Chapter 14: Rhetorical Analysis of Visual Texts

Analyzing Visual Texts

Many people spend a substantial portion of their time watching and assessing images—including photographs, memes, graphs, and videos—via television, streaming services, and social media platforms. Even the college curriculum is as much visual as it is verbal, including Internet research, computer graphics, and slide show presentations. These forms of media might be relatively new, but people have been creating and consuming images for millennia, as you can see in the image below. An important part of human development consists of making images, enjoying them, and talking about them.

Figure 14.1: Visual Rhetoric

On the left is a carved medallion, found at Amaravati in a Buddhist shrine that dates from the later years BCE to the early CE. On the right, the individual images in the carving are outlined and numbered, explaining the narrative sequence and showing the audience how to “read” the medallion. Together, the two serve as an early example of visual rhetoric.

On the left is a carved medallion, found at Amaravati in a Buddhist shrine that dates from the later years BCE to the early CE. On the right, the individual images in the carving are outlined and numbered, explaining the narrative sequence and showing the audience how to “read” the medallion. Together, the two serve as an early example of visual rhetoric.

Formerly, visual texts were created exclusively by painters, photographers, and others generally designated as artists. Today, given the proliferation of technologies that enable the easy capture and manipulation of images, such visual texts are created by a multitude of authors. In this chapter, terms for these image creators—artist, author, composer, creator—are used interchangeably.

This chapter examines the elements of visual literacy and analysis most likely to complement the textual literacy emphasized in first-year writing classes. A critical understanding of visual texts is key to helping you both as a consumer of the frequent images you encounter in reading and viewing and as a producer who incorporates images into your own writing.

Overall, this chapter provides a solid basis for understanding visual rhetoric and communicating about it in various situations. After study and practice, you will be able to do so while drawing on your own cultural context, background, and experience and considering your audience, purpose, and rhetorical context.

Interpreting Visual Information

Both words and pictures convey information, but each does so in different ways that require interpretation. Interpretation is the sense a person makes of a piece of communication—textual, oral, or visual. It includes personal experience, the context in which the communication is made, and other rhetorical elements. By the time readers get to college, they have internalized strategies to help them critically understand a variety of written texts.

Images present a different set of challenges for critical readers. For example, in a photograph or drawing, information is presented simultaneously, so viewers can start or stop anywhere they like. Because visual information is presented this way, its general meaning may be apparent, while more nuanced or complicated meanings may take longer to figure out and are likely to vary from one viewer to another.

Figure 14.2 Person in Mask

Figure 14.2 depicts not merely a moment in time for the sake of memory; although, it certainly does that. It contains a central, dominant figure. The color red is bold and centers the figure, giving the image weight. It also conveys several political messages, both obvious and nuanced. The person in the picture is wearing a mask, as people were either asked or mandated to do during the COVID-19 pandemic. The slogan on their mask reads, “I can’t breathe,” words that were made infamous after Eric Garner (1970–2014) died as the result of an illegal chokehold inflicted by New York City police officer, Daniel Panteleo during arrest. These words were repeated by George Floyd (1973–2020) in an 8-minute, 46-second video showing his murder by Minnesota police officer. Derek Michael Chauvin, who knelt on Floyd’s neck. The phrase became one of several slogans of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, symbolizing the struggle that People of Color endure when living in an implicitly and explicitly racist culture. Breathing—like blood—is fundamental, essential. Without breath, there is no life. Thus, this slogan draws attention to the fact that People of Color may be brutalized for no reason other than their existence.

Placing the slogan on a mask is a design choice likely to provoke those who have argued against mandated mask wearing as an assault on personal liberty and who have proclaimed they could not breathe while wearing masks. Juxtaposition, or placing contrasting elements close together, is a technique that image creators often use for a variety of purposes: humor, irony, sarcasm, or—as in this case—disgust or outrage. The juxtaposition of the mask with a slogan referencing literal asphyxiation emphasizes the wearer’s view that state violence against People of Color is a more serious threat to their existence than a mask. Thus, the image is open to multiple interpretations.

Thinking Critically

To think critically about visual information, first identify the objects, facts, processes, or symbols portrayed in the image. Taking all the information together, consider the following questions:

- Is there a main or unifying idea?

- Is the meaning open to multiple interpretations?

- Is it suggested but not stated?

- Is it clear and unambiguous?

- Are there multiple levels of meaning, both stated and unstated?

When you view an image, pausing to answer such questions will sharpen your critical faculties, increase your understanding of the visual information you encounter, and help you use images more meaningfully in texts you create.

Visual Rhetoric

Written texts rely on strategies such as thesis statements, topic sentences, paragraphing, tone, and sentence structure to communicate their message to their audience. Images rely on different strategies, including point of view, arrangement, color, and symbol. When writing about images or including them in your writing, think critically about visual strategies and the effect they will have on your audience.

Using these techniques may or may not make you a proficient artist or creator of images. However, familiarity with the technical language of the visual arts will certainly enable you to describe what you observe as you build the evidence that allows you to interpret an image, reflect on it, analyze it, and make persuasive arguments about it.

Analyzing Images

When describing an image, you might state that a line is blue. When you analyze an image, you might discuss what the color and the line mean or do. The images of flags above are analyzed according to genre elements specific to visual media. In these discussions, the analysis begins with a description, but it does not end there. The elements of visual rhetoric are both described and analyzed to discover the artist’s intentions.

When describing an image, you might state that a line is blue. When you analyze an image, you might discuss what the color and the line mean or do. The images of flags above are analyzed according to genre elements specific to visual media. In these discussions, the analysis begins with a description, but it does not end there. The elements of visual rhetoric are both described and analyzed to discover the artist’s intentions.

When you analyze an image, you contribute to an ongoing global discussion, helping create the kaleidoscope that makes such rhetorical discussions meaningful. Do not worry about whether your contribution is right or wrong. Instead, consider its value to the global discussion. What can you say that would broaden understanding of the visual text and your experience of the world? This task may seem overwhelming, especially when you consider the work of a well-known artist. But your experiences and opinions are unique and valuable.

So far, this task sounds a lot like reflection, with one difference: reflection focuses on personal responses, reactions, feelings, and experiences, whereas analysis broadens that discussion to include the effects of various technical elements on a variety of people in different contexts.

When analyzing an image, consider some of the following questions:

- Why did the creator select these technical elements?

- How are various audiences likely to react to them?

- How have interpretations of the image changed over time, or how are they likely to change in the future?

- What effect does historical or current context have on your interpretation?

The Language of Visual Rhetoric

Images speak to viewers in a language that short-circuits their critical thought processes and goes directly to their sensory receptors. Yet unlike a simple, instinctive response to stimuli, the goal of critical thought, reflection, and discourse is to consider how and why viewers respond the way they do to certain images. To do so, viewers should consider the techniques that artists use to elicit such reactions. In this way, artists and viewers create a shared language of visual rhetoric in which both can discuss the virtues and demerits of a work of art as well as its historical and artistic contributions.

Key Terms in Visual Rhetoric

- Arrangement: Artists arrange their work to emphasize certain aspects and to create patterns of repetition and variation. The term composition is often used to mean arrangement.

- Color and symbol: Images communicate their meaning in part through the variety and interplay among colors. Even the choice to use black and white or a monochrome color palette is a color choice. Symbols in images allude to deeper meanings.

- Composition: Composition is often used as an umbrella term encompassing all aspects of visual rhetoric. It can also be used synonymously with arrangement to indicate how the piece is put together.

- Juxtaposition: In visual art, juxtaposition is the placement of contrasting images close together to emphasize their connection, lack of connection, or incongruity.

- Light: Unique to images is the use of light to highlight or obscure various parts of an image or to create prismatic effects that enhance its repetitive aspects.

- Line: In addition to outline shapes, artists use line to focus or center the viewer’s eye and then to move it across the image in certain predetermined patterns.

- Multimodality: Multimodality is the use of more than one type of literacy within a single work. For example, an airline display board is a multimodal work because it requires viewers both to understand ways of reading airport codes, time zones, and visual representations of temporal data and to relate that information to their current circumstances. Multimodality is a theory, perspective, or method that incorporates the consideration of all elements of an image.

- Point of view: Also called perspective, point of view encompasses what an image includes, what it excludes, and where its focus lies.

Point of View

In written texts, point of view refers to the “person” from whose vantage point the information is delivered, either a character in the story or a narrator outside the story. However, in photographs, drawings, and paintings, point of view refers to the place from which the image creator looks at the subject—where the photographer places their camera or the artist their easel. This point of view, then, also becomes the way someone views an image.

Photographs that haven’t been manipulated in a darkroom or digitally by a computer only reproduce the subject in front of the camera, as it exists in the moment the shutter opens and closes. They do not show anything to the left or right, above or below, or what comes before or after. A camera aimed to the east omits information from the north, west, and south. In other words, any photograph is the result of placing a camera in a certain location, at a certain height and distance, at a specific time of day and using a particular lens, film, and perhaps a filter. All these decisions about where, when, and how to place the camera create the visual point of view.

You can find good examples of these kinds of limited truths in real-estate advertisements featuring photographs of houses for sale. The photograph might not reveal a landfill next door or a factory across the street—though you might infer such limitations from a low selling price or confirm them by driving past the house.

