Chapter 4: Prewriting

What Is Prewriting?

Prewriting describes all of the thinking and planning that precedes the actual writing of a paper.

Did you ever work on a creative project—paint a picture, make a quilt, build a wooden picnic table or deck? If you did, you know that you go through a development stage that’s kind of messy, a stage in which you try different configurations and put the pieces together in different ways, before you say “aha” and a pattern emerges.

Writing is a creative project, and writers go through the same messy stage. For writers, the development stage involves playing with words and ideas—playing with writing. Prewriting is the start of the writing process, the messy, “play” stage in which writers jot down, develop, and try out different ideas, the stage in which it’s fine to be free-ranging in thought and language. Prewriting is intended to be free-flowing, to be a time in which you let your ideas and words flow without caring about organization, grammar, and the formalities of writing.

As Anne Lamott says in her essay “Shitty First Drafts,” “Almost all writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something—anything—down on paper.”

There are many ways to develop ideas for writing, including:

- Understanding the Assignment

- Choosing a Topic

- Developing Ideas:

- Freewriting

- Journaling

- Mapping

- Probing

- Believing/Doubting

- Focusing a Topic

Understanding the Assignment

Much careful thought needs to be given to the assignment in general at the beginning of prewriting before focusing on your topic.

Before you begin working on an essay or a writing assignment, don’t forget to spend some quality time analyzing the assignment sheet. By closely reading and breaking down the assignment sheet, you are setting yourself up for an easier time of planning and composing the assignment.

Try to fully understand what you need to do:

- Carefully read the assignment sheet and search for the required page length, due dates, and other submission-based information.

- Determine the genre of the assignment. What, in the broadest sense, are you being asked to do? Are you asked to analyze (examine small pieces of the larger whole and indicate what their meaning or significance is), synthesize (draw from and connect several different sources), explain, or persuade (attempt to get a reader to accept your claim)?

- Identify the core assignment questions that you need to answer. Sometimes, a list of prompts or questions may appear with an assignment. It is likely that your instructor will not expect you to answer all of the questions listed. They are simply offering you some ideas so that you can think of your own questions to ask. Circle all assignment questions that you see on the assignment sheet and put a star next to the question that is either the most important OR that you will pursue in creating the assignment.

- Locate the evaluation and grading criteria. Many assignment sheets contain a grading rubric or some other indication of evaluation criteria for the assignment. You can use these criteria to both begin the writing process and to guide your revision and editing process. If you do not see any rubric or evaluation criteria on the assignment sheet—ask!

- Depending on the discipline in which you are writing, different features and formats of your writing may be expected. Always look closely at key terms and vocabulary in the writing assignment and be sure to note what type of evidence and citations style your instructor expects. Does the essay need to be in MLA, APA, or another style? Does the professor require any specific submission elements or formats?

Consider the rhetorical situation, which includes the author, audience, purpose, and context as described in Chapter 2. Thinking rhetorically is an important part of any writing process because every writing assignment has different expectations. There is no such thing as right when it comes to writing; instead, try to think about good writing as being writing that is effective in that particular situation.

Go back to Chapter 2 and spend some time thinking about the rhetorical situation of the assignment. It’s so important to stop and think about what you are being asked to write about and why before you begin an assignment.

The following video presentation will help you as you begin to think about your assignments rhetorically. It’s so important to stop and think about what you are being asked to write about and why before you begin an assignment.

Thinking Rhetorically: Adding Rhetoric to Your Writing Process

Choosing a Topic

The next step in prewriting, and often the hardest, is choosing a topic for an essay if one has not been assigned. Choosing a viable general topic for an assignment is an essential step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A captivating topic covers what an assignment will be about and fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience. There are various methods you may use to discover an appropriate topic for your writing.

The next step in prewriting, and often the hardest, is choosing a topic for an essay if one has not been assigned. Choosing a viable general topic for an assignment is an essential step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A captivating topic covers what an assignment will be about and fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience. There are various methods you may use to discover an appropriate topic for your writing.

Use Experience and Observations

When selecting a topic, you may also want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Use the News

Have you seen an attention-grabbing story on your local news channel? Many current issues appear on television, in magazines, and on the Internet. These can all provide inspiration for your writing.

Our library’s databases like Issues and Controversies, Newsbank, and Opposing Viewpoints in Context can be excellent resources.

