Thomas Peace and Conor Wilkinson

Though the Declaration of Independence and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen used the language of liberty, nowhere was the spirit of revolution made more manifest than in the French colony of Saint Domingue. Saint Domingue was the most economically productive European colony in the world. Known as the “pearl of the Antilles,” estimates suggest that it was the single largest supplier of the world’s sugar and coffee. All of this wealth was based on the labour of enslaved Africans.

Though there were free people of colour in Saint Domingue, over seven people were enslaved for every free person living in the colony. Enslavement was particularly brutal in this colony. In the six years leading up to the Revolution, nearly half of the people enslaved were newly arrived from Africa, implying that the working conditions were particularly harsh. Even for the free Black population, over the mid-eighteenth century, their own freedoms were increasingly restricted. Race, in addition to class, was becoming an even starker point of division.

The French Revolution had immediate impact in the colony. Under the Assembly, the colony gained greater autonomy and political representation in France. Reaction to the Revolution in the colony, though, was varied. Plantation owners (Grands Blancs) generally saw the Revolution as an opportunity for more autonomy and freer trade. Poor Whites (Petits Blancs) in the colony saw opportunity for common European citizenship, while free Black people (Gens de Couleur Libres) saw opportunity for equality with White society. The enslaved, however, saw in the Revolution the opportunity for abolition. We must be careful with this latter point, though, not to ascribe too much significance to the Revolutionary ideas circulating the Atlantic during the 1790s. Though they wielded influence in the Haitian Revolution, the desire to escape forced captivity is one that is intrinsic to the condition of enslavement. To think otherwise normalizes and legitimizes the practice of chattel slavery.

Violence broke out in the summer of 1791 and – over the intervening years – the Haitian Revolution took on two common goals. First, it marked a fight for the abolition of slavery. Second, it was also a struggle against European imperialism. This latter point matters a lot for understanding what happened in Haiti. With the outbreak of violence, both Britain and Spain sought to capture the island with a promise to the Grands Blancs to reinstate slavery. The Haitian Revolutionaries fought on two fronts. First, they fought for their emancipation from their enslavers, and then they fought European powers.

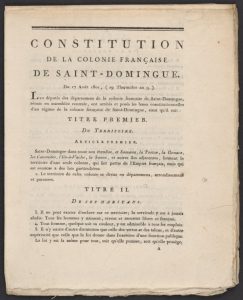

In 1801, after resisting British incursions, Toussaint L’Ouverture, the most prominent leader of the Revolution, issued Haiti’s first constitution. France, now under Napoleon Bonaparte, retaliated by sending significant numbers of troops and secretly working to restore the island’s system of African enslavement. L’Ouverture was arrested and sent to France. Violence continued for another two years before the Haitians successfully removed European influence.

In this module, you will read L’Ouverture’s 1801 constitution. As you read this document, consider the following questions:

- Compare this document to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen.

- Where are the similarities?

- In what ways is it different?

- What is the relationship envisioned between Haiti and France?

This module was modified in October 2022.