Chapter 15: Critical Evaluation and Ethical Use of Sources

Media Literacy, Emerging Technologies, Academic Integrity, and Plagiarism

How Do We Know Who To Trust?

You are here and able to read this chapter because your earliest ancestors developed the knack for being able to detect when someone was lying to them. They were able to recognize when something felt off about the person they were speaking to. What was it? Maybe it was the way the smile on a speaker’s face did not seem to reach their eyes. A real smile moves many muscles in the face, while a false smile tends to only move the lips. Maybe it was the way they spoke so smoothly—too smoothly—as if what they were saying was rehearsed rather than spontaneous. Whatever the reasons, your ancestors recognized the potential dangers this person posed and thus were more likely to avoid a possible threat to their safety and survive long enough to pass on their genes to their descendants. And here you are: the product of people who were smart enough to know when they were being lied to because your ancestors knew how to read body language and were able to pick up on the numerous physical and verbal clues of someone who should not be trusted.

But how do we know if someone is lying to us when all we have are words on a page with no other clues to go by? For hundreds of years printed material evolved in ways to answer this question. There were publishing houses who earned the trust of readers because they employed many people to do things like fact-checking, editing, proof-reading, etc.

But how do we know if someone is lying to us when all we have are words on a page with no other clues to go by? For hundreds of years printed material evolved in ways to answer this question. There were publishing houses who earned the trust of readers because they employed many people to do things like fact-checking, editing, proof-reading, etc.

Digital media is different. There need not be gatekeepers between a content-creator and an audience. The good news is that anyone can now publish, allowing us access to vast amounts of raw data, knowledge that is both wide and deep, and varying perspectives that would have never seen the light of day if not for digital forms of media. We have more information available to us than at any previous time in human history.

The bad news is…anyone can now publish, and it can be difficult to know whether or not a source is reliable. How do we know if the author of a website really has a Ph.D. on the subject they are discussing? How do we know if the photograph we see was manipulated to deceive our eyes? How can we know if the video we are watching has been run through an artificial intelligence algorithm to make it look and sound as if an individual is saying something that they have never uttered?

This chapter is designed to give you some tools to help you navigate the rapidly changing environment in which reading, writing, and research now take place. It is broken up into five sections: (1) general guidelines, (2) photo-shopping and deepfakes, (3) artificial intelligence, (4) plagiarism, and (5) AI and plagiarism.

There is nothing wrong with trust. Trust is a good thing—but make sure that those in whom you place your trust are truly worthy of what you are giving them.

General Guidelines for Determining the Credibility of a Source

Berkeley Method

Below are questions from the University of California Berkley Library that will enable you to take a step-by-step approach when it comes evaluating sources.

When you encounter any kind of source, consider:

- Authority – Who is the author? What is their point of view?

- Purpose – Why was the source created? Who is the intended audience?

- Publication & format - Where was it published? In what medium?

- Relevance - How is it relevant to your research? What is its scope?

- Date of publication - When was it written? Has it been updated?

- Documentation – Did they cite their sources? Who did they cite?

Authority

- Who is the author?

- What else has the author written?

- In which communities and contexts does the author have expertise?

- Does the author represent a particular set of world views?

- Do they represent specific gender, sexual, racial, political, social and/or cultural orientations?

- Do they privilege some sources of authority over others?

- Do they have a formal role in a particular institution (e.g. a professor at Oxford)?

- Why was this source created?

- Does it have an economic value for the author or publisher?

- Is it an educational resource? Persuasive?

- What (research) questions does it attempt to answer?

- Does it strive to be objective?

- Does it fill any other personal, professional, or societal needs?

- Who is the intended audience?

-

- Is it for scholars?

- Is it for a general audience?

-

Publication and Format

- Where was it published?

- Was it published in a scholarly publication, such as an academic journal?

- Who was the publisher? Was it a university press?

- Was it formally peer-reviewed?

- Does the publication have a particular editorial position?

-

- Is it generally thought to be a conservative or progressive outlet?

- Is the publication sponsored by any other companies or organizations? Do the sponsors have particular biases?

-

- Were there any apparent barriers to publication?

- Was it self-published?

- Were there outside editors or reviewers?

- Where, geographically, was it originally published, and in what language?

- In what medium?

- Was it published online or in print? Both?

- Is it a blog post? A YouTube video? A TV episode? An article from a print magazine?

- What does the medium tell you about the intended audience?

