3 Theatre Structures

Theatre Structures in Canada – Power Structures and The Board

Activity: Write out a list of all the people you believe work on a theatre production. Then look in the program for any large theatre company’s show. How many did you miss?

The list of people who work on any production is long! Once you also take into account the administrative or office staff, it can be a huge team. There are so many people involved in keeping a company running and getting each show on the stage.

Why do you need to know all of this?

I think it’s really counter-productive if people coming out of a theatre training program on the production side or on the marketing side don’t understand what the other does because that can lead to a lot of misunderstandings and potentially resentments. And we need to be a team. – Haanita Seval, Director of Marketing, PTE, Winnipeg, MB

It’s important to have a basic knowledge about the roles in theatre that you will interact with. How can you know who to talk to if you don’t understand what everyone does? Here’s a great example from a playwright’s perspective: Don’t Send Your New Play to the Director of Development — The Playwrights Realm

Currently and historically, the main model in Canada for theatre companies is that of a non-profit. There are a few commercial producers as well but they are rare. Non-profits are legally incorporated (meaning they register with the government) and have to follow a prescribed legal structure. Despite the artistic nature of theatre, a standard business style operating model has been in place since the time when many companies were formed in the 1960s and 70s. Some argue this system doesn’t serve the art and that innovation is needed to find a model that will allow for a non-hierarchical approach while acknowledging the reality of how unstable the industry can be. As the discussion of new models continues, this chapter provides an understanding of what the dominant model is or has been. This is an inherited reality but does not mean it is something that shouldn’t be critically examined and questioned. A great article on this topic is ‘Governance structures for theatres, by theatres’ by Yvette Nolan (Mass Culture • Mobilisation culturelle) and there is also the collection Governance Reimaginings (Generator).

“As arts organizations, our core reason to exist is to provide meaning for ourselves and the world in which we operate. It is not to create jobs. It is not to build beautiful buildings that revitalize downtowns. It is not to provide social status, generate profits, build endowments or have a string of deficit free fiscal years. It is not to organize or proselytize for a political agenda. And it is surely not to create art for art’s sake, however one interprets that phrase. These might be laudable byproducts of the work we do. But it is not why the arts exist. Art exists to create meaning for individuals, communities and societies. Arts organizations exist to make sure that this happens.”

– Arts Leadership: Creating Sustainable Arts Organizations by Kenneth Foster (p. xiv)

