Chapter 17: Integrating Sources

Joining a Conversation

Imagine you are meeting two of your friends for lunch at a restaurant. When you arrive, your friends are already there, engaged in a conversation about a current event. You sit down and listen, trying to come up to speed. More than likely, you will have something to contribute to the conversation. Each of your friends will have individual viewpoints, assumptions, and opinions. You may agree and disagree on varying aspects. Once you have a sense of the topic and what your friends have to say, you will join the conversation by contributing your own opinions.

Academic writing is not much different from the above scenario. As you read about a particular topic or issue, you will encounter the opinions and viewpoints of others. When you write an academic essay, you are contributing your own opinions and viewpoints to a particular type of conversation: an academic conversation.

As you express your opinions and viewpoints in writing, you will often be asked, even required, to incorporate research into your discussion. Incorporating outside sources into your academic writing serves several purposes. You can use them to provide background information relevant to your topic, support for your opinions, opposing viewpoints to address, or even as inspiration.

Learning to use sources with authority takes practice. There are two common pitfalls that occur when incorporating research into your writing:

Pitfall #1: You let the sources do the talking for you.

Pitfall #2: You use the words or ideas of your source(s) without giving credit.

Pitfall #1: Sources Speak for You

The first pitfall prevents you from expressing your own unique ideas; you do not contribute anything to the conversation. A paper like this will usually contain more quotes than your own writing.

To understand how the first pitfall happens, let’s go back to lunch with your two friends:

What would your friends think if you simply repeated what they said?

Jane: “I’m angry that tuition is being increased by thirty-two percent next year. I don’t know if I can afford to continue my education.”

Jeff: “I know. That’s crazy. I’m glad I finished my degree program last year, but I still cannot find a job in my field.”

You: “I’m angry that tuition is being increased by thirty-two percent next year. I don’t know if I can afford to continue my education. I know. That’s crazy.”

This example may seem silly, but it illustrates what happens when we use our sources as if they were our own ideas. Not to mention, you would probably get some pretty funny looks from your friends, who may not invite you to join them for lunch again.

Remember, incorporating outside sources into your academic conversation should support and illuminate your own ideas and what you have to say.

Let’s revise the lunch conversation to reflect a different approach:

Jane: “I’m angry that tuition is being increased by thirty-two percent next year. I don’t know if I can afford to continue my education.”

Jeff: “I know. That’s crazy. I’m glad I finished my degree program last year, but I still cannot find a job in my field.”

You: “I’m worried about the cost of education, too, Jane. Not only is it about to get a lot more expensive, but as Jeff mentioned, once I get the education, there’s no guarantee I’ll get a good job! Now, I’m wondering if I should focus more on getting an entry-level job and working my way up. Networking might be more cost-effective than a college degree.”

The revised conversation doesn’t simply repeat what Jane and Jeff said; it acknowledges their ideas (attribution) and builds on them. In this example, you’ve contributed your own insight and helped move the conversation forward.

In academic writing, you will want to similarly give attribution and join the conversation about your topic, not use someone else’s ideas in the place of your own.

Pitfall #2: Plagiarism

The second pitfall, however, is more serious and called plagiarism. This is covered thoroughly in Chapter 15.

To avoid plagiarism, which will result in serious consequences, remember the following:

- Give yourself plenty of time to complete an assignment. It’s more tempting to plagiarize when you are crunched for time.

- Understand your topic or issue and your own unique insight on the topic or issue. Your writing should express your ideas.

- As you research, identify the ideas of other writers and keep track of sources.

- Respond to the ideas of others in your writing and use them to support your own. Make sure you give them credit.

Why Use Sources

There are four main reasons to bring other voices into your conversation.

- Background information. Establish historical context or background information necessary for your audience to know to understand your argument.

- Support. As a type of evidence, an authoritative opinion from an expert or other credible source will help you build a logical connection to your claim. See Map of an Argument in Chapter 11 and Looking for Evidence in Chapter 13 for more information on types of support.

