20 18. The Three Little Eggs: A Swazi Tale

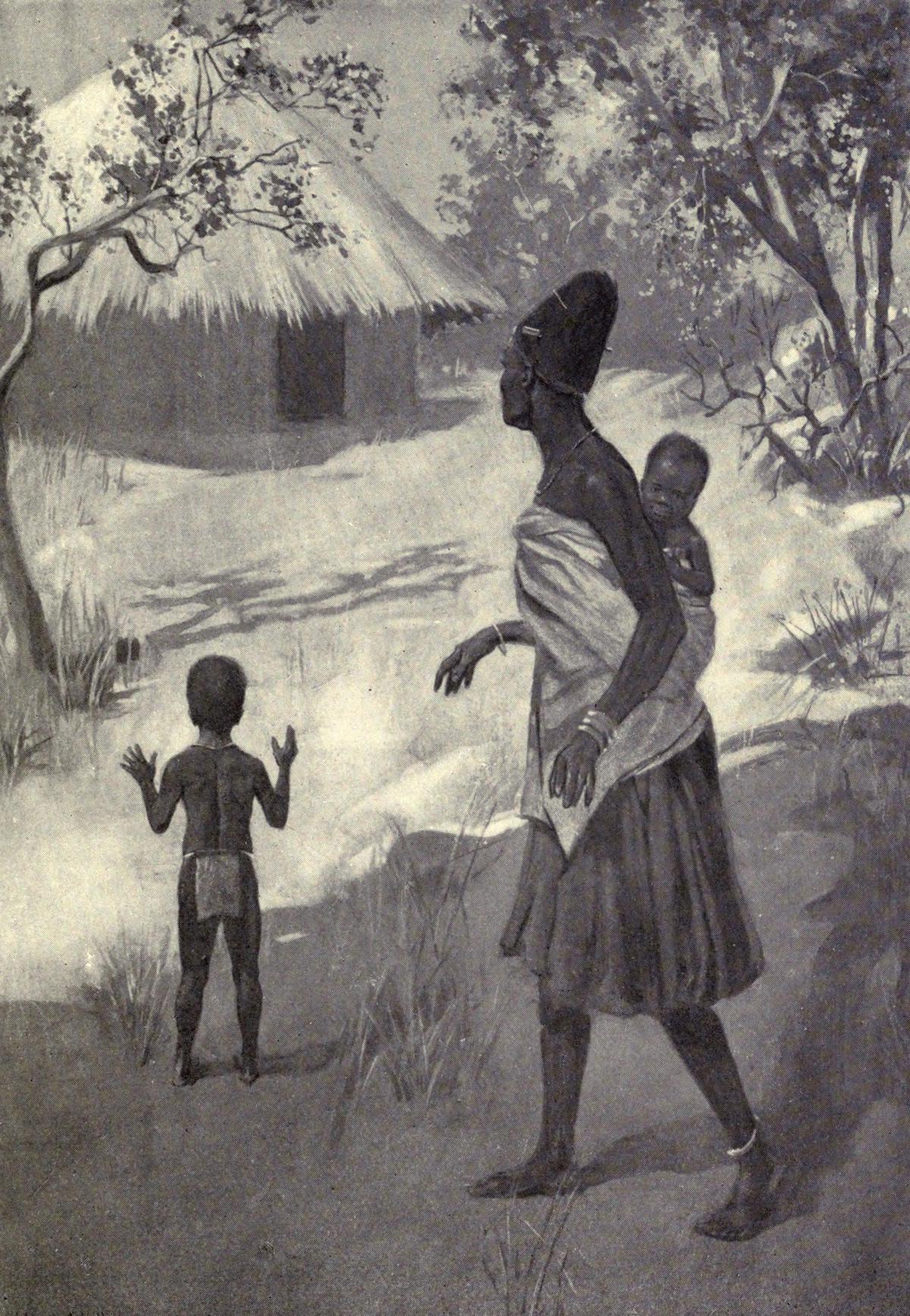

[From Fairy Tales from South Africa by Mrs. E. J. Bourhill and Mrs. J. B. Drake, 1908. See item #36 in the Bibliography. The illustration is by W. Herbert Holloway.]

It was very early morning in mid-winter. The sun was just rising over the great plains in a silver haze which melted into pale gold as the wide stretches of veld came into view, burnt dry with the summer heat. The rains had long ago been over. The sun shone every day and all day, with a pleasant temperate heat in a clear heaven. The whole country appeared golden, save where the watercourses ran, and a few great evergreen trees stood up in vivid contrast to the bleached summer grasses.