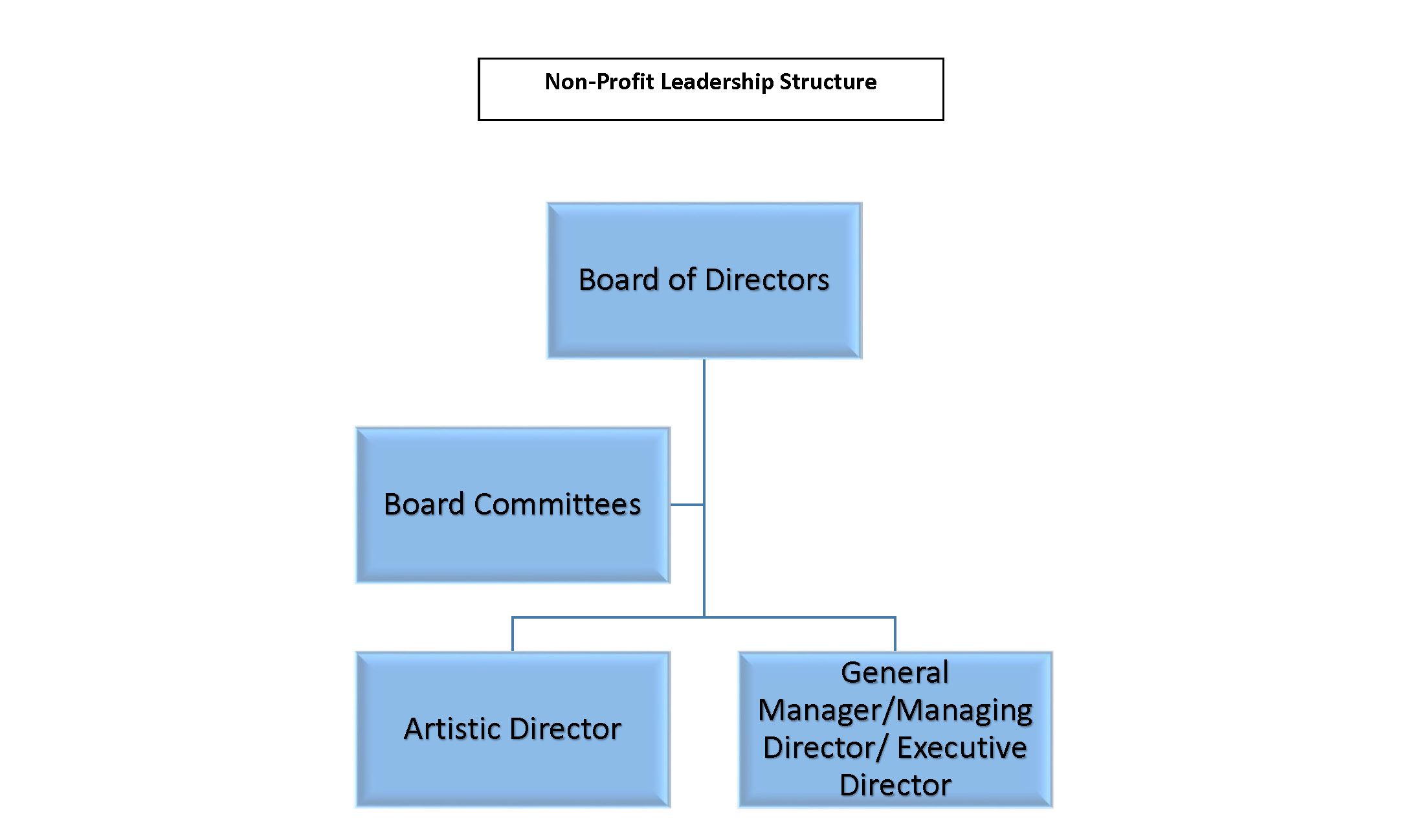

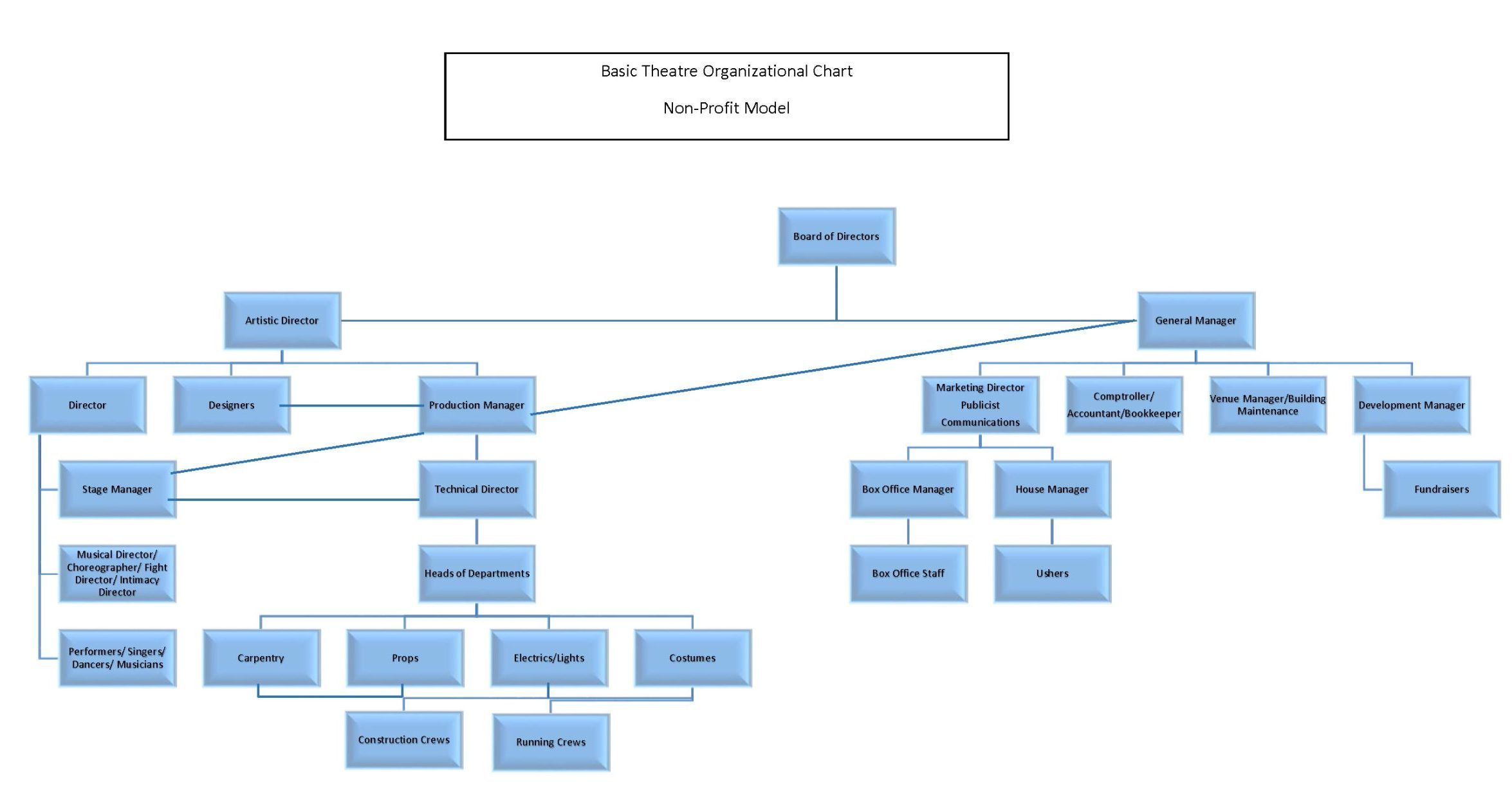

The non-profit reality is that most theatre companies are established with the legal obligation to serve and provide a benefit to community members. Each company is created to achieve specific goals, as per the information provided previously on mandate and mission. They can earn revenue to invest back into the cause (aka mandate), but they are specifically not set-up for anyone to profit. As a legally registered non-profit, a Board of Directors is required to oversee the governance. See the charts in this chapter for an overview of the basic structure and roles. The size of the company will greatly influence the structure and number of folks involved, whether they are paid staff or volunteers, and the level of administrative infrastructure. Smaller, independent companies may aim for a more collaborative or collective structure with members or advisors, but legally are still required to have a Board if they are registered non-profits.