- Opposing viewpoint. A strong argument requires you to address opinions and views that oppose yours. This type of source may also provide a way into your discussion, if you choose to begin by identifying the opposition, then present your claim. See Addressing Opposing Viewpoints in Chapter 14 to learn about how these types of sources are useful.

- Inspiration. During the research process, you may have been inspired by a particular source, and this inspiration led to your own original ideas. Building on what another said is a normal conversation progression and appropriate for academic writing.

Attribution and Integration

Any time you bring another voice into your writing, you need to communicate some basic information to your reader in order to be clear where your words and ideas end and those of your sources begin. Conversely, your reader needs to be clear where your source’s words and ideas end and yours begin again. Attribution and documentation in academic writing employs a two-part system to communicate source information to the reader: in-text citations, which occur in the text of the essay, and a full list of bibliographic information, which occurs at the end of the essay. We cover these concepts in more detail along with two of the academic systems, MLA and APA, in this textbook.

For now, let’s focus on understanding the methodology of attribution within the text of the essay. Doing so will help you avoid unintentional plagiarism by making it clear to your reader which words and ideas are yours and which come from your sources. To craft in-text citations that successfully attribute source material, use a combination of signal phrases and in-text citations to communicate the following information to your reader:

- Author

- Location (page/paragraph/location)

- Author’s affiliation

- Title of work

- Container (see MLA/APA for determining container)

There are a variety of options for communicating the above information, much of which will be in the narrative of your writing (narrative lead-ins). In-text citations can be entirely in your narrative (except for page number), or partly in your narrative and partly in parentheses. The choices you make depend on how you intend to use the source. The name of the author and location may be enough. You may want to communicate the credentials and affiliation of the author to lend credibility. Perhaps there is no author or authorship is not significant. Again, make intentional, purposeful choices.

Bottom line: The information you include for the in-text citations must do the following:

- Direct the reader to the exact source on your bibliographic list (Works Cited or References).

- Indicate where your words and ideas end and those of your source begin as well as where your source’s words and ideas end and yours resume.

The next section introduces you to the various aspects and options available as you work to craft clear attributions.

How to Integrate Sources Properly

Armadillo Roadkill (Dropped Quotes)

Armadillo Roadkill (Dropped Quotes)

In the article, “Annoying Ways People Use Sources,” Kyle D. Stedman identifies a number of ways students misuse sources. The first one is “Armadillo Roadkill,” which is also called a floating quote or a dropped quote. Stedman’s description of armadillo roadkill is below:

Armadillo Roadkill (Dropped Quote): dropping in a quotation without introducing it first.

Everyone in the car hears it: buh-BUMP. The driver insists to the passengers, “But that armadillo—I didn’t see it! It just came out of nowhere!” Sadly, a poorly introduced quotation can lead readers to a similar exclamation: “It just came out of nowhere!”

And though readers probably won’t experience the same level of grief and regret when surprised by a quotation as opposed to an armadillo, I submit that there’s a kinship between the experiences: both involve a normal, pleasant activity (driving; reading) stopped suddenly short by an unexpected barrier (a sudden armadillo; a sudden quotation).

Example of Armadillo Roadkill

We should all be prepared with a backup plan if a zombie invasion occurs. “Unlike its human counterparts, an army of zombies is completely independent of support” (Brooks 155). Preparations should be made in the following areas. . .

Did you notice how the quotation is dropped in without any kind of warning? (Buh-BUMP.)

Armadillo Roadkill, as described by Stedman, is the main issue students face in incorporating sources. This has also been called a “floating quote” because it is just floating unanchored to the text around it or a “dropped quote” because it has just been dropped into the text randomly without context.

