A branch of the Nez Percé tribe, from the Pacific Northwest, refused to be moved to a reservation and attempted to flee to Canada but were pursued by the U.S. Cavalry, attacked, and forced to return. The following is a transcript of Chief Joseph’s surrender, as recorded by Lieutenant Wood, Twenty-first Infantry, acting aide-de-camp and acting adjutant-general to General Oliver O. Howard, in 1877.

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

In 1879, Chief Joseph was invited to Washington D.C. He made the following report.

I am glad I came [to Washington D.C.]. I have shaken hands with a good many friends, but there are some things I want to know which no one seems able to explain. I cannot understand how the Government sends a man out to fight us, as it did General Miles, and then breaks his word. Such a government has something wrong about it. I cannot understand why so many chiefs are allowed to talk so many different ways, and promise so many different things. I have seen the Great Father Chief [President Hayes]; the Next Great Chief [Secretary of the Interior]; the Commissioner Chief [Commissioner of Indian Affairs]; the Law Chief [General Butler]; and many other law chiefs [Congressmen] and they all say they are my friends, and that I shall have justice, but while all their mouths talk right I do not understand why nothing is done for my people. I have heard talk and talk but nothing is done. Good words do not last long unless they amount to something. Words do not pay for my dead people. They do not pay for my country now overrun by white men. They do not protect my father’s grave. They do not pay for my horses and cattle. Good words do not give me back my children. Good words will not make good the promise of your war chief, General Miles. Good words will not give my people a home where they can live in peace and take care of themselves. I am tired of talk that comes to nothing. It makes my heart sick when I remember all the good words and all the broken promises. There has been too much talking by men who had no right to talk. Too many misinterpretations have been made; too many misunderstandings have come up between the white men and the Indians. If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them the same laws. Give them all an even chance to live and grow. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief. They are all brothers. The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect all rivers to run backward as that any man who was born a free man should be contented penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases. If you tie a horse to a stake, do you expect he will grow fat? If you pen an Indian up on a small spot of earth and compel him to stay there, he will not be contented nor will he grow and prosper. I have asked some of the Great White Chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me.

…

When I think of our condition, my heart is heavy. I see men of my own race treated as outlaws and driven from country to country, or shot down like animals.

I know that my race must change. We cannot hold our own with the white men as we are. We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. We ask to be recognized as men. We ask that the same law shall work alike on all men. If an Indian breaks the law, punish him by the law. If a white man breaks the law, punish him also.

Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to talk, think and act for myself — and I will obey every law or submit to the penalty.

Whenever the white man treats the Indian as they treat each other then we shall have no more wars. We shall be all alike — brothers of one father and mother, with one sky above us and one country around us and one government for all. Then the Great Spirit Chief who rules above will smile upon this land and send rain to wash out the bloody spots made by brothers’ hands upon the face of the earth. For this time the Indian race is waiting and praying. I hope no more groans of wounded men and women will ever go to the ear of the Great Spirit Chief above, and that all people may be one people.

In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat has spoken for his people.

Sources: Report of the Secretary Of War, Being Part Of The Message And Documents Communicated To The Two Houses Of Congress, Beginning Of The Second Session Of The Forty-Fifth Congress. Volume I (Washington: Government Printing Office 1877), 630; Joseph, “An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs,” The North American Review.

Civil Disobedience

by Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Born in 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau graduated Harvard and taught elementary school. He became friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson, who encouraged his literary talents. Thoreau shared Emerson’s belief in Transcendentalism, a 19th century movement based on the belief that personal reflection and not organized religion was essential to spiritual fulfillment.

On July 4, 1845, Thoreau declared independence from society and moved into a small cabin in wooded property owned by Emerson. He lived on what he grew or found in the woods. He refused to pay taxes because of his opposition to slavery and the US war with Mexico. Convicted of failing to pay taxes, Thoreau spent a night in jail before a relative paid his debt. He wrote the essay “On Resistance to Civil Government” to justify his refusal to pay taxes, and it came to be known as “On Civil Disobedience.”

Thoreau ended his life as a hermit after two years and returned to society, where he continued to write. He became a land surveyor and died the year after the Civil War began.

On Civil Disobedience (1849)

Thoreau’s essay reflects two important themes in American political theory. The first is the skepticism about whether unconstrained majority rule should be the basis of government. Like Tocqueville, Thoreau claimed that majority rule is essentially the triumph of force over right, as the justification for majority rule is essentially that the majority is stronger than a minority. The second theme is the belief that individuals who cannot change government policy through the political process are justified in peacefully violating laws that they believe unjust, as long as they willingly accept the punishment for such violations. Thoreau’s philosophy of non-violent civil disobedience inspired many future Americans, most notably Martin Luther King, Jr.

I heartily accept the motto “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more readily and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe, “That government is best which governs not at all”; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient. The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty, and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm of the standing government. The government itself, which is only the mode which the people have chosen to execute their will, is equally liable to be abused and perverted before the people can act through it. Witness the present Mexican War, the work of comparatively a few individuals using the standing government as their tool; for, in the outset, the people would not have consented to this measure.

This American government—what is it but a tradition, though a recent one, endeavoring to transmit itself unimpaired to posterity, but each instant losing some of its integrity? It has not the vitality and force of a single living man; for a single man can bend it to his will. It is a sort of wooden gun to the people themselves; and, if ever they should use it in earnest as a real one against each other, it will surely split. But it is not the less necessary for this; for the people must have some complicated machinery or other, and hear its din, to satisfy that idea of government which they have. Governments show thus how successfully men can be imposed on, even impose on themselves, for their own advantage. It is excellent, we must all allow, yet this government never of itself furthered any enterprise, but by the alacrity with which it got out of its way. It does not keep the country free. It does not settle the West. It does not educate. The character inherent in the American people has done all that has been accomplished; and it would have done somewhat more, if the government had not sometimes got in its way. For government is an expedient by which men would fain succeed in letting one another alone; and, as has been said, when it is most expedient, the governed are most let alone by it. Trade and commerce, if they were not made of India rubber, would never manage to bounce over the obstacles which legislators are continually putting in their way; and, if one were to judge these men wholly by the effects of their actions, and not partly by their intentions, they would deserve to be classed and punished with those mischievous persons who put obstructions on the railroads.

But, to speak practically and as a citizen, unlike those who call themselves no-government men, I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government. Let every man make known what kind of government would command his respect, and that will be one step toward obtaining it.

After all, the practical reason why, when the power is once in the hands of the people, a majority are permitted, and for a long period continue, to rule, is not because they are most likely to be in the right, nor because this seems fairest to the minority, but because they are physically the strongest. But a government in which the majority rule in all cases cannot be based on justice, even as far as men understand it. Can there not be a government in which majorities do not virtually decide right and wrong, but conscience?—in which majorities decide only those questions to which the rule of expediency is applicable? Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience, then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume, is to do at any time what I think right. It is truly enough said, that a corporation has no conscience; but a corporation of conscientious men is a corporation with a conscience. Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice. A common and natural result of an undue respect for law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder-monkeys and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to the wars, against their wills, aye, against their common sense and consciences, which makes it very steep marching indeed, and produces a palpitation of the heart. They have no doubt that it is a damnable business in which they are concerned; they are all peaceably inclined. Now, what are they? Men at all? or small moveable forts and magazines, at the service of some unscrupulous man in power?…

The mass of men serve the State thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies. They are the standing army, and the militia, jailers, constables, posse comitatus, etc. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw, or a lump of dirt. They have the same sort of worth only as horses and dogs. Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others, as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and officeholders, serve the State chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the devil, without intending it, as God. A very few, as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men, serve the State with their consciences also, and so necessarily resist it for the most part; and they are commonly treated by it as enemies….