For somebody, maybe, you’ve not always been interested in what’s going to happen to you when you get a certain age. But if you are, let’s start thinking about how in nonprofits, we don’t always do this, think about the health benefits and think about the pensions… so let’s make all of those a part of the discussion early on and also make sure that boards understand what all that is and what it means. I think working in the nonprofit sector is challenging anyway, right? It’s very challenging… because everybody has a lot of expectation of the nonprofit sector, because they always think you’re getting a lot of money from the government, I think. But, you know, it’s very, very, very challenging. – Donna Butt, Artistic Director, Rising Tide Theatre, Trinity, NL

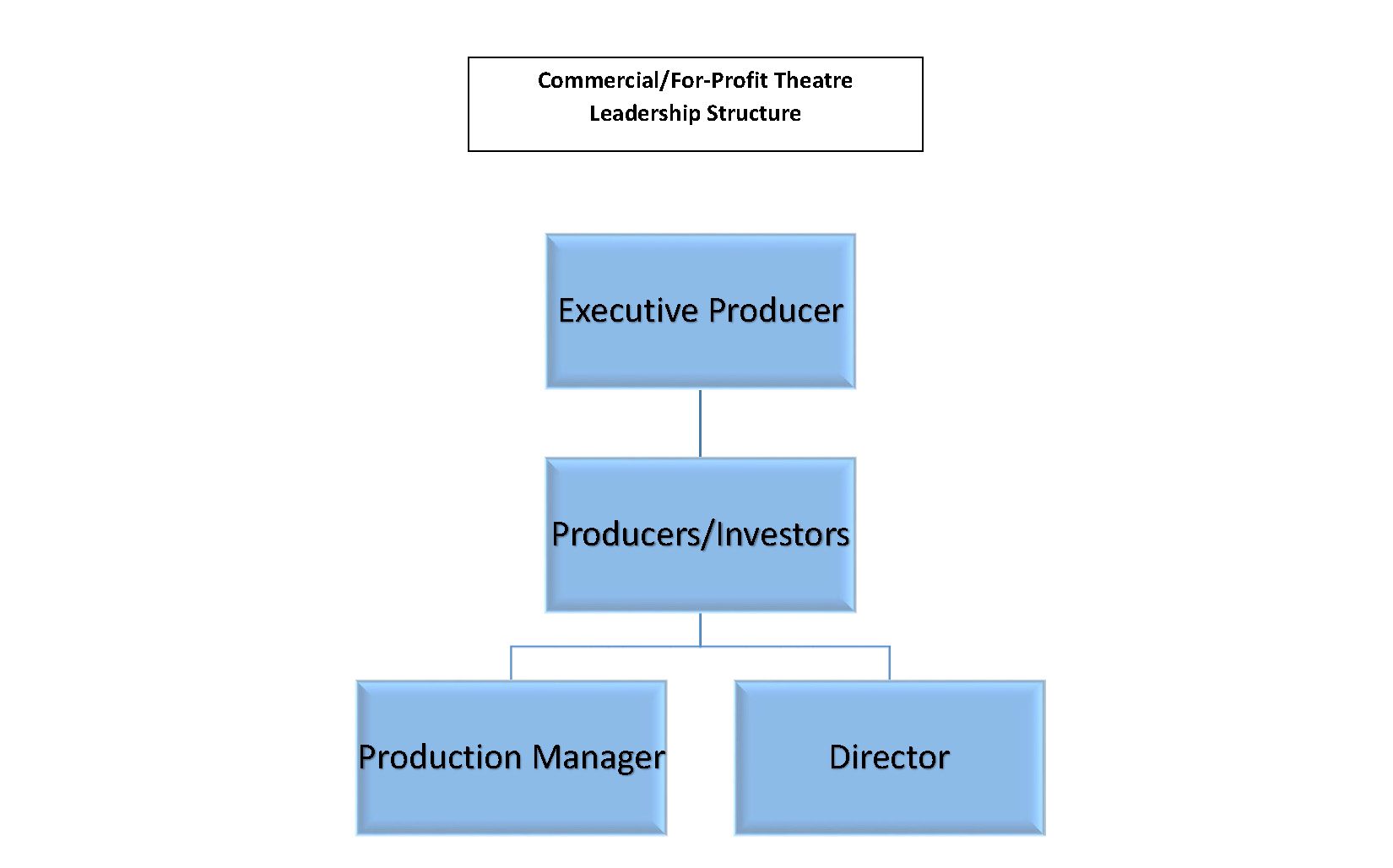

The few commercial theatres in Canada, are established to make a profit and therefore will have investors/producers rather than a volunteer Board. If it helps to give context, Broadway in New York is commercial with investors funding the shows hoping for a hit and a profit. If the show bombs and they lose their investment, they can at least write-it off as a loss on their taxes.

Activity: Think about why there are so few commercial theatres in Canada.

Why do theatres incorporate? Basically being a legally recognized non-profit means they can apply for public grants, do not have to pay taxes in the same way, and are eligible to become a registered charity. The general model is to incorporate provincially as a non-profit through a province’s company office. This requires doing a name search to make sure no other entity has the name that they want to use; developing a mission, constitution, by-laws for operation; and having a list of directors who have volunteered to play a role in governance. Once they have non-profit status, an organization can then apply federally for charitable status. Attaining charitable status means they can provide charitable tax receipts as an incentive for private donors and are also eligible to receive funds from charitable foundations. To be approved as a charity one needs to demonstrate that they meet the current criteria of providing a public benefit and have a Board of Directors in place. All of this comes with legal requirements, reporting, restrictions, and obligations.

If you are ever interested in digging in more intimately to how a theatre is governed, looking at bylaws for a theatre company can be really interesting. Generally, this legal document outlines the company’s objective, what positions make up their Board (officer positions and executive positions), how Board members are elected, any committees, what process is used for meetings and decision-making (Roberts Rules of Order being the most common), and how the by-laws can be changed.

