35

Wendy Kurant

Mary Rowlandson (née White) was born in Somersetshire, England around 1637. Two years later, her family joined the Puritan migration to America and settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. They then lived in Salem, Massachusetts, before moving to Lancaster, a frontier settlement comprising of fifty families and six garrisons. In 1656, she married Joseph Rowlandson (1631–1678) who became an ordained minister. They had four children, one of whom died in infancy.

In 1676, Lancaster was attacked in the ongoing conflict now known as King Philip’s War (1675–1678). Metacomet (1638–1676), called King Philip by the Puritans, was chief of the Wampanoags. His father, Massasoit (1580–1661), signed a treaty with the Pilgrims at Plymouth in 1621. By 1675, white settlers were pushing Native Americans from their land to such a degree that Algonquian tribes formed a coalition and raided white settlements. Among these was Lancaster, where Rowlandson’s garrison was attacked and burned. She, along with twenty-three other survivors, was taken prisoner by the Native Americans.

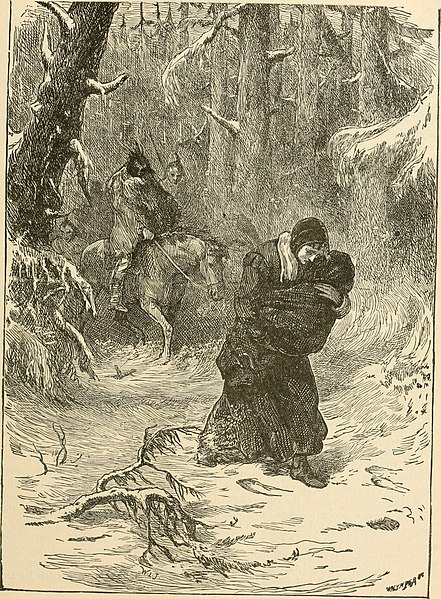

Figure 1. The Capture of Mary Rowlandson

Her captivity lasted eleven weeks and five days, during which time the Algonquians walked up to Chesterfield, New Hampshire and back to Princeton, Massachusetts. There, Rowlandson was ransomed for twenty pounds in goods. In 1677, her family— including the surviving children taken captive along with Rowlandson—moved to Wethersfield, Connecticut where Joseph Rowlandson had acquired a position as minister. He died in 1678; one year later, Rowlandson married Captain Samuel Talcott. She remained in Connecticut, where she died in 1711.

Soon after her release from captivity and before her first husband died, Rowlandson began to write of her experiences with the Native Americans. Published in 1682, her memoir became immensely popular as a captivity narrative, a popular genre in the seventeenth century. These captivity narratives record stories of individuals who are captured by people considered as uncivilized enemies, opposed to a Puritan way of life.

Much of their popularity stemmed from their testimony of the Puritan God’s providence. Rowlandson’s narrative adheres to Puritan covenantal obligations, alludes to pertinent Biblical exemplum, and finds God’s chastising and loving hand in her suffering and ultimate redemption. Her suffering includes fear, hunger, and witnessing the deaths of other captives. She describes the Native Americans as savage and hellish scourges of God. She acclaims the wonder of God’s power when these same Native Americans offer her food, help her find shelter, and provide her with a Bible. Her rhetorical strategies and the ambivalences and ambiguities in her account—particularly in regards to cultural assimilation, cross-cultural contact, and gender issues of social construction of identity, voice, and authority—contribute to its continuing popularity to this day.

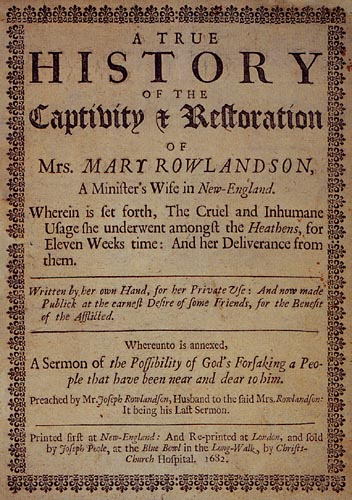

Figure 2. The Captivity & Restoration of Mary Rowlandson, Title Page

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “The Capture of Mary Rowlandson,” Henry Northrop, Wikimedia, Likely Public Domain.

Figure 2. “The Captivity & Restoration of Mary Rowlandson, Title Page,” Mary Rowlandson, Wikimedia, Public Domain.