Figure 14.3 “Kodak Digital Waterfall”

The creator of the above image chooses to highlight the digital waterfall with its seductive lighting and colors. Meanwhile, the people interacting with the computer are barely visible, standing off to the side, some nearly out of the frame. The silhouetted profiles and darkened faces lack identifying details. These features are emphasized by the blurred people in the background. These figures, too, are unidentifiable and are looking out of the frame, uninterested. The effect is to imply that the waterfall and its computer interface dominate human interaction and possibly even human existence.

To think critically about point of view, answer the following questions:

- From what place or stance does the image creator view the subject?

- What effect does this particular point of view have on the way viewers may think or feel about the subject?

- What would happen if the vantage point were elsewhere—above or below, left or right?

- What would change in the image if the point of view were changed?

Arrangement

In addition to point of view, artists use arrangement to signal an image’s significance to the reader. This aspect is also referred to as the image’s composition, or how it is put together. The term arrangement in visual texts might be compared to terms such as order, organization, and structure in verbal texts, though the differences are substantial. While writers arrange, or put together, a story, essay, or poem to take place over time—that is, the time readers need to follow the text, line by line, through a number of pages—image creators arrange pictures in the two-dimensional space of their viewfinder, paper, or canvas to invite viewers to read in space rather than time.

This difference is also evident in sculpture and other three-dimensional works, which require viewers to move around them to read them spatially. In visual texts, then, arrangement refers to the ways in which the various parts of a picture come together to present a single coherent experience for the viewer.

In contrast to static images, which are read spatially, videos and some types of multimodal texts—those incorporating more than one genre, discipline, or literacy (for example, GIFs that incorporate pictures or videos with language)—combine elements of both time and space. That is, they invite viewers to examine an image in motion that changes over time. Video creators often mimic linear time by telling a story, or they repeat key images to be interpreted differently after being seen in various contexts within the video.

One element to examine is the use of pattern—predictable, repeated elements within the visual field that the eye notices and seems attracted to. Just as sonnets, sestinas, and haiku follow patterns of lines, so do visual compositions. But in these, patterns are created by light and color rather than words. Documentary and commercial photographers often use visual patterns to lead viewers to an intended meaning. Patterns are especially prominent in street art, where the elements of surrounding architecture and infrastructure interact with the work, as shown in the following figure.

Figure 14.4 Gaza Strip mural in Prague, Czech Republic

Many patterns are suggested by mathematics. For example, the Möbius strip is both a mathematical construct and a visual enigma. It has one side and one boundary curve. It looks like a spiral, but it does not intersect itself. Thus, it gives the impression of being infinite. In the mural in Figure 14.4, the artist capitalizes on these features of the Möbius strip, using it to depict the seemingly endless cycle of destruction (green tanks) and reconstruction (yellow steamrollers) in one of the world’s most contested pieces of real estate: the Gaza Strip.

Ownership and control of the Gaza Strip are disputed. Approximately two million people live there, many in refugee camps. Since the mid-20th century, the region has been fought over by Israel, Egypt, and Palestinian Arabs. As you contemplate the mural, think about the way its creator uses pattern and repetition to convey various ideas and emotions.

The following questions may help:

- Which elements within the mural are repeated?

- Where is its center of gravity or weight?

- Where do patterns of light/dark, large/small, and color lead the eye?

- How do pattern and balance contribute to meaning in a two-dimensional image?

- What does the arrangement suggest about the meaning of the image?

Color and Symbol

Pattern and arrangement are controlled by the image creator and intended to guide the viewer. Color and symbol allow the viewer greater latitude in interpreting the image, in part because particular colors suggest specific moods and can provoke certain emotions or connotations.

Think about your personal reactions to different colors. What color might you select to paint your bedroom? What is your favorite color for, say, clothing or cars? While these may differ according to personal preference, traditional symbolic values are attached to different colors in literature and art. Why, for instance, does red often symbolize anger or war on the one hand and romance or passion on the other? Why does black often suggest danger or death? And why does white often stand for innocence or purity? Are the reasons for these associations arbitrary, cultural, or logical?

Particular colors also suggest or reinforce social and political ideas. What, for example, is suggested by adding a red, white, and blue American flag to a magazine advertisement for an American automobile, political poster, or bumper sticker? What is the meaning of a yellow ribbon tied to a tree in front of a house or an image of a yellow ribbon sticker attached to the tailgate of a pickup truck? By themselves, colors do not specify political positions, arguments, or ideas, but used in conjunction with specific words or forms—a flag or ribbon, for example—the emotional power of color can be influential.

Color associations globally are complicated and highly nuanced. The following overview is brief and simplified, to be considered merely as an introduction or starting point for your research and investigations into individual artistic expressions. When you interpret an artist’s use of color, one place to start is with the hues found in the natural world. Because blood is red, the color is often associated with life, heat, and passion. Yellow and green appear with the new growth of spring, so these colors often symbolize new beginnings, freshness, and hope. Both the sea and the sky are blue. Although these elements can be turbulent, many people find peace and tranquility as they reflect on them, and thus they are often associated with these emotions.

Regardless of colors’ natural associations, people from around the world understand colors differently. In China, for example, red is a celebratory color associated with holidays, feasts, and the giving of gifts, whereas in some parts of Africa the color may symbolize the sacrifice necessitated by the fight for independence. In the Western world, white can represent purity or innocence and is often worn by young women at their weddings. However, in parts of Asia, white is a color of mourning.

The colors mentioned so far are mostly primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. The secondary colors—orange, green, and purple—carry more complex meanings. Both orange and the bright shade of green called neon or chartreuse are easy to see in all light conditions. Therefore, they are often used for safety purposes, on caution signs or uniforms of emergency workers. Orange is associated with the robes of Buddhist monks, thus representing in Buddhist cultures that which is holy; whereas, in the Netherlands, orange is the color of the royal family and used for patriotic purposes.

In addition to connotations of spring, green is also associated with Islam. In the Christian tradition, yellow and gold are colors associated with riches and abundance. Holiness is also associated with blue in Egyptian, Hindu, and Christian cultures (in which blue has other associations as well). Because purple has traditionally been a difficult color to manufacture, its rarity meant that only the very wealthy, often nobility or royalty, could afford to wear it—hence its association with royals and even gods. However, some cultures, such as Thai, Brazilian, and Italian cultures, associate purple with bad luck or death.

Again, this overview of colors’ different interpretations and associations is not intended as a guide for interpreting color in a visual image. Instead, consider all of the different ways in which color can be understood, some ways that the artist might intend for color to be interpreted, and the associations that colors have for you when you view a visual or digital image.

In this chapter, you have begun learning about how to interpret visual information through the lens of rhetoric. Color and its related symbolism help viewers interpret images.

Symbols

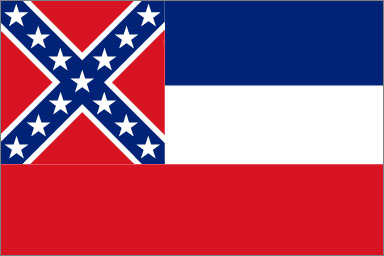

Figure 14.5 State flag of Mississippi, 1894–2020. This is the 1894 version, without the white stripe added in 1996.

Figure 14.6 The current state flag of Mississippi was adopted 2021.

Like colors, symbols are interpreted differently by individuals on the basis of their personal and cultural experiences. Above is an example of two state flags with very different symbolism: The first image depicts the state flag of Mississippi that was adopted in 1894; the second image depicts the one adopted in 2021.

In 2021, under pressure from numerous organizations and in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Mississippi replaced its state flag. The 1894 flag included the battle flag of the Confederacy, referencing Mississippi’s history of secession and violence during the Civil War (1861–1865); the single blue, white, and red bands were a reference to the stripes on the American flag. This historical allusion, coupled with the state’s history of enslavement and segregation, meant that the 1894 flag served as a stark reminder of efforts to silence Black Mississippians. In fact, Mississippi did not formally ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution—proposed in 1865 to abolish slavery—until 2013, and the state remained segregated long after the Supreme Court outlawed the practice.

Mississippi continued to use the 1894 flag throughout the Reconstruction (1865–1877) and the Jim Crow laws (ca. 1877–c. 1950) and civil rights (1950s and 1960s) eras despite multiple and sustained efforts to remove any reference to the Confederate flag. In 2020, the increasing prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement created the context in which state lawmakers were forced to consider these problems as mainstream and urgent. Further, the state came under pressure from numerous organizations, including the Southeastern Conference athletics organization (SEC), which threatened to boycott the state by no longer holding major events there if the flag were not changed.

Submitted to the legislature by Starkville-based graphic designer Rocky Vaughan (b. ca. 1977) and collaborators Sue Anna Joe, Kara Giles, and Dominique Pugh, the new flag took effect in January 2021 after voters approved it and the governor ratified it. The current flag features a central vertical band of blue, flanked by two thin gold bands and encompassed by two broader red ones. The flag’s center is dominated by a single magnolia flower, crowned by a single gold star and encircled by 20 white ones. Beneath the flower are emblazoned the words “In God We Trust.”

The gold coloring is intended to celebrate Mississippi’s contributions to the world of art, music, and literature. The white stars symbolize Mississippi’s status as the 20th state of the Union; thus, the new flag symbolizes the state’s reintegration into the Union without reference to its seditious acts in the 19th century or lingering loyalty to the beliefs that motivated them. In addition, the single gold star honors the state’s Indigenous people; no reference is made to the state’s history of enslavement and racism.

