Climate and Environment

California Knew the Carr Wildfire Could Happen. It Failed to Prevent it

by Keith Schneider

#reportinginformation #research #nature #sharedvalues #descriptive #analysis #ethos #logos #kairos #currentevents #systemanalysis #environment #global

On the afternoon of July 23, a tire on a recreational trailer blew apart on the pavement of State Route 299 about 15 miles northwest of Redding, California. The couple towing the Grey Wolf Select trailer couldn’t immediately pull it out of traffic. As they dragged it to a safe turnout, sparks arced from the tire’s steel rim. Three reached the nearby grass and shrubs; two along the highway’s south shoulder, the third on the north. Each of the sparks ignited what at first seemed like commonplace brush fires.

But if the sparking of the brush fires was an unpredictable accident, what happened next was not. Fire jumped from the roadside into the Whiskeytown National Recreation Area, a 42,000-acre unit of the National Park Service. There, it gained size and velocity, and took off for the outskirts of Redding. The fire burned for 39 days and charred over 229,000 acres, and when the last embers died on Aug. 30, the fight to contain it had cost $162 million, an average of $4.15 million a day. Almost 1,100 homes were lost. Eight people died, four of them first responders.

Dozens of interviews and a review of local, state and federal records show that virtually every aspect of what came to be known as the Carr Fire — where it ignited; how and where it exploded in dimension and ferocity; the toll in private property — had been forecast and worried over for years. Every level of government understood the dangers and took few, if any, of the steps needed to prevent catastrophe. This account of how much was left undone, and why, comes at a moment of serious reassessment in California about how to protect millions of people living in vulnerable areas from a new phenomenon: Firestorms whose speed and ferocity surpass any feasible evacuation plans.

The government failure that gave the Carr Fire its first, crucial foothold traces to differences in how California and the federal National Park Service manage brush along state highways. Transportation officials responsible for upgrading Route 299 had appealed to Whiskeytown officials to clear the grass, shrubs and trees lining the often superheated roadway, but to no avail.

At the federal level, the park service official responsible for fire prevention across Whiskeytown’s 39,000 acres of forest had been left to work with a fraction of the money and staffing he knew he needed to safeguard against an epic fire. What steps the local parks team managed to undertake — setting controlled fires as a hedge against uncontrollable ones — were severely limited by state and local air pollution regulations.

And both the residents and elected officials of Redding had chosen not to adopt or enforce the kind of development regulations other municipalities had in their efforts to keep homes and businesses safe even in the face of a monstrous wildfire.

The inaction in and around Redding took place as the specter of unprecedented fires grew ever more ominous, with climate change worsening droughts and heating the California landscape into a vast tinderbox.

The story of the Carr Fire — how it happened and what might have been done to limit the scope of its damage — is, of course, just one chapter in a larger narrative of peril for California. It was the third of four immense and deadly fires that ignited over a 13-month period that started in October 2017. Altogether they killed 118 people, destroyed nearly 27,000 properties and torched 700,000 acres. The Camp Fire, the last of those horrific fires, was the deadliest in California history. It roared through the Sierra foothill town of Paradise, killing 86 people.

More than a century ago, cities confronted the risk of huge fires by reimaging how they would be built: substituting brick, concrete and steel for wood. Conditions are more complicated today, to say the least. But it does seem that the latest spasm of spectacular fires has prompted some direct steps for protecting the state into the future.

In September, California lawmakers added $200 million annually to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, budget over the next five years for fire prevention, up from $84.5 million in the current fiscal year. It’s enough to finance bush clearing and lighting deliberate fires — so-called “fuels reduction” and “prescribed fire” — on 500,000 acres of open space, wildlands and forest.

The U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Department of the Interior also are putting more emphasis and money into prevention. This year, federal and state agencies set prescribed fires to 85,000 acres of open lands, an increase of 35,000 acres over previous years and likely a record, said Barnie Gyant, the Forest Service’s deputy regional forester in California.

In Redding, city officials have agreed to rethink how they will manage the several thousand acres of open land within the city limits.

But if these sorts of solutions are well understood, they have yet to attain widespread acceptance. An examination of the Carr Fire, including interviews with climate scientists, firefighters, policymakers and residents, makes clear that the task of adequately combating the real and present danger of fires in California is immense. And it’s a task made only more urgent by a novel feature of the Carr Fire: its explosion into a rampaging tornado of heat and flames. The blaze is further evidence that the decisions made at every level of government to address the fire threat are not only not working, but they have turned wildfires into an ongoing statewide emergency.

Success will require government agencies at every level to better coordinate their resources and efforts, and to reconcile often competing missions. It will require both a strategic and budgetary shift to invest adequately in fire prevention methods, even as the cost of fighting fires that are all but inevitable in the coming years continues to soar. And it will require residents to temper their desires for their dream homes with their responsibility to the safety of their neighbors and communities.

“We repeatedly have this discussion,” said Stephen Pyne, a fire historian at Arizona State University and the author of well-regarded books on wildfires in the West. “It has more relevance now. California has wildfire fighting capability unlike any place in the world. The fact they can’t control the fires suggests that continuing that model will not produce different results. It’s not working. It hasn’t worked for a long time.”

A Thin Strip of Land, but a Matchstick for Mayhem

State Route 299, where the Carr Fire began outside Redding, is owned and managed by the California Department of Transportation, or Caltrans. For two decades, it has been working to straighten and widen the mountain highway where it slips past 1,000-foot ridges and curves by the Whiskeytown National Recreation Area.

In 2016, Caltrans spent a week on Route 299 pruning trees and clearing vegetation along the narrow state right of way. And as they typically do with highways that cross national forest and parkland, Caltrans vegetation managers let the Whiskeytown leadership know they would like to do the same thing on federal land outside the right of way. The idea was to prevent fires by removing trees that could fall onto the highway, stabilizing hillsides and building new drainage capacity to slow erosion.

“The preferred practices are a clear fire strip from the edge of the pavement to 4 feet,” said Lance Brown, a senior Caltrans engineer in Redding who oversees emergency operations, “and an aggressive brush and tree pruning, cutting and clearing from 4 feet to 30 feet.”

But the transportation agency’s proposal to clear fire fuel from a strip of federal land along the highway ran into some of the numerous environmental hurdles that complicate fire prevention in California and other states.

Whiskeytown’s mission is to protect natural resources and “scenic values,” including the natural corridor along Route 299. Clearing the roadside would have been classified as a “major federal action” subject to a lengthy review under the National Environmental Policy Act. Whiskeytown would have been obligated to conduct a thorough environmental assessment of risks, benefits and alternatives.

Public hearings also are mandated by law, and such a proposal almost certainly would have prompted opposition from residents devoted to protecting trees and natural beauty. And so the basic fire prevention strategy of clearing brush and trees along a state highway never got traction with Whiskeytown’s supervisors.

Brown said the risks of leaving the trees and brush were clear. But he said Caltrans had no way to force the park to do anything.

Whiskeytown officials are “very restrictive,” Brown said. “They don’t want us to cut anything. They like that brush. They like that beauty. Our right of way is basically in their right of way.”

USDA Forest Service officials and land owners discuss sharing stewardship of forests and future forest treatment strategies to recover lands. “Fire” by Pacific Southwest Region 5 is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Tom Garcia, the recreation area’s fire manager, disputed the view that Whiskeytown opposed any kind of brush and tree clearing. “We most likely would not agree with a clear-cut type of fuel treatment,” he said, “but most certainly would have very likely supported a thin-from-below type of treatment activity that reduced the shrub and brush undergrowth and thinned some of trees as opposed to mowing everything down to the ground level.”

The threat posed by issues such as brush along the highway had drawn the worry of a local conservation group, as well.