How does it become a man to behave toward this American government to-day? I answer that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.

All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to and to resist the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable. But almost all say that such is not the case now. But such was the case, they think, in the Revolution of ’75. If one were to tell me that this was a bad government because it taxed certain foreign commodities brought to its ports, it is most probable that I should not make an ado about it, for I can do without them: all machines have their friction; and possibly this does enough good to counterbalance the evil. At any rate, it is a great evil to make a stir about it. But when the friction comes to have its machine, and oppression and robbery are organized, I say, let us not have such a machine any longer. In other words, when a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army, and subjected to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is the fact, that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets, and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing; who even postpone the question of freedom to the question of free-trade, and quietly read the prices-current along with the latest advices from Mexico, after dinner, and, it may be, fall asleep over them both. What is the price-current of an honest man and patriot today? They hesitate, and they regret, and sometimes they petition; but they do nothing in earnest and with effect. They will wait, well disposed, for others to remedy the evil, that they may no longer have it to regret. At most, they give only a cheap vote, and a feeble countenance and Godspeed, to the right, as it goes by them. There are nine hundred and ninety-nine patrons of virtue to one virtuous man; but it is easier to deal with the real possessor of a thing than with the temporary guardian of it.

All voting is a sort of gaming, like chequers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it. The character of the voters is not staked. I cast my vote, perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, not wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men. When the majority shall at length vote for the abolition of slavery, it will be because they are indifferent to slavery, or because there is but little slavery left to be abolished by their vote. They will then be the only slaves. Only his vote can hasten the abolition of slavery who asserts his own freedom by his vote….

It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong; he may still properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support…. The broadest and most prevalent error requires the most disinterested virtue to sustain it. The slight reproach to which the virtue of patriotism is commonly liable, the noble are most likely to incur. Those who, while they disapprove of the character and measures of a government, yield to it their allegiance and support, are undoubtedly its most conscientious supporters, and so frequently the most serious obstacles to reform. Some are petitioning the State to dissolve the Union, to disregard the requisitions of the President. Why do they not dissolve it themselves—the union between themselves and the State—and refuse to pay their quota into its treasury? Do not they stand in the same relation to the State, that the State does to the Union? And have not the same reasons prevented the State from resisting the Union, which have prevented them from resisting the State?…

Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them? Why does it always crucify Christ, and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?…

Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn. As for adopting the ways which the State has provided for remedying the evil, I know not of such ways. They take too much time, and a man’s life will be gone. I have other affairs to attend to. I came into this world, not chiefly to make this a good place to live in, but to live in it, be it good or bad. A man has not everything to do, but something; and because he cannot do everything, it is not necessary that he should do something wrong. It is not my business to be petitioning the governor or the legislature any more than it is theirs to petition me; and, if they should not hear my petition, what should I do then? But in this case the State has provided no way: its very Constitution is the evil….

I meet this American government, or its representative the State government, directly, and face to face, once a year, no more, in the person of its tax-gatherer; this is the only mode in which a man situated as I am necessarily meets it; and it then says distinctly, Recognize me; and the simplest, the most effectual, and, in the present posture of affairs, the indispensablest mode of treating with it on this head, of expressing your little satisfaction with and love for it, is to deny it then. My civil neighbor, the tax-gatherer, is the very man I have to deal with—for it is, after all, with men and not with parchment that I quarrel—and he has voluntarily chosen to be an agent of the government. How shall he ever know well what he is and does as an officer of the government, or as a man, until he is obliged to consider whether he shall treat me, his neighbor, for whom he has respect, as a neighbor and well-disposed man, or as a maniac and disturber of the peace, and see if he can get over this obstruction to his neighborliness without a ruder and more impetuous thought or speech corresponding with his action? I know this well, that if one thousand, if one hundred, if ten men whom I could name—if ten honest men only—aye, if one honest man, in this State of Massachusetts, ceasing to hold slaves, were actually to withdraw from this copartnership, and be locked up in the county jail therefor, it would be the abolition of slavery in America. For it matters not how small the beginning may seem to be: what is once well done is done for ever….

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison. The proper place to-day, the only place which Massachusetts has provided for her freer and less desponding spirits, is in her prisons, to be put out and locked out of the State by her own act, as they have already put themselves out by their principles. It is there that the fugitive slave, and the Mexican prisoner on parole, and the Indian come to plead the wrongs of his race, should find them; on that separate, but more free and honorable ground, where the State places those who are not with her, against her—the only house in a slave-state in which a free man can abide with honor. If any think that their influence would be lost there, and their voices no longer afflict the ear of the State, that they would not be as an enemy within its walls, they do not know by how much truth is stronger than error, nor how much more eloquently and effectively he can combat injustice who has experienced a little in his own person. Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax-bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution if any such is possible. If the tax-gatherer, or any other public officer, asks me, as one has done, “But what shall I do?” my answer is, “If you really wish to do anything, resign your office.” When the subject has refused allegiance, and the officer has resigned his office, then the revolution is accomplished….

When I converse with the freest of my neighbors, I perceive that, whatever they may say about the magnitude and seriousness of the question, and their regard for the public tranquillity, the long and the short of the matter is, that they cannot spare the protection of the existing government, and they dread the consequences of disobedience to it to their property and families. For my own part, I should not like to think that I ever rely on the protection of the State. But, if I deny the authority of the State when it presents its tax-bill, it will soon take and waste all my property, and so harass me and my children without end. This is hard. This makes it impossible for a man to live honestly and at the same time comfortably in outward respects….

I have paid no poll-tax for six years. I was put into jail once on this account, for one night; and, as I stood considering the walls of solid stone, two or three feet thick, the door of wood and iron, a foot thick, and the iron grating which strain the light, I could not help being struck with the foolishness of that institution which treated me as if I were mere flesh and blood and bones, to be locked up. I wondered that it should have concluded at length that this was the best use it could put me and had never thought to avail itself of my services in some way. I saw that, if there was a wall of stone between me and my townsmen, there was a still more difficult one to climb or break through, before they could get to be as free as I was. I did not for a moment feel confined, and the walls seemed a great waste of stone and mortar. I felt as if I alone of all my townsmen had paid my tax. They plainly did not know how to treat me, but behaved like persons who are underbred. In every threat and in every compliment there was a blunder; for they thought that my chief desire was to stand the other side of that stone wall. I could not but smile to see how industriously they locked the door on my meditations, which followed them out again without let or hinderance, and they were really all that was dangerous. As they could not reach me, they had resolved to punish my body; just as boys, if they cannot come at some person against whom they have a spite, will abuse his dog. I saw that the State was half-witted, that it was timid as a lone woman with her silver spoons, and that it did not know its friends from its foes, and I lost all my remaining respect for it, and pitied it.