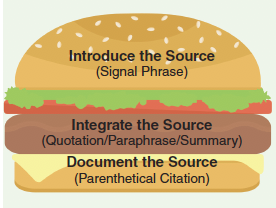

Quote Burger

One way to address this issue is to implement the “Quote Burger” method. In this metaphor, source material needs to be assembled into a burger before it can be served to the reader. Both buns complement each other and work as a team. Either one of them can help the reader locate the source on the Works Cited or References page.

Introduce the Source (Top Bun of the Quote Burger)

To build the Quote Burger, consider narrative lead-ins or signal phrases the top bun of the burger.

The top bun introduces the source material and puts you, as the writer, in command, allowing you to use the source for a specific purpose.

The top bun introduces the source material and puts you, as the writer, in command, allowing you to use the source for a specific purpose.

A narrative lead-in is where you narrate, or tell, the reader some of the source information. Signal phrases “signal” the reader that you are presenting words, ideas, and thoughts that are not your own. The terms signal phrase and narrative lead-in are often interchangeable; however, signal phrases are generally shorter and can appear at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of a sentence.

The following are simple examples for signal phrases that introduce quotations:

- X states, “_____.”

- As the prominent philosopher X puts it, “_____.”

- According to X, “_____.”

- X himself writes, “_____.”

- In her book, Title of the Book, X maintains that “_____.”

- In his article “Title of the Article,” X explains, “_____.”

- Writing in the journal, Title of the Journal, X complains that “_____.”

- In X’s view, “_____.”

- X agrees when she writes, “_____.”

- X disagrees when he writes, “_____.”

- X complicates matters further when she writes, “_____.”

Let’s revisit Stedman’s example of Armadillo Roadkill (“Dropped Quote”):

Stedman explains that fixing this dropped quote is “to set the stage for your readers—often, by signaling that a quote is about to come, stating who the quote came from, and showing how your readers should interpret it.”

He fixes the error above by inserting a narrative lead-in and a signal phrase.

Stedman explains, “In this version, I know a quotation is coming (“For example”), I know it’s going to be written by Max Brooks, and I know I’m being asked to read the quote rather skeptically (“he underestimates”). The sentence with the quotation itself also now begins with a “tag” that eases us into it (“he writes”).”

Note that he uses the phrase “he writes” as his signal phrase of choice. However, writers may use a variety of verbs to introduce a quote, such as the ones shown below.

Table 17.1 Verbs to Introduce Quote

|

Types of Verbs |

Examples |

|

Neutral signal verbs |

analyzes, comments, compares, concludes, contrasts, describes, discusses, explains, focuses on, illustrates, indicates, introduces, notes, observes, records, remarks, reports, says, shows, states, thinks, writes. |

|

Verbs of argument |

argues, asserts, believes, charges, claims, confirms, contends, demonstrates, finds, holds, maintains, points out, proposes, recommends, suggests |

|

Verbs of agreement |

agrees, concurs, confirms, supports |

|

Verbs of disagreement |

complains, contradicts, criticizes, denies, disagrees, questions, refutes, rejects, warns |

|

Verbs of concession |

acknowledges, admits, concedes, grants |

|

Strong signal verbs |

accepts, acknowledges, adds, admits, addresses, affirms, agrees, argues, asserts, believes, cautions, challenges, claims, comments, confirms, contends, contradicts, concedes, declares, denies, describes, disagrees, discusses, disputes, emphasizes, endorses, explains, grants, highlights, illustrates, implies, insists, maintains, negates, notes, observes, outlines, points out, proposes, reasons, refutes, rejects, reports, responds, suggests, thinks, urges, verifies |

Integrate the Source (The Meat of the Quote Burger)

Now that you have chosen a signal phrase or narrative lead-in, you can start preparing the “meat” in the Quote Burger.

Now that you have chosen a signal phrase or narrative lead-in, you can start preparing the “meat” in the Quote Burger.

In academic language, we call this incorporating the source because the source material becomes part of our written text. The meat of the burger, or the source material, may take the form of a quotation, a paraphrase, or a summary.

