Chapter 2: The Rhetorical Situation

What is Rhetoric?

Rhetoric is communicating to persuade. Rhetoric can take place via media, speech, written texts, images, or any other mode of communication. Rhetoric is a key part of our lives: consider that when we demand a raise at work, argue about politics on social media, or text a friend to ask for a ride, we are engaging in acts of rhetoric. Understanding how to use rhetoric empowers us to make significant changes in our local and even global communities.

Figure 2.1 Rhetoric is everywhere

What Is the Rhetorical Situation?

The term “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstances that bring texts into existence. The concept emphasizes that communicating is a social activity, produced by people in particular situations for particular goals. It helps individuals understand that, because communicating via writing, images, or other modes is highly situated and responds to specific human needs in a particular time and place, texts should be produced and interpreted with these needs and contexts in mind.

Here is a list of possible communication situations for a college freshman:

- a text message to my friend or parent

- an email to a professor about my grade

- an Instagram post about my new college experience

- an essay for my English professor about current women’s rights issues

- a problem/solution essay for my environmental biology class about sustainable energy

- a scholarship application essay

- a slideshow presentation for a communications class

Each writing situation involves a different purpose, audience, content, and context that must be considered by the author to make that communication effectively persuasive. In other words, when writing or speaking, the person should consider the purpose of the act, the audience that will receive the composition, and the content in which it will be presented. These considerations will influence the form or style that the composition takes.

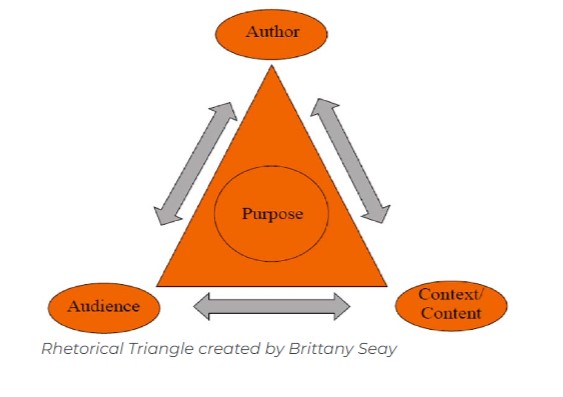

Figure 2.2 The Rhetorical Triangle

The four key factors of the rhetorical situation – author, audience, context, and content –all work together to influence the text’s purpose and how successful the author is in conveying that purpose to their audience. This can be represented by the rhetorical triangle featured above. In order to successfully rhetorically analyze any medium, you have to understand each of these aspects and how they not only affect the other aspects but how they are affected by the other aspects as well.

Purpose

Any time you are preparing to write, you should first ask yourself, “Why am I writing?” All writing, no matter the type, has a purpose. The purpose will sometimes be given to you (by a teacher or boss, for example), while other times, you will decide for yourself. As the author, it’s up to you to make sure that the purpose is clear not only for yourself but also for your audience. If your purpose is not clear, your audience is not likely to receive your intended message.

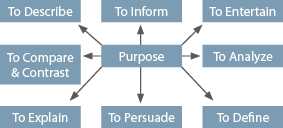

Figure 2.3 Types of Purpose

There are, of course, many different reasons to write (e.g., to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to ask questions), and you may find that some writing has more than one purpose. When this happens, be sure to consider any conflict between purposes, and remember that you will focus on one main purpose as the primary reason why you are engaging with that audience.

Bottom line: Thinking about your purpose before you begin to write can help you create a more effective piece of writing.

Questions for Consideration

Consider how the answers to the following questions may affect your writing:

- What is my primary purpose for writing? How do I want my audience to think, feel, or respond after they read my writing?

- Do my audience’s expectations affect my purpose? Should they?

- How can I best get my point across (e.g., tell a story, argue, cite other sources)?

- Do I have any secondary or tertiary purposes? Do any of these purposes conflict with one another or with my primary purpose?

Audience

In order for your writing to be maximally effective, you have to think about the audience you’re writing for and adapt your writing approach to their needs, expectations, backgrounds, and interests. Being aware of your audience helps you make better decisions about what to say and how to say it. For example, you have a better idea if you need to define or explain any terms, and you can make a more conscious effort not to say or do anything that would offend your audience.