Again, this very corporate structure is currently being challenged and even arts councils are now opening up to allow ad-hoc groups with different governance models to apply. The next update of this book may include a whole list of alternative theatre structures that are being put into practice!

I think that those are structures that can be very helpful and they’re all structures that can be very negative. And it really depends on the team of people that are working together. And I think the thing is… people assume a way of working in a structure, of working the way that those teams that you mentioned, staff, board, management, they assume relationships and ways of working that aren’t always the truth. And like anything, if you are an artist, you think, well, these are characters in this play – staff, board, management. What is their relationship? What could their relationship be? How do they work together? What is the story they’re trying to tell that brings them together? And how do we think creatively about these relationships? We can do anything we want. There are, of course, there are legitimate legal rules we need to follow, but we can be very creative about how we achieve those goals. And I think that the mistake a lot of people make is they take the structure that the big institution has and they apply it to the small and they are not the same. They don’t need to be the same and they shouldn’t be the same. And you’re limiting yourself. At the speed of which an institution can move and the rules that they have. Because, yeah, they’re tracking a ton of money, like they have a lot of things that they need to do. But the small, you know, doesn’t need that. It can be much freer and more creative and I think that’s an important thing to understand. And then I think, also don’t make companies all the time. Don’t make a company until you’re sure you need to be a company. – Ravi Jain, Artistic Director, Why Not Theatre, Toronto, ON

Coming back to the non-profit structure, as per the chart outlining the standard hierarchy of roles, you will have:

The Board – They are intended to make sure the organization is fulfilling its mandate, are following all legal obligations, and are fiscally responsible. Since they play a governance role, they set policies and make sure those policies are put into practice. (Boards have been a huge part of the theatre machine for decades. See the Board subset of this chapter for a deeper dive.)

Leadership – In a theatre context, leadership has historically been an Artistic Director who takes on the artistic leadership paired with a General Manager (or Managing Director) who handles the administrative side of running the company. Ideally it is a perfect team that works closely together, supports each other, and balances the art with the business. It is up to them to oversee the day to day and realize the company mission as well as any strategic plans. They manage resources, staffing, operations as well as make sure the season of shows can successfully take place. They report to the Board on finances, on how the company is meeting its mission, and on successes/challenges in meeting outlined goals. Some theatre companies have moved towards having an Executive Director or Chief Executive Officer rather than General Manager, this implies a position that focuses more on the strategic priorities rather than simply overseeing the daily operations. Large institutions such as Canadian Stage, Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, and Stratford Festival have an Executive Director. Some companies will also have a Producer, Producers, or Associate Producers as part of the management team. A few have tried creating one leadership role at the top with a sole CEO who is essentially both the Artistic Director and the General Manager. I won’t get into the pros and cons, but will say there has often been pushback and general concern about tipping more toward the business end of running a theatre company as opposed to the artistic focus. On the other end of the spectrum a trend toward more collaborative leadership is brewing with shared leadership among a group of team members.

Artistic Director (AD) – They are the visionary. Generally, they are also the face of the company. Within the parameters of the mission and resources, they will select the season of shows. Often in a season the Artistic Director will direct a number of productions. They make the programming decisions. For actors, playwrights, designers, and other creative roles this is the person who either will do the hiring or at least recommend potential artistic team members.

General Manager (GM) – As noted they manage the business end, working alongside the AD to oversee the annual budget. They will hire administrative team members and oversee these staff. Smaller independent companies often do not have a GM and the AD ends up doing it all with support of the Board. However, it is hard for a company to grow and sustain without administrative support and leadership.

Staff – Again the number of staff will depend on the size of the company. They are there to take on specific tasks to realize the company’s goals, keep the office running, make the shows happen, and manage audience interaction. In general, there is usually a division between operational staff that work in the office year-round (Marketing Manager, Production Manager, and so on) and those hired to support productions often on a contract basis (Carpenters, Box Office staff, and Buyers for example). Smaller companies may not have any operational staff but work project to project, hiring a production coordinator for a project or someone to manage their social media for a particular show.

Volunteers – Like many non-profits, theatre companies rely heavily on volunteers. The Board of Directors themselves are volunteers and legally cannot be paid for their work on the Board. Depending on resources to hire staff, volunteers may also take on a wide range of duties from assisting in the office to ushering.

I won’t outline every staff or volunteer position here, but the charts below provide a good overview. Every company is unique though and their website will usually outline who is on staff and volunteer opportunities.

In general, running a company with a Board, any staff and/or volunteers means having clear job descriptions, regular ways to evaluate, excellent communication from all involved, and an understanding that the mission of the company and the good of the company supersedes any personal preference or personal benefit. There is always a need to learn to delegate, but also to have processes in place for accountability. Things will go wrong.

In general, running a company with a Board, any staff and/or volunteers means having clear job descriptions, regular ways to evaluate, excellent communication from all involved, and an understanding that the mission of the company and the good of the company supersedes any personal preference or personal benefit. There is always a need to learn to delegate, but also to have processes in place for accountability. Things will go wrong.

Finally, when we talk about structure it is important to acknowledge how hard it is to find stability as a theatre company. The larger ones will have started at a time when there was a desire to establish regional theatres so they came in at the ground level receiving operational funding from arts councils. Newer companies have to prove themselves for many years before even being eligible for multi-year funding, and have to work project to project without granting support for the day to day functioning.

The Greiner curve and other studies of company cycles explore the general pattern of growth that can lead to the risk of growing too big to sustain, or losing relevance and having to re-imagine or face possible decline. In general companies are grappling with stability all the time, but the last few years have been particularly precarious and restructuring has resulted. Conversations have become about how to engage new audiences, whether productivity can be increased and expenses reduced, how to manage increasing costs, finding models that better serve the arts as opposed to the bottom line, dealing with huge societal shifts, and the loss of skilled workers in theatre who can be paid more elsewhere.