Thus the State never intentionally confronts a man’s sense, intellectual or moral but only his body, his senses. It is not armed with superior wit or honesty, but with superior physical strength…

The authority of government, even such as I am willing to submit to—for I will cheerfully obey those who know and can do better than I, and in many things even those who neither know or can do so well—is still an impure one: to be strictly just, it must have the sanction and consent of the governed. It can have no pure right over my person and property but what I concede to it. The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual. Is a democracy such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State, until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at last which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose, if a few were to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men. A State which bore this kind of fruit, and suffered it to drop off as fast as it ripened, would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen.

Concerning the Way in Which Princes Should Keep Faith – The Prince, Chapter 18

by Niccolò Machiavelli

#analysis #proposalargument #systemanalysis #argument #logos #ethos #kairos #politics #sharedvalues

Every one admits how praiseworthy it is in a prince to keep faith, and to live with integrity and not with craft. Nevertheless, our experience has been that those princes who have done great things have held good faith of little account, and have known how to circumvent the intellect of men by craft, and in the end have overcome those who have relied on their word. You must know there are two ways of contesting, the one by the law, the other by force; the first method is proper to men, the second to beasts; but because the first is frequently not sufficient, it is necessary to have recourse to the second. Therefore it is necessary for a prince to understand how to avail himself of the beast and the man. This has been figuratively taught to princes by ancient writers, who describe how Achilles and many other princes of old were given to the Centaur Chiron to nurse, who brought them up in his discipline; which means solely that, as they had for a teacher one who was half beast and half man, so it is necessary for a prince to know how to make use of both natures, and that one without the other is not durable. A prince, therefore, being compelled knowingly to adopt the beast, ought to choose the fox and the lion; because the lion cannot defend himself against snares and the fox cannot defend himself against wolves. Therefore, it is necessary to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves. Those who rely simply on the lion do not understand what they are about. Therefore a wise lord cannot, nor ought he to, keep faith when such observance may be turned against him, and when the reasons that caused him to pledge it exist no longer. If men were entirely good this precept would not hold, but because they are bad, and will not keep faith with you, you too are not bound to observe it with them. Nor will there ever be wanting to a prince legitimate reasons to excuse this non-observance. Of this endless modern examples could be given, showing how many treaties and engagements have been made void and of no effect through the faithlessness of princes; and he who has known best how to employ the fox has succeeded best.

But it is necessary to know well how to disguise this characteristic, and to be a great pretender and dissembler; and men are so simple, and so subject to present necessities, that he who seeks to deceive will always find someone who will allow himself to be deceived. One recent example I cannot pass over in silence. Alexander the Sixth did nothing else but deceive men, nor ever thought of doing otherwise, and he always found victims; for there never was a man who had greater power in asserting, or who with greater oaths would affirm a thing, yet would observe it less; nevertheless his deceits always succeeded according to his wishes,because he well understood this side of mankind.

Therefore it is unnecessary for a prince to have all the good qualities I have enumerated, but it is very necessary to appear to have them. And I shall dare to say this also, that to have them and always to observe them is injurious, and that to appear to have them is useful; to appear merciful, faithful, humane, religious, upright, and to be so, but with a mind so framed that should you require not to be so, you may be able and know how to change to the opposite.

And you have to understand this, that a prince, especially a new one, cannot observe all those things for which men are esteemed, being often forced, in order to maintain the state, to act contrary to fidelity, friendship, humanity, and religion. Therefore it is necessary for him to have a mind ready to turn itself accordingly as the winds and variations of fortune force it, yet, as I have said above, not to diverge from the good if he can avoid doing so, but, if compelled, then to know how to set about it.

For this reason a prince ought to take care that he never lets anything slip from his lips that is not replete with the above-named five qualities, that he may appear to him who sees and hears him altogether merciful, faithful, humane, upright, and religious. There is nothing more necessary to appear to have than this last quality, inasmuch as men judge generally more by the eye than by the hand, because it belongs to everybody to see you, to few to come in touch with you. Every one sees what you appear to be, few really know what you are, and those few dare not oppose themselves to the opinion of the many, who have the majesty of the state to defend them; and in the actions of all men, and especially of princes, which it is not prudent to challenge, one judges by the result.

For that reason, let a prince have the credit of conquering and holding his state, the means will always be considered honest, and he will be praised by everybody; because the vulgar are always taken by what a thing seems to be and by what comes of it; and in the world there are only the vulgar, for the few find a place there only when the many have no ground to rest on.

One prince of the present time, whom it is not well to name, never preaches anything else but peace and good faith, and to both he is most hostile, and either, if he had kept it, would have deprived him of reputation and kingdom many a time.

____________________

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469-1527) was an Italian diplomat, politician, historian, philosopher, writer, playwright and poet of the Renaissance period. He wrote his best-known work The Prince (Il Principe) in 1513.

This work (The Prince, by Niccolò Machiavelli), identified by Project Gutenberg, is free of known copyright restrictions.

The Defense Department Is Worried about Climate Change – and Also a Huge Carbon Emitter

by Neta C. Crawford

Scientists and security analysts have warned for more than a decade that global warming is a potential national security concern.

They project that the consequences of global warming – rising seas, powerful storms, famine and diminished access to fresh water – may make regions of the world politically unstable and prompt mass migration and refugee crises.

Some worry that wars may follow.

Yet with few exceptions, the U.S. military’s significant contribution to climate change has received little attention. Although the Defense Department has significantly reduced its fossil fuel consumption since the early 2000s, it remains the world’s single largest consumer of oil – and as a result, one of the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters.

A broad carbon footprint

I have studied war and peace for four decades. But I only focused on the scale of U.S. military greenhouse gas emissions when I began co-teaching a course on climate change and focused on the Pentagon’s response to global warming. Yet, the Department of Defense is the U.S. government’s largest fossil fuel consumer, accounting for between 77% and 80% of all federal government energy consumption since 2001.

In a newly released study published by Brown University’s Costs of War Project, I calculated U.S. military greenhouse gas emissions in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent from 1975 through 2017.