Developing Ideas

Once you understand the assignment and choose a topic, you will need to collect information to understand your topic and decide where you want the paper to lead. This step can be conducted in various ways:

- Freewriting

- Journaling

- Mapping

- Listing

- Probing

- Believing/Doubting

Freewriting

Freewriting (also called brainstorming) is an exercise in which you write freely (jot, list, write paragraphs, dialog, take off on tangents: whatever “free” means to you) about a topic for a set amount of time (usually three to five minutes or until you run out of ideas or energy). It’s a way to free up your thoughts, help you know where your interests lie, and get your fingers moving on the keyboard or on the notebook page (and this physical act can be a way to get your thoughts flowing). Jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about what you are saying, how it sounds, whether it is good or true, or if the grammar, spelling, or punctuation are correct. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you are stuck, just copy the same word or phrase repeatedly until you come up with a new thought or write about why you cannot continue. Just keep writing; that is the power of this technique!

You might even try a series of timed freewriting. Set a timer for five minutes. The object is to keep your fingers moving constantly and write down whatever thoughts come into your head during that time. If you can’t think of anything to say, keep writing I don’t know or this is silly until your thoughts move on. Stop when the timer rings. Shake out your hands, wait awhile, and then do more timed freewritings. After you have a set of five or so freewritings, review them to see if you’ve come back to certain topics, or whether you recorded some ideas that might be the basis for a piece of writing.

Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover more ideas about the topic as well as different perspectives on it. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more than your original idea. Freewriting can also be used to narrow a topic and/or to develop supporting ideas once a broad topic has been chosen.

Example of Freewriting

I don’t think this is useful or helpful in any way. This is stupid, stupid, stupid. I’m looking out of my window and it’s the end of May and I can see that white cotton stuff flying around in the air, from the trees. One of my aunts was always allergic to that stuff when it started flying around in the spring. Don’t know offhand what type of tree that comes from. That aunt is now 94 years old and is in a nursing home for a while after she had a bad episode. She seems to have one now every spring. It’s like that old tree cotton triggers something in her body. Allergies. Spring. Trying to get the flowers to grow but one of the neighbors who is also in his 90s keeps feeding the squirrels and they come and dig up everyone’s flowerbed to store their peanuts. Plant the flowers and within thirty minutes there’s a peanut there. Wonder if anyone has grown peanut bushes yet? Don’t know . . . know . . .

Possible topics from this freewrite:

- Allergy causes

- Allergies on the rise in the U.S.

- Consequences of humanizing wild animals

- Growing your own food

Focused Freewriting is freewriting again and again with each freewriting cycle becoming more focused (also called looping), and it can yield a great deal of useful material. Try this by taking the most compelling idea from one freewriting and starting the next with it.

Journaling is another useful strategy for generating topic and content ideas. Journaling can be useful in exploring different topic ideas and serve as possible topic ideas for future papers. Many people write in personal journals (or online blogs). Writers not only record events in journals, but also reflect and record thoughts, observations, questions, and feelings. Journals are safe spaces to record your experience of the world.

Use a journal to write about an experience you had, different reactions you have observed to the same situation, a current item in the news, an ethical problem at work, an incident with one of your children, a memorable childhood experience of your own, etc. Try to probe the why or how of the situation.

Journals can help you develop ideas for writing. When you review your journal entries, you may find that you keep coming back to a particular topic, or that you have written a lot about one topic in a specific entry, or that you’re really passionate about an issue. Those are the topics, then, about which you obviously have something to say. Those are the topics you might develop further in a piece of writing.

Example of a Journal Entry

The hot issue here has been rising gas prices. People in our town are mostly commuters who work in the state capitol and have to drive about 30 miles each way to and from work. One local gas station has been working with the gas company to establish a gas cooperative, where folks who joined would pay a bit less per gallon. I don’t know whether I like this idea – it’s like joining one of those stores where you have to pay to shop there. You’ve got to buy a lot to recoup your membership fee. I wonder if this is a ploy of the gas company?? Others were talking about starting a petition to the local commuter bus service, to add more routes and times, as the current service isn’t enough to address workers’ schedules and needs. Still others are talking about initiating a light rail system, but this is an alternative that will take a lot of years and won’t address the situation immediately. I remember the gas crunch a number of years ago and remember that we simply started to carpool. In the Washington, DC area, with its huge traffic problems and large number of commuters, carpooling is so accepted that there are designated parking and pickup places along the highway, and it’s apparently accepted for strangers to pull over, let those waiting know where they’re headed, and offer rides. I’m not certain I’d go that far…

Possible topics from this journal entry:

