Icons, an introduction

What is an icon?

In our time, we often refer to celebrities as cultural icons, pop icons, and fashion icons. Rebels are sometimes labeled iconoclasts. Icons are also the little images that populate the screens of our computers, phones, and tablets, which we click to open files and apps.

The word “icon” comes from the Greek eikо̄n, so, “icon” simply means image. In the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and other lands that shared Byzantium’s Orthodox Christian faith, “holy icons” were images of sacred figures and events.

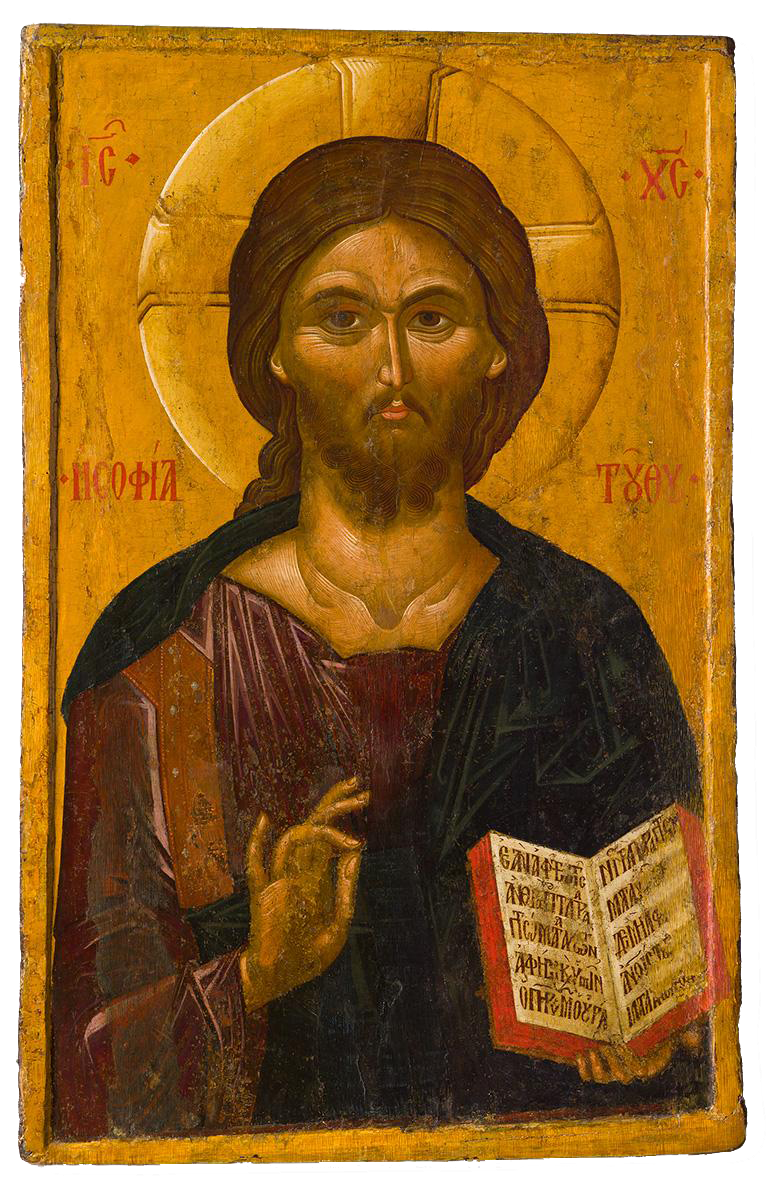

When art historians talk about icons today, they often mean portraits of holy figures painted on wood panels with encaustic or egg tempera, like this tempera icon of Christ from fourteenth-century Thessaloniki. But the Byzantines used the term icon more broadly, as this statement made by Church authorities in 787 C.E. shows:

Holy icons—made of colors, pebbles, or any other material that is fit—may be set in the holy churches of God, on holy utensils and vestments, on walls and boards, in houses and in streets. These may be icons of our Lord and God the Savior Jesus Christ, or of our pure Lady the holy Theotokos, or of honorable angels, or of any saint or holy man.

(Council of Nicaea II, 787 C.E.)

