Chapter 5: Structuring

Why Engage in Structuring?

Once students complete the prewriting stage of the writing process, they often feel they are ready to write the draft of the essay. However, they are skipping an important stage of writing called structuring. The structuring stage includes identifying the main ideas you are going to develop, often called discussion points, and crafting a working thesis statement along with a detailed outline of the essay.

What Is a Thesis

A thesis statement is a sentence or a series of sentences that provides a map of your essay, explaining to the reader what debatable arguments about the topic you are going to make and in what order, foreshadowing the organization of your essay.

Your thesis statement is arguably the most important sentence in your essay, so it will take multiple revisions and adjustments to create the final version of it that will appear in your essay. It is helpful to start by creating a working thesis that will give you a plan for moving forward, but that will continue to change as you write your essay.

From Topic to Research Question to Working Thesis

In the prewriting stage, you have come up with a great topic, but to get from a topic to the working thesis, you should try to phrase your topic as a research question and then attempt to answer it.

For example, you may be interested in writing about college – specifically beginning college. Through the process of inquiry and prewriting, you might have narrowed down your broad topic to a few more specific research questions, such as:

What are the differences between college and high school? Or

What are the steps one has to follow to start college? Or

What is it like to return to college after years in the workforce?

Once you have a focused research question, you will try to answer it by developing supporting points (or discussion points), many of which you may already have at the ready from the prewriting stage. A detailed answer to your research question will become your working thesis statement.

Example 1: Topic – Research Question – Working Thesis

Research Question: What are the differences between college and high school?

Discussion Points:

|

College |

High School |

|

|

Working Thesis: College and high school are very different; specifically, college requires more time management skills, personal responsibility, and a strict budget.

Example 2: Topic – Research Question – Working Thesis

Research Question: Why do so many college students struggle with mental health, and how does it affect them?

Discussion Points:

|

Causes – Why do so many college students struggle with mental health? |

Effects – What happens as a result? |

| The lack of sleep contributes to students’ poor mental health. | Poor mental health leads to poor academic performance. |

| High levels of stress contribute to students’ poor mental health. | Poor mental health contributes to the high rate of college drop-outs. |

| Lack of counseling services on campus contributes to poor mental health. | Poor mental health can even lead to suicide. |

Working Thesis: The lack of sleep, high levels of stress, and lack of counseling services contribute to students’ poor mental health which can lead to poor academic performance, high rate of college dropouts, and even suicide.

or

Working Thesis: The lack of sleep and high levels of stress contribute to students’ poor mental health which can lead to poor academic performance.

Drafting a Working Thesis

Angle/Opinion and Discussion Points

As you develop your ideas into a map of your project, it is important to remember some basic guidelines about what makes an effective thesis statement. A thesis statement should be specific and present a claim, argument, or debatable point. A thesis is NOT the same as a topic; instead, the thesis expresses the writer’s belief or opinion about a topic. The thesis of an essay is the main point that the essay tries to prove, the central idea to which everything else in the essay is related. A thesis often is called a controlling idea (or main idea) because everything written in the essay is background or support for that idea. The thesis statement, therefore, is the most important component of the entire essay.

A basic thesis sentence has two main parts:

- Topic: What the essay is about.

- Angle/Opinion: The writer’s main idea or claim about the topic.

Examples of Thesis Statements: Topic + Angle/Opinion

Thesis: A regular exercise regime leads to multiple benefits, both physical and emotional.

The topic for this thesis is a regular exercise regime and the angle/opinion is that it leads to many benefits.

Thesis: Adult college students have different experiences than typical, younger college students.

The topic of this thesis is adult college students, and the angle/opinion is that they have different experience compared to younger students.

Thesis: The economics of television have made the viewing experience challenging for many viewers because shows are not offered regularly, similar programming occurs at the same time, and commercials are rampant.

The topic of this thesis is television viewing, and the angle/opinion is that it’s challenging for viewers due to the listed characteristics.

When you read all of the thesis statements above, can you see areas where the writer could be more specific with their angle? Specific thesis statements tend to create stronger essays because the more specific you are with your topic and your claims, the more focused your essay will be for your reader.

“List” vs. “Umbrella” Thesis

To help you understand the different levels of specificity in a thesis, let’s review two general concepts: “list” thesis vs. “umbrella” thesis.