Sometimes you know who will read your writing – for example, if you are writing an email to your boss. Other times you will have to guess who is likely to read your writing – for example, if you are writing a public social media post. You will often write with a primary audience in mind, but there may be secondary and tertiary audiences to consider as well.

Questions for Consideration

When analyzing your audience, consider these points. Doing this should make it easier to create a profile of your audience, which can help guide your writing choices.

- Background-knowledge or Experience — What does your audience know, think they know, and/or need to know? In general, you don’t want to merely repeat what your audience already knows about the topic you’re writing about; you want to build on it. On the other hand, you don’t want to talk over their heads. Anticipate their amount of previous knowledge or experience based on elements like their age, profession, or level of education.

- Expectations and Interests — What does your audience expect to read and what do they expect you to avoid writing about? Your audience may expect to find specific points or writing approaches, especially if you are writing for a teacher or a boss. Consider not only what they do want to read about, but also what they do not want to read about.

- Attitudes and Biases — What biases or attitudes might the audience have in relation to your topic? Your audience may have predetermined feelings about you or your topic, which can affect how hard you have to work to win them over or appeal to them. The audience’s attitudes and biases also affect their expectations – for example, if they expect to disagree with you, they will likely look for evidence that you have considered their side as well as your own.

- Demographics — Who is your audience? Consider what else you know about your audience, such as their age, gender, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, political preferences, religious affiliations, job or professional background, and area of residence. Think about how these demographics may affect how much background your audience has about your topic, what types of expectations or interests they have, and what attitudes or biases they may have.

Author

The next unique aspect of the rhetorical situation is the author. In some sense when you write, this is the part you have the most control over. You can harness the aspects of yourself that will make the text most effective to its audience, for its purpose. Analyzing yourself as an author allows you to make explicit why your audience should pay attention to what you have to say, and why they should listen to you on the subject at hand.

Questions for Consideration

- What personal motivations do you have for writing about this topic?

- What background knowledge do you have on this subject matter?

- What personal experiences directly relate to this subject? How do those personal experiences influence your perspectives on the issue?

- What formal training or professional experience do you have related to this subject?

- What skills do you have as a communicator? How can you harness those in this project?

- What should audience members know about you, to trust what you must tell them? How will you convey that in your writing?

Context and Content

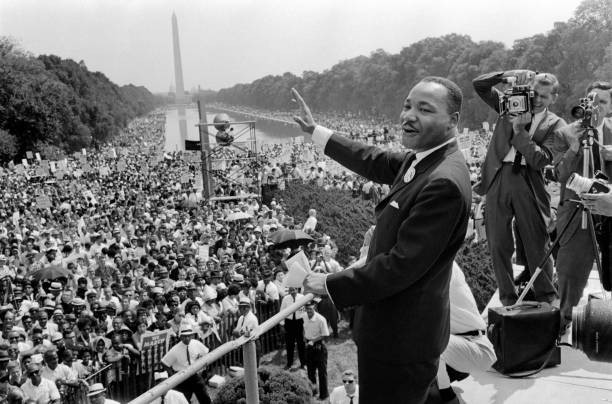

These words are easy for students to get confused as they are one letter away from being the same word; however, they could not be further from one another in meaning. Context refers to what is happening outside of the speech/article/medium that caused the need for the thing to exist or affected what was said/presented in the medium. For example, in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech “I Have a Dream,” he spoke during what some consider to be the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. This context not only affected what he said in his speech but how effective the examples he used were and who his audience was when he gave the speech.

Figure 2.4 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the 1963 March on Washington

On the other hand, Content is what is contained within the medium. Continuing to use “I Have a Dream” as an example, while the context was the Civil Right Movement, the content was the words that MLK Jr. spoke at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963. The content might feel simple and as though it doesn’t play that large of a role in the rhetorical situation as a whole because it feels automatic or obvious; however, as you analyze the other aspects of the rhetorical situation, you will find that each of the other aspects directly impacts what was said, how it was said, in what order, etc.

