Chapter 6: Drafting

What is Drafting?

After you give your ideas some structure by crafting a working thesis statement and an outline, you may move on to the drafting stage. Drafting builds on the structuring work you did in the last chapter, and most writers draft in pieces, putting together paragraphs as they are ready to and revising paragraphs as they write more. There is no one correct way to draft, and you will develop your own methods as you understand what works best for you.

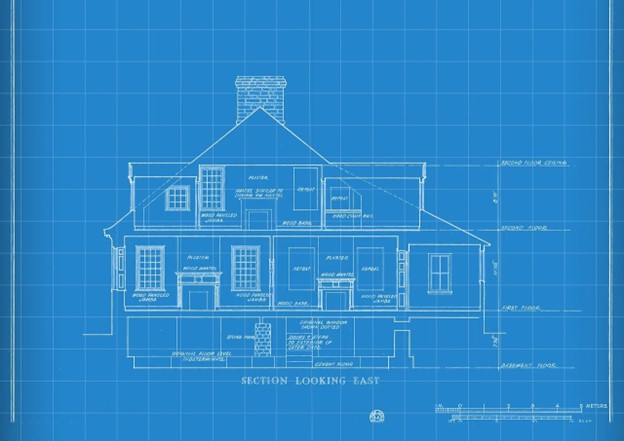

You may think of drafting as a blueprint for the final project. It is important to start with a foundation and build from there.

You may think of drafting as a blueprint for the final project. It is important to start with a foundation and build from there.

The following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. The first draft’s purpose is to get ideas down on paper that can then be revised. Consider beginning with the body paragraphs and drafting the introduction and conclusion later. You can start with the third point in your outline if ideas come easily to mind, or you can start with the first or second point. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. If you cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest, but do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you tell yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can for the particular audience you have in mind. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to know to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas, so they are meaningful and memorable and your communication is effective?

- Write knowing that the revision and editing processes lie ahead and leave plenty of time for those stages. Don’t worry about your writing being perfect – that will come later in the writing process.

The following sections will provide specific writing strategies you can use while crafting your introduction, body paragraphs, transitions, conclusion, and the title.

The Introduction

When someone is first introduced to another person in a formal social situation or in the professional world, the two people typically shake hands, exchange names, and make eye contact. Someone may also smile or share additional information to help the other person remember him/her/them. When introducing yourself, the idea is to make a personal connection, to be memorable, and to interest others.

When someone is first introduced to another person in a formal social situation or in the professional world, the two people typically shake hands, exchange names, and make eye contact. Someone may also smile or share additional information to help the other person remember him/her/them. When introducing yourself, the idea is to make a personal connection, to be memorable, and to interest others.

An essay introduction is similar; the writer needs to connect with his or her audience, or at the very least, tempt the reader to continue. The writer may share some additional information in the introduction to help the reader understand the topic and to provide expectations about what will be covered, suggested, or solved in the piece of writing.

A typical introduction will have three main elements:

The hook. The first few sentences of the essay set the scene and grab the reader’s attention.

Background information. In this section, the writer identifies and explains the question or problem that the essay addresses and provides any needed background information, such as the definition of key terms, summary of events leading up to the problem, or factual details needed for explaining the context of the problem.

Thesis statement. The thesis provides readers with a map of your argument.

Introductory Techniques

When attempting to “hook” the reader, a writer may use seven typical introductory techniques. They include:

- Funnel

- Questions

- Startling statement/surprise statistic

- Quote

- Anecdote

- Background information

- Turnabout

Funnel

This technique begins with a broad, general statement and then becomes narrower and narrower, funneling down to the thesis.

Example of Funnel Technique

More and more people are concerned about their health. All over America, people are trying to reduce stress, get enough sleep, exercise more, eat healthier, and lose weight. When attempting to lose weight, people have a number of diets to choose from, such as Atkins, South Beach, and The Zone, but there is another diet—or rather a lifestyle—people should consider. Vegetarianism. This lifestyle not only helps people lose pounds and maintain a healthy weight, but going vegetarian also has a number of other added health benefits that often are not as obvious but make a positive difference in one’s overall health.

Questions

This technique uses questions to engage the reader in the topic. One question does not provide enough development, so three questions is a general rule that typically works best. The writer should be sure to answer the questions in the body of the essay or address any unanswered questions in the conclusion. The writer should try to avoid putting questions in second person.

Example of Questions Technique

Is it possible for students to be successful in school without being aware of their intellectual strengths and weaknesses? Do students know how important it is to recognize their own abilities? Are they able to use their various types of intelligences in order to understand what they need to study? To me, achieving academic goals are nearly impossible without recognizing one’s strengths. The three strongest abilities I possess are spatial, interpersonal, and linguistic intelligence and using these three help me survive in the academic jungle.

Startling statement/surprise statistic

Starting with one (or more) unusual statement or a surprising statistic is another way a writer can capture his audience. With an intriguing beginning, readers want to know more and thus continue to read. When sharing facts, dates, statistics, etc., a writer should try to avoid “It was/There were” type of statements that tell about a situation rather than show it.

A poor example would be as follows: It was November 13, 2015. A horrible event shocked the world.

Instead, this revised statement gets more attention: “150 Dead in Paris,” read the headlines from The Guardian on November 14, 2015, the day after the grisly Paris bombings.

Example of Startling Statement/Statistic Technique

In America, twenty-four people per minute are stalked, physically or emotionally abused, or raped. Though men can be raped and do experience domestic violence, women are still disproportionally affected. Three out of every ten women will be victims of domestic violence or rape, and the perpetrator is generally a repeat offender, often moving from one partner to another, using the same tactics. Despite ongoing mental and emotional abuse, on average, it takes a woman seven times of leaving her partner before she will actually leave her partner permanently. The National Domestic Violence Hotlines has done well in trying to raise awareness of partner abuse, and now more of the general public, not just law enforcement and social workers, better understand such dismaying statistics. What might not be as well known, though, is why domestic violence is so prevalent in our society. Although there are many reasons why we are a nation that accepts violence among intimate partners, the biggest reason is that we are a culture that remains incredibly sexist.

Quotation

Beginning an essay with a quote is another effective way of interesting readers in a topic. Quotes can be from books, movies, famous sayings, an expert on the essay topic, or comments from a friend or relative. When using this technique, the writer needs to cite the source and include an in-text citation of where the quote was published unless the writer is quoting a phrase that a family member or friend typically says such as, “My father always said, ‘Homework first, play second’” or a general, cultural maximum such as “A stitch in time saves nine.” The writer must connect the quote to the larger topic; the quote is a way to get into the subject matter.

