Chapter 12: Rhetorical Appeals and Fallacies

“Humans aren’t as good as we should be in our capacity to empathize with feelings and thoughts of others, be they humans or other animals on Earth. So maybe part of our formal education should be training in empathy. Imagine how different the world would be if, in fact, that were ‘reading, writing, arithmetic, empathy.’” —Neil deGrasse Tyson

The Rhetorical Appeals

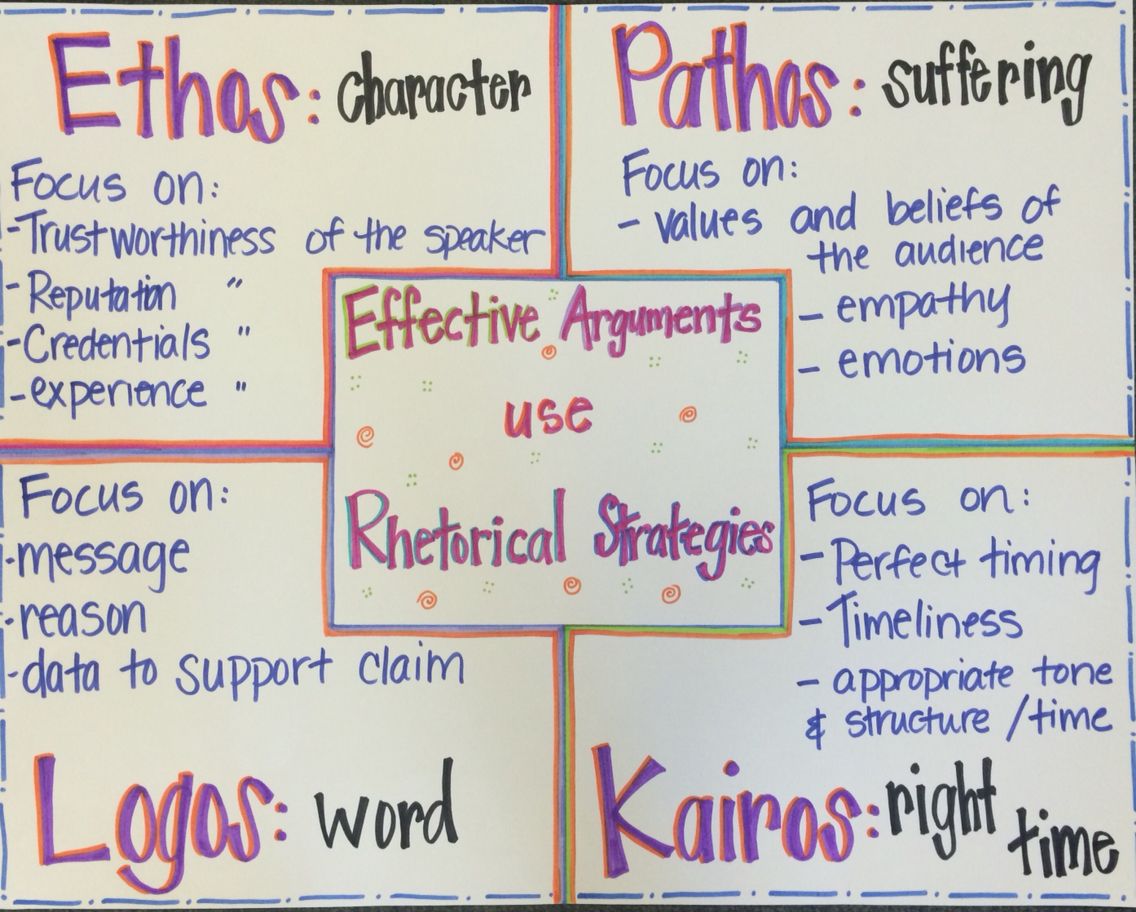

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. When persuading an audience, a writer or speaker will use many devices. Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle identified three rhetorical appeals—pathos, ethos, and logos—that he determined were utilized to successfully persuade. Another appeal often included in discussion of Aristotle’s appeals is kairos.

Watch this short video from Texas A&M’s Writing Center for an overview of ethos, pathos, and logos.

Pathos

Pathos refers to emotional appeals. Stirring emotions in an audience is a way to get them involved in the argument, and involvement can create more opportunities for persuasion and action.

Pathos can be expressed through words, pictures, or physical gestures. Because pathos is employed to specifically trigger the emotional states of the readers and listeners, it is powerful, but can be an incredibly manipulative method of appeal.

Intentionally stirring someone’s emotions to get them involved in an argument that has little substance would be unethical; however, speakers have taken advantage of people’s emotions to get them to support causes, buy products, or engage in behaviors that they might not if given the chance to see the faulty logic.

Since audiences may be suspicious of an argument that is solely based on emotion, effective speakers should use emotional appeals that are logically convincing. Emotional appeals are effective when you are trying to influence a behavior, or you want your audience to take immediate action. However, emotions lose their persuasive effect more quickly than other types of persuasive appeals. Since emotions are often reactionary, they fade relatively quickly when a person is removed from the provoking situation.

Using Pathos Correctly

Whether we are making arguments or analyzing them, it is important that we use pathos carefully. Often, our emotions can get in the way of clear and critical thinking on an issue. Pathos can and should be used to clarify how a well-supported position relates to our values and beliefs but should never be used to manipulate, confuse, or inflate an issue beyond what the evidence is capable of supporting.

An appropriate appeal to pathos is different from trying to unfairly play upon the audience’s feelings and emotions through fallacious, misleading, or excessively emotional appeals. Such a manipulative use of pathos may alienate the audience or cause them to “tune out.” An example would be the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) commercials featuring the song “In the Arms of an Angel” and footage of abused animals.

Even Sarah McLachlan, the singer and spokesperson featured in the commercials, admits that she changes the channel because they are too depressing.