Each method of integration has unique characteristics (Table 17.2).

Table 17.2 Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing

|

Quoting |

|

Characteristics of a quotation: exact words of original source, quotation marks, accurate representation of original meaning, signal phrase, and citation. |

|

Paraphrasing |

|

Characteristics of a paraphrase: your own words communicate original meaning of source material, about the same length as original, signal phrase, and citation. |

|

Summarizing |

|

Characteristics of a summary: is similar to a paraphrase in that it communicates original meaning of source material in your own words using a signal phrase and citation. The difference between a paraphrase and a summary is length: a summary condenses the contents of a larger passage into a smaller summary of the content. |

|

Combination |

|

If you include unique terms or exact phrases in paraphrase or summary, be sure to indicate those with quotation marks. |

Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

Quoting

A quotation is one way you may make use of a source to support and illustrate points in your essay. A quotation is made up of exact words from the source, and you must be careful to let your reader know that these words were not originally yours. To indicate your reliance on exact words from a source, either place the borrowed words between quotation marks or if the quotation is four lines or more, use indentation to create a block quotation.

When Should I Quote?

Quote when the exact wording is necessary to make your point. For example, if you were analyzing the style choices in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, you would quote because it would be important to illustrate the unforgettable language or to use exact wording in a discussion of word choice and sentence structure. You would also quote if the exact wording captures information, tone, or emotion that would be lost if the source were reworded. Use quotations to assist with conciseness if it would take you longer to relate the information if you were to put it into your own words. Finally, if you cannot reword the information yourself and retain its meaning, you should quote it.

Source: It has begun. It is awful—continuous and earthquaking.

Quoting to preserve emotion: One nurse described an exchange between the two sides as “awful—continuous and earthquaking” (Burton 120).

How long should a quote be?

Quote only as many words as necessary to capture the information, tone, or expression from the original work for the new context that you are providing. Lengthy quotations can backfire on a writer because key words from the source may be hidden among less important words. In addition, your own words will be crowded out. Never quote a paragraph when a sentence will do; never quote a sentence when a phrase will do; never quote a phrase when a word will do.

Source: It has begun. It is awful—continuous and earthquaking.

Quoting everything: One nurse described an artillery exchange between the two sides: “It has begun. It is awful—continuous and earthquaking” (Burton 120).

Quoting key words: One nurse described an artillery exchange between the two sides as “awful—continuous and earthquaking” (Burton 120).

Paraphrase

A paraphrase preserves information from a source but does not preserve its exact wording. A paraphrase uses vocabulary and sentence structure that is largely different from the language in the original. A paraphrase may preserve specialized vocabulary shared by everyone in a field or discipline; otherwise, the writer paraphrasing a source starts fresh, creating new sentences that repurpose the information in the source so that the information plays a supportive role its new location.

Strategies for paraphrasing:

- Rearrange the order of information from the original source.

- Use a thesaurus such as www.thesaurus.com to replace keywords and terms. Be careful that synonyms do not alter the meaning.

- Replace jargon and technical terms with more common language.

- Include quotation marks around key terms or phrases.

When Should I Paraphrase?

Paraphrase when information from a source can help you explain or illustrate a point you are making in your own essay, but when the exact wording of the source is not crucial.

Source: The war against piracy cannot be won without mapping and dividing the tasks at hand. I divide this map into two parts: that which anyone can do now, and that which requires the help of lawmakers.

Paraphrase: Researchers argue that legislators will need to address the problem but that other people can get involved as well (Lessig 563).

If you were analyzing Lessig’s style, you might want to quote his map metaphor; however, if you were focusing on his opinions about the need to reform copyright law, a paraphrase would be appropriate.

What is effective paraphrasing?

Effective paraphrasing repurposes the information from a source so that the information plays a supportive role in its new location. This repurposing requires a writer to rely on their own sentence structure and vocabulary. A writer creates their own sentences and chooses their own words so the source’s information will fit into the context of their own ideas and contribute to the development of their thesis.

