49

Wendy Kurant

Born in Africa (probably in Senegal or Gambia), Phillis Wheatley was enslaved at the age of seven or eight when she was bought by John Wheatley (1703–1778) of Boston to serve as his wife Susannah’s companion. Susannah fostered Wheatley’s intellectual avidity by having her daughter Mary oversee Wheatley’s education. Wheatley became well-read in the Bible; classical literature, including some of the classics in their original Latin; and English literature, responding especially to the works of Alexander Pope (1688–1744), master of the heroic couplet, and John Milton. She also converted to Christianity, becoming a member of the Old South Congregational Church.

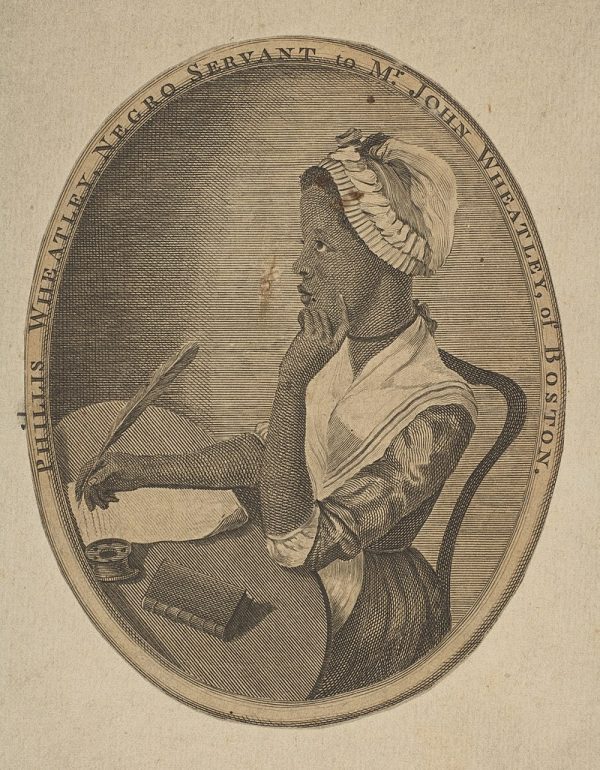

Figure 1. Phyllis Wheatley

Her first poem, “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin” (1767), was published in the Newport Mercury. What brought her attention as a writer—let alone an articulate black female slave—was her 1771 broadside elegy on George Whitefield (1714–1770), a famous evangelist minister. Touted thenceforth as a prodigy, Wheatley traveled to London for the publication of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). There she became a minor celebrity, meeting the lord mayor of London, Benjamin Franklin, and William Legge, the 2nd Earl of Dartmouth (1731–1801). To the latter, she appealed for justice for those “snatched” from Africa, taken from their “parent’s breast” and deprived of freedom.

The same year that her Poems were published, Wheatley was freed from slavery. She was with Susannah when she died a year later. Wheatley married John Peters, a free black man, in 1778, the same year John Wheatley died. Wheatley and her husband lived in poverty. In 1779, a proposal for a second volume of her poetry appeared, promising several letters and thirty-three poems, but the promise was never fulfilled. None of the projected poems have been discovered, either. Over the course of her marriage, Wheatley lost two children and died in 1784 soon after the birth of her third. She and her infant were buried together in an unmarked grave.

In the past, her poetry was deemed unoriginal, as giving little sense of Africa, her race, or her life as a slave. This reading attests to Wheatley’s strategic success in opposing prevalent views of women, blacks, and slaves during her era. Her poems are now recognized for their strong assertion of equality among all humankind and their strong-minded expression of self to contemporary readers who denied that selfhood.

Source:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Phyllis Wheatley,” Wikimedia, CC-0.