Example of Quotation Technique

According to Kabalarian Philosophy webpage “The power of a name and its value has long been immortalized in prose, poetry, and religious ceremony. Everyone recognizes himself or herself by name” (“What’s”). While Kabalarian philosophy supposedly sees a connection between numbers and symbols to help create an understanding of the meaning of one’s name, most people would agree that a person’s name is one of the most important things about a person. A name is one’s identity, and unlike a shirt, we can’t change it to whatever we feel like each day. Our name tells people who we are and where we come from. Whether our name is religion based, passed down from our parents, or a randomly chosen name, it always has meaning and a backstory behind it. Although other people have various and unique reasons for appreciating their name, I believe my full name represents my diversity, my heritage, and my unique individuality. – Written by Shawn Villaescusa (adapted)

Anecdote (Story)

Starting an essay with an anecdote that the writer has experienced or heard about, as long as it related to the topic, can be a creative and personal way to broach a topic. Since this technique is essentially a narrative, the writer may use dialogue and a great deal of description. The anecdote may be humorous, sad, factual, etc. and may be written in third person, but is usually in first person point of view.

Examples of Anecdote Technique

Eve was once a straight “A” student. She had dreams of becoming the first black female president. Her view of the world was that women could be whatever they wanted to be until the day she was exposed to the modern day music genre called “rap.” For several weeks she listened to the rappers refer to her as “hoe” and “bitch.” She started to picture half naked women with oversized breasts and behinds described by these artists. All she wanted to do was fit in. So she changed her wardrobe. Grades no longer mattered to her; all she cared about was looking good and pleasing her boyfriend who dropped her once they slept together. She later became an employee at a local strip club. The young Eve who had dreams of becoming president was long gone. Instead, she would imitate black females in rap music videos, the women who were treated as a trophy or a random object. Although this story of Eve is fictional, it could be argued that many young black women’s lives end up like this because they listened to rap that contains this kind of misogyny. Rap music diminishes young black women’s worth enforcing false stereotypes and negatively impacts their relationships.

“Karen Marie! Come here now,” my mother boomed. Over thirty years later, I still remember how my mother’s voice echoed through the house like an angry clap of thunder. My calm, collected mother never raised her voice; usually all she did was raise an eye brow and I knew I was in trouble, so that afternoon when she called out both of my names, I knew my secretive actions had been discovered. I sauntered into the living room, ready to explain, to protest my ignorance, to lie. My mother pursed her lips and glared at me. This was the day I discovered how much my mother knew about me and how wise she really was.

Turnabout

The turnabout technique is used to stimulate surprise or controversy about a topic. The introduction begins by leaning toward one opinion and then “switches” to the opposite side in the thesis.

Examples of Turnabout Technique

War is terrible. Any war involves too much blood, physical destruction, emotional and mental costs—and of course, too many lives are lost. Wars are time consuming and incredibly expensive. Americans are exhausted and depleted given our fifteen plus years of involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq. War with radical Islamic rebels needs to be avoided at all costs; however, despite the costs and loss of lives, the fight against ISIS is absolutely justifiable and necessary.

Wars are necessary. Throughout history, people have fought to protect themselves, their families, countries, values, and ideals. In America, we have gone to war to protect others, fight for freedom, and stop military aggression. Despite the violent nature of ISIS, America’s involvement with ISIS radical militants is not necessary, and we should not get any further involved.

Here are a few final thoughts about developing effective introductions that a writer should consider. Generally, a well-developed paragraph is between five to seven or eight to twelve sentences long, depending on the level of the class, though an introduction may be a little shorter. A good writer will not simply begin with a technique like a quote or a question and then state the thesis. (Or perhaps they will, but then upon revision, they will develop the ideas so that the introductory technique leads smoothly to the thesis.) The sample below is one in which the writer has not taken enough time to delve into the topic of various types of intelligences before giving her opinion (thesis).

Poor Example

People differ in how they learn and what methods and strategies they use to learn. Our abilities may explain why some courses are easier for us than for others, and why we learn better from one instructor than another. For me, my three major abilities are logical-mathematical, spatial, and intrapersonal intelligence.

Background information

This technique is helpful when the writer needs to share historical, political, or cultural background information, definitions, or dates that the reader may need in order to more fully understand the topic. Generally, writers should avoid sharing personal history or dates since they probably are not relevant to most readers and may thus seem boring.

Examples of Background Information Technique

“We’ve always had reality television, always,” says Marc Berman of Mediaweek (Haggerty 13). Even before the birth of what is now known as reality television, there were reality shows like Candid Camera. This show, which appeared in the 1940s, was a show that captured reactions of real people in absurd situations: these situations were always introduced with the now famous tagline, “Smile! You’re on Candid Camera!” Long before American Idol debuted on our TV sets, viewers rooted for aspiring singers who sang in hope of becoming famous on the Original Amateur Hour. Shows such as Candid Camera and Original Amateur Hour marked the beginning of reality television. Reality TV took off when MTV launched The Real World in 1992. The term “reality TV” originated from The Real World, where “real” was used in the sense of “the world awaiting young people after they graduated from school” (“Reality”). Through the years, reality TV has become increasingly popular; undeniably, it is a success. Yet with success comes criticism, and reality TV is no exception. Critics have cited a number of reasons why this genre of entertainment is harmful. They cite that it plays on stereotyped personas and encourages going to extremes to achieve goals, which often results in physical, emotional, and mental stress. Despite the criticisms, reality TV is more than just entertainment and escape from the reality of day-to-day life; it also encourages and inspires viewers. – Written by Angelica Vinluan (adapted)

Narcocorridos, or drug ballads, are a subgenre of corridos, which is traditional narrative folk music with origins from Mexico. These ballads are very similar to the gangster rap and hip-hop subgenre of rap that is very popular in America. Although these drug ballads are considered a subgenre, in the last few decades they have blown up in popularity both in Mexico and in the southwest of United States and have now become mainstream and a cultural phenomenon, especially with the youth. Although the corrido genre of music is not new, with a lot of rich history and tradition hailing from the northern states of Mexico, the problem lies within this narco subgenre of corridos, which glorifies drug trafficking, violence, and the criminal lifestyle, and due to its vast popularity has the power to influence a lot of people. In a society where machismo is prevalent and a way of life, many young men of Mexican or Hispanic descent look up to and idolize the drug lords and traffickers and their lifestyle. The success and cultural acceptance of narcocorridos should be of rising concern due to its exaggerated portrayal of what it means to be masculine, or macho, which comes with numerous negative social implications and dangerous influences on young men.