- What does the medium tell you about the purpose of the piece?

Relevance

- How is it relevant to your research?

- Does it analyze the primary sources that you’re researching?

- Does it cover the authors or individuals that you’re researching, but different primary texts?

- Can you apply the authors’ frameworks of analysis to your own research?

- What is the scope of coverage?

- Is it a general overview or an in-depth analysis?

- Does the scope match your own information needs?

- Is the time period and geographic region relevant to your research?

Date of Publication

- When was the source first published?

- What version or edition of the source are you consulting?

- Are there differences in editions, such as new introductions or footnotes?

- If the publication is online, when was it last updated?

- What has changed in your field of study since the publication date?

- Are there any published reviews, responses or rebuttals?

Documentation

- Did they cite their sources?

- If not, do you have any other means to verify the reliability of their claims?

- Who do they cite?

- Is the author affiliated with any of the authors they’re citing?

- Are the cited authors part of a particular academic movement or school of thought?

- Look closely at the quotations and paraphrases from other sources:

- Did they appropriately represent the context of their cited sources?

- Did they ignore any important elements from their cited sources?

- Are they cherry-picking facts to support their own arguments?

- Did they appropriately cite ideas that were not their own?

The C.R.A.A.P. TEST

Another way to evaluate the credibility of a source is through the CRAAP test. This method is not as in depth as the Berkley approach discussed above, but it is a good way to weed out sources that are not credible. If a source passes the CRAAP test, then you can move on to the Berkley method for a more comprehensive analysis of your source.

The CRAAP test looks at five features of a source:

- Currency: Determine if the date of publication of the information is suitable for your project.

- Relevance: Determine how applicable the information is to your project.

- Authority: Determine if the source author, creator, or publisher of the information is the most knowledgeable.

- Accuracy: Determine the reliability, truthfulness and correctness of the content.

- Purpose: Determine the reason why the information exists.

Below is a quick overview of these features:

C urrency – is it recent enough to be informative?

R elevance – does it relate to your research question?

A ccuracy – is the information truthful and correct?

A uthority – does the information come from a reliable source?

P urpose – why was the book/website written, and is it biased? Does it inform, persuade, entertain, or try to sell something?

Who – who wrote the material, and is he/she knowledgeable?

What – what is the reason for writing the material?

When – when was the information written? (For websites, has it been kept current?)

Where – where does the author get his/her information?

Why – why would I use this particular source?

How – how well is the source written or edited?

For a more detailed look on how to apply the CRAAP test, see the link below:

https://guides.library.illinoisstate.edu/evaluating/craap

And check out this video

Media Bias

Lastly, you can explore the many differing perspectives on an issue by using the Media Bias Chart to identify sources that are biased on any given issue. Media bias is discussed in more depth in Chapter 13 in “Evaluating Ethos” with definitions of political bias and publication bias.

The Media Bias Chart locates different news sources on a spectrum of reliability and bias. It’s important to understand that this can be subjective, but the group Ad Fontes has worked to develop an objective measure to determine reliability and bias in each source. It’s a great starting point for understanding the bias of different news sources. Understanding a subject from multiple viewpoints will not only strengthen your ability to determine if a source is credible, but it will also give you deeper insight into how various people can examine the same topic and come to entirely different conclusions.

You can visit the link below for a more interactive version of the Media Bias Chart.

The methods above will help you determine a source’s credibility and allow you to explore differing viewpoints from information sources. But the information landscape is changing and will continue to evolve as the pace of various technologies accelerate. To address these changes, we need to add a few more methods to our intellectual tool kit, ones that apply to more recent and emerging technologies.

There are many different types of bias. Check out this article from All Sides, “How to Spot 16 Types of Media Bias” for a list of different types of biases to look for in the media. Are any of these biases evident in the article or purblication?