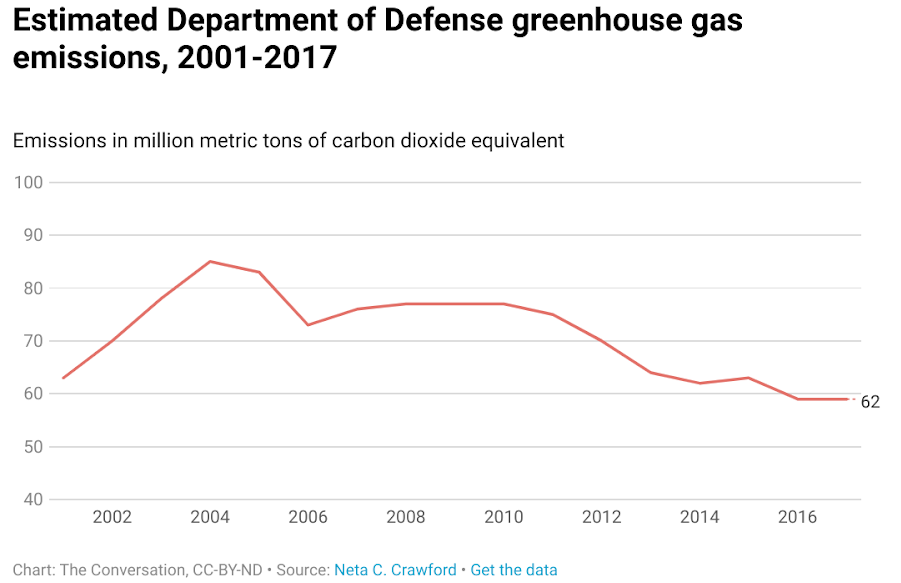

Today China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, followed by the United States. In 2017 the Pentagon’s greenhouse gas emissions totaled over 59 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. If it were a country, it would have been the world’s 55th largest greenhouse gas emitter, with emissions larger than Portugal, Sweden or Denmark.

The largest sources of military greenhouse gas emissions are buildings and fuel. The Defense Department maintains over 560,000 buildings at approximately 500 domestic and overseas military installations, which account for about 40% of its greenhouse gas emissions.

The rest comes from operations. In fiscal year 2016, for instance, the Defense Department consumed about 86 million barrels of fuel for operational purposes.

Why do the armed forces use so much fuel?

Military weapons and equipment use so much fuel that the relevant measure for defense planners is frequently gallons per mile.

Aircraft are particularly thirsty. For example, the B-2 stealth bomber, which holds more than 25,600 gallons of jet fuel, burns 4.28 gallons per mile and emits more than 250 metric tons of greenhouse gas over a 6,000 nautical mile range. The KC-135R aerial refueling tanker consumes about 4.9 gallons per mile.

A single mission consumes enormous quantities of fuel. In January 2017, two B-2B bombers and 15 aerial refueling tankers traveled more than 12,000 miles from Whiteman Air Force Base to bomb ISIS targets in Libya, killing about 80 suspected ISIS militants. Not counting the tankers’ emissions, the B-2s emitted about 1,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases.

Quantifying military emissions

Calculating the Defense Department’s greenhouse gas emissions isn’t easy. The Defense Logistics Agency tracks fuel purchases, but the Pentagon does not consistently report DOD fossil fuel consumption to Congress in its annual budget requests.

The Department of Energy publishes data on DOD energy production and fuel consumption, including for vehicles and equipment. Using fuel consumption data, I estimate that from 2001 through 2017, the DOD, including all service branches, emitted 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases. That is the rough equivalent of driving of 255 million passenger vehicles over a year.

Of that total, I estimated that war-related emissions between 2001 and 2017, including “overseas contingency operations” in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Syria, generated over 400 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent — roughly equivalent to the greenhouse emissions of almost 85 million cars in one year.

Real and present dangers?

The Pentagon’s core mission is to prepare for potential attacks by human adversaries. Analysts argue about the likelihood of war and the level of military preparation necessary to prevent it, but in my view, none of the United States’ adversaries – Russia, Iran, China and North Korea – are certain to attack the United States.

Nor is a large standing military the only way to reduce the threats these adversaries pose. Arms control and diplomacy can often de-escalate tensions and reduce threats. Economic sanctions can diminish the capacity of states and nonstate actors to threaten the security interests of the U.S. and its allies.

In contrast, climate change is not a potential risk. It has begun, with real consequences to the United States. Failing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will make the nightmare scenarios strategists warn against – perhaps even “climate wars” – more likely.

A case for decarbonizing the military

Over the past last decade the Defense Department has reduced its fossil fuel consumption through actions that include using renewable energy, weatherizing buildings and reducing aircraft idling time on runways.

The DOD’s total annual emissions declined from a peak of 85 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2004 to 59 million metric tons in 2017. The goal, as then-General James Mattis put it, is to be “unleashed from the tether of fuel” by decreasing military dependence on oil and oil convoys that are vulnerable to attack in war zones.

Since 1979, the United States has placed a high priority on protecting access to the Persian Gulf. About one-fourth of military operational fuel use is for the U.S. Central Command, which covers the Persian Gulf region.

As national security scholars have argued, with dramatic growth in renewable energy and diminishing U.S. dependence on foreign oil, it is possible for Congress and the president to rethink our nation’s military missions and reduce the amount of energy the armed forces use to protect access to Middle East oil.

I agree with the military and national security experts who contend that climate change should be front and center in U.S. national security debates. Cutting Pentagon greenhouse gas emissions will help save lives in the United States, and could diminish the risk of climate conflict.

____________________

Neta C. Crawford is a professor of Political Science at Boston University and the author of Accountability for Killing: Moral Responsibility for Collateral Damage in America’s Post-9/11 Wars (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, Humanitarian Intervention (Cambridge University Press, 2002.)

The Defense Department Is Worried about Climate Change – and Also a Huge Carbon Emitter by Neta C. Crawford is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Habits and Virtues: Does It Matter if a Leader Kicks a Dog?

by Joanne B. Ciulla

#scholarly #politics #cognitivebias #analysis #argument #research #sharedvalues #definition #ethos #heroes #currentevents

Abstract

This paper argues that it is reasonable to make attributions about a leader’s character based on minor incidents such as kicking a dog. It begins with a short review of the relevant literature from leadership studies and social psychology on how our prototypes of leaders affect the attributions we make about them. Then the paper examines the role of virtues, habits, and dispositional statements to show why an act such as kicking a dog can offer insight into a leader’s moral character.

KEYWORDS: Leadership; Leadership Ethics; Virtue; Habit Attribution; Dispositional Statements

Introduction

Followers watch their leaders. They consciously or unconsciously notice how leaders act in formal, informal, public and private settings and they use this information to draw inferences about leaders’ virtues, vices, habits, and future behavior. One reason they do this is because this personal know- ledge helps compensate for the real or per- ceived power imbalance between leaders and followers.1

There are times when people observe what a leader does in the blink of an eye that influence their opinion of a leader almost as much or even more than his or her entire résumé. This leads one to wonder: Is one instance or one small gesture a fair and reasonable way to make a moral assessment of a leader? We might ask this question about the behavior of anyone but it takes on a special significance in the case of leaders because of the ways they are scrutinized and perceived by followers.

Forum

In this paper, I look at why a seemingly minor act of a leader can influence our perceptions of her moral character, even in the face of other positive information about the leader. For example, would you hire a successful, well- qualified person to be a CEO or vote for a politician who you discovered kicked a dog? What would you think of a leader who kicked a dog? Is dog kicking even relevant to leadership?