By the side of a great fig-tree there was one poor little hut surrounded by a plaited fence. Close to it was a little patch of cultivated ground where a few dried mealie-stalks were still standing. The air was very cold and raw so that it chilled you through and through, but the sun had barely touched the top of the great tree when a woman came out hurriedly from the hut and passed through the kraal gate. You could see she was a married woman by her full kilt of black ox-skins and her peaked headdress. Besides, she carried on her back the dearest little baby girl, wrapped in a goat-skin and half asleep, and by her side ran a merry little boy. The mother herself was still young and pretty, but her face was worn and thin, and if you had looked close, you would have seen that her arms were covered with scars and burns, as if she had been badly used.

She stood for a few minutes and looked first towards the wide plains. Then she turned to the other side where great hills rose up, ruddy and golden in the early sun. She seemed to hesitate; then she turned to the mountains and was soon on a tiny pathway which led by many windings to a wooded gorge hundreds of feet above the plains. She did not sing as she went, and often cast frightened looks behind her. But no one followed and, after a time, as the hut disappeared from view and the sun made all things warm and pleasant, she grew less anxious and went on her way more quietly.

For she was running away from her husband. She had been married now four years, and every year he had been more unkind. He not only worked her very hard and gave her scarcely anything to eat, but he also often beat her and had even branded her with hot irons till she screamed with pain. She was good and obedient and tried hard to please him, but he only became more and more cruel to her and her children. Two days before he had gone off to a big dance in a far-away kraal. The poor woman so dreaded his return that she decided to run away and beg her living as best she could. She knew there were great chiefs on the other side of the mountains, and big cities; she was a good worker, and doubtless they would give her food.

She walked on and on, and the baby girl woke up and began to laugh and play. They were now following the course of a stream, but only a tiny trickle of water remained, and the ferns were withered, and the thick bushes dry and leafless. All at once the mother saw a fluffy white nest hanging on a long bough.

“How pretty!” said she. “That will be the very thing to amuse my baby.”

She went to the bough and detached the soft white nest while her little son looked on with much interest. To her great surprise, for it was yet many months to spring-time, she found it contained three little eggs.

“Hold it fast,” said she to her little baby, “and do not smash the little eggs on any account.”

Then she journeyed on once more. The sun was sinking fast, and the air grew colder and colder, for on the hill-tops there is sharp frost every night. No hut was in sight, though they were now on more level ground, and the poor mother had no covering but her one goat-skin, and no food. “Where shall I rest tonight?” said she to herself. “There is nothing to be seen but the open country.”

Then she heard a tiny voice at her ear, “Take the road to the right; it will lead you to a safe place.”

She turned and looked, and found it was one of the little eggs in the fluffy white nest! In very truth she saw there was a tiny pathway to the right which she had not noticed before. She took it at once, and just as the sun disappeared and the white frost began to show, she found a beautiful hut under the side of a great rock. No one seemed to live there, but it was warm and cosy, and all ready for her use. Beautiful karosses of ox-skin and goat-skin hung on the walls; food was already prepared in little red pots — crushed mealies and peanuts, and in the calabashes was an abundance of delicious thick amasi. The little boy and baby girl cried with delight, and you can imagine how pleased the poor mother was. The little nest was first carefully laid aside. Then both mother and children ate a good meal, for they were very hungry.

The little boy fell asleep at once, covered with the warm skins, but his sister cried and would not lie down quietly. So her mother tied her on her back once more and sang a cradle-song, which is as pretty a thing as you will hear. She swung gently to and fro, moving her arms as well in time to the low chant:

Tula, mtwana;

Binda, mtwana;

U nina u fulela;

U nina u fulela;

Tula, mtwana.

Be quiet, my baby;

Be still, my child.

Your mother has gone to get green mealies;

Your sisters are all gone gathering wood;

So be quiet, baby, be still.

Your father has gone a-walking;

He has gone to drink good beer.

Your mother is working with a will;

So be quiet, baby, be still.

Soon the tiny head leaned forward, the little round arms relaxed, and the baby girl was fast asleep. The tired mother laid her down, and in a few moments was dreaming by her children’s side.

The next morning they set forth again, much refreshed; they continued on the same path, and the baby girl carried the little eggs as before. Towards mid-day they came to a place where two ways met. The mother stood looking at the two paths for a long while, uncertain which to take. Then a tiny voice spoke in her ear. It was the second little egg this time. “Take the road to the left,” said he.