Some introductory techniques may work better for certain types of essays. For example, the turnabout technique often works well for argumentative or persuasive essays. Most writers tend to use a few techniques regularly, but good writers experiment with multiple introductory types throughout a semester and try combining them. In fact, an ideal introduction often combines multiple techniques. It is also important to note that introductions may be more than one paragraph long, especially when the essays get longer and more complex in advanced writing and classes.

For additional ideas on how to write effective introductions and examples of which introductory strategies to avoid, please review the following handout:

The Body Paragraphs

The term body paragraph refers to any paragraph that appears between the introductory and concluding sections of an essay. Each body paragraph should support the claim made in the thesis statement by developing only one key supporting idea. This idea is often referred to as a discussion point.

Some discussion points will take more time to develop than others, so body paragraph length can and often should vary to maintain your reader’s interest. When constructing a body paragraph, the most important objectives are to stay on-topic and to fully develop your discussion point.

When constructing a body paragraph, limit beginning or ending with a quotation or a paraphrase. Rather, you should think of a body paragraph as conforming to the following pattern.

Typically, a body paragraph contains four main elements:

- a topic sentence,

- supporting evidence,

- an explanation of that evidence,

- a concluding sentence and/or transition.

Topic Sentences

A topic sentence is usually the first sentence of a body paragraph. The purpose of a topic sentence is to identify the topic of your paragraph and indicate the function of that paragraph in some way.

To create an effective topic sentence, you should do the following:

- Clearly identify the key idea or discussion point that you intend to expand upon in your new paragraph. When constructing a topic sentence, you may feel as though you are stating the obvious or being repetitive, but your readers will need this information to guide them to a thorough understanding of your ideas.

- Make a connection to the claim you make in your thesis statement. It might help to think of your topic sentence as a mini thesis statement. In your body paragraph, you should be expanding upon the claim you make in your thesis. For this reason, you should link your topic sentence to your thesis statement. Doing so tells your readers how this one point relates to the main thesis of the essay.

Exercise 6.1 – Writing Topic Sentences

The topic sentences have been removed from the following paragraphs. For each paragraph, write a suitable topic sentence. Make certain this topic sentence is broad enough to cover all the material in the paragraph.

Paragraph 1:

Some mathematicians work as computer scientists. Others work as statisticians for businesses or government agencies. Still others work in various areas of scientific study such as physics, chemistry, and even linguistics. Furthermore, mathematicians often work as teachers in high schools, colleges, and technical schools.

Paragraph 2:

First, gelato, which is Italian ice cream, contains less butterfat than American ice cream. Since butterfat masks flavor the way paraffin might, a low butterfat content is an advantage, not a disadvantage. Second, gelato has what people in the trade call a “low overrun.” Overrun is “the amount of air in the ice cream.” While gelato may contain as little as 5 percent air, which is 10 percent overrun, American ice cream is permitted to contain as much as 50 percent air, which is 100 percent overrun. Third, gelato is made from fresh, natural ingredients. Some inexpensive American ice creams contain ingredients such as the following: diethyl glucol, a substitute for eggs that is also used in paint removers; piperonal, a vanilla substitute that is also used to kill lice; and butraldehyde, a nut flavoring that is also an ingredient in rubber cement.

Paragraph 3:

Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ first instinct is to flee, not attack. Their fear of humans makes sense. Far more piranhas are eaten by people than people are eaten by piranhas. If the fish are well-fed, they won’t bite humans.

Paragraph 4:

According to Rachel Jones, Assistant Director of Housing Services, the initial purchase and installation of carpeting would cost $300 per room. Considering the number of rooms in the three residence halls, carpeting amounts to a substantial investment. Additionally, once the carpets are installed, the university would need to maintain them through the purchase of more vacuum cleaners and shampoo machines. This money would be better spent on other dorm improvements that would benefit more residents, such as expanded kitchen facilities and improved recreational space.

Supporting Evidence

Supporting your ideas effectively is essential to establishing your credibility as a writer, so you should choose your supporting evidence wisely and clearly explain it to your audience.

Types of support might include the following:

- Statistics and data

- Research studies and scholarship

- Hypothetical and real-life examples

- Historical facts

- Analogies

- Precedents

- Laws

- Case histories

- Expert testimonies or opinions

- Eye-witness accounts

- Applicable personal experiences or anecdotes

Providing Context for Supporting Evidence

Before introducing your supporting evidence, it may occasionally be necessary to provide some context for that information. You should assume that your audience has not read your source texts in their entirety, if at all, so including some background or connecting material between your topic sentence and supporting evidence is frequently essential.

The information contained in your evidence selection might need to be introduced, explained, or defined so that your supporting evidence is perfectly clear to an audience unfamiliar with the source material. For example, your supporting evidence might contain a reference to a concept or term that is not explained or defined in the excerpt or elsewhere in your essay. In this instance, you would need to provide some clarification for your audience. Anticipating your audience is particularly important when incorporating supporting evidence into your essay.

Now that we have a good idea what it means to develop support for the main ideas of your paragraphs, let’s talk about how to make sure that those supporting details are solid and convincing.

Good vs. Weak Support

When you’re developing paragraphs, you should already have a plan for your essay, at least at the most basic level. You know what your topic is, you have a working thesis, and you have at least a couple of supporting ideas in mind that will further develop and support your thesis. You need to make sure that the support that you develop for these ideas is solid. Understanding and appealing to your audience can also be helpful in determining what your readers will consider good support and what they’ll consider to be weak. Here are some tips on what to strive for and what to avoid when it comes to supporting evidence.

|

Good Support

|

Weak Support

|

Using Source Materials

When writing an essay that includes research, support your ideas with source materials. A research paper, by definition, makes use of source materials to make an argument. It is important to remember, however, that it is your paper, not what some professors may call a “research dump,” meaning that it is constructed by stringing together research information with a few transitions. Rather, you, as the author of the paper, carry the argument in your own words and use quotes and paraphrases from source materials to support your argument.