In Byzantium, icons were painted, but they were also carved in stone and ivory and fashioned from mosaics, metals, and enamels—virtually any medium available to artists.

Icons could be monumental or miniature. They were located in a variety of religious and non-religious settings, including as decoration on functional objects like this Eucharistic chalice.

And icons could depict a wide range of sacred subjects, such as Christ, the saints, and events from the Bible or the lives of saints.

Iconoclasm and the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”

Christians initially disagreed over whether religious images were good or bad. Texts from as early as the second and third century describe some Christians using religious images, which they illuminated and adorned with garlands, but these practices were not universal or standardized. Church authorities often criticized these practices, which reminded them of customs associated with pagan Greece and Rome, where images of gods and emperors were widely venerated.

By the eighth and ninth centuries, icons were increasingly popular, and arguments about religious images boiled over in what is called the “Iconoclastic Controversy.” The so-called “iconoclasts” (literally, “breakers of images”) opposed icons, arguing that God was transcendent and could not be depicted in art. The iconoclasts feared that Christians praying before icons were worshipping inanimate objects.

On the other hand, the “iconophiles” (literally “lovers of images”), also known as “iconodules” (literally “servants of images”), defended icons, arguing that since Jesus, the Son of God, was born with a visible human body, he could be depicted in images. The iconophiles maintained that rather than worshipping inanimate objects, they honored icons as a means of honoring the holy figures represented in icons.

