105

Henry David Thoreau sought to live an essentialist life, one devoid of the unnatural excrescences loaded upon individuals by society and societal institutions. By realizing self-unity and being true to his individual self, he sought to realize his true selfhood as an organically-rendered microcosm of the macrocosm that is the world in nature. For Thoreau, nature has subjective value and meaning and shapes not only the body but also the mind and spirit. When such external institutions as the church and the government divert the individual from the overarching unity of themselves and nature, then Thoreau thought the individual should prefer integrity over conformity.

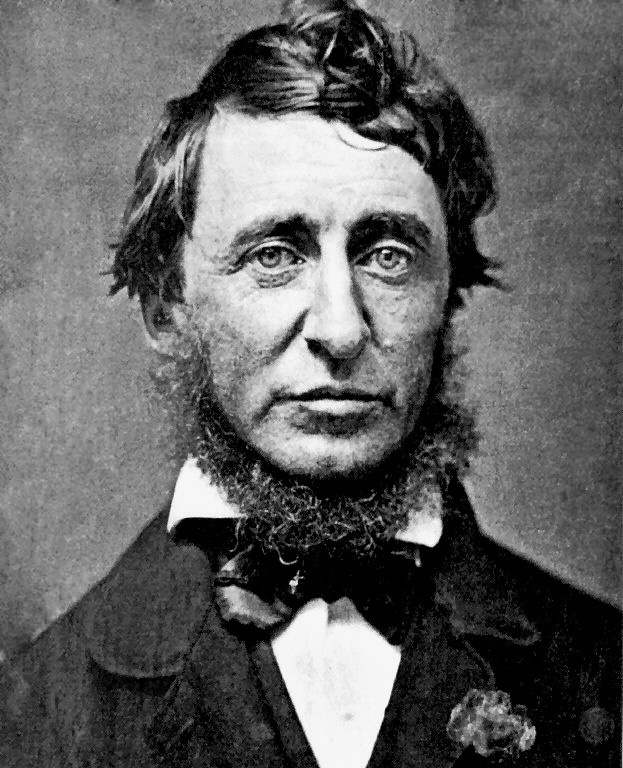

Figure 1. Henry David Thoreau, 1856

Thoreau distills philosophical thought—such as Transcendentalism—and objective, sensory, scientific collection of concrete facts—such as Darwin claimed as his methodology—into a unique expression of integration: of self with nature, of self with culture, of culture with nature. He expressed these views both lyrically and plainly in the two books published during his lifetime—A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1848) and Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854)—in the lectures he gave from Boston to Bangor, Maine; in his published essays, including “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849) (later retitled “Civil Disobedience”); and in the personal journals he started at Emerson’s urging, kept throughout his life, and that filled twenty volumes when published after his death. The actions of his life, though not apparently earth-shaking, reflect Thoreau’s self-integrity. He was born in Concord, Massachusetts, to John Thoreau and Cynthia Dunbar. His father made a meager living as a store-keeper before manufacturing lead pencils. Thoreau and his brother John attended the Concord Academy. Thoreau’s devotion to reading made him the strongest family candidate for study at Harvard. He was enrolled there in 1833 and graduated in 1837. He then returned to Concord and taught briefly at an elementary school, from which he resigned when the school board ordered him to flog students. In 1838, he took a position as teacher and administrator at Concord Academy. In 1839, his brother joined him as teacher and co-director. That same year, he and John took a two- week boating trip. In 1841, he left the Academy with his brother due to John’s poor health, with John dying of lockjaw on January 1, 1842.

Thoreau had met Emerson in 1836, heard Emerson’s lecture “The American Scholar,” and began to lecture himself. He later attended Bronson Alcott’s intellectual “conversations” and became involved in the Transcendental Club. Thoreau published poems and essays in The Dial, the journal sponsored by that club. When he lived at his parents’ home in Concord, Thoreau assisted at his father’s pencil factory. He also worked as a surveyor. When he lived at Emerson’s home, he did handyman chores. When he lived with Emerson’s brother William at Staten Island, he tutored the family’s son. In 1844, he burned around 300 acres when he accidentally set fire to Concord woods. On July 4, 1845, he moved into a cabin that he built on Emerson’s land at Walden Pond, near the Concord woods. He lived there two years, two months, and two days. During that time, he spent one night in the Concord jail on July 23, 1846, for refusing to pay a poll tax that would support a government that sanctioned slavery and waged a pro-slavery war in Mexico.

In 1848, he published at his own expense A Week on the Concord and the Merrimack Rivers, a hybrid-genre book recording his boat trip with his brother which included poetry, nature observations, personal meditations, and scripture. It sold 306 of its 1000 copies and received little public notice. He attended anti- slavery conventions and published articles against slavery, including “Slavery in Massachusetts” in 1854. That same year, he published Walden. In it, he explains his reason for going to the woods:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discovery that I had not lived.

Thoreau publicly supported John Brown’s anti-slavery attack on Harper’s Ferry, publishing “A Plea for John Brown” in 1859. He explored forests in Maine and made walking tours in Massachusetts and Canada. He suffered from tuberculosis for six years before he died in 1862. Several of his works were published posthumously by his friends, including The Maine Woods (1864), Cape Cod (1865), and A Yankee in Canada, Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers (1866). His journals were published in chronological order in 1906.

He did not, as Oscar Wilde would say of himself, put his art into his life. But he did make his life his art. His writing style is marked by wit, puns, allusions, metaphors, and symbols; its content comprehended social issues like slavery, economy, politics, and nature. Its impact still continues. Both Mahatma Ghandi, supporting Indian independence from England, and Martin Luther King Jr., supporting black civil rights in America, modeled their activism on Thoreau’s “Resistance to Civil Government.” Thoreau’s observations of nature and man’s place in and impact on nature inspired environmentalists like John Muir. His writing realizes art’s ability to enlighten and inspire and to link the dead with the living.

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Henry David Thoreau, 1856,” Benjamin D. Maxham, Wikimedia, Public Domain.