9 Funding and Grants

Funding and Grants

“Institutions don’t die from a lack of meaning, they die from a lack of funding. It’s we who die from a lack of meaning.” – Dave Hickey, American Art Critic quoted in Theatre of the Unimpressed by Jordan Tannahill (p. 75)

The reality is that the arts are very difficult to fund and resources are always limited. In the theatre realm, ticket sales (especially if they are reasonably priced) will never come close to covering the full cost to produce a play, let alone to operate a company offering a season of work. This is why there are few commercial producers in Canada; it is really hard to make money producing theatre. In the States, many commercial theatre investors do it for the tax break knowing they may never see their money again. Or maybe, it’s the thrill of the gamble – there is a chance you’ll back the next Wicked.

So, the standard non-profit model we see in Canada means a constant and time intensive effort to pursue funding. Even the independent producer generally has to put a lot of work in to finding revenue to cover the costs of doing a single show.

There is a misconception that the arts are highly subsidized by the government. Although there is government funding, it is nowhere near enough to cover actual cost. In fact, pre-COVID, in Canada based on taxes and funding for culture, arts, and heritage most Canadians contributed just $29 annually. In the United Kingdom this figure was closer to $83 and in the U.S. it was just $0.42. Unfortunately, the UK was starting to move away from public funding, so this is a trend to watch.

What financial support exists?

In Canada, we support the arts using what is sometimes called a “mixed” or “balanced” model. This means that non-profit arts organizations rely on a combination of public, private, and earned revenues. This model has been described as sitting between the primarily state-sponsored arts and culture of European countries like France, and the free market, privately-supported model in the United States.

