Respiratory System

The respiratory system is responsible for ventilation (moving air into and out of the lungs) and respiration (gas exchange or transport of O2 and CO2 into and out of the blood). The organs of the respiratory system are divided into two groups: conducting zone and respiratory zone. The conducting zone structures serve as passageways for air to move into and out of the lung. Air in the conducting zone does not participate in gas exchange. Air found in the respiratory zone structures (respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveoli) participates in gas exchange.

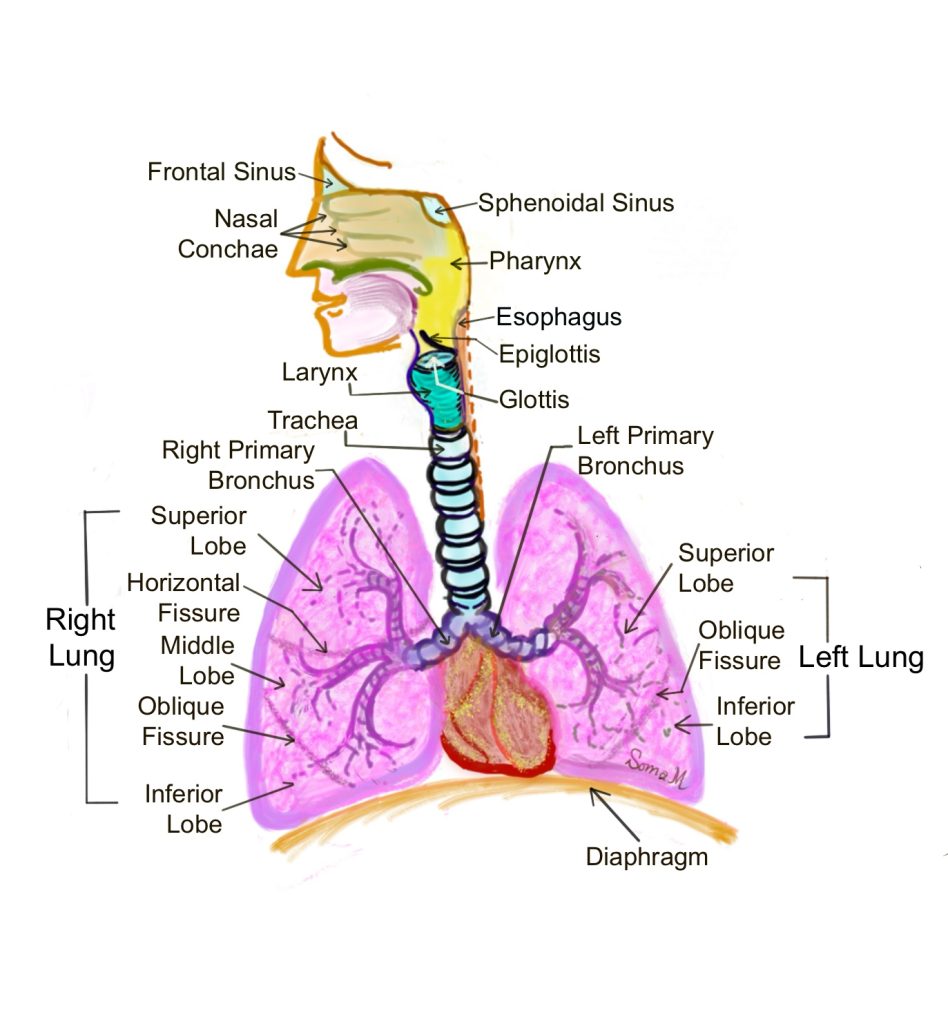

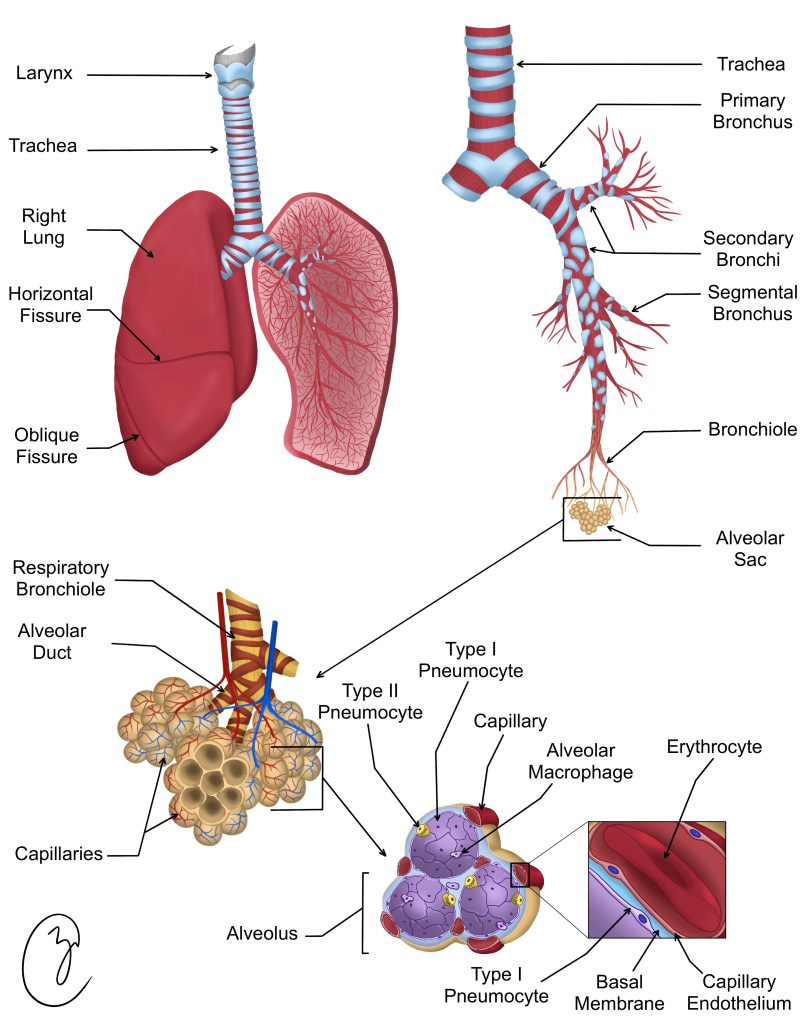

Inspired air moves from the nose or mouth posteriorly into the pharynx and then inferiorly into the larynx and trachea. The trachea bifurcates into right and left primary bronchi which enter the right and left lungs, respectively. The right lung has three lobes, which each receive their own secondary bronchus. The left lobe has two lobes, which each receive their own secondary bronchus (Figure 1). Each secondary bronchus branches into tertiary bronchi, which branch again and again into smaller and smaller bronchioles (segmental, terminal, and respiratory bronchioles).

Figure 1: Organs of the respiratory system

Several histological characteristics change as the system moves down the conducting zone into the respiratory zone. Let’s discuss these trends briefly before moving into the specific characteristics of each region:

Cartilage: Hyaline cartilage protects the respiratory system structures. Cartilage is strong but flexible, allowing us to move our body without compressing the airway. The cartilage helps ensure the airways remain patent or open, preventing collapse. The amount of cartilage surrounding the structure decreases as the system moves down the conducting zone. The trachea is surrounded by c-shaped rings of cartilage. The primary bronchi have large plates of cartilage. These plates become scattered and smaller in the terminal bronchioles. The respiratory zone structures have no cartilage.