Even if an appeal to pathos is not manipulative, such an appeal should complement rather than replace reason and evidence-based argument. In addition to making use of pathos, the author must establish her credibility (ethos) and must supply reasons and evidence (logos) in support of her position. An author who essentially replaces logos and ethos with pathos alone does not present a strong argument.

Examples

Common Examples of Pathos

- The “Made in America” label on various products sold in America tries to enhance sales by appealing to customers’ sense of patriotism.

- Ads encouraging charitable donations show small children living in horrific conditions to evoke pity.

The Science of Emotions

The following three TED Talks each address the science and growing body of research that explores the biological origins of our emotional states and what we can learn about ourselves from carefully studying our feelings. While not addressing the techniques of argument analysis and critical thinking directly, we can learn a great deal from these talks about the way pathos is used to influence our choices, perceptions, thoughts, values, and beliefs.

TED Talk Videos Recap:

- Humans are complex, emotional creatures who use their feelings as much as, or even more than, their thoughts to make decisions in the world.

- Even though scientists have graphed close to 35,000 distinct emotions, most people only feel around 10-12 of them with any regularity.

- Of those top 12, the overwhelming majority of people make most of their decisions based on just three: love, hatred, and fear.

- We make, on average, around 33,000 individual choices a day. If the data is correct, most of those decisions are governed, at least in part, by our reactions to our internal states of love, hatred, and/or fear.

- So, if we are not aware of (and at least somewhat in control of) how we process these emotions, anyone who wishes to manipulate us (politicians, advertisers, abusive partners, etc.) can use pathos in manipulative ways to trigger states of love, hatred, or fear to make us more susceptible to a given argument without fully considering the merits of its evidence.

Ethos

Ethos (referred to as ethics or credibility) is used to convince an audience via the authority (i.e., credibility or trustworthiness) of the writer. This credibility can come from one of two places.

1. A writer can have pre-established credibility. That is, their name is recognizable and carries with it a certain amount of believability or trustworthiness. For example, the leader of a country is typically granted some level of credibility even though few people under his or her leadership have personally interacted with or even met the leader of the country they live in. Even people who are considered popular celebrities have some level of pre-established credibility depending on the topic and context in which the discussion is taking place.

2. However, for most writers, the ethos they have is not established simply by placing their name on the paper or approaching the microphone. For many academics, ethos is determined by the tone, style, and sources or support they use to make their argument. Ethos developed in this manner includes two dimensions: competence and trustworthiness.

- Competence refers to the perception of an author’s expertise in relation to the topic being discussed. An author can enhance their perceived competence by presenting an argument based on solid research that is well organized and logically sound. Competent authors must know the content of their topic/argument and be able to effectively deliver that content.

- Trustworthiness refers to the degree that audience members perceive an author to be presenting accurate, credible information in a non-manipulative way. Perceptions of trustworthiness come largely from the content of the argument. Trustworthy authors consider the audience throughout the argument-making process, present information in a balanced way, do not coerce the audience, cite credible sources, and follow the general principles of communication ethics.

Examples

Common Examples of Ethos

- Advertisements for toothpastes often cite the recommendation of “9 out of ten dentists,” using the credibility of dental doctors as proof of the product’s effectiveness.

- In court, an expert witness might discuss their credentials to prove they are an authority on the subject at hand.

Using Ethos Correctly

- are shared with the readers/audience

- do NOT hide or obscure the fact that the argument has little to no logical support

- do not unfairly promote hatred or fear without sufficient cause.

Logos

Arguments consist of statements which claim something is true or false. The conclusion of your argument is the point of the argument, the point of view being argued. The other statements serve as evidence or support for your conclusion; we refer to these statements as premises. If we are thinking critically, we will not accept a statement as true or false without good evidence or support, so our premises are important.

Supporting statements are called premises.

The statement that is being supported is called the conclusion.

Here are a couple of examples:

Examples

Capital punishment is morally justifiable since it restores some sense of balance to victims or victims’ families.

Premise: Capital punishment restores some sense of balance to victims or victims’ families.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is morally justifiable.

Example

Because innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially executed, capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

Premise: Innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially executed.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

It is worth noting the use of the terms “since” and “because” in these arguments. Terms or phrases like these often serve as signifiers that we are looking at evidence, or a premise.

Check out another example:

Example

All human beings are mortal. Heather is a human being. Therefore, Heather is mortal.

Premise 1: All human beings are mortal.

Premise 2: Heather is a human being.

Conclusion: Heather is mortal.

In this example, there are a couple of things worth noting:

First, there can be more than one premise. In fact, you could have a rather complex argument with several premises. If you’ve written an argumentative essay, you may have encountered arguments that are rather complex. Second, just as the arguments prior had signifiers to show that we are looking at evidence, this argument has a signifier (i.e. therefore) to demonstrate the argument’s conclusion.

So many arguments!!! Are they all equally good?

No, arguments are not equally good; there are many ways to make a faulty argument. In fact, there are a lot of different types of arguments and, to some extent, the type of argument can help us figure out if the argument is a good one. For a full elaboration of arguments, take a logic class! Here’s a brief version:

Deductive Arguments: in a deductive argument the conclusion necessarily follows the premises. Take the above argument as an example:

Example

All human beings are mortal. Heather is a human being. Therefore,

Heather is mortal.

Premise 1: All human beings are mortal.

Premise 2: Heather is a human being.

Conclusion: Heather is mortal.

It is absolutely necessary that Heather is a mortal, if she is a human being and if mortality is a specific condition for being human. We know that all humans die, so that’s tight evidence. This argument would be a very good argument; it is valid (i.e the conclusion necessarily follows the premises) and it is sound (i.e. all the premises are true).

Inductive Arguments: in an inductive argument the conclusion likely (at best) follows the premises. Let’s have an example:

Example

98.9% of all CAC students like pizza. You are a CAC student. Thus, you like pizza.

Premise 1: 98.9% of all CAC students like pizza

Premise 2: You are a CAC student.

