space before emptying into renal tubule.

Figure 5: The renal corpuscle

The fenestrated glomerular capillaries are surrounded by cells called podocytes (podo- meaning foot, and -cyte meaning cell) which form filtration slits. Together the capillaries and the podocytes (blue cells in Figure 7 and green cells in Figure 9) help to form the filtration membrane. The filtration membrane allows bulk filtration of fluids and small solutes into Bowman’s space (yellow space in Figure 7), but keeps larger structures like formed elements and plasma proteins in the blood vessel.

Following filtration, the fluid and solutes that move from Bowman’s space into the renal tubule are referred to as filtrate. The renal tubule is composed of three distinct regions with different functions: the proximal convoluted tubule, the loop of Henle (nephron loop), and the distal convoluted tubule (Figure 6).

To align with the histology-focus of this book, we will dramatically simplify the functions of each region of the renal tubule. Please consult your lecture textbook for more detailed functions. The proximal convoluted tubule is the primary site of solute reabsorption. Reabsorption refers to the process of water and solutes moving from the renal tubule (filtrate) back into the blood plasma. The lumen of the proximal convoluted tubule is surrounded by simple cuboidal epithelium containing microvilli on the apical surface. These microvilli increase surface area available for reabsorption. The cells surrounding the lumen of the proximal convoluted tubule have a fuzzy edge due to the microvilli.

The loop of Henle or nephron loop is the site of sodium (Na+) and water balance. The loop of Henle extends into the medulla and has a descending limb and ascending limb that are selectively permeable to water and sodium, respectively (Figure 6). The loop of Henle has thin and thick sections which contain squamous and cuboidal epithelium, respectively . Filtrate then moves from the loop of Henle into the distal convoluted tubule, which is the site of selective secretion from the blood plasma in the filtrate. The lumen of the distal convoluted tubule is surrounded by simple cuboidal epithelium but has much less microvilli content on the apical surface. As a result, the cells surrounding the lumen of the distal convoluted tubule appear to have a smooth edge. From the distal convoluted tubule, the filtrate empties into collecting ducts. Reabsorption of water occurs in the collecting duct, which helps to concentrate the urine that is produced. Several hormones act on the cells of the of the nephron to impact its function (antidiuretic hormone, aldosterone, parathyroid hormone).

Figure 6: The parts of a nephron with and without labels

Figure 7: Cortical structures (glomerulus and renal tubule) with and without illustration overlay

Vascular structures associated with the Nephron

The previous section discussed movement of fluid and solutes from the glomerulus into the nephron and through the lumen of the nephron’s renal tubules. This section will discuss the corresponding vascular structures. While it does not illustrate the entire vascular supply of the kidney, Figure 8 illustrates the major vascular structures. Blood enters the kidney through the renal artery, which branches into segmental arteries, and then branches into interlobar arteries which pass between medullary pyramids. The interlobar arteries branch into arcuate arteries, which run laterally between medulla and cortex. Branching off of the arcuate arteries are cortical radiate arteries (or interlobular arteries) which extend or radiate outward through the cortex. Afferent arteries, each supplying one nephron, branch off of the cortical radiate artery.

Figure 8: Vasculature of the kidney

Figure 9 offers a more detailed view of the nephron with its associated blood vessels. As shown in Figure 9, arterial blood enters the nephron through the afferent arteriole. The afferent arteriole brings arterial blood into the glomerulus, which is an elaborate tuft or ball of capillaries. Blood leaves the glomerulus through the efferent arteriole, which will continue to become the peritubular capillaries. The peritubular (peri- meaning around) capillaries surround the renal tubules, allowing reabsorption and/or secretion of fluids and solutes to/from the blood vessel. The loop of Henle is surrounded by a set of long branching vessels called the vasa recta, which extend into the medulla. Venous blood from these structures merges into the cortical radiate vein. Blood then leaves the kidney through the renal vein and returns to the heart.

Figure 9: The nephron with and without corresponding vasculature

The juxtaglomerular Complex

The juxtaglomerular complex (or juxtaglomerular apparatus) is part of the nephron, and is involved in the maintenance of both glomerular filtration rate and systemic blood pressure. It is found between the glomerulus and the late/distal ascending limb of the loop of Henle of the corresponding nephron (note: the prefix juxta means “next to”, so juxtaglomerular means next to the glomerulus). The juxtaglomerular complex contains three special types of cells:

- Macula densa cells are part of the epithelium of the late/distal ascending limb of the loop of Henle closest to the glomerulus.

- Granular cells are located in the tunica media of the afferent arterioles.

- Extraglomerular mesangial cells are located in the junction between the afferent and efferent arterioles.

The macula densa acts as a sensor of the amount of NaCl in the filtrate. The juxtaglomerular complex can control the amount of filtrate produced in the glomerulus by controlling the diameter of the afferent arteriole. This mechanism call also be used to affect systemic blood pressure.

Figure 10: The juxtaglomerular complex of the nephron

Figure 11: Cortical structures including the macula densa with and without illustration overlay

Histology of the urinary bladder

The urinary bladder is an organ which allows a great deal of stretch but contains muscle tissue that contracts during the process of urination (micturition). The wall of the urinary bladder contains epithelium (more on this to follow) anchored to basal lamina. Deep to the lamina propria will be three poorly defined layers of muscle tissue (detrusor muscle). The pattern of these layers are opposite from the pattern seen in the GI system. The urinary bladder has an inner longitudinal layer and middle circular layer (outer longitudinal layer is not seen in Figure 12).

Figure 12: Tissue layers of the urinary bladder

The lumen of the urinary bladder is lined with transitional epithelium (urothelium), which allows the organ to stretch (as it fills) and recoil (as it empties) without damaging the epithelium. Students often confuse transitional epithelium with stratified epithelium. In stratified epithelium, the shape of the cell looks different due to cellular changes that occur as the cell migrates from the basal side to the apical side. This “transition” is NOT what the name transitional epithelium refers to! Transitional epithelium is made of cells that can transition or change their shape depending on whether the tissue is relaxed (big round balloon cells or umbrella-shaped) or stretched (cells are pulled flat).

Transitional epithelium is found in organs that must stretch a lot (urinary bladder and ureters). Think about how small your urinary bladder is when it is empty (holds about 20 mL) and when it is full (typically holds 500-700 mL but can hold more!). Connective tissue and muscle tissue are quite stretchy/elastic. Epithelial tissue typically resembles a brick wall and is not very stretchy/elastic. The special property of the transitional epithelial tissue lining the inside of the bladder allows it to stretch so the urinary bladder to hold a large volume.

This phenomenon is most visible in the cells of the apical layer, which look enormously oversized with a tiny nucleus when the cell is relaxed (Figure 13, 14, and 15). In some slides, these cells may have an umbrella shaped nucleus (flat on bottom, curved on top). We can see this transitional phenomenon in Figure 13. On the left side of Figure 13 the tissue is stretched and the cells looked flattened. However, on the right side of Figure 13 the tissue is relaxed and the apical cells look bulged and oversized.

Figure 13: Transitional epithelium of the urinary bladder with and without illustration overlay (version A)

Figure 14: Transitional epithelium of the urinary bladder with and without illustration overlay (version B)

Figure 15: Transitional epithelium of the urinary bladder with and without illustration overlay (version C)

Chapter Illustrations By:

Juan Manuel Ramiro Diaz, Ph.D.

Georgios Kallifatidis, Ph.D.

Soma Mukhopadhyay, Ph.D.

Karis Le

a specialized type of capillary that has small pores/holes allowing fluids and solutes to leave the blood vessel