Photo-shopping and Deepfakes

Photo-shopping

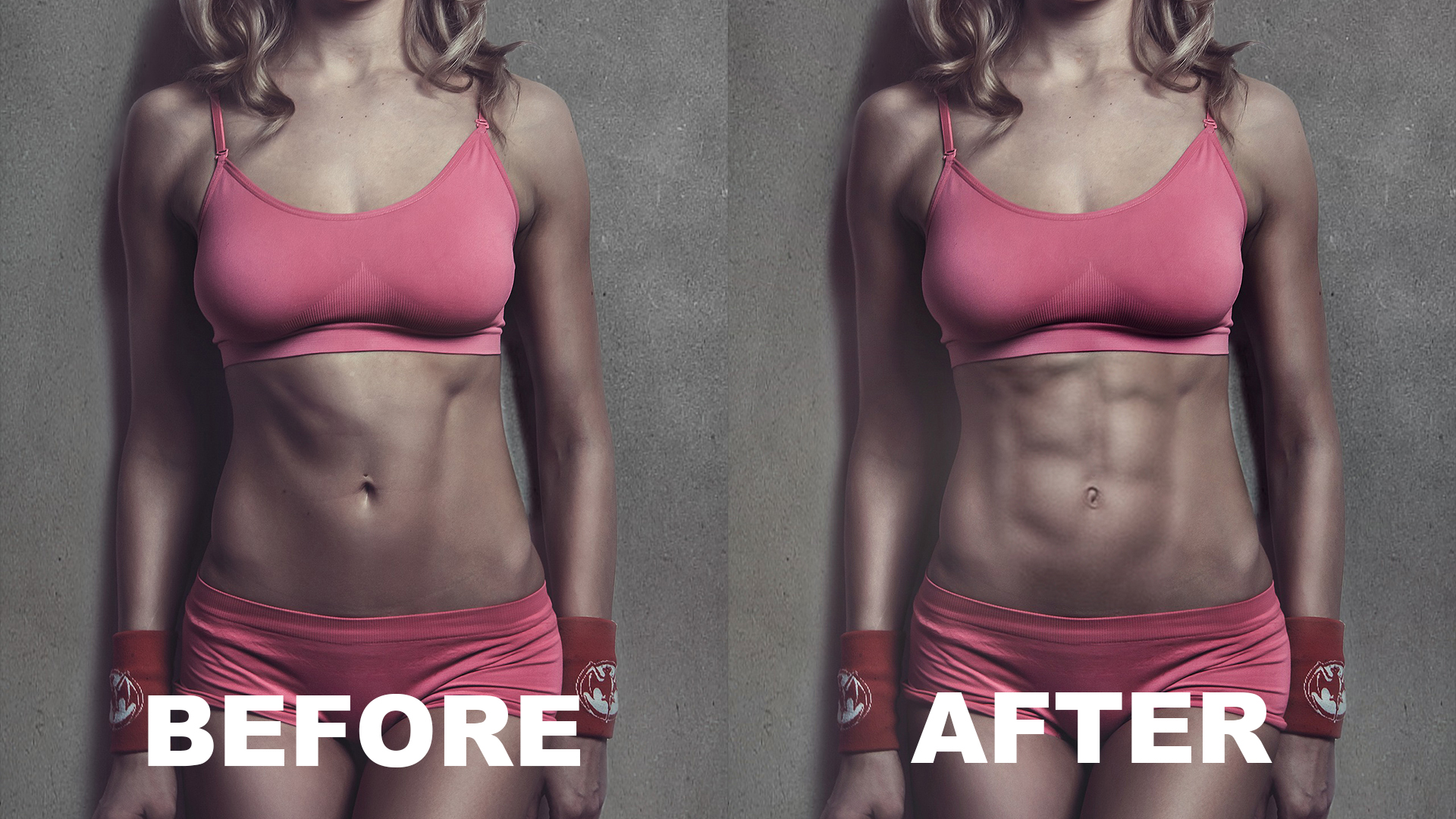

According to Merriam-Webster, photo-shopping is when a digital image is altered “with Photoshop software or other image-editing software…in a way that distorts reality (as for deliberately deceptive purposes).”

A People magazine article explained how a photograph of Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales, with her children had been digitally altered. Here is a brief list of what was found when examining the this photograph:

- Part of Princess Charlotte’s sleeve was removed above her left hand.

- The zipper on Princess Kate’s top appears edited.

- Princess Charlotte’s hair cuts off oddly.

- Princess Charlotte’s skirt appears to stick out in a strange way around her waist.

- Princess Charlotte’s knee seems blurred.

- The pattern on Prince Louis’ sweater sleeve is skewed.

- Prince Louis’ right thumb looks blurry.

- There is an indent in the ledge near Prince Louis’ hand.

- Another distortion is seen on the ledge.

- The step behind Prince Louis appears warped with the floor.

- Prince Louis’ finger seems cut off.

- The edge of Prince George’s blue sweater looks enhanced.