Learning how to use research purposefully in this manner is not an easy skill to develop. Expect it to take time and practice. Because this type of writing is the core of most academic writing, there is an entire section of the textbook devoted to research. For more detailed information on the relationship between research and your own ideas within the writing context, read Chapter 17.

The following are some useful strategies for writing strong paragraphs that integrate source material:

After you think you have completed enough research to construct a working thesis and begin writing your paper, collect all your materials in front of you (photocopies of articles, printouts of electronic sources, and books) and spend a few hours reading through the materials and making notes. Then, put all the notes and materials to the side and freewrite for a few minutes about what you can remember from your research that is important. Take this freewriting and make a rough outline of the main points you want to cover in your essay. Then you can go back to your notes and source materials to flesh out your outline.

Use quotations for the following three reasons:

- You want to “borrow” the ethos or credibility of the source. For example, if you are writing about stem cell research, you may want to quote from an authority such as Dr. James A. Thomson, whose ground-breaking research led to the first use of stem cells for research. Alternatively, if your source materials include the New England Journal of Medicine or another prestigious publication, it may be worth crediting a quote to that source.

- The material is so beautifully or succinctly written that it would lose its effectiveness if you reworded the material in your own words.

- You want to create a point of emphasis by quoting rather than paraphrasing. Otherwise, you probably want to paraphrase material from your sources, as quotes should be used sparingly. Often, writers quote source material in a first draft and then rewrite some of the quotes into paraphrases during the revision process.

Explaining Evidence

Remember not to conclude your body paragraph with supporting evidence. Rather than assuming that the evidence you have provided speaks for itself, it is important to explain why that evidence proves or supports the key idea you present in your topic sentence and (ultimately) the claim you make in your thesis statement.

This explanation can appear in one or more of the following forms:

- Analysis

- Evaluation

- Relevance or significance

- Comparison or contrast

- Cause and effect

- Refutation or concession

- Suggested action or conclusion

- Proposal of further study

- Personal reaction

You may use the following templates when explaining supporting evidence:

Basically, the author is warning that the proposed solution will only make the problem worse.

In other words, the author of the article believes that _____.

In making this comment, John Doe urges us to _____.

The author’s point is that _____.

The essence of this argument is that _____.

A Concluding Sentence and/or Transition

At the end of particularly long paragraphs, you may include a sentence that summarizes the main idea of that paragraph and gives it closure. The concluding sentence can also serve as a transition to the next paragraph preparing the reader for what’s to come. To learn more about effective transitions, see the Transitions section of this chapter.

Sample Body Paragraphs

The following examples illustrate the basic structure of a body paragraph with its four main elements: a topic sentence, supporting evidence, an explanation of that evidence, a concluding sentence and/or transition.

Sample Body Paragraph

A strong body paragraph should support the claim you make in your thesis statement. Our sample body paragraph develops a key supporting idea from the following argumentative thesis:

Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls—because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times, but spending that much time online is detrimental to their social skills and mental health.

The discussion points that the writer of this thesis statement will have to support in the body of the essay are

- spending too much time online is detrimental to social skills

- spending too much time online is detrimental to mental health

The following sample body paragraph begins to develop the second of these discussion points:

In addition to impeding social development, excessive cellphone use can contribute to a range of mental health disorders. For example, Jean M. Twinge et al., a team of psychology researchers from San Diego State and Florida State Universities, conclude that increased screen time in adolescents is associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms when compared to those engaged in nonscreen activities (9). Moreover, in the same study, the authors report that “adolescents using devices 5 or more hours a day (vs. 1 hour) were 66% more likely to have at least one suicide-related outcome” (9). Teenagers and young adults are not only more likely to engage in problematic use or overuse of cellphones, but because they are still maturing cognitively, they are especially vulnerable to the psychological repercussions.

Color Coding Key:

Topic sentence (bold )

Supporting evidence (red)

Explaining the evidence (blue)

Paragraph and Sentence-level transitions (Italics)

To help students understand the concept of effective paragraph development, writing instructors often create tools, such as the M.E.A.L. Plan and P.I.E.

The M.E.A.L. Plan

The M.E.A.L. Plan allows you to identify and implement the essential elements necessary for creating an effective body paragraph, specifically a body paragraph that incorporates evidence.

M – Main idea (topic sentence) (bold): an arguable claim that tells the point of the paragraph and relates to or expands upon the thesis.

E – Evidence/examples (red): in the form of examples, reasons, illustrations, observations that support the thesis

A – Analysis (blue): explaining the evidence; drawing compelling conclusions; interpreting significance and relevance of ideas

L – Link (transition to thesis and/or next paragraph) (Italics): demonstrating how this point supports your thesis

Example of the M.E.A.L Plan Paragraph

For the following example, the student developed this thesis: Watching violence on television makes children more prone to violence themselves.

Here is the body paragraph with each element of the M.E.A.L. Plan identified:

Children are exposed to many violent acts that make them numb to real-life violence.According to the American Psychological Association, by the time a child reaches the age of eleven, they have seen over 8,000 murders (“Violence in the Media”). This repetitive exposure to violent crimes desensitizes young viewers to violence. They may even find it acceptable to commit violent acts and might see violence as an acceptable way to solve problems just as they have seen done on television.

We see that all the essential elements are present here.

Paragraphs may also combine multiple examples of evidence and analysis, making for arguments that are more complex and persuasive.

Example of the M.E.A.L. Plan Paragraph

Student Nina Sarappo argued that “the federal government should continue to fund the National Endowment for the Arts.” One of her body paragraphs offered the following reasoning in support of this claim, combining multiple main assertions with evidence/examples and analysis to form a complex argument in support of the National Endowment for the Arts:

The National Endowment for the Arts provides grants to schools where art funding is scarce. Since 2008, 80% of school districts have cut art funding and that number continues to rise, especially in low income areas (Boyd). The arts are a vital part of children’s education. Participating in art improves motor skills, decision making and inventiveness (Lynch). According to Locker, learning a musical instrument at a young age can “aid in literacy, which can translate into improved academic results for kids.” It could be argued that if a student wants an instrument or paint then he or she has to work for it. What is lacking in that argument is that “‘musical sensibilities’ develop from ages 0-9” (Cutietta). Children this young cannot work and art isn’t a priority for families whose every dollar goes to putting food on the table. However, compared to middle class children, children in low-income families don’t have the same access to art materials, such as paint, canvas, or a musical instrument because art isn’t a priority for families whose every dollar goes to putting food on the table. While tax dollars go to schools so that they can provide learning materials collectively for children that a single family wouldn’t, classes not required are often cut in low budget education systems. The National Endowment for the Arts can step in, however, giving children access to art materials and musical instruments that can help them improve their lives.

