178

Born into an influential and socially prominent New England family in 1830, Emily Dickinson benefited from a level of education and mobility that most of her contemporaries, female and male, could not comprehend. The middle child of Edward Dickinson and Emily Norcross, Dickinson, along with her older brother Austin and younger sister Lavinia, received both an extensive formal education and the informal education that came by way of countless visitors to the family homestead during Edward Dickinson’s political career. Contrary to popular depictions of her life, Dickinson did travel outside of Amherst but ultimately chose to remain at home in the close company of family and friends. An intensely private person, Dickinson exerted almost singular control over the distribution of her poetry during her lifetime. That control, coupled with early portrayals of her as reclusive, has led many readers to assume that Dickinson was a fragile and timid figure whose formal, mysterious, concise, and clever poetry revealed the mind of a writer trapped in the rigid gender confines of the nineteenth century. More recent scholarship demonstrates not only the fallacy of Dickinson’s depiction as the ghostly “Belle of Amherst,” but also reveals the technical complexity of her poetry that predates the Modernism of T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and Marianne Moore by almost three- quarters of a century. In the selections that follow, Dickinson’s poetry displays both her technical proficiency and her embrace of techniques that were new to the nineteenth century. Like her contemporary Walt Whitman, Dickinson used poetry to show her readers familiar landscapes from a fresh perspective.

Figure 1. Emily Dickinson

The selections that follow, from Dickinson’s most prolific years (1861-1865), illustrate the poet’s mastery of the lyric—a short poem that often expresses a single theme such as the speaker’s mood or feeling. “I taste a liquor never brewed –”… celebrates the poet’s relationship to the natural world in both its wordplay (note the use of liquor in line one to indicate both an alcoholic beverage in the first stanza and a rich nectar in the third) and its natural imagery. Here, as in many of her poems, Dickinson’s vibrant language demonstrates a vital spark in contrast to her reclusive image. . . . “The Soul selects her own Society –,” shows Dickinson using well-known images of power and authority to celebrate the independence of the soul in the face of expectations. In both of these first two poems, readers will note the celebrations of the individual will that engages fully with life without becoming either intoxicated or enslaved. . . . “Because I could not stop for Death –,” one of the most famous poems in the Dickinson canon, forms an important bookend to “The Soul” in that both poems show Dickinson’s precise control over the speaker’s relationship to not only the natural world but also the divine. While death cannot be avoided, neither is it to be feared; the speaker of this poem reminds readers that the omnipresence of death does not mean that death is immanent. This idea of death as always present and potential comes full circle in . . . “My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –.” Here Dickinson plays with our preconceptions not only of death, but also of energy which appears always to be waiting for someone to unleash it. Considered carefully, these four poems demonstrate the range of Dickinson’s reach as a poet. In these lyrics, mortality and desire combine in precise lyrics that awaken both our imagination and our awareness of the natural world.

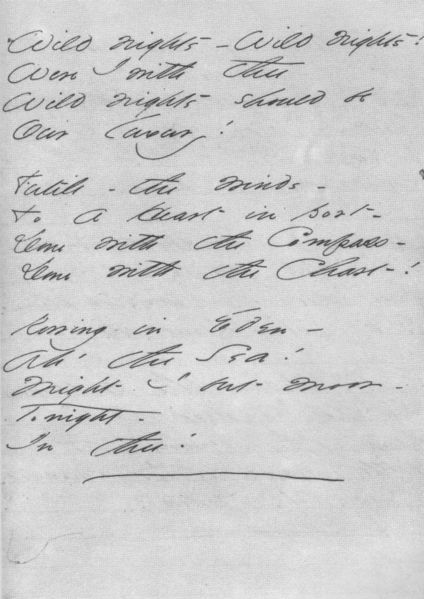

Figure 2. Wild Nights, Manuscript

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Emily Dickinson,” Unknown Author of Derivative Work, Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Figure 2. “Wild Nights, Manuscript,” Emily Dickinson, Wikimedia, Public Domain.