Conclusion: You like pizza.

In the above example, the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow; it likely follows. But you might be part of that 1.1% for whatever reason. Inductive arguments are good arguments if they are strong. So, instead of saying an inductive argument is valid, we say it is strong. You can also use the term sound to describe the truth of the premises, if they are true. Let’s suppose they are true, and you absolutely love pizza. Let’s also assume you are a CAC student. So, the argument is really strong, and it is sound.

There are many types of inductive argument, including: causal arguments, arguments based on probabilities or statistics, arguments that are supported by analogies, and arguments that are based on some type of authority figure. So, when you encounter an argument based on one of these types, think about how strong the argument is. If you want to see examples of the different types, a web search (or a logic class!) will get you where you need to go.

Watch this video for more on inductive and deductive reasoning.

In addition to using logical reasoning, authors employ logos by presenting credible information as supporting material and citing their sources during their argument. Research shows that messages are more persuasive when arguments and their warrants are made explicit. Carefully choosing supporting material that is verifiable, specific, and unbiased can help a speaker appeal to logos.

Finally, speakers can be more effective persuaders if they bring in and refute counterarguments. The most effective persuasive messages are those that present two sides of an argument and refute the opposing side. In short, by clearly showing an audience why one position is superior to another, speakers do not leave an audience to fill in the blanks of an argument, which could diminish the persuasive opportunity and the author’s credibility (ethos).

Examples

Common Examples of Logos

- A speech about climate change cites recent studies published in peer reviewed journals.

- A public service announcement gives statistics about the number of deaths attributed to texting and driving.

Using Logos Correctly

When someone asks, “What is your argument based on?” they are asking for logical support and reasoning. For academic writers, the appeal to logos is derived from the use of inductive or deductive reasoning; our use of credible sources; and the subsequent discussion concerning why that evidence supports our opinion.

When you offer evidence, expert testimony, statistics, facts, and other rational “support” for your argument, you are using logos. The proper use of logos in an argument will offer support that is sufficient, relevant, and representative of the best available evidence on the subject. But rational support of an argument is much more complex than it may seem at first as we will see when we examine logical fallacies later in this chapter.

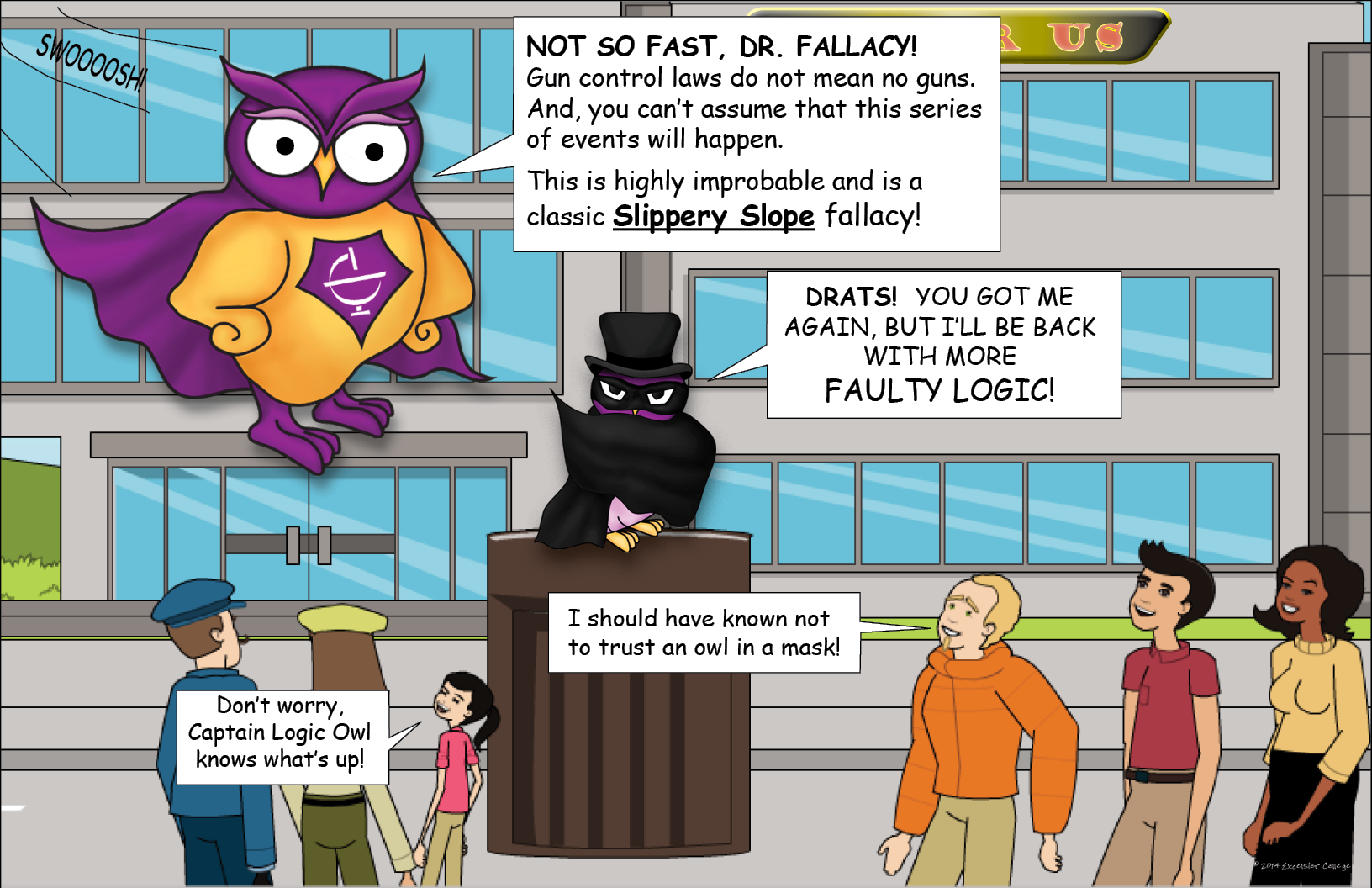

Combining Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

Rhetorical appeals often coexist together. Viewing or analyzing rhetorical appeals separately is important, but the writer should also understand how rhetorical appeals connect to one another.