Thinking critically about color and symbol, ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the color enhance or distort the reality of the image?

- Imagine the image in shades of black, white, and gray. What would be lost and what would be gained if color were subtracted?

- Does the color work with or against the other compositional elements?

- What symbols are incorporated into the image? How might those symbols be interpreted in various contexts?

- What, if any, is the significance of referencing Indigenous but not Black Americans on the current flag?

Key Takeaways

- People spend a significant amount of time engaging with various forms of visual media, such as photographs, memes, graphs, and videos, especially through television, streaming services, and social media platforms.

- Both words and pictures convey information, but images present unique challenges. Interpretation of images requires considering personal experience, context, and rhetorical elements.

- Images use various strategies like point of view, arrangement, color, and symbol to convey messages. These differ from the textual strategies used in written communication.

- To think critically about visual information, one should identify the main idea, consider multiple interpretations, and analyze both the explicit and implicit meanings within the image.

- Describing an image involves stating observable features, while analyzing an image involves discussing the meanings and effects of these features.

- Visual Rhetoric Elements include:

- Arrangement/Composition: How elements are organized to create a coherent experience.

- Color and Symbol: Colors can evoke specific emotions and connotations; symbols can allude to deeper meanings.

- Juxtaposition: Placing contrasting elements close together to emphasize their relationship or incongruity.

- Light and Line: Use of light to highlight or obscure parts of an image and lines to direct the viewer’s eye.

- Interpretations of images can change over time and are influenced by cultural and historical contexts.

- Analyzing images contributes to a broader global discussion, enriching the collective understanding of visual texts and their impact on society.

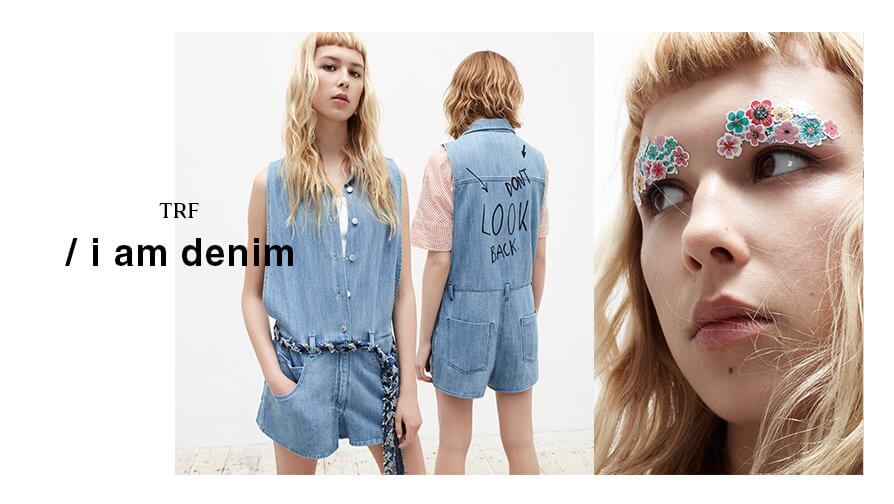

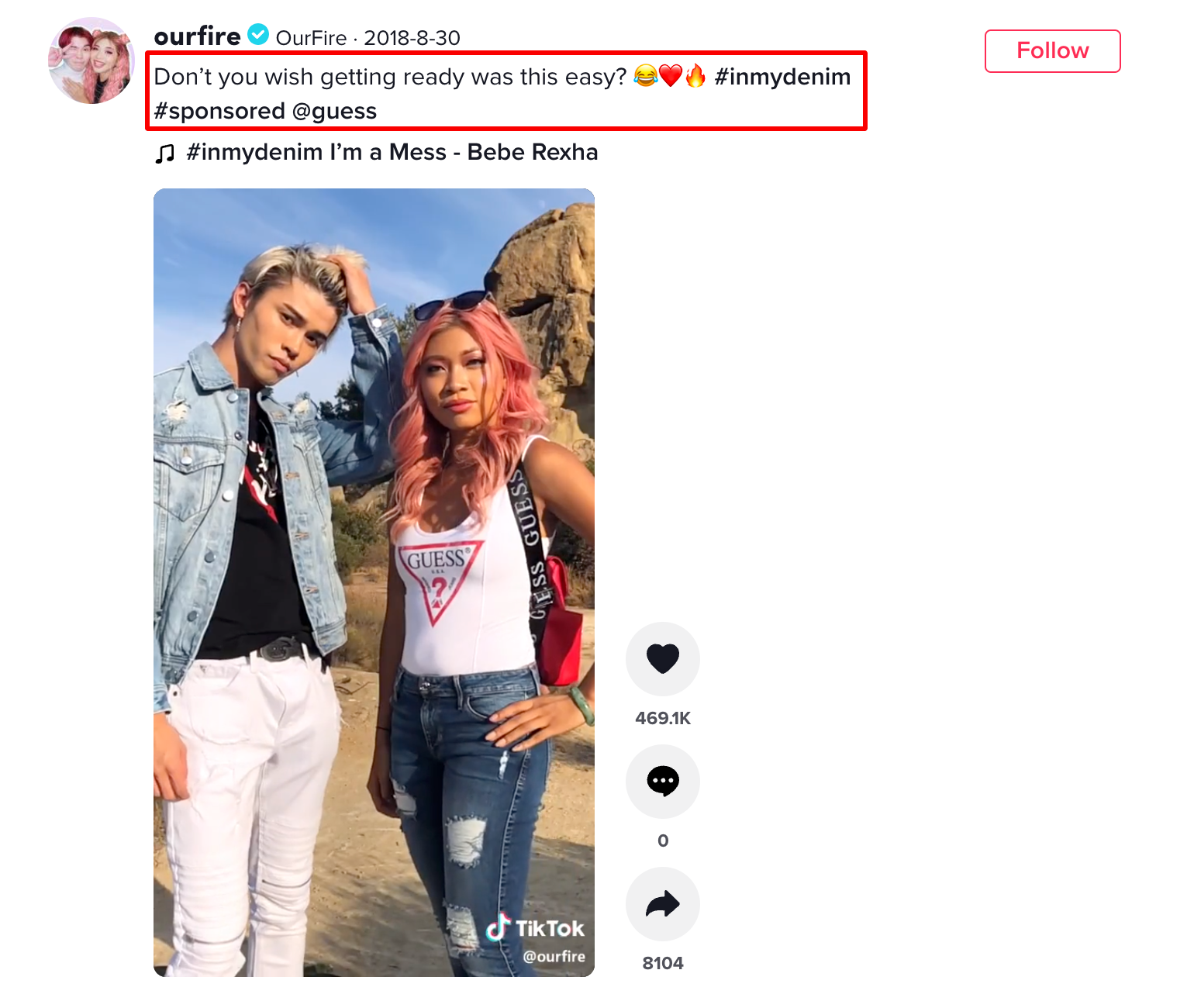

Advertising and Visual Analysis

We’ve mentioned advertisements a couple of times, but now let’s shift our focus specifically to images designed to sell a product, idea, or service. Advertisements come in a variety of formats. Traditionally, they would be presented as print advertisements or commercials. Print advertisements would appear in print publications, such as magazines and newspapers, or as billboards or posters; basically, print publications were a static combination of words and images designed to catch the consumer’s eye. In addition to print advertisements, commercials were prevalent and would appear as a 30 second (or more) video shown in between segments of a television program.

Advertisements still appear in these traditional formats; however, with the advent of streaming services and social media and the decline of print publications, they began to exist as sharable videos and meme-like images on social media, or as videos or pictures webpages and more.

19 Basic Appeals in Advertising

In 1982, Jib Fowles, a professor and author, wrote an article titled “Advertising’s Fifteen Basic Appeals.” Fowles believed advertisers appealed to consumers’ basic sociological, cultural, physical, and emotional needs. Building on this idea, we have incorporated four additional needs to form a list of 19 basic appeals.