For a dog lover it would matter even if he only kicked a dog once; for others it would not matter if he kicked a dog once but it would if he did it all the time. There are also those who would consider dog kicking completely irrele- vant to a leader’s moral character and ability to lead. One simple reason for condemning the behavior is that most people think leaders should be role models but does being a role model require moral perfection in every aspect of life or does it only require that that a leader serve as a model in areas relevant to his or her role as a leader?2

This hypothetical may seem like a trivial thought experiment, yet the point of the question and this paper is to tease out some philosophic insights into an important practical question. What does a small gesture or off- handed behavior tell us about the moral character of a leader?

This question lies at the heart of judgments we make when hiring people for leadership roles and deciding which candidate to vote for in an election. It touches on the relationship between a leader’s public and private morality, her everyday behavior, and behavior that is part of her job. I refer to these minor gestures that people sense are morally signifi- cant as “morality in the miniature”. Morality in the miniature consists of the little things people do that we perceive as indicators of the virtues that they actually possess.3

This paper begins with a short review of the relevant literature from leadership studies and social psychology on how we make attributions about a person’s character and how those attributions are related to our prototypes of what a leader should be like. I will then discuss the role of virtues and habits in ethics as a means of showing why judgments about a leader’s character that are based on incidents of morality in the miniature such as kicking a dog, while subject to error, can offer insights into a leader’s moral character.

Leadership ethics in Leadership Studies

Most of the literature in leadership studies looks at leadership along two main axes. The first axis includes things like behaviors, traits and styles, and the second consists of the historical, organizational, and cultural context of the leader. Studies of leadership usually aim at understanding good leadership, which I have ar- gued means leadership that is both effective and ethical.4

Hence, on the one hand, if one regards ethics and effectiveness as two very separate criteria, the question of dog kicking is irrelevant if the kicker possesses the traits, knowledge, and skills to be an effective leader. On the other hand if one sees ethics as intertwined with leader effectiveness, then dog kicking may be significant. Researchers have yet to discover a universal set of traits that leaders make leaders effective in all contexts,5 nonetheless, most leadership theories have normative aspects to them.6

For instance, some leaders have traits that are effective in a business context but not in a political one. Leadership scholars and practi- tioners have long enjoyed clustering traits and behaviors into ideal types of leadership, most of which make normative assumptions about leaders. A disproportionate amount of the leadership literature consists of research on transformational leadership,7 transforming leadership,8 servant leadership,9 authentic leadership,10 and a construct with a somewhat misleading name called “ethical leadership”.11

The attraction of enumerating the traits or behaviors of leaders under the umbrella of a theory is that you can measure them. Hence the most discussed theories are the ones that have questionnaires, such as transformational, authentic, and ethical leadership. All three of these theories have implicit or explicit normative assumptions. Transformational leadership assumes that the leader inspires followers.12 In James MacGregor Burn’s theory of transforming leadership leaders and followers engage each other a dialogue about values and through this process leaders and followers become morally better. Bernard M. Bass begs the question of ethics by asserting that only ethical leaders are real transformational leaders, whereas he calls the unethical leaders pseudo-transformational.13

From a philosophic perspective the “ethical leadership” construct developed by Michael E. Brown, Linda K. Treviño, and David A. Harrison tests a somewhat peculiar grab bag of things. Some of the questions are about managerial behaviors, such as the leader «listens to what employees have to say», while others are personal moral assessments such as «conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner», and others look like virtues such as «makes fair and balanced decisions».14

Respondents of survey studies such as this one have their own take on the ethical ideas in them but do not usually have the latitude to express their own implicit theory of ethics. Another limitation of these survey studies is they often filter out attributions that are uniquely part of how people construct their idea of a leader.

Agency and implicit theories of leadership

We interpret the behavior of people around us daily. In doing so we also make inferences about their intentions, motivations, traits, and values. People exercise agency when they intentionally do something. Albert Bandura says:

An intention is a representation of a future course of action to be performed. It is not simply an expectation or prediction of future actions but a proactive commitment to bring them about.15

We contrast agency with accidental acts such as tripping over a stone and knocking

someone over. In such cases there is no intent and from a moral point of view, we usually do not assign blame in the same way. The woman did not intend to knock the man over, so we would consider her blameless or perhaps negligent for not watching where she was going. Yet, between accidental behavior and intentional behavior is a third domain and this is what we sometimes call “absent minded behavior”. The leader kicks the dog out of the way and carries on with his business, apparently without thinking about it. This is the domain of morality in the miniature what I want to explore in this paper. Acts that the agent hardly appears to think about that may have moral import.16

It includes cases where a leader does not intentionally do something bad but the fact that he does it has significance to the followers, not because he had bad intentions but because he did it without thinking. Moral agency has an inhibitive form that consists of the power to refrain from acting inhumanely and a proactive form that we express in humane behavior.17 The leader who kicks a dog may raise concerns about his ability to control himself.

Leadership scholars and social psychologists have done extensive research on im- plicit theories of leadership and the role of attribution in leadership. Attributions are ways of inferring the reasons and causes of actions. According to social identity theory, people base their attributions of leaders on their personal prototype of what a leader ought to be like.18 Meindl et al. argue that the attributions concerning leaders are so strong that they call them “the romance of leadership” because people tend to assume that leaders have more power and control over things than they actually do.19

According to Meindl et al. the romance and mystery of leadership may be what sustains followers and moves them to work with leaders toward a common goal but it also creates prototypes of leaders that are unrealistic. If this is true, then all kinds of seemingly trivial behavior may have relevance concerning the behavior of leaders that they may not have for others.

The romance of leadership research illustrates an ethically distinctive aspect of being a leader. Unlike people who are not in leadership roles, we hold leaders responsible for things that they did not know about, did not do, and are unable to control. This is not because people really believe that leaders have agency over everything that goes on. Yet we still give leaders credit for all of the good things that happen under their watch and blame them for the bad, regardless of whether they had anything to do with it. Moral concepts such as responsibility are embedded in many or perhaps most prototypes of leaders. Ideally leaders are the ones who give direction and take responsibility for what happens in a group, organization, or society.

To take responsibility means to accept the role of someone who gets praised, blamed, and has a duty to clean up problems. Taking responsibility is different from being responsible in the sense that an agent may not be personally responsible for doing something or even ordering that something be done. This does not mean that leaders always take responsibility, but this expectation is clear to anyone who has noticed how bad leaders look when they fail to do so. For example, when Americans tried to sign up for health insurance and the government computers crashed, President Obama told the public that he was responsible for the failure. It would have been ridiculous for the President to say, “It’s not my fault. I did not program the computers”.

Attribution errors

As mentioned earlier, we also watch leaders to gain insights into how they will behave in the future. People look for invariances or regularities in human behavior because this helps give order to their world. As Fritz Heider points out, one problem with doing so is that we tend to «overestimate the unity of personality» and look at people in the context of the role that they play.20 Another related problem is one of faulty inductive logic. Sometimes people make the unwarranted generalizations about a person from only one or a few observations. The fact that a man kicked a dog once does not logically warrant the conclusion that he will always kick dogs or always kicks dogs.

When we do not possess knowledge about why the man kicked the dog, we may also discount the behavior because we do not feel we have enough information to make a harsh judgment about the man’s character and in- tent. Hence, we dismiss the act because maybe the man was distracted, under stress, or did not mean to do so. This is called the discounting principle in which the «role of a given cause in producing a given effect is discounted if other possible causes are present».21 While we sometimes make mistakes when we discount bad behavior, we also make mistakes when we fail to consider a person’s background knowledge.