Smooth Muscle: Smooth muscle can contract to decrease airway diameter or relax to increase airway diameter. Changing the airway diameter allows the body to control flow of air into the respiratory zone structures. The amount of smooth muscle tissue increases as the system moves down the conducting zone. The respiratory zone structures have no smooth muscle.

Height of the epithelial cells: The height of the cells in the epithelium decreases as the system moves down the conducting zone and into the respiratory zone. The epithelium gradually changes from a pseudostratified epithelium in the trachea and bronchi to a cuboidal epithelium in the bronchioles, to a squamous epithelium in the alveoli.

Elastic Fibers: While we cannot see them in our micrographs, elastic fibers have the ability to stretch and recoil. The elastic fiber composition increases in the respiratory zone structures, and provides the lung the ability to recoil during expiration.

Nasal Passages

The inside of your nasal passages is lined with respiratory epithelium and the most superior part of the nasal passage is lined with sensory olfactory epithelium. These mucous-producing epithelia are ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelia (Figure 2). The mucus, produced by Bowman’s glands, and cilia help to trap particles (dust, pollen, bacteria, viruses) preventing them from reaching the respiratory zone. In the olfactory epithelium, the ciliated pseudostratified epithelium contains sensory receptor cells that relay sensory input from odor molecules to your brain by the olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I). As seen in Figure 2, the nasal passages contain hyaline cartilage, which provides structure and flexibility to the nose.