Source: Citizens of this generation witnessed the first concerted attempt to disseminate knowledge about disease prevention and health promotion, downplaying or omitting altogether information about disease treatment.

Effective Paraphrase: Murphy pointed out that in the first half of the nineteenth century, people worked hard to spread information about how to prevent disease but did not emphasize how to treat diseases (415).

When does paraphrasing become plagiarism?

A paraphrase should use vocabulary and sentence structure different from the source’s vocabulary and sentence structure. Potential plagiarism occurs when a writer goes through a sentence from a source and inserts synonyms without rewriting the sentence as a whole.

Source: Citizens of this generation witnessed the first concerted attempt to disseminate knowledge about disease prevention and health promotion, downplaying or omitting altogether information about disease treatment.

Potential plagiarism: People of this period observed the first organized effort to share information about preventing disease and promoting health, deemphasizing or skipping completely information about treating diseases (Murphy 141).

The sentence structure of the bad paraphrase is identical to the sentence structure of the source, matching it almost word for word. The writer has provided an in-text citation pointing to Murphy as the source of the information, but the writer is, in fact, plagiarizing because they haven’t written their own sentence.

What is Patchworking?

Patchworking occurs when too much of the original quote is left intact, without quotation marks. Patchworking should be avoided to ensure you do not plagiarize by failing to include quotation marks around quoted words.

Quotation: “According to the American Council on Science and Health, there is strong evidence that vegetarians have a lower risk of becoming alcoholic, constipated, or obese. The evidence is also strong that they have a lower risk of lung cancer. The evidence is good that vegetarians are less apt to develop adult-onset diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or gallstones.”

Unacceptable Patchworking: According to the American Council on Science and Health, there is strong evidence that vegetarians have a lower risk of becoming alcoholic, constipated, or obese. The evidence is also strong that they have a lower risk of lung cancer. The evidence is good that vegetarians are less apt to develop adult-onset diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or gallstones.

Acceptable Paraphrase: The Council summarizes “strong” evidence from the scientific literature showing that vegetarians have reduced risk of lung cancer, obesity, constipation, and alcoholism. The council also cites “good” evidence that they have a reduced risk of adult-onset diabetes, high blood pressure, gallstones, or hardening of the arteries.

Several strategies can help avoid patchworking and plagiarism while paragraphing. First, read a passage carefully and then put it away before trying to paraphrase it without looking at the original.

A passage may even be paraphrased twice to avoid patchworking. The first time, the writer should read the passage carefully and put it into his own words, looking at the source as little as possible. The second time, the writer should paraphrase his own paraphrase.

It is a good idea to recheck the final version of the paraphrase against the original to make sure all the similar sentence structures or word-for-word strings have been eliminated.

Exercise 17.1

One way to practice paraphrasing is to imagine you are taking the information and explaining it to someone else. Look at the following sentences and passages and then rephrase them in your own words, saying the new version out loud. Then have another person “say it again.” Can a third person “say it again?” Has the original meaning remained the same while each person’s phrasing varied?

- Central Arizona College is the only institution of higher learning in Pinal County, which is the size of Connecticut. This community college was founded in 1969 in Coolidge and now has five campuses strategically located throughout the county; it offers university transfer classes, a variety of certificates and two-year degrees, and personal enrichment opportunities.

- Xeriscaping is the idea of using little to no water for home landscaping. Plants and trees should be native species, and any that do require water receive it from recycled rain or household water. No grass is used.

- Find passages in the school paper or online articles. Read the passage aloud and see how many times others can “say it again,” paraphrasing effectively.

Exercise 17.2

1. One of the following paraphrases of the quotation below can be considered plagiarism. Which one?

Quotation: “Unlike extroverts, introverts become worn out or at times over-stimulated by the company of others. Therefore, introverts will seek solitude to regain their equilibrium and replenish their energy.”