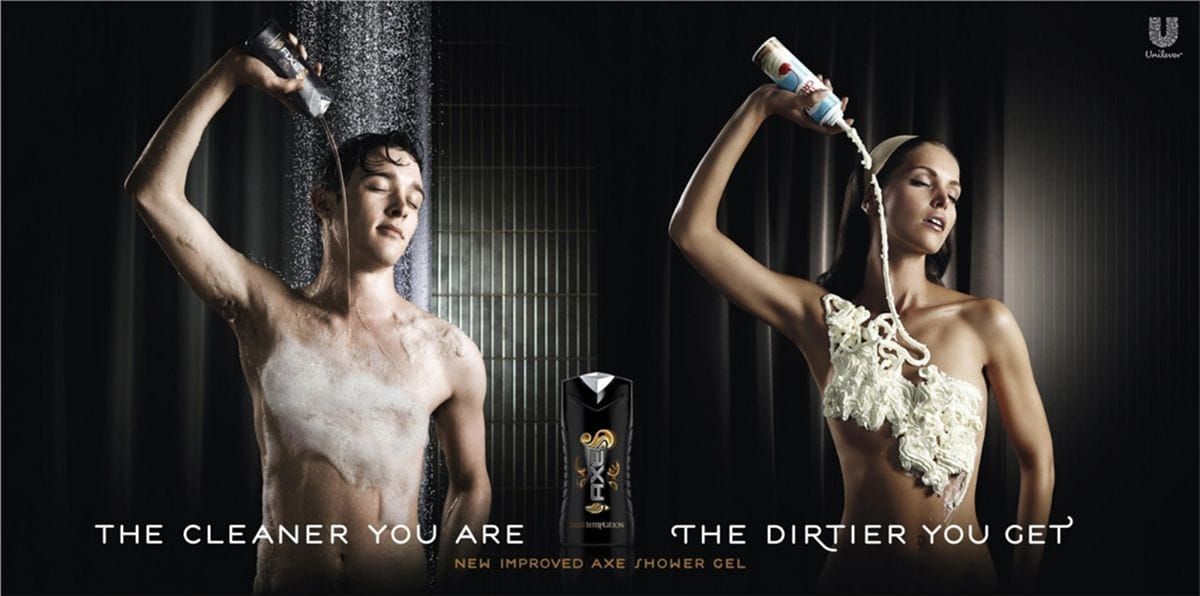

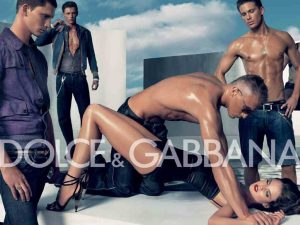

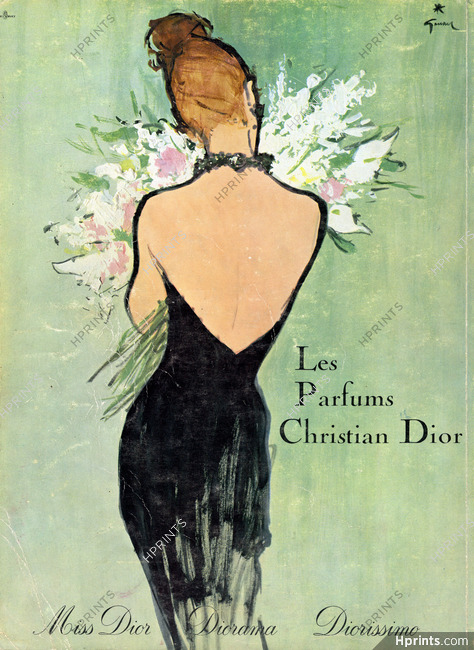

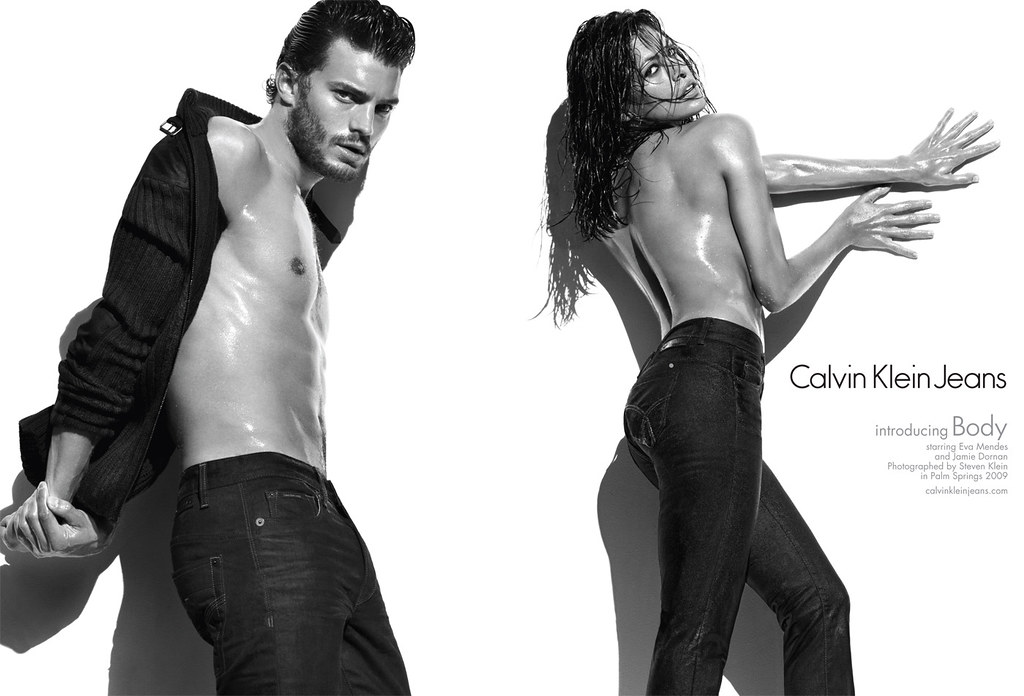

1. The Need for Sex (Fowles)

Provocative images are rampant in advertising and easy to spot. These images focus on sexualized language and images.

Figure 14.7 Ads and the Need for Sex

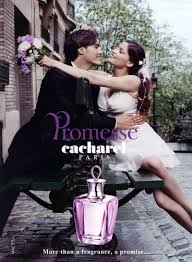

2. Need for Affiliation and/or Affection (Fowles)

This appeal is the softer version of the appeal to the need for sex. It usually involves a romantic tone and or setting in the ad and is selling, indeed a promise for sex, but not lustful sex: loving sex. Women (or anyone considered “feminine”) are the most susceptible to this type of appeal.

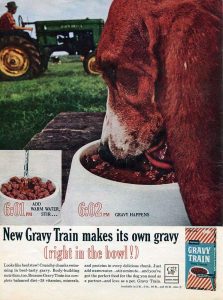

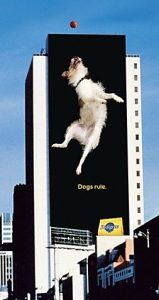

3. Need to Nurture (Fowles)

Ads that use this appeal are generally focused on consumers’ need to protect those in their care, such as children and pets.

Figure 14.9 Ads and the Needs to Nurture

4. Need for Guidance (Fowles)

This can also be considered the need to be nurtured. Consumers want someone to tell them how to navigate the tricky world in which we live, so the need for guidance answers that call.

Figure 14.10 Ads and the Need for Guidance

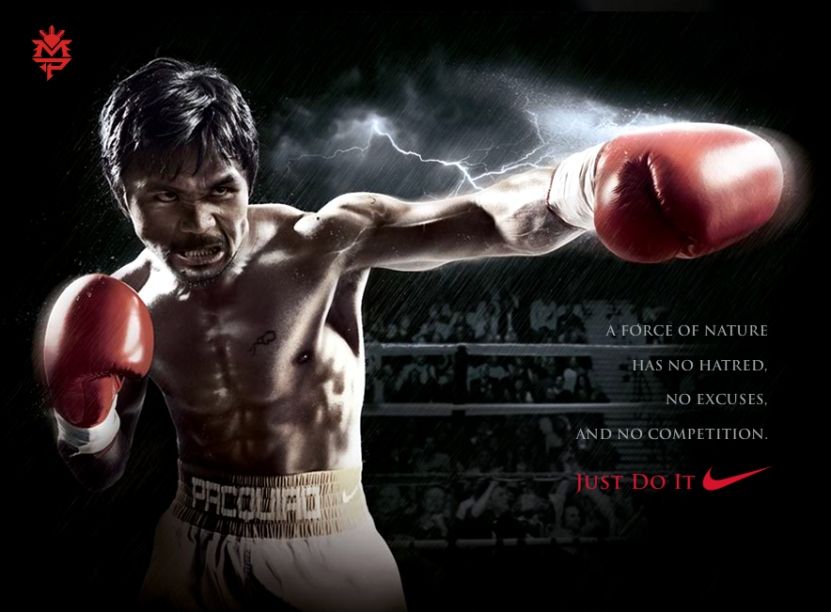

5. Need to Aggress (Fowles)

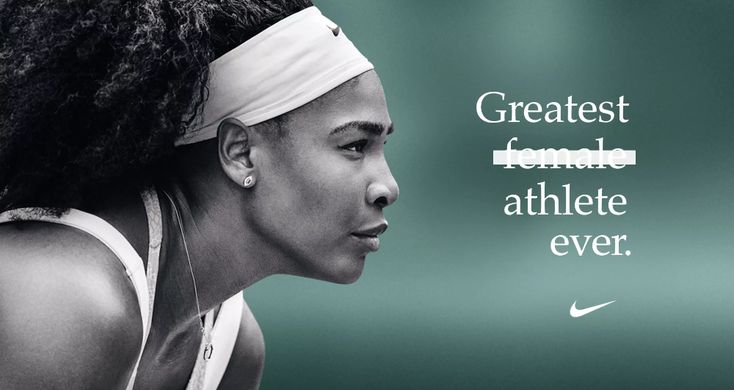

This need harnesses the aggression that society usually encourages consumers to suppress, but in the ad, it is used in a socially acceptable manner, such as the Nike ad of the boxer or the ad for Old Spice shown below.