So here’s a fundamental piece that I think not too many theatre students know. Theatres of all sizes and scale essentially operate like a three legged stool. Right? And the three legs of the stool are earned revenue, private sector revenue, public sector revenue. So, tickets and subscriptions, donations and contributions and sponsorships, special events and the public funders. All organizations have a different balancing act of that. Right? They have different sized legs of the stool. So that’s where the analogy falls apart a bit.

But, an organization that does not keep an eye on all three legs is going to find itself in trouble. That structure is what holds up the professionalism of theatre companies. It allows us to pay artists, it allows us to pay staff. It allows us to do things in an ethical way, in a legal way, in a way that is covered by insurance. It allows us to keep people actually safe and cared for and allows us to have the resources to create that safe and caring environment. And so, you know, organizations that don’t recognize that balancing act, struggle. And it’s a good piece for artists to think about, because their role in this is not to be, you know, it’s not to analyze the strength of those three revenue pillars, but it is to remember that if an arts organization asks you to attend a fundraising event and speak, that’s an important part of that organization’s bottom line. And if they ask you to pay for some of the tickets that your family are using because you’ve maxed out on the comps that were allocated, it’s not a micro-aggression. They’re just trying to fill their earned revenue bucket. And if you are fortunate enough to be on a jury, you know a grants jury, you have an incredible role to play in terms of advocating for the organizations that you care for and love, because that will help them be strengthened as well. And so I think that really fundamental knowledge about how organizations operate on a revenue side allows somebody to understand why we might have different kinds of sizes, scales and scopes. You know, I also think that all theatre students should know that most theatres in this country are working under professional standards that are important for us to adhere to, and that they, those professional standards are not intended to be barriers they are intended to be guardrails. Right? So, your experience when you’re working with members of the professional theatres should be a safe experience. And if you’re not experiencing that, you need to say something. – Camilla Holland, Executive Director, RMTC, Winnipeg, MB

If you are thinking of starting a theatre company you need to think through the legal side (whether to incorporate or not), insurance (many venues now require renters to have their own liability insurance), and financial needs. You will want to sort out the governance structure that makes the most sense for you. It is very helpful to reach out to those who have started a company for a chat before you dive in. See the chapters on Theatre Companies and the Theatre Maker track for more details.

The other aspect that influences the size and scope of a theatre’s structure is whether they are venued. In other words, they have their own space and need the staff and infrastructure to manage, maintain, and care for the space. They may rent it out to others. They may host other events. Most of the larger regionals own their own space. Some mid-size theatres lease a space on a long-term basis. Then the smaller or independent theatres are non-venued. They have no space to call home, instead they rent different spaces on a project by project basis and likely run the administration of the company out of staff or company members’ homes.

…a venued theatre is very different from a non-venued theatre. A subscription-based theatre is very different from a non-subscription-based theatre. So, the more you know about the differences between all these things and how they operate, the better it is for you. Whether you are an actor, playwright or director. The more you understand about the inner mechanics of how a theatre operates, but people like talking. I mean, I would say, yeah, what you should know, again, this comes back to asking for help is people are unbelievably generous with their time and downloading their knowledge base. So, if you want to know how PTE (Prairie Theatre Exchange) works, you can always find someone who works there now or used to work there and just say, what is it? What is it that goes on at a, you know, mid-size regional theatre with a venue and that, you know, often you don’t know what you don’t know, but you’d be surprised.

If you just start the conversation, then you’ll realize, oh, you have collective working agreements with unions. What’s that? How does that work? Oh, you have, you know, part time staff and full time staff. How does that work? How does employment, whatever area it is. How does, how does, you know, Thom Morgan Jones pick a season? I’ll bet you if you asked him, he’d tell you. But then you learn about the idea of curation. And what does it mean to, to choose a season. What does it mean to choose a season when you have more than one space, like at the Arts Club? And why does something go at the Hirsch and something else goes at the Warehouse? What are the factors that influence those decisions? You know, these are all learnable things. So, what should you know? As much as you can know and how do you know things you don’t know? Just talk to people. – Jovanni Sy, Montreal, QC

Volunteers

Since volunteers are the backbone of the non-profit world this is an entire aspect of a theatre company’s structure to consider. You have to think about how to recruit, incentivize, manage, and train. So many times I’ve had someone say just get a volunteer to do that, as if that would save time and effort. However, it is never that simple. Good volunteers are worth their weight in gold.

Activity: Do you volunteer? What would be an incentive to get you to volunteer or keep you volunteering?

Some common incentives include:

- Fun

- Social experience with great people

- You love the organization and are motivated to help them

- An educational opportunity where you can learn or try new things

- Training that might assist your own professional development

- Networking

Volunteer Management is an entire field of study. Most volunteers tend to be either seniors who have the free time or students who are doing it for credit or to build up their resume. There are many regional organizations that support volunteerism and can help with recruitment (for example Volunteer Manitoba).

Again clear communication is crucial with strong outlines of each task or volunteer position as well as specific expectations and incentives. You need to find good fits and also to have a constant flow of new volunteers as there will always be turnover. In addition, volunteers can be your company’s cheerleaders and community advocates talking you up within their circles.

