Chapter 13: Rhetorical Analysis

“We live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, political groups. I ask, in my writing, ‘What is real?’ Because unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudo realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms.”

—Philip K. Dick

What is Rhetorical Analysis?

Unlike a straightforward summary, rhetorical analysis does not only require a restatement of ideas; instead, you must recognize rhetorical moves that an author is making to persuade their audience to do or think something. The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain what is happening in the text, why the author might have chosen to use a particular move or set of rhetorical moves, and how those choices might affect the audience. The text you analyze might be explanatory, although there will be aspects of argument because you must negotiate with what the author is trying to do and what you think the author is doing.

Media is one of the most important places where this kind of analysis needs to happen. Rhetoric is what makes media work. Think of all the media you see and hear every day: social media, television shows, web pages, billboards, text messages, podcasts, and more. Media is constantly asking you to buy something, act in some way, believe something to be true, or interact with others in a specific manner. Understanding rhetorical messages is essential to help us become informed consumers, but it also helps evaluate the ethics of messages, how they affect us personally, and how they affect society.

Because media rhetoric surrounds us, it is important to understand how rhetoric works. If we refuse to stop and think about how and why it persuades us, we can become mindless consumers who buy into arguments about what makes us value ourselves and what makes us happy.

Exercise 13.1

Watch the Mad Men advertising pitch for “The Kodak Carousel,” below, and think about the way the advertisers use images and language to persuade…this is rhetoric!

Answer the following questions

- What is it about the advertising pitch that is supposed to connect with the public and get them to buy the product, in this case the Kodak Carousel?

- What is it about nostalgia (Don Draper said in Greek it means “the pain of an old wound”) that is more powerful than memory?

- Is the advertising pitch by Don Draper effective at persuading the public? Why or why not?

Evaluating an Argument’s Rhetorical Situation

A rhetorical analysis considers all elements of the rhetorical situation—the author, audience, purpose, content, and context—within which a communication was generated and delivered to make an argument about it. A rhetorical analysis will also consider the Kairos, or time, place, and public conversations surrounding the text during its original generation and delivery; the text may also be analyzed within a different context such as how a historical text would be received by its audience today. In rhetorical analysis of a text, consider how the text approaches each element of the rhetorical situation. For each element, does the author demonstrate an understanding of how each element functions within the argument to successfully achieve the text’s purpose?

Evaluating the Argument’s Purpose

All authors set out with a purpose in mind. It might be to share a moment in their life, to argue for lower taxes, to analyze how we, culturally, regard the disabled, or any number of other goals. Everything in the analysis should come right back to that purpose because every choice the author made in crafting the text should be to help achieve that purpose.

To evaluate the purpose of the argument, ask the following questions:

- What seems to be the reason for its existence?

- Is it an argument?

- Is it attempting to persuade you to do or buy something (even if it’s to “buy” an idea)?

- What does the writer/creator seem to want the audience to think, do, or feel (nothing is done in a vacuum – there is always a purpose for something to exist; sometimes it just takes some digging or a change in POV to understand)?

Evaluating the Argument’s Context

![]() According to Chapter 2, context refers to what is happening outside of the text that caused the need for the thing to exist or affected what was said/presented in the text. Before we begin to analyze how the text was crafted, readers must know the situation in which it was written. This may mean doing a bit of research into the original publication location (a textbook, a journal, the internet, etc.) and time.

According to Chapter 2, context refers to what is happening outside of the text that caused the need for the thing to exist or affected what was said/presented in the text. Before we begin to analyze how the text was crafted, readers must know the situation in which it was written. This may mean doing a bit of research into the original publication location (a textbook, a journal, the internet, etc.) and time.

To evaluate the context of the argument, ask the following questions:

- What is the situation that prompted the writing of this text? What was going on at the time? Can you think of any social, political, or economic conditions that were particularly important?

- What background information on the topic or associations with the topic would a reader of this time period likely have?

- Part of the context is the “conversation” the text is part of. It’s unlikely the author is the first person to write on a particular topic. As Graff and Birkenstein point out, writers invariably add their voices to a larger conversation. How does the author respond to other texts? How does she enter the conversation? How does the author position herself in relation to other authors?

- How does the knowledge of the text’s original context influence our reading of it? How have circumstances changed since it was written?

Evaluating the Argument’s Content

As noted in Chapter 2, the content may seem unimportant, but your analysis will reveal how essential elements of content can be to the cohesion and persuasiveness of a text. The author’s choice of content presentation can contribute or detract from the argument’s effectiveness.

To evaluate the content of the argument, ask the following questions:

- Is there a beginning, middle, and an end? A thesis sentence?

- Is the text formal, like a published academic article, or more informal, like a story?

- Does the writer/creator use chronological or spatial order?

- Are visual (pictures, graphs, diagrams, etc.) included?

- Does the writer/creator use quotes and are those quotes smoothly incorporated?

Evaluating the Argument’s Audience

An audience is anyone or group who receives the text. In addition to audience engagement, analysis of a text’s audience will help you identify what level of knowledge the audience is expected to have, the attitude or position of the audience toward the topic, and the reasoning behind some of the author’s rhetorical moves. In addition, understanding the intended audience of a text can help you determine if you are a part of that intended audience or not. In addition to evidence from within the text, audience can also be determined based on the text’s setting and purpose.

An audience is anyone or group who receives the text. In addition to audience engagement, analysis of a text’s audience will help you identify what level of knowledge the audience is expected to have, the attitude or position of the audience toward the topic, and the reasoning behind some of the author’s rhetorical moves. In addition, understanding the intended audience of a text can help you determine if you are a part of that intended audience or not. In addition to evidence from within the text, audience can also be determined based on the text’s setting and purpose.

