Chapter 1: Active and Critical Reading Strategies

Expectations of Reading

|

High School Reading |

College Reading |

|

Primary Types: Textbook, literature |

Primary Types: Textbook, literature, persuasive analysis, research, multimedia sources, self-selected material |

|

Student Expectations: Read to find the main idea, share opinions, and make personal connections |

Student Expectations: Read to form new conclusions about the author or text, generate examples that support/refute a text and compare/contrast texts. Use texts to develop questions for further inquiry. |

|

Student Goals: Understand text and share reactions to the text, be able to answer questions posed by the teacher, and ask questions to clarify understanding. |

Student Goals: Analyze the text and synthesize to enter academic conversations on a topic, ask questions, and share insights with peers and professors to further the conversation. |

|

Teacher Expectations: Complete reading/assignment, answer who, what, when, where, and how questions, and share connections to the text. |

Professor Expectations: Develop thoughtful reactions to assignments, discuss the topics, focus on “why” questions, and share questions and answers about a topic. |

|

Teacher Goals: Check student understanding of the material through assignments (test, quizzes, papers, etc). |

Professor Goals: To guide and respond to student’s analysis and synthesis of information. Comprehension is assumed. |

|

If Problems Arise: Teachers may go out of their way to help students who are performing poorly on exams, missing classes, not turning in assignments, or struggling with the course. Students are often given “second chances” to complete and submit assignments. |

If Problems Arise: Professors may notice students performing poorly, but often expect students to be proactive and take steps to help themselves (i.e. attending office hours, emailing professors, etc.). “Second chances” are less common. |

Exercise 1.1

Write a brief reflection on how you approached assigned readings in the past. Did you skip them altogether? Did you use online notes and summaries instead of reading the material? Did you skim the material? Did you read everything assigned and take notes? Once you have considered how you read, consider the reasons behind your actions: why did you take the approach you chose? Do you feel your approach to reading had an impact on your education? Why or why not?

Reading as a Conversation

What would happen if you walked into the classroom before class, approached a group of strangers quietly chatting, and proceeded to announce to the group exactly what you were thinking at that moment? Most likely, the group would stop talking, look at you, laugh nervously, and slowly move away.

Let’s try another approach.

This time, you walk up and quietly join the group. You listen for a few minutes to figure out the topic being discussed and to understand the group members’ different perspectives before adding your own voice to the conversation. The response from the group in this scenario will likely be to engage with your ideas with interest. You have probably used this method many times throughout your life and have found it to work well, especially when joining a group of people you do not know very well. This method is the very same way to approach reading in your college courses.

To be a successful reader in college, you will need to move beyond simply understanding what the author is trying to say and think about the conversation in which the author is participating.

By thinking about reading and writing as a conversation, you will want to consider:

- Who else has written about this topic?

- Who are they professionally and personally?

- What is their perspective or argument on this topic?

- What type of evidence do they use to support their point of view?

In this chapter, we will introduce expectations for college reading, identify key strategies of skilled readers, and review the active reading process. Throughout the chapter, you will find links to samples, examples, and materials you may use.

We will also be introducing the concept of critical reading. Critical reading is moving beyond just understanding the author’s meaning of a text to consider the choices the author makes to communicate their message.

By learning to read critically, you will not only improve your comprehension of college-level texts, but also improve your writing by learning about the choices other writers have made to communicate their ideas. Honing your writing, reading, and critical thinking skills will give you a more solid foundation for success, both academically and professionally.

Reading critically does not simply mean being moved, affected, informed, influenced, and persuaded by a piece of writing. It refers to analyzing and understanding the writing’s overall composition and how it has achieved its effect on the audience.

This level of understanding begins with thinking critically about the texts you are reading. In this case, “critically” does not mean that you are looking for what is wrong with a work (although during your critical process, you may well do that). Instead, thinking critically means approaching a work as if you were a critic or commentator whose job it is to analyze a text beyond its surface.