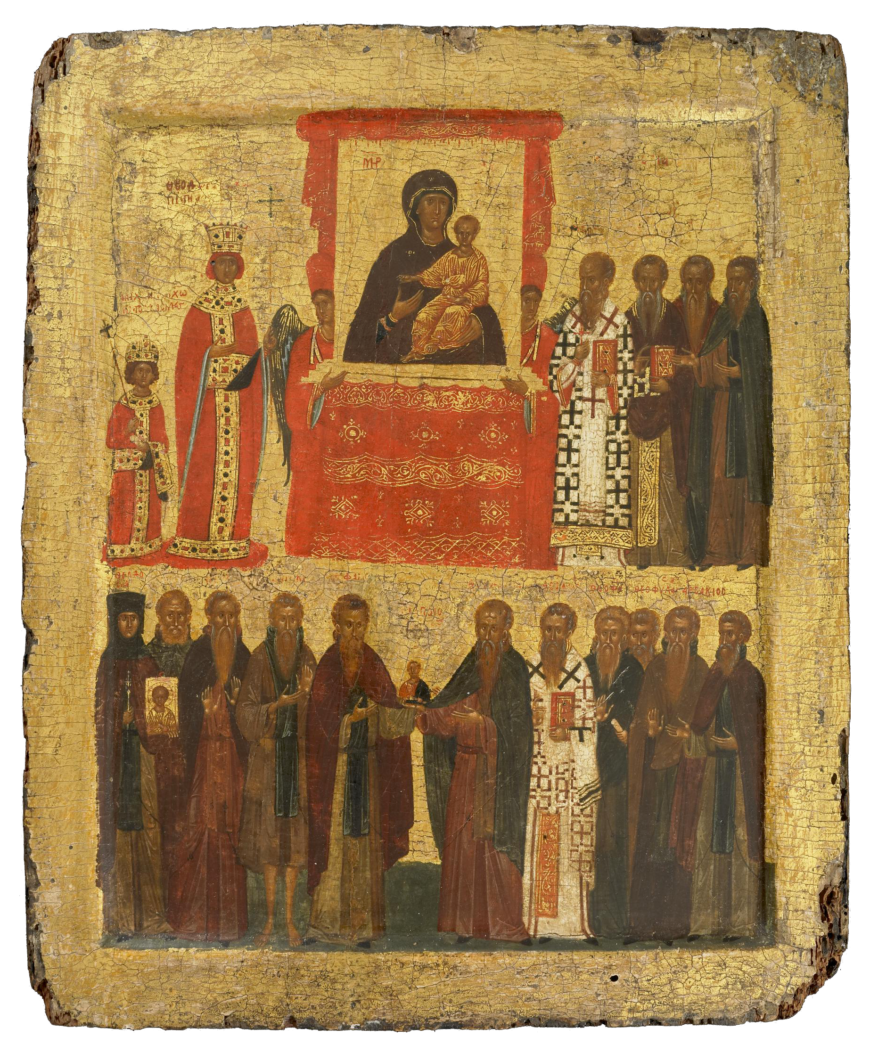

Imperial and Church authorities in favor of icons gathered at a council in the city of Nicaea in 787 to try to resolve the controversy, but it was not until 843 that the Church definitively affirmed the use of images, ending the Iconoclastic Controversy in what became known as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” To this day, icons continue to play important roles in the faith and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which is heir to the religious tradition of Byzantium.

In addition to affirming Christian images, the 787 Council of Nicaea II and subsequent 843 Triumph of Orthodoxy also enshrined devotional practices associated with icons. Christians should bow before and kiss icons, light candles and lamps, and burn incense before them. All of these acts of devotion directed at images were intended to pass to the holy figures represented. As a modern analogy, we might consider the ways many people frame and hang photos of loved ones in their homes, sometimes even embracing or kissing such images.

Ivory Panel with Archangel: A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is a transcript of a conversation held in the British Museum. The British Museum translates the text at the top of the panel as: “Receive the suppliant before you, despite his sinfulness.” To watch the video: https://youtu.be/f7J0WQsajX8.

Beth: We’re in the British Museum looking at a very large ivory panel. Usually ivories are very small.

Steven: This is huge and apparently it’s actually one half of a diptych. Now what’s interesting is even though it’s in the British Museum, it actually comes originally from Constantinople. This is a Byzantine object.

Beth: It looks like the other half of a diptych would have been on the left side. The angel who’s in this ivory—and let me just say, this ivory is probably about what, 18 inches?

Steven: Yes, I would say so. Probably by about five and a half or six.

Beth: Right. The other panel would have been on the left and the Arch Angel, who we see, seems to be looking in the direction of what would have been the other figure that would have been in the other panel.

Steven: You can further tell that the panel would have been on the left because you can see you can actually see three holes that would have been functioning as part of the hinge.

Beth: Right and a diptych of course means a work of art made out of two panels, as opposed to a triptych which is three panels.

Steven: We can assume that there would have been another saint on the other side; another angel perhaps.

Beth: Another angel or perhaps the angel giving this orb to a king or an emperor.

Steven: We see Greek text up at the top and below that we see this incredibly ornate arch with a cross above that and the cross is surmounting an orb. There seems to be almost a kind of sunburst behind it; very decorative, beautiful carving of a kind of ribbon or banner just below the wreath and then some broad open areas under some dentils. These are just architectural elements. We see Corinthian plasters framing the figure.

Beth: It actually reminded me of an apse in a church with an archway behind and those columns in maybe perhaps a kind of recessed space.

Steven: Even though this is carved, it’s such a shallow relief carving; it’s so flat. You do get a sense of real architectural space there and the figure himself is so interesting because it’s so classicizing in some ways. This is though very much a Byzantine rendering. Look at the size of the Archangel in relationship, for instance, to the staircase.

Beth: He is very large. Is that what you mean? He very much takes up that whole space as kind of a hierarchy of scale so that his size matches his divine nature.

Steven: This is very interesting because this is very classicizing. Look at the drapery…

Beth: Yes, that’s very classical.

Steven: …That he wears. Even up against the wings of; he’s an angel, he’s an Archangel.

Beth: He has his classical toga on.

Steven: Yes and it’s actually getting fairly late to see that kind of synthesis, right?

Beth: Even his hair, the curls in his hair look like a Roman sculpture, Roman portrait bust.

Steven: It’s true. If you stripped away the wings, if you stripped away the cross and the orb, you could be looking at a Roman portrait.

Beth: The detail here in the carving is remarkable. The lines that make up each of the feathers in the angel’s wings or the little circular swirling decorations in his cuff to the delicacy of his hand as he holds the staff, the other hand holding the orb with a cross on it, that symbol of power, but we know that we’re not in the classical world anymore the way that I know that is by not only his size in relationship to the architecture, but when I look down at his feet.

Steven: How so?