Rhetorical appeals often coexist together. Viewing or analyzing rhetorical appeals separately is important, but the writer should also understand how rhetorical appeals connect to one another.

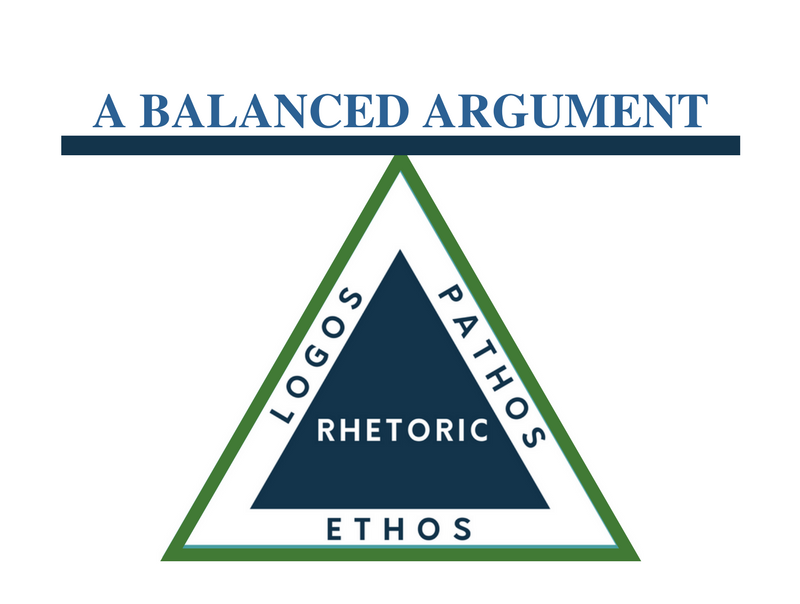

Figure 10.1 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. waves at the crowd on August 29 1963 at a civil rights rally in Washington DC

For example, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. applied all rhetorical appeals in his famous speech “I Have a Dream.” He shares his own experience with emotional and truthful stories (pathos) of his past and present circumstances as an African American man struggling with discrimination during the Civil Rights Movement. He uses historical references to slavery and refers to direct passages (logos) in the Constitution about freedom. He establishes credibility and trustworthiness (ethos) by his own experiences and knowledge about the topics in his speech.

Click this link to watch a video of the “I Have a Dream” speech and read a transcript.

Today, these same rhetorical devices can be seen in advertisements. For example, the “P90X” fitness company uses personal stories of real clients’ results of losing weight while using their exercise videos. The clients show their before and after pictures of weight loss. These drastic comparisons can provoke the emotions (pathos) of the viewer. The advertisement shows “inches lost” (logos) by using P90X. The advertisement establishes credibility (ethos) by showing results and knowledge about health and weight loss.

Kairos

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the text you are creating or analyzing. Rhetoric takes place in a specific time, context, and/or place, which is called “kairos.” Kairos can affect the way the message is given and received. To understand a text’s rhetorical situation, examine the audience and author’s setting and ask yourself if there was a particular occasion or event that prompted the text at the time it was written. This consideration of the Kairos is often translated as timeliness, which emphasizes the importance of time or timing in a rhetorical situation. Discussion of time as part of a rhetorical situation might range from the expansive to the minute: the early 21st century was a time of great technological change; 2020 was the time for virtual classrooms; the first day of class may not have been the best time for a pandemic joke.

Key Takeaways

- Pathos: Emotional appeals are used to engage an audience’s feelings, enhancing persuasion but must be balanced with logic to avoid manipulation.

- Ethos: Credibility or authority of the speaker, established through expertise or trustworthy sources, strengthens the argument.

- Logos: Logical appeals based on evidence and reasoning, including inductive and deductive arguments, provide rational support.

- Kairos: The timing and context of an argument, ensuring the message is relevant and appropriate for the audience and situation.

- Integration: Effective arguments often combine ethos, pathos, and logos, exemplified by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech

Specific Rhetorical Devices: Beyond Ethos, Pathos, Logos, and Kairos

Most (all?) rhetorical devices (or strategies) are connected to ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos. There may be times, though, that we want to look beyond those four Greek terms and look at specific rhetorical strategies.

Keep in mind that any way a writer uses words, images, etc. to persuade a reader constitutes a rhetorical device. Recognizing these devices–and referencing the effect of these strategies in your writing–will lead to stronger, more convincing analyses.

Here are some examples. For a more comprehensive list, click here. You may also find this video useful.

Authorial Persona (Authority)

The role/voice the author assumes to make themselves appear to be an authority.

Characterization

The act of describing the qualities of a character (how the character is developed in ways that further the author’s argument.) Characterization is usually developed carefully and slowly, emerging throughout the entirety of a work, or immediately, through direct statements about the character. Many authors use both strategies for character development.

Figurative Language

Two common types of figurative language used in writing are metaphors and similes.

Metaphor: A metaphor directly compares unlike things. Example: The woman gracefully walked toward the evening of life.

Simile: A simile compares unlike things using “like” or “as.” Example: The crowd scattered like sheep.

Imagery

Strong visual impressions created through words, frequently but not exclusively using color. Anything that encourages the reader to form a visual image to match the words. Note how the following passage provokes the reader to visualize the event taking place. Imagery is usually used to “show” rather than simply “tell” the reader what’s taking place.

Provocation

The way in which a writer tries to shock or intentionally antagonize the reader.

Symbol

Something that represents or stands for or is thought to typify something else by association, resemblance or convention; especially, a material object used to represent something invisible, like an idea.