The Western Shasta Resource Conservation District, devoted since the 1950s to safeguarding the region’s land and water, prepared a report in 2016 that called for more than 150 urgent fire prevention projects around Redding. They included clearing roadsides of trees and flammable grass and brush, constructing wide clearings in the forest, and scrubbing brush from public and private lands.

Just two of the projects were funded, neither of them in the Carr Fire’s path.

Rich in Fire Fuel; Starved for Money

The fire fed greedily on the dry roadside fuel left along Route 299 that day in late July. In minutes, it jumped from the state right of way into the federal park’s thick stands of brush and small trees, and then up the steep ridge of chaparral, pine and oak.

It was the sort of scenario Garcia had been worrying about for years. A 28-year firefighting veteran, Garcia was known in California for being an aggressive member of the school of fire prevention. He advocated brush and tree clearing and lighting deliberate fires to keep small burns from turning into uncontrollable wildfires.

What he lacked was money. Garcia’s budget for clearing, set by senior federal officials, provided just $500,000 a year for clearing brush and small trees, enough for about 600 acres annually. It was far, far less than needed. Garcia estimated that he should be clearing 5,000 acres a year. Given the budget constraints, he decided to focus on what he viewed as the highest risk area: the park’s eastern boundary closest to Redding’s expanding subdivisions and outlying communities. Garcia took a chance; he left Whiskeytown’s northern region, the forest farthest from Redding, largely untouched.

The risk was significant. A decade earlier, a fire had burned 9,000 acres in much the same area. By July 2018, the land had recovered and supported a new fire feast: Manzanita, oak, small conifers and decaying timber, a dry mass of fuel ready to burn.

Garcia was deeply frustrated. Clearing fuels works, he said. The 600 acres of Whiskeytown that Garcia had treated on a rotating schedule easily survived the Carr Fire. Clearly visible lines ran up the ridges, like a photograph divided into black-and-white and full-color panels. On one side stood tree skeletons charred by the blaze. On the other, healthy groves of green trees.

But despite such proven effectiveness, fuels reduction has never attained mainstream acceptance or funding in Sacramento, the state capital, or in Washington, D.C. Half of Garcia’s annual $1 million fire management budget pays for a crew of firefighters and a garage full of equipment to respond to and put out fires. The other half is devoted to clearing brush and small trees.

Garcia said it would cost about $3.5 million to treat 5,000 to 6,000 acres annually. A seven-year rotation would treat the entire park, he said. The risk of fires bounding out of Whiskeytown would be substantially reduced, Garcia said, because they would be much easier to control.

In Garcia’s mind, the price paid for starving his budget was enormous: The Carr Fire incurred $120 million in federal disaster relief, $788 million in property insurance claims, $130 million in cleanup costs, $50 million in timber industry damage, $31 million in highway repair and erosion control costs, $2 million annually in lost property tax revenue and millions more in lost business revenue.

“For $3.5 million a year, you could buy a lot more opportunity to prevent a lot of heartache and a lot of destruction,” Garcia said. “You’d make inroads, that’s for sure. Prevention is absolutely where our program needs to go. It’s where California needs to go.”

Stoked by the land Garcia had been unable to clear, the Carr Fire raged, despite the grueling work of almost 1,400 firefighters, supported by 100 fire engines, 10 helicopters, 22 bulldozers and six air tankers. The firefighters were trying to set a perimeter around the angry fire, which was heading north. In two days it burned over 6,000 acres and incinerated homes in French Gulch, a Gold Rush mining town set between two steep ridges.

Late on July 25, the fire changed course. The hot Central Valley began sucking cold air from the Pacific Coast. By evening, strong gusts were pushing the fire east toward Redding at astonishing speed. By midnight, the Carr Fire, now 60 hours old, had charged across 10 miles and 20,000 acres of largely unsettled ground.

The fire raced across southwest Shasta County. By early evening on July 26, it burned through 20,000 more acres of brush and trees and reached the Sacramento River, which flows through Redding. From a rise at the edge of his Land Park subdivision, Charley Fitch saw flames 30 feet tall. A diabolical rain of red embers was pelting the brush below him, sparking new fires. He jumped into his vehicle, drove back to the house and alerted his wife, Susan, it was time to leave.

“Do You Like the Brush or Do You Want Your Home to Burn?”

On the outskirts of Redding, the Carr Fire encountered even more prodigious quantities of fuel: the homes and plastic furniture, fences, shrub and trees of exurban Shasta County.

Two hours past midnight on July 26, Jeff Coon was startled awake by his dogs. Through the curtain he saw the flashing blue lights of a passing county sheriff cruiser. He heard evacuation orders sternly issued over bullhorns. Coon, a retired investment adviser, smelled smoke. The sky east of his home on Walker Terrace, in the brush and woodlands 5 miles west of Redding, was red with wildfire.

Almost every other wildfire Coon experienced in Redding started far from the city and headed away from town. The Carr Fire was behaving in surprising ways. It was bearing down on Walker Terrace, which is where the ring of thickly settled development in the brush and woods outside Redding begins. Coon’s Spanish tile ranch home at the end of the street would be the first to encounter the flames.

“I jumped into my truck and caught up with the sheriff down the road,” Coon recalled. He said: ‘Evacuate immediately! Like now!’ My wife and I didn’t pack much. She grabbed the dogs and some food. I grabbed some shirts.”

In the terrible and deadly attack over the next 20 hours, the Carr Fire killed six people — four residents and two firefighters — and turned nearly 1,100 houses into smoking rubble, including all but two of the more than 100 homes in Keswick, a 19th-century mining-era town outside Redding. Two more first responders died after the fire burned through Redding.

The horrific consequences were entirely anticipated by city and county authorities. Both local governments prepared comprehensive emergency planning reports that identified wildfire as the highest public safety threat in their jurisdictions. Redding sits at the eastern edge of thousands of acres of brushy woodlands, known as the wildland urban interface, now thick with homes built over the past two decades and classified by the state and county as a “very high fire hazard severity zone.” Nearly 40 percent of the city is a very high hazard severity zone.

To reduce the threat, the county plan calls for a “commitment of resources” to initiate “an aggressive hazardous fuels management program,” and “property standards that provide defensible space.” In effect, keeping residents safe demands that residents and authorities starve fires.

The Redding emergency plan noted that from 1999 to 2015, nine big fires had burned in the forests surrounding Redding and 150 small vegetation fires ignited annually in the city. The city plan called for measures nearly identical to the county’s to reduce fuel loads. And it predicted what would happen if those measures weren’t taken. “The City of Redding recently ran a fire scenario on the west side, which was derived from an actual fire occurrence in the area,” wrote the report’s authors. “As a result of the fire-scenario information, it was discovered that 17 percent of all structures in the city could be affected by this fire.”

The planning reports were mostly greeted by a big civic yawn. City and county building departments are enforcing state regulations that require contractors to “harden” homes in new subdivisions with fireproof roofs, fire-resistant siding, sprinkler systems and fire-resistant windows and eaves. But the other safety recommendations achieved scant attention. The reason is not bureaucratic mismanagement. It’s civic indifference to fire risk. In interview after interview, Redding residents expressed an astonishing tolerance to the threat of wildfires.

Despite numerous fires that regularly ignite outside the city, including one that touched Redding’s boundary in 1999, residents never expected a catastrophe like the Carr Fire. In public opinion polls and election results, county and city residents expressed a clear consensus that other issues — crime, rising housing prices, homelessness and vagrancy — were much higher priorities.

Given such attitudes, fire authorities in and outside the city treated the fire prevention rules for private homeowners as voluntary. State regulations require homeowners in the fire hazard zones to establish “defensible spaces.” The rules call for homeowners to reduce fuels within 100 feet of their houses or face fines of up to $500. Cal Fire managers say they conduct 5,000 defensible space inspections annually in Shasta County and neighboring Trinity County. Craig Wittner, Redding’s fire marshal, said he and his team also conduct regular inspections.