Figure 14.11 Figure Ads and the Need to Aggress

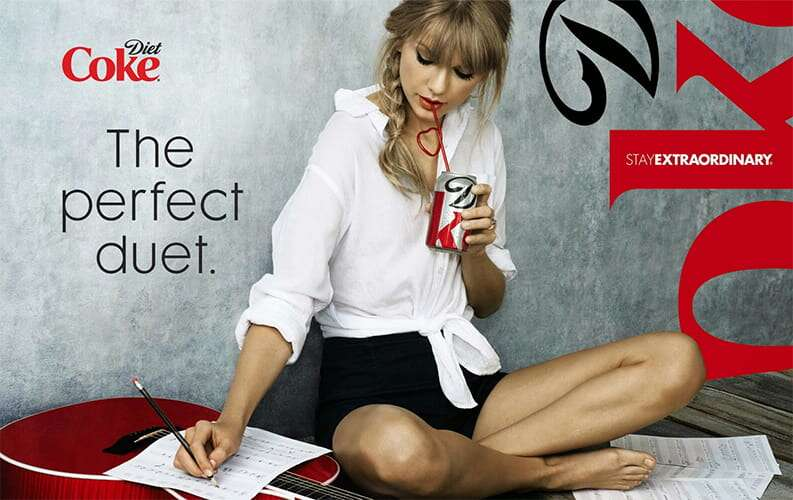

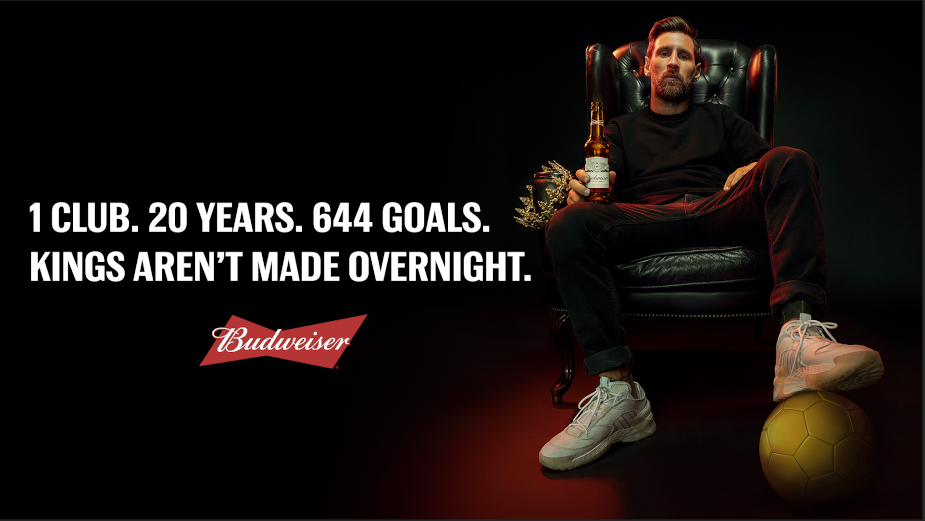

6. Need to Achieve/Be Successful (Fowles)

Advertisers count on our wanting to purchase products that make us appear “rich” and “successful,” even if we are not. Interestingly, in recent years, celebrities also endorse more mundane items (like milk).

Figure 14.12 Ads and the Need to Achieve

7. Need to Dominate (Fowles)

“Dominance” means “power exerted over others,” so this appeal is all about power and control. For many years, this appeal was associated with men in high-power positions, such as corporate CEOs. However, this appeal is no longer limited to masculinity as roles for men and women have changed over the last 50 years. Women and men in ads are now also shown in dominant roles, though the roles are usually sexual in nature and the power is fleeting.

8. Need for Prominence (Fowles)

This appeals to consumers’ desire for status symbols, i.e., symbols of wealth and success. Companies like Coach and Versace (and others) have created a brand awareness that demands attention – people notice when someone has a $500 purse or a $2000 watch. While you may not be a celebrity, you can at least look like one (or, even better, be mistaken for one).

Figure 14.14 Ads and the Need for Prominence

9. Need for Attention (Fowles)

In a world dominated by selfies and social media (both of which promote a “look at me” attitude), this appeal has become commonplace.

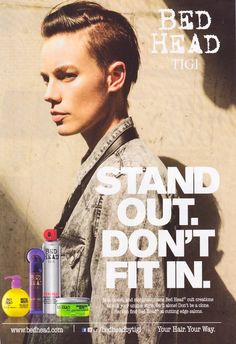

10. Need for Autonomy (Fowles)

This appeal speaks to the need to stand out and be seen as an individual, to be treated as independent and recognized as such.

Figure 14.16 Ads and the Need for Autonomy

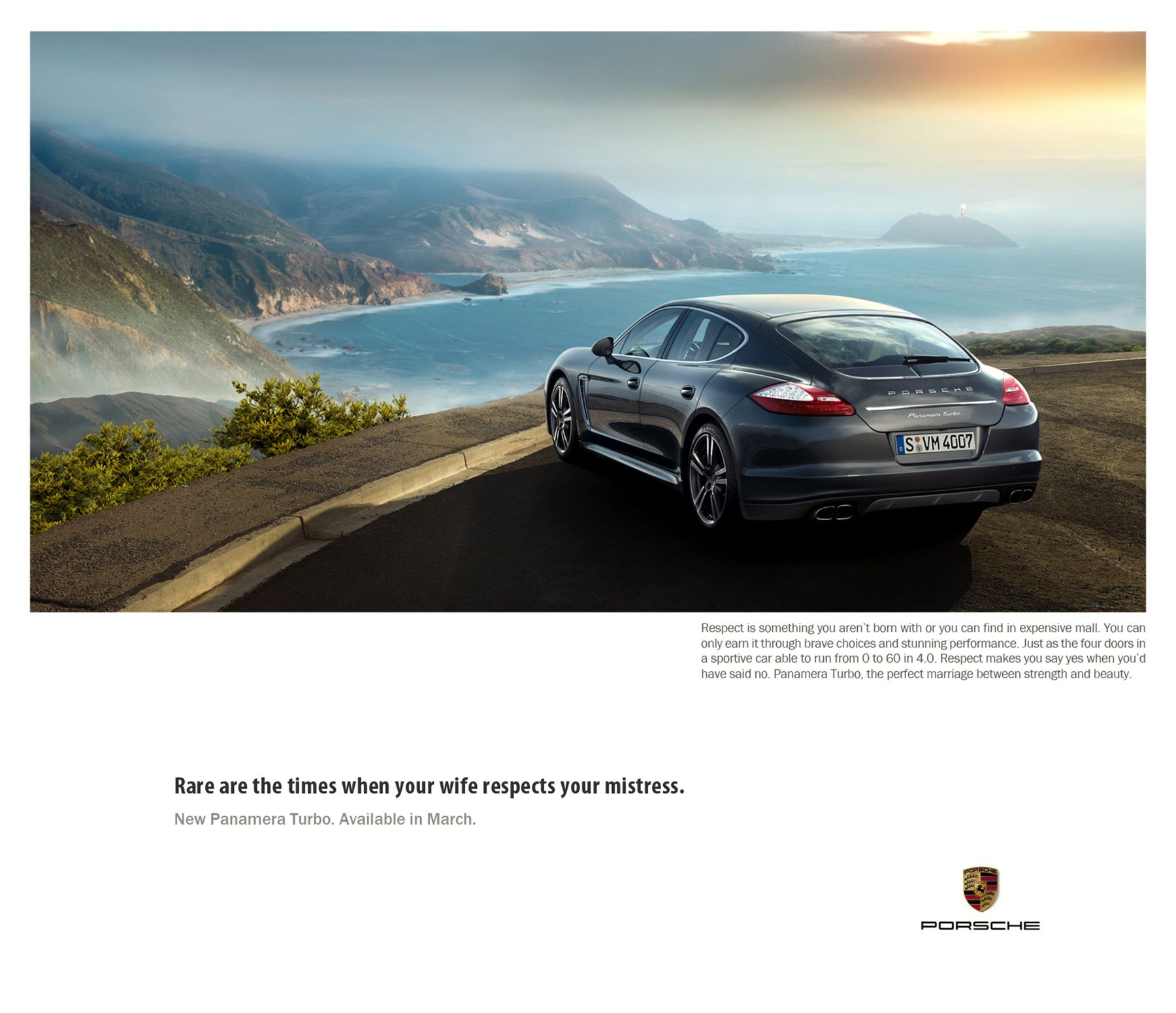

11. Need to Escape (Fowles)

The need to escape invokes a desire to leave the everyday life behind.

Figure 14.17 Ads and the Need to Escape

In the Porsche example above, the tagline claims “Rare are the times when your wife respects your mistress,” so there’s an extra dose of escaping the mundane.

In the Porsche example above, the tagline claims “Rare are the times when your wife respects your mistress,” so there’s an extra dose of escaping the mundane.

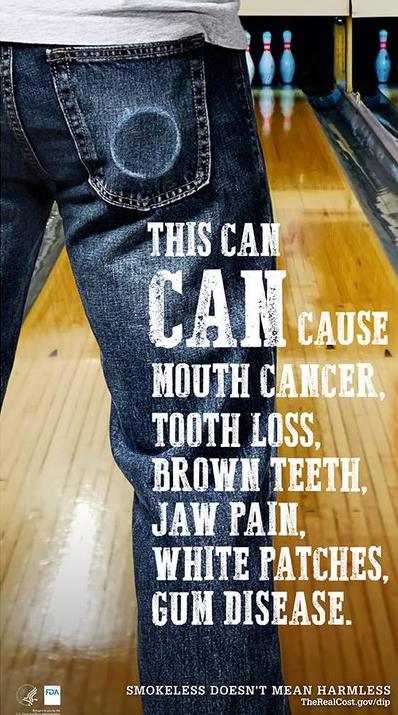

12. Need to Feel Safe (or Appeal to Fear) (Fowles)

The basic human desires include the need to feel safe and secure. Advertisers exploit this by “threatening” or scaring people into thinking terrible things will or can happen if their product is not purchased.