Tone

Manner of expression in speech or writing (angry, pleading, cheerful, conquered, hopeful, sorrowful, bored, etc.)

Logical Fallacies

In order to build a sound argument, it is critical to steer clear of what are known as logical fallacies. A logical fallacy is a breakdown in reasoning, and it can occur when there is an error in the “facts” or chain of reasoning presented, bias in the information that is used to persuade the audience or stereotyping of populations.

Although we often associate logical fallacies with political rhetoric, we also see flawed reasoning in others’ discourse as well; it is important then to familiarize yourself with what a logical fallacy is and common examples of fallacies to better evaluate others’ arguments as well as develop your own. Below is a list of common logical fallacies along with examples of each.

Ad hominem

Definition: This Latin word translates to mean “against the person.” In this fallacy, the writer will make remarks against the person’s character rather than the person’s argument.

Example

Ad populum/Bandwagon

Definition: This Latin word translates as “to the people” and can be termed as popular with people. It is also known as the bandwagon fallacy. This fallacy refers to a writer using information to get the reader on board with the majority’s viewpoint of the argument stated.

Example

False authority

Definition: This fallacy is used when a writer quotes an authority not credible for the situation being discussed.

Example

Example

Appeal to ignorance (Argumentum ad ignorantiam)

Example

Appeal to tradition

Definition: This fallacy will lead readers to believe that an argument is valid by basing it only on tradition.

Example

Appeal to pity

Definition: This fallacy plays on the reader’s emotions. Using an excuse to sway their audience to believe what they want them to believe.

Example

Begging the question

Definition: This fallacy means that the writer is trying to persuade the reader into believing their argument without giving supportive evidence. Therefore, “begging” the reader to be persuaded in the direction of the writer. (A very weak approach.)

Example

Here the claim that Joe is the rightful possessor of the bike is supported by the fact that Joe owns it. The problem is that ownership is essentially being the rightful possessor. Sometimes to analyze an example of begging the question, it can help to ask what would support the claim that “Joe owns the bike.” Maybe if Joe had a receipt, or the testimony of the salesperson, or other witnesses to Joe’s rightful acquisition of the bike. But what doesn’t support that Joe owns the bike is that they are the rightful possessor of the bike.

Cherry Picking/Card Stacking (aka Stacking the Deck)

Definition: This fallacy means that the writer is trying to persuade the reader into believing their argument by only providing data that supports their stance while ignoring all evidence that conflicts with it.

Example

Examples

In this video, a Weather Channel meteorologist responds to an article published on the website Breitbart that engaged in cherry-picking data to distort the facts.

Equivocation

Definition: This fallacy uses words that have a double (or ambiguous) meaning.

Definition: This fallacy uses words that have a double (or ambiguous) meaning.

Example

“Sugar is an essential component to the human body” (from an ad for sugar).

This example uses “sugar” to mean both blood glucose and the refined commodity used in baking, tea, and so on. Here we might respond, “I know my body needs glucose to function, but that doesn’t mean I need literal sugar to function.”

Example

False dichotomy; Black-and-white; Either/or

Definition: This fallacy refers to a writer who presents one or two viewpoints as the only alternatives when many more could be represented. By doing so, this leads the reader into a false sense of understanding.