Color Coding Key:

Topic sentence (bold )

Supporting evidence (red)

Explaining the evidence (blue)

Paragraph and Sentence-level transitions (Italics)

The P.I.E. Method

The P.I.E. method works as a global and local framework, meaning you can use this tool to organize the entire essay and individual paragraphs.

Point = the main idea [thesis statement (global), and topic sentence (local)]

Illustration = compelling evidence that supports your point [body paragraphs (global), and direct textual evidence via research and/or quotations from the primary text (local)]

Explanation = a discussion of your direct textual evidence in the context of your argument

If you examine the paragraphs above in the M.E.A.L. Plan section, you’ll find that the P.I.E. elements also exist with the Point being similar to the Main Idea; the Illustration is the same as Evidence; and the Explanation works as both Analysis and Link.

All these methods are valid and can help you organize your ideas in any essay format. Notice that in these methods, the illustration/evidence is a very small part of the whole. Don’t let evidence overwhelm your paragraphs. Your paragraphs should consist mostly of your voice, your ideas, backed up with evidence from sources.

Breaking, Combining, or Beginning New Paragraphs

Like sentence length, paragraph length varies. There is no single ideal length for “the perfect paragraph.” There are some general guidelines, however. Some writing handbooks or resources suggest that a paragraph should be at least seven to nine sentences; others suggest that 100 to 200 words is a good target to shoot for. In academic writing, paragraphs tend to be longer, while in less formal or less complex writing, such as in a newspaper, paragraphs tend to be much shorter. One half of a page is usually a good target length for paragraphs at your current level of college writing. If your readers can’t see a paragraph break on the page, they might wonder if the paragraph is ever going to end, or they might lose interest.

The most important thing to keep in mind here is that the amount of space needed to develop one idea will likely be different than the amount of space needed to develop another.

Question: So, when is a paragraph complete?

Answer: When it’s fully developed. The guidelines above for providing good support should help.

Some signals that it’s time to end a paragraph and start a new one include that

- You’re ready to begin developing a new idea

- You want to emphasize a point by setting it apart

- You’re getting ready to continue discussing the same idea but in a different way (e.g. shifting from comparison to contrast, for example)

- You notice that your current paragraph is getting too long (more than half a page or so), and you think your writers will need a visual break

- You notice that some of your paragraphs appear to be short and choppy

- You have multiple paragraphs on the same topic

- You have undeveloped material that needs to be united under a clear topic

For additional ideas on how to develop stronger paragraphs and how to completely and clearly express your ideas, please review the following handout:

Transitions

So you have a main idea, and you have supporting ideas, but how can you be sure that your readers will understand the relationships between them? How are the ideas tied to each other? One way to emphasize these relationships is through the use of clear transitions between ideas. Like every other part of your essay, transitions have a job to do. They form logical connections between the ideas presented in an essay or paragraph, and they give readers clues that reveal how you want them to think about (process, organize, or use) the topics presented.

Why Are Transitions Important?

Transitions signal the order of ideas, highlight relationships, unify concepts, and let readers know what’s coming next or remind them about what’s already been covered. When instructors or peers comment that your writing is choppy, abrupt, or needs to “flow better,” those are some signals that you might need to work on building some better transitions into your writing. If a reader comments that they are not sure how something relates to your thesis or main idea, a transition is probably the right tool for the job.

When Is the Right Time to Build in Transitions?

There’s no right answer to this question. Sometimes transitions occur spontaneously, but just as often (or maybe even more often) good transitions are developed in revision. While drafting, we often write what we think, sometimes without much reflection about how the ideas fit together or relate to one another. If your thought process jumps around a lot (and that’s okay), it’s more likely that you will need to pay careful attention to reorganization and to providing solid transitions as you revise.

Let’s take some time to consider the importance of transitions at the sentence level and transitions between paragraphs.

Sentence-Level Transitions

Transitions between sentences often use “connecting words” to emphasize relationships between one sentence and another. One suggestion is the “something old something new” approach, meaning that the idea behind a transition is to introduce something new while connecting it to something old from an earlier point in the essay or paragraph. Here are some examples of ways that writers use connecting words (highlighted with orange text and italicized) to show connections between ideas in adjacent sentences:

To Show Similarity

When I was growing up, my mother taught me to say “please” and “thank you” as one small way that I could show appreciation and respect for others. In the same way, I have tried to impress the importance of manners on my own children.

Other connecting words that show similarity include also, similarly, and likewise.

To Show Contrast

Some scientists take the existence of black holes for granted; however, in 2014, a physicist at the University of North Carolina claimed to have mathematically proven that they do not exist.

Other connecting words that show contrast include in spite of, on the other hand, in contrast,and yet.

To Exemplify

The cost of college tuition is higher than ever, so students are becoming increasingly motivated to keep costs as low as possible. For example, a rising number of students are signing up to spend their first two years at a less costly community college before transferring to a more expensive four-year school to finish their degrees.

Other connecting words that show example include for instance, specifically, and to illustrate.

To Show Cause and Effect

Where previously painters had to grind and mix their own dry pigments with linseed oil inside their studios, in the 1840s, new innovations in pigments allowed paints to be premixed in tubes. Consequently, this new technology facilitated the practice of painting outdoors and was a crucial tool for impressionist painters, such as Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, and Cassatt.

Other connecting words that show cause and effect include therefore, so, and thus.

To Show Additional Support

When choosing a good trail bike, experts recommend 120–140 millimeters of suspension travel; that’s the amount that the frame or fork is able to flex or compress. Additionally, they recommend a 67–69 degree head-tube angle, as a steeper head-tube angle allows for faster turning and climbing.

Other connecting words that show additional support include also, besides, equally important, and in addition.