Features 14.18 Ads and the Need to Feel Safe

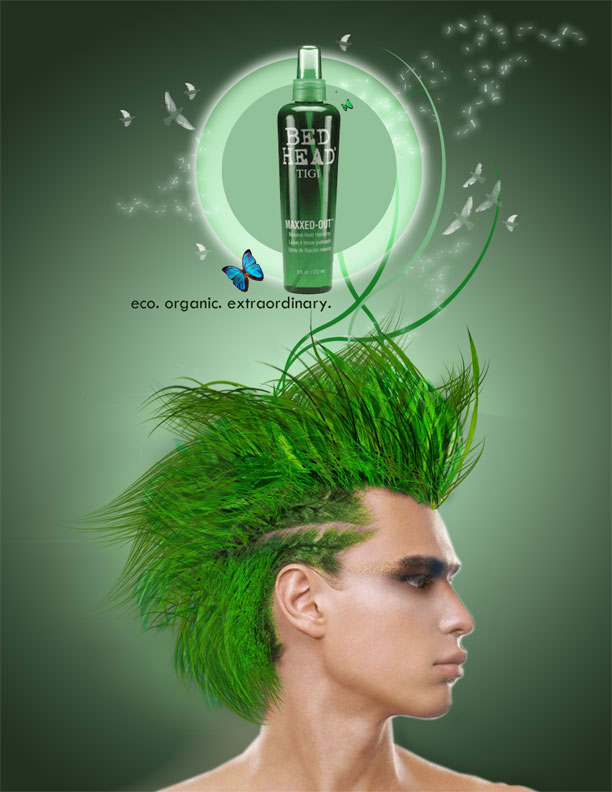

13. Need for Aesthetic Sensations (Fowles)

Images have the power to inspire emotions simply by being beautifully constructed. Perfect symmetry, lighting, setting, colors, and artistry can achieve the goal of catching the eye of the consumer.

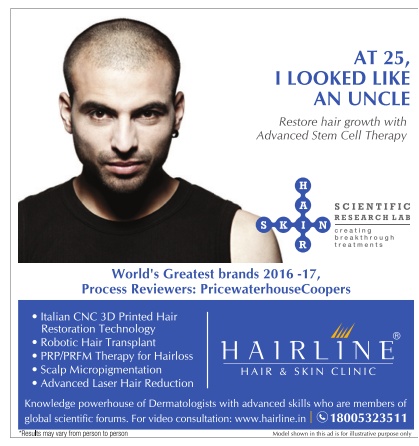

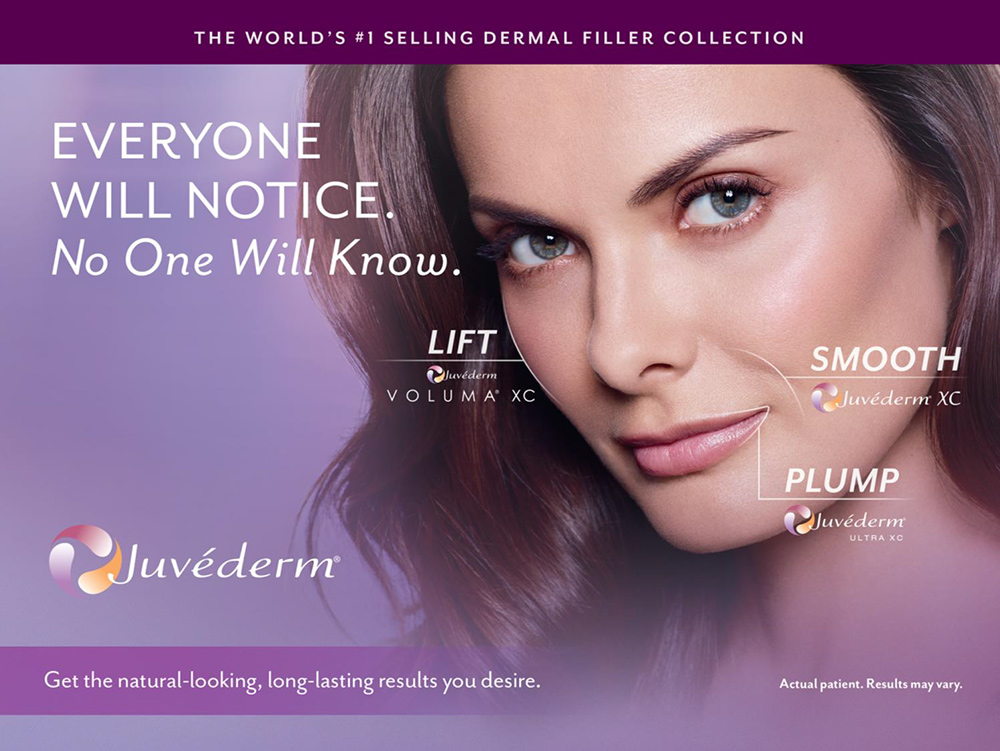

14. Need for Aesthetic Perfection

For the human aspect of this appeal, beauty and images of what is beautiful abound in advertising. The appeal works because consumers feel that if they purchase the product, they too will achieve “perfection.” This, of course, is impossible. You will hardly ever see “ordinary” looking people selling the ideal of beauty, unless it is as a “before” model in an ad for plastic surgery or weight loss. Most ads that feature people in them use the need for aesthetic perfection.

Figure 14.20 Ads for the Need for Aesthetic Perfection

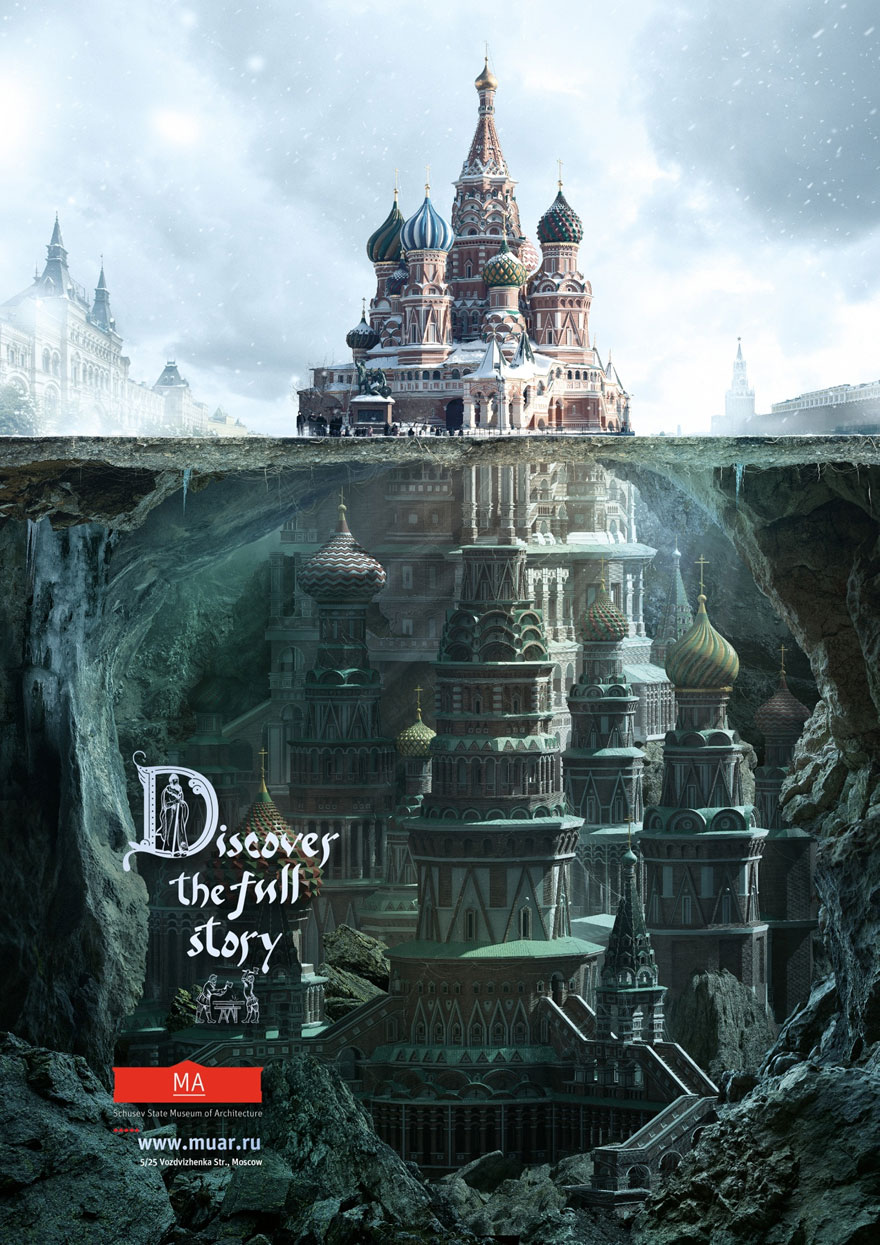

15. Need to Satisfy Curiosity (Fowles)

We are curious by nature, and in the modern era, we are used to that curiosity being instantly satisfied (#google). Ads that use questions to get our attention use the need to satisfy curiosity.