A list thesis names the specific discussion points that will be covered in your essay while an umbrella thesis still provides the controlling idea/angle without naming specifics.

Examples

- List thesis: Federal funding for college students needs to be more accessible to low-income students, available at lower interest rates, and more transparent in order to avoid a nation of graduates owing millions of dollars once they graduate.

- Umbrella thesis: Federal funding for college students needs to be remedied quickly and efficiently in order to avoid a nation of graduates owing millions of dollars once they graduate.

A list thesis is taught to students when they are first learning how to create an essay. This method requires students to identify their topic and three or more main discussion points in their thesis; then, students are instructed to start each body paragraph with one of those main ideas. This is an effective method for creating a thesis if you only have a few supporting points; however, if you expect to have more than three supporting points, consider using the umbrella thesis.

An umbrella thesis has the advantage of providing an overall opinion on an issue that doesn’t specify your reasons for taking that position. This is a concise and coherent method for communicating your thesis. You are giving your angle/opinion on the issue (topic) and then giving your supporting opinions in the body of the essay.

Examples of “List” and “Umbrella” Thesis Statements

|

“List” Thesis Statements

|

“Umbrella” Thesis Statements

|

|

Americans should reduce their fast food intake because consuming too much fast food may lead to physical and mental health problems.

|

Veteran homelessness is a shameful problem in the United States; the government must provide better care for American heroes.

|

|

There are three simple steps to combating climate change: reduce, recycle, reuse.

|

LeBron James is a better basketball player than Kobe Bryant.

|

|

Lady Gaga may be a controversial performer, but she is a talented writer, singer, and dancer.

|

The United States should implement a guest worker program as a way of reforming the illegal immigration problem.

|

| This advertisement uses fear, humor, and anger to tempt consumers into purchasing their products. |

This advertisement uses an emotional appeal to tempt consumers into purchasing products that ensure happiness.

|

| Taking martial arts classes can help students gain confidence, build strength, and develop coordination. |

Nuclear power should be considered as part of a program to reduce our country’s dependence on foreign oil.

|

Qualities of Ineffective and Effective Thesis Statements

No matter what type of thesis you create, there are a few general guidelines that you should always follow.

|

An ineffective thesis contains or does the following:

Description Summary Unsupported Opinion Broad Obvious Vague Avoids debate Fact Question

|

|

An effective thesis contains or does the following:

Evaluation Selective Supported Opinion Narrow Not self-evident Specific Invites debate Insightful Assertion

|

Examples

|

Ineffective Thesis Statements |

Effective Thesis Statements |

|

Coffee is great. |

Patronizing Neighborhood Coffee Shoppe is more socially conscious than buying from Starbucks because its invasive business practices are harmful to local economies. |

|

Facebook is a social networking site that I use a lot. |

Facebook encourages superficial relationships that detract from the user’s relationships with people in their life. |

|

Malcolm Gladwell claims … |

Gladwell’s claim fails because… |

|

Religion and science are at odds. |

In his novel, Life of Pi, Yann Martel reconciles the competing notions of faith and science through allegory and constructs a symbiotic relationship between these two normally opposing ideologies. |

The ineffective examples are not adequate because they are unsupported opinions, descriptive, summary, broad, obvious, and don’t invite conversation or support. Maybe you don’t like coffee, or you don’t use Facebook. You could simply disagree. If so, you might say, “Well, I think coffee is disgusting,” or “I don’t use Facebook.” Not really engrossing conversation, right?

The effective examples succeed because they are evaluative, selective, and pose an assertion. A natural reaction to these would be, “why do you think that way?” Each prompts reactions that could lead to a more heated debate or at least an interesting exchange where each speaker refutes the other’s points or affirms their position with examples from their own life.

Remember, an effective thesis:

- Takes a stand

- Invites discussion rather than states a fact or summarizes the obvious

- Tells your audience what you want them to learn, think, act, or believe after reading your essay

- Helps the reader understand the organization of your essay: what points you are going to discuss and in what order.

Revising a Working Thesis

Remember that you can revise your working thesis at any stage of writing, and you may have various reasons to do that.

- You may discover that you cannot find any research to support one of the discussion points. It is OK to strike it from your thesis.

