12 20th Century on

In the next phase of Native American history, the government took yet another approach to relations with Native Americans. This shift was likely a response to Native participation during World War I (Treuer, 2019). First came the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 which officially recognized Native Americans as citizens, even though legally, under the 14th amendment, native peoples already had birthright citizenship. However, some states continued to withhold voting and other rights from native individuals. For example, Arizona did not allow native peoples to vote until after WWII in 1948 (Arizona Historical Society, 2020). This was a great irony as many Navajo Codetalkers had served as crucial military personnel. By using knowledge of their native language as a code that was never broken, they definitively helped win the Pacific front for the Allies.

Next was the Meriam Report, a comprehensive evaluation of Native reservation conditions, hospitals, schools, and other agencies was published in 1928 by the Brooking Institution. The push for the report came from Native American advocates that wished to publicly identify the failures of Native American policies and possibilities for progress. Men such as Peter Graves and John Collier called out the policy issues of the Dawes Act as well as the denial of religious freedoms that natives had endured.

Progress during the 1930s was difficult, especially during the economic crisis of the Great Depression. Nevertheless, Collier was able to negotiate the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, sometimes also called the Indian New Deal, because it was passed under President Roosevelt and his New Deal agenda. Introduced by Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier, the act encouraged rejuvenation of native practices, but under a single policy applied to very diverse groups of native peoples. This act allowed for Native American lands to remain in their control and distributed amongst tribal members as well as the ability to self-govern. However, it only allowed for tribal governments under federal rules and formatting, which did not reflect how groups traditionally had or would like to govern themselves. The Indian New Deal also made changes to Indian Education by establishing reservation day schools, instituted Indian Health Services and established the Indian Arts & Crafts board. Although this was a step towards granting of freedoms, the IRA was problematic within Indian reservations for its ambiguities and generalizations.

The National Congress of American Indians was started in 1944 by natives in response to these U.S. policies. This pan-Indian group of representatives offered a way for native voices to be heard in Washington, D.C.

Then, in 1956, the government took a different tactic in the implementation of the Indian Relocation Act. This legislation was passed to encourage young American Indians to leave reservations for urban areas to further the assimilation into American society. The BIA started its Urban Relocation Program relocating reservation families to urban centers. Financial assistance, vocational training, and other support was guaranteed for those that took up the opportunity. The result was often disastrous because the support that was guaranteed under this legislation was not consistently fulfilled. Many suffered from culture shock, homelessness, and poverty due to the failures of the policy.

During the mid-20th-century, the U.S. sought to end its relationship with certain, but not all, Indian groups. They wished to dismantle tribal governments, dissolve tribal land holdings and end federal services to natives. Compensation for treaty provisions never paid was intended. Yet, it also meant the termination of federal services. The nation no longer wanted to be a guardian in trust. It hoped to do this by eliminating reservations and letting natives be subject to state laws/taxes.

While this era improved the lives of Native Americans to some degree, Native Americans still endured racial discrimination and hardships due to decades of mistreatment in America. The civil rights movements of the 1960s inspired many groups to push for equality

Amongst the increasing clamor for civil rights, there arose the Red Power Movement. The movement was led by mostly young American Indians that sought policies to bring aid to Native American communities, maintain and protect land ownership, and reverse the termination of tribal recognition. Taking the cue of the African American protests of the time, participants of the Red Power movement engaged in non-violent protests and demonstrations to bring attention to their cause and wish to reclaim native sovereignty. Additionally, as part of the bigger drive for Red Power, the American Indian Movement (AIM) group was founded in 1968. The supporters of AIM were largely the results of the failures of relocation. It was a way for diverse Native Americans to come together in cities and form regional pan-Indian groups. Learn more about the American Indian Movement from primary sources housed at the Digital Public Library of America’s website.

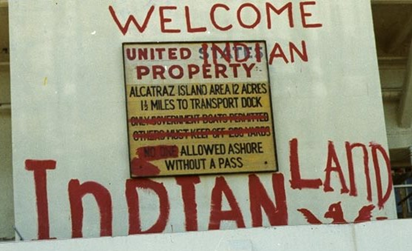

In November of 1969, AIM and other supporters carried out a 19-month long Occupation of Alcatraz. The federal facility lay dormant since 1963, and in a symbolic protest, Native American protesters made landfall on the island, claiming the land theirs for the taking, much like the European colonizers of the distant past. Occupants and supporters felt that reclaiming federal land from the government sent a clear message to the American public. For months, numerous Natives occupied the island, contacting the mainland primarily through a supply ship that would ferry people and supplies back and forth during occupation. Eventually the occupation ended with the government forcing their removal, but the movement caught the brief attention of the media lending sympathy towards their cause. To this day, the graffiti on walls and structures painted by the occupants is still present.

“Alcatraz Occupation Welcome to Indian Land graffiti” by Wikimedia is in the Public Domain, CC0

APPLICATION 3.3

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVE: ALCATRAZ PROCLAMATION

Goal

To examine a Native American protest statement during the 1960s.