Example

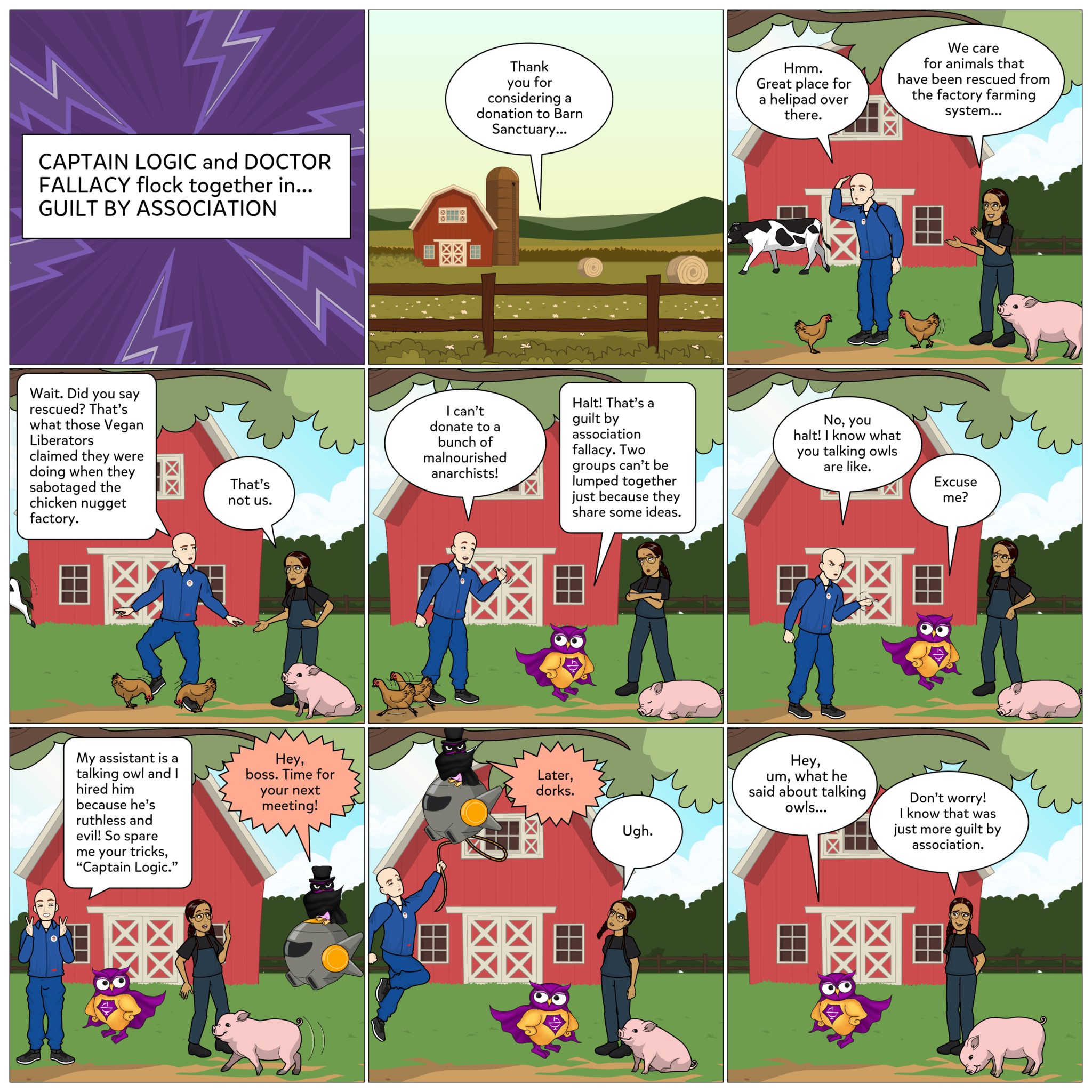

Guilt by Association

Definition: This fallacy claims something is true/false because it is similar to or associated with a clearly false idea/person and therefore must also be incorrect/correct.

Example

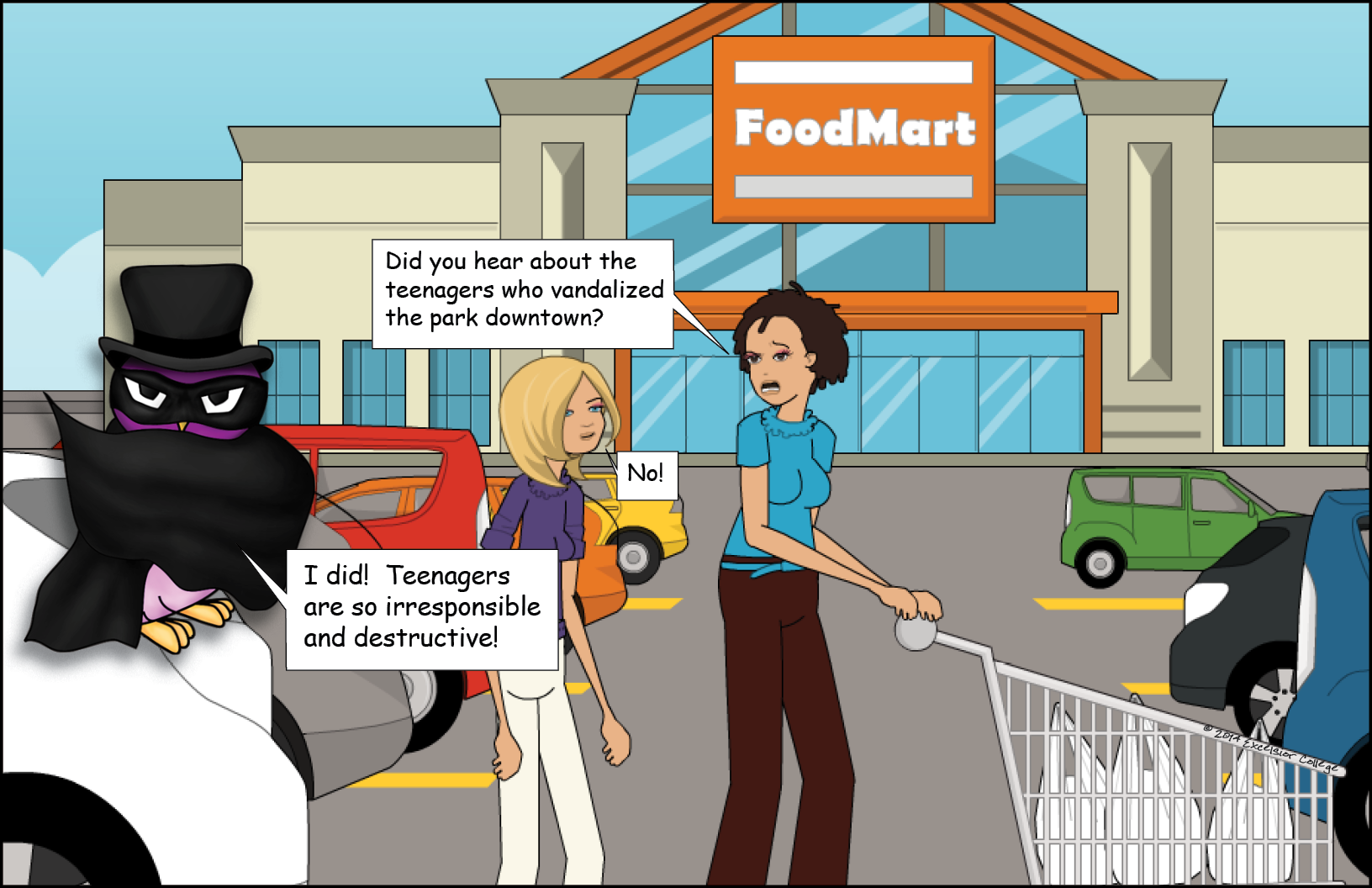

Hasty/Sweeping Generalization

Examples

- I saw a news story about a pit bull that attacked another dog; therefore, all pit bulls are vicious killing machines.

- Large scale polls were taken in Florida, California, and Maine, and it was found that an average of 55 percent of those polled spent at least fourteen days a year near the ocean. So we can conclude that 55 percent of Americans spend at least fourteen days near the ocean each year.

A particularly damaging example of the hasty generalization fallacy is the development of negative stereotypes. Stereotypes are general claims about religious or racial groups, ethnicities, nationalities, and other groups or communities. Even if we do have evidence that a certain trait is more common among people of one ethnicity, we still cannot assume that a particular individual of that ethnicity will have the trait. Applying stereotypes without consideration for how they fit the individual can lead to prejudice. Prejudice is a negative attitude and feeling toward an individual based solely on one’s membership in a particular social group. Because of holding negative beliefs (stereotypes) and negative attitudes (prejudice) about a particular group, people often treat the target of prejudice poorly, resulting in discrimination. Discrimination is negative action toward an individual as a result of one’s membership in a particular group.