- While doing research, you may find another interesting discussion point. You should definitely include it in your thesis.

- You may realize that two discussion points in your thesis are too similar. You may combine those two points into one and discuss it in just one body paragraph to avoid repetition.

- You may come up with better phrasing for one of your discussion points or make revisions to the sentence structure to make your thesis more reader-friendly and clear.

Step One: Reduce Vagueness

You can pinpoint and replace all nonspecific words, such as people, everything, society, or life, with more precise words to reduce any vagueness.

|

Working Thesis |

Revised Thesis |

Revision Explanation |

|

Young people have to work hard to succeed in life. |

Recent college graduates must have discipline and persistence to find and maintain a stable job in which they can use and be appreciated for their talents. |

The original includes too broad a range of people and does not define exactly what success entails. By replacing those general words like people and work hard, the writer can better focus her/their/his research and gain more direction in her/their/his writing. The revised thesis makes a more-specific statement about success and what it means to work hard. |

Step Two: Clarify Ideas

Clarify ideas that need explanation by asking yourself questions that narrow your thesis.

|

Working Thesis |

Revised Thesis |

Revision Explanation |

|

The welfare system is a joke. |

The welfare system keeps a socioeconomic class from gaining employment by alluring members of that class with unearned income, instead of programs to improve their education and skill sets. |

A joke means many things to many people. Readers bring all sorts of backgrounds and perspectives to the reading process and would need clarification for a word so vague. This expression may also be too informal for the selected audience. By asking questions, the writer can devise a more precise and appropriate explanation for joke and more accurately defines her/their/his stance, which will better guide the writing of the essay. |

Step Three: Replace Linking Verbs with Action Verbs

Linking verbs are forms of the verb to be, a verb that simply states that a situation exists. Examples of linking (to be) verbs: Are, Am, Is, Was, Were.

|

Working Thesis |

Revised Thesis |

Revision Explanation |

|

Kansas City schoolteachers are not paid enough. |

The Kansas City legislature cannot afford to pay its educators, resulting in job cuts and resignations in a district that sorely needs highly qualified and dedicated teachers. |

The linking verb in this working thesis statement is the word are. Linking verbs often make thesis statements weak because they do not express action. Rather, they connect words and phrases to the second half of the sentence. Readers might wonder, “Why are they not paid enough?” But this statement does not compel them to ask many more questions. Asking questions will help you replace the linking verb with an action verb, thus forming a stronger thesis statement that takes a more definitive stance on the issue:

|

Step Four: Omit General Claims

General claims–like Instagram use is bad for teenagers–are hard to support. Revising your thesis to avoid general claims and contain only specific, supportable claims is preferable.

|

Working Thesis |

Revised Thesis |

Revision Explanation |

|

Today’s teenage girls are too sexualized. |

Teenage girls who are captivated by the sexual images on MTV are conditioned to believe that a woman’s worth depends on her sensuality, a feeling that harms their self-esteem and behavior. |

It is true that some young women in today’s society are more sexualized than in the past, but that is not true for all girls. Many girls have strict parents, dress appropriately, and do not engage in sexual activity while in middle school and high school. The writer of this thesis should ask the following questions:

|

Even though revising your working thesis statement may mean making additional adjustments in the body of the essay, your extra effort will usually pay off as your argument will become clearer and more persuasive. Your readers will surely appreciate it.

Exercise 5.1 Thesis Statement Practice

Part 1: Assume you have brainstormed about the subject “television” and have come up with the general topic, “The Quality of Television Commercials.” The asterisk (*) indicates the best thesis statement among the three examples. Explain why using the lists of Qualities of a Thesis included in The Working Thesis section.

a. I am going to explain why many televisions commercials are disturbing.

b. I strongly believe that many television commercials disturbing because they are boring, insulting, or dangerous.

c. Many television commercials are disturbing because they are boring, insulting, or dangerous.*

Part 2: Now examine each pair of thesis statements below and determine which thesis (a or b) is the better of the two. Explain why. Then, using the better of the two, decide if the thesis statement is a list or umbrella thesis. Explain why.

1a. Children must be adequately cared for.

1b. Although everyone agrees that children must be adequately cared for, this country does not properly regulate daycare centers.

2a. Many people find writing essays boring, but exotic surroundings, good humor, a few writing techniques can turn tedium into–yes, fun!

