11 United States & its “Indian Problem”

United States Indian Policies were based on English ideas of dealing with first peoples by removing them from living near European settlers or having them eliminated. Phillip Schuyler and George Washington were architects of a gradualism approach where slowly natives are convinced to move to separate Indian Territory in the west and the government established a central department to deal with native peoples.

From the beginning of America as a nation, there was the idea of a single permanent homeland known as “Indian Country.” It would be an area exclusively for native groups that was closed to white settlement and located west of the Mississippi River.

Watch the The Invasion of America video (1 minute) to see how the concept of Indian Territory changed over time.

Most of the 19th century was a time of great turmoil and despair for Native Americans. The U.S. government approached relations with Natives in two different ways, first removal and relocation; then land redistribution and assimilation.

The American government repeatedly reneged on treaties, and new states formed as populations expanded. When U.S. citizenship was established, Native Americans were not extended the rights of other White Americans, not until the 20th century.

And so, native groups have functioned in two different modes over the course of American history: by resistance to power and attempts to work within the framework of the U.S. government.

19th century Indian Policies

The Office of Indian Affairs was established in the War Department in 1824 as a separate entity to deal with Indians. In 1832, it was renamed the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). In 1849, it was moved to the Department of the Interior – which also includes the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and more. No other division in the Interior deals with humans. In 2021, the first Native American Secretary of the Interior – Deb Haaland – a tribal member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico was appointed.

Removal & Relocation

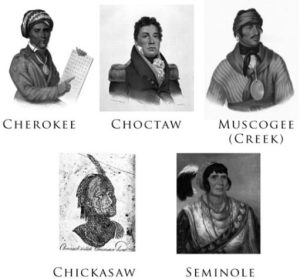

Between the 1820s up through the 1880s, Native Americans were continually uprooted and relocated to reservation lands. These actions were legitimized by the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, under President Andrew Jackson. This act passed with President Jackson’s approval and was later carried out under his predecessor Martin Van Buren. President Jackson claimed that Native Americans were “uncontrolled possessors” of their lands, and therefore would only be allowed to occupy lands that were given to them by their conquerors (Jackson, 1829; Richter, 2001). The act allowed led to the initial removal of five different tribes from their ancestral lands to relocate to reservation territory in modern day Oklahoma. The former lands would later be settled by White Americans.

In a shift of tactics, instead of using force to combat the removal process, one of the five tribes, the Cherokee, sought to work within the U.S. legal system to sue for their rights to their land. This was an uphill battle, especially after Georgians discovered gold in Cherokee territory in 1829, making their territory highly coveted. After tumultuous court battles, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court upheld Cherokee rights to their lands. Unfortunately, even this court ruling was not enough to protect the tribes, and over the course of several years, the five tribes: Chicksaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, and the Cherokee were forced from their homelands to a territory west of the Mississippi River. The removal process took several years and was later named the Trail of Tears. The reason for the name was because the relocated Natives took the forced journey on foot, many of them dying of exposure, disease, and starvation. Men, women, children, the elderly, the infirm – they were all forced to walk with their possessions, no wagons, no horses, tents, or provisions. One in three died on the journey, and they barely made it to their destination. This was the first of many multiple involuntary, forced removals of native groups all over the US that happened through the end of the 19th century.

APPLICATION 3.2

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVE: CHEROKEE INDIANS

Goal

To understand the experiences of the Cherokee Indians in protesting Indian Removal policies.

Instructions

Read the Cherokee Petition Protesting Removal, 1836. Answer the following questions:

- What reasons does the speaker use to protest removal?

- What kinds of language does the speaker use to describe U.S. policies?

The interactions between the Americans and Native Americans during the 19th century were justified by a concept that was coined into words by John O’Sullivan in the 1840s – Manifest Destiny. O’Sullivan successfully illustrated a concept that was already ingrained in the minds Americans since the initial settlement of this country. Manifest destiny was the belief that Americans had a destiny, a calling that could not be changed. That destiny was to inhabit the lands of North America from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast. Additionally, O’Sullivan was clear that this “destiny” was dictated by God, underpinning this concept with the most prevalent religion in America of the time, Protestant Christianity. By giving this concept a name, O’Sullivan gave Americans a justification to continue to settle and occupy all the lands in North America, continually pushing westward no matter what was in their way because it was their destiny. What he really conceptualized were the beliefs and desires of even the earliest colonists, who had journeyed west across the Atlantic Ocean so long before him. In this era, Manifest Destiny was not merely about colonial settlement, but American domination of land, resources, and societal order.

The fact is removal of First Peoples happened for most of the 19th century, with hundreds of thousands people relocated forcibly as Manifest Destiny remained a policy of the federal government. One of the last relocations (which was ultimately unsuccessful) was of the Diné – or Navajo – people in the Southwest US started in 1863 and was led by Kit Carson. The Long Walk, wherein thousands perished on their way to far southeastern New Mexico reservation lands far from their traditional Arizona & Utah homelands. Any tribal members that resisted were shot.