- Princess Kate’s hand is out of focus but the area around it is.

- Princess Kate’s hair appears airbrushed.

- Princess Charlotte’s hair appears tucked strangely.

- Prince George’s sweater sleeve has odd lines.

Example

According to TechTarget, a deepfake is “is a type of artificial intelligence used to create convincing images, audio, and video hoaxes.”

The article explains how deepfakes are created through artificial intelligence algorithms so that a video appears realistic. Remember that false smile our ancestors were able to detect because key muscles in the face did not move the same way they would if a smile was genuine? Deepfakes use artificial intelligence algorithms to manipulate the image of a person’s face so that the entire face behaves as if a smile is genuine while saying words that are false. It can also create facial muscle movements that almost exactly match words that have never been spoken by the person being depicted.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office suggests methods that can be used to detect deepfake videos, as well as important questions that this technology raises. As the site notes, “Deepfakes are powerful tools that can be used for exploitation and disinformation. Deepfakes could influence elections and erode trust….The underlying artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are widely available at low cost, and improvements are making deepfakes harder to detect.”

See this article for more examples “Deepfake AI-generated images that went viral in 2023”

Why does it matter?

Resistance against photo manipulation

In recent years, however, there has been public resistance against this practice in advertising and other media, calling for more realistic and natural portrayals of people. Thankfully, content creators are starting to embrace images that use more natural photo editing. But even with people protesting against it, photo manipulation will probably be around for a long time to come. That means you’ll need to keep an eye out for images that seem too good to be true.

More on Photo Manipulation

Key Takeaways

- Photo-shopping and deepfakes are both examples of photo manipulation.

-

These types of photo manipulation can affect our mental well-being by creating unrealistic expectations.

-

Photo manipulation can also alter our perception of reality, misleading the public in relation to events happening in our global and local communities. This can affect how we vote, what policies are put into place, and our perception of important issues.

-

Critical thinking is key to being an informed consumer and citizen.

Artificial Intelligence

According to McKinsey and Company, artificial intelligence is “a machine’s ability to perform …cognitive functions we usually associate with human minds.” The article “What is AI?” gives readers an overview of the history of AI (a concept introduced by Alan Turning in the 1950s that has roots in earlier ideas about robotics), an explanation of how artificial intelligence works (through a style of operation called “deep learning”), and the benefits and risks associated with this still-developing technology.

According to McKinsey and Company, artificial intelligence is “a machine’s ability to perform …cognitive functions we usually associate with human minds.” The article “What is AI?” gives readers an overview of the history of AI (a concept introduced by Alan Turning in the 1950s that has roots in earlier ideas about robotics), an explanation of how artificial intelligence works (through a style of operation called “deep learning”), and the benefits and risks associated with this still-developing technology.

For a strong overview on the ethics of using AI—as well as the many ethical questions that society is currently grappling with—see the article below from Cornell University.

While the use of artificial intelligence in research and writing leads to a number of fascinating—and, at times, unsettling—ethical questions, other ethical issues regarding research and writing are clearer and more easily understood, with criteria that has a long history. The issue of plagiarism may seem daunting at first, but once you know what it is and how to avoid it, you will be well on your way to using the sources you have analyzed thus far with integrity and confidence.

Plagiarism and Academic Integrity

Your own commitment to learning, as evidenced by your enrollment at CAC, and the Student Code of Conduct require you to be honest in all your academic course work. Each student is obligated to know the rules that preserve academic integrity and abide by them. This includes learning and following the rules associated with specific classes, exams, and/or course assignments. Ignorance of these rules is not a defense to the charge of violating the Student Code of Conduct Policy. CAC tracks incidents that violate the Academic Integrity policy.

The CAC Student Handbook contains the Student Code of Conduct. To access the handbook, click this link, scroll down and click the link for the most updated version of the handbook.

Definitions

The CAC Student Handbook defines cheating as “the use or attempted use of information, academic work, research or property of another as one’s own. Cheating includes, but is not limited to, plagiarism, sharing knowledge during an examination, or the willful disobedience of testing rules” (2). Additionally, CAC tracks incidents that violate the Academic Integrity policy.

