157

Like his contemporary Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wedded sound and sense in epical poetry on the nation’s lore and history. Unlike Tennyson, Longfellow drew not upon Arthurian legend but upon American stories and legends. He wrote about Native American lives, particularly that of the Ojibwe in The Song of Hiawatha (1855) and the Plymouth Colony in The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858). The metrical facility, flexible rhyming, and romantic characterizations in Longfellow’s poetry made his work immensely popular with readers in both America and England. However, he was dismissed by later generations for a time as overly traditional and didactic. Now, readers appreciate the nuance and diversity, wide-ranging scholarship, and linguistic knowledge available in Longfellow’s work. With T.S. Eliot, Longfellow is the only American poet memorialized at Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner.

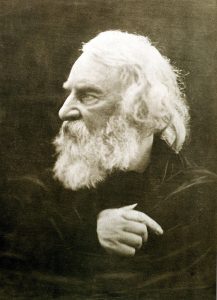

Figure 1. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Born in Maine, Longfellow studied there, first at Portland Academy then at Bowdoin College, where Nathaniel Hawthorne and Franklin Pierce were among his classmates. Upon graduation, he was offered a professorship of modern languages at Bowdoin. To prepare for this position, Longfellow traveled to Europe, visiting France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and England. Longfellow translated from the original the texts he taught at Bowdoin, to the neglect of his own creative work. In 1831, he married Mary Storer Potter (1812–1835) and published prose travel pieces in The New-England Magazine. From 1835 to 1836, he once more traveled abroad to prepare for another teaching position, at Harvard University, for which he acquired a greater knowledge of Germanic and Scandinavian languages. While in Holland, his wife miscarried and died. While touring Austria and Switzerland, he met Fanny Appleton, the woman he would marry seven years later.

In 1839, he published Voices of the Night, his first book of poetry. He followed it with Ballads and Other Poems (1841), Poems on Slavery (1842), and a collection of travel sketches in prose entitled The Belfry of Bruges and Other Poems (1846). As noted in his May 30 diary entry, this latter collection traces its inspiration as well as its artful execution to sound, to the perfect blending of sound and sense:

[T]hose chimes, those chimes! How deliciously they lull one to sleep! The little bells, with their clear, liquid notes, like the voices of boys in a choir, and the solemn bass of the great bell tolling in, like the voice of a friar!

Residing at Craigie House in Cambridge—a wedding gift from his wealthy, industrialist father-in-law—Longfellow became a leading literary figure in not only New England but also across the nation. He consolidated this position by leaving academic life in 1854 to devote himself entirely to writing. In 1861, Fanny Appleton Longfellow was burned to death after her dress caught fire; subsequently, Longfellow’s cosmopolitan and religious interests came to the fore in such works as a three-volume translation in unrhymed triplets of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1865–1871) and Christus: A Mystery, published in three parts (1872).

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,” Julia Margaret Cameron, Wikimedia, Public Domain.