- The causes of rising gas prices

- The negative effects of rising gas prices

- The benefits and drawbacks of gas cooperatives

- The benefits of alternative methods of transportation

- The limitations of carpooling

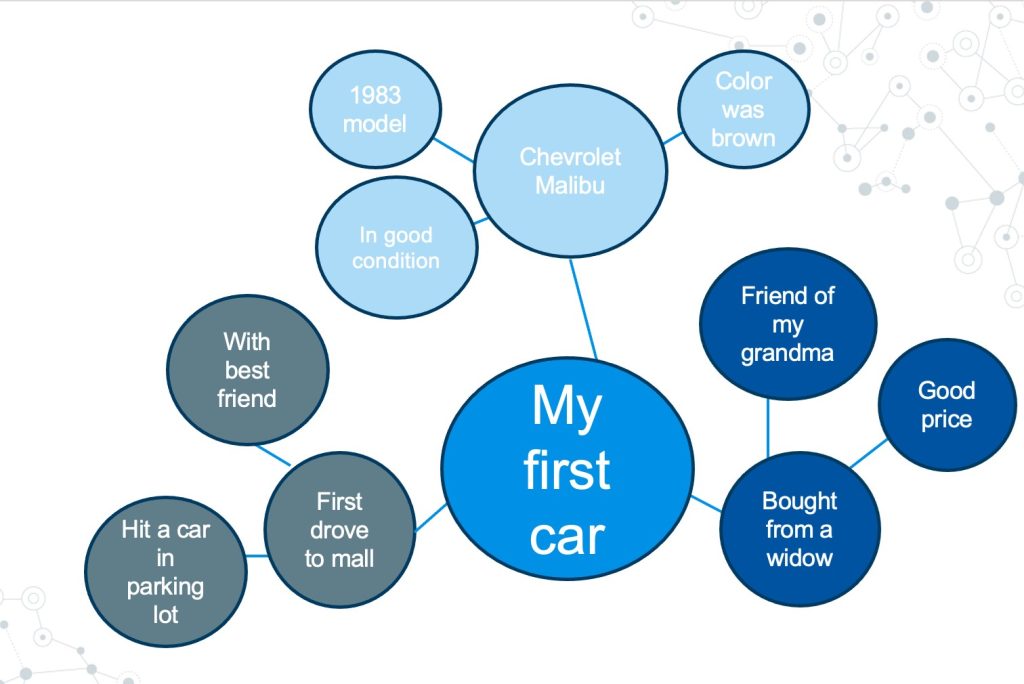

Mapping

Mapping or diagramming helps you immediately group and see relationships among ideas. Mapping and diagramming may help you create information on a topic, and/or organize information from a list or freewriting entries, as a map provides a visual for the types of information you’ve generated about a topic. For example, if I write about the topic of my first car, then I start with a bubble in the middle labeled “my first car.” Then, I branch off from that topic with related ideas, such as the model, where I got it from, and where I drove to first. Branching helps you see the relationship between ideas in a visual format. This can also be used to help you organize your ideas. Mapping often works well for visual learners or right-brain dominant students as it allows all ideas to be seen all at once.

Figure 4.1 Example of mapping for the topic “my first car”

Here are a few online tools that can help with this process:

Example of Using a Combination of Prewriting Strategies

Any prewriting strategies can be used together. For example, you could start by freewriting about the topic and then use the mapping strategy to organize your thoughts. In this screen cast, you’ll see the student share freewriting and mapping.

Listing

Listing may seem simple and rather self-explanatory, but it is an effective strategy to document ideas, especially for students who are left-brain dominant or linear thinkers.

Making a list can help you develop ideas for writing once you have a particular focus. If you want to take a stand on a subject, you might list the top ten reasons why you’re taking that particular stand. Or, once you have a focused topic, you might list the different aspects of that topic.

Example of Listing

Ways to live a greener life:

- Use natural cleaning products without propellants

- Walk or bicycle to places nearby

- Use recycled products

- Take public transportation

- Recycle cans and bottles

- Use non-life-threatening traps instead of chemical squirrel repellents

Probing

Once you choose a general topic, then you must decide on the scope of the topic. Broad topics always need to be narrowed down to topics that are more specific.

Probing is asking a series of questions about the topic: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

Example of Probing

If you were writing about tattoos, then you might ask yourself the following questions:

- Who do you know that has tattoos or who are some celebrities with memorable tattoos?

- What kinds of tattoos do people usually get–what symbols and what words?

