8

Wendy Kurant

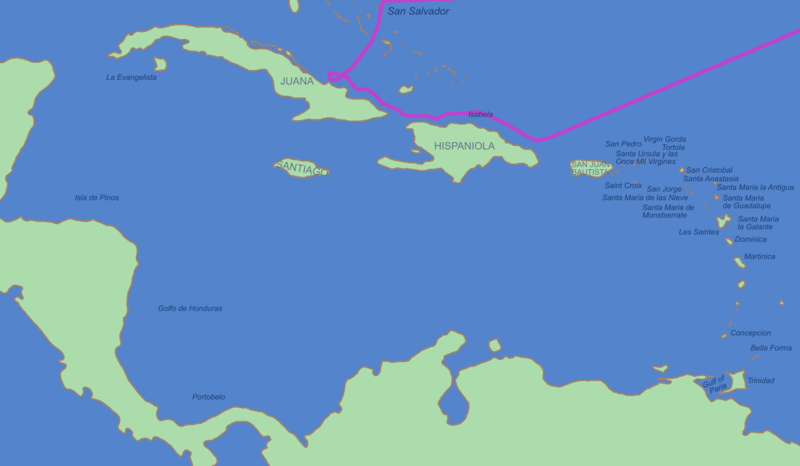

A sailor from his youth, Christopher Columbus sought to discover a mercantile route to Asia via the Atlantic Ocean, a route he calculated as only 3,000 miles across the Atlantic. Winning support in 1492 from Ferdinand and Isabella, monarchs of Spain, Columbus embarked on his historic voyage that failed to discover the route to Asia but instead discovered the New World, where he first landed at what is now the Bahamas. After that voyage with three caravels, Columbus returned to the New World three more times in 1494, 1496, and 1500, founding settlements at Hispaniola and the West Indies and exploring parts of Central and South America.

Figure 1. “Portrait Believed to be of Christopher Columbus”

Columbus compensated for his original mission’s failure by taking possession of these new lands and the people he first encountered there—people Columbus significantly noted as wearing gold adornments. Although he hoped to bring peace with him to what he described as paradisiacal landscapes, Columbus’s first settlement at Hispaniola, “Villa de la Navidad,” proved too grounded in the earthly desires and ambitions of the Old World. The first settlers demanded riches and women from the Native Americans and were in turn massacred. The second settlement, governed by Columbus’s brothers, fell into such disorder that Columbus was forced to return to Spain to defend his own activities. Upon his later return to Hispaniola, Columbus had to defend his authority over the settlers and claim authority over the Native Americans, whom he enslaved as laborers and searchers for gold.

Figure 2. “Map of Columbus’s First Voyage”

In 1500, Columbus returned once more to Spain to defend his reputation and then sought to secure his reputation and fortunes in the New World through further explorations there. This foray into what is now Panama and Jamaica led to disaster, both physical (in a shipwreck) and emotional (in a breakdown). Columbus made his final return to Europe where he died in 1506.

His 1493 Letter of Discovery derives from Columbus’s manuscripts, was translated into Latin by Aliander de Cosco, and was printed by Stephan Plannck. It is addressed to Lord Raphael Sanchez, treasurer to Ferdinand and Isabella, who clearly determines the rhetorical approaches Columbus makes in this letter. It describes the New World in terms amenable to his patrons’ desires and ambitions but detrimental to the people he mistakenly named Indians.

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Portrait Believed to be of Christopher Columbus” by artist unknown, Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Figure 2. “Map of Columbus’s First Voyage,” by unknown, from Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA 3.0.