Beth: He doesn’t really stand on the ground. His feet sort of flatten out and hang over those stairs. He doesn’t really make contact with the ground in a meaningful way and that suggests to me a weightlessness, a kind of spirituality that reminds me of Byzantine and Medieval art.

Steven: The handling of the body—which by the way really is transparent behind the cloth—the body really does swell that cloth. It’s not that later Medieval rejection of the body below, but this is still coming out of the classical.

Beth: Look at his toes…. I mean this is such a strange combination of the spiritual and the human that is a very funny moment in early Christian and Byzantine art.

Steven: There is a kind of awkwardness with the synthesis; it hasn’t been worked out yet.

Beth: Right.

Steven: It really is clash of traditions.

Beth: Of Pagan and Christian.

Steven: Absolutely.

The Emperor Triumphant (Barberini Ivory): A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is a transcript of a conversation held at the Louvre Museum in Paris. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/9lVE3trJf1A.

Steven: We’re in the Musee du Louvre in Paris looking at a very large panel of ivory that is Byzantine and we date to the early 6th century.

Beth: These Byzantine ivories of this early date are very rare. There’s another one in the British Museum. This one shows an emperor on horseback in the central panel with four panels on the four sides, one of which is lost.

Steven: What’s remarkable to me is just how deeply carved and how energized the central panel is. There’s been tremendous care in representing not only fine details but also alternations between areas of deep carving and broad smooth areas, for instance of the horse’s body. This is so clearly an illustration of this moment of transition between the classical tradition and the Byzantine as we will come to know it. Should we start at the top?

Beth: Sure, we’ve got Christ in a medallion in the center with angels on either side. He makes a gesture of blessing and around him is a symbol of the sun, of the moon, and a star.

Steven: He holds a scepter with a cross and looks directly out at us. You can see that he’s been rendered not with the traditional long, thin face with a beard, but he’s young, he’s beardless and his hair is curly, which is very reminiscent of the classical tradition.

Beth: Those two angels are very reminiscent of Nike figures, of figures of victory that we would see in Ancient Roman carving.

Steven: Although the drapery has been simplified and is now rendered by cuts rather than fully formed folds. And below this dynamic image of the emperor riding in on a horse toward us, an emperor who is a Christian. We can see him holding the reigns as he turns the horse, planting his lance down on the ground. Look at the round forms of the horse’s breast, or the leg that comes out and the way that the reign pulls the horse’s head back in. There seems to be such a sensitivity to creating a sense of volume, to establishing space for this foreshortened horse to occupy.

Beth: Art historians believe that the fineness of this carving indicates that this was made in a workshop in Constantinople in the capital of what we think of as the Byzantine Empire, but really was then the Roman Empire.

Steven: Now we don’t know who this imperial figure is, in fact we’re really just guessing that it is an imperial figure. But we feel like we’re on fairly firm grounds because of the fineness of the carving.

Beth: All the iconography is imperial. We have a Nike figure, a figure of victory presenting the emperor with a palm branch, a symbol of victory.

Steven: We guess that in her right hand she would’ve originally been holding a crown to place on his head.

Beth: As in so many other images of Roman emperors, nearby is the figure of a vanquished foe.

Steven: Look how that smaller figure behind the horse is represented. He’s wearing a Phrygian cap which was a symbol of the other, it was a symbol of the barbarian. He’s wearing pants, he’s wearing closed shoes. All of these things were symbols of the barbarian.

Beth: Barbarian here means foreigner, someone outside of the Roman Empire.

Steven: Now under the horse we see a female figure. She’s quite classicizing in the way that her drape has fallen off one shoulder. She holds in the folds of her drapery, fruits. So she becomes a symbol of plenty. Art historians think she represents perhaps conquered lands or the bounty of the earth.

Beth: We could see her as a personification of the earth submitting to the emperor by holding the underside of his foot.

Steven: If you look closely at the central panel you’ll see that there are areas where there would have been small gems or pearls. We can see the gem for instance between the eyes of the horse. But you can also see that there would have been many others that would have decorated the horse’s body.

Beth: So that central panel is in such high relief. Look at the drapery flying back behind the emperor. There’s a real sense of energy here that’s contrasted with the figure of, we think, a general, or at least a very high level officer who’s presenting the emperor with a statue representing victory.

