Pop Culture

Are Batman and Superman the Barometer of Our Times? A Review of ‘Superheroes in Crisis’

by Ira Erika Franco

#heroes #review #artsandculture, #analysis, #scholarly, #informative

Abstract

The WWII historian Jeffrey K. Johnson studies how the two comic book legends Superman and Batman have adapted successfully to American cultural and social landscapes through time. This is a book review of ‘Superheroes in Crisis’, a monograph that details some decisive moments from their creation in the late 30’s up to the 70’s in which both characters have transformed in order to maintain their relevance as what Johnson calls ‘cultural barometers’.

Keywords: superheroes , history , batman , superman , monographs

The idea that superhero comic books are part of a modern American mythology is probably not a surprise to anyone. However, Jeffrey Johnson refocuses this concept in his monograph Superheroes in Crisis (RIT Press, 2014): after going into detail of the myriad of changes Superman and Batman have gone to stay relevant, he suggests we should narrow our assumptions of what constitutes a true comic book myth, given that the character stays true to what the present society demands. ‘American culture is littered with faint remembrances of characters who flourished for a season and then became inconsequential and vanished’ (Johnson 2014: 104). The author mentions The Yellow Kid and Captain Marvel as those characters who were once über famous and popular and now are but receding memories in people’s minds. Avid comic readers can surely think of many other examples of great modern characters who, for some reason, just didn’t make it. Batman and Superman, however, remain ‘two heroes who have survived, and often thrived, for over seventy years because they are important to current Americans and speak to modern social problems and contemporary cultural necessities’ (Johnson 2014: 104).