Any text has potentially at least three audiences, though some of these audiences may be the same. The audience may be one of these three types or a combination of audiences.

- The intended audience — who the author meant to read the text. As mentioned above, whom the text is written for can often be determined by understanding the setting and purpose of a text. For instance, Informed Arguments as a textbook is intended to be read by students, instructors, textbook reviewers, and course designers.

- The implied audience — who the text seems to be addressing in the text. This is often more evident in literary texts, where, for instance, a poet may be addressing a lover, though the intended audience is the readers of the book rather than an actual lover. In non-literary texts, however, an implied audience is often indicated using second person. Oftentimes the intended and implied audiences overlap but are not identical. This textbook, for instance, has an implied audience of students in a rhetoric and composition course, though the intended audience is a bit broader. One of the indicators of the implied audience is the use of “you” and the imperative mood (commands).

- The actual audience — who actually reads the text. In many cases, a text may move beyond the intended audience and the implied audience and be read by people whom the author may not expect. This is particularly true of older texts — as authors can’t really predict how culture and history will unfold, there is a good chance, for instance, that things considered common knowledge in the past may need more explanation now. If you are a part of the actual audience of a text, but not part of the intended audience, you may need to do slightly more work and perhaps background research to understand the text more fully.

To evaluate the audience of the argument, ask the following questions:

- Who is this written/created for? Be specific. Look at the language, suggestions, evidence, and other elements of the argument to determine to whom the argument is addressed.

- Is it written for people like or unlike you?

- Is the audience sympathetic or hostile, educated or naïve?

- Is the audience like or unlike the author?

- Where did you discover the details about the audience (in the text itself; where the text was published; author’s biography, etc.)?

- Where was it published?

- What to other texts are connected to it, and what do they together reveal about the evidence?

- What is the author trying to accomplish? And who would be able to make a difference?

Evaluating the Argument’s Author

This will be explored further in discussions of ethos below. For now, make sure you do a Google search for your author to learn what you can about them. What have they published before? What is their experience or education in the argument topic? What relevant facts can you find out about this author?

Evaluating an Argument’s Rhetorical Appeals

Evaluating an Argument’s Logos

When you evaluate an appeal to logos, you consider how logical the argument is and how well-supported it is in terms of evidence. You are asking yourself what elements of the essay or speech would cause an audience to believe that the argument is (or is not) logical and supported by appropriate evidence. When an author relies on logos, it means that they are using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact checked (using multiple sources) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

When you evaluate an appeal to logos, you consider how logical the argument is and how well-supported it is in terms of evidence. You are asking yourself what elements of the essay or speech would cause an audience to believe that the argument is (or is not) logical and supported by appropriate evidence. When an author relies on logos, it means that they are using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact checked (using multiple sources) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

An argument in its most basic form consists of three parts:

- A claim

- Reasons to support the claim

- Evidence to support the reasons

In some cases, including only these three components will be sufficient to demonstrate the merits of an argument’s ideas and persuade the reader, but in others the argument will need to go beyond these by incorporating counterarguments, backing, qualifiers, and warrants (see Chapter 11 for definitions of these terms). Evaluating the logos of an argument goes beyond looking at the facts or statistics of an argument. You must examine each element of the argument to determine its effectiveness.

Evaluating Claims

A claim, as defined in Chapter 11, is a position or stance that the person communicating takes on an issue. This is the thesis or main claim or main idea in an argument essay. In a rhetorical analysis, your goal is to evaluate the quality of the claim made in the argument. Is it clear, logical, and effective?

To evaluate the quality of a claim, consider the following:

- Is the claim clearly and specifically stated? Clarity and specificity are key to ensuring that the claim’s intent and scope will be understood, so beware of using vague and/or broadly stated claims.

- Does the claim state an idea that someone not only could debate but also would want to debate? If someone would be uninterested in debating the idea, then it matters little that he/she could do so.

- Does the claim state an idea that can effectively be supported? If (sufficient and scholarly) evidence is unavailable to support a claim, then it may be worthwhile to reconsider the claim’s phrasing and/or scope so that it can be revised to state an idea that can be supported more fully.

Evaluating Reasons

Reasons are defined as the author’s supporting opinions for why the claim (the thesis) is true. In other words, the reasons explain why the claim (i.e., thesis) is correct. Thus, an evaluation of an argument must consider the reasons posed in support of the argument’s overarching claim.

Reasons are defined as the author’s supporting opinions for why the claim (the thesis) is true. In other words, the reasons explain why the claim (i.e., thesis) is correct. Thus, an evaluation of an argument must consider the reasons posed in support of the argument’s overarching claim.

To evaluate the quality of reasons, ask the following questions:

- Who is the intended audience, and what kinds of reasons are they most likely to be persuaded by? The ultimate purpose of the argument is to demonstrate the merits of the claim, so, without carefully considering who the audience is for the argument and what will appeal to them, that purpose is unlikely to be met.

- How contentious is the claim (i.e., is the claim more likely to be positively or negatively received by the intended audience), and what does that suggest in terms of not only the kinds of reasons that are needed but also the amount? If the claim reflects an unpopular opinion, then for the argument to succeed, it may need quality reasons and many of them.

- Are the reasons clearly connected to the claim? If it is not apparent how a reason supports the claim, then further information may be needed to show the relationship between them.

- Which reasons are the strongest, and which are the weakest? The strength of the reasons should be an important factor when determining the organization of the argument since it can impact how the audience interprets and responds to the argument.

- How complex are the reasons? Just as it is important to consider the strength of the reasons when determining the organization of the argument, it is also necessary to consider their complexity. Some reasons will be simpler to understand, and others will be more nuanced; what is the best ordering of the reasons to maximize each of their contributions to the argument?