You do have to think about who will supervise or oversee each volunteer so they feel supported, engaged, and can actually do the work in a way that helps the company. Sometimes it is good to ask if it is worth the investment of resources to have volunteers in certain roles. Some volunteers will be happy to stuff envelopes and others will find this not rewarding enough. However, to get volunteers doing something more complex may take a great deal of staff time to orient and train, so you’ll want to make sure the volunteer will stick around for the long haul.

Volunteer Resources:

Canadian Knowledge Hub for Giving and Volunteering

Volunteer Management Professionals of Canada – VMPC

CHAPTER SUBSET – BOARDS

As noted, since most theatres are non-profit and often charities, they legally must be governed by a Board of Directors. These volunteers are professionals who are there to steward the organization – basically allow it to meet its mandate in a fiscally responsible manner. They are meant to put the good of the organization before anything else. However, many on the artistic side struggle with the idea of an outside party (generally made up of non-theatre workers) who usually have the power to hire and fire the leaders of a theatre company. Some companies are choosing to find new structures, including not incorporating as a non-profit to avoid having to answer to a board and funders. The other challenge with Boards is their lack of diversity, due to the pool of professionals who have the time and economic stability to volunteer.

The Board generally focus on strategic goals, hire the leadership team, regularly receive reports on programming and budget to make sure goals are being met and there are no areas for concern, assist in fundraising, and are advocates in the community. They are not intended to be involved with the day to day operations or directly interact with staff other than the leadership team. With smaller theatre companies who do not have staff support, the Board may be more of a working Board participating actively in operations.

Legally a Director or Trustee (who make up the Board of Directors) must act with:

- Diligence. Act reasonably and in good faith. Consider the best interest of the organization and its members.

- Loyalty. Place the interest of the organization first. Don’t use your position to further your personal interests.

- Obedience. Act within the scope of the law. Follow the rules and regulations that apply to the organization.

Although it is American, The Art of Governance: Boards in the Performing Arts edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead is a great resource as it speaks specifically to the unique position of a Board of Directors for arts organizations. A very different reality than someone on the Board for the Red Cross or UNICEF.

The board of trustees holds the theater in trust for the community. That trust includes responsibility for maintaining or strengthening an organization’s financial position. The board is also responsible for maintaining the balance between the desire to invest in the highest quality programs and the responsibility to sustain financial integrity.

One of the key roles of the board is to help determine the theatre’s priorities on both an annual and long-term basis. Understanding the financial position and financial trends of the theater allows trustees to more fully consider strategic issues they will confront.

– The Art of Governance: Boards in the Performing Arts edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead (p. 183)

Having informed Board members who understand the role of a Board, governance, and the reality of operating a theatre can be a challenge. Often staff have to dedicate time to orienting, training, and managing the Board or ideally the Board creates a process to have experienced members do this for new members as part of succession. The traditional advice has been to have an accountant and lawyer on your Board or at least those who are versed in these areas. This is suggested because often artists do not have financial and legal training and the company may need this support or advice. Everyone on the Board should at least learn how to read and understand financial statements since by approving these a Board member becomes legally responsible. Larger theatre companies might be able to hire accountants and lawyers, but most employ or contract a book-keeper and hope to never need to pay for legal representation.

Of course there have also been many cautionary tales over the decades in terms of Board overstepping, or on the opposite end of the spectrum not noticing discrepancies whereby staff were putting the company at risk. Board liability insurance has become something many will insist on just to sit on a Board. This protects them from being held personally responsible financially if things go wrong. In general, particularly with recent societal shifts and calls for greater social responsibility, it is a lot to ask of a group of volunteers. There are consultants, workshops, and training all focused on creating better Boards and Board experiences. How to protect a theatre company from a Board not acting in its best interests is a harder conundrum and comes back to the very dilemma of whether a Board is the right governance model.

“Like Juliet, boards of trustees, search committees and artistic directors throughout America are searching for a serious partner (to produce), a dedicated lover (of theater), and a Romeoesque or Julietish leading player with the training, diligence, charm and willingness to fight and strategize for their mutual long-term benefit.

Since the job description for most managerial openings in professional theater might be summarized as a search for someone with the patience of Mother Theresa, the financial wizardry of Warren Buffet, the vision of Superman, and the resilience of Hillary Clinton, it’s little wonder that ideal candidates are few and far between.”

– How to Run A Theatre by Jim Volz (p. 49)

Since the Board plays such an important leadership role, it requires a strong lead in the role of President or Chair. They will:

- Set realistic meeting agendas with clear action outcomes

- Be well-versed in whatever procedural model is used (for example Roberts Rules of Order – (cornell.edu))

- Have strong communication skills to navigate the flow of information both between Board members but also the staff leadership team to and from the Board

- Work closely and cooperatively with the staff leadership team, ideally supporting them rather than creating more work for them

- Deal with Board issues from interpersonal conflicts to possible public relation issues

It’s the sad truth that the performing arts are full of glory hounds and people with hidden agendas. There’s really no way to make your organization 100 percent impervious to these kind of people, but you can keep self-serving and destructive behavior to a minimum by creating a clear chain of command for your organization. If you know who’s responsible for what, then you know who deserves praise and who doesn’t. Along with this concept comes the simple issue of respect.

– How to Start Your Own Theater Company by Reginald Nelson (p. 117)

In my view, a strong, mutually supportive working relationship between board members and artists and management is vital to the success of our not-for-profit theaters. For me, this means board members not only being successful in fundraising, planning and finance, but also understanding the deeper nature of art – how it is created, who creates it, what the risks and rewards are.