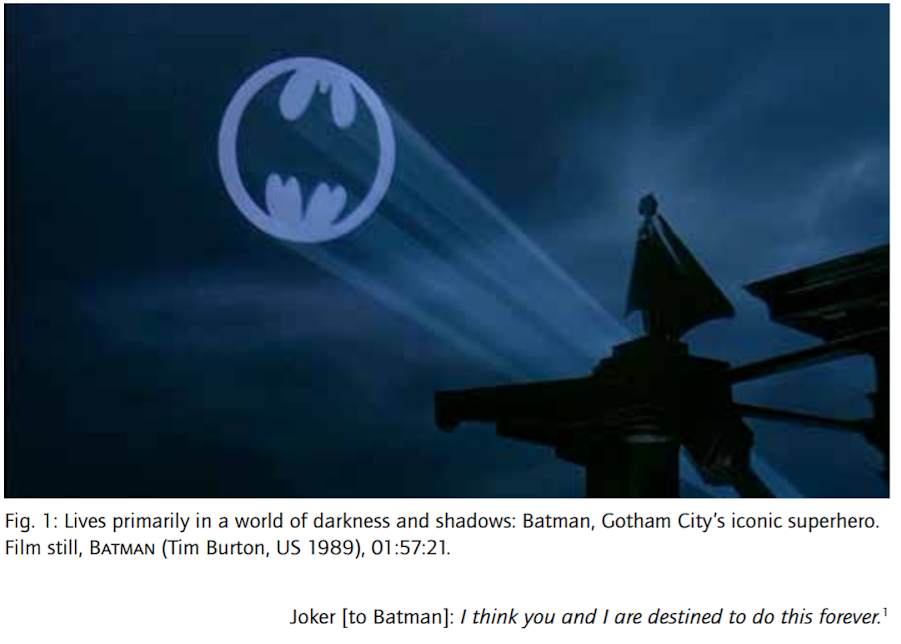

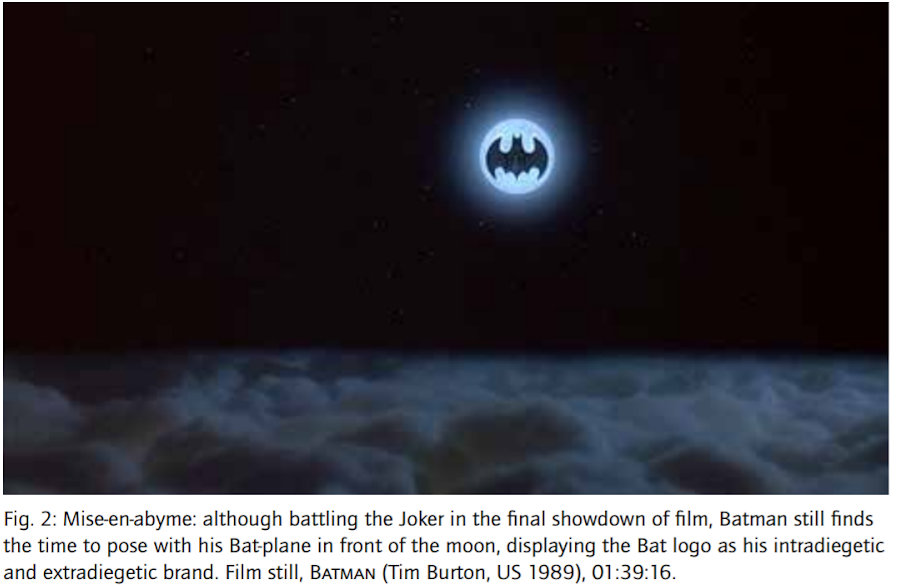

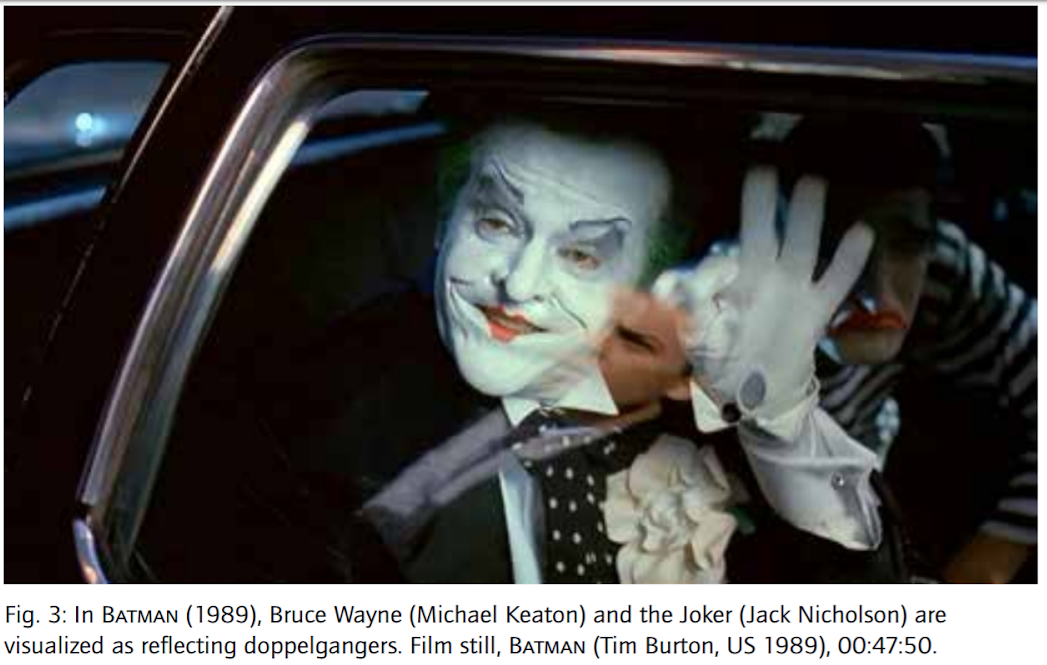

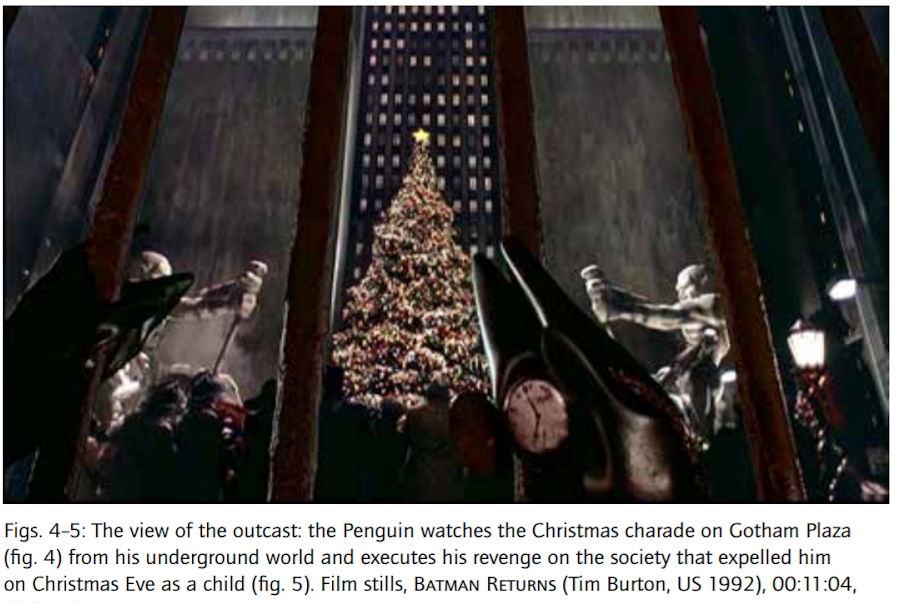

A noted World War II historian, Johnson points out that the characters have endured the trials of time mainly because of their abilities to bend so as not to break. Even if most of us modern readers assume fixed traits for both The Dark Knight and The Man of Steel, Johnson carefully demonstrates there’s no such thing: Superman couldn’t even fly in his earliest adventures, and through the period of the TV series in the mid-sixties, Batman, the so-called Dark Knight, was a goofy, campy character with not a bit of darkness in his soul. Through Johnson’s account it is evident, though, that Batman and his creators have done a better job than Superman’s in adjusting to radical changes in American society (such as the US’s disillusionment after JFK’s assassination or the introduction of TV and its immediate popularity). This might also be the reason for Batman’s smoother translation to modern cinema: since the release of the first movie —Batman (Burton, 1989)— has always kept the public interest with strong sales figures, —The Dark Knight (Nolan, 2008) being the most popular to date, having made 533 million dollars in revenue for its creators in the US alone —. Not even the bad Batman movies have flopped in opening weekends: people always want to see The Dark Knight’s new metamorphosis, as if they wanted to understand what they’ve turned into.

In the four chapters of the book, Johnson provides the reader with the rare pleasure of being told old stories, gems actually: instead of just sociological analysis and high ideas, Johnson provides the actual plot of the comic issue he chooses in order to support his commentary. We might remember that Superman was created during the Great Depression (1938), and it’s fairly easy to assume that the caped hero was to provide a temporary escape for impoverished and desperate Americans, but unless we have an infinite (and expensive) golden age collection, it would probably never occur to us that during his first few years, Superman was actually a savior of the oppressed, almost in a Marxist fashion. One example is Action Comics #3, where Superman disguises himself as a coal miner to trap the mine owner and his socialite friends underground in order to show them the importance of safety regulations and working men. In Action Comics #8, Superman befriends a gang of delinquents and decides to burn down the slums they live in, just to prove that the government is partly responsible for their delinquency. In the end, Superman becomes a true hero: he forces the government to build new apartments providing these hooligans the dignity they deserve. Throughout the book, Johnson provides such examples in effective ways to prove the Historic turmoil to which our heroes reacted.