– A Balancing Act: Supporting the Arts in Canada | The Philanthropist

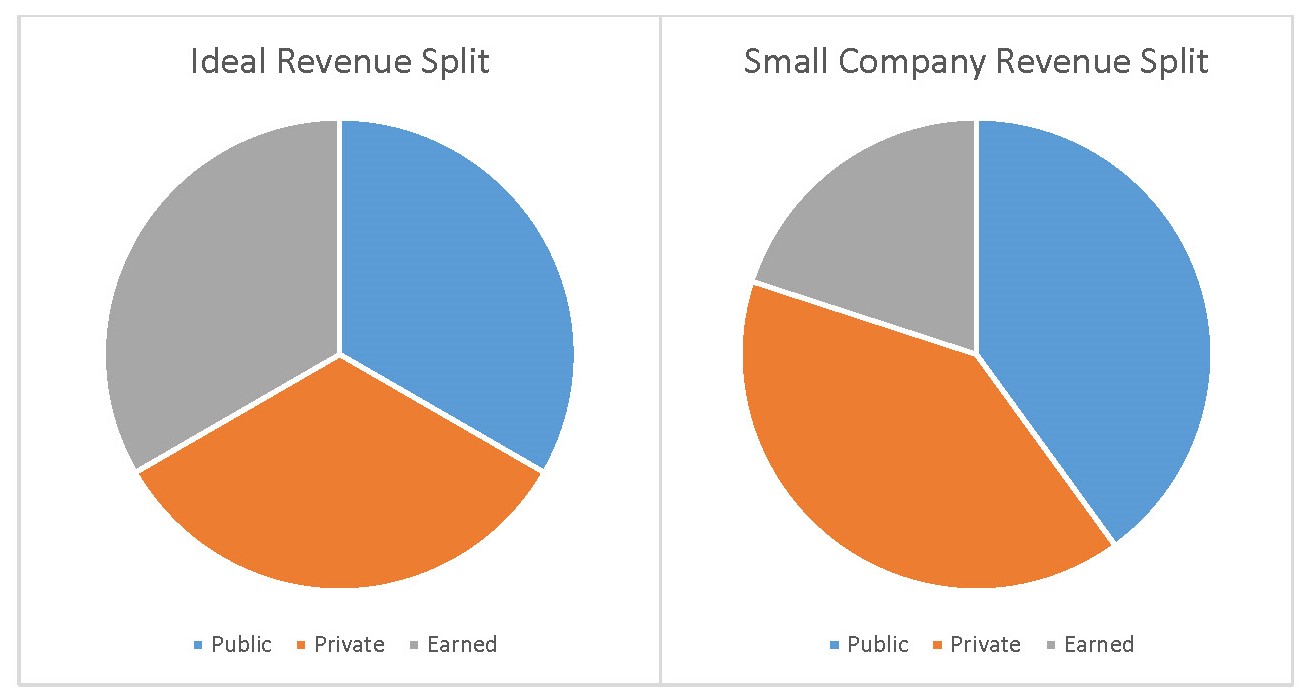

Earlier in the book a stool analogy was used, it can also help to think about it as a pie with three slices. One slice is public (government), the second is private (donations), and the third earned. Ideally the three are even but often for smaller theatres with fewer seats, earned revenue is much less than the other pieces. It will vary though from theatre to theatre. Funders like to see that you have diversified revenue, meaning you are getting income from many sources. This shows a range of support for the work but also that if one pot were to disappear you could still carry on.

You will hear public funding referred to as grants. The federal government, as well as some provincial and municipal governments, offer granting programs for the arts. These programs are generally there with a mandate to support local artists, a healthy cultural ecology, and the greater good of the communities they represent. Outside of art specific support, you may also be able to apply to other government departments or programs. Due to the topic of a play, I’ve been able to access human rights funding, grants from the Status of Women for community arts work, and even funding through Canada Summer Jobs to support student production assistant positions. Mostly though, theatres rely on arts councils that are specifically set-up to fund the arts with an arms-length model. Here the government provides a set amount of funds to an arts council who then distributes the monies by setting up peer assessment panels to evaluate applications. In this way the government has no say in who gets the money. Political bias is removed and artists are assessing other artists.

- Federal

- Canada Council for the Arts is the federal arts council. It has multiple programs for individual artists, ad-hoc groups, organizations and for various art forms, including specific programs for Indigenous artists.

- For festivals and cultural events there is also the Department of Canadian Heritage.

- There are also employment programs such as Canada Summer Jobs and internships through Young Canada Works.

- Depending on the focus of the work there are also possibilities such as the Status of Women, Climate Action funds, and Anti-Racism programs.

- Provincial

- Many provinces have an arts council, for example in Manitoba there is the Manitoba Arts Council.

- There is also possible alignment to other provincial departments, for example Manitoba Building Strong Communities and Manitoba Economic Development.

- Again, there may be particular programs that align with the content of a show and provincial funds for internships or career readiness.

- Municipal

- Some cities have their own arts councils.

- I’ve also received funding from municipal recreation departments to support theatre work with youth.

PRIVATE

This refers to various funding pools that are not connected to the government or public tax dollars. The income comes directly from individuals, corporations, or foundations.

Fundraising

We spend a lot of time fundraising in theatre. This basically means asking for financial contributions. In the commercial world this would be an investment, and in the non-profit realm a donation.

Professionals train to become experts in how to raise funds, how to develop relationships, and cultivate donors. You need to constantly find new contributors. At the same time, you need to keep existing donors happy by stewarding or strengthening their engagement. Ideally this will lead to an increase in their investment over time, up to and including having them include a contribution in their will.

Some companies hire staff specifically for this work, or contract professional freelancers. Many cannot afford to do so and it is either added to the tasks of other staff or the Board becomes actively involved in fundraising initiatives with staff support.

Ultimately part of a Board role is to assist in raising funds, often forming committees to put on fundraising events or galas. They may also bring new people to the theatre as ticket buyers, subscribers, or donors. Some Boards have a give or get policy where they are asked to donate a certain amount or raise it. Larger companies also often will ask their Boards to purchase a subscription. By doing so the Board demonstrates a commitment so that when they pursue other donors they can honestly say that they have given themselves.

Fundraising events are often part of the mix (galas, raffles, golf tournaments, lawyers putting on a show…) and can both raise money and provide exposure. However, the effort and time invested needs to be weighed against the potential earnings. I’ve seen many fundraising events that cost a lot and once the staff hours were calculated didn’t actually raise funds.

If you are putting on your first Fringe show, then your fundraising may simply be asking friends and family to each contribute.

Donors

Activity: Ask yourself have you made a donation – why and to whom? Were you thanked?

Like so many other things, soliciting donations is about developing a relationship. It is important to identify a fit, make a personal ask, and then steward that relationship with a real gesture of gratitude. Just think about how you feel when you get generic asks that are clearly a form letter just because you attended one show one time. Even more annoying if you gave a donation and were not thanked, but then received multiple more requests. Research shows there is value in finding unique ways to thank every contributor, and to do so for each contribution.