…the process of creating art is a series of uncertain steps, and not even the most talented experienced artists can know in advance where the steps will lead. For trustees, this creates a unique kind of risk that makes traditional approaches to governance too simplistic. All organizations – for profit and not-for-profit – operate under conditions of uncertainty but, in the performing arts, there is a difference. In the performing arts, uncertainly comes not only from the external environment in which any organization operates; it comes from within the production process itself. It is the creative process itself that causes the uncertainty. Whether an organization produces a well-known classic or a new work, it never knows how successful the production will be.

– The Art of Governance: Boards in the Performing Arts edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead (p. ix)

How to find good Board members?

- Start by defining their role, e.g. will it be a working board, governance board, fundraising board…

- Current Board members are great assets in finding new Board members as they know what is needed. However, this can also lead to an insular recruitment process once again preventing diversity and wide community representation.

- Make sure it is a good fit, expectations are clear on both sides, and you can provide them with any training or support they need.

- Recruitment process can include an application, interview, observing a Board meeting, contract and orientation.

- Have an initial meeting and go over all expectations before committing, then repeat this information at the orientation.

Names are suggested, abilities weighted, attributes tested against what the board and the theater need. The question is not only: “Do we need a lawyer?” but more fully, “What lawyer has the ability/interest to understand our mission, our culture, our style of governing?” The point is not to fill empty seats. Apart from your artistry, your board members are the public and personal face of your theater. Their quality mirrors your institution’s quality.

– The Art of Governance: Boards in the Performing Arts edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead (p. 135)

A few other considerations that might help everyone to understand the challenges:

- The organization needs to constantly be thinking about succession planning and on-going recruitment as the Board turns over every couple of years (on average a 2-year term). This is added work for the staff.

- You need stability and institutional knowledge with experienced Board members, but term limits can also help to prevent stasis and diversify voices at the table.

- Although not every Board member needs to be an expert at financial planning, they need to know and understand the money side of things from a theatre point of view. Where is the money coming from? How much needs to be raised each year? What is the money funding? What is the staff capacity?

- Boards are often involved with evaluating organizational risk and making decisions that will help to minimize it. However, theatre is by its very nature about risk and can suffer if being viewed through a lens of a sure bet investment.

- If a Board member is just interested in having their name associated with the organization they may be dead weight and a challenge to even get to meetings. This can affect quorum and morale.

- All Board members should have a shared belief and passion in the organization mission and vision. They are there to serve the mandate not their own agenda.

- In a company’s by-laws, there should be a process outlined for removing a Board member in case that becomes necessary. However, in many cases if things aren’t working out a chat between the Board President and the problem member can either resolve the issue or result in a friendly resignation.

Activity: Think about what the pros and cons might be with the Board of Director governance model. How can you get the most from a Board who bring other life experience to the table? How do you prevent a Board from micromanaging? What might be a better organizational model for a theatre company?

Despite experiencing many challenges as an Artistic Director, I was able to work with a cross-section of amazing individuals who I would never have had the pleasure of engaging with if it had not been for their work on my company’s Board. They did bring ideas and experiences from outside the theatre world that I was completely embedded in and this had many advantages. However, there are many horror stories, often due to a lack of a strong artistic focus or a good working relationship.

Board as Advocates

It’s no longer enough to be a supporter in order to warrant a place on an arts board. Now arts boards service means being at activities on behalf of the organization… I would challenge every board to embrace, without reservation, its role in advocacy – to recognize that they have the power to speak and to make the cultivation of relationship with legislators and potential legislators a serious priority. – Ben Cameron, former Executive Director of Theatre Communications Group

A Board is also expected to play an active role in advocacy. They are a theatre company’s fan club, spreading the word, but also have a role to play in advocating for greater support for the arts. This includes convincing others of the value of theatre, including potential partners, sponsors, government, and donors.

Every so often the Board of the company I led would take time to write their own elevator pitch about why they choose to be on the Board of the company. It was basically one story they could tell about the value of the company for them personally. Often it included their most memorable experience with the company. They’d share these with one another at a Board meeting. It was a great exercise not only to prepare them as advocates, but it reminded everyone why they were at the table. It is important to remember the impact of the work as it can become very removed from the business at Board meetings.

Trustees should also be willing to fly the flag in the community (or grow to become comfortable doing that), with little signs on their chest saying, “I am a trustee of this theater company. You can talk to me.” Basically, I’m here as a warrior for this cause and not just as a kind of affiliate because it’s slightly glamorous. I’m here to fight the good fight. – Ben Cameron, former Executive Director of Theatre Communications Group

Board as Financial Management

As noted the Board also has a financial management role. They have a responsibility to make sure the company is being fiscally prudent and meeting financial goals linked to the strategic plan. They can provide continuity by looking at the long-term financial plan and comparing year over year shifts. They approve the budget presented by the staff and should do their due diligence by asking questions, making sure it is realistic, aligns with planned activities, as well as external realities such as inflation.

There is also a financial reporting system so that the Board can regularly verify that things are on track. This may be with regular meetings with the staff who oversee accounting and the Board Treasurer. It is up to the Board to decide the financial reporting system that will be used. Most non-profits require a Board Executive member to co-sign cheques, approve expenses above a certain amount, and even to verify the regular payment of source deductions from employee pay to CRA. Quarterly financial statements are usually reviewed by the Board Treasurer and then presented to the full Board. They will then also approve the year-end financial statements, having appointed an auditor or review engager (an audit is generally required by CRA and funders if your budget is over $500,000 and a less intensive review engagement by an accountant can be done for those with smaller budgets). The Board will also actively assist with activities to bring in revenue and make sure goals are met. They approve/monitor any investments or larger assets of the organization. They often also make a financial contribution of their own with an annual donation. Although it is important to note that this requirement can again limit who is at the Board table.