2b. Many people find writing essays to be difficult yet rewarding because of the ability to communicate important ideas and truths, persuade others, and simply play with language.

3a. Floyd Jarnagin, my grandfather, is a man of courage and determination.

3b. Floyd Jarnagin is my maternal grandfather.

4a. Our school’s parking problems could be solved if the administration made several changes.

4b. Despite the administration’s promises, parking at Oak Park College continues to be an extremely divisive issue that could be resolved with several inexpensive changes.

5a. The rise of medical marijuana usage can be attributed to advances in medical research, state law amendments, and the lessening of social stigmas.

5b. It is acceptable to use medical marijuana now.

Exercise 5.2 Write a Thesis Statement

Form a small group. As a group, pick one of the following topics, brainstorm it, narrow it, and write out a thesis statement: High School versus College, Siblings, First Jobs, Video Games, Social Media Sites, Favorite Teachers, Bad Drivers, Sports Heroes, Belief, Comedy. Write a summary of your group’s brainstorm and share it here along with the thesis statement you craft together.

Exercise 5.3 Create Effective Thesis Statements

Create working thesis statements for the following topics using the formula:

TOPIC + ANGLE/OPINION = THESIS STATEMENT

Fake News

Drone Technology

Fast Food

Homework

Helicopter Parents

Then have a partner check your thesis statements to see if they pass the tests to be strong thesis statements.

When reviewing the first draft and its working thesis, ask the following:

- Is my thesis statement an opinion, and is it a complete thought? Beware of posing a question as your thesis statement. Your thesis should answer a question that the audience may have about your topic. Also, be sure that your thesis statement is a complete sentence rather than just a phrase stating your topic.

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it is possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement provable? Can I establish the validity of it through the evidence and explanation that I offer in my essay?

- Is my thesis statement specific? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: Why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is, “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

For more practical tips on how to write thesis statements, please consult the following sources:

Outline

Now that you’ve narrowed down your topic and created your thesis, it’s time to start writing, right? Instead of jumping right in…pause for a few moments before beginning to amass your information into a first draft. Create an outline that begins with your thesis (or message). Include the subtopics as key elements. Under each subtopic, list your supporting points you have researched as well as the ideas you plan to add.

Creating an outline might seem like an unnecessary step. However, outlines ensure that your argument is well-organized and stays on topic. In addition, a well-thought-out outline can save hours of writing time. After all, it’s much easier to re-organize an outline than to re-write an entire essay!

There are two basic forms of outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline.

Topic Outline

An informal outline lists the parts of a paper without a specific structure. An author might use bullet points, letters, numbers, or any combination of these things. If your thesis statement clearly lists the discussion points you are going to address, creating an outline will be easy. Remember the concept of your thesis being the map of your essay? Each discussion point in your thesis will eventually become a body paragraph.

In the following example, you can see how each discussion point in the thesis statement will become a body paragraph in the essay:

Example of Topic Outline

Thesis: (1) The lack of sleep and (2) high levels of stress contribute to students’ poor mental health which can lead to (3) poor academic performance. CAC should educate students about mental health through (4) the college website, (5) workshops and (6) community forums.

Each numbered point will turn into a body paragraph. The reader knows exactly what points you are going to address and in what order.

Body paragraph 1 – lack of sleep

Body paragraph 2 – high levels of stress

Body paragraph 3 – poor academic performance

Body paragraph 4 – solution: educate students through the website

Body paragraph 5 – solution: educate students through workshops

Body paragraph 6 – solution: educate students through community forums

Sentence Outline

A sentence outline takes a regular outline to another step. In this type of outline, each and every single line should be a complete sentence. Instead of using a short phrase or word, you should have full sentences. It is more difficult, but at the same time, using complete sentences will help you clarify your ideas and organize your thoughts.

Example of Sentence Outline

Thesis: (1) Easy access to a wide variety of technological devices may lead to (2) addiction among teens and has a (3) negative influence on social skills.