Steven: So that general is represented in much shallower relief and we can see that he’s in a truncated architectural space. resides on earth, under god in heaven.

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

A symbol of Byzantium

The great church of the Byzantine capital Constantinople (Istanbul) took its current structural form under the direction of the Emperor Justinian I. The church was dedicated in 537, amid great ceremony and the pride of the emperor (who was sometimes said to have seen the completed building in a dream). The daring engineering feats of the building are well known. Numerous medieval travelers praise the size and embellishment of the church. Tales abound of miracles associated with the church. Hagia Sophia is the symbol of Byzantium in the same way that the Parthenon embodies Classical Greece or the Eiffel Tower typifies Paris.

Each of those structures express values and beliefs: perfect proportion, industrial confidence, a unique spirituality. By overall impression and attention to detail, the builders of Hagia Sophia left the world a mystical building. The fabric of the building denies that it can stand by its construction alone. Hagia Sophia’s being seems to cry out for an other-worldly explanation of why it stands because much within the building seems dematerialized, an impression that must have been very real in the perception of the medieval faithful. The dematerialization can be seen in as small a detail as a column capital or in the building’s dominant feature, its dome.

Let us start with a look at a column capital

The capital is a derivative of the Classical Ionic order via the variations of the Roman composite capital and Byzantine invention. Shrunken volutes appear at the corners decorative detailing runs the circuit of lower regions of the capital. The column capital does important work, providing transition from what it supports to the round column beneath. What we see here is decoration that makes the capital appear light, even insubstantial. The whole appears more as filigree work than as robust stone capable of supporting enormous weight to the column.

Compare the Hagia Sophia capital with a Classical Greek Ionic capital, this one from the Greek Erechtheion on the Acropolis, Athens. The capital has abundant decoration but the treatment does not diminish the work performed by the capital. The lines between the two spirals dip, suggesting the weight carried while the spirals seem to show a pent-up energy that pushes the capital up to meet the entablature, the weight it holds. The capital is a working member and its design expresses the working in an elegant way.

The relationship between the two is similar to the evolution of the antique to the medieval seen in the mosaics of San Vitale. A capital fragment on the grounds of Hagia Sophia illustrates the carving technique. The stone is deeply drilled, creating shadows behind the vegetative decoration. The capital surface appears thin. The capital contradicts its task rather than expressing it.

This deep carving appears throughout Hagia Sophia’s capitals, spandrels, and entablatures. Everywhere we look stone visually denying its ability to do the work that it must do. The important point is that the decoration suggests that something other than sound building technique must be at work in holding up the building.

A golden dome suspended from heaven

We know that the faithful attributed the structural success of Hagia Sophia to divine intervention. Nothing is more illustrative of the attitude than descriptions of the dome of Hagia Sophia. Procopius, biographer of the Emperor Justinian and author of a book on the buildings of Justinian is the first to assert that the dome hovered over the building by divine intervention.

“…the huge spherical dome [makes] the structure exceptionally beautiful. Yet it seems not to rest upon solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from Heaven.” (from “The Buildings” by Procopius, Loeb Classical Library, 1940, online at the University of Chicago Penelope project)

The description became part of the lore of the great church and is repeated again and again over the centuries. A look at the base of the dome helps explain the descriptions.

The windows at the bottom of the dome are closely spaced, visually asserting that the base of the dome is insubstantial and hardly touching the building itself. The building planners did more than squeeze the windows together, they also lined the jambs or sides of the windows with gold mosaic. As light hits the gold it bounces around the openings and eats away at the structure and makes room for the imagination to see a floating dome.

It would be difficult not to accept the fabric as consciously constructed to present a building that is dematerialized by common constructional expectation. Perception outweighs clinical explanation. To the faithful of Constantinople and its visitors, the building used divine intervention to do what otherwise would appear to be impossible. Perception supplies its own explanation: the dome is suspended from heaven by an invisible chain.

Advice from an angel?