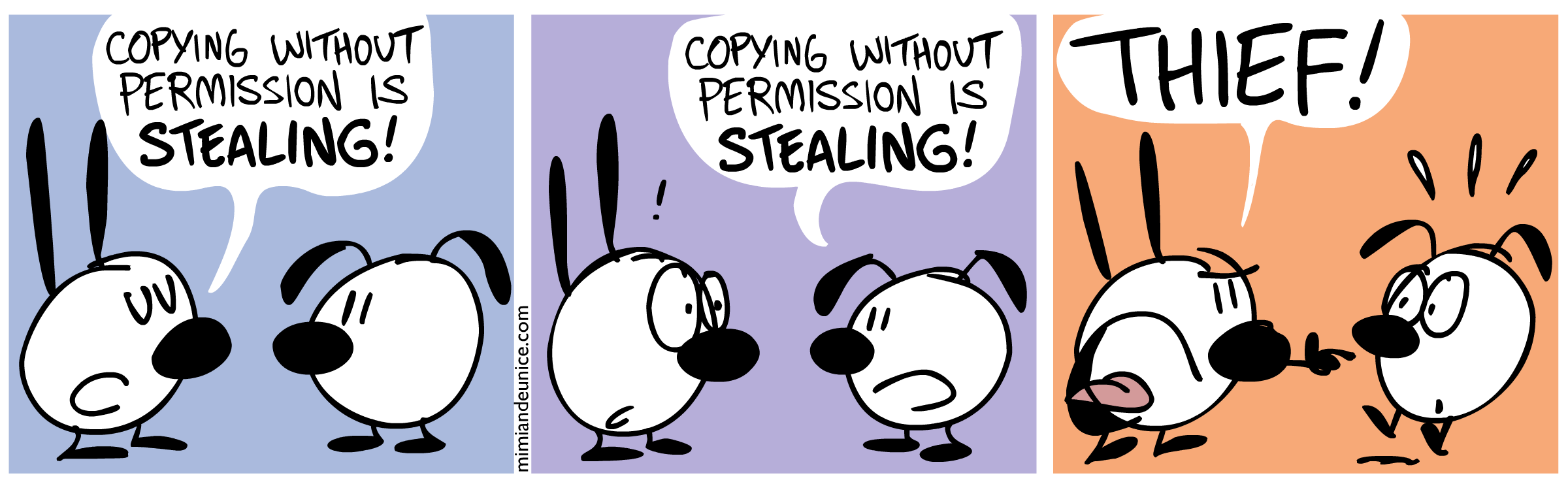

Plagiarism originates from the Latin word, plagiarius (‘kidnapper’). In an intellectual sense, plagiarism means the abduction of someone else’s words, ideas, or thoughts.

The Modern Language Association provides the following discussion on plagiarism in the MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition:

The Modern Language Association provides the following discussion on plagiarism in the MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition:

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines plagiarizing as committing “literary theft.” Plagiarism is presenting another person’s ideas, information, expressions, or entire work as one’s own. It is thus a kind of fraud: deceiving others to gain something of value. While plagiarism only sometimes has legal repercussions (e.g., when it involves copyright infringement—violating an author’s exclusive legal right to publication), it is always a serious moral and ethical offense. (MLA 6-7)

Simply put, plagiarism is the uncredited use (both intentional and unintentional) of the words, ideas, or thoughts of another.

Generally, there are two reasons individuals are tempted to commit plagiarism:

- Lack of confidence in own ideas, voice, and/or writing abilities.

- Lack of interest in a subject or writing task.

- Poor time management.

Types of Plagiarism

There are two types of plagiarism: intentional and unintentional.

Intentional plagiarism occurs when a writer intentionally uses the words or ideas of another without giving credit. Examples of this range from purchasing an essay off the Internet or from a fellow student and handing it in as original work to copying and pasting portions of a source into original work without giving credit. Intentional plagiarism also includes rewording the ideas and substance of a source and failing to attribute the original.

Unintentional plagiarism usually occurs because students are unsure how to incorporate others’ ideas into their own, do not know how to properly cite sources, or do not give themselves enough time with the research and writing process.

Examples of Intentional and Unintentional Plagiarism

|

Intentional |

Unintentional |

|

|

To maintain integrity, make intentional choices when you integrate sources into your writing, use attributions to indicate when you include the words, ideas, or thoughts of another, and properly cite those sources.

Strategies to Avoid Plagiarism

- Make your ideas the driving force behind your writing.

- Establish authorial voice.

- Keep detailed research notes and build an annotated bibliography as you research. Better to have a source and not need it than need a source and not have it.