I. Teens have easy access to a wide variety of technological devices.

A. Over the years, the advancements in technology made many devices cheap and accessible.

1. Smart phones are inexpensive.

2. Popular apps are free.

B. Teens are constantly using these technologies.

1. Many teens own smart phones.

2. Many teens spend countless hours on these devices.

II. Teens’ use of technology can be classified as addiction

A. The way teens use technology is often inappropriate.

1. Teens use devices while at school, which hurts their grades.

2. Teens text and drive even though they know it is dangerous.

3. Teens are unable to put away their devices even at night, which leads to poor sleeping habits

B. Scientists compared the relationship between teens and their devices to drug addicts and drugs.

1. The processes that happen in the brain of teens and drug addicts are similar.

III. Teens’ social skills are suffering.

A. Teens prefer to communicate online vs. face to face.

B. Teens are losing skills necessary in face-to-face interactions.

1. Teens can no longer interpret body language.

2. Teens are unable to interpret the tone of the conversation.

A hint about outlining: Regardless of which outline form you use, it is a good idea to write down all the headings/sentences for the first level of organization (i.e., the Roman numerals) before going on to the next level (i.e., the capital letters and all the capital letter headings). Doing so helps keep the levels of development, the subtopics, and details, clear.

When you are finished, evaluate your outline by asking questions such as the following:

- Do I want to tweak my planned thesis based on the information I have found?

- Do all of my planned subtopics still seem reasonable?

- Did I find an unexpected subtopic that I want to add?

- In what order do I want to present my subtopics?

- Are my supporting points in the best possible order?

- Do I have enough support for each of my main subtopics? Will the support I have convince readers of my points?

- Do I have ample materials for the required length of the paper? If not, what angle do I want to enhance?

- Have I gathered too much information for a paper of this length? And if so, what should I get rid of?

- Did I include information in my notes that really doesn’t belong and needs to be eliminated? (If so, cut it out and place it in a discard file rather than deleting it. That way, it is still available if you change your mind once you start drafting.)

- Are my planned quotations still good choices?