State records show not a single citation for violators was issued in Shasta County in 2017 or this year.

Wittner explained how public indifference works in his city. Each year his budget for brush clearing amounts to about $15,000. Yet even with his small program, residents complain when crews cut small trees and brush. “They like living close to nature,” he said. “They like the privacy. I put it to them this way: Do you like the brush or do you want your home to burn down?”

Redding owns and manages more than 2,000 acres of public open space, about a quarter of the heavily vegetated land within city boundaries. The city’s program to clear brush from public lands averages 50 acres annually. Brush and clearing on private land is virtually nonexistent. Whether or not that changes could hinge on a lawsuit filed in mid-September and a new property tax program being prepared by city officials.

Jaxon Baker, the developer of Land Park and Stanford Hills, two major residential complexes, filed the suit. In it he argued that the city anticipated the deadly consequences of a big fire in west Redding, but did not adequately follow its own directives to clear brush from city-owned open spaces. Redding’s Open Space Master Plan, completed in August, sets out goals for future land and recreational investments. It does not mention fire as a potential threat. Baker’s suit called for rescinding that plan and writing a new one that identifies fire as a higher priority in municipal open space management. “It makes sense,” Baker said. “We have a lot of city-owned land that burns. We just learned that.”

On Nov. 6, the Redding City Council acknowledged that Baker was right and rescinded the Open Space Master Plan, thereby resolving the lawsuit. Preparations for writing a new one have not yet been addressed by the council. Barry Tippin, Redding’s city manager, said that city officials are preparing a proposal to establish a citywide defensible space district and a new property tax to sharply increase public spending for fuels reduction on public and private land. “This is a city that is leery of new taxes,” Tippin said. “But after what happened here in the summer, people may be ready for this kind of program.”

Coon, who had evacuated his neighborhood as fire engulfed it, returned to find his home standing. He wasn’t surprised. Prevention, he said, works, and he invested in it, even without any local requirements that he do so.

Though his home was built in 1973 and remodeled in 1993, it met almost all of the requirements of Shasta County’s latest fire safe building codes. The mansard roof was fire resistant, as were the brick walls. Coon paid attention, too, to the eaves, which he kept protected from blowing leaves. And he didn’t have a wooden fence.

Prompted by his son, a firefighter with Cal Fire, and his own understanding of fire risk, Coon had also established a big perimeter of light vegetation around his house, a safe zone of defensible space. He worked with the Bureau of Land Management to gain a permit to clear a 100-foot zone of thick brush and small trees from the federal land that surrounded his house. He trimmed his shrubs, kept the yard clear of leaves and branches, cleaned out the gutters and discarded plastic items that could serve as fuel. On days designated for burning, he incinerated debris piles.

The project took two summers to complete. When he was finished, his home stood amid a big open space of closely cut grass, rock and small shrubs. In effect, Coon had set his home in a savanna, a fire-safe setting that looked much different from the shaded, grassy, shrub and leafy yards of neighbors who clearly liked mimicking the federal woodlands that surrounded them.

When Coon returned to Walker Terrace days after the fire passed through Redding, his yard was covered in ash and charred tree limbs. But his house remained. So did the garage where he kept his prized 1968 Camaro.

“How Do You Want Your Smoke?”

A warming planet, conflicting government aims, human indifference or indolence — all are serious impediments to controlling the threat of wildfires in California. But they are not the only ones.

Add worries about air pollution and carbon emissions.

The California air quality law, enforced by county districts, requires fire managers interested in conducting controlled burns as a way of managing fire risk to submit their plans for review in order to gain the required permits. County air quality boards also set out specific temperature, moisture, wind, land, barometric, personnel and emergency response conditions for lighting prescribed fires.

The limits are so specific that Tom Garcia in the Whiskeytown National Recreation Area said only about six to 10 days a year are suitable for managed burns in Shasta County.

John Waldrop, the manager of the Shasta County Air Quality District, said he’s sympathetic to Garcia’s frustration but determined to meet his obligations to protect the public’s health. Waldrop said that federal and state agencies and private timber operators lit prescribed burns on an average of 3,600 acres annually in Shasta County over the last decade. Most burns are less than 100 acres, which fits his agency’s goal of keeping the air clean and fine particulate levels below 35 micrograms per cubic meter, the limit that safeguards public health.

Waldrop said it would take 50,000 acres of prescribed fire annually to clear sufficient amounts of brush from the county’s timberlands to reduce the threat of big wildfires. That means approving burns that span thousands of acres and pour thousands of tons of smoke into the air.

“From an air quality standpoint, that is a harder pill for us to swallow,” Waldrop said.

Balancing the threat of wildfires against the risk of more smoke is a choice that Shasta residents may be more prepared to make. During and after the Carr Fire, Redding residents breathed air for almost a month with particulate concentrations over 150 micrograms per cubic meter. That is comparable to the air in Beijing.

“We’re at a point where society has to decide,” Waldrop said, “how do you want your smoke? Do you want it at 150 micrograms per cubic meter from big fires all summer long, or a little bit every now and again from prescribed burning?”

Another air pollution challenge Californians face is the troubling connection between wildfires and carbon emissions. Two years ago, California passed legislation to reduce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to 258.6 million metric tons annually by 2030. That is a 40 percent reduction from levels today of about 429 million metric tons a year.

Reaching that goal, a stretch already, will be far more difficult because of runaway wildfires. Last year, wildfires poured 37 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into California’s atmosphere, according to a state report made public this year. Even higher totals are anticipated for 2018.

Efforts to quell the fires with more prescribed burns will add, at least for a number of years, more carbon dioxide. Prescribed fires produce an average of 6 tons of carbon per acre, according to scientific studies. Burning half a million acres annually would produce 3 million more metric tons of greenhouse gases.

A Matter of Priorities and Focus

For now, California can seem locked in a vicious and unwinnable cycle: Surprised anew every year by the number and severity of its wildfires, the state winds up pouring escalating amounts of money into fighting them. It’s all for a good, if exhausting, cause: saving lives and property.

But such effort and expenditure drains the state’s ability to do what almost everyone agrees is required for its long-term survival: investing way more money in prevention policies and tactics.

“It’s the law of diminishing returns,” Garcia said. “The more money we put into suppression is not buying a lot more safety. We are putting our money in the wrong place. There has to be a better investment strategy.”

Just as drying Southwest conditions forced Las Vegas homeowners to switch from green lawns to desert landscaping to conserve water, fire specialists insist that Californians must quickly embrace a different landscaping aesthetic to respond to the state’s fire emergency. Defensible spaces need to become the norm for the millions of residents who live in the 40 percent of California classified as a high fire-threat zone.

Residents need to reacquaint themselves with how wicked a wildfire can be. Counties need to much more vigorously enforce defensive space regulations. Sierra foothill towns need to establish belts of heavily thinned woodland and forest 1,000 feet wide or more, where big fires can be knocked down and extinguished. Property values that now are predicated on proximity to sylvan settings need to be reset by how safe they are from wildfire as they are in San Diego and a select group of other cities.

“We solved this problem in the urban environment,” said Timothy Ingalsbee, executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology, a national wildfire research and policy group in Oregon. “Towns were all once made of wood. The Great Chicago Fire. The San Francisco fire. We figured out they can’t make cities out of flammable materials. They hardened them with brick and mortar and building codes and ordinances for maintaining properties.

“This is a really solvable problem with the technology we have today. Making homes and communities that don’t burn up is very solvable. It’s a matter of priorities and focus.”