Amidst the American civil war as the country was torn by armed conflict, American citizens kept a steady pace on their quest for westward expansion. In what is Minnesota today, the Dakota tribes fought for their rights to remain in control of their lands in a conflict called the Dakota (Sioux) Uprising of 1862. Because of the severe depletion of buffalo herds, which was the tribe’s main food source, the Dakota tribes resorted to farming, which was not working out well. The tribes were then forced to resort to asking the state government for aid, or buying food on credit, or else their people would starve. Local authorities refused to comply and tensions rose. A group of Dakota men killed five White settlers, and violence continued to escalate into war with the Dakotas. By the time local militias ended the violence, hundreds of Dakotas were taken prisoners and held accountable in courts of local authorities where murder, rape, and atrocities took place. Officially, 303 Dakota tribal members were sentenced to be hanged, until President Lincoln stepped in and commuted most of the sentences to 38 individuals. This was the largest mass execution by hanging in U.S. history. The remaining members of the local Dakota tribes were chased into the hills, hunted, killed, and starved out.

After the events of the Dakota Uprising, more and more violent incursions occurred. In 1864, the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes attempted to protect their lands in Colorado. However, when gold was discovered on their lands, Americans sought to gain access. The tribes sought peace negotiations, but Colorado militiamen forged a different path. In a violent attack called the Sand Creek Massacre, a White militia openly attacked the tribes at Sand Creek, killing over 200, forcing those survivors onto reservations.

Treaty Making 1832-1871

Under Supreme Court rulings by John C. Marshall, American Indian nations were considered to have sovereignty rights so they could sign treaties. They were also seen as Domestic Dependent Nations in that: They occupy a territory to which we assert a title independent of their will, which must take effect in point of possession when their right of possession ceases; meanwhile, they are in a state of pupilage. Their relations to the United States resemble that of a ward to his guardian.” (Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia 1831). 52 treaties alone were signed between 1853-1856. The U.S. government signed a total of more than 370 treaties.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, U.S. Policies switched to a plan for multiple small Indian Reservations to bring natives under federal control and work to assimilate them into the dominant culture. From 1867-1887, the greatest number of reservations were created.

Allotment

Driven by a so-called campaign of peace, President Ulysses Grant attempted a different approach, closing this era of removal and relocation. In a post-war effort, Grant instituted a ‘Peace Plan’ to “conquer through kindness.” This plan was called the Dawes General Allotment Act or the Dawes Act of 1887. The goal falsely presented as a plan to redistribute and protect land rights but turned out to be another process of denial of land rights. The Dawes Act revoked collective land ownership from the tribes and redistributed the land in smaller plots to individuals within the tribes. Reservations were broken up in 160 acre parcels and allotted to heads of Native American families in hopes of turning them into self-sufficient farmers. After allotment, “surplus” lands were distributed to non-natives. Tribal members would be given the deed to those plots of land after they had lived on and “improved” that land for 25 years. Only after the 25 years of probation would the individuals receive the land titles, and some would even be granted citizenship.

This legislation had multiple issues. First, it denied the traditional communal land use that generally most Native American groups had practiced. Customarily, no individual owned land, but they utilized it as a collective unit.

Second, it assumed that native individuals were not capable of holding a land deed. This part of the act was intended to defend Natives from criminal land prospectors or sneaky investors, but it also assumed that a native person was too inexperienced and unintelligent to recognize unfair deals.

A lot of land was determined to be “surplus” and taken during the Allotment Era and was released by the government to non-native – instead of native – citizens The law withheld land titles for the span of a generation on purpose. It was written so that the lands could be awarded – or forfeited by non-occupancy – to the next generation of native children. These would be children that had most likely gone through – or were forcibly away at – Indian boarding schools. Indian boarding schools were meant to Americanize or assimilate Native American children into American culture through education.

Boarding Schools

Native American education in the U.S. during the 19th century was similar to other marginalized groups such as immigrant communities. For Native Americans, the outcome was much more detrimental to the culture. Education for these groups was tailored towards one goal – assimilation into American culture, also known as Americanization.

From 1850s-1978, native children were removed from their family homes and educated in boarding and day schools in order to assimilate them as “Americans.” Army Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s philosophy was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” He developed a program of education for the Americanization of natives. He opened the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879.

The process of deemphasizing the original cultures of native individuals was intended to indoctrinate students and teach them what was generally acceptable in American culture. For example, language was a prevailing tactic to shift children towards the dominant culture by forcing children to speak English rather than their Native language. For children of new immigrants, this was problematic but practical, for they could remain bilingual, speaking one language at school and another at home. For Native Americans, this was cultural erasure, for they were removed from their families and the children were unable to learn their native language.

Through the Americanization process, Native American groups’ cultures and customs were impacted. Adult tribal members with language and cultural knowledge were not in frequent contact with their own children. Native adults were also continually being eradicated through violent encounters with the US and its settlers. By removing children from their homes and traditional cultures, they were not taught or able to become fluent in their native language. Traditional knowledge was not – or could not be – passed on.

Ultimately, the U.S. government operated over 100 boarding schools for Native American children taken from their homes.

The 19th century was extremely damaging to Native Americans – due to the breaking of treaties, erasure of culture, and outright genocide. The future of Native Americans was uncertain, and the next century would prove to be just as tumultuous.