Table 6.1 Most Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| Sequence of Addition | Time Order | Comparison and Contrast |

|

And |

At first |

Similarly |

|

Again |

Soon |

Likewise |

|

Also |

Earlier |

By the same token |

|

Too |

Before |

Furthermore |

|

Moreover |

After |

In comparison |

|

Next |

Finally |

Also |

|

Last |

Then |

Additionally |

|

Besides |

Later |

Moreover |

|

Finally |

Next |

Although |

|

Furthermore |

During |

After all |

|

In addition |

Afterward |

As balanced against |

|

One … another |

At length |

But |

|

First… second…third… |

At the same time |

By comparison |

|

Still |

Now |

Compared to |

|

Additionally |

As soon as |

Conversely |

|

Meanwhile |

Despite |

|

|

In the meantime |

Even though |

|

|

Until |

However | |

|

Immediately |

||

|

Eventually |

||

|

Subsequently |

|

Narrowing of Focus |

Conclusions |

Concession |

|

Definitely |

Accordingly |

Admittedly |

|

After all |

As a result |

Although this may be true |

|

In fact |

As I have said |

Certainly |

|

Indeed |

As I have shown |

Despite |

|

In particular |

Consequently |

Granted |

|

Explicitly |

Finally |

However |

|

Specifically |

Hence |

In spite of |

|

That is |

In brief |

It is true that |

|

In other words |

Lastly |

Maybe |

|

Expressly |

On the whole |

Nevertheless |

|

|

Therefore |

Nonetheless |

|

|

Thus |

Regardless |

|

Cause and Effect |

Example |

|

Hence |

For example |

|

Since |

To illustrate |

|

Therefore |

Especially |

|

Still |

For instance |

|

Notwithstanding |

Thus |

A Word of Caution

Single-word or short-phrase transitions can be helpful to signal a shift in ideas within a paragraph, rather than between paragraphs (see the discussion below about transitions between paragraphs). But it’s also important to understand that these types of transitions shouldn’t be frequent within a paragraph. As with anything else that happens in your writing, they should be used when they feel natural and feel like the right choice. Here are some examples to help you see the difference between transitions that feel like they occur naturally and transitions that seem forced and make the paragraph awkward to read:

Example – Too Many Transitions

The Impressionist painters of the late 19th century are well known for their visible brush strokes, for their ability to convey a realistic sense of light, and for their everyday subjects portrayed in outdoor settings. In spite of this fact, many casual admirers of their work are unaware of the scientific innovations that made it possible this movement in art to take place. Then, In 1841, an American painter named John Rand invented the collapsible paint tube. To illustrate the importance of this invention, pigments previously had to be ground and mixed in a fairly complex process that made it difficult for artists to travel with them. For example, the mixtures were commonly stored in pieces of pig bladder to keep the paint from drying out. In addition,when working with their palettes, painters had to puncture the bladder, squeeze out some paint, and then mend the bladder again to keep the rest of the paint mixture from drying out. Thus, Rand’s collapsible tube freed the painters from these cumbersome and messy processes, allowing artists to be more mobile and to paint in the open air.

Example – Subtle Transitions That Aid Reader Understanding

The Impressionist painters of the late 19th century are well known for their visible brush strokes, for their ability to convey a realistic sense of light, for their everyday subjects portrayed in outdoor settings. However, many casual admirers of their work are unaware of the scientific innovations that made it possible for this movement in art to take place. In 1841, an American painter named John Rand invented the collapsible paint tube. Before this invention, pigments had to be ground and mixed in a fairly complex process that made it difficult for artists to travel with them. The mixtures were commonly stored in pieces of pig bladder to keep the paint from drying out. When working with their palettes, painters had to puncture the bladder, squeeze out some paint, and then mend the bladder again to keep the rest of the paint mixture from drying out. Rand’s collapsible tube freed the painters from these cumbersome and messy processes, allowing artists to be more mobile and to paint in the open air.

Transitions between Paragraphs and Sections

It’s important to consider how to emphasize the relationships not just between sentences but also between paragraphs in your essay.

Transitions take readers by the hand and lead them from one part of your argument to the next. Transitions between paragraphs “glue” paragraphs together and help readers stay focused on the main thesis of your paper. Good transitions can connect paragraphs and turn disconnected writing into a unified whole. Instead of treating paragraphs as separate ideas, transitions can help readers understand how paragraphs work together, reference one another, and build to a larger point.

Here are a few strategies to help you show your readers how the main ideas of your paragraphs relate to each other and also to your thesis.

Use Signposts

Signposts are words or phrases that indicate where you are in the process of organizing an idea; for example, signposts might indicate that you are introducing a new concept, that you are summarizing an idea, or that you are concluding your thoughts. Some of the most common signposts include words and phrases like first, then, next, finally, in sum, and in conclusion. Be careful not to overuse these types of transitions in your writing. Your readers will quickly find them tiring or too obvious. Instead, think of more creative ways to let your readers know where they are situated within the ideas presented in your essay. You might say, “The first problem with this practice is…” Or you might say, “The next thing to consider is…” Or you might say, “Some final thoughts about this topic are….”

Use Forward-Looking Sentences at the End of Paragraphs

Sometimes, as you conclude a paragraph, you might want to give your readers a hint about what’s coming next. For example, imagine that you’re writing an essay about the benefits of trees to the environment, and you’ve just wrapped up a paragraph about how trees absorb pollutants and provide oxygen. You might conclude with a forward-looking sentence like this: “Trees benefits to local air quality are important, but surely they have more to offer our communities than clean air.” This might conclude a paragraph (or series of paragraphs) and then prepare your readers for additional paragraphs to come that cover the topics of trees’ shade value and ability to slow water evaporation on hot summer days. This transitional strategy can be tricky to employ smoothly. Make sure that the conclusion of your paragraph doesn’t sound like you’re leaving your readers hanging with the introduction of a completely new or unrelated topic.

The best paragraph transition begins the following paragraph where the previous one left off. In the following example from a student essay about obesity, the last sentence of one paragraph is this:

Policy makers in America must hold the food industry accountable by creating stringent guidelines that create boundaries on the marketing of the food being advertised—not only to children, but to all Americans suffering from this disease; these policies may be what help in lowering the dangerous percentages of obesity threatening the lives of millions.

The next paragraph follows logically, giving more specifics about how obesity “threatens the lives of millions.”

Obesity is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers.

Moreover, the repetition of the word “obesity” also serves as a transition.