Terry Price argues that leaders make two types of cognitive moral mistakes.22 The first is about the content of morality, meaning that he cannot see why it is wrong to kick a dog. The second kind is about the scope of morality, meaning that he does not place dogs in the category of things that are morally considerable. Understanding that the leader in effect “does not know any better” may be helpful yet it still does not make some behaviors morally excusable.

This leads us to another type of attribution error. Sometimes people do not take into account the context of the behavior and the actor.23 The leader may have kicked the dog because there were rabid dogs in the area. We also have to consider the cultural context of the agent. Sociologists Marcel Mauss and Pierre Bourdieu both use the term habitus to discuss how environment interacts with and shapes behavior. As Mauss notes, people’s habits and the meaning of behavior «vary between societies, educations, proprieties and fashions, and prestige».24 Bourdieu says that individual behavior is a «structural variant of all other group or class habitus».25 Maybe the leader is from a place where dogs are considered ver- min and dog kicking is so normal that no one even notices it.

While people err in failing to take into account the cultural context that affects a per- son’s behavior, they may also make the mistake of assuming that other people react the way that they do or act on the same interests or values that they have.26 This may influence both positive and negative attributions. Hence, the dog lover may think that everyone should have the same respect and concern for dogs that she does. For her, the act of dog kicking as extremely immoral. Whereas a cat lover who hates dogs may approve of the leader’s behavior – if given the chance, she would have kicked the dog too.

Other factors may also influence attributions such as proximity to the event.27 The person who sees the man kick the dog up close may react differently from the person who simply hears about it or watches it on the news. An empathetic witness to the event may feel distress because he hears the dog’s cries and sees its discomfort. This may elicit a feeling of physical disgust, which has been shown to increase the severity of a person’s moral judgment.28 These are just a few factors related to how we misinterpret the behavior of others and make false attributions about their character. Because people tend to carry strong assumptions about what leaders should be like and how they should behave, they tend to be hypersensitive to what leaders do. Now we will examine whether making moral judgments about leaders incidents of morality in the miniature are warranted.

Virtue and virtuosi

The most obvious place to start looking at the moral significance of kicking a dog is in virtue ethics. Aristotle says that moral goodness is the result of habit or hexis. He does not regard hexis as mechanical activity in the way that a behaviorist like B.F. Skinner might think of it.29 Consider the opening of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics:

Excellence of character results from habituation [ethos] – which is in fact the source of the name that it acquired [êthikê], the word for character-trait [êthos] being a slight variation of that for habituation [ethos].30

However, in Aristotle’s and Plato’s ethics, you cannot become virtuous through habit alone. In the Republic, Plato tells us that a person who becomes good «through habit and not by philosophy» is destined to make bad decisions.31 Virtue is not the result of conditioning nor does it include the repetition of a particular behavior – e.g., a courageous person is not always courageous in the same way. It takes knowledge and one might argue, imagination. Thornton C. Lockwood argues that:

Aristotle’s idea of ethical character (ethos) or virtue (aretê) captures the notion of a virtuoso who is responsive in an excellent fashion to what reason perceives in parti- cular and changing circumstances.32

The idea of a virtuous person as a moral virtuoso has some provocative implications for our discussion of morality in the miniature. The definition of the word “virtuoso” consists of the key elements that mirror Aristotle’s idea of virtue. First, it means a learned person who has a special technical skill. Second, is often related to someone with good taste and third, such a person is sometimes a dabbler in a variety of arts.33 A virtuoso has technical skill and knowledge found in (phronesis). The attraction to fine things or taste reminds us of what Aristotle says about being motivated by the love of “the fine”, which are activities that give us pleasure because they are good.34

Aristotle’s ethics assumes that virtues should be practiced regularly. A virtuoso violi- nist should be able to play any piece of music well. If she played a simple piece of music badly, we might wonder if she was really a virtuoso. If a virtuous person is a virtuoso, what do we say about her when she behaves badly in a minor incident?

Aristotle also says that there is a unity of virtues. You cannot practice and have some virtues without having others. Based on Aristotle’s account in the Nicomachean Ethics, such a person should know “the right rule” for practicing a virtue and virtues in a variety of situations.35 For example, courage is facing danger for the right reason. We cannot know what the right reason and hence practice cou- rage without knowing about justice, fairness, and the good life in general.36 Aristotle’s virtue ethics show us why it is reasonable to question the moral character of the leader who kicks a dog. If virtues are supposed to be habits and intertwined with each other, then it makes sense. Here we see a tension between a unified concept of morality and the potential attribu- tion error of overestimating the unity of personality that was mentioned earlier.

Habits

We tend to look assume regularities in human behavior. While this can be problema- tic, it is not always wrong to do so. Habits have always been a difficult part of ethics because they complicate the meaning of an action. Immanuel Kant thought habits undercut the idea of good will, which he saw as the foundation of morality. For Kant, the very idea of ethics rests on following moral laws, especially in cases where we choose respect for the law overcomes our inclinations. Friedrich Nietzsche thought that short-term habits were okay, but disliked “enduring habits” because they prevented humanity from improving itself through “self-overcoming”.37 The negative interpretations of habits are based on their connotation as mechanistic and repetitive behavior. The positive views on habit tend to follow Aristotle’s lead and incorporate free will, reason and intentionality into them.

William James recognized the tension between determinism and voluntary behavior but regarded habit as central to the pragmatist framework. He said that habit serves as “happy harmonizer” of different elements of human experience.38 In a similar light, John Dewey argued that habits are a way for people to link past, present, and future events. He said, «The view that habits are formed by sheer repetition puts the cart before the horse».39 Repetition is the result of a habit, not its cause. Habits are formed by knowledge, socialization, and reason, which we then streamline into behavior. Kicking dogs may be a bad habit, but since habits are not mindless, the agent is still accountable for what happened before he began to repeatedly exercise the behavior.

In some ways, David Hume’s account of habit captures the concern people feel when they witness acts of morality in the miniature. Hume says that moral judgments are about custom or habit and they vary across time and culture. On Hume’s view, it is reasonable to assume that if a person kicks a dog once, he will do it again or perhaps do other similarly bad things. Hume writes:

The supposition, that the future resembles the past, is not founded on arguments of any kind, but is deriv’d entirely from habit, by which we are determined to expect for the future the same train of objects, to which we have become accustom’d.40

While people may read situations incor- rectly when they make snap judgments about a leader based on some small act, Hume tells us they may do so because they have seen causal connections between things like dog kicking and other bad behaviors.40

According to Hume it makes sense to be concerned about a leader who kicks a dog; however, in the same light Hume admits that this opinion can be changed by evidence to the contrary. As Hume famously said:

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.41

When we witness any small unsavory gesture of a leader, it may elicit a feeling of discomfort in part, Hume argues, because it is associated with something else we have seen or some other causal connection between such behaviors in the past. Hume notes that the passion or feeling we might have is not unreasonable unless we discover that it is “accompanied by a false judgment”.42 In that case it is the judgment not the feeling we have about the act that is unreasonable.

