Digestive System: Organs of the Alimentary Canal

The next two chapters will discuss the histology of the digestive system. To keep things organized, we will divide the content into two parts: organs of the alimentary canal and accessory organs of digestion (liver, pancreas, salivary glands). This chapter will focus on histology of the organs of the alimentary canal, also known as gastrointestinal tract. Accessory organs of digestion will be discussed in the next chapter: Digestive System: Accessory Organs of Digestion

Histology of the Organs of the Alimentary Canal

The organs in the alimentary canal share the same general pattern of tissue layers. This section will discuss the shared general pattern of tissue layers found in each organ (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, ileum, colon). Separate sections will discuss unique characteristics of each organ.

The alimentary canal is a long hollow tube with a central empty space called the lumen. The food, as it passes through the digestive system, is found in the lumen. The tissue layers working from the lumen outward are:

Mucosa – contains epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae

Submucosa – contains connective tissue, blood vessels/lymphatic vessels/nerves

Muscularis Externa – typically two layers of muscle tissue; inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer

Serosa/Adventitia – outermost thin layer of connective tissue and mesothelium (epithelium)

The mucosa layer contains a layer of epithelium anchored to the basement membrane found within the lamina propria. The lamina propria contains smaller blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The deepest/outermost part of the mucosa is the muscularis mucosae, which is a thin layer of smooth muscle tissue. The mucosa may contain exocrine glands that vary in both structural arrangement and function (product produced) for each part of the alimentary canal, which will be discussed later.

The submucosa layer contains larger blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves embedded in connective tissue. The submucosa may contain exocrine glands, which will be discussed later.

The muscularis externa layer typically consists of 2 layers of smooth muscle tissue. The layers of muscle tissue are orthogonal, which means that the cells are oriented at right angles (perpendicular) to each other. The inner layer is the circular layer, and the outer layer is the longitudinal layer. The circular layer has smooth muscle cells oriented in a ring around the lumen. The longitudinal layer has smooth muscle cells oriented along the length of the tube. The stomach has a third layer of muscle tissue (oblique layer), which will be discussed later.

The serosa/adventitia layer is outermost layer of connective tissue (and mesothelium for serosa). Organs surrounded by peritoneum in the abdominal cavity (intraperitoneal; stomach, small intestine, first 2/3 of large intestine) are surrounded by serosa. Organs not surrounded by peritoneum in the abdominal cavity (extraperitoneal; esophagus, last 1/3 of large intestine) are surrounded by adventitia.