So she turned and followed the left-hand path till she came in sight of an enormous hut, three times as big as any she had ever seen before. She went straight up to it and looked in at the door, full of curiosity. It was like no hut she had ever seen. The calabashes and pots were all blood-red in colour, and very thin; as the breeze came in at the door, they swayed like bubbles and nearly fell for they were as light as air. One big pot was blown right across the room, and as the poor mother’s eyes followed it, she all but screamed aloud for, on the other side, lay a huge monster, fast asleep. He was immensely tall and very stout, his body was covered with tufts of brick-red hair, on his head were two horns, and his long tail lay curled across his knees. He was an Inzimu, without any doubt, and if he awoke he would kill the mother and both her babies and eat them up.

“”Whatever shall I do?” cried the mother as she ran from the door. “My little ones will both be killed.”

Then the third little egg spoke up. “Do you see that big stone? Carry it with you and climb on top of the hut.”

The mother looked around, for many rocks were near. She soon saw a round white stone, just of a size to drop through the thatched roof of the hut and kill anyone it fell on. But it was far beyond her power to lift it.

“However can I pick it up?” said the poor woman. “It is so heavy.”

“Do as I bid you,” said the egg.

So she stooped down and tried to lift the stone. To her great surprise, she found it quite light, and she took it to the back of the hut. Then she lifted her babies onto the roof and climbed up herself afterwards with the stone in her hand.

“Now let the stone drop on top of the monster,” said the egg.

The mother was just peering through the thatch to find the exact spot under which the monster lay when the door opened and in came a second ogre, dragging after him several dead bodies.

“Now we shall certainly be seen,” said the mother. “All is over.” But she kept quiet and did not move. The second Inzimu began to chop up one of his victims for the evening meal. Once he stopped, sniffed the air, and said, “There is something good hidden in this hut, but I can’t make out where it is.”

He looked all round carefully but never thought of the roof, and presently he put his supper on to boil and sat down to watch it. Soon both Inzimus were fast asleep. The mother then looked at her stone and said, “Here are two Inzimus; I cannot kill both. What am I to do next?”

“Come down as quietly as you can,” said all the little eggs at once, “and run with the babies as fast as possible.”

She slipped quietly down, and the little boy helped her with the baby. In a few minutes they were away, trembling in every limb, but the Inzimus did not wake up, and soon the big hut was out of sight.

The poor mother breathed again and hoped that now at last she would find a kraal and human beings to talk to. The path wound in and out among bushes. They grew ever thicker and more thorny, great trees began to appear, and it was soon impossible to walk save in the one direction. The path gave a sudden turn, and there, under a huge evergreen tree, was a horrible ogress. She lay right across the path, fast asleep, for the afternoon sun was warm. No doubt she was on her way home to the big hut. She was even uglier than the Inzimus, for she had a hideous snout like a wolf’s and one little horn just between her eyes. She snored most terribly, so that the branches of the tree shook.

Then the mother thought her last hour had really come, for she could not return and the bush was too thick on either side for her to escape.

But the little eggs did not desert her; two little voices sounded together. “Look on your right: there lies a big axe.”

She looked and, sure enough, a great axe lay winking in the sun. It was so large that it must have belonged to the ogress, but the mother seized it quickly.

“Now,” said the little eggs again, “take that in your hand, go softly to the tree, and lift your babies into the low branches. When they are safe, climb up yourself and creep along the great arm which is over the monster’s head.”

The mother crept softly to the tree and lifted her little son up into the branches. The trunk was smooth and round, and the branches were many and not far from the ground, so the little boy was able to hold his baby sister when they were safe among the leaves; the mother mounted herself and crept forward right over the monster’s head, the axe in her hand. She nearly fell off with fright, but the little eggs spoke again.

“Aim the axe at the monster’s head.”

She threw it with all her force and hit the ogress just above her horn, but the ogress was only stunned, not killed.

“Slip down from the tree,” said the third little egg, “and chop off the monster’s head quickly before she revives.”

The mother was down in a moment, ran forward with desperate courage, and in a few minutes she had severed the monster’s head from its body.

When it was done, she stood back to recover herself, but could scarcely believe her eyes as she looked. For out of the monster came men, women, and children, cattle and goats, one after another, till they filled the path and had to pass along to open ground. Many hundreds appeared, for the ogress had eaten every kind of animal and whole families of men in her wicked life. When all had come, there were enough to people a great kraal. Each one on his arrival turned to thank the poor mother and her children, and, when all were there, the leaders came forward to ask her to be their Queen.

“But I should never have done it without the three little eggs,” said she, and turned to show them the little white nest. She barely touched it with her hands when it vanished away, and instead appeared three handsome Princes. The eldest took her hand and said, “You have freed us from a wicked enchantress by your courage. Your cruel husband is dead; he was killed in a quarrel the day you fled from home. Be my wife, and we will rule over these people forever.”

So the poor mother and her children found a happy home and much honour. And all the people shouted for joy because they had now both a King and a Queen.