Figure 14.21 Ads for the Need to Satisfy Curiosity

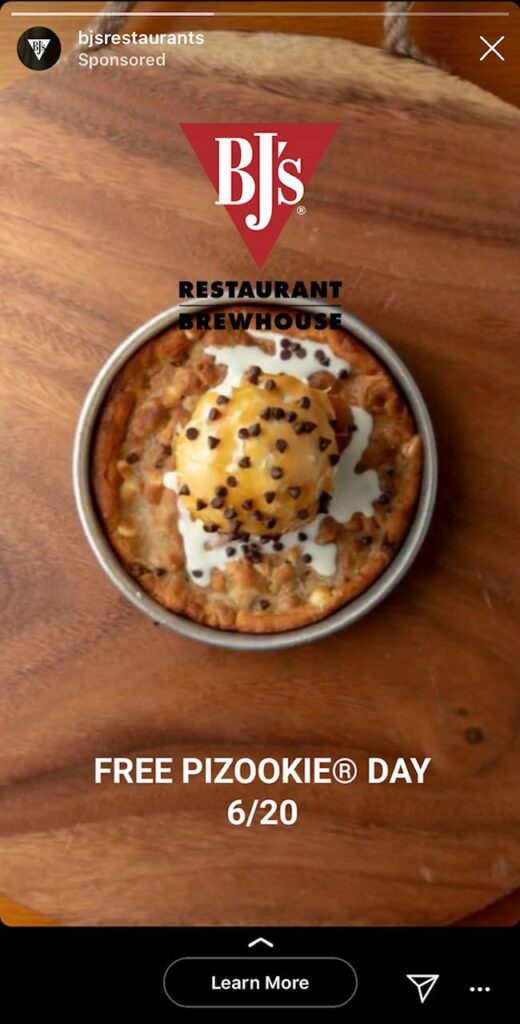

16. Physiological Needs (Fowles)

16. Physiological Needs (Fowles)

There is a difference between “needing” and “wanting,” though advertisements have worked hard to blur that line. Humans have certain physiological needs, such as eating, sleeping, and having shelter. Advertisers are clever to appeal to such needs—if you’re going to have to eat anyway, you might as well eat something delicious; if you’re going to have to sleep, you might as well sleep on the best mattress, etc.

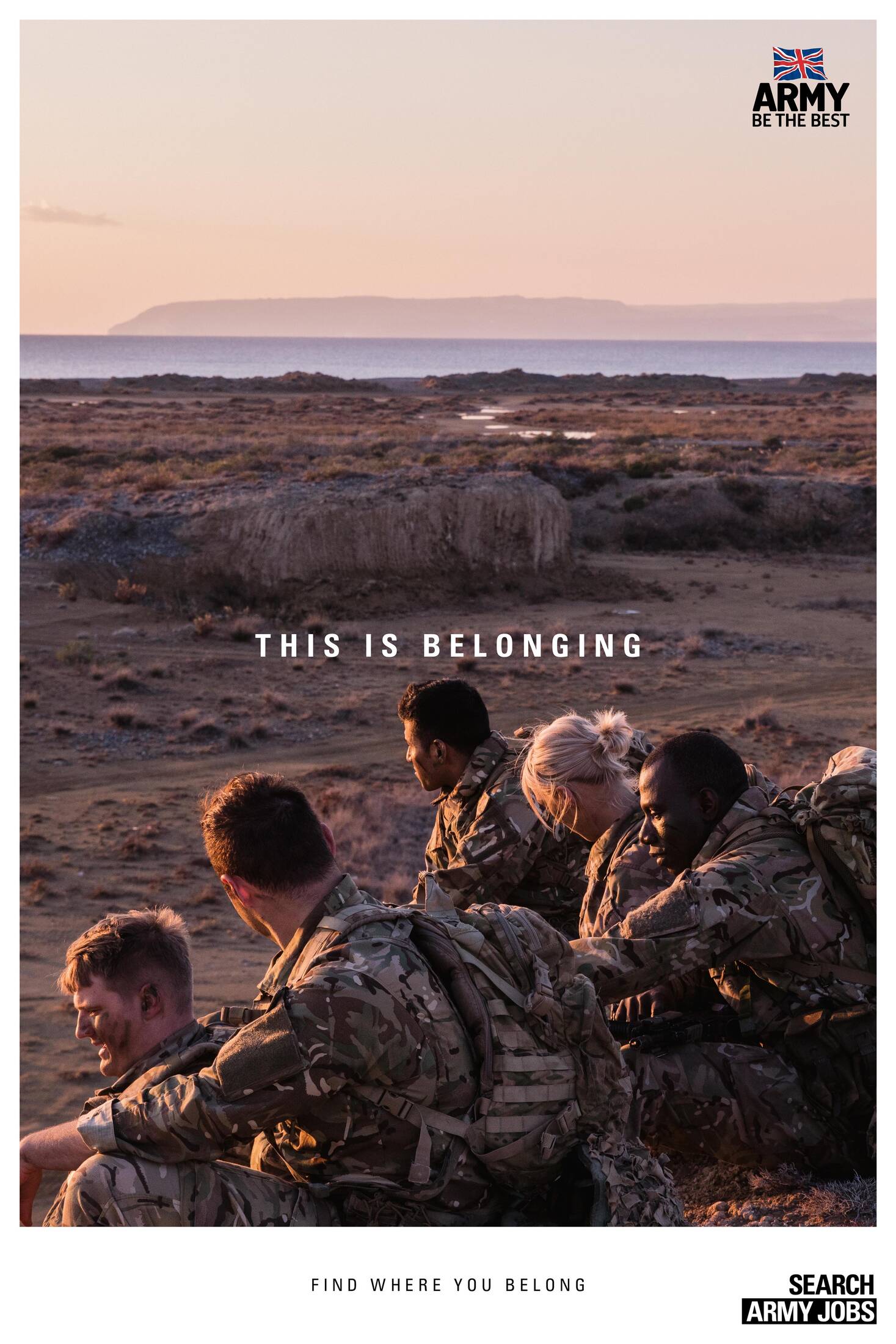

17. The Need to Belong

Also called bandwagon, this appeal draws on our need to be a part of the group. As humans we desire to belong and feel camaraderie with others who like the same things we do. This kind of appeal is often seen in cigarette and alcohol ads where the message is a not so subtle, “everyone’s doing it.”

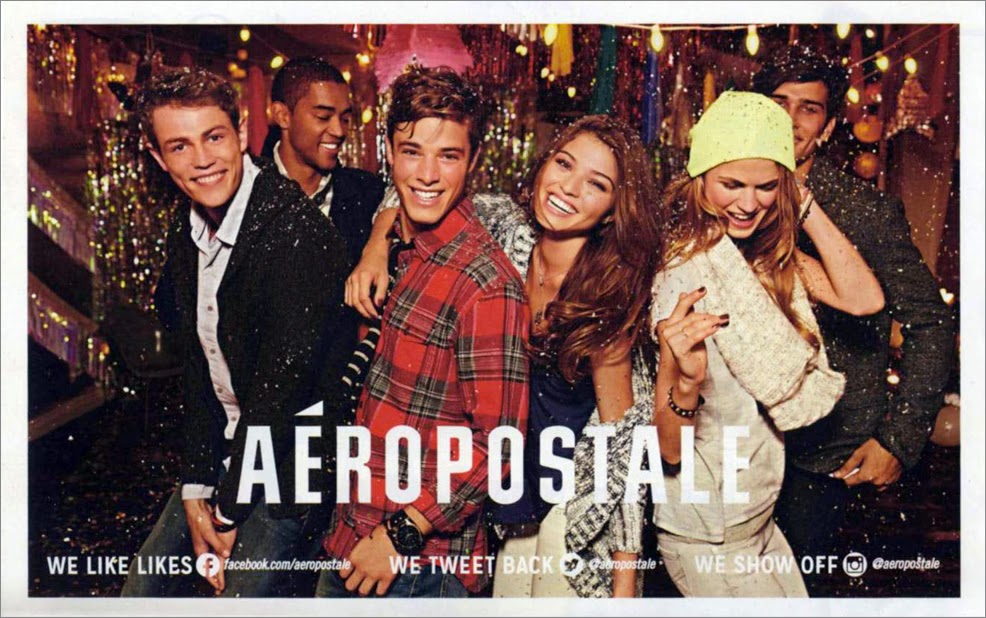

Figure 14.23 Ads and the Need to Belong

18. The Need to Help the Helpless

Also called the appeal to our compassion, this appeal targets our need to help the most helpless members of our society, such as children, pets, the elderly, differently abled, etc. This appeal is also often in PSAs (Public Service Announcements, which are not ads; ads sell products; PSAs offer advice or suggestions or ask for donations to a cause). Many ads use multiple appeals, so the same Life Alert ad that demonstrates the need for safety can also represent the need to help the helpless.

Figure 14.24 Ads and the Need to Help the Helpless

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPVGVN8kwKk

19. The Need for Victory

Winning equals success and many sporting goods and shoe manufacturers count on you purchasing their products with the understanding that if you do so, you will be a better runner, jumper, etc. Nike commercials are notorious for banking on the images of superstar athletes in order to appeal to your need to improve your own performance: “Everyone wants to be like Mike.” And if you wear Air Jordans, you too can fly. These ads also promote winning at any cost, or price.