Again, donor relations are time consuming. It includes building a donor list, coming up with a donor cycle so there is a regular schedule for approaching and engaging donors. You also have to be clear about what the need is, tell a story, make it specific and follow-up with results.

There are several different styles of campaigns or asks:

- Annual Campaign or Annual Fund

- Launching a large campaign once a year to meet your budget needs

- Generally, there is an existing list of donors who contribute annually and you approach them as well as new potential donors who have engaged in some way with the company over the past year

- Direct mail

- Writing a strong letter to send to your mailing list a couple times a year

- Phone

- Volunteers, staff and sometimes even Board members will call past donors, ticket buyers, or those on a company’s mailing list to pitch both ticket sales and/or donations

- Curtain Speech

- Some feel it is effective to make an ask directly to the audience while they are there and hopefully excited about the work

- Others find it crass when they’ve already just paid for a ticket

- Doing it in the right way is crucial

- Endowments

- This is a fund set-up with investments so that the core amount put in is never used, but the interest generated is spent

- Some donors really like the long-term focus this provides and that their donation will last forever

- e.g. Winnipeg Foundation MyCharityTools | Pick a Fund

- Planned Gifts

- These are planned in advance and then left as part of someone’s estate/will when they pass

- Major Giving

- Some level of engagement with the theatre is usually part of this due to the large amount being donated, so you may see a rehearsal room named for the person

- What is considered major giving depends on the company and what they see as a large contribution, but generally we’re talking about tens of thousands

- Capital Campaigns

- These are for major building renovations or large purchases where you might launch a specific high-profile campaign

- The challenge is not to siphon away contributions from your annual campaign (what existing donors already give each year), as you may need these for day to day operations

- Crowdfunding

- Generally, only used by independent companies or those self-producing a specific show

- Need to think of the various benefits you can offer such as signed posters, t-shirts, a special reception for those who contribute, or a meet and greet with the artists

- Research is required as many of the on-line platforms charge fees and offer various levels of support

Statistically face to face and personal approaches are successful half of the time. A phone call works a quarter of the time, as it is easier to say no to someone by phone. Letters have the lowest return at 10-15% as they are less personal.

It is important that the time to do this work is acknowledged. It requires time to process and manage charitable tax receipts, accounting, thank-yous, periodic reporting to share the outcomes, and just maintaining relationships.

Foundations

These are charitable entities generally set-up by individuals, families, or corporations as a means to manage their charitable giving. As they are registered as charitable foundations, they have to distribute funds to qualified donees (other charities). The benefit to those who set these foundations up are the tax break for the funds they provide to the foundation to distribute, a streamlined way to funnel donations, and creating a legacy. There are hundreds of foundations, and the time-consuming part of accessing them is researching for specific areas of interest to make sure there is a fit before pursuing things any further. Some only give to specific charities and don’t accept requests, others give only to a narrow focus. Few give specifically to the arts but if you are doing a show about a topic, you may be able to pitch it to foundations interested in that topic. For example, when working on a show addressing climate change you can approach foundations who have as part of their mandate supporting climate action. Generally, you will start with a letter of inquiry and then a full application. Again, this is an investment of time, so it’s always important to do the research first to make sure it is a fit and that you know what they are looking for in terms of an application, as well as timeframe to submit.

Then there are also final reports to write, tracking of approaches, follow-up…a labourious process.

For more details on both public (corporation-based) and private (individually-based) foundations: Types of registered charities – Canada.ca.

Sponsorships

The other avenue is sponsorships. Here a business or corporation makes a financial investment in return for a promotional benefit. You need to find a business that is a good fit or whose values and strategic priorities align with the theatre company or the focus of a specific show. This is also about developing a relationship with contacts at appropriate businesses. Many businesses tend to give to the same places year after year, as long as they are happy with the results. Learning how to write a strong proposal, get a meeting, and cultivate a relationship is important. Those doing their first approaches might make the mistake of starting with the ask for a specific dollar amount. Ideally, you start by building a relationship and figuring out an affinity as well as an amount that is feasible for the potential sponsor. Ultimately, sponsorship work results in a lot of declines, but not asking will result in no support so a strong ask is at least worth a shot.

There are of course also challenges around what businesses you might want to align with based on your values, which can sometimes lead to hard conversations. If your theatre tackles the topic of climate change, then accepting an oil company sponsorship may not feel right or be good optics.

Business / Arts provides training and resources around arts investment.