An old story about Hagia Sophia, a story that comes down in several versions, is a pointed explanation of the miracle of the church. So goes the story: A youngster was among the craftsmen doing the construction. Realizing a problem with continuing work, the crew left the church to seek help (some versions say they sought help from the Imperial Palace). The youngster was left to guard the tools while the workmen were away. A figure appeared inside the building and told the boy the solution to the problem and told the boy to go to the workmen with the solution. Reassuring the boy that he, the figure, would stay and guard the tools until the boy returned, the boy set off. The solution that the boy delivered was so ingenious that the assembled problem solvers realized that the mysterious figure was no ordinary man but a divine presence, likely an angel. The boy was sent away and was never allowed to return to the capital. Thus the divine presence had to remain inside the great church by virtue of his promise and presumably is still there. Any doubt about the steadfastness of Hagia Sophia could hardly stand in the face of the fact that a divine guardian watches over the church.[1]

Damage and repairs

Hagia Sophia sits astride an earthquake fault. The building was severely damaged by three quakes during its early history. Extensive repairs were required. Despite the repairs, one assumes that the city saw the survival of the church, amid city rubble, as yet another indication of divine guardianship of the church.

Extensive repair and restoration are ongoing in the modern period. We likely pride ourselves on the ability of modern engineering to compensate for daring 6th Century building technique. Both ages have their belief systems and we are understandably certain of the rightness of our modern approach to care of the great monument. But we must also know that we would be lesser if we did not contemplate with some admiration the structural belief system of the Byzantine Age.

Historical outline

Isidore and Anthemius replaced the original 4th-century church commissioned by Emperor Constantine and a 5th-century structure that was destroyed during the Nika revolt of 532. The present Hagia Sophia or the Church of Holy Wisdom became a mosque in 1453 following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans under Sultan Mehmed II. In 1934, Atatürk, founder of Modern Turkey, converted the mosque into a museum.

San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic

San Vitale is one of the most important surviving examples of Byzantine architecture and mosaic work. It was begun in 526 or 527 under Ostrogothic rule. It was consecrated in 547 and completed soon after.

One of the most famous images of political authority from the Middle Ages is the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and his court in the sanctuary of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. This image is an integral part of a much larger mosaic program in the chancel (the space around the altar).

A major theme of this mosaic program is the authority of the emperor in the Christian plan of history.

The mosaic program can also be seen to give visual testament to the two major ambitions of Justinian’s reign: as heir to the tradition of Roman Emperors, Justinian sought to restore the territorial boundaries of the Empire. As the Christian Emperor, he saw himself as the defender of the faith. As such it was his duty to establish religious uniformity or Orthodoxy throughout the Empire.

Who’s Who in the Mosaic and What They Carry

In the chancel mosaic Justinian is posed frontally in the center. He is haloed and wears a crown and a purple imperial robe. He is flanked by members of the clergy on his left with the most prominent figure the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna being labelled with an inscription. To Justinian’s right appear members of the imperial administration identified by the purple stripe, and at the very far left side of the mosaic appears a group of soldiers.

This mosaic thus establishes the central position of the Emperor between the power of the church and the power of the imperial administration and military. Like the Roman Emperors of the past, Justinian has religious, administrative, and military authority.

The clergy and Justinian carry in sequence from right to left a censer, the gospel book, the cross, and the bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. This identifies the mosaic as the so-called Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist.

Justinian’s gesture of carrying the bowl with the bread of the Eucharist can be seen as an act of homage to the True King who appears in the adjacent apse mosaic (image left).

Christ, dressed in imperial purple and seated on an orb signifying universal dominion, offers the crown of martyrdom to St. Vitale, but the same gesture can be seen as offering the crown to Justinian in the mosaic below. Justinian is thus Christ’s vice-regent on earth, and his army is actually the army of Christ as signified by the Chi-Rho on the shield.

Who’s in Front?

Closer examination of the Justinian mosaic reveals an ambiguity in the positioning of the figures of Justinian and the Bishop Maximianus. Overlapping suggests that Justinian is the closest figure to the viewer, but when the positioning of the figures on the picture plane is considered, it is evident that Maximianus’s feet are lower on the picture plane which suggests that he is closer to the viewer. This can perhaps be seen as an indication of the tension between the authority of the Emperor and the church.