This step is essential in analyzing a text, and it requires you to consider many different aspects of a text. Do not just consider what the text says; think about what effect the author intends to produce in a reader or what effect the text has had on you as the reader.

For example, does the author want to persuade, inspire, provoke humor, or simply inform the audience? Look at the process through which the writer achieves (or does not achieve) the desired effect and which rhetorical strategies are used. If you disagree with a text, what is the point of contention? If you agree with it, how do you think you can expand or build upon the argument put forth?

Consider the example below. Which of the following tweets below are critical and which are uncritical?

Figure 1.1 “Lean In Tweets”

Why Read Critically?

Critical reading has many uses. If applied to a work of literature, for example, it can become the foundation for a detailed textual analysis. With scholarly articles, critical reading can help you evaluate their potential reliability as future sources.

Finding an error in someone else’s argument can be the point of disruption you need to make a worthy argument of your own, illustrated in the final tweet from the previous image, for example. Critical reading can help you hone your own argumentation skills because it requires you to think carefully about which strategies are effective for making arguments, and in this age of social media and instant publication, thinking carefully about what we say is a necessity.

How many times have you read a page in a book, or even just a paragraph, and by the end of it thought to yourself, “I have no idea what I just read; I can’t remember any of it?” Almost everyone has done it, and it’s particularly easy to do when you don’t care about the material, are not interested in the material, or if the material is full of difficult or new concepts. If you don’t feel engaged with a text, then you will passively read it, failing to pay attention to substance and structure. Passive reading results in zero gains; you will get nothing from what you have just read.

On the other hand, critical reading is based on active reading because you actively engage with the text, which means thinking about the text before you begin to read it, asking yourself questions as you read it as well as after you have read it, taking notes or annotating the text, summarizing what you have read, and, finally, evaluating the text.

Completing these steps will help you engage with a text, even if you don’t find it interesting, which may be the case for assigned readings for some of your classes. In fact, active reading may even help you to develop an interest in the text even when you thought that you initially had none.

By taking an actively critical approach to reading, you will be able to do the following:

- Stay focused while you read the text

- Understand the main idea of the text

- Understand the overall structure or organization of the text

- Retain what you have read

- Pose informed and thoughtful questions about the text

- Evaluate the effectiveness of ideas in the text

The Active Reading Process

Before You Read

Establish Your Purpose

Establishing why you read something helps you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. Before you start to read, remind yourself what questions you want to keep in mind. Then establish your purpose for reading.

In college and in your profession, you will read a variety of texts to gain and use information (e.g., scholarly articles, textbooks, reviews). Some purposes for reading might include the following:

- to scan for specific information

- to skim to get an overview of the text

- to relate new content to existing knowledge

- to write something (often depends on a prompt)

- to discuss in class

- to critique an argument

- to learn something

- for general comprehension

Strategies differ from reader to reader. The same reader may use different strategies for different contexts because her purpose for reading changes. Ask yourself “why am I reading?” and “what am I reading?” when deciding which strategies work best.

Preview the Text

Once you have established your purpose for reading, the next step is to preview the text. Previewing a text involves skimming over it and noticing what stands out so that you not only get an overall sense of the text, but you also learn the author’s main ideas before reading for details. Thus, because previewing a text helps you better understand it, you will have better success analyzing it. To skim a text means to look over a text briefly in order to get the gist or overall idea of it. When skimming, pay attention to these key parts:

Table 1.2 Example Questions to Ask a Text

| What to Look For | Question to Ask |

| Title | What is the title of the text? Does it give a clear indication of the text’s subject? |

| Author | Who is the author? Is the author familiar to you? Is any biographical information about the author included? |

| Summary

|

If previewing a book, is there a summary on the back or inside the front of the book? |

| Introduction and Conclusion | What main idea emerges from the introductory paragraph? From the concluding paragraph? |

| Organizational Signposts | Are there any organizational elements that stand out, such as section headings, numbering, bullet points, or other types of lists? |

| Bold/Italicized Terms | Are there any editorial elements that stand out, such as words in italics, bold print, or in a large font size? |

| Images | Are there any visual elements that give a sense of the subject, such as photos or illustrations? |

Once you have formed a general idea about the text by previewing it, the next preparatory step for critical reading is to speculate about the author’s purpose for writing.