In a select group of towns in and outside California, residents have gotten that message. Boulder, Colorado, invested in an expansive ring of open space that surrounds the city. It doubles as a popular recreation area and as a fuel break for runaway fires that head to the city.

San Diego is another example. After big and deadly fires burned in San Diego in 2003 and 2007, residents, local authorities and San Diego Electric and Gas sharply raised their fire prevention efforts. Thirty-eight volunteer community fire prevention councils were formed and now educate residents, provide yard-clearing services and hold regular drives to clear brush and trees. SDE&G has spent $1 billion over the last decade to bury 10,000 miles of transmission lines, replace wooden poles with steel poles, clear brush along its transmission corridors and establish a systemwide digital network of 177 weather stations and 15 cameras.

The system pinpoints weather and moisture conditions that lead to fire outbreaks. Firefighting agencies have been considerably quicker to respond to ignitions than a decade ago. SDE&G also operates an Erickson air tanker helicopter to assist fire agencies in quickly extinguishing blazes.

The area’s experience with wildfire improved significantly.

“We haven’t gone through anything like what we had here in 2003 and 2007,” said Sheryl Landrum, the vice president of the Fire Safe Council of San Diego County, a nonprofit fire prevention and public education group. “We’ve had to work hard here to educate people and to convince people to be proactive and clear defensible spaces. People are aware of what they need to do. Our firefighting capabilities are much more coordinated and much stronger.”

_____________________

Keith Schneider, a former national correspondent and a contributor to the New York Times, is the senior editor and producer at Circle of Blue, which covers the global freshwater crisis from its newsroom in Traverse City, Michigan. This article was originally published by ProPublica.

California Knew the Carr Wildfire Could Happen. It Failed to Prevent it. by Keith Schneider is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 International License.

Capturing Carbon to Fight Climate Change is Dividing Environmentalists

By Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Holly Jean Buck

#science #environment #climatechange #global #nature #technology

Environmental activists are teaming up with fresh faces in Congress to advocate for a Green New Deal, a bundle of policies that would fight climate change while creating new jobs and reducing inequality. Not all of the activists agree on what those policies ought to be.

Some 626 environmental groups, including Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity and 350, recently laid out their vision in a letter they sent to U.S. lawmakers. They warned that they “vigorously oppose” several strategies, including the use of carbon capture and storage – a process that can trap excess carbon pollution that’s already warming the Earth, and lock it away.

In our view, as a political philosopher who studies global justice and an environmental social scientist, this blanket opposition is an unfortunate mistake. Based on the need to remove carbon from the atmosphere, and the risks in relying on land sinks like forests and soils alone to take up the excess carbon, we believe that carbon capture and storage could be a powerful tool for making the climate safer and even rectifying historical climate injustices.

Global inequality

We think the U.S. and other rich countries should accelerate negative emissions research for two reasons.

First, they can afford it. Second, they have a historical responsibility as they burned a disproportionate amount of the carbon causing climate change today. Global warming is poised to hit the least-developed countries, including dozens that were colonized by these wealthier nations, the hardest.

Consider this: The entire African continent emits less carbon than the U.S., Russia or Japan.

Yet Africa is likely to experience climate change impacts sooner and more intensely than any other region. Some African regions are already experiencing warming increases at more than twice the global rate. Coastal and island nations like Bangladesh, Madagascar and the Marshall Islands face near or total destruction.

But the world’s richest nations have been slow to endorse and support the necessary research, development and governance for negative emissions technologies.

Bad track record with coal

What explains the objections from climate justice advocates?

The U.S. has heavily funded experiments with carbon capture and storage to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from new coal-fired power plants since George W. Bush’s presidency.

Those efforts have not paid off, partly because of economics. Natural gas and renewable energy have become cheaper and more popular than coal for generating electricity.

Only a handful of coal-fired power plants are under construction in the U.S., where closures are routine. The industry is in trouble everywhere, with few exceptions.

In addition, carbon capture with coal has a bad track record. The biggest U.S. experiment is the US$7.5 billion Kemper power plant in Mississippi. It ended in failure in 2017 when state power authorities ordered the plant operator to give up on this technology and rely on natural gas instead.

Other uses

Carbon capture and storage, however, isn’t just for fossil-fuel-burning power plants. It can work with industrial carbon dioxide sources, such as steel, cement and chemical plants and incinerators.

Then, one of two things can happen. The carbon can be turned into new products, such as fuels, cement, soft drinks or even shoes.

Carbon can also be stored permanently if it is injected underground, where geologists believe it can stay put for centuries.

Until now, a common use for captured carbon is extracting oil out of old wells. Burning that petroleum, however, can make climate change worse.

Captured carbon has a variety of industrial uses, including oil extraction and fire extinguisher manufacturing. U.S. Energy Department’s National Energy Technology Laboratory, Public Domain.

Going carbon negative

This technology may potentially also remove more carbon than gets emitted – as long as it’s designed right.

One example is what’s called bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, where farm residues or crops like trees or grasses are grown to be burned to generate electricity. Carbon is separated out and stored at the power plants where this happens.

If the supply chain is sustainable, with cultivation, harvesting and transport done in low-carbon or carbon-neutral ways, this process can produce what scientists call negative emissions, with more carbon removed than released. Another possibility involves directly capturing carbon from the air.

Scientists point out that bioenergy with carbon capture and storage could require vast amounts of land for growing biofuels to burn. And climate advocates are concerned that both approaches could pave the way for oil, gas and coal companies and big industries to simply continue with business as usual instead of phasing out fossil fuels.

Many experts agree that limiting global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius will require reducing the volume of carbon emissions through energy efficiency and renewable-energy generation and CO₂ removal. MCC, CC BY-SA

Natural solutions

Every pathway to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius in the most recent U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report projected the use of carbon removal approaches.

Planting more trees, composting and farming in ways that store carbon in soils and protecting wetlands can also reduce atmospheric carbon. We believe the natural solutions many environmentalists might prefer are crucial. But soaking up excess carbon through afforestation on a massive scale could encroach on farmland.

To be sure, not all environmentalists are writing off carbon capture and storage.

The Sierra Club, Environmental Defense Fund and Natural Resources Defense Council, along with many other big green organizations, did not sign the letter, which objected not just to carbon capture and storage but also to nuclear power, emissions trading and converting trash into energy through incineration.

Rather than leave carbon removal technologies out of the Green New Deal, we suggest that more environmentalists consider their potential for removing carbon that has already been emitted. We believe these approaches could potentially create jobs, foster economic development and reduce inequality on a global scale – as long as they are meaningfully accountable to people in the world’s poorest nations.

____________________

Olúfẹmi Táíwò completed his Ph.D. at the University of California, Los Angeles, and teaches philosophy at Georgetown University. Holly Jean Buck is a NatureNet Science Fellow at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and author of After Geoengineering, a look at best and worst-case futures under climate engineering.

Capturing Carbon to Fight Climate Change Is Dividing Environmentalists by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Holly Jean Buck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Cold, Hard Harvest: Making the Case for Frozen Produce

by Nicco Pandolfi

#argument, #proposal, #valuesbased, #descriptive, #systemanalysis, #advice, #pathos, #ethos, #logos, #kairos, #food

I recently acquired a hand-me-down chest freezer from a colleague, and have since been daydreaming about all the ways it is going to enhance my food life. From preserving berries and greens at peak freshness to caching away soups and stocks, the extra freezer space will help me spend my food dollars more strategically. With a little forethought, it provides an alternative to relying on distantly sourced, subpar produce in the bleak winter months. Frozen foods have long been marginalized by foodies as pale, second-rate substitutes for their fresh equivalents, but those sentiments are starting to shift. Here are a few pitches for ushering in a new age of appreciation for these undersung foot soldiers of the local food movement.