- When in doubt, cite. You will not be penalized for citing. The same cannot be said for failing to cite.

- Use signal phrases.

- Utilize resources:

-

- This textbook.

-

- Your instructor.

It is your instructor’s responsibility to teach you why and how to integrate other voices into your conversations and guide you in developing skills of attribution and citation; the next section of this chapter is devoted to these skills too. It is your responsibility to maintain integrity by refraining from acts of intentional plagiarism and avoiding instances of unintentional plagiarism. Remember, your instructors do not expect your writing voice to sound like that of scholarly sources. They expect writing that is appropriate for the course level in which you are working. To maintain integrity, make intentional choices when you integrate sources into your writing, use attributions to indicate when you include the words, ideas, or thoughts of another, and properly cite those sources.

For ways to properly use sources in your writing, see Chapter 17 in this book.

Exercise 15.1

RESPOND TO QUESTIONS ABOUT PLAGIARISM

Your instructor may ask you to respond to the following questions in writing or as part of class discussion:

- Explain how to handle plagiarism: Discuss how colleges and universities should handle plagiarism in the age of the Internet. Offer some ideas about how professors can steer students away from the temptation to plagiarize.

- Brainstorm your ideas about intellectual property and plagiarism. Where do you stand, for example, on the issue of music file sharing? What about downloading movies free of charge? Do you think these forms of intellectual property should be protected under copyright law? How do you define your own intellectual property, and in what ways and under what conditions are you willing to share it? Finally, come up with your own definition of academic integrity.

- How do the concepts of plagiarism and academic integrity translate from the academic environment to the professional environment?