Most businesses use their marketing or community engagement budget for sponsorship so are looking for some bang for their buck. They don’t just want to support a good cause but want folks to know they are supporting a cause. This means thinking through clear benefits based on level of sponsorship. Will their logo be on the poster? Will there be a special reception for their employees? Don’t give away the world, but make sure the value aligns with the benefit.

Creating a strong package and support materials is important. Everyone in the company involved with fundraising should have access to a strong company overview, company history document, and an outline of funding needs. Writing and updating these materials is an investment of time. You will also need time to do periodic check-ins and send a final evaluation of the initiative, including numbers of people who attended or were impacted.

In-Kind

There is also an option to have in-kind donations. This is where goods are donated rather than dollars. Advertising sponsorship might be in-kind, whereby a media outlet (radio, tv, newspaper) provides promotional support rather than cash. Some companies might donate computers or furniture. Another theatre company might offer you in-kind support with free rehearsal space. These items are still reflected in budgets but outlined as in-kind. This makes clear what the true expenses, resources, and needs were even if some of them were donated items.

A charity can provide a tax receipt for an in-kind donation, however the CRA requires there to be proof of the fair market value of any goods. You can’t just decide what the worth is, but must be able to demonstrate how the valuation was decided to prevent folks receiving inflated charitable tax receipts.

Finally, it is important to differentiate between a donation and sponsorship. Since a charitable donation is given as a gift, it cannot come with a tangible benefit. If a company wants their logo on the poster or other promotional benefit, then this is a sponsorship and a charitable tax receipt cannot be given since it is therefore not a gift or donation.

EARNED REVENUE

This includes a range of components through which a company or an individual show might earn money:

- Box office (ticket sales which includes subscriptions)

- Merchandise (t-shirts, programs)

- Advertising (program ads, website ads)

- Workshop Fees (if you offer workshops or classes)

- Membership (some companies have a membership )

Activity: It is an interesting exercise to look at the budgets of theatre companies you are interested in, frequent, or even might be approaching for employment. Many have their annual reports on their websites with an overview of their financials for the year. Can you find a few examples to review?

Below are just a few examples:

ABOUT – MTYP – Manitoba Theatre for Young People p. 29

Royal-MTC-2021-22-annual-report-web.pdf.aspx (royalmtc.ca) p.14

Nightwood Theatre Annual Reports and Audited Statements

You can also look at various campaigns as examples of how companies provide benefits and outline details of their needs:

Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre-Individual Giving (royalmtc.ca)

Friends-Benefits-colour-2020.pdf (pte.mb.ca)

For more legal information check out Charities and giving glossary.

For companies, there are many funding needs outside of the hard costs of production, for example:

- Additional staffing

- Programming such as workshops or community outreach initiatives

- Accessibility

- Training and education

- Overhead costs, especially between shows when there is no earned revenue

- Contracting experts or consultants

- Marketing initiatives that requires an investment in order to earn box office revenue

- Capital costs such as building and equipment

Ultimately everyone involved with a theatre company or a production should be involved with fundraising.

Even if you never plan to have to secure funding, this should give you a good idea of how much work goes into this side of things. Theatres and producers have to work very hard to find the money to just put on a show!

Commercial Theatre and Investors

Just a bit of context for commercial theatre, when seeking investors a lot of the same things apply in regards to building relationships. A few tips:

- Let people know about the project by talking it up to everyone, calling all your contacts or getting recommendations of people with money

- Get them excited by sharing your passion for the project

- Have a clear plan and pitch for how they will see a return on their investment

- Cultivate relationships with investors through a reading or showcase

- Keep them informed and excited along the way

More on Grants

In theatre, as noted in our initial survey and by many interviewees, learning to write a strong grant application is a very valuable skill. Taking workshops on grant writing, talking to officers at arts councils, asking to see successful grant application examples from colleagues, and asking questions is all good advice.

I regularly have members of our municipal and provincial arts councils come speak to my classes. Many of the arts councils also host information sessions. Here are a few take-aways from what these staff members have shared:

- Sadly, due to limited funds to distribute the success rate is often just between 15% to 30%. (Side note: Having sat on many assessment panels I can honestly say there were many great projects we wanted to fund but there wasn’t the money.) A panel will rank the applications and once the funds allocated are gone those below the line do not get a grant even if they were deserving.

- Check the website for criteria and do not waste your time if your project is not a fit.