Traditional Essay Outline

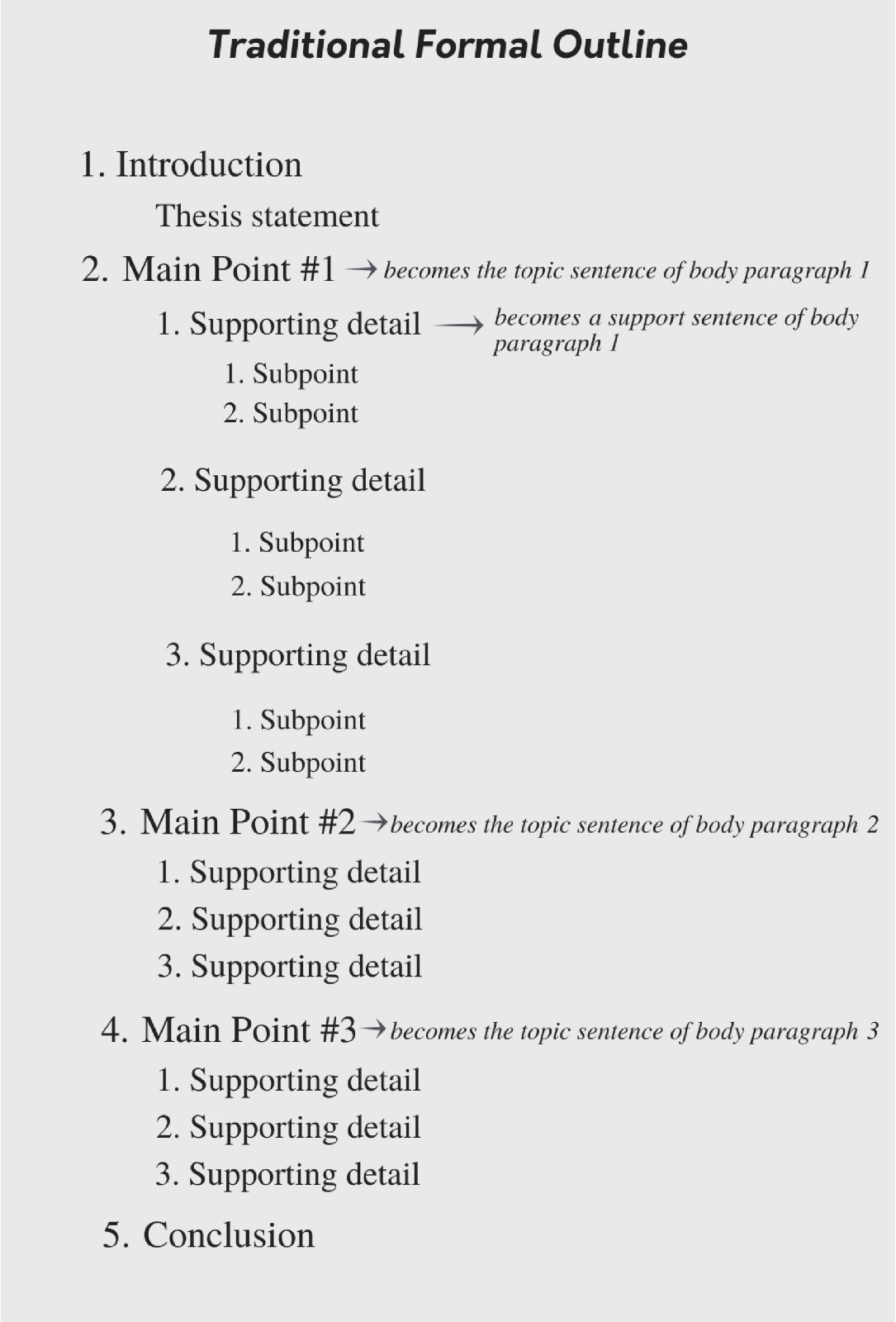

You are probably familiar with the traditional five-paragraph essay structure, and the outline for it looks something like this:

Figure 5.1 Traditional Formal Outline

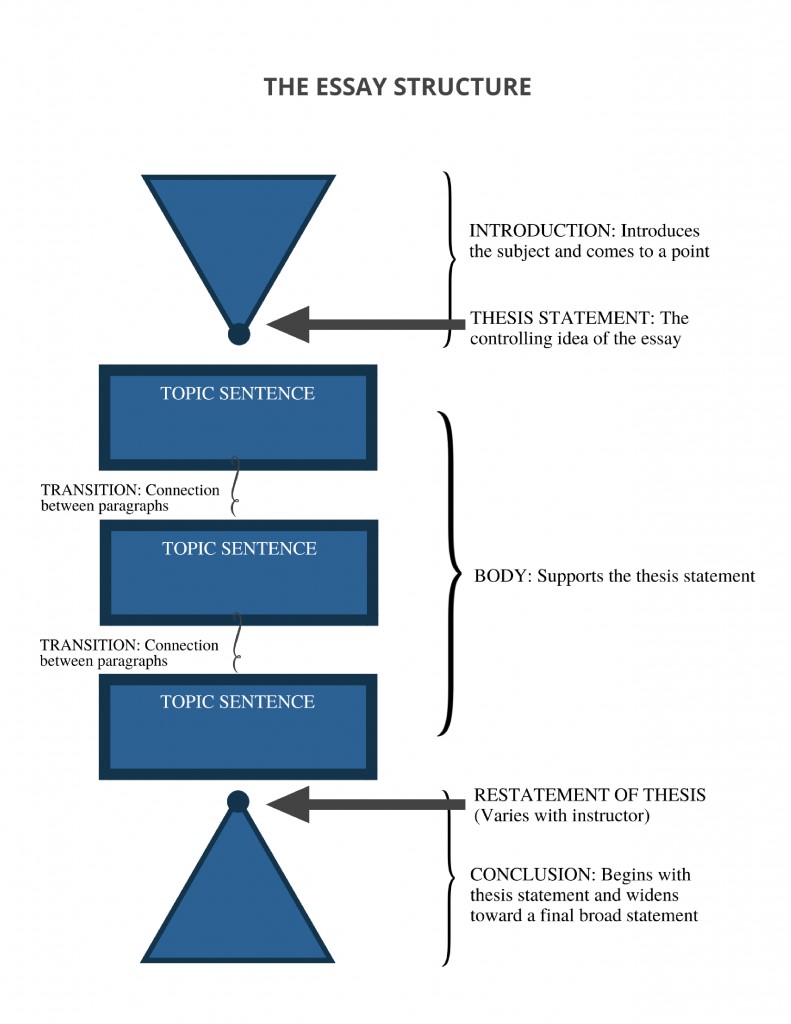

Review of the Five-Paragraph Format

Many writers will be able to detail the five-paragraph format.