A specific form of hasty generalization is when an author will point to a lack of evidence as a sign that no evidence is out there. This fallacy is often called appeal to ignorance because the arguer is citing their own lack of knowledge as the basis for their argument.

For example, consider the following: “No one I know has heard about any anti-Asian violence lately; therefore, reports of such violence are exaggerated.” The speaker and their acquaintances may simply not have come in contact with the people who have experienced such incidents of violence.

Post hoc (also called false cause)

Definition: This fallacy concludes that one event caused another just because one occurred before the other.

Examples

- An athlete buys new shoelaces and then wins the big game. The athlete believes that the new shoelaces brought her luck and will not play a game without them.

- The sun always rises a few minutes after the rooster crows. So, the rooster crowing

causes the sun to rise. - Once the government passed the new gun laws, gun violence dropped by 10%,therefore the new gun laws are working and caused the occurrence of gun violence to drop.

Red Herring

Definition: This fallacy is used to get the reader off track of the main issue that is being discussed.

Example

Example

The question posed by Chuck Todd is this: Why did the press secretary, Sean Spicer, make a false claim about the size of the crowd at the inauguration? Conway replies, “[…] the day before, talking about falsehoods, […] we allow the press in and what happens? Almost immediately a falsehood is told about removing the busts of Martin Luther King jr. from Oval Office.” She does not answer the question about the false claim Spicer made and instead redirects the discussion to false claims made by others. (Note: This is the moment when the term “alternative facts” was coined.)

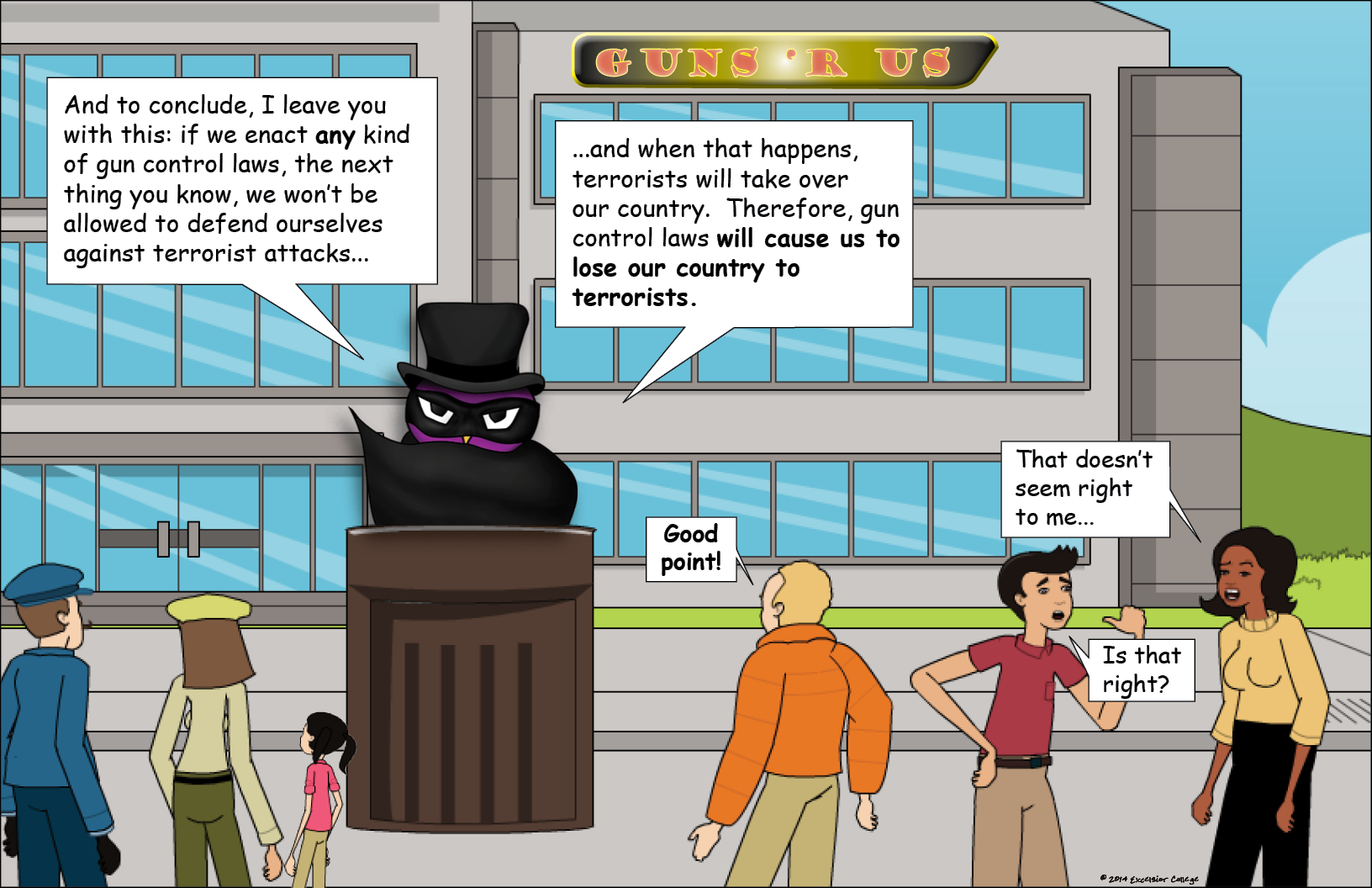

Slippery Slope

Definition: This fallacy means that one idea will ultimately lead to many more ideas that will result in a final outcome.