- Once you have read through all the information, contact the listed officer for a specific grant and have an initial conversation to make sure you are eligible and that what you are planning fits, also to get advice. Most councils will also allow you to send a draft in advance for the officer to review for any issues.

- Be clear about the deadline and that your project dates fit within what is allowable.

- Start early and make sure you have everything that will be required – forms signed by the appropriate person, letters of support, support materials, researched budget numbers, bios and resumes…

- Consult your team. If you are listing someone as a collaborator make sure you are on the same page.

- Allow time to thoroughly proof read the complete application, or even better get someone else to proofread. (I can never see my own typos!)

- Most applications are on-line now, so you can submit them just before midnight, but bear in mind staff won’t be available to help after work hours.

- As noted, Arts Councils are arm’s length and peer assessed. You therefore need to convince other artists, sometimes those in theatre but other times those who work in other artistic mediums. Make sure you present a strong but clear argument.

- Most grant applications allow support materials that are meant to demonstrate either your past artistic work that relates to this project, or the strength of the project itself:

-

- You want materials to be high quality. You can include videos and photos to show the caliber or style of production as opposed to just the script, but make sure the video and photos are strong or they might work against you.

- You can also include reviews, letters of support or testimonials.

- Samples of writing or past work are good but make sure it demonstrates strength and ties in to this particular project.

- If sending a work in progress, be clear about where it is at in the process so it can be reviewed with that in mind.

- In terms of resumes, you want to focus on showing your ability in the area that is most applicable to the grant, but you can also include information that shows the breadth of your experience.

Written Application tips:

- Write for your readership

- What would be the difference between writing a grant for other theatre artists to evaluate versus a multi-disciplinary jury?

- Speak specifically to the criteria in your application

- Clarity is the most important thing (detail the 5Ws + How)

- Clear logistics are important, an assessor must understand exactly what will happen, when, and how

- Avoid grant speak

- Talk artist to artist, communicate your vision, goals, plans to another artist

- Speak peer to peer directly and honestly

- Avoid academic language

- Like all submissions, be sure to use strong, concise, and active language

- Avoid run-on sentences that are hard to follow

- Focus on artistic merit, why this project, and why now

- It is difficult to sift through highly conceptual language

- Remember an assessor might be reading 100 applications, make it easy for them

- Each part of the grant application should align and support the ask

- Answer all questions and provide information required

Application Budget tips:

- It is not a strength to show cheapness in the budget

- Always look at the industry standard or explain why fees are lower than the standard

- Remember to pay yourself in a budget if you are working on the project; or in an individual artist grant part of the goal is to be able to cover your living costs while you focus on creating your art

- Be sure to include the grant you are asking for as part of the outlined revenue

- In-kind components must balance on both the revenue and expense side

- Include the breakdown of box office revenue and artist fees

- How much are tickets, how many shows, and how many tickets per show?

- How many actors, how much is each making overall or per week? Make sure this is clear so the assessors can tell it is realistic and equitable.

Many complain that they spend more time writing grants and reports than actually doing their art. It is a balancing act for sure. It also takes time and experience to get better at it. Many artists I know took several tries before their first successful grant application, even really acclaimed artists who didn’t know how to communicate the strength of their work. It also depends highly on who is on your peer assessment jury and what knowledge they bring to the table. As you get further along in your career, being a peer assessor is a great way to really learn about grant-writing.

You got to make sure that it’s worth the effort to find the money. And then you have to be smart. Do the work. Get the grants. How do you get the grants? Well, again, another young colleague just got their first $25,000 grant. She said, I don’t know, I don’t know what I did right. And I said, I do. You did a great application. I sat on 50 juries, 60, 100 juries in my life. When you see a really strong application with everything you need to assess it, you’re looking at a whole bunch of them. You’re like, Wow. Top of the pile. Like, this is a really good application. Smart, succinct. This person has talked to people who know how to write grants. They’re young. Look at how wonderful the, oh, look at this little video clip. Beautiful. Strong work. Oh, cool budget, good timeline, all of that in place. – Denise Clarke, Choreographer/Theatre Artist/ Associate Artist One Yellow Rabbit, Calgary, AB

For other resources and lists of grants check out ArtsUnite’s funding information and specifically their section on Getting the Grant. Toronto-based ArtReach also has a great resource page including a toolkit for grant writing and fundraising.

For further thoughts on the larger question of the charitable structure and how funds are raised, this is a great video: The way we think about charity is dead wrong .