Instructions

Read the Alcatraz Proclamation. Answer the following questions:

- What is the tone of the Proclamation?

- How does the speaker define “Indian Reservation”?

- Were the actions of the Native American occupiers illegal, or justified?

This activism and new awareness is also known as the Self-Determination Era. President Richard Nixon starts the move away from a federal role as a paternalistic guardian and wishes to halt extreme native dependence on the federal government. It was about finding a way for native autonomy without completely cutting federal support and services. This time Indians were to have a role/say in matters and could publicly fight to maintain their heritage while also participating in the dominant society. Some important acts and organizations gave back some rights that had been previously suppressed, like having a say in where you child lived and with whom, what religious practices you kept and more. You can click on the following links to learn more about the:

- Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) 1978

- American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) 1978

- Native American Rights Fund

- Tribal College Systems

1968 saw the establishment of the first tribal college in the nation, the Navajo Community College (now Diné College). The Indian Education Act of 1972 granted funds to increase graduation rates, curricular issues, and support services for Native Americans. It opened more avenues for native peoples to formally advocate for and educate their children in their own educational systems. These policies continued to expand, exemplified in Some schools even began to implement lessons on Native American culture and history.

Beginning in the 1980s, the pseudo-reparations that Native Americans were awarded by the government came in the form of Indian Gaming operations. In a landmark case, California v. Cabazon, the Cabazon and Morongo Mission Indians won the right to run gaming facilities on tribal lands. After this ruling, gambling operations arose in other reservation lands across the nation. The late 80s witnessed legislation to tax and regulate Indian gaming, but otherwise, these establishments allowed tribes to generate wealth for their communities. Profits and distribution of profits vary from tribe to tribe.

The 21st century is a time of Native Nations within a Nation. The U.S. has a continuing trust relationship with federally recognized tribes. In most cases, the federal government continues to act paternally as the “Great White Father” towards Native Americans. Still, some key acts and organizations have been added as avenues towards increasing recognition of native equity and sovereignty, such as the:

- Native American Grave Protection & Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) 1990

- National Museum of the American Indian 2004

- Embassy of Tribal Nations 2009

- Claims Resolution Act 2010

- Tribal Law and Order Act 2010

More and more cultural awareness about these long-time inhabitants of the Americas has been occurring. The myth of Columbus and his “discovery” is not as commonly upheld. The violence and political policies of the 19th and early 20th centuries are included in some historical narratives. Indigenous Day has been added to the calendar, native cultures are alive and continue, and some stereotypes of Native Americans are disappearing from logos and mascots. However, there is still much progress to be made.

Today, there are 574 federally recognized Indian tribes and 325 reservations in the United States. The 2020 Census shows that Native American and Alaska Native populations “increased from 5.2 million in 2010 to 9.7 million in 2020, a 86.5 percent increase;” in addition, Native Hawaiians count in at 1.6 million (Indian Country Today). First peoples live, work, dance, create, and more in all parts of our nation. They are here and alive!

Chief Joseph, a leader of the Nez Perce once said, “Good words do not last long unless they amount to something.” Native Americans still have low numbers of representation in higher education, and an average low median income compared to other racial and ethnic groups. COVID-19 also severely impacted reservation communities. And yet, many native traditions that survived despite more than two generations of U.S. policies of acculturation that forbade tribal arts, languages, and ceremonies. The elders have worked hard to keep the embers of their culture burning today.

APPLICATION 3.4

OUR FIRES STILL BURN

Goal

To develop knowledge and appreciation for indigenous people and the intrinsic relationship between social movements and social change.

Instructions

- Read the film review of Our Fires Still Burn: The Native American Experience.

- Watch the film Our Fire Still Burn: The Native American Experience: The Native American Experience Dance Performance, Film Screening, and Panel Discussion.

In preparation for class discussion, answer the following questions:

- In what ways do you think the loss of Native American culture has directly or indirectly contributed to the current social issues and conditions in Native Nations (ex. diabetes, heart disease, suicide rates, and addiction)? Discuss actions Native people are taking today to reverse the effects of this cultural loss?

- A section of the film examines the economic changes that were brought to the Isabella Indian Reservation by introducing casinos and Indian Gaming. The pros and cons of this subject are debated across Native Nations. Explore and discuss what you think the pros and cons are.

- Levi Rickert says it is important for Native Americans to tell their own stories since their history and stories are important to all individuals. As a class we will conduct our own oral history project. Use their phone recorder or computer to interview a family member and gather a story. Then write a short response paper on what you learned and how it your own understanding or perspective about your family, culture, community, or racial-ethnic group.

Source

Adapted from Lee, J. (2014). Our fires still burn: The Native American experience viewer discussion guide. Vision Maker Media funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. https://visionmakermedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/edu_vdg_ofsb.pdf target=”_blank”