Paraphrase A: Because being with people is sometimes too exhausting or too exciting for introverts, they often need time alone to restore their energy and their balance.

Paraphrase B: Unlike outgoing people, introverts become fatigued or overexcited from the presence of other people. Therefore, introverts will search for seclusion to recover their balance and recapture their vigor.

2. One of the following paraphrases of the quote below can be considered plagiarism. Which one?

Quotation: “Email is less formal than a business letter or memo, but that does not mean that no rules apply. Sending email without a subject line, sending crude jokes or lewd pictures, or sending mass emailings about free kittens or lost earrings are no-nos in the corporate world.”

Paraphrase A: Email is more informal than some other forms of business communication, yet that does not mean that rules do not apply. Not having a subject line, sending dirty jokes or pornographic pictures, or emailing employees about lost glasses or free puppies is not proper in the world of business.

Paraphrase B: Email is an informal method of communication, but in a business situation, it is still inappropriate to send potentially offensive material or to mass mail messages that do not relate to business.

Summary

We discuss this at more length in Chapter 1, but an overview is below.

Summarizing is a way to condense lengthy material, include only the main ideas of a text, or leave out the smaller details. The writer must use his own words when summarizing the material. Summaries must be cited with in-text citations.

A summary should identify the author and title of the original passage if known. Restate the thesis of the original passage. List each main point from the original passage in order reworded into your own words. Avoid quoting if possible. Avoid patchworking where you use some of the original phrases but not others. Avoid bias or commentary. When you summarize, you should write in your own words and the result should be substantially shorter than the original text. In addition, the sentence structure should be your original format. In other words, you should not take a sentence and replace core words with synonyms.

How do you choose whether to use a quote, a paraphrase, or a summary?

A.A. Milne, author of the Winnie the Pooh books, declared, “A quotation is a handy thing to have about, saving one the trouble of thinking for oneself, always a laborious business.” Thus, paraphrasing (or summarizing) should be the method of choice. Using your own words keeps you in command of your writing and helps you establish an authorial voice.

If you choose to use quotations, you should have a specific and justified reason to surrender your voice to that of your source. Think of quoting like letting someone order dinner for you or pick out your new car. You probably would not surrender agency (the ability to act independently and make your own choices) in these circumstances, neither should you in your writing.

Direct quotations might be useful for the following reasons: the language of the original is important, or the voice of the source helps you establish credibility.

Table 17.3 An example of text that is summarized, paraphrased, and quoted

|

Original text |

Some dramatic differences were obvious between online and face-to-face classrooms. For example, 73 percent of the students responded that they felt like they knew their face-to-face classmates, but only 35 percent of the subjects felt they knew their online classmates. In regards to having personal discussion with classmates, 83 percent of the subjects had such discussions in face-to-face classes, but only 32 percent in online classes. Only 52 percent of subjects said they remembered people from their online classes, whereas 94 percent remembered people from their face-to-face classes. Similarly, liking to do group projects differs from 52 percent (face-to-face) to 22 percent (online) and viewing classes as friendly, connected groups differs from 73 percent (face-to-face) to 52 percent (online). These results show that students generally feel less connected in online classes. |

|

Summarized text |

Students report a more personal connection to students in face-to-face classes than in online classes. |

|

Paraphrased text |

Study results show a clear difference between online and face-to-face classrooms. About twice as many students indicated they knew their classmates in face-to-face classes than in online classes. Students in face-to-face classes were about two-and-a-half times more likely to have discussions with classmates than were students in online classes. Students in face-to-face classes were about twice as likely to remember classmates as were students in online classes. Students in face-to-face classes viewed group projects as positive about two-and-a-half times more often than did students in online classes. Students in face-to-face classes saw class as a friendly place 73 percent of the time compared to 52 percent for online classes. Summing up these results, it is clear that students feel more connected in face-to-face classes than in online classes. |

|

Quoted text |

The study showed that personal discussions are much more likely to take place in face-to-face classes than in online classes since “83 percent of the subjects had such discussions in face-to-face classes, but only 32 percent in online classes.” |

|

Plagiarized text |

Some major differences were clear between Internet and in-person classrooms. For example, 73 percent of the study participants felt they were acquainted with their in-person classmates, but only 35 percent of the participants indicated they knew their distance classmates. |