Integrity of morality

One bone of contention about virtue ethics is based on the attribution errors of assuming that virtues are unwavering character traits and assuming that behavior depends more on a leader’s character than the context of it.43 Critics argue that people cannot rely on virtues to resist behaving badly when others around them are. Even Machiavelli offers this “nice guys finish last” argument about leaders:

If a ruler who wants always to act honorably is surrounded by many unscrupulous men his downfall is inevitable.44

Robert C. Solomon uses emotions to explain the relationship between virtue as a personal quality and a behavior that is influenced by context. He says emotions are part of virtues and since emotions are reactive to other people and situations, it is foolish to deny that virtues depend on the environment and yet that does not mean they are totally determined by it.45

In contrast to Solomon, Gilbert Harman argues that moral philosophers sometimes commit the fundamental attribution error of assuming that certain behaviors are indicative of moral character traits. He calls this “misguided folk morality” and his argument privi-eges the empirical research of psychologists over the moral theories of philosophers.46

Assuming that human beings are more consistent than they are is a psychological question. Experience and numerous experiments have demonstrated that character is not necessarily a stable part of human behavior. Yet, I do not think that these experiments imply that to avoid attribution errors people should change the moral ideals inherent in their prototypes of leaders. One reason why the philosophers we have discussed are interested in habits is because the idea of consis- tency is fundamental to the idea of what it means to be ethical. Also, consistency is especially important in leadership for building trust giving people a sense of security. So, when we see a man leader kick a dog, it is not unreasonable to wonder if that behavior is consistent with or indicative of other behaviors, just as we wonder about the virtuoso who cannot play a simple piece of music.

People often talk about a leader’s integrity, sometimes as if it is a psychological quality and sometimes as if it is a moral quality. The description of moral integrity has as many definitions as there are writers in the leadership literature. Leadership scholars often define integrity as a cluster of moral concepts that usually include honesty and sometime they use integrity to refer to all aspects of a leader’s ethics. The descriptive meaning of the word “integrity” is wholeness and that wholeness is the umbrella over all aspects of morality or as Aristotle says, “the rule”. When a person has a virtue it is a hexis because we do not expect moral qualities to be selectively exercised or exercised in isolation from other virtues. As David Baum notes, integrity refers to a personal completeness that describes a person’s unbroken or uncorrupted character.47 While integrity is central to how we think of a person’s moral character, it is also central to how we think about their immoral character. So our other intuition about the leader kicking a dog is that the incident may represent a tear in the fabric of the leader’s morality. The alternative to this view of integrity is the assumption that people easily compartmentalize their moral behavior. On this view unsavory behavior in a leader’s private life or outside of the leader’s actual work irrelevant to his or her job as a leader. While this may be true in some cases, we also see cases where followers stop discounting this kind of bad behavior because they have enough evidence to see how a leader’s bad private behavior or dog kicking affects how they lead.

Dispositional properties

We have been discussing how we might make sense of the dog kicking incident form the perspective of leadership studies, psychology, and moral philosophy. Philosophy provides other insights into the problem based on how we formulate our ideas in language. In The Concept of Mind, Gilbert Ryle offers a way to think about attribution based on the statements we make about the “dispositional properties” of people and things. He says dispositional statements:

Apply to, or are satisfied by, the actions, reactions and state of the object; they are inference-tickets, which license us to pre- dict, retrodict, explain and modify these actions reactions and states.48

Following the work of Ludwig Wittgen- stein, Ryle believes that language has an ela- sticity of significance.49 When we make the dispositional statement that someone is a dog kicker, we are not saying that the person is currently kicking a dog, has repeatedly kicked dogs in the past, or will kick dogs in the future; nor are we reporting on observed or unobserved behavior. Dispositional statements do not narrate incidents but «if they are true, they are satisfied by narrated incidents».50

So an observer may see a leader kick a dog and make the statement “the leader is a dog kicker”. This statement is not true or false but rather a provisional statement about the lea- der. The meaning of the statement depends on whether it fits with other narratives of events in which we are able to see a family resemblance to dog kicking. For instance, dog kicking might at some point become meaningful in the narrative of other behaviors such as humiliating low-level subordinates. Ryle’s analysis of statements about dispositional properties gives us a way of understanding how a person might think about the act of dog

kicking. She may infer from the leader kicking the dog a tentative set of dispositional properties ranging from cruelty, to disdain for subordinates, to impatience, etc., and then watch to see if these qualities manifest themselves in his behavior as a leader. This is analogous to Hume’s point about judgments. We may make a wrong judgment based on the facts, but our thinking about how we feel at the time is sound. It is neither illogical nor false to say that someone who kicks a dog once is a dog kicker. Dispositional statements have the po- tential to refer to acts of morality in the miniature that may or may not at some point be either relevant to or even constitutive of a person’s morality as a whole.

No more dogs! A real case

At this point the reader is probably weary of hearing about a leader kicking a dog, so let us look at a real example that illustrates the way people use an observation of morality in the miniature to gain insight into a person’s morality. Several years ago, the manager of a large Wall Street bank told me a story of the time that they tried to hire a “superstar” broker away from a competitor to lead a new division of his company. The management team had met with the broker many times over a period of months to convince him to join their firm. After a number of interviews, long lunches, and conversations with the broker, he agreed to join the bank. On the way out of the office after the final interview, the broker turned to the receptionist and said “honey, get me a taxi and move it, I’m in a hurry”. 51

The receptionist blushed and looked surprised at being addressed in such a rude fashion. The interviewers witnessed his behavior and were quite surprised by it. The man had not behaved that way before and they assumed that he should know better. After the incident, they started to feel uneasy about him. Despite his stellar track record as a broker, his academic credentials, and the fact that they thought he would make a lot of money for the bank, something about him did not seem right. The question on their minds was a question about his virtue: “Is he in the habit of behaving this way?”

They not only wondered about how he treated women and subordinates but they started to wonder how he did other things. Was this a tear in the fabric of his character? The incident compelled them to take a closer look into the broker’s background. After further investigation they discovered that the- re were indeed problems that were unrelated to how he treated women or subordinates, but about how the broker did business. The managers decided not to hire him because they worried that he had “risky habits”.

This case illustrates how morality in the miniature can offer potential clues into a per- son’s character. While being rude to a woman is more serious than being rude to a dog, the behavior indicated an inconsistency from their previous observations about his behavior and fit in their organization. One might object that perhaps lapses like the broker’s are a one- off and it would be unfair to judge him by it.

Yet, the case illustrates is that by viewing actions as morality in the miniature they did not condemn the man based on one act or how they felt about his behavior. Rather, the broker’s behavior led them to question his character. Some organizations take the idea characterized by morality in the miniature seriously. They look for insights into job candidates’ character by taking them out to lunch and observing how they treat the server. The assumption being that if they are rude to the waitress then they might be rude to subordinates.