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

At Mount Sinai Monastery

One of thousands of important Byzantine images, books, and documents preserved at St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai (Egypt) is the remarkable encaustic icon painting of the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (“Icon” is Greek for “image” or “painting” and encaustic is a painting technique that uses wax as a medium to carry the color).

The icon shows the Virgin and Child flanked by two soldier saints, St. Theodore to the left and St. George at the right. Above these are two angels who gaze upward to the hand of God, from which light emanates, falling on the Virgin.

Selectively classicizing

The painter selectively used the classicizing style inherited from Rome. The faces are modeled; we see the same convincing modeling in the heads of the angels (note the muscles of the necks) and the ease with which the heads turn almost three-quarters.

The space appears compressed, almost flat, at our first encounter. Yet we find spatial recession, first in the throne of the Virgin where we glimpse part of the right side and a shadow cast by the throne; we also see a receding armrest as well as a projecting footrest. The Virgin, with a slight twist of her body, sits comfortably on the throne, leaning her body left toward the edge of the throne. The child sits on her ample lap as the mother supports him with both hands. We see the left knee of the Virgin beneath convincing drapery whose folds fall between her legs.

At the top of the painting an architectural member turns and recedes at the heads of the angels. The architecture helps to create and close off the space around the holy scene.

The composition displays a spatial ambiguity that places the scene in a world that operates differently from our world, reminiscent of the spatial ambiguity of the earlier Ivory panel with Archangel. The ambiguity allows the scene to partake of the viewer’s world but also separates the scene from the normal world.

New in our icon is what we might call a “hierarchy of bodies.” Theodore and George stand erect, feet on the ground, and gaze directly at the viewer with large, passive eyes. While looking at us they show no recognition of the viewer and appear ready to receive something from us. The saints are slightly animated by the lifting of a heel by each as though they slowly step toward us.

The Virgin averts her gaze and does not make eye contact with the viewer. The ethereal angels concentrate on the hand above. The light tones of the angels and especially the slightly transparent rendering of their halos give the two an otherworldly appearance.

Visual movement upward, toward the hand of God

This supremely composed picture gives us an unmistakable sense of visual movement inward and upward, from the saints to the Virgin and from the Virgin upward past the angels to the hand of God.

The passive saints seem to stand ready to receive the veneration of the viewer and pass it inward and upward until it reaches the most sacred realm depicted in the picture.

We can describe the differing appearances as saints who seem to inhabit a world close to our own (they alone have a ground line), the Virgin and Child who are elevated and look beyond us, and the angels who reside near the hand of God transcend our space. As the eye moves upward we pass through zones: the saints, standing on ground and therefore closest to us, and then upward and more ethereal until we reach the holiest zone, that of the hand of God. These zones of holiness suggest a cosmos of the world, earth and real people, through the Virgin, heavenly angels, and finally the hand of God. The viewer who stands before the scene make this cosmos complete, from “our earth” to heaven.

The Chora Church

The Chora Church’s full name is the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora. The church was first built in Constantinople during the early fifth century. Its name references its location outside the city’s fourth-century walls. Even when the walls were expanded in the early fifth century by Theodosius II, the church maintained its name.

Inside the church is a set of frescoes and mosaics that survived the church’s conversion into a mosque in the sixteenth century when its Christian imagery was plastered over. In 1948 the church became a museum after undergoing extensive restoration to uncover and restore its fourteenth-century decoration. It is now known as the Kariye Museum or Kariye Camii.

Architecture

The Chora Church that stands today is the result of its third stage of construction. This building and the interior decoration were completed between 1315 and 1321 under the Byzantine statesman Theodore Metochites. Metochites’ additions and reconstruction in the fourteenth century enlarged the ground plan from the original small, symmetrical church into a large, asymmetrical square that consists of three main areas:

- An inner and outer narthex or entrance hall.

- The naos or main chapel.

- The side chapel, known as the parecclesion. The parecclesion serves as a mortuary chapel and held eight tombs that were added after the area was initially decorated.

There are six domes in the church, three over the naos (one over the main space and two over smaller chapels), two in the inner narthex, and one in the side chapel. The domes are pumpkin-shaped, with concave bands radiating from their centers, and richly decorated with frescoes and mosaics that depict images of Christ and the Virgin at the center, with angels or ancestors surrounding them in the bands.