Evaluating Evidence

An argument should present a main claim (i.e., thesis), reasons to support that thesis, and then evidence to support the reasons. Evidence can consist of facts and statistics, but—as noted in Chapter 11, evidence can also consist of anecdotes, expert testimony, case studies, and other types of evidence as well.

First, consider how each reason in the paper is supported. The author may use experience or source material in providing evidence to appeal to logos. While outside sources will provide an argument with excellent evidence in an argumentative essay, in some situations, it can be effective to share personal experiences and observations. Just make sure they are appropriate to the situation and are presented in a clear and logical manner.

Second, determine if the text maintains clear lines of reasoning throughout the argument. One error in logic can negatively impact the entire position. When the argument presents faulty logic, it loses credibility.

Third, if an argument gives evidence, we need to know if the evidence is enough. A few examples may not be representative of a general pattern. If the argument makes a sweeping generalization based on one or two anecdotes or solely on the writer’s own experience, it can be considered a hasty generalization.

How do we decide when the evidence is enough? The science of statistics addresses this question in very specific, technical ways that are worth learning but beyond the scope of this book. Often, however, an intuitive assessment will be enough. We all probably already guard against this fallacy when we search online for products that have been reviewed many times. Clearly one five-star review could be a fluke, but 2,000 reviews averaging 4 1/2 stars is a more reliable indicator.

Finally, examine the facts for any manipulative appeal to logos. Pay attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the facts. Remember: What initially looks like a fact may not actually be one. Maybe you’ve heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985. If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports the common worry of the dissolution of the American family.

To evaluate the quality of evidence, ask the following questions:

- What type of evidence is used? Is it statistical data, expert testimony, anecdotal evidence, or case studies?

- Is the evidence sufficient? Is there enough evidence to convincingly support the claim? Are there multiple pieces of evidence provided?

- Does the argument avoid sweeping generalizations?

- Is the evidence specific and detailed? Does the evidence provide enough detail to be convincing?

- How is the evidence connected to the claim? Is the link between the evidence and the claim clear and logical? Are the warrants (the reasoning that connects the evidence to the claim; see Chapter 11, Toulmin Model) explicitly stated?

- Does the argument address counterevidence? Does the argument consider and refute evidence that might oppose the claim? How effectively are counterarguments and rebuttals presented?

Exercise 13.2

The debate about whether college athletes, namely male football and basketball players, should be paid salaries instead of awarded scholarships is one that regularly comes up when these players are in the throes of their respective athletic seasons, whether that’s football bowl games or March Madness. While proponents on each side of this issue have solid reasons, you are going to look at an article that is against the idea of college athletes being paid.

Take note: Your aim in this rhetorical exercise is not to figure out where you stand on this issue; rather, your aim is to evaluate how effectively the writer establishes a logical appeal to support his position, whether you agree with him or not.

See the article here (https://tinyurl.com/y6c9v89t).

Step 1: Before reading the article, take a minute to preview the text, a critical reading skill explained in Chapter 1.

Step 2: Once you have a general idea of the article, read through it and pay attention to how the author organizes information and uses evidence, annotating or marking these instances when you see them.

Step 3: After reviewing your annotations, evaluate the organization of the article as well as the amount and types of evidence that you have identified by answering the following questions:

- Does the information progress logically throughout the article?

- Does the writer use transitions to link ideas?

- Do ideas in the article have a clear sense of order, or do they appear scattered and unfocused?

- Was the amount of evidence in the article proportionate to the size of the article?

- Was there too little of it, was there just enough, or was there an overload of evidence?

- Were the examples of evidence relevant to the writer’s argument?

- Were the examples clearly explained?

- Were sources cited or clearly referenced?

- Were the sources credible? How could you tell?

Evaluating an Argument’s Pathos

Philosophers and laypeople have long asked what role emotions should have in shaping our ideas. Is it right for arguments to appeal to emotion, or is it a cheap trick? Should we guard against feeling what an argument asks us to feel? Or should we let emotions play a role in helping us decide whether we agree or not?

In one oversimplified view, logic is a good way to decide things and listening to emotions is a bad way. We might make this assumption if we tell ourselves or others, “Stop and think. You’re getting too emotional.” According to this view, no one reasons well under the influence of emotion. Pure ideas are king, and feelings only distort them.

Of course, sometimes emotions do lead us astray. But emotions and logic can work together. Consider Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. Was it illegitimate for him to ask listeners to feel deeply moved to support racial equality? He famously proclaimed, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Should listeners have guarded themselves against feeling sympathy for those four children? If we care about things that matter and an argument is about something that matters, then we will and should have feelings about it. King intertwines his logical argument against racism with an appeal to our empathy, tenderness, and sense of justice.

In analyzing emotional appeals, remember that emotional appeals can be a useful and appropriate way to engage the audience. However, pathos can also be inappropriately applied or overused.

Evaluating Tone and Emotional Appeals

Tone refers to the overall emotional attitude of the argument. We know intuitively what “tone of voice” means when we’re describing a conversation. If we hear a person speaking and ask ourselves the following questions, we will usually be able to describe the tone:

- What emotions are conveyed by the sound of the voice?

- What expression do we see or imagine on the speaker’s face as they make the argument?

When we read, we lack visual and auditory clues, but we still intuitively sense the writer’s attitude. Tone comes across through emotional word choice and choice of examples, but also in other ways, both subtle and overt. These include sentence structure, use of questions, emphasis, and direct declarations of feeling. All of these contribute to an overall pattern.