Conclusion: Why the little things matter

The case about the broker is exemplified by the saying, “where there is smoke, there is fire”. I am not willing to make such a strong claim about the leader who kicks a dog. Instead what I have attempted to show in this paper is that where there is smoke, it makes sense to keep an eye out for fire. Leadership scholars have shown us that people have prototypes of leaders that influence their attributions of them. Psychologists have demonstrated how people make attribution errors about the character of leaders, such as ignoring the context of the behavior or overestimating the unity of personality.

We also know that prototypes of leaders usually entail moral theories or moral norms. As we have seen, the anchor of many moral theories is that a person’s moral character requires some sort of consistency and coherency such as in Aristotle’s idea of a unified and intertwined set of virtues. The fact that people have free will and behave inconsistently does not mean that we should remove the expectation of moral coherence from our assumptions about morality or from the moral ideals inhe- rent in our prototypes of leaders. 52

By viewing a virtue as something that a person practices all the time and is related to other virtues, we set a high standard, especially for leaders who have the power to do great good or harm to others. So while such assumptions about virtue may be wrong from a psychological point of view, they are not necessarily wrong from a philosophical one.

By assuming that the character of a leader is on display in a variety of behaviors from the small gesture to intentional act, we are able to hold leaders to a high standard of morality. We should pay attention to acts of morality in the miniature because such acts serve as red flags that alert us to potential problems. Like the rest of us, leaders are morally imperfect.

Yet unlike the rest of us, the consequences of their moral imperfections can potentially do immediate or long-term harm to many people. This is why leaders should be watched (especially by citizens in a democracy) and why the off-handed things leaders do may matter. I am not arguing that we should obsess over everything that a leader does, but rather that it is reasonable to pay attention to the acts that seem inconsistent with what you know about the leader, or behavior that could be indicative of other problems.

Lastly, we live in an era when we know more about our leaders than ever before. The 24-hour news organizations watch and dissect everything that high-level leaders say and do. Some find it difficult to sort through what is relevant and what is not relevant to a leader’s moral character, especially in politics. When faced with too much information it becomes all too easy to say that the little things do not mat- ter as long as the economy is good or the company makes a profit. Nonetheless, history has shown us that this is always true. While kicking a dog may not bear any relationship to a person’s moral character, in the case of leaders the stakes are sometimes too high to simply ignore it.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my colleague Prof. George R. Goethals for is helpful suggestions concerning the social psychology literature and Prof. Ruth Capriles for her insightful comments.

Notes

1See M.HOGG,D.VAN KNIPPENBERG, Social Identity and Leadership Processes in Groups, in: M.P.ZANNA(ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. XXXV, 2003, pp. 1-52.

2See T.L.PRICE, Why Leaders Need not be Moral Saints, in: J.B.CIULLA(ed.), Ethics, The Heart of Leadership, ABC Clio LLC, Santa Barbara (CA) 2014, III ed., pp. 129-150.

3See J.B.CIULLA, Leadership and Morality in the Miniature, in:A.J.G.SISON (ed.), The Handbook on Virtue Ethics in Business and Management, Springer, New York (forthcoming).

4See J.B.CIULLA, Ethics and Effectiveness: The Na-ture of Good Leadership, in: D.V.DAY,J.AN-TONAKIS(eds.), The Nature of Leadership, Sage, Thousand Oaks (CA) 2011, II ed., pp. 508-540.

5See B.M.BASS, Bass &Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research and Managerial Ap-plications, Free Press, New York 1990, III ed.

6See J.B.CIULLA, Leadership Ethics: Mapping the Territory, in: «TheBusiness Ethics Quarterly», vol. V, n.1, 1995, pp. 5-24.

7See B.M.BASS, Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, Free Press, New York 1985.

8See J.M.BURNS, Leadership, Harper &Row, New York 1978.

9See R.K.GREENLEAF, Servant Leadership:A Journey Into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness, Paulist Press, Ramsey (NJ) 1977.

10See F.LUTHANS,B.J.AVOLIO, Authentic Lea-dership Development, in: K.S.CAMERON,J.E.DUTTON,R.E.QUINN(eds.), Positive Organizati-onal Scholarship,Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco 2003, pp. 241-261.

11See M.E.BROWN,L.K.TREVIÑO,D.A.HARRI-SON, Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Per-spective for Construct Development and Testing, in: «Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes»,vol.XCVII, n. 2, 2005, pp.117-134.

12B.M.BASS, Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, cit.

13B.M.BASS,P.STEIDLMEIER, Ethics, Character, and Authentic Transformational Leadership Beha-vior, in: «Leadership Quarterly»,vol. X, n. 2, 1999, pp. 181-217. And see Terry Price’s critique of it, T.L.PRICE, The Ethics of Authentic Trans-formational Leadership, in: «Leadership Quarterly»,vol. XIV,n. 1, 2003, pp. 67-81.

14M.E.BROWN,L.K.TREVIÑO,D.A.HARRISON, Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing, cit., p. 138.

15A.BANDURA, Social Cognitive Theory: An Agen-tic Perspective, in: «Annual Review Psychology», vol. LII, 2001, pp. 1-26, here p. 6.

16I limit my discussion here to acts that we per-ceive to be bad or immorality in the miniature and save my discussion of such good acts for another paper.

17See A.BANDURA, Moral Disengagement in the Perpetuation of Inhumanities, in: «Personality and Social Psychology Review», vol. III, n. 3, 1999, pp. 193-209.

18See M.HOGG,D.VAN KNIPPENBERG, Social Identity and Leadership Processes in Groups, cit.

19See J.R.MEINDL,S.B.EHRLICH,J.M.DUKERICH, The Romance of Leadership, in: «Administrative Sci-ence Quarterly», vol. XXX, n. 1, 1985, pp. 78-102.

20See F.HEIDER, The Psychology of Interpersonal Re-lations,John Wiley & Sons, New York 1958, p. 55.

21See H.H.KELLEY, Attribution in Social Interac-tion, in: E.E.JONES,D.E.KANOUSE,H.H.KELLY,S.VALINS,B.WEINER, Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior, General Learning Press, Mor-ristown (NJ), 1972, pp. 1-26, here p. 8.

22See T.L.PRICE, Explaining Ethical Failures of Leadership, in: J.B.CIULLA(ed.), Ethics, The Heart of Leadership,Praeger, Westport (CT) 2004, II edition, pp. 129-146.

23See H.H.KELLEY, Attribution in Social Interac-tion, cit., p. 18.

24See M.MAUSS, Techniques of the Body(1935), in: M.MAUSS, Sociology and Psychology. Essays, translated by B.BREWSTER, Routledge and Kegan, London 1979, pp. 95-123, here p. 101.

25P.BOURDIEU, Outline of a Theory of Practice(1972), translated by R.NICE, Cambridge Univer-sity Press, Cambridge, 1977, p. 86.

26See H.H.KELLEY, Attribution in Social Interac-tion, cit.

27See F.HEIDER, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations, cit.

28See S.SCHNALL,J.HAIDT,G.L.CLORE,A.H.JORDAN, Disgust as Embodied Moral Judgment, in: «Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin», vol. XXXIV, n. 8, 2008, pp. 1096-1109.

29See B.F.SKINNER, Beyond Freedom and Dignity,Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1971.