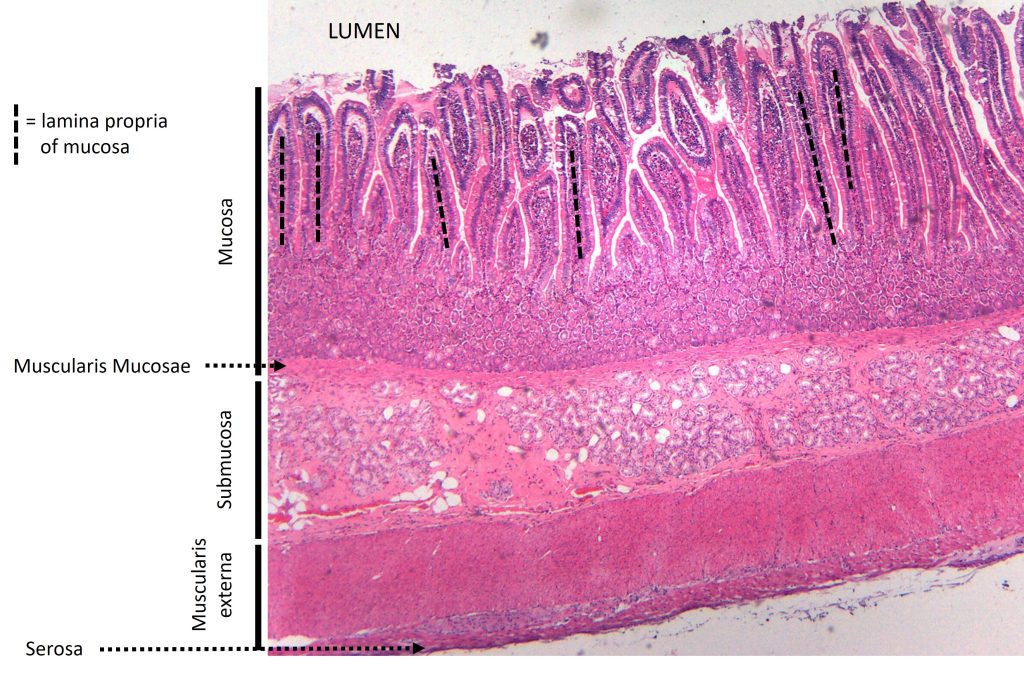

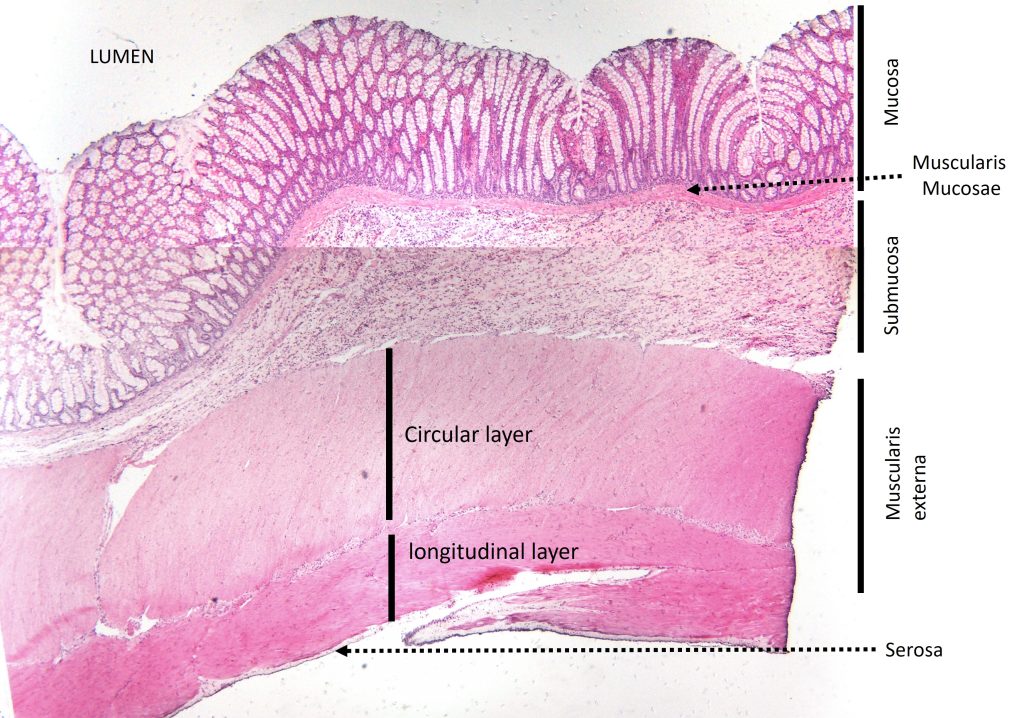

Figure 1 and 2 show micrographs of the small and large intestine in which the different tissue layers have been labeled. We will revisit these micrograph images later in this chapter as we explore these organs in more detail. However, notice that the order of layers is the same in each organ.

Figure 1: Tissue layers of the small intestine

Figure 2: Tissue layers of the large intestine

Histology of the Esophagus:

The esophagus is the first section of the alimentary canal and extends from the oropharynx (part of pharynx posterior to the oral cavity) to the stomach. The function of the esophagus is to facilitate propulsion of the bolus of food that we swallow from the oral cavity inferiorly through the thoracic cavity (past the heart and lungs) into the abdominopelvic cavity where it empties into the stomach. No digestion or absorption occurs in the esophagus. The mucosa of the esophagus contains non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium anchored to the lamina propria. Because no absorption occurs in the esophagus, this stratified squamous epithelium serves a protective function. The food we eat that is hot, scratchy, or acidic typically does not cause lasting damage to the esophagus because of the many cell layers of the stratified squamous epithelium. The muscularis mucosae (smooth muscle aids) in swallowing.

The submucosa of the esophagus contains numerous mucus-secreting glands called seromucous glands or esophageal glands. The mucus is secreted onto the lumen surface to lubricate passage of food along the epithelium. The submucosa also contains scattered pockets of lymphoid tissue, which provides local immune support. The muscularis externa contains an inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer of muscle tissue. Because swallowing is a conscious, voluntary action, the upper portion of the muscularis externa of the esophagus contains skeletal muscle tissue (voluntary) and the lower portion of the esophagus contains smooth muscle tissue (involuntary).