- Purpose: What do you think the author’s aim might be in writing this text?

Activate Your Background Knowledge on the Topic

All of us have a library of life experiences and previous reading knowledge stored in our brains, but this stored knowledge will sit unused unless we consciously take steps to connect to it or “activate” this knowledge.

After previewing a text, ask yourself, “What do I already know about this topic?” If you realize that you know very little about the topic or have some gaps, you may want to pause and do some quick Internet searches to fill in those gaps. Internet searches, online encyclopedias, and news websites may all be used to help you quickly learn some of the key issues related to the topic.

As you read, you should consider what new information you have learned and how it connects to what you already know. Making connections between prior knowledge and new information is a critical step in reading, thinking, and learning.

While You Read

Improve Comprehension through Annotation

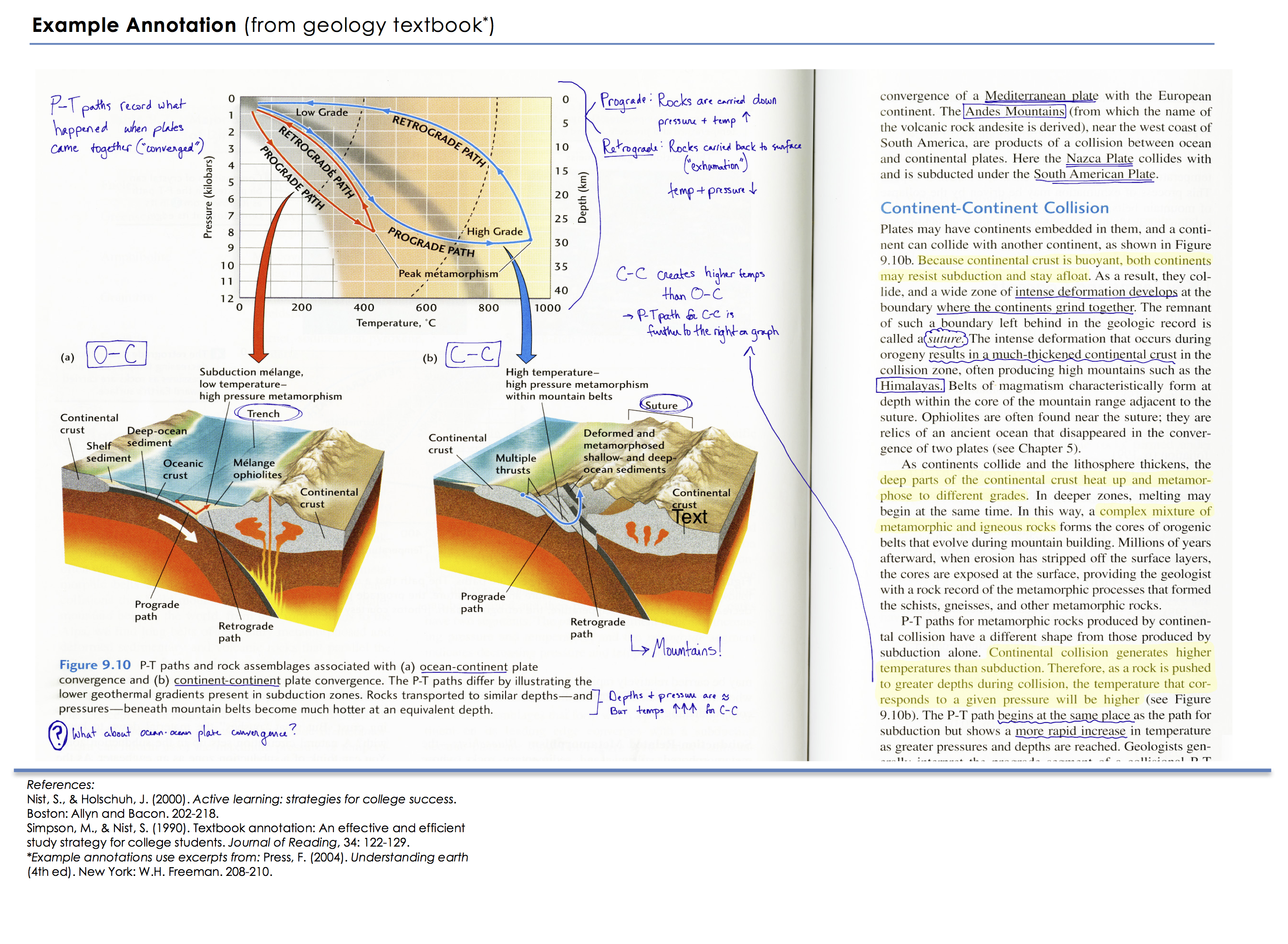

Annotating a text means that you actively engage with it by taking notes as you read, usually by marking the text in some way (underlining, highlighting, using symbols such as asterisks) as well as by writing down brief summaries, thoughts, or questions in the margins of the page. If you are working with a textbook and prefer not to write in it, annotations can be made on sticky notes or on a separate sheet of paper.

Regardless of what method you choose, annotating not only directs your focus, but it also helps you retain that information. Furthermore, annotating helps you to recall where important points are in the text if you must return to it for a writing assignment or class discussion.

Annotations should not consist of JUST symbols, highlighting, or underlining. Successful and thorough annotations should combine those visual elements with notes in the margin and written summaries; otherwise, you may not remember why you highlighted that word or sentence in the first place.

Figure 1.2 Example Annotation 1

Figure 1.3 Example Annotation 2

Following are our recommendations for how to annotate this textbook.

If You’d Like to Annotate On Your Screen:

- Using your device, navigate to https://pressbooks.pub/centralarizonacollege/

Select “Download this book” and a drop-down menu will appear. The drop-down menu contains a list of format options for downloading the textbook. - From the drop-down menu, select the format option that is best suited for your device. Here are some tips for choosing a suitable format from the drop-down menu:

-

- If you have a computer that contains Adobe Acrobat DC or a similar PDF editing application, select Digital PDF.

- The EPUB and MOBI formats are supported by many devices, including mobile phones, tablets (such as iPad), and eReaders (such as Kindle and Nook). Some devices allow for read-only by default, so you may need to obtain an additional application that will allow you to edit the textbook file.

After you download and open the textbook on your device, use your application’s built-in tools to highlight key content and add your own notes to refer back to later. Tip: In addition to annotating directly on the page, it’s a great idea to jot down notes in a separate notebook or document.

If You’d Prefer to Annotate on Paper:

- Using your device, navigate to https://pressbooks.pub/centralarizonacollege/

Select “Download this book” and a drop-down menu will appear. The drop-down menu contains a list of format options for downloading the textbook. - From the drop-down menu, select the Print_PDF format option to download the printable textbook. Tip: Before printing, check to be sure that you have enough ink and paper in your printer!

Decode Vocabulary

Understanding the vocabulary used in your college texts is a critical component of reading comprehension. Having strategies to use when you come across unfamiliar words will help you build and improve your vocabulary. You can sometimes determine the meaning of a word by looking within the word (at its root, prefix, or suffix) or around the word (at the clues given in the sentence or paragraph in which the word appears). If you are unable to determine the meaning of a word in context, you may look up the definition.

Each academic discipline has its own terminology, and part of your success in all your college courses will require you to move beyond simple memorization of word meanings to using these terms appropriately within the situation’s context. This means being aware that words have different meanings and connotations associated with them, and these meanings and connotations can change depending upon the situation in which they are being used.

Exercise 1.2: Context Determines Meaning

Match the correct meaning of the word synthesis to the context in which it is being used:

Context: Your English professor would like to see you use more synthesis within the body of your essay.

Definition #1: the combination of ideas to form a theory or system.

Definition #2: the production of chemical compounds by reaction from simpler materials.