The Climate Change Pitch

The lab-coated grand jury has spoken: Homo sapiens is a measurable contributor to climate change (United Nations IPCC, 2018). To most this is not news, but it does prompt us to ask how we can take action to mitigate rather than augment our role in driving carbon emissions. Since food production, consumption and disposal are among the primary ways we interact with the planet, our diet seems like a logical place to begin. Eating food in the 21st century is a wildly intricate process that involves far more steps than we can even comfortably wrap our minds around. As such, any quest to shrink our carbon stomach-print must begin by simplifying our relationship with food.

Like any process, food sourcing can be simplified either by eliminating steps or by reducing them to a more observable scale. By establishing a vibrant regional food economy, we can accomplish both of these aims. Unfortunately the farther from the equator a community is, the fewer days per year it experiences that are suitable for food production without implementing massively energy-intensive workarounds like heated greenhouses. Simply put, it costs energy to work against the seasons. Embracing frozen produce as a piece of the locavore pie allows us to grow while the sun shines and freeze the resulting bounty to get us through the less productive winter months.

The norm, of course, is to import fresh produce from wherever it is most cheaply grown, which involves considerable carbon emissions. Frozen storage has carbon costs of its own but industrial freezers are gaining in efficiency, and unlike freight transit vehicles they can be easily converted to run on renewable energy. Moreover, a recent study in the U.K. discovered that the carbon footprint of a typical family meal was 5% smaller when made with frozen ingredients as opposed to fresh ones. Consider that for plant-based foods on the national market, transportation accounts for over 16% of total emissions and suddenly you are talking about substantial carbon savings when you choose local frozen produce as an alternative.

The Food Waste Pitch

A 2011 study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization examining food waste in several industrialized countries found that 40% of all food is wasted along its journey from producer to consumer. For fruits and vegetables that figure is closer to 52%. What’s more, close to half of that waste occurs before it even reaches the distributor, let alone the end-consumer. These are wild numbers when you consider what is lost: not widgets or knick knacks, but the stuff that sustains human life and health.

The first logical front to attack this waste problem on is pre-season crop planning. When there are established outlets for small-batch (i.e. 1,000 lb rather than 10,000 lb) freezing, producers can look at historical data and estimate a certain percentage of projected yield that – either because of quality or short shelf life – will not sell on the fresh market. Growers can then make arrangements with regional processors for this portion of the crop to be frozen, locking in a fair price ahead of time without the urgent pressure to move perishable inventory mid-season. In this way, farmers can turn potential waste into nutritious and saleable food.

Of course, January’s fireside predictions are not always borne out in the field come July. The occasional bumper crop or crop failure is a given, so it is important to develop ways to both preserve unusually large harvests and ensure a steady supply of frozen products when yields are lower than expected. A collaborative sourcing model that spreads these risks out over several growers can help ensure that no one is hung out to dry, while also capturing literal tons of good food before it becomes waste.

The “Slow Money” Pitch

Our economic system is not set up to make capital readily available to small farms and food businesses, which are often perceived as risky ventures. If we wish to safeguard sources of healthy food and ensure conscientious land stewardship, we need to create a framework for directing resources to the next generation of farmers and food innovators. There is a well-documented multiplier effect that kicks in when dollars are spent at small independent businesses rather than national or transnational chains, with the net result that two to three times more of this “slow money” stays in local circulation.

Enfranchising frozen foods as bona fide culinary players in the regional foodshed expands opportunities for small and mid-size growers, offering them outlets for far more food than they can sell fresh. Tapping into the frozen market can create new revenue streams, allowing producers to re-invest in farm infrastructure that will help them capture more of the existing harvest and even grow their production to meet new demand. Moreover, as chefs give frozen foods a second chance, they rely less on the Just-In-Time inventory model touted by broadline distributors and can begin to redesign their kitchen spaces to accommodate more frozen storage.

If you are willing to work with frozen produce, all it takes is a little planning and collaboration with growers and food hubs to secure year-round local sources of many kitchen staples. As these collaborations mature, they form an increasingly resilient food web that shifts the culture of cooking in both professional and home kitchens. In this model, any fruit or vegetable that can be grown in a given region represents an opportunity to recapture food dollars and watch the multiplier effect ripple through the local economy.

The Regional Food Security Pitch

Most dollars we spend immediately subdivide into pennies that scatter all over the world. Sheer geography blinds us to the real human, environmental and social consequences of our economic choices. Nowhere is this truer than in the food world. Only by sourcing from local producers can we witness the impacts of our food choices and vote with our dollars for best practices that create a foundation for lasting regional food security. By food security I mean not simply access to calories, but community-wide access to healthy, real food from trusted producers who belong to the same community as the eaters they are feeding.

There is an emerging scientific consensus that extreme weather events are on the rise, and such events can impact regional infrastructure for transporting food goods. Major flooding, winter storms and other natural disasters can create serious obstacles for both shipping out and bringing in food. Despite the temporary nature of these phenomena and the damage they cause, a pinch in the food supply has immediate effects on a community. More importantly, access to good food should be a basic right and its absence is linked to other types of disenfranchisement, as the plight of many food deserts shows. Freezing and storing the local harvest is one way to establish reserves of good food in the interest of community resilience and improving food access for all.

In the long run, food security is best preserved by fostering a culture that values food from soil to belly. This hinges on treating cuisine as a cultural asset to be protected and built upon as we pass it from generation to generation. A key piece of this cultural inheritance is the understanding that each food has its time, and is best enjoyed during that brief glorious window. The next option we should look to is preserving it as that window closes, while it is still fresh. Though some will call me a blasphemer for saying it, one can only eat so many pickles. We need to think of frozen produce not as a consolation prize, but a snapshot of summer that we can unearth to warm us on the coldest day of the year.

The Quality Pitch

To be sure, none of these pitches will sway anyone who thinks they are just window dressing designed to make them forget the reason they spurned frozen foods in the first place: a nagging sense that they are weak stand-ins for their fresh counterparts. Fortunately, there is growing evidence to the contrary, as frozen foods are gaining credence and approval in the realms of both flavor and nutrition.

Despite their long-standing stigma, frozen foods are shedding their bad reputation as eaters and chefs make increasingly complex decisions about where they get their food. In a 2014 survey of food industry professionals, 75% of respondents believed there are unnecessary negative connotations attached to frozen food, a staggering 60% increase from an earlier version of the survey conducted just three years prior. Such a precipitous shift in industry opinion indicates that this is more than just a fringe idea.

According to several recent studies frozen fruits and vegetables have equal or greater nutritional value than their fresh cousins. This is in large part because fresh produce has been shown to decline in nutrients the longer it sits between harvesting and eating, whereas frozen produce stops its nutritive shot clock the moment its temperature drops. Hence the popularity of the term “fresh frozen,” which conveys a useful message despite its ubiquitousness as fodder for claim-tastical food marketing campaigns.

Bringing it back home

If any of these pitches resonate with you, we are fortunate to have some great options for frozen local produce in northwest Michigan. One is Goodwill Industries’ Farm to Freezer project, a job training program that teaches kitchen skills by freezing small batches of local produce. They carry a wide range of fruits and vegetables, which are available at many area grocers. Oryana Natural Foods Co-Op recently partnered with Farm to Freezer and Cherry Capital Foods to pack and distribute a line of Fair Harvest berries, starting with organic strawberries grown at Ware Farm in Benzie County. Some area CSAs, such as Providence Farm in Central Lake, even offer frozen Michigan fruit as an optional add-on to members’ shares. As we weather the harsh realities of a Michigan winter, here’s to taking some time to honor the freezer and carve out a more respectable place for it in our foodshed.