Mosaics

Mosaics extensively decorate the narthices of the Chora Church. The artists first decorated the church in the naos and then completed the work in the inner and outer narthices, which results in differences in the mosaics’ execution as the style progressed to show more liveliness and subtlety.

The surviving mosaics in the naos depict the Virgin and Child and the Dormition of the Virgin, a koimesis scene depicting the Virgin after death before she ascends to Heaven. This scene, located above the west door, depicts the Virgin in blue lying on a sarcophagus draped in purple and gold. Christ, in gold, stands behind the Virgin surrounded by a mandorla and holds an infant, representing the Virgin’s soul. The figures in the scene all have a certain weightiness that helps to ground them, adding an element of naturalism.

The mosaics found in the narthices of the Chora Church also depict scenes of the lives of the Virgin and Christ, while other scenes depict Old Testament stories that prefigure the Salvation. In the outer narthex, above the doorway to the inner narthex is a mosaic depicting Christ as the Pantocrator, the ruler or judge of all, in the center of a dome. The mosaic depicts a stern-faced Christ against a gold backdrop holding the gospels in one hand while gesturing with the other. An inscription in the mosaic reads, “Jesus Christ, Land of the Living.”

In another important scene above the entrance to the naos, Christ Enthroned is depicted receiving the donor of the church. The scene follows the Byzantine convention of depicting an architectural donation with an image of Christ in the center and the donor kneeling beside him, holding a model of his donation.

Here, Christ sits on a throne in a position similar to the Pantocrater, holding a book of gospels while his other hand gestures. The donor Theodore Metochites, wearing the clothing of his office, kneels on Christ’s right. He offers Christ a representation of the Chora Church in his hands. An inscription gives his titles.

Frescoes

The walls and ceilings of the parecclesion are decorated with scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin, and themes of salvation befitting for a mortuary chapel. Like the mosaics, the scenes are painted in the upper levels of the building. The lower levels are reserved for painted images of saints and prophets and a decorative dado that mimics marble revetment.

The entirety of the parecclesion is covered in fresco scenes and painted images, creating an overwhelming sense of splendor and glory that ultimately brings the viewer to the final scenes of salvation and judgment.

Anastasis

The most important of these frescoes is the Anastasis, a representation of the Last Judgment, in the apse of the eastern bay. This image depicts Christ in Hell, saving the souls of the Old Testament. Christ stands in the center grasping the wrists of Adam and Eve, whom he raises from their sarcophagi. Saints, prophets, martyrs and other righteous souls, including John the Baptist, King David, and King Solomon, from the Old Testament stand on either side of Christ. Christ, standing over a bound Satan, wears a white robe and is framed by a white and light blue mandorla.

The image is the culmination of the parecclesion’s fresco cycle and one of the most impressive Late Byzantine paintings. Christ stands in an active, chiastic position. His arms reach out to Adam and Eve and his feet are positioned on uneven ground, providing the sensation of imbalance as he retrieves righteous souls.

The figures themselves are rendered in a softer, subtler mode. The harsh, jagged drapery has softened slightly with fluid and delineated folds. The expression of Christ and the others are dignified and stern. The Old Testament figures on either side gesture towards the scene, signaling the future of the faithful, as they wait for Christ to bring them into Heaven.

Changing Representations of Christ

The depictions of Christ in the Chora Church differ greatly from those of the third and fourth centuries. Recalling Early Christian art, Christ often appears clean shaven and youthful, sometimes cast as the Good Shepherd who tends and rescues his flock from danger. At a time when Christianity was illegal, Christians would have found such imagery of a protector reassuring.

By the fourteenth century, when Theodore Metochites funded the interior decoration, Christianity was no longer a fledgling faith; it was a state religion in which even the emperor recognized Christ as the ultimate authority. The images of Christ in the frescoes and mosaics of the Chora Church depict an authoritative, bearded man who occupies the role of both savior and judge. As an archetypal symbol of authority and wisdom through the ages, the beard would have been a logical choice for the face of the most supreme leader.