Answer: You may get a failing grade on your essay if you combine chemicals to form an explosion, so you better go with definition #1!

Consider the Unique Qualities of the Text

The way you approach a text should vary based on the type of text you encounter. Reading a poem is very different from reading a chapter in a textbook. There are unique structures, elements, and purposes to the various texts you will encounter in college.

Below are some examples of active reading strategies employed with a variety of “texts” you might encounter in college including textbooks, scientific research, online media, artwork, and more. Notice how the readers approach the text differently based on the length, format, subject matter, and the reader’s own purpose for reading.

Table 1.3 Examples of Texts

|

Textbook |

Scholarly Research |

Online Media |

|

Persuasive Text |

Literature |

Visual Media |

After You Read

Once you’ve finished reading, take time to review your initial reactions from your first preview of the text. Were any of your earlier questions answered within the text? Was the author’s purpose similar to what you had speculated it would be?

The following steps will help you process what you have read so that you can move onto the next step of analyzing the text.

- Summarize the text in your own words (note your impressions, reactions, and what you learned)

- Talk to someone about the author’s ideas to check your comprehension

- Reread difficult parts of the text

- Review your annotations

- Answer some of your own questions from your annotations

- Connect the text to others you have read or researched on the topic

Once you understand the text, the next steps will be to analyze and synthesize the information with other sources and with your own knowledge. You will be ready to add your perspective, especially if you can provide evidence to support your viewpoint.

Just like with any new skill, developing your ability to read critically will require focus and dedication. With practice, you will gain confidence and fluency in your ability to read critically. You will be ready to join the academic conversations that surround you at HCC and beyond.

Writing Summaries

One of the best ways to test your understanding of a source is to summarize the information you gathered from it.

Summary Defined

A summary is a comprehensive and objective restatement of the main ideas of a text (an article, book, movie, event, etc.)

Stephen Wilhoit, in his textbook A Brief Guide to Writing from Readings, suggests that keeping the qualities of a good summary in mind helps students avoid the pitfalls of unclear or disjointed summaries. These qualities include:

Neutrality – The writer avoids inserting his or her opinion into the summary or interpreting the original text’s content in any way. This requires that the writer avoid language that is evaluative, such as: good, bad, effective, ineffective, interesting, boring, etc. Also, keep “I” out of the summary; instead, summary should be written in grammatical 3rd person (For example: “he”, “she”, “the author”, “they”, etc).

It can be easy and feel natural, when summarizing an article, to include our own opinions. We may agree or disagree strongly with what this author is saying, or we may want to compare their information with the information presented in another source, or we may want to share our own opinion on the topic. Often, our opinions slip into summaries even when we work diligently to keep them separate. These opinions are not the job of a summary, though. A summary should only highlight the main points of the article.

Brevity – The summary should not be longer than the original text, but rather highlight the most important information from that text while leaving out unnecessary details while still maintaining accuracy. Summaries are much shorter than the original material—a general rule is that they should be no more than 10% to 15% the length of the original, and they are often even shorter than this (the length is largely dependent on what you are using the summary for).

Independence – The summary should make sense to someone who has not read the original source. There should be no confusion about the main content and organization of the original source. This also requires that the summary be accurate.

Summary Organization

Like traditional essays, summaries have an introductory, body, and concluding material. What these components look like will vary some based on the purpose of the summary you’re writing. The introduction, body, and conclusion of a text focused on summarizing something will be different than in text where summary is not the primary goal. These elements are oftentimes much shorter as they are part of a condensed paragraph and not a fully developed argumentative paper.

Introductory elements in a summary

One of the trickier parts of creating a summary is making it clear that this is a summary of someone else’s work; these ideas are not your original ideas. You will almost always begin a summary with an introduction to the author, article, and publication so the reader knows what they are about to read. This information will appear again in your bibliography but is also useful here so the reader can follow the conversation happening in your paper.

In summary-focused work, this introduction should accomplish a few things:

- Author: Introduce the name of the author whose work you are summarizing.