Document the Source (Bottom Bun)

To finish the Quote Burger metaphor, let’s consider the bottom bun of our burger. In order to craft a complete in-text citation that helps the reader locate the source on the list of bibliographic work (Works Cited for MLA and References for APA), a parenthetical citation is often necessary.

To finish the Quote Burger metaphor, let’s consider the bottom bun of our burger. In order to craft a complete in-text citation that helps the reader locate the source on the list of bibliographic work (Works Cited for MLA and References for APA), a parenthetical citation is often necessary.

In order to clearly and completely attribute the words, ideas, or thoughts of someone else, writers use a combination of narrative lead-ins or signal phrases and parenthetical citations: parentheses that contain pertinent source information. Remember, in-text citations—citations that occur in the text of your writing—must point your reader to the full source entry on your Works Cited or References page.

Again, if the source has an author and a location, these must be communicated to the reader as part of the in-text citation; however, location information must always be presented in a parenthetical citation.

For MLA style, in-text citations need to convey the author’s last name and page number. Let style dictate how you include the author information. If you do not include the author’s name (or title of work if no author) in the narrative lead-in or signal phrase, use a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence(s) to do so. If the source contains a fixed location such as a page, paragraph, chapter, or digital location number, this information must be in a parenthetical citation. Do not narrate location. The MLA Handbook advises, “Part numbers in any source should be cited only if they are explicit (visible in the document) and fixed (the same for all users of the document). Do not count unnumbered parts manually” (123). Refer to the chapters in Part 5 for further information on formatting in-text citations in MLA style.

The following are some examples of parenthetical citations in MLA style:

(Last Name of the Author 55). (Gonzales 55). (Smith, Gordon 55).

(“Title of the Article” 55). (“Women in Advertising” 55).

(Title of the book 55). (Modern Hip-Hop 55).

APA style follows a similar pattern with one major difference: in-text citations must include the author (or title of work if no author) as well as the publication date for integrated sources. If the author is not named in the signal phrase, include it, along with the date and location in the parenthetical citation separated by commas: (Author’s Last Name, Year of Publication, Location). As with MLA style, location information must appear in parenthetical citations. Refer to the chapters in Part 5 for further information on formatting in-text citations in APA style.

The following are some examples of parenthetical citations in APA style:

(p. page number). (p. 55).

(Last Name of Author, Date, p. 55). (Gonzales, 2005, p. 55).

For variations like citing indirect sources (quote within a quote) and repeated sources, and punctuating in-text citations, refer to the chapters in Part 5.

Exercises

Instructions: For each question, read the works cited entry and the integrated quote options. Choose the option that is not properly integrated.

1.

Works Cited Entry:

Sanders, Leo. Design for Tomorrow: Urban Planning in the 21st Century. Harvard UP, 2022.

a. According to Sanders, “city infrastructure must adapt to population density increases” (112).

b. Population density is increasing. “City infrastructure must adapt to population density increases” (Sanders 112).

c. Population density is increasing, so “city infrastructure must adapt to population density increases” (Sanders 112).

2.

Works Cited Entry:

Holt, Miriam, and Jacob Fields. “Sleep Patterns of Young Adults.” Health Research Review, vol. 8, no. 1, 2023, pp. 50–72.

a. Holt and Fields argue that “lack of quality sleep disrupts cognitive performance” (63).

b. Research shows that “lack of quality sleep disrupts cognitive performance” (Holt and Fields 63).

c. “Lack of quality sleep disrupts cognitive performance” (Holt and Fields 63). Thus, it is important for students to get enough sleep.