- The introduction previews the entire essay.

- The thesis statement goes at the end of the introduction and describes what the three body paragraphs will be about.

- The body paragraphs discuss each topic described in the thesis statement in detail.

- There should be transitions between each body paragraph.

- The conclusion repeats key points made in the essay and could be the introduction re-worded in a different way.

Figure 5.2 The Essay Structure

Problems with the Five-Paragraph Format

Donald Murray in his article “Teach Writing as a Process Not a Product” argues writing should be taught as “…the process of discovery through language. It is the process of exploration of what we know and what we feel about what we know through language. It is the process of using language to learn about our world, to evaluate what we learn about our world, to communicate what we learn about our world” (4). However, when writers use writing to discover more about a topic, the five-paragraph format can be limiting because of the following:

- Writers usually decide on the three main body paragraphs before they start drafting.

- With three large topics to change from, writers are less likely to dig deep into a specific topic.

- Writers may use the five-paragraph format in ways that avoid detail and make their essays indistinguishable from other essays on the same topics.

For instance, a writer might want to discuss communication on social media. They decide before they start writing that their three main topics will be Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. By the time they write a few details about Facebook, they move on to Instagram. There is not enough space for the writer to get into details and differentiate ideas on their topic and to describe observations, experiences, and research in depth. When writers start with three main topics, it’s also hard to find the space to teach the reader something new.

Writing is an opportunity to share unique experiences with readers. If writers feel like they are not sharing anything valuable through their writing, they should reconsider their stance on the assignment or schedule a meeting with their instructor so that they can orient themselves more meaningfully to the assignment. Often, five-paragraph format writing is uninspired. Writers race to jot down what they know on three loosely related subjects so that they can finish the essay. The writer is not learning through the writing and neither is the reader. The main problem with the five-paragraph format is that it discourages writers from discovering what they could write on one focused and specific topic.

When to Use the Five-Paragraph Format

Published essays, in any genre, that use the five-paragraph organization are very rare. It might be interesting for writers to pay attention to how published material that they read on their own time is organized. Because first-year writing is a context where writers are encouraged to learn and teach through their writing, the five-paragraph format might not be the best choice for organization. However, when writers are in situations that demand them to relay information quickly, the five-paragraph format can be useful. Formulaic writing is not uninventive or inherently bad. Different genres use various kinds of formulaic writing, and it’s important for writers to adhere to conventions and pay attention to how essays are organized in the genre they are writing in.

Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Format

How to get started writing without the five-paragraph format

If writers are not going to use the five-paragraph format, then how should they get started with the writing process? While it might seem logical to start writing the essay with the introduction, there are downsides to starting with the introduction if the writer has not already done extensive thinking or planning for the essay:

- The writer does not know exactly what the essay is about yet, so they might have to rewrite the introduction to match what they end up writing.

- The writer may end up writing multiple introductions while trying to find a way to summarize and introduce a topic they have not yet written on.

- The writer may feel stuck and experience writer’s block.

- Freewrite

- Write the body of the essay

- Make a working outline

- Create a list of what they want to include

- Follow the steps of the writing process.

Different kinds of organizational patterns for writers include chronological, general to specific, specific to general, climactic, problem-solution, and spatial. The following sections detail these techniques. Writers often use multiple kinds of organization within one essay, using one technique for one paragraph, one technique for another paragraph, multiple techniques in a single paragraph, and a technique for the overall organization and flow of the essay.

Chronological

Writers who use chronological organization for their essay write about events that took place first in the beginning of the essay and then move to events that occurred later, following the order in which the events took place. Chronological order could be interesting for writers to purposefully play around with in their writing. Could the writer start at the end or the middle of the event to draw the reader in or make their structure more interesting? Writers might use chronological for sections of their essay in which they detail events that have already taken place or to describe historical events relevant to their topic.

Example of Chronological Organization

If a writer wants to describe how they learned German, they can start with the first time that they heard the language, then describe (in the order which they occurred) the events and significant moments in their journey of learning the language.

General to specific

With general to specific organization, the writer starts with a broad perspective and then moves in more closely to their subject. This organization meets imagined readers at a level of specificity that they can easily connect with. The writer then gets more detailed, bringing the reader with them, and zooming in on the specific topic they are describing.