Figure 2: Nasal epithelium with and without illustration overlay

Trachea

The trachea is an open tube that extends from the pharynx inferiorly through the neck into the thoracic cavity (Figure 3). The trachea is positioned anteriorly to the esophagus and the two organs run together. The trachea is surrounded by C-shaped rings of cartilage that provide protection to the airway, while still giving us the flexibility to bend and twist our head and neck. The C-shaped rings of cartilage are positioned so that the ends of the C are pointed posteriorly. The two ends of the C are connected with a band of smooth muscle called trachealis, which contracts during coughing to help propel mucus or particulates. This flexibility helps to accommodate the expansion of the esophagus during swallowing.

Figure 3: Gross and microscopic anatomy of the respiratory system

The mucosa of the trachea contains ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium (Figure 4, green cells) anchored to a basal lamina (Figure 4, yellow layer). The cilia of the trachea are part of the ciliary escalator, which works against gravity to keep the lungs clear. The cilia of ciliary escalator work together to move mucus and any trapped particles/pathogens from the lungs superiorly so they can be expelled by coughing or moved into the digestive system by swallowing. The submucosa of the trachea contains scattered seromucous glands, which secrete mucus responsible for trapping particles or pathogens (Figure 4, top). The layer of hyaline cartilage is positioned between the submucosa and the connective tissue adventitia (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Trachea with and without illustration overlay

Bronchi and bronchioles

Left and right primary bronchi (singular, bronchus) branch off from the trachea (Figure 3 top right panel). The primary bronchi branch into secondary (lobar) bronchi, which supply the lobes of the lung. Each secondary bronchus divides into two tertiary (segmental) bronchi, which will undergo branching into smaller and smaller bronchioles.

The bronchi of the lungs contain a mucosa composed of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium (Figure 5, yellow cells). The bronchi contain smooth muscle, which is responsible for bronchoconstriction and bronchodilation to change the airway diameter (Figure 5, red cells). The bronchi contain plates of hyaline cartilage. Notice in Figure 4 that the cartilage is patchy and no longer a continuous band like that seen in the trachea.

The bronchioles of the lung contain a mucosa composed of simple cuboidal epithelium (Figure 5, yellow cells). These cuboidal cells are called club cells, and produce surfactant. Surfactant reduces surface tension caused by the layer of mucus on the apical surface of the mucosa, preventing the lung from collapsing. The bronchioles contain a thick band of smooth muscle, which is responsible for bronchoconstriction and bronchodilation to change the airway diameter (Figure 5, red cells). The bronchioles do not contain hyaline cartilage.

Figure 5: Bronchiole (top panel) and bronchus (bottom panel) with and without illustration overlay

Alveolar Sacs and Alveoli

Respiratory bronchioles branch into alveolar ducts, which terminate into alveolar sacs containing many alveoli (Figure 3 bottom left panel). The structure of the alveolar sac is similar to a big office building. In this analogy, the hallway has doors on each side that open to big rooms containing lots of tiny cubicles. Think of the respiratory bronchiole as the hallway, the alveolar duct as the doorway, the room as the alveolar sac, and the cubicles as individual alveoli (Figure 3 bottom right panel).

The bottom panel of Figure 6 shows an alveolar sac highlighted in green. Notice that the sac contains many smaller circular alveoli. The top panel of Figure 6 highlights a portion of the alveolar sac, with two alveoli shaded in tan. The wall of the alveolus is made of simple squamous epithelium, composed of type I alveolar cells (pneumocytes). The alveolar wall also contains scattered type II alveolar cells, that secrete surfactant which reduces surface tension (not shown). While we cannot distinguish them on the micrograph, each alveolus is surrounded by an elaborate network of capillaries and elastic fibers.

Figure 6: Alveolus (top panel) and alveolar sac (bottom panel) with and without illustration overlay

Chapter Illustrations By:

Soma Mukhopadhyay, Ph.D.

Juan Manuel Ramiro Diaz, Ph.D.

Zoey Collins

branching - the trachea bifurcates or branches into two primary bronchi