One compelling topic that defines both characters concerns their enemies. At first, being created as depression-era social avengers, they fight the common criminal: shoplifters, wife-beaters and even politicians. ‘These often colorful foes provided action and adventure while also creating a binary narrative of good and evil’ (Johnson 2014, XIV). But this narrative changes greatly throughout time, constituting probably the most important transformation in the stories of these two heroes: the evolution of their foes. At some point, the duality of pure good and evil stops being good enough. It stops explaining what is wrong with the world. At the end of the sixties, for example, Superman’s petty villains become so unimportant that, for a while, his love interest Lois Lane impersonates a new kind of foe. In a way, Lois updates better than Superman as she wakes up to her newfound power, akin to the zeitgeist of her era. In Lois Lane #85 (she even gets her own title for a little while) the one-time docile girlfriend decides she no longer wants to marry Superman and refuses his once longed-for offer. In a kind of confused, first approach feminism, she is seen doing things such as lifting heavy stuff like men. ‘Superman represents the older generations and is pressing to protect the status quo, while Lois is a change-minded baby boomer’ (Johnson 2014: 43).

Image 1

Superman’s Girlfriend, Lois Lane Vol 1 #80, Curt Swan, Leo Dorfman, DC Comics, January, 1968. Image via Wikia, DC Comics Database, http://dc.wikia.com/wiki/Superman’s_Girlfriend,_Lois_Lane_Vol_1_80. © DC Comics.

Batman’s enemies are, without a doubt, the most exciting ones. First of all, he gets one in the real world: he is accused of promoting homosexuality by the psychologist Frederic Werthan, in his book Seduction of the Innocent (1954), for which Americans changed the regulation code of the comic book industry. Later, in the early sixties, the character is handed to writer and editor Julius Schwartz and the stories become enriched with a focus on Batman’s detective skills. The Riddler, Mr. Freeze and the Joker all demand The Caped Crusader’s brainpower to discover complex noir plots, creating a three-dimensional world within the comic’s pages: ‘Perhaps most interesting is Detective Comics#332 (October 1964) in which Batman fights Joker for the first time under the new creative regime. In this story the Clown Prince of Crime creates a potent dust that causes anyone it comes in contact with to laugh uncontrollably. After encountering the drug, Batman researches possible cures and learns that a simple antihistamine will stop the uncontainable laughter. The Caped Crusader soon thwarts the villain’s evil plans and protects society from the psychopathic clown. This version of Batman is portrayed as being clearly more intelligent and cunning than his arch-nemesis, but The Joker is also more nefarious and crafty than he had been in recent appearances’. (Johnson 2014, 36). It is only natural to think that Batman’s foes evolve in complexity over time, the greatest example being a villain like Ra’s al Ghul, who, defying normal stereotyping, commits awful crimes believing it is best for the planet.