The writer may be shifting tone and emotional appeal in subtle or dramatic ways either to match shifts in the ideas or to create variety. For example, we think of Shakespearean drama as exalted high culture, but Shakespeare famously wrote scenes of terrible puns, sex jokes, and plenty of slapstick into his most intense tragedies to keep the audience from pelting actors with rotten tomatoes. Similarly, a writer may choose to offer some relief or distraction after an impassioned appeal through a moment of humor or a neutral statement.

We can liken the variety in emotional appeal to the way music varies in volume and pacing. Sometimes a piece of music keeps the same volume and pace throughout, but more often the composer adds notes to the musician on when to boom or hush, hurry or draw out the notes. Sometimes the music gets faster and louder toward the end, in a crescendo of intensity. This is one traditional way of ending an argument: on what we sometimes call a “ringing note” meant to inspire and fire up readers to agree, remember, or take action.

In evaluating an argument, consider the role emotion plays in presenting and arguing for the claim and reasons. Does the author use emotional appeals or not? Should the author have used emotional appeals?

To evaluate tone and emotional appeals, ask the following questions:

- How does the writer feel about the topic of the argument?

- How does the writer feel about their own knowledge of the topic?

- What is the writer’s attitude toward the reader?

- What words and phrases show us these feelings? Which words or phrases demonstrate the author’s tone?

- Does the author use a single emotional appeal throughout the argument or does the author vary the appeals used?

- Which emotions does the author rely upon throughout the argument (e.g., humor, personal connection, empathy, fear, patriotism, etc.)?

Exercise 13.3

Evaluating Emotions and Audience

An argument’s success will depend not just on how well the writer expresses emotion but on how well the writer gauges the reader’s likely response. Values, cultural beliefs, and life experiences shape our emotional reactions. While some appeals to our feelings, such as the reference to parents’ desire to protect their children, may be more universal, others will be more audience specific. Different readers can have opposite emotional reactions to the same sentence. When the writer misjudges readers’ values, assumptions, or experiences, an emotional appeal may fall flat or may hurt the argument instead of helping. An obvious example is a racist or sexist comment.

To evaluate emotions and the audience, ask the following questions:

- Are the emotional appeals (or lack of emotional appeals) appropriate for the audience?

- Are emotional appeals balanced against the values and beliefs of the audience?

- Has the author judged the audience’s values correctly and used emotional appeals effectively?

Evaluating the Legitimacy of an Emotional Appeal

We made the case in Chapter 12 that emotion is a legitimate part of argument, but that emotional appeals can be abused. If a writer knows there is a problem with the logic, they may use an emotional appeal to distract from the problem. Or, a writer may create a problem with the logic, knowingly or unknowingly, because they cannot resist including a particularly strong emotional appeal. In Chapter 12, we also looked at fallacies, or problems with arguments’ logic. Many of the fallacies we have already looked at are so common because the illogical form of the argument makes a powerful appeal. The writer chose the faulty reasoning because they thought it would affect readers emotionally. Arguments that focus on a “red herring,” for example, distract from the real issue to focus on something juicier. A straw man argument offers a distorted version of the other side to make the other side seem frighteningly extreme.

To be legitimate, emotional appeals need to be associated with logical reasoning. Otherwise, they are an unfair tactic. The emotions should be attached to ideas that logically support the argument. Writers are responsible for thinking through their intuitive appeals to emotion to make sure that they are consistent with their claims.

Emotional appeals should not mislead readers about the true nature or the true gravity of an issue. If an argument uses a mild word to describe something horrific, that means the argument can’t connect its emotional appeal to any logical justification. A euphemism is a substitute neutral-sounding word used to forestall negative reactions. For example, calling a Nazi concentration camp like Auschwitz a “detention center” would certainly be an unjustifiable euphemism. Given the amount of evidence about what went on at Auschwitz, using the phrase “Death Camp” would be a legitimate emotional appeal.

A more controversial question is what to call the places where people are detained if they are caught trying to cross the U.S. border without permission. An argument calling U.S. Customs and Border Patrol detention centers to “concentration camps” would need to justify its comparison by arguing for significant similarities. Otherwise, critics would claim that the comparison was a cheap shot intended to make people horrified by detention centers without good reason. Even if the argument simply called the centers “camps,” the word would still bring to mind Nazi concentration camps and also the Japanese internment camps created by our own government during World War II. The word “camp,” when referring to a place where people are held against their will, has inevitable overtones of racism and genocide. An argument should only choose a word with connotations that it can stand by and explain.

To evaluate the legitimacy of an emotional appeal, ask the following questions:

- Is the emotional appeal relevant to the argument’s main point?

- Does the emotional appeal address the audience’s values and beliefs appropriately?

- Are the emotions being invoked based on accurate information or facts?

- Does the emotional appeal rely on any false or misleading information?

- Is the appeal being used to manipulate the audience’s feelings unjustly?

- Does the argument exploit the audience’s fears, hopes, or prejudices?

- Is the emotional appeal balanced with logical reasoning and evidence?

- Does the argument rely too heavily on emotion at the expense of rationality?

Exercise 13.4

In the movie Braveheart, the Scottish military leader, William Wallace, played by Mel Gibson, gives a speech to his troops just before they get ready to go into battle against the English army of King Edward I.

See clip here (https://youtu.be/h2vW-rr9ibE, transcript here). See clip with closed captioning here.

Step 1: When you watch the movie clip, try to gauge the general emotional atmosphere. Do the men seem calm or nervous? Confident or skeptical? Are they eager to go into battle, or are they ready to retreat? Assessing the situation from the start will make it easier to answer more specific, probing rhetorical questions after watching it.

Step 2: Consider these questions:

- What issues does Wallace address?

- Who is his audience?

- How does the audience view the issues at hand?