Use Backward-Looking Sentences at the Beginning of Paragraphs

Rather than concluding a paragraph by looking forward, you might instead begin a paragraph by looking back. Continuing with the example above of an essay about the value of trees, let’s think about how we might begin a new paragraph or section by first taking a moment to look back. Maybe you just concluded a paragraph on the topic of trees’ ability to decrease soil erosion and you’re getting ready to talk about how they provide habitats for urban wildlife. Beginning the opening of a new paragraph or section of the essay with a backward-looking transition might look something like this: “While their benefits to soil and water conservation are great, the value that trees provide to our urban wildlife also cannot be overlooked.”

To use transitional topic sentences, you must know the main idea in each paragraph. Often these main ideas appear in the thesis statement – see the following example.

Example – Transitional Topic Sentences

Thesis: The problem of obesity in the United States is amplified by (1) the convenience and low cost of fast-food restaurants, (2) lack of physical activity, and, surprisingly, (3) social class.

The topic sentence of the first paragraph for the above thesis simply introduces the main idea:

First and foremost, consuming (1) fast food on a regular basis may lead to obesity.

In the second topic sentence, however, the first idea is mentioned before the next idea is introduced:

In addition to the prevalence of (1) fast food, (2) lack of physical activity also contributes to the rising obesity rates.

In the third topic sentence, the same process is repeated with ideas (2) and (3).

Not only (2) the lack of physical activity contributes to growing number of obese individuals, but one’s (3) social class does as well.

Here is another example:

Thesis: The young generation’s addiction to their electronic devices leads to (1) dangerous driving habits, (2) poor academic performance, and (3) the increased levels of stress.

The topic sentence of the first paragraph for the above thesis simply introduces the main idea:

Constant use of electronic devices creates (1) distracted drivers and contributes to the texting while driving problem.

In the second topic sentence, however, the first idea is mentioned before the next idea is introduced:

The overuse of electronic devices not only leads to (1) dangerous driving habits, but also contributes to (2) poor academic performance.

In the third topic sentence, the first and second ideas are mentioned before the last idea is introduced:

In addition to (1) poor driving habits and (2) bad grades, the use of electronic devices often leads to the (3) increased levels of stress.

Note: Instead of writing transitions that could connect any paragraph to any other paragraph, write a transition that could only connect one specific paragraph to another specific paragraph.

Evaluate Transitions for Predictability or Conspicuousness

Finally, the most important thing about transitions is that you don’t want them to become repetitive or too obvious. Reading your draft aloud is a great revision strategy for so many reasons, and revising your essay for transitions is no exception to this rule. If you read your essay aloud, you’re likely to hear the areas that sound choppy or abrupt. This can help you make note of areas where transitions need to be added. Repetition is another problem that can be easier to spot if you read your essay aloud. If you notice yourself using the same transitions over and over again, take time to find some alternatives. And if the transitions frequently stand out as you read aloud, you may want to see if you can find some subtler strategies.

Transitions glue our ideas and our essays together. For additional ideas on how to employ transitions effectively, use the following handout.

The Conclusion

The essay conclusion is often the neglected part of the essay, but a strong conclusion finishes an essay, making the ideas more palatable and signaling the end in the way dessert connotes the end of a good meal. Consider your conclusion the bookend to your introduction.

The essay conclusion is often the neglected part of the essay, but a strong conclusion finishes an essay, making the ideas more palatable and signaling the end in the way dessert connotes the end of a good meal. Consider your conclusion the bookend to your introduction.

A good conclusion will include the rephrased thesis statement and briefly highlight the main points of the essay, but it is just the start. In addition, the writer needs to use another writing strategy to give the reader something interesting and memorable in the conclusion, not a rehash of previously discussed ideas.

Conclusion Techniques

Below are several conclusion techniques that good writers can employ when finishing their essay.

- Reverse funnel/pyramid

- Rhetorical questions

- Prediction

- Call to action

- Proposal

- Anecdote

- Quotation

- Combining of strategies

- Connection between introduction and conclusion

Reverse funnel/pyramid

This conclusion technique involves moving from specific to general, from narrow to broad. The writer gradually expands the topic to include more aspects or to be applicable to more situations or people. For example, if an essay focused on karma, the writer might review how karma has impacted him; how it could influence others in their relationships, health, and happiness; and finally, how everyone should pay attention to karma. If an essay had been advocating the health benefits of a vegetarian diet or lifestyle, the reverse funnel conclusion might emphasize that in addition to health, a vegetarian diet can be inviting for people interested in animal and environmental issues. By mentioning the latter two aspects, the writer is inviting readers to follow up on further advantages with vegetarianism and is giving the reader something else to consider. The writer might finish the conclusion with some kind of statement that a vegetarian lifestyle is something that anyone, at any age can partake in to reap multiple health benefits. Again, this broadens the applicability of vegetarianism from one group of people to many.

Rhetorical questions

Asking questions that do not invite debate is another way to close an essay. The writer must be sure that the questions do not really solicit the audience’s opinion; in other words, the audience must agree with the rhetorical questions. An example of a rhetorical question would be if an instructor asked her students if they wanted to pass their English class. Most students would agree that of course, they wanted to pass; otherwise, they would not have paid tuition and book money and spent a semester completing homework. If someone were writing an essay advocating for a college to provide an “early alert system” where college staff notifies students who are failing and tries to provide needed resources to support student success, the author might finish by asking, “What student who really wanted to pass would not want to be made aware of his or her dipping grades? Who would want to spend another semester taking the same course over and paying another semester of tuition dollars if it could have been avoided?” The answer is nobody, so the audience would agree with the writer, which helps cinch the writer’s opinion that providing an early alert system would be beneficial to students.

Prediction of the future

Another effective technique to conclude with is a prediction about what could happen if the author’s opinion is not followed—or the opposite, a prediction about the positive aspects if his opinion is followed. For example, if a paper was about the environment and the writer acknowledged the incredible refugee crisis that has occurred because of political and economic instability, she might predict that unless more is done to rectify the environment, the humanitarian crisis of environmental refugees will dwarf the current political refugee situation.

Proposal

Almost any essay that deals with a problematic topic could be concluded with a call to action. The writer may encourage individuals to take specific small actions to at least partially alleviate the problem or offer a more complex solution that would involve certain companies and organizations. If insufficient research exists on the topic, the writer may call for future study and explain what else needs to be known, investigated, or resolved before a proposal can be offered.