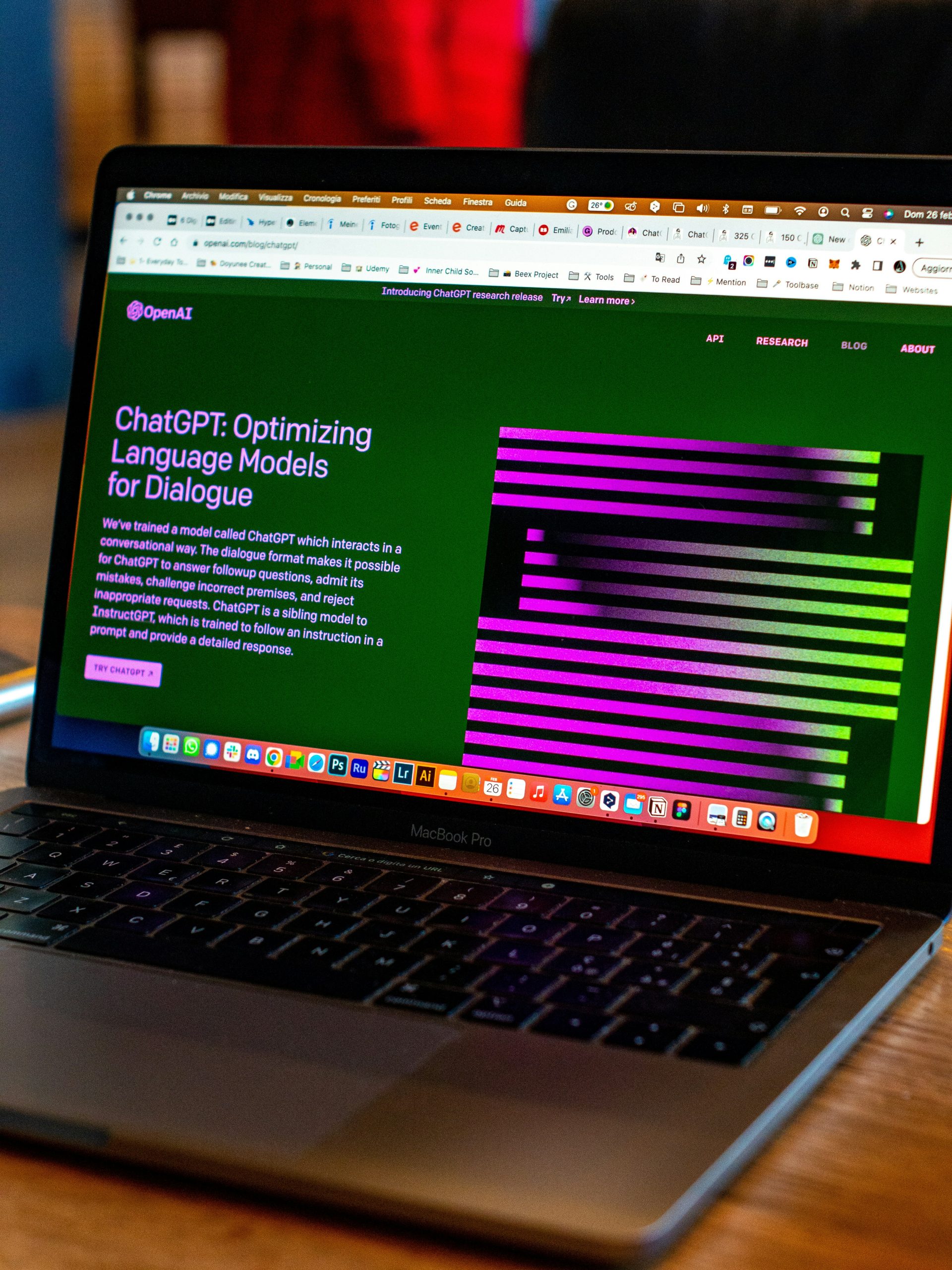

AI and Plagiarism

Artificial intelligence is everywhere these days–from chatbots and search engines, to audio and video tools. The world of writing, and student papers in particular, is no exception. While there may be legitimate uses for these tools—if you use ChatGPT or other AI/large language models to create written content for any of your classes, you could be guilty of plagiarizing.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are built upon massive databases of text scraped from sources like books and journals, but also blogs and social media sites. When you prompt an LLM with a question, the program draws upon its data to provide the most likely answer. Despite being described as “artificial intelligence”, these LLMs are not thinking—they are using statistical analysis to predict the most likely response. Essentially, LLMs work like the suggestions you see when typing out a text message.

As much of the data used to build LLMs was taken from original sources without attribution (or attention to copyright), some might argue that LLMs are themselves plagiarism machines. Regardless, content derived from LLMs cannot be considered truly original. Submitting work that is not your own is the very definition of plagiarism.

For guidance on what NOT to do within your courses, here is a list of things to avoid. (Note: This is subject to your instructor’s guidance! Some instructors are adapting and using AI as part of the learning experience, so always check with your instructor if you are unsure of what to do.)

- Do not use ChatGPT or other AI tools to produce responses to discussion prompts, essays, bibliographies, or any other written work you are asked to create for a class.

- Do not ask AI writing tools to edit your work for you. Doing so is akin to asking your writing tutor to fix all your mistakes. This is still cheating, and you should not do it.

- Avoid the temptation to ask LLMs to generate a list of sources for your paper on a particular topic. While it’s possible for an LLM to act as a jumping off point for further research/study, the tools are prone to hallucination—they will provide information that sounds correct but is entirely made up. While this is not technically plagiarism, using faulty information in your writing will certainly result in a bad grade.

Of course, completing assignments that specifically allow or require the use of AI would not be considered plagiarism. If you aren’t sure whether AI is allowed for an assignment, you should consult your instructor.

Remember that at many institutions, the punishment for plagiarism can be as severe as expulsion. Additionally, keep in mind that your instructors have likely read hundreds of thousands of words of student writing. AI-assisted writing will not be difficult for them to spot.

Ultimately, the only way to become a truly skilled writer is by writing, as much as you can and as often as you can. Furthermore, the purpose of academics is to engage with the material and draw your own conclusions. Don’t cheat yourself of the chance to become great by using a bot to think for you!

Conclusion

We covered quite a lot in this chapter, from the way our ancestors dealt with the issue of credibility to the challenges we will be facing as we approach the end of this decade. Thanks to the intelligence of your ancestors, you are a part of the history of source evaluation, and, as technology continues to transform how we read, write, and even think, you will undoubtedly be a part of its future.

Attributions

“Evaluating Sources” by University of California Berkeley Library is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Photographic Manipulation” on Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Photo Manipulation” by GCF Global is licensed under Terms of Service

AI and Plagiarism by Excelsior OWL is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image Credits

Black Haired Man Making a Face Photo by Ayo Ogunseinde on Unsplash

Reliable Sources by Samkille on Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

ChatGPT Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash

Person cheating on exam Photo by Andy Barbour at Pexels

Before – After – How to Get Fake Six Pack ABS Easily in Photoshop by PSDESIRE on Flickr is licensed under CC0 1.0