- Title: Introduce the title of the text being summarized.

- Place of Publication: Introduce where this text was presented (if it’s an art installation, where is it being shown? If it’s an article, where was that article published? Not all texts will have this component–for example, when summarizing a book written by one author, the title of the book and name of that author are sufficient information for your readers to easily locate the work you are summarizing).

- Main Ideas (no examples): State the main ideas of the text you are summarizing—just the big-picture components. Avoid including examples. And present all main ideas in the same order as they appeared in the original.

- Context: Give context when necessary. Is this text responding to a current event? That might be important to know. Does this author have specific qualifications that make them an expert on this topic? This might also be relevant information.

Again, this will look a little different depending on the purpose of the summary work you are doing. Regardless of how you are using summary, you will introduce the main ideas throughout your text with transitional phrasing, such as “One of [Author’s] biggest points is…,” or “[Author’s] primary concern about this solution is….”

If you are responding to a “write a summary of X” assignment, the body of that summary will expand on the main ideas you stated in the introduction of the summary, although this will all still be very condensed compared to the original. What are the key points the author makes about each of those main big-picture ideas? Depending on the kind of text you are summarizing, you may want to note how the main ideas are supported (although, again, be careful to avoid making your own opinion about those supporting sources known).

When you are summarizing with an end goal that is broader than just summary, the body of your summary will still present the idea from the original text that is relevant to the point you are making (condensed and in your own words).

Since it is much more common to summarize just a single idea or point from a text in this type of summarizing (rather than all its main points), it is important to make sure you understand the larger points of the original text. For example, you might find that an article provides an example that opposes its main point to demonstrate the range of conversations happening on the topic it covers. This opposing point, though, isn’t the main point of the article, so just summarizing this one opposing example would not be an accurate representation of the ideas and points in that text.

More on Identifying the Main Idea and Supporting Details

Concluding a Summary

For writing in which summary is the sole purpose, here are some ideas for your conclusion.

- Now that we’ve gotten a little more information about the main ideas of this piece, are there any connections or loose ends to tie up that will help your reader fully understand the points being made in this text? This is the place to put those.

- This is also a good place to state (or restate) the things that are most important for your readers to remember after reading your summary.

- Depending on your assignment, rather than providing a formal concluding paragraph where you restate the main points and make connections between them, you may want to simply paraphrase the author’s concluding section or final main idea. Check your assignment sheet to see what kind of conclusion your instructor is asking for.

Reading is a recursive, rather than linear, activity. It is rare that you will read a text in college once, straight through from beginning to end. You may need to read a sentence or paragraph several times to understand it. Your reading will slow down or speed up as you encounter novels or familiar information. You may get “lost” in an example and need to double back or skip ahead to understand the point the author is trying to make.

Following is a summary of the strategies covered in this chapter that should help you read actively and critically.

- College-level reading and writing assignments differ from high school assignments in quantity, quality, and purpose.

- Managing college reading assignments successfully requires you to plan and manage your time, set a purpose for reading, implement effective comprehension skills, and use active reading strategies to deepen your understanding of the text.

- Finding the main idea and paying attention to textual features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Active engagement in the inquiry process is critical to success in college.

- College writing assignments place greater emphasis on learning to think critically about a particular discipline and less emphasis on personal and creative writing. Your focus becomes analyzing and synthesizing information to enter into academic conversations.

- Do not read in a vacuum. Simply put, don’t rely solely on your own interpretation. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading in and out of class to help clarify and deepen your understanding.

Attributions

“Critical Reading”, by Elizabeth Browning, Karen Kyger, and Cate Bombick is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

“Writing Summaries” by Brittany Seay is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Image Credits

Figures 1.1, 1.2. and 1.3 are from “Critical Reading”, by Elizabeth Browning, Karen Kyger, and Cate Bombick is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Figure 1.4, “Example Annotation” by The Learning Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Figure 1.5 “Example Annotation 2,” A Writer’s Guide to Mindful Reading by Ellen C. Carillo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0