Step 3: Next, analyze Wallace’s use of pathos in his speech.

- How does he try to connect with his audience emotionally? Because this is a speech, and he’s appealing to the audience in person, consider his overall look as well as what he says.

- How would you describe his manner or attitude?

- Does he use any humor, and if so, to what effect?

- How would you describe his tone?

- Identify some examples of language that show an appeal to pathos: words, phrases, imagery, collective pronouns (we, us, our).

- How do all of these factors help him establish a pathetic appeal?

Step 4: Once you’ve identified the various ways that Wallace tries to establish his appeal to pathos, the final step is to evaluate the effectiveness of that appeal.

- Do you think he has successfully established a pathetic appeal? Why or why not?

- What does he do well in establishing pathos?

- What could he improve, or what could he do differently to make his pathetic appeal even stronger?

Evaluating an Argument’s Ethos

So far, we have discussed how arguments attempt to affect our emotions and attempt to persuade with logic, but an argument’s success also depends on how well writers have gauged their readers’ values and cultural associations. Now we can back up and look at readers’ responses through a different lens: that of trust. Trust provides an underlying foundation for the success of emotional and logical appeals. If we don’t have a certain degree of trust in the writer, we will be less willing to let an argument affect us. We may not allow even a skillfully worded emotional appeal to move us, and we may not be ready to agree even with a well-supported claim.

So far, we have discussed how arguments attempt to affect our emotions and attempt to persuade with logic, but an argument’s success also depends on how well writers have gauged their readers’ values and cultural associations. Now we can back up and look at readers’ responses through a different lens: that of trust. Trust provides an underlying foundation for the success of emotional and logical appeals. If we don’t have a certain degree of trust in the writer, we will be less willing to let an argument affect us. We may not allow even a skillfully worded emotional appeal to move us, and we may not be ready to agree even with a well-supported claim.

To evaluate the author’s authority, ask the following questions:

- Is the author a highly educated expert on that topic who is choosing to publish an article for a popular, mainstream audience?

- Is the author a journalist who specializes in the topic? A journalist whose specialty is unclear? A citizen who is weighing in?

- Is the author writing from personal experience, or are they synthesizing and offering commentary on others’ experiences?

Each of these different levels of expertise will confer a different level of authority on the topic. It is important to understand if an author is truly an expert on the content.

Be careful that you are not using an article that is actually a middle school student essay published in a school newspaper!

Evaluating Bias (Author and Publication)

Bias means presenting facts and arguments in a way that consciously favors one side or other in an argument.

Is bias bad or wrong?

No!

Everyone who argues strongly for something is biased. You mustn’t assume that because a person writes with a particular bias they are not being sincere, or that they have not really thought the issue through. The person is not just stating what they think; they are trying to persuade you about something.

Bias can result from the way someone has organized their experiences in their own mind. Perhaps they have lumped some experiences into the ‘good’ box and some experiences into the ‘bad’ box. Just about everybody does this. Everyone has various biases on any number of topics. For example, you might have a bias toward listening to music radio stations rather than talk radio or news programs. You might have a bias toward working at night rather than in the morning or working by deadlines rather than getting tasks done in advance. These examples identify minor biases, of course, but they still indicate preferences and opinions.

Defining “Left” and “Right” Bias

First, let’s define what Americans mean when they say someone or something is politically biased. When describing potential bias in media reporting, people often talk about bias toward the “left” or “right”. The terms “left” and “right” appeared during the French Revolution of 1789 when members of the National Assembly divided into supporters of the king to the president’s right and supporters of the revolution to his left. Ever since, “left wing” has tended to refer to more progressive political positions and “right wing” to more conservative stances.

In U.S. politics, the major divide between left and right has to do with the role of government: left wing politics tend to support more government intervention toward greater social equality, whereas right wing politics tend to favor a smaller role for government and greater economic freedom for individuals and businesses.

Conservative vs. Liberal Defined

This link offers an overview of liberal and conservative views, but please keep in mind that these boxes are not applicable in every instance. Political ideology is considered a spectrum, which means it is not either/or. For example, you might identify with some liberal beliefs and some conservative beliefs, or you might align completely with one side of the spectrum or the other. The provided link is simply a broad overview to introduce you to these categories that we so often use in labeling our news sources.

Evaluating Author’s Bias

Most reputable websites and news sources will list or cite an author, even though you might have to dig into the site deeper than just the section you’re interested in to find it. Most pages will have a home page or “About Us”/”About This Site” link where an author will be credited

Often, understanding the author’s bias or authority will require some research that goes well beyond any blurb that might be included with the actual article. Google the author or consider looking at their LinkedIn profile. Look at several different sources instead of relying on just one website to understand who the author is.

To evaluate an author’s bias, ask the following questions:

- Does the author support a particular political or religious view that could be affecting his or her objectivity in the piece?

- Is the author supported by any special-interest groups (i.e. the American Library Association or Keep America Safe)?

- Does the author discuss alternative viewpoints on the issue?

- Examine the discussion of emotional appeals above? Is the emotional appeal legitimate or not?

Evaluating Publication Ideology and Bias

All publications choose which articles to publish and how much to emphasize them. However, when the article selection process distorts what the audience perceives as important or true, this becomes a form of bias. For example, editors may place new articles with still-developing stories more prominently than they do follow-up articles that complete the picture. Similarly, scholarly articles that try to reproduce the results of prior research have a harder time getting published than articles with new research questions.

When reading or watching the news, it can be useful to know whether a particular media entity or author or publication skews to the left or right. Political bias in one direction or another may not make the news less factual or truthful, but it can change the emphasis of the coverage and the way certain issues are framed. Below, we will discuss how to identify author and publication political bias.