- Where do people place tattoos on their bodies or where do people go to get tattoos–tattoo parlors?

- When do people get tattoos–is it after some memorable event or life stage?

- Why do people get tattoos?

- How do people get tattoos–what is the actual process?

Believing and Doubting

Often, you will be asked to write about controversial topics and form opinions about various issues. In this situation, it is important to take the time to truly understand the complexity of both sides of the argument before taking a position. In his book Writing Without Teachers, Peter Elbow introduces the concept of the “believing” and “doubting” games as methods to approaching texts, but this strategy can also be used during the prewriting stage of the writing process.

You would start by writing a controversial statement you plan to address in your essay on a sheet of paper. You would then divide that sheet of paper in two sections and write “Believe It” on one side and “Doubt It” on the other side. For about 10 minutes you would assume that you agree with the statement, suspend all disbelief and explore the reasons to support it. Then you would spend the same amount of time playing the devil’s advocate and disagreeing with the statement, finding flaws, errors, and contradictions.

Engaging in this activity would help you figure out your own bias and allow you to challenge your deeply held beliefs and further understand someone else’s views. This activity promotes the idea that there can be competing truths, and that each point of view has some value. It is also a great way to generate ideas for the future essay.

Focusing a Topic

After pre-writing, you should have an idea of what you want to write about, so you need to stop and consider if you have chosen a feasible topic that meets the assignment’s purpose.

If you have chosen a very large topic for a research paper assignment, you need to create a feasible focus that’s researchable. For example, you might write about something like the Vietnam War, specifically the economic impact of the war on the U.S. economy.

If you have chosen a topic for a non-research assignment, you still need to narrow the focus of the paper to something manageable that allows you to explore the topic in-depth. For instance, you might have a goal of writing about the nursing profession but with a specific focus on what the daily routine is like for a nurse at your local pediatric hospital.

The important thing is to think about your assignment requirements, including length requirements, and make sure you have found a topic that is specific enough to be engaging and interesting and will fit within the assignment requirements.

The following checklist can help you decide if your narrowed topic is a possible topic for your assignment:

- Why am I interested in this topic?

- Would my audience be interested and why?

- Do I have prior knowledge or experience with this topic? If so, would I be comfortable exploring this topic and sharing my experiences?

- Why do I want to learn more about this topic?

- Is this topic specific? What specifics or details about this topic stand out to me?

- Does it fit the purpose of the assignment, and will it meet the required length of the assignment?

Time to Write

If you have never tried out some of these prewriting strategies, it’s a good idea to give them a try, especially if you have writer’s block or feel your current prewriting strategies don’t work well for you. Using your own assignment, spend some time trying out at least two of the prewriting activities described in this section of The Writing Process.

What are your results? What information can you use as you progress with your essay? Which prewriting strategy worked best for you?

You should put the notes you develop from your prewriting activities in a journal or some place that will be handy for you. You can type or handwrite your prewriting, but even after you finish reviewing your notes initially, keep them around, as you may need to come back to them later if an idea you have from the beginning doesn’t work out.

Be sure to share your results with someone, such as a classmate or your professor. Talking about your ideas, especially in this early stage, can really help you develop your ideas in your mind and can help you develop new ideas as well.

For additional prewriting strategies, please review the following handout:

Key Takeaways

- All writers rely on steps and strategies to begin the writing process.

- The steps in the writing process are prewriting, drafting, revising, editing/proofreading, and publishing.

- Prewriting is the transfer of ideas from abstract thoughts into words, phrases, and sentences on paper.

- A good topic interests the writer, appeals to the audience, and fits the purpose of the assignment. Writers often choose a general topic first and then narrow the focus to a more specific topic.

- A strong thesis statement is key to having a focused and unified essay.

- Rough drafts are opportunities to get ideas down onto paper to get a first look at how your ideas will work together.

- Revising improves your writing as far as supporting ideas, organization, sentence flow, and word choices.

- Editing spots and corrects any errors in grammar, mechanics, spelling, and formatting.

- Regardless of the type of assignment you may be given in college or in work, it benefits you to follow a writing process, to put in the work necessary to understand your subject and audience, and to communicate your ideas confidently and coherently.

Attributions

“The Writing Process” by Kathy Boylan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Prewriting Strategies” by Excelsior OWL is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Crafting Coherent Essays: An Academic Writer’s Handbook” by Erik Wilbur, John Hansen, and Beau Rogers at Mohave Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“The Writing Process” by Sarah Lacy and Melanie Gagich is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0