Rhetorical Appeals and Advertisements

Aristotle’s rhetorical appeals of logos, pathos, and ethos can also apply to the persuasion inherent in advertisements.

Pathos

Ethos

Analyzing Images for Advertising Appeals and Rhetorical Appeals

Analyzing Images for Advertising Appeals and Rhetorical Appeals

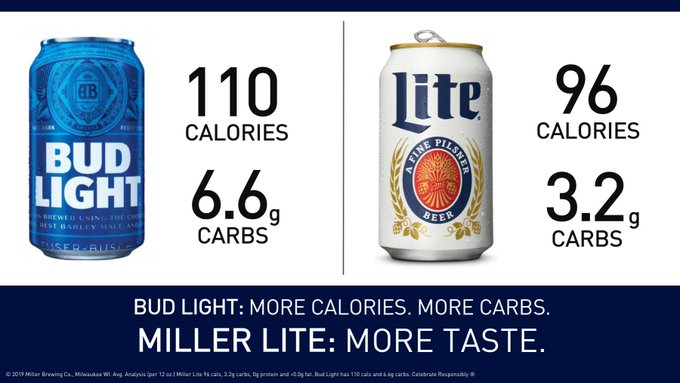

All advertising, whether it be print advertising or ads you see on social media, uses emotional appeals. Most ads use a combination of appeals: for example, the appeal to the need for sex combined with the appeal to the need to belong. In another example, an appeal to the need to nurture might also be combined with an appeal to logos.

When analyzing advertising, look closely at all aspects of the ad: the colors used, the written words, the product placement, the models used, and any other aspect such as camera angles that speak to the underlying message the ad is sending. The obvious, explicit message is always, “Buy this product.” The hidden and more subversive (implicit) message is “Buy this product because . . .” and reasons include concepts being sold. This is why the images in ads are often large and the product name is small (sometimes, a specific product is not even mentioned). Companies sell concepts; if you buy into the concept, you are more likely to buy the product.

Common concepts being sold in ads:

- Gender roles

- Gender identity

- Beauty standards

- Sexiness

- Adventure

- Youth

- Americanness

- Peer pressure

- A particular lifestyle (often a high class or exciting one)

- Comfort

- Uniqueness

- Fitting in

- Standing out

- Fame and fortune

- Popularity

Exercises

Choose one of the following ads and

- Establish who the target audience (demographic) is—be as specific as possible (consider age, race, socioeconomic status, gender, lifestyle, etc.).

- Explain two emotional appeals (from the list of 19 emotional appeals) being used.

- List two other elements being used (color, font, juxtaposition, light, etc.).

Questions to Consider for Visual Analysis

- What is the rhetorical situation (audience, context, content, genre, and author)?

- What general impression do you have of the visual (is it eye catching, funny, offbeat)? What is the central focal point? Does it immediately attract your attention?

- Does color contribute to the purpose/effect? How does color create the mood of the visual? Do the colors function symbolically or exist more to draw the viewer’s attention to an intended focus?

- How do these design elements work together to express meaning? What kind of imagery is used, along with color and font? How are images and words working together? (Consider the five basic principles of composition.)

- What is the social or cultural context of the image? How is it linked to the message and/or purpose? What historical events were occurring that may have influenced the creation of a text? Does the image continue to circulate over time and continue to play a role in the production of culture?

- Does the design play a role in the message? For example, does either the background or foreground contribute more or less to the message? Is there an obvious omission of anything one would normally expect in such an ad?

- What figures appear in the visual text? Can you identify their age, ethnicity, social class, and profession? Do any of these elements contribute to the visual’s meaning?

- Does the visual text reflect stereotypes about race, gender, etc.?

- Do the figures’ facial expressions or appearance suggest interpretations consistent with the apparent message of the visual text? Does the image express the meaning better than words could?

- Does the image suggest what scene preceded the moment captured in the photo? Of what followed?

- What is your general impression of the message conveyed by the visual? Does any bias seem apparent in the image? Is there a caption? If so, does it effectively add to or help explain the image?

- What rhetorical appeals (logos, pathos, ethos) and advertising appeals are present in the visual text?

- What is the prevailing tone of the image? Is it consistent with the intended message?

Exercise

Analysis of an advertisement

Thoughts: Advertising is one form of written communication. It often attempts to appeal to our emotions, both physically and mentally (i.e., physical: think of the “soft leather interior” of that new Lexus; mental: imagine relaxing on a cruise ship). Like all texts, advertisements often work on multiple levels. Advertisers often use symbols, metaphors, clichés, and emotions (to name only a few), to appeal to a specific audience. An ad may be showing you one thing, but advertisers are hoping that you’re thinking of something else (i.e., surface level: “Drink our beer, it tastes great”; implied level: “Drink our beer and you’ll be attractive men with a better chance of attracting beautiful women.”)

Rhetorical analysis of visual texts: “Just as with verbal texts, we need to understand how visual texts [like ads] work in rhetorical ways to achieve particular purposes and how they work to convey meanings that relate to the context in which they are realized” (Rhetoric). You will be closely “reading” an ad to discover how it attempts (or succeeds) to persuade its target audience.

Prompt:

Using “19 Basic Appeals in Advertising,” from Ch. 13, analyze the emotional appeals featured in one print advertisement of your choice.

Your ad:

- May be from a magazine

- May be from a Google search (search brands like Dolce & Gabbana, Calvin Klein, Carl’s, Jr., Toyota, Porsche, etc. OR search by topic: “make-up ads,” “muscle ads,” “controversial ads,” “clothing ads,” etc.

- Must be a MODERN ad (ads sell products).

- Should NOT be a PSA (PSAs do not sell products; they offer advice or suggestions. They may ask a viewer to send money to a cause (like the ASPCA or Feeding America), but no product is received in exchange).

________________________

Misc:

- Structure: introduction with thesis; body paragraphs; conclusion. The ad needs to be included (copy/pasted onto the last page of the essay).

- The thesis needs to include the implicit message of the ad and the emotional appeals used by the ad (use no more than three emotional appeals).

- Sample thesis: The ad for Cover Girl Long-Lasting Lipstick uses appeal to the need to achieve, the need for sex, and appeal to aesthetic perfection in order to make women feel obligated to purchase their product to fit into society. The ad also uses specific colors and word choice to manipulate the audience.

- Once you have analyzed the ad according to the emotional appeals, you may also include other appeals that may not fit under the list (use of color, word choice, organization, balance, juxtaposition, light, repetition, use of clichés, or figurative language, etc.)

- You must establish the target audience in the first or second paragraph and explain how you know who the target audience is.

- Your last body paragraph or the conclusion should include whether or not the ad is effective for the target audience.

Specifics:

- 2.5-3 pages

- Use MLA format: double spaced, Times New Roman, 12 pt. font

- The essay should be written in third person academic voice (avoid “I” or “you”).

Student Example 1: Riana Saint Rhetorical Analysis of an Ad Essay

Student Example 2: Max Suarez Rhetorical Analysis of an Ad Essay

Key Takeaways

- Advertisements come in a variety of formats, including traditional ones (print advertisements in magazines, newspapers, billboards, posters, and TV commercials) and modern ones (sharable videos, meme-like images on social media, web page ads, in-game ads, YouTube/Twitch ads, and influencer partnerships).

- The rise of social media, DVRs, and the decline of print have shifted advertising methods. Advertisers now utilize social media influencers and integrate ads into various digital platforms. Future trends may involve AI and deepfakes, necessitating critical consumer awareness.

- Despite changes in formats, advertisements continue to use traditional persuasive techniques to appeal to broad demographics. Common strategies include recognizable symbols, gender roles, and stereotypes.

- Advertisements target basic sociological, cultural, physical, and emotional needs. Jib Fowles’ “Fifteen Basic Appeals” expanded to 19 appeals, including needs for sex, affiliation, nurture, guidance, aggression, achievement, dominance, prominence, attention, autonomy, escape, safety, aesthetic sensations, aesthetic perfection, curiosity, physiological needs, belonging, helping the helpless, and victory.

- Advertisements also employ Aristotle’s rhetorical appeals: logos (logic), pathos (emotion), and ethos (credibility).

- Effective ads often combine multiple appeals, blending emotional and logical elements.

- In analyzing ads, look at colors, words, product placement, models, camera angles, and implicit messages.

- Ads sell concepts (e.g., beauty, youth, adventure, popularity) as well as products, including gender roles and beauty standards among others.

- Understanding these key elements enhances critical thinking about the persuasive techniques used in advertising and the evolving landscape of media consumption.

Attributions

Writing Guide with Handbook by Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image Credits

Figure 14.1: “Chaddanta Jataja Amaravati” by Vidya Dehejia on Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC0

Figure 14.2: “DSCF1343” by K. Kendall, Portland, OR, USA on Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Figure 14.3: “Kodak Digital Waterfall” by Nan Palmero on Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Colored pencils Image by Bruno from Pixabay

“Flag of Mississippi (1894–1906)” by Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain

Current “Flag of Mississippi” by Rocky Vaughan, et al./Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain

Woman Sitting on Ottoman in Front of Three Paintings Photo by Una Laurencic on Pexels

Street Lights by Jose Francisco Fernandez Saura on Pexels

Megan Rapino for Nike Photo by Nelson Ndongala on Unsplash