To evaluate a publication’s bias, ask the following questions:

- Does the publication have an ideological bias? (conservative? liberal?)

- Is the publication religious? Secular?

- Is the publication created for a very specific target audience?

- If you are looking at a website, what is its purpose? Was the site created to sell things, or are the authors trying to persuade voters to take a side on a particular issue?

- There are many different types of bias. Check out this article from All Sides, “How to Spot 16 Types of Media Bias” for a list of different types of biases to look for in the media. Are any of these biases evident in the article or publication?

Exercise 13.5

|

Coverage |

Unbiased: This source’s information is not drastically different from coverage of the topic elsewhere. Information and opinion about the topic don’t seem to come out of nowhere. It doesn’t seem as though information has been shaped to fit. |

Biased: Compared to what you’ve found in other sources covering the same topic, this content seems to omit a lot of information about the topic, emphasize vastly different aspects of it, and/or contain stereotypes or overly simplified information. Everything seems to fit the site’s theme, even though you know there are various ways to look at the issue(s). |

|

Citing Sources |

Unbiased: The source links to any earlier news or documents it refers to. |

Biased: The source refers to earlier news or documents, but does not link to the news report or document itself. |

|

Evidence |

Unbiased: Statements are supported by evidence and documentation. |

Biased: There is little evidence and documentation presented, just assertions that seem intended to persuade by themselves. |

|

Vested Interest |

Unbiased: There is no overt evidence that the author will benefit from whichever way the topic is decided. |

Biased: The author seems to have a “vested interest” in the topic. For instance, if the site asks for contributions, the author probably will benefit if contributions are made. Or, perhaps the author may get to continue his or her job if the topic that the website promotes gets decided in a particular way. |

|

Imperative Language |

Unbiased: Statements are made without strong emphasis and without provocative twists. There aren’t many exclamation points. |

Biased: There are many strongly worded assertions. There are a lot of exclamation points. |

|

Multiple Viewpoints |

Unbiased: Both pro and con viewpoints are provided about controversial issues. |

Biased: Only one version of the truth is presented about controversial issues. |

Evaluating Sincerity

Obviously, lying about who we are or what we believe in is not a valid way to build trust. An appeal to a shared identity that is not really shared or an appeal to a shared value that the writer does not really hold is certainly a breach of trust.

However, referring to an identity that the writer doesn’t share can be a legitimate gesture of goodwill, as long as the writer doesn’t misrepresent their own background. A white politician who interjects Spanish words into a speech to a largely Latinx audience is signaling that they want to appear friendly and empathetic to a Latinx identity. Of course, the politician’s accent may undermine this by reminding the audience of their different backgrounds. Will the audience be glad that the politician is trying? Will they be put off by a sense that the politician is presuming too much or encroaching on an identity that doesn’t belong to them? Writers will often try to signal respect and familiarity if they do refer to another group’s identity, as in “I know from talking to transgender friends that using a single-gender restroom can feel stressful and dangerous.”

To evaluate the sincerity of an argument’s ethos, ask the following questions:

- Does the attempt to get the reader to trust suggest an idea that is not logical or not true?

- How much is the appeal to trust relevant to the argument’s trustworthiness?

- Is the argument asking for more trust than is really warranted?

Even if the attempt to gain our trust is logical and relevant, we should ask whether its importance has been exaggerated. Our decision to trust should be based on many different factors. Often appeals to trust imply that we should accept or reject a claim when more caution is called for.

Exercise 13.6

Choose an article from the links provided below. Preview your chosen text, and then read through it, paying special attention to how the writer tries to establish an ethical appeal. Once you have finished reading, use the bullet points above to guide you in analyzing how effective the writer’s appeal to ethos is.

“Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle” by Xeni Jordan (https://tinyurl.com/y7m7bnnm)

“Relax and Let Your Kids Indulge in TV” by Lisa Pryor (https://tinyurl.com/y88epytu)

“Why are we OK with disability drag in Hollywood?”by Danny Woodburn and Jay Ruderman (https://tinyurl.com/y964525k)

Evaluating for Fallacies

The following examples demonstrate how to evaluate for use of fallacies; for more details about fallacies, see Chapter 12.

Bandwagon Fallacy

An extremely common technique is to suggest that a claim is true because it is widely accepted. Of course, we do legitimately need to refer to other people’s opinions as guides to our own at times. An idea’s popularity may be a legitimate reason to investigate it further. It might be a reason to consider it influential and thus important to address in a discussion. But its popularity does not prove its validity. Popularity may be due to the idea’s correctness, but it may be due to many other reasons too.

Appeals to popularity encourage readers to base their decisions too much on their underlying desire to fit in, to be hip to what everybody else is doing, not to be considered crazy, such as the first time we did something wrong because all of our friends were doing it, too, and our mom or dad asked us, “If all of your friends jumped off a bridge, would you do that too?”

Appeals to popularity encourage readers to base their decisions too much on their underlying desire to fit in, to be hip to what everybody else is doing, not to be considered crazy, such as the first time we did something wrong because all of our friends were doing it, too, and our mom or dad asked us, “If all of your friends jumped off a bridge, would you do that too?”

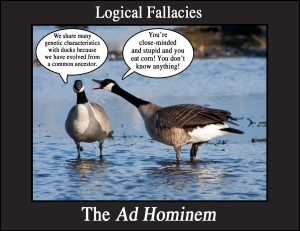

Ad Hominem Fallacy

We commit this fallacy when, instead of attacking an opponent’s views, we attack the opponent. What makes this a fallacy is the disconnect between the reason and the claim. Logicians call this an ad hominem fallacy, which means “to the person.” The opponent may have bad qualities, but these qualities do not make their argument incorrect. They may give legitimate reason to trust the argument less, but they do not invalidate it.