Additional Considerations for the Rhetorical Situation

Voice and Tone

Every speaker embodies a voice they use when speaking with others. Many factors central to the speaker can influence his or her voice—gender, ethnic background, upbringing, and education for example. Also, the situation we are in and our mood affect our voice; we sound different when we are happy, sad, angry, or being reprimanded by a parent or a boss. Finally, we can consciously assume different attitudes and tones of voice. Thus, we have many different methods, or registers, available to us when we speak. The same is true when we write. We can assume an objective, lawyer-like tone; we can write derisively, humorously, ironically, or angrily; we can write rapturously or bluntly.

The truth is, when we speak or write, we generally assume the voice to which we feel our audience will best respond. When you speak to your employer, for instance, you might focus on a respectful, contained tone so as not to break employer-employee etiquette. When speaking with a group of friends your own age, however, you will probably incorporate more intimate colloquial terms and even slang phrases. When telling a story, or sharing a personal experience, you might evoke a more familiar, casual tone.

The English language, for all of its grammatical rules and definitions, is an elastic language, capable of great reconfiguration and adjustment. It can handle the incorporation of words from other languages as well as new words. The idea that only one voice should be used for all your writing runs contrary to logic and creative practice.

Structure

Finally, once you have found the purpose for your writing project and directed it, with the right voice, to the chosen audience, you can engage in the process of finding the proper form for your words. Your writing’s structure comes directly from discovery and exploration, examining the variety of shapes and delivery methods for your own ideas. By engaging in this process and by permitting yourself—empowering yourself—to have a say, you are leaving the door open for a fresh exploration of the idea from which you may potentially draw conclusions in a profoundly new way. As you work through this process, consider the various rhetorical modes outlined in Chapter 10.

Genre

Figure 2.5 Examples of Genres of Communication

Genres are types of presentations (oral, visual, written) that adhere to certain formal conventions and produce certain expectations in their audiences based on culturally recognized symbols. For example, we know when watching television that a thirty-second public service announcement about municipal transportation is not like an academic lecture about the links between low household incomes and access to nutritious food. The audience knows this difference because of experience and social expectations and “receives” these two genres differently.

Key Takeaway – Why We Should Consider the Rhetorical Situation

As a writer, thinking carefully about the situations in which you find yourself writing can lead you to produce more meaningful texts that are appropriate for the situation and responsive to others’ needs, values, and expectations. This is true whether writing a workplace email or completing a college writing assignment.

As a reader, considering the rhetorical situation can help you develop a more detailed understanding of others and their texts.

In short, the rhetorical situation can help writers and readers think through and determine why texts exist, what they aim to do, and how they do it in particular situations.

Exercise 2.1

Listen to MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Answer the following questions to establish the rhetorical situation:

1. What is Dr. King’s purpose?

2. Who is his audience? (There may be more than one audience.)

3. Describe Dr. King’s voice and tone.

4. Is Dr. King’s speech an effective form of rhetoric?

Attributions

“Relaying & Responding: A Guide to College Reading & Writing” by Erik Wilbur, John Hansen, and Beau Rogers at Mohave Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Composition 1: Introduction to Academic Writing” by Brittany Seay is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Composition 2: Research and Writing”by Brittany Seay is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Image Credits

“Author” illustration of person sitting in front of table using laptop by Cytonn Photography via Pexels

Figure 2.2 is from “Composition 1: Introduction to Academic Writing” by Brittany Seay is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Figure 2.4 is from “The Relevance of MLK in Indian Country Today” by Levi Rickert. Image is by Wes Candela and is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Man screaming into phone photo by Icons8 Team on Unsplash

Women sitting on the couch talking photo by PICHA Stock

Figure 2.5 includes several photos:

- Social Media photo by Gerd Altman from Pixabay.com

- Protests photo by Freddy Kearney on Unsplash

- Music/Lyrics photo by Soundtrap on Unsplash

- Speeches photo by Jametlene Reskp from Unsplash

- Advertisements photo by Shiloh Dankert from Unsplash

- Conversations photo by Mimi Thian on Unsplash

Figure 2.1: Protestors: End Police Brutality photo by Tope. A Asokere on Unsplash,

Figure 2.1 Ads photo by Roméo A. on Unsplash

Figure 2.1 Person reading magazine photo by David Suarez on Unsplash

Figure 2.1: Stickers on wall photo by Gris Olmedo on Unsplash