Figure 3: Layers of the esophagus with and without illustration overlay

Histology of the Stomach

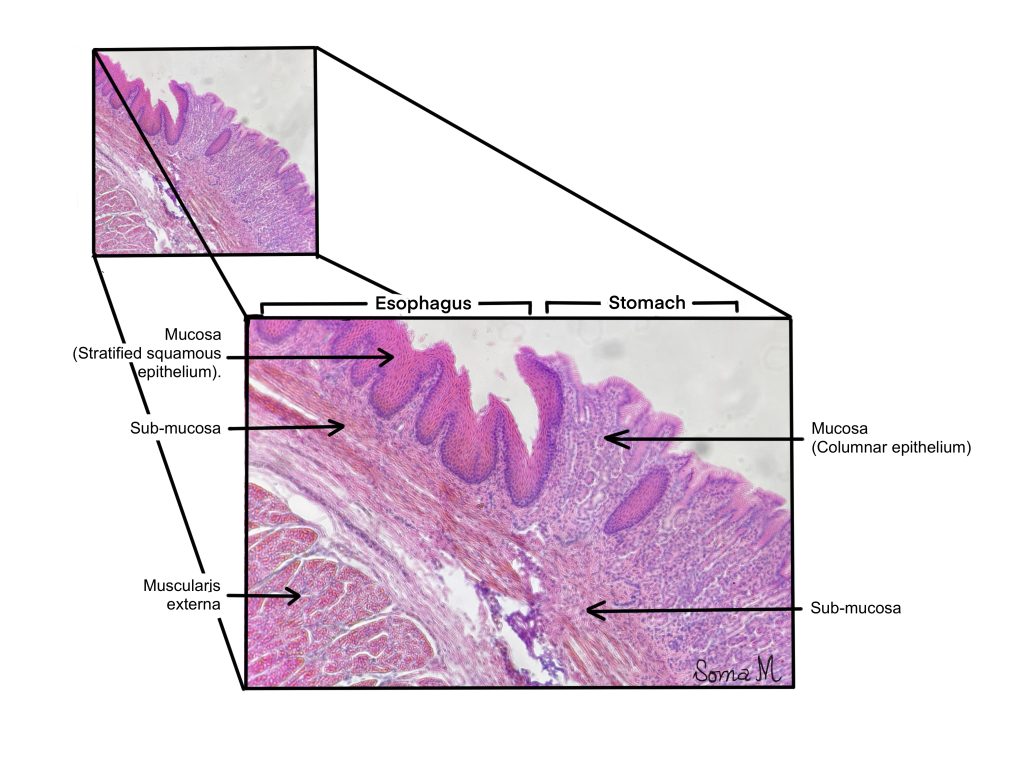

Between the esophagus and the stomach there is an abrupt change in the histological characteristic of the mucosa. The esophagus contains stratified epithelium, while stomach contains simple epithelium. This dramatic change is shown on Figure 4.

Figure 4: Junction between esophagus and stomach

Food passes from the esophagus into the stomach, which serves as a holding chamber. Before the meal can move from the stomach to the small intestine, it must be converted into a liquid-like paste (chyme). The stomach produces acid which denatures proteins and an enzyme which begins the process of protein chemical digestion. The stomach contains a third layer of muscle (oblique layer), which together with the circular and longitudinal layers allow the stomach to mix, churn, and pummel the meal consumed into a homogeneous liquid-like paste. The internal surface of the stomach is not smooth and contains significant folds called rugae. The rugae flatten out and become less prominent when the stomach stretches as it is filled.

The wall of the stomach has the same pattern of layers as other alimentary canal organs. The mucosa of the stomach contains simple columnar epithelium, which contains gastric glands (more on this in the next paragraph), a thin layer of lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae. The muscularis mucosa separates the mucosa from the submucosa and is a good visual landmark (Figure 5, pink line). The submucosa in the stomach is thick and contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. The muscularis externa contains 3 layers of smooth muscle tissue instead of the typical 2 layers; inner oblique layer, middle circular layer, and outer longitudinal layer.

Figure 5: Layers of the stomach with and without illustration overlay

The mucosa of the stomach does not create a flat surface. Instead, the stomach mucosa is covered with gastric pits that invaginates (infoldings) toward the submucosa. Deep in the gastric pits are gastric glands, which contain many types of cells that secrete different products. The cells that line the sides of the pits secrete mucus to protect the cells of the stomach from the acid and enzymes essential for digestion of food (Figure 6, orange cells). Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is secreted from cells called parietal cells (Figure 6, green cells), which have the appearance of a fried egg (large round cells with a small nucleus surrounded by lots of cytoplasm). Parietal cells also secrete intrinsic factor, which is essential for proper absorption of vitamin B12 (important for erythrocyte production). The enzyme pepsin plays a major role in the chemical digestion of proteins in the stomach. It is secreted in an inactive precursor form, pepsinogen, by chief cells (Figure 6, blue cells). Chief cells are small cells with excentric (not centrally-located) nuclei located near the base of the gastric glands.