This fallacy comes in various forms; there are a lot of different ways to attack a person while ignoring (or downplaying) their actual arguments. Abusive attacks are the most straightforward. The simplest version is simply calling your opponent names instead of debating them. Donald Trump mastered this technique. During the 2016 Republican presidential primary, he came up with catchy nicknames for his opponents, which he used just about every time he referred to them: “Lyin’ Ted” Cruz, “Little Marco” Rubio, “Low-Energy Jeb” Bush. If you pepper your descriptions of your opponent with tendentious, unflattering, politically charged language, you can get a rhetorical leg-up.

Guilt by Association

Another abusive attack is guilt by association. Here, you tarnish your opponent by associating them or his views with someone or something that your audience despises. Consider the following:

Former Vice President Dick Cheney was an advocate of a strong version of the so-called Unitary Executive interpretation of the Constitution, according to which the president’s control over the executive branch of government is quite firm and far-reaching. The effect of this is to concentrate a tremendous amount of power in the Chief Executive, such that those powers arguably eclipse those of the supposedly co-equal Legislative and Judicial branches of government. You know who else was in favor of a very strong, powerful Chief Executive? That’s right, Hitler.

The argument just compared Dick Cheney to Hitler with only the tiniest shred of evidence. That evidence is not sufficient to make a legitimate comparison: if it were, then any person who favored giving most government power to one leader could be compared to Hitler. Clearly, consolidating power was not the most significant thing Hitler did, nor, in itself, is it the reason we have such negative associations with his name. Those powerful negative associations make comparisons to Hitler and the Nazis a powerful rhetorical strategy which is often used when it isn’t justified. There is even a fake-Latin term for the tactic: Argumentum ad Nazium (cf. the real Latin phrase, ad nauseum—to the point of nausea.

To evaluate the use of fallacies, ask the following questions:

- Does the argument rely solely on its popularity to persuade?

- Does the argument attack the opposition’s character or beliefs while ignoring legitimate concerns or arguments?

- Does the author use “guilt by association” to persuade the audience to disagree with the opposition?

Exercise 13.7

Rhetorical Analysis of a Song

Music is a powerful and prevalent form of rhetoric in our society. We often listen to songs and sing along without always considering the lyrics. Many artists craft their work with specific messages in mind. Consider the album DAMN. by Kendrick Lamar; in 2018, the album won a Pulitzer Prize for Music. The prize has been awarded to musicians since 1943, which further demonstrates the impact music has on our culture.

Choose ONE of your favorite songs to practice rhetorical analysis.

Answer the following questions:

- What is the tone of the song? (Some options: happy, angry, direct, casual, etc.)

- Does the writer/performer have credibility (ethos)? Explain their credibility.

- How is the text of the song organized? Is there a main idea? What is the main idea?

- What is the purpose of the text?

- Who is the audience for the song?

Exercise 13.8

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Prompt Option

Purpose: To combine the rhetorical analysis skills you’ve developed with thematic analysis.

Assignment:

- Select one essay from our text in Part VI.

- Select any theme you find intriguing (the theme is the main idea/focus/argument of the essay).

- Provide textual evidence of that theme in the text and thoroughly explore how the theme is rhetorically developed in the text.

This prompt asks you, essentially, to analyze a theme’s development in one text by focusing on the rhetorical devices/strategies/fallacies the author/creator uses to develop it.

See Chapter 12 for more details about ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos as well as specific lists of devices and fallacies.

You will need to have proper in-text citations and a Work Cited page.

- MLA citation: Chapter 18

Choose only ONE essay from Part VI of the textbook [your instructor may assign specific options]

Specifics:

3-4 pages

- Use MLA format: double spaced, Times New Roman, 12 pt. font

Brainstorming (to help get you started; you are writing an essay, not responding to questions)

- What is the text’s dominant theme (there may be multiple themes; however, choose the most obvious or most intriguing one)?

- What rhetorical choices does the author make (use the rhetorical strategies and logical fallacies lists in “Rhetorical Analysis”)?

- Who is the audience and what is the text’s purpose?

- How does the audience/purpose affect the writer’s rhetorical choices?

- What is socially important about the text?

- Finally, does the text effectively present your chosen theme? Why?

Some hints:

- Stay organized! Though some summary may be necessary to establish your point, assume that I have read the text (which I have).

- Make sure a thesis sentence is established in the first or second paragraph; the thesis should clearly demonstrate your understanding of the theme and rhetorical analysis.

- Keep in mind; you are examining how and why the author developed the text (rhetorical analysis) and what that text implies (theme).

- Remember to avoid “I” and “you” statements in this paper – write in 3rd person academic voice.

- Preferred thesis can be “fill-in-the-blank”: Author X uses [strategies/fallacies]____________________, ______________________, and ______________________ to argue/claim/explain/declare/etc. [main idea/theme of essay]_________________________________________________

Student Example Essay:

Rhetorical Analysis ENG 102 Example Essay_Isabelle Enriquez

Key Takeaways

- Evaluating rhetorical moves within an argument can make us more aware of the persuasive techniques being used to sell us products, services, and ideas.

- Rhetorical analysis can also help us improve our own rhetorical skills by forcing us to examine what works and what does not work in crafting rhetoric.

- Rhetorical analysis involves the evaluation of the rhetorical situation, rhetorical appeals, and fallacies within an argument. This is not the limit of rhetorical analysis; it can involve the examination of all aspects of rhetoric beyond those that we focus on here.