3.

Works Cited Entry:

Patel, Suri, Linh Tran, and Omar Velasquez. Cognitive Frontiers. Stanford UP, 2021.

a. “Structured visual models improve long-term recall.” This is a quote from Cognitive Frontiers (Patel, et al. 289).

b. “Structured visual models improve long-term recall,” as shown in Cognitive Frontiers (Patel, et al. 289).

c. Patel, et al. note that “structured visual models improve long-term recall” (289).

4.

Works Cited Entry:

“Heat Waves Disrupt Midwest Harvests.” Agriculture Today, 2024, www.agToday.org/heatwave-report.

a. According to Agriculture Today, heat waves now “jeopardize harvest scheduling across the Midwest” (“Heat Waves Disrupt Midwest Harvests”).

b. Crops are being impacted by climate change. “Heat stress can jeopardize harvest scheduling across the Midwest” (“Heat Waves Disrupt Midwest Harvests”). This quote shows that heat waves are effecting crops.

c. The article “Heat Waves Disrupt Midwest Harvests” reports that heat waves now “jeopardize harvest scheduling across the Midwest.”

5.

Works Cited Entry:

“Air Pollution Levels Rise in Coastal Cities.” Environmental Data Institute, 2023, www.edi.org/coastal-air.

a. Air pollution has “increased dramatically along many coastal regions” (“Air Pollution Levels Rise in Coastal Cities”).

b. Cities along the coast are more likely to experience air pollution. “It has increased dramatically along many coastal regions” (“Air Pollution Levels Rise in Coastal Cities”).

c. The article “Air Pollution Levels Rise in Coastal Cities” argues that air pollution has “increased dramatically along many coastal regions.”

6.

Works Cited Entry:

Donahue, Carla. “Early Childhood Interaction Models.” Journal of Behavioral Development, vol. 59, no. 4, 2022, pp. 401–423.

a. Donahue claims that early peer interaction “shapes emotional adaptability later in life” (417).

b. Early peer interaction between children can make them emotionally stronger because this “interaction shapes emotional adaptability later in life” (Donahue 417).

c. Donahue claims that early peer interaction can make children emotionally stronger. “Such interaction shapes emotional adaptability later in life” (417)

Key Takeaways

- When you use sources, whether quoting, paraphrasing or summarizing, you are joining a conversation about a topic. Do not let the sources speak for you.

- Avoid plagiarism by always citing sources; put quotation marks around quoted words and include an in-text citation (signal phrase and parenthetical citation), as appropriate, to give credit to the source originator.

- The Quote Burger is a guideline for integrating sources into your writing by using 1. a signal phrase or narrative lead-in to establish context; 2. integration of the actual source material using quotation, paraphrase, or summary; and 3. a parenthetical citation to communicate author (if not mentioned in the signal phrase) and location/page number (if one exists).

Reminders, Tips, and Guidelines

- If the author or the title were already mentioned in the signal phrase, you no longer need to include them in the parenthetical citation (see previous explanation of “Attribution”).

- The format of the title must match that on the bibliographic list. If the title is in italics on the Works Cited, it will be in italics in your parenthetical citation. If the title is in quotation marks on the References list, it will be in quotation marks in your parenthetical citation.

- In MLA, there is no comma between the author’s last name and the page reference. There are no abbreviations, such as p., pp., or page(s) before page number(s).

- In APA, there are commas after the author’s last name and the date, followed by a “p.” and the number.

- The period is placed after the ending parenthesis.

- Summarizing is a way to condense lengthy material, include only the main ideas of a text, or leave out the smaller details. The writer must use his own words when summarizing the material. Summaries must be cited just like quotations and paraphrases.

Attributions

“Chapter 7 – How and Why to Cite” by Katelyn Burton is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Incorporating Sources by Kolette Draegan

Image Credits

Armadillo Photo by Suzanne D. Williams on Unsplash