Works Cited

United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5? (United Nations, 2018), available from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

____________________

Nicco Pandolfi works as a librarian at Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City, MI. His poetry and prose have appeared in Dunes Review, Pulp, and Edible Grand Traverse. He mostly writes about what he mostly thinks about: music and food.

Cold, Hard Harvest: Making the Case for Frozen Produce by Nicco Pandolfi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This work was first published in Edible Grand Traverse magazine.

The Defense Department Is Worried about Climate Change – and Also a Huge Carbon Emitter

by Neta C. Crawford

Scientists and security analysts have warned for more than a decade that global warming is a potential national security concern.

They project that the consequences of global warming – rising seas, powerful storms, famine and diminished access to fresh water – may make regions of the world politically unstable and prompt mass migration and refugee crises.

Some worry that wars may follow.

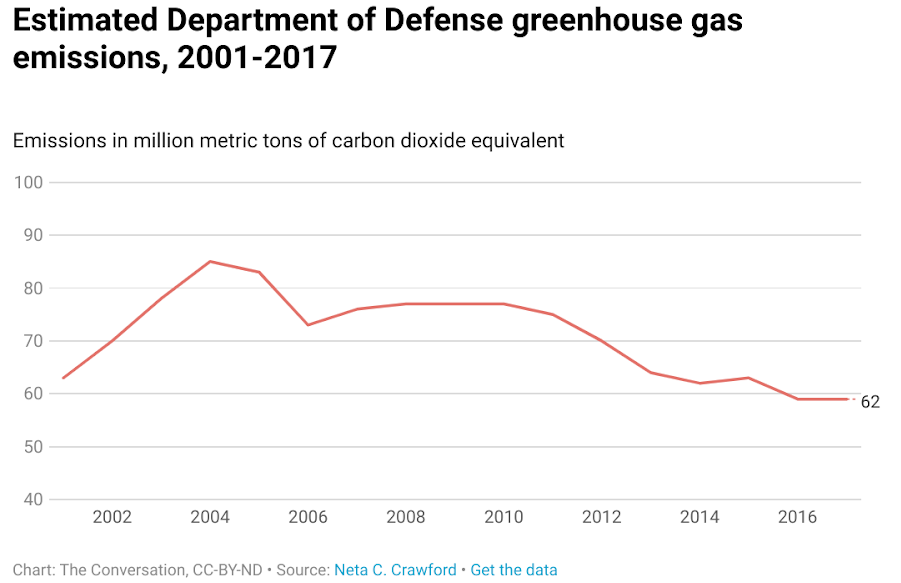

Yet with few exceptions, the U.S. military’s significant contribution to climate change has received little attention. Although the Defense Department has significantly reduced its fossil fuel consumption since the early 2000s, it remains the world’s single largest consumer of oil – and as a result, one of the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters.

A broad carbon footprint

I have studied war and peace for four decades. But I only focused on the scale of U.S. military greenhouse gas emissions when I began co-teaching a course on climate change and focused on the Pentagon’s response to global warming. Yet, the Department of Defense is the U.S. government’s largest fossil fuel consumer, accounting for between 77% and 80% of all federal government energy consumption since 2001.

In a newly released study published by Brown University’s Costs of War Project, I calculated U.S. military greenhouse gas emissions in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent from 1975 through 2017.

Today China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, followed by the United States. In 2017 the Pentagon’s greenhouse gas emissions totaled over 59 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. If it were a country, it would have been the world’s 55th largest greenhouse gas emitter, with emissions larger than Portugal, Sweden or Denmark.

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

The largest sources of military greenhouse gas emissions are buildings and fuel. The Defense Department maintains over 560,000 buildings at approximately 500 domestic and overseas military installations, which account for about 40% of its greenhouse gas emissions.

The rest comes from operations. In fiscal year 2016, for instance, the Defense Department consumed about 86 million barrels of fuel for operational purposes.

Why do the armed forces use so much fuel?

Military weapons and equipment use so much fuel that the relevant measure for defense planners is frequently gallons per mile.

Aircraft are particularly thirsty. For example, the B-2 stealth bomber, which holds more than 25,600 gallons of jet fuel, burns 4.28 gallons per mile and emits more than 250 metric tons of greenhouse gas over a 6,000 nautical mile range. The KC-135R aerial refueling tanker consumes about 4.9 gallons per mile.

A single mission consumes enormous quantities of fuel. In January 2017, two B-2B bombers and 15 aerial refueling tankers traveled more than 12,000 miles from Whiteman Air Force Base to bomb ISIS targets in Libya, killing about 80 suspected ISIS militants. Not counting the tankers’ emissions, the B-2s emitted about 1,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases.

Quantifying military emissions

Calculating the Defense Department’s greenhouse gas emissions isn’t easy. The Defense Logistics Agency tracks fuel purchases, but the Pentagon does not consistently report DOD fossil fuel consumption to Congress in its annual budget requests.

The Department of Energy publishes data on DOD energy production and fuel consumption, including for vehicles and equipment. Using fuel consumption data, I estimate that from 2001 through 2017, the DOD, including all service branches, emitted 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases. That is the rough equivalent of driving of 255 million passenger vehicles over a year.

Of that total, I estimated that war-related emissions between 2001 and 2017, including “overseas contingency operations” in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Syria, generated over 400 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent — roughly equivalent to the greenhouse emissions of almost 85 million cars in one year.

Real and present dangers?

The Pentagon’s core mission is to prepare for potential attacks by human adversaries. Analysts argue about the likelihood of war and the level of military preparation necessary to prevent it, but in my view, none of the United States’ adversaries – Russia, Iran, China and North Korea – are certain to attack the United States.

Nor is a large standing military the only way to reduce the threats these adversaries pose. Arms control and diplomacy can often de-escalate tensions and reduce threats. Economic sanctions can diminish the capacity of states and nonstate actors to threaten the security interests of the U.S. and its allies.

In contrast, climate change is not a potential risk. It has begun, with real consequences to the United States. Failing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will make the nightmare scenarios strategists warn against – perhaps even “climate wars” – more likely.

A case for decarbonizing the military

Over the past last decade the Defense Department has reduced its fossil fuel consumption through actions that include using renewable energy, weatherizing buildings and reducing aircraft idling time on runways.

The DOD’s total annual emissions declined from a peak of 85 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2004 to 59 million metric tons in 2017. The goal, as then-General James Mattis put it, is to be “unleashed from the tether of fuel” by decreasing military dependence on oil and oil convoys that are vulnerable to attack in war zones.

Since 1979, the United States has placed a high priority on protecting access to the Persian Gulf. About one-fourth of military operational fuel use is for the U.S. Central Command, which covers the Persian Gulf region.

As national security scholars have argued, with dramatic growth in renewable energy and diminishing U.S. dependence on foreign oil, it is possible for Congress and the president to rethink our nation’s military missions and reduce the amount of energy the armed forces use to protect access to Middle East oil.

I agree with the military and national security experts who contend that climate change should be front and center in U.S. national security debates. Cutting Pentagon greenhouse gas emissions will help save lives in the United States, and could diminish the risk of climate conflict.

____________________

Neta C. Crawford is a professor of Political Science at Boston University and the author of Accountability for Killing: Moral Responsibility for Collateral Damage in America’s Post-9/11 Wars (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, Humanitarian Intervention (Cambridge University Press, 2002.)

The Defense Department Is Worried about Climate Change – and Also a Huge Carbon Emitter by Neta C. Crawford is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The Dirt on Soil Loss from the Midwest Floods

by Jim Ippolito and Mahdi Al-Kaisi

#science #environment #climatechange #nature #rural

“Farmland being flooded by Missouri and Red Rivers in North Dakota” by Good Free Photos is in the Public Domain, CC0

As devastating images of the 2019 Midwest floods fade from view, an insidious and longer-term problem is emerging across its vast plains: The loss of topsoil that much of the nation’s food supply relies on.