Figure 6: Mucosa of the stomach with and without illustration overlay

General Histology of the Small Intestine

Chyme passes from the stomach to the duodenum of the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter. The mucosa of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) is responsible for absorption of biomolecules (amino acids, lipids, monosaccharides, nucleotides) and vitamins/minerals from our food. To accomplish this, the mucosa is made of simple columnar epithelium that is arranged into folds (circular folds or plique circularis) that extend into the lumen. These folds slow down the speed of flow through the intestines and increase the surface area available for absorption. These folds are covered in finger-like projections of mucosa called villi (singular is villus). The villus structure is shown in Figure 7. Each villus has a core of lamina propria (Figure 7, orange) surrounded by a layer of simple columnar epithelium (Figure 7, blue cells).

The lamina propria contains blood vessels and lymphatic vessels (lacteals) responsible for transport nutrients absorbed by the epithelial cells in this layer, called enterocytes. The enterocytes contain microvilli on their apical surface, which resemble a brush, so this is often called the brush border. Digestive enzymes, called brush border enzymes are anchored to the apical surface of the microvilli. The circular folds (millimeters in size), villi (micrometers in size), and microvilli (nanometers in size) each increase the surface area available for absorption of nutrients. Along the length of the small intestine, there are two layers of muscularis externa (inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer).

Figure 7: Mucosa of the duodenum with and without illustration overlay

Histology of the duodenum of the small intestine

The duodenum is the first, and very short, section of the small intestine that receives exocrine secretions from the pancreas (enzymes and bicarbonate) and gall bladder (bile and bicarbonate). While it contains the same tissue layers as the other sections of the small intestine (jejunum and ileum), the duodenum has some unique characteristics that we will discuss in this section (Figure 8). The cells of villi of the duodenum invaginate towards the muscularis mucosae to form intestinal crypts or crypts of Lieberkühn. The intestinal crypts are surrounded by lamina propria. The muscularis mucosae forms the barrier between the intestinal crypts of the mucosa and the tissue of the submucosa. The submucosa of the duodenum contains numerous glands called duodenal glands or Brunner’s glands. These glands secrete alkaline (basic) mucus that together with the bicarbonate from the pancreas neutralizes the acidic chyme entering the small intestine from the stomach (Figure 8 and Figure 9, orange glands).

In addition to these glands, the submucosa contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerves. The muscularis externa of the duodenum contains two layers of smooth muscle tissue: inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer.

Figure 8: Tissue layers of the small intestine with and without illustration overlay

Figure 9: Mucosa and submucosa of the duodenum with and without illustration overlay

Histology of the ileum of the small intestine

The ileum is the final section of the small intestine. While it contains the same tissue layers as the other sections of the small intestine (duodenum and jejunum), the ileum has some unique characteristics that we will discuss in this section. The submucosa of the ileum does not contain the seromucous glands seen in the duodenum. This makes sense because the chyme has already been neutralized earlier in the small intestine. Instead, the submucosa of the ileum contains abundant lymphoid tissue. The ileum is the final section of small intestine and empties into the large intestine/colon, which contains numerous species of bacteria. To prevent harmful growth of these bacteria in the small intestine, the submucosa of the ileum contains abundant lymphoid tissue. The lymphoid nodules called Peyer’s patches provide immune support and lymphocyte proliferation.

Figure 10: Mucosa of the ileum with and without illustration overlay

Histology of the colon

By the time the remnants of the food reach the colon, nearly all the nutrients have been absorbed. The major function of the large intestine or colon is the absorption of water and packaging of fecal matter. Intestinal contents move into the large intestine/colon through the ileocecal valve. Water is absorbed as the contents move from the cecum, up the ascending colon, through the transverse colon, down through the descending colon and sigmoidal colon. The result is that the contents transition from very watery (cecum) to semi-solid (descending colon). The mucosa of the colon has tremendous numbers of goblet cells, which are unicellular exocrine glands that secrete mucus (Figure 11). This abundant mucus secretion helps to lubricate passage of stool/fecal matter through the colon.

Because its contents can be semi-solid or solid, the colon must also be able to move its contents with more force. As a result, the muscularis externa layer of the colon is very thick.

Figure 11: Mucosa of the colon with and without illustration overlay

Chapter Illustrations By:

Georgios Kallifatidis, Ph.D.

Soma Mukhopadhyay, Ph.D.