Anecdote/Story

Concluding with a short story or incident can provide a more personal ending to an essay. Basically, the writer is finishing with a short narrative, which likely would include the setting of a scene and dialogue. If the writer began the essay with an anecdote, it is often effective to finish the story or reflect upon the earlier incident. That is not essential, though. One can finish an essay with an anecdote even if the essay did not begin with a story.

Quotation

Including a quote in the conclusion can provide closure to a topic. Generally, the quote should be from a source who is an expert on the topic or has relevant knowledge or experience. Again, like in the introduction, when quoting, the writer needs to cite the source and include an in-text citation of where the quote was published unless it is a common phrase. Generally, the quote should not be the last sentence of the conclusion. The essay writer should reflect on the quote and the last word should be by him, not the quoted source. After all, the essay is the writer’s opinion, so the essay should finish with his ideas.

Combination of strategies

Combining multiple techniques makes for a strong conclusion. A quote might be paired with a prediction or a call to action. A reverse funnel conclusion might lead to rhetorical questions followed by a prediction. Ultimately, the conclusion is a way to complete the whole essay.

Connection between Introduction and Conclusion

A writer may wonder if the same techniques should be used for both the introduction and conclusion. For example, if the essay’s introduction uses the funnel technique, should the conclusion be a reverse funnel? If the introduction employs questions, does the conclusion need to end with rhetorical questions, etc.? The answer is no. The writer does not need to use similar introductory and conclusion techniques, although that is perfectly acceptable. For example, if an essay begins with a story, the writer may decide in the conclusion to finish or add to the story. Or a writer might conclude an essay by quoting from the same source cited in the introduction.

One of the best ways for a writer to finish his essay is to actually refer to the introduction in the conclusion in some way. A writer should think of the introduction and conclusion as bookends to the essay. In the conclusion, the writer refers to a point, question, idea, or even repeats a few words for emphasis from the introduction. The conclusion in some way echoes or reestablishes the connection to the beginning of the essay; it provides the other half of the bookend to the essay. Or, as was stated in the beginning, the conclusion is that tasty bit of chocolate or fruit—a dessert not too rich or heavy, but just right, finishing the essay.

For additional ideas on how to write effective conclusions and examples of the conclusion strategies one should avoid, please review the following handout:

The Title

Many writers don’t create a title till after most of their work is complete. At that stage, they know exactly what they are going to say and how they are going to deliver their message to their audience.

A good title performs two functions: (1) it engages the reader and (2) informs them about the topic of the essay.

Be accurate and specific in your title. The title should let the reader see the link between what it promises and what the essay delivers. Good titles capture the reader’s attention and help them decide if they want to read the essay.

Novice writers often give their essays a “topic title” that names the topic area but does not forecast the problem being addressed. Titles like “Hip-Hop,” “TV Shows,” or “Women in Advertising” are ineffective because they are too vague and do not provide the reader with enough information. Instead of titling your essay “Good Teachers,” why not “How Good Teachers Treat Their Students,” or better yet, use a subtitle: “Good Teachers: Respect Begetting Respect.”

You might include a key word from the focus of your discussion, but your title should not be a sentence. Be consistent with the tone; a serious essay is undermined by a flippant title. In short, use your imagination and be creative; strive to get the attention of your audience.

Several strategies may help the writer achieve these goals.

Question

The writer may state or imply the question the essay addresses.

Examples of Question Titles

Is Hyper-Masculinity a Problem in Today’s Sports?

Does Watching Violence on TV Promote Violent Behavior?

Are Ice Spice and Cardi B Misogynists?

Thesis

The writer may state or imply, often in abbreviated form, the essay’s thesis.

Examples of Thesis Title

Fit, Sexy, and Emotionally Damaged Women of Reality TV

Lessons of Violence, Competition, and Vulgarity in Video Games

Overworked and Underappreciated Heathcare Workers

Two-Part Title

It is not easy to create a phrase that is both engaging and informative. In that situation, the writer may create a two-part title separated by a colon. One part serves to arouse the reader’s interest and may present key words from the essay’s issue or problem or an intriguing “mystery phrase.” The other part informs the reader about the main position of the essay by posing a question, thesis, or summary of purpose.

Examples of Two-Part Title

The Bro Code: Television’s Inaccurate Portrayal of Men

Feed Your Face: Why Your Complexion Needs Vitamins

“Country Girl, Shake it for Me”: Country Music Party Anthems and the Women in Them

To Bee or Not to Bee: Saving Arizona Bees from Extinction

The Perfect Princess: The Influence of Disney Films on Young Girls

Masculinity in Hip Hop: What It Means to Be the Top Dog

Monster in a Can: Problems with Energy Drinks

Please note that academic titles are typically longer and more detailed than the titles in popular media.

To sum it up:

Your essay’s title SHOULD:

- Be original

- Reflect your topic

- Be lively and attention-getting

Your essay’s title SHOULD NOT:

- Be generic/repeat the assignment

- Be in ALL CAPS

- Be in boldface, “quotation marks,” underlined, or italicized

- Be followed by a period

- Always capitalize the first letter of the first word and the last word.

- Capitalize the first letter of each “important” word in between the first and last words.

- Do not capitalize articles (a, an, the), unless they are after a colon

- Do not capitalize coordinating conjunctions (and, but, or, etc.)

- Do not capitalize prepositions (on, at, in, off, etc.)

Key Takeaways

- The introduction to your essay should begin with an attention-grabbing hook and establish background information on the topic, ending with the thesis statement for the paper.

- A body paragraph contains four main elements: a topic sentence, supporting evidence, explanation of that evidence, and a concluding sentence and/or transitions.

- Transitions help ideas move from one to the next smoothly.

- A good conclusion will include the rephrased thesis statement and briefly highlight the main points of the essay, ending with a memorable statement or question.

- A title should engage the reader and inform them of the topic.

Attributions

“The Writing Process” by Kathy Boylan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Body Paragraphs: An Overview” by Amanda Lloyd is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Transitions: Developing Relationships between Ideas” by Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Nicole Rosevear, and Jaime Wood is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Creating a Title” by Sandi Van Lieu is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Rough Drafts” by Excelsior OWL is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image Credits

“Technology Blueprint of a House” by Michael Hiraeth from Pixabay

“Photo of People Doing Handshakes” by Fauxels on Pexels

“Brown Tree” by Neil Thomas on Unsplash

“Brown Metal Train Rail” by Lance Grandahl on Unsplash

“Photo of End Signage” by Ana Arantes on Pexels