Attributions

“6.2 Rhetorical Analysis” A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“2.6: Rhetorical Analysis” by Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“10.2: Analyzing an Argument’s Situation (Kairos, or the Rhetorical Situation)” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“3.4 WHAT IS THE RHETORICAL SITUATION?” by Robin Jeffrey, Emilie Zickel, Terri Pantuso, Kalani Pattison, and Sarah LeMire is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“9.2: Introduction to Logos” by University of Mississippi is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Logos by Excelsior OWL is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“4.4: Questioning the Assumptions” by Anna Mills is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“32 Rhetorical Analysis” by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“9.3 Bias,” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

“3.9 Bias in Writing” by Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, & Kirk Swenson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“4.6 Investigate the source – bias,” by Iowa State University Library Instruction Services is licensed underCC BY-SA 4.0

“Identifying Bias” by Lumen Learning CC BY 4.0

“4. Rhetorical Analysis Concepts and Strategies” by Liona Burnham is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Spin (propaganda) by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Image Credits

Image of map Photo by Kelsey Knight on Unsplash

Coronavirus stories Photo by Obi – @pixel8propix on Unsplash

The sign on Logic Lane, Oxford Photograph by Jonathan Bowen is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Audience Photo by Josh Sorenson on Pexels

Be reasonable Photo by Victor on Unsplash

Magnifying glass on keyboard Agence Olloweb on UnSplash

Two faces of Buddha Photo by Mark Daynes on Unsplash

Man singing Photo by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu on Unsplash

Sheet music Photo by Pixabay on Pexels

Woman presenting Photo by RF._.studio from Pexels

Schnauzer Photo by andrescarlofotografia from Pixabay

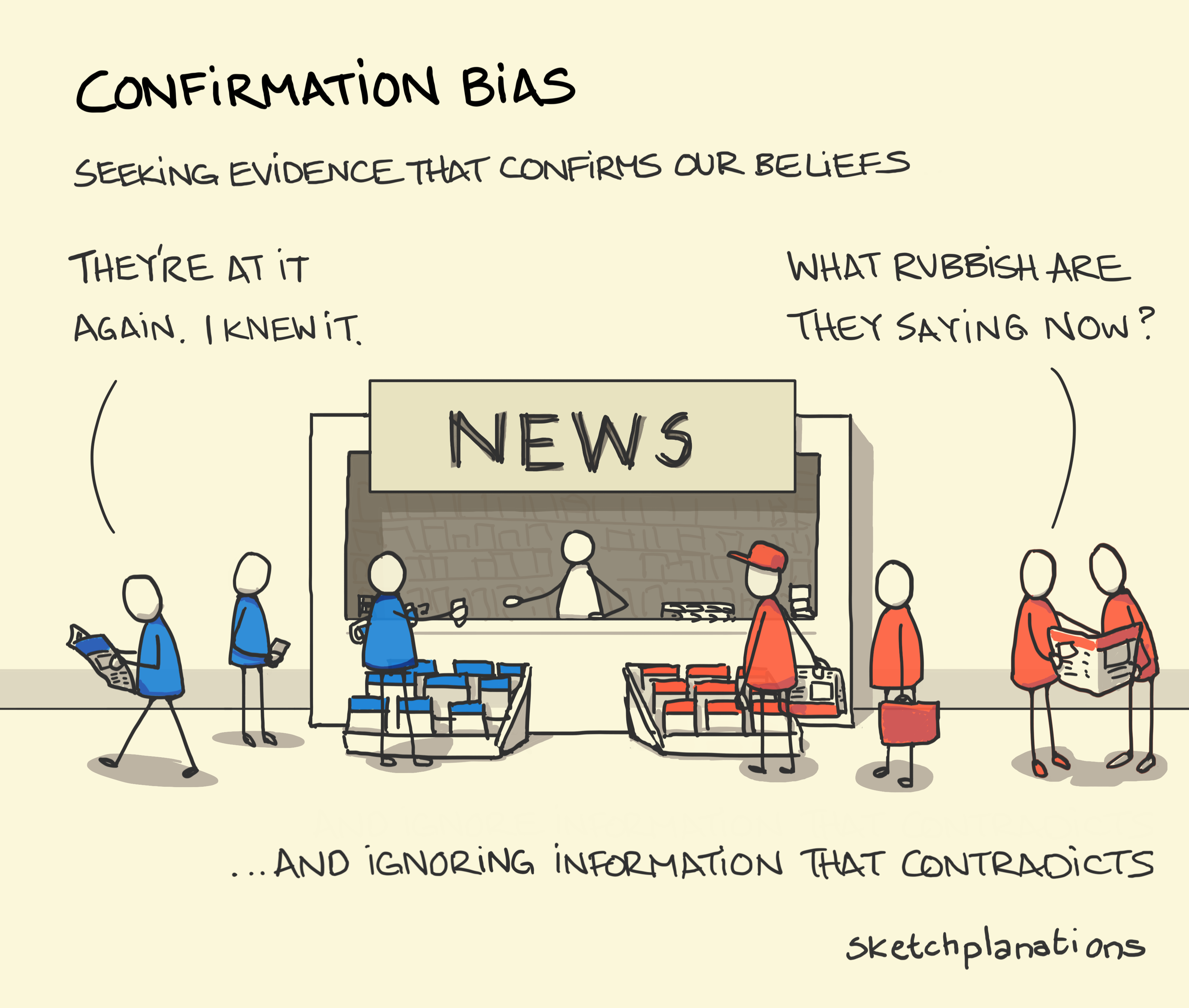

Confirmation Bias by Sketchplanations is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0

Tom Hiddleston as Loki on Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Big group of people Photo by Alex Radelich on Unsplash

Camera Parts Photo by Shane Aldendorff on Unsplash

Logical Fallacy Geese by Mark Klotz on Flikr is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0