Today, Midwest farmers are facing millions of bushels of damaged crops such as soybean and corn. This spring’s heavy rains have already caused record flooding, which could continue into May and June, and some government officials have said it could take farmers years to recover.

Long after the rains stop, floodwaters continue to impact soil’s physical, chemical and biological properties that all plants rely on for proper growth. Just as very wet soils would prevent a homeowner from tending his or her garden, large amounts of rainfall prevent farmers from entering a wet field with machinery. Flooding can also drain nutrients out of the soil that are necessary for plant growth as well as reduce oxygen needed for plant roots to breathe, and gather water and nutrients.

As scientists who have a combined 80 years of experience studying soil processes, we see clearly that many long-term problems farmers face from floodwaters are steeped in the soil. This leads us to conclude that farmers may need to take far more active measures to manage soil health in the future as weather changes occur more drastically due to climate change and other factors.

Here are some of the perils with flooded farmland that can affect the nation’s food supply.

Suffocating soil

When soil is saturated by excessive flooding, soil pores are completely filled with water and have little to no oxygen present. Much like humans, plants need oxygen to survive, with the gas taken into plants via leaves and roots. Also identical to humans, plants – such as farm crops – can’t breathe underwater.

Essentially, excess and prolonged flooding kills plant roots because they can’t breathe. Dead plant roots in turn lead to death of aboveground plant, or crop, growth.

Another impact of flooding is compacted soil. This often occurs when heavy machinery is run over wet or saturated farmland. When soils become compacted, future root growth and oxygen supply are limited. Thus, severe flooding can delay or even prevent planting for the entire growing season, causing significant financial loss to farmers.

Loss of soil nutrients

When flooding events occur, such as overwatering your garden or as with the 2019 Midwest flooding, excess water can flush nutrients out of the soil. This happens by water running offsite, leaching into and draining through the ground, or even through the conversion of nutrients from a form that plants can utilize to a gaseous form that is lost from the soil to the atmosphere.

Regardless of whether you are a backyard gardener or large-scale farmer, these conditions can lead to delays in crop planting, reduced crop yields, lower nutritive value in crops and increased costs in terms of extra fertilizers used. There is also the increased stress within the farming community – or for you, the backyard gardener who couldn’t plant over the weekend due to excess rainfall. This ultimately increases the risk of not producing ample food over time.

Small microbial changes have big effects

Flooding on grand scales causes soils to become water-saturated for longer than normal periods of time. This, in turn, affects soil microorganisms that are beneficial for nutrient cycling.

Flooded soils may encounter problems caused by the loss of a specific soil microorganism, arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi. These fungi colonize root systems in about 90% to 95% of all plants on Earth in a mutually beneficial relationship.

The fungi receive energy in the form of carbon from the plant. As the fungi extend thread-like tendrils into the soil to scavenge for nutrients, they create a zone where nutrients can be taken up more easily by the plant. This, in turn, benefits nutrient uptake and nutritive value of crops.

When microbial activity is interrupted, nutrients don’t ebb and flow within soils in the way that is needed for proper crop growth. Crops grown in previously flooded fields may be affected due to the absence of a microbial community that is essential for maintaining proper plant growth.

The current Midwest flooding has far-reaching effects on soil health that may last many years. Recovering from these types of extreme events will likely require active management of soil to counteract the negative long-term effects of flooding. This may include the adoption of conservation systems that include the use of cover crops, no-till or reduced-till systems, and the use of perennials grasses, to name few. These types of systems may allow for better soil drainage and thus lessen flooding severity in soils.

Farmers have the ability to perform these management practices, but only if they can afford to convert over to these new systems; not all farmers are that fortunate. Until improvements in management practices are resolved, future flooding will likely continue to leave large numbers of Midwest fields vulnerable to producing lower crop yields or no crop at all.

____________________

Jim Ippolito is Associate Professor of Environmental Soil Quality/Health at Colorado State University. Mahdi Al-Kaisi is Professor of Soil Management and Environment, Iowa State University. This essay originally appeared in The Conversation.

The dirt on soil loss from the Midwest floods by Jim Ippolito & Mahdi Al-Kaisiis licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Does Recycling Actually Conserve or Preserve Things?

by Samantha MacBride

#scholarly, #argument, #systemanalysis, #logos, #ethos, #kairos, #cognitivebias, #currentevents, #research, #science

“”217” “ by grotos is licensed under CC BY 2.0 (cropped)

There are a series of assumptions behind the familiar assertion that recycling saves resources and energy, and in so doing, protects the environment. These assumptions are in the motto, “recycling saves trees.” With recycling – one assumes – used materials stand in for raw materials. This way, recycled content cuts down on the need to extract (conservation), which in turn prevents some of the environmental damage from extraction that would be taking place without recycling (preservation).

Conservation and preservation are distinct, though linked, ideas. Historians of North American environmentalism distinguish the Conservation Movement, which focused on the responsible management of materials to sustain production and economic growth, from the Preservation Movement, which stressed the protection of wilderness.1 Both movements have been rightly critiqued for failing to consider questions of power and equity in people’s health, dignity, and livelihoods.2 Still, the distinction between conserving resources for use in production, and preserving complex ecosystems (which include people in human settlements), is useful for a question I now pose about recycling. Does recycling, in the way it is practiced today, actually conserve or preserve things that matter?

To answer “yes” requires that a set of assumptions hold true. When we say recycling saves trees, we start by assuming that the paper in the recycling bin goes to a plant to be sorted and baled. Plant managers find buyers for the bales, which are shipped off to a manufacturer. We assume that this manufacturer, individually or as part of a larger industry sector, is weighing the options between using virgin input (wood pulp) or secondary input (recycled paper). When it costs less to use recycled paper as an input, the manufacturer is going to use the secondary material to make things. So far, so good.

But to save trees, much less forests, more has to happen. When the decision is made to use recycled input, the virgin alternative ought to be conserved in a way that preserves ecosystems and people. Preservation isn’t achieved if the virgin stock is directed into a new product that hasn’t existed before; or if it is conserved technically for later use, and then harvested and utilized when economic growth makes for favorable conditions to ramp up production. It’s not enough to simply offer up recycled paper on a commodity market to be grabbed when price signals are favorable. It doesn’t do to merely measure increases in recycled content of various products on the market. Nor is it sufficient to theorize that recycling may have slowed a sectoral growth rate that would have proceeded, all things being equal, faster in an imaginary world in which there was no recycling at all. To save trees in a way that matters ecologically and socially means something more. It means that forests, including forest ecosystems and surrounding livelihoods in all of their complexity, are actually protected in today’s world.

Theoretically, there is no reason why recycling couldn’t deliver on such protection, were it integrated into a system of monitoring that followed through on promises. Such a system would need to identify limits on rates of extraction in accordance with their ecosystemic threat; include long term planning for stabilization of some extractive industries, and phase-out of others; and ensure maximum protection of future lands and ecosystems from development. Under such a system, extractive industries would need to demonstrate to what degree recycled inputs substituted for virgin sources in their sectors annually, and also that their sectors were not encroaching with new development in terrains that matter to people and other living things.

Empirically, there is no question that at certain times, for certain periods, recycling may have conserved virgin resources to some degree; and even that recycling may play a role in localized resource policies, such as boosting timber plantations that spare virgin forests as sources in papermaking. In fact, portions of the assumption of conservation, can be and regularly are dragged out for theoretical and/or empirical testing within the disciplines of resource economics, materials flow analysis, and life cycle analysis. There is much scholarship that asks whether recycling has resulted in, or could theoretically result in, less net extraction or harvest.3 Such inquiries are interesting in their own right, and to the extent that they tell us something about tradeoffs that manufacturers make between virgin and recycled inputs, they inform an understanding of what recycling could, under ideal circumstances, achieve in terms of actual conservation — which would be a precondition for, but not a guarantee of, actual preservation.