Examples

- If people continue to smoke and do not adhere to the warning signs that the public addresses, then our human race will ultimately suffer from health issues which will cause a rise in medical care. This will cause people to pay more money for medical care which will lead to more taxes.

- Also: “That escalated quickly.”

Straw man

Definition: This fallacy is used when the writer misrepresents an argument by an opponent in hopes of persuading the audience to their point of view.

Examples

- Person A: Everyone deserves equal pay regardless of gender. Person B: So a mother who stays home with children should make the same as a brain surgeon?

- Person A: Human beings’ actions are the cause of climate change. Person B: How can you say that I personally killed all the bees?

- Political party A: We need to raise taxes to better fund health care. Political party B: Party A just wants to take all your money and throw it away on executive salaries.

Weak/False analogy

Definition: This fallacy means that when someone compares two ideas or two situations that do not relate to one another, the argument becomes weak.

Examples

- An apple is red, and a tomato is red, and both are fruits, but both have very different tastes. The apple is sweet, and the tomato is savory.

- “If we can put a person on the moon, why can’t we figure out a way to make the tax code easier to understand?” This question doesn’t acknowledge the different skill sets and motivations involved in the two examples being compared.

The Logical Fallacies Short List offers a condensed list of fallacies with their definitions and brief examples for quick reference.

Using and Avoiding Logical Fallacies

Our use of logical support in arguments is subject to several possible corruptions along the way to a sound argument. Sometimes an arguer will commit these fallacies on purpose with the intent of fooling or manipulating the audience. But more often, we make these mistakes accidentally, with the best of intentions.

Regardless, if we are to evaluate and make sound arguments, we need to be able to spot the presence of logical fallacies, in our own arguments and in the arguments of others. The presence of a logical fallacy does not mean the entire argument is invalid, just that the particular reasoning is flawed or lacking in this one place. Finding and correcting logical fallacies can lead to making an argument stronger and easier to accept.

Other Resources

Exercise 12.1

Recognizing logical fallacies

Label each of the following fallacious statements with the appropriate term from the list below. (You will need to use some of the terms more than once):

- Our mayor had a successful acting career when he was a young man. He may say we don’t need a new courthouse in this city, but can you trust anyone who once learned to lie so well?

- Ever since Eric started working here at Bob’s Burgers, we’ve had fewer customers on Saturday nights. Obviously, Eric is at fault, and we need to get rid of him!

- Writing a book is like raising a baby. You have to stay up late with it, and you’ve always got it on your mind, whatever else you’re doing. Since I got paid leave from work when my son was born, I should get paid leave from work to get this book off to a good start.

- Since children of alcoholics will eventually become alcoholics too, we need to prevent children of alcoholics from ever getting their drivers’ licenses in order to keep our roads safe.

- The Smiths, the Browns, the Whites, and the Joneses are all moving out of Farquhar Farms and into Chompley Gardens. Chompley Gardens is obviously a much more comfortable place to live than Farquhar Farms.

- Annabelle DiMarco is a mother of four whose eldest son in is prison for statutory rape. Now we are asked to accept her contention that the landfill across from her family farm is leaking toxic wastewater into local streams. How can we trust the mother of a convicted felon to know the truth about anything, least of all a matter of such enormous public importance?

- The Campbell family down the street has requested a zoning variance that would allow them to build an apartment on their property to house Mrs. Campbell’s aging parents. Clearly, if we allow this variance, the Campbells, not to mention other area residents, will be eager to add structures to their property in order to house not just family members, but paying tenants as well. It will not be long before roads will be widened, hunting with be prohibited, and thousands of acres will be bull-dozed for gas stations and shopping malls –all to handle the ever-growing suburban population of our previously rural neighborhood.

- You can go back to school in the fall to finish your associate’s degree, or you can quit school, give up your degree, and work for the rest of your life in a sweatshop. It’s up to you.

- Once the new neighbors moved in next door, our guinea hens stopped eating. The noise these neighbors make, rehearsing their garage band, must be putting our birds off their food!

- Fizzy Cola has been the most popular soft drink in America for ten years–a testament to the high quality of its ingredients.

Terms: Logical Fallacies

- post hoc, ergo propter hoc

- bandwagon appeal

- ad hominem

- false analogy

- false premise

- false dilemma (a.k.a. false dichotomy)

- slippery slope

Key Takeaways

- A logical fallacy is a breakdown in reasoning, and it can occur when there is an error in the “facts” or chain of reasoning presented, bias in the information that is used to persuade the audience or stereotyping of populations.

- Logical fallacies can be accidental breakdowns in logic, but it is important to remember that they can also be used when the argument lacks enough evidence or support to be considered valid.

- Using logical fallacies to distract or distort the message is not ethical and can cause the audience to distrust the author.

Attributions

“Composition 1” by Brittany Seay is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Recognizing logical fallacies”, Emilie Ganter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Fallacies of Evading the Facts”, Eric Dayton and Kristin Rodier is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Logos: Critical Thinking, Arguments, and Fallacies”, Heather Wilburn is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Fallacies” by Christine James from Valdosta State University is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Persuasive Reasoning and Fallacies” by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Questioning the Assumptions by Anna Mills is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image Credits

Puppy by David Clarke on Unsplash

Man with tears by Tom Pumford on Unsplash

Woman with megaphone by Polina Tankilevitch on Pexels

Woman with file folder by Christina Morillo on Pexels

Doctor by Thirdman on Pexels

Man in Black Jacket Photo by ThisisEngineering on Unsplash

Charts on a Table by Lukas on Pexels

Pile of Books by Pixabay on Pexels

Balanced Argument Graphic from Let’s Get Writing! by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0,

Caution Sign Image by Image by Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay

McDonald’s Sign by Mike Mozart on Flickr is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Two women talking Image by Mircea Iancu from Pixabay

Dog with tree branch Image by Marco Leeggangers from Pixabay

Comics from “Logical Fallacies” by Excelsior OWL is licensed under CC BY 4.0