Our interviewees had a lot to say about Boards:

I will admit that I’ve had really varied experiences with boards. That was one of my conditions when I started at Western Canada Theatre that I didn’t have to deal with the Board and about three or four years in, David said, you know, that’s got to change. And I do know people who say, like, who will come and work in a position like a second in command so that they don’t have to work with the board. I have also had amazing experiences with board and knowing that the knowledge as I say, much of the legal knowledge was management knowledge, marketing knowledge, knowledge of the community. It’s a place where that knowledge can really reside and inform the work of the organization.

I have certainly always worked with all of my boards to set up really clear processes in cases, in 95% of the cases I’m going to say it’s an ED to president line of communication. No other interaction. There may be a few committees like Fund Development where there’s a more direct communication. But making sure that the board understands what governance is and your role as the director and the staff to understand, you know, what their role is and that line of communication. And I think that those are the structures that I have enforced in very challenging situations. In an ideal world, people can for sure be together and exchange ideas. And so any role – that relationship with the board and the ED, if it’s the ED and the AD whatever that relationship, is really important; is really critical. Having a role too, in board recruitment, having clarity in terms of the mission, having clarity in terms of roles and responsibilities. You know, because you can have a working board as well as a governance board. But that clarity is absolutely essential to a good working relationship. – Lori Marchand, Managing Director, NAC’s Indigenous Theatre, Ottawa, ON

I think it would be fair to say that theatre, and I’m sure other nonprofits, profits as well, but theatre around the country since a long time is riddled with good boards and boards that aren’t so good. It’s really been a lot of people over a long period of time often find themselves on the other end of their own theatre company because someone decided they were going to change it. Right? And I think I do think that anybody and I’m not saying all bad, like I said, there’s lots of positive things, too. But I think it is something, that you have to think about if you’re going to run a company now, not so much if you’re going to, you know, but maybe even if you’re not, you need to think about who’s your relationship going to be with, you know, and what’s the role of the people that are in the management of the company versus the people that are the board? And what’s the role of the board? You know, and all that’s becoming more and more, I think, you know, stronger and stronger and more and more issues these days for big… because of a lot of the things that are now happening about workplace and all that kind of thing. So, I think it would be important if you had an interest in a company to really do a lot of looking into that and thinking about it and thinking about what kind of relationship that you might have and is that going to work for you. Is the big difference in running a small private business and a nonprofit. There’s a lot of similarities, but there’s but there are differences because of that board structure. – Donna Butt, Artistic Director, Rising Tide Theatre, Trinity, NL

In the simplest terms, the board of directors is there to set policy. And to make sure that policy is adhered to. But they hire the leadership in most theatres. It’s usually a two-pronged leadership structure, the general manager or managing director and the artistic director. And those are the people that liase directly with the board. Everything is supposed to flow from those two people down. So, in a well-formed board structure, there shouldn’t be a lot of interaction between staff and board. Then again, in very small organizations where it’s a one- or two-person shop, often there will be board members who are necessary to take on more of a hands-on approach. They’re almost fulfilling some staff roles that the organization is not able to hire for. It can be tricky, because there is that balance that the board members are volunteers, not paid staff. Also, if the board has not been given a proper orientation, or if you have a board president who doesn’t really understand that they are not the bosses of the staff, then you get some tricky situations. The board can also be called on to form committees that are there, in an advisory capacity, often for marketing and development. So, they should be there to support the staff’s efforts. They should not be directing the staff’s efforts. – Haanita Seval, Director of Marketing, PTE, Winnipeg, MB

But the way companies work, board structures and such, I think there’s a shift happening right now where the models that have been sort of inherited are being pushed back against. So some companies like our company, we’re in a, I think we have a capacity building grant right now to work with consultants to look at how can the values of Arrival’s Legacy Project be also filtered into the organizational structure? Do we have to do that, you know, tried and true structure of board, general manager, artistic director, or is there something else? Is there another way of working? I’ve been working with a company called Pangea World Theater and Art2Action. They’re two companies in different parts of the US that are collaborating on new models of partnerships so that they have a training institute, national institute for directing and ensemble creation, and they bring together directors from across the country together to work together and to study and to develop our practice. And mostly racialized Indigenous directors. – Diane Roberts, Director/Dramaturge/Cultural Animator, Montreal, QC

I’ve seen artistic producers who want the board to have nothing to do with anything, and they want them to stay in their room. And then I’ve seen other ones that bring them into rehearsals and they’re everywhere. And I really think that if you’ve got a board, you should make use of them and welcome them into the family. And so, it’s not just them in a room making decisions, but that they have a better understanding of the actual working. I think that’s really important. – Ricardo Alvarado, Stage Manager, Persephone Theatre, Saskatoon, SK

Additional Resources on Structure and Governance

For fun:

Shit Nonprofits Say – Twitter (X) @nonprofitssay

- Our 4-page transparent decision-making matrix can be summarized this way: Our ED will make all decisions, regardless of your input.

Cited and additional resources on the discussion of new governance models:

- ‘Governance structures for theatres, by theatres’ by Yvette Nolan – Mass Culture • Mobilisation culturelle

- Nidhi Khanna on Reframing Governance — Generator (generatorto.com)

- Governance Reimaginings — Generator (generatorto.com)

- Our new tri-leadership structure – Theatre Passe Muraille

- Should arts groups be run by corporate-style boards? (thestar.com)

- https://tift.ca/service-projects?tab=arks

- https://www.balancingactcanada.com/

- Boards Are Broken – American Theater Organization

See Changing Theatre and the Future of Theatre