We are on shaky ground, however, if we take these assumptions for granted. I trace my concern on this matter to the work of William Stanley Jevons.4 In the 19th century, technological improvements in mining and combustion were greatly improving the efficiency of using coal as fuel. Noting these developments, Jevons argued that, rather than conserve coal, improvements in efficiency, and a subsequent drop in coal price, would paradoxically lead to an increased demand for coal.

The Jevons Paradox. Public Domain.

Now known as Jevons’ Paradox, this perspective observes that when you increase efficiency in production and consumption, you may well see an increase in overall extraction.5 Massive amounts of scholarship have followed the Jevons’ Paradox, most around energy efficiency.6 In the materials realm, recycling can be thought of as a form of efficiency (getting more out of the same input).7 There is a growing body of work tracing the effects of recycling on extraction of virgin materials, in particular in the area of metals.8 Scholars ask questions about conservation of metals in part because the data on their trade is more available than for other materials. It’s more organized. It’s more harmonized among different nations, given the nature of these economies. Both the economy of metals and as well as the material properties of metals make them relatively easy to be recycled over and over again and be reintroduced back into production, especially in comparison the heterogeneous range of synthetic polymers we call plastics. Yet we see growing rates of metals extraction taking place alongside growing recycling rates, worldwide. We can speculate about what those growth rates would have been had recycling not existed, but it would be hard to argue that global production systems are using less virgin raw material as a result of metals recycling, much less that metal recycling is preserving lands from mining.9

“French waste lines” by Charos Pix is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The caveats and careful measurements in the specialized literatures above suggest that recycling can conserve resources temporarily in some cases, almost always absent considerations of preservation. Such nuances fall away, however, as recycling becomes idealized and abstracted as an ethical, “earth-saving” end unto itself. Under-examined assumptions of conservation and preservation run deep through recycling discourse, and are also core to the notion that reuse will cut down on the flow of materials and energy from cradle to grave. Each time reuse and recycling are affirmed in the waste hierarchy, there is a hazy sense that somewhere, by someone, some sort of accounting is going on to ensure that overall, recycling is delivering protection of things that matter. I would wager that many in the media, in environmental education, and even in environmentally focused NGOs hold this position. This is how recycling would, actually and not just in theory, “save the planet.” But is there really any coordinating body who is conducting such accounting? No.10 And is recycling actually preserving ecosystems and livelihoods, or achieving real-world “dematerialization” (the technical term for less use of raw materials overall)? Not in any systematic way.11

Oil, Gas, and Plastics

So far I’ve used the examples of forest products and metals. I have done so because of the historical potency of the motto “recycling saves trees”, and the relatively developed scholarship around steel, aluminum, and other metals. In reality, much more is going on around forestry, or the mining and metals trade, than is taken into account when one simply looks at recycling. But at least we have some data to inform questions. If we examine the plastics industry and the role of plastics recycling, we find that similar assumptions abound, with particular complications, and little information. How can we evaluate the assumption that plastic recycling reduces the need to extract fossil fuels; or the separate but related claim that manufacturing with recycled inputs uses less energy, meaning lower fuel use economy-wide, meaning diminished carbon emissions?

It is well known that only a small percentage of global fossil fuel extraction is used directly in plastics production.12 So even recycling every shred of plastic would not, on its own, diminish the need to drill at current rates by much. Looking specifically at the U.S., the situation is no different. Let’s say we build up domestic plastic recycling capacity in the U.S., as many are calling for in the wake of China’s imports restrictions. What would the effect be of repatriating that tonnage, and feeding it back into domestic production, on domestic fossil fuel extraction – to make plastics, or to generate electricity?

It may surprise you to learn that the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) “is unable to determine the specific amounts or origin of the feedstocks that are actually used to manufacture plastics in the United States.”13

The reason hints at the constantly fluctuating conditions of virgin raw material sourcing that I’ve alluded to above, and data limitations that I’ll elaborate below. The EIA writes:

Because the petrochemical industry has a high degree of flexibility in the feedstock it consumes and because EIA does not collect detailed data on this aspect of industrial consumption, it is not possible for EIA to identify the actual amounts and origin of the materials used as inputs by industry to manufacture plastics. 14

Let’s pivot back to the day-to-day understanding of recycling, in which it is it is axiomatic to assert that plastic recycling saves oil and gas resources.15 On a ton-for-ton basis, in a hypothetical scenario in which recycled materials actually substitute for fossil fuels, and lead to a concomitant net decrease in extraction or fuel combustion, such claims hold. But without data on “actual amounts and origin of materials used as inputs,” it is not possible to evaluate the actual effect of plastics recycling on conserving such inputs. This would be the precondition to assessing what role, if any, plastics recycling has on actual preservation of things that matter in the U.S. (such as coastal communities, Indigenous peoples’ lands, and/or arctic wildlife refuges).

Frequent assumptions are being made among well-intentioned members of the media, environmental organizations, and concerned individuals that actual, current recycling efforts are part of real world protection. In more specialized discussions around Zero Waste and Circular Economy, there is a rolling process of coming to terms with hints that assumptions of conservation and preservation don’t hold. If, for example, we are dismayed to learn that plastics are “downcycled,” our dismay betrays a faith in the assumption of preservation in the background. If only plastic bottles could be produced in a closed-loop fashion, we reason, then we would be able to conserve at least some of the resources that would otherwise be extracted. Presumably, such conservation is needed for ecosystemic preservation, not just to boost the economic fortunes of the plastics industry.

Now let’s turn to the huge, multinational firms in the petrochemical industry that drill for the precursor materials for plastics at the beginning of the production chain. Let’s say more Americans recycled their plastics, and this resulted in an influx of more recycled plastic onto the market. Even with robust closed loops achieved, does anyone really think that the executives at one of these multinationals would get to the point of saying, “well, you know, it’s good that the need for input materials is being met by recycled plastic, and that means that this year we can scale back production a bit. We don’t need to open up a new offshore platform. It isn’t required to meet society’s needs after all!”

Ultimately, this would have to be the scenario in which more and more recycling of plastics actually preserved things that matter ecologically and socially. Yet very little of the empirical work needed to trace materials flows exists in the area of plastics recycling, in part because of a dearth of data.16 And in the area of plastics waste we have perhaps the most egregious misuse of claims that recycling is going to address problems related to pollution and climate change. The industry, and affiliated academic researchers, carry out life-cycle analyses that are impeccable in their methodological approach to quantifying different energy and material requirements associated with primary and secondary flows of plastics.17

None to my knowledge, however, answer the question of what more plastics recycling would do to diminish overall ecosystem withdrawals of fossil fuels. Does tar-sands extraction slow as a result? How about pipeline construction? Perhaps, with improved plastics recycling, we don’t need a Northeast U.S. expansion of storage capacity for hydrofractured natural gas. Not yet? Well, then, what are the plans for the scaleback?

Ideological Implications

These are both empirical and ideological questions. 18 They are ideological because a general optimism about recycling as earth-saving has become internalized in the thought processes of children and adults genuinely concerned about preservation. In everyday speak, assumptions of conservation and preservation swirl in a distant, misty background. In order to preserve optimism, can-doism, and a solutions oriented outlook it is easier not to look into these depths. In fact, critique of recycling’s earth-saving claims falls harshly on concerned ears, leaving bewilderment and a sense of betrayal. Sometimes, it is met with a binary response: either recycling is part of an overall process of saving resources and saving energy and by extension it’s saving the planet, or it’s a waste of time and it’s a sham and a lie.