Example of General to Specific Organization

If a writer wants to describe how students at CAC use Blackboard to communicate (and they want to reach a wider audience than college students and instructors), they could begin by describing the broader topic of how college courses use online technologies, then the writer can get more specific into the details of Blackboard as they write more.

Specific to general

When using specific to general organization, the writer starts with details of their topic and then moves the focus to a broader context as they continue to write.

- Writers can start with their findings or their main point and then work backwards, describing how the more specific points fit into a larger context.

- Writers can start with very minute details of the situation they want to describe. Readers may not know exactly what the writer is describing, but as they continue reading, the writer reveals the context by zooming out more.

Example of Specific to General Organization

If a writer wants to describe communication in soccer, they could begin by describing an exciting minute of gameplay and how players communicate with each other during those intense moments. The writer might want to include jargon to make the situation realistic. Then, as the writer moves further away from the details, they can describe the jargon for the reader and contextualize the communication by putting it in the broader context of the soccer game and soccer culture.

Problem-solution

In problem-solution format, writers describe a problem and then describe the solution to the problem. Not every essay topic can utilize problem-solution organization because there might not be a problem or a solution involved with the topic.

Example of Problem-Solution Organization

If a writer wants to discuss health literacy and why it’s important, they could start by describing problems that might occur if adults do not have health literacy, then they could describe how health literacy could be improved.

Spatial

In spatial organization, writers describe their subject based on its location in space with other objects. To use this technique, writers could identify a concrete space to describe. Writers could also imagine their topic and how it relates to geography, describing relevant events in an order that progresses from east to west or north to south, depending on their purpose.

Examples of Spatial Organization

Example 1

If a writer is describing the impact of social media, they could include a spatial description of the screen a user sees on Instagram. What appears on the screen as users scroll through the app they are investigating? What’s on the top and bottom of the screen? What about from the left to the right of the screen?

Example 2

If the writer is discussing a workplace, they could start from one corner of the workstation and move systematically through the space describing each part and section making sure to use details to bring the location to the reader.

Climactic

Most writers will be familiar with movies, video games, novels, or plays being climactic. Climactic plots have the most action-filled scenes, major twists, or character deaths towards the end, around 75-90% of the way through the plot. Climactic college writing can vary widely. In climactic organization, the thesis statement will most likely not be at the end of the introduction but towards the end of the essay. According to Thelin, if the writer has a controversial stance, it might be best to save their conclusion towards the end (95). Saving a controversial finding until the end of the essay gives the writer time to get the reader feeling and understanding the topic like they do. However, topics don’t need to be controversial for writers to use climactic organization.

Example of Climactic Organization

If a writer wants to discuss how social media is addictive, they could save their findings until they are almost finished with their essay. The beginning of the essay could include descriptions, observations, and research. Then, after the writer has drawn a clear picture of social media for the reader, they can reveal their finding that social media may be addictive.

For more tips on how to create effective outlines, watch the following video:

After completing the structuring stage of writing, you now have a working thesis with distinct discussion points and a detailed outline that serves as a map to the rest of your essay. Remember that you may continue to make changes to your thesis and your outline as you move to the next stage of writing – drafting.

Key Takeaways

- A thesis statement is a sentence or a series of sentences that provides a map of your essay,

- A thesis is NOT the same as a topic; instead, the thesis expresses the writer’s belief or opinion about a topic. The thesis of an essay is the main point that the essay tries to prove, the central idea to which everything else in the essay is related.

- An outline creates structure for your argument. You can use topic or sentence outline formats.

- The five-paragraph essay can be useful for formulaic writing. However there are many other formats that can be useful.

- Chronological, general to specific, specific to general, climactic, problem-solution, and spatial are different organizational patterns.

Attributions

“Crafting Coherent Essays: An Academic Writer’s Handbook” by Erik Wilbur, John Hansen, and Beau Rogers at Mohave Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“The Writing Process” by Kathy Boylan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“The Roughwriter’s Guide” by Karen Palmer and Sandi Van Lieu is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“A review of the five-paragraph essay” by Julie Townsend is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Moving Beyond the five-paragraph format”by Julie Townsend is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Image Credits

Figure 5.1: The Writing Process by Kathy Boylan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0