In this constant reshaping of the characters, one thing remains constant from the beginning: the foes are more metaphorical than the heroes for the darkest fears of American society in the way they reflect the heroes’ moral codes. In the first chapter, for example, that covers the early years (from 1938 to 1959), most evildoers evoke the desperate need of common people to keep America’s status quo. Superman fights against gamblers taking control over football games and ‘declares war on reckless drivers’. Superman deals with them using the moral code of an entire society: he enjoys humiliating, beating and sometimes even killing them. ‘These first superheroes were violent champions for a hardened people who demanded they act in such a way. The original versions of Superman and Batman did not conform to the rules against killing, maiming, battling authority figures and law enforcement’ (Johnson 2014: XVII). Johnson thinks these initial times can be seen, especially in Superman, as a kind of an adolescence because of his disregard for any point of view except his own. More a bully than a hero, Superman reflects the state of millions of Americans, adult men out of work ‘who had descended into hopelessness and Superman served as a bright spot in this bleak depressing age’ (Johnson 2014: 2).

Just three years later, with the entry of the US to World War II, the nature of both criminals and heroes changed radically: both Batman and Superman had to support governmental and military mandates, slowly becoming in the years to come guardians of the conventional values that were established with the prosperity and the sense of social unity that came after the victory over the Axis armies. What happened to our heroes in the sixties reflected a harsh division in the American people: while Superman becomes almost infected with paranoia and self-righteousness that characterized the conservatives in the post war era —having nightmares of being exposed to red kryptonite, splitting into evil Superman and good Clark Kent, turning into a space monster, among other adventures—, Batman goes through some nice years of detectivesque narrative, preparing for the blossoming of sexual liberation and anti-war movements that would become popular among youngsters a few years later. ‘The Dark Knight was now focusing more on his detective skills and was no longer fighting aliens or magical beings as he had in previous years…Batman was attempting to recreate himself from an evolving society, but it was unclear if a return to his detective roots combined with pop art influences was what readers demanded’ (Johnson 2014: 35).

One last thing is to note of this book: the detailed attention Johnson pays to the creative minds that shaped these heroes. Bob Kane may have designed Batman to be a ‘hardcore vigilante’, but it was Julius Schwartz in 1964 who invented some of his most engaging traits as a resourceful hard-boiled detective with no other tools to fight crime but his mind. Writers and artists like Frank Robbins, Bob Brown and Dick Giordano are mentioned as inventive, but Johnson points out a very short but fertile period in the seventies that would prepare the dark and gothic traits of Batman we have come to love, under the hands of writer Denny O’Neal and artist Neal Adams. In this period Batman first gets his many layers as a character, his neurosis and most subtle psychological features that Frank Miller would use in his ground-breaking The Dark Knight Returns (1986), later revamped for Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight’s Trilogy.

Above all, the great journey this book offers is discovering how our beloved heroes appear to be two ends of the same rope, because, paradoxically, even when they change, they stay the same: Superman representing (mostly) the moral standards of the conservative side of American society, and Batman exploring (mostly) the darker, subterranean side, both equally sustaining and fundamental to the American social fabric.

References

- Batman (1989). Burton, Tim Warner Bros.

- Johnson, JK (2014). Superheroes in Crisis: Adjusting to Social Change in the 1960s and 1970s. RIT Press. 122

- The Dark Knight (). Trilogy is a film series directed by Christopher Nolan. It consists In: Batman Begins (2005), The Dark Knight (2008) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012). Warner Bros Pictures.

- Werthan, Frederic . (1954). Seduction of the Innocent In: New York Reinhart & Co.. 400

____________________

Ira Erika Franco is is a teacher in Communication for the National Autonomous University of Mexico. She is a film director, a travel writer, and a film and theater critic. Her work appears in Chilango and Muy Interesante. This review is reprinted from The Comics Grid.

Are Batman and Superman the Barometer of Our Times? A Review of ‘Superheroes in Crisis’ by Ira Erika Franco is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License.

The Black Muslim Female Fashion Trailblazers Who Came before Model Halima Aden

by Kayla Renée Wheeler

Media reports have celebrated Halima Aden becoming the first woman to be featured in the Sports Illustrated annual swimsuit edition wearing a hijab or a burkini. In the past, she has appeared on the covers of Allure, British Vogue and Glamour Magazine.

As a scholar who studies black Muslim fashion, I often find that reporters covering Muslim women’s fashion seem to have the notion that Islam and fashion are incompatible.

This attitude ignores the influence black people have had on Muslim fashion going back at least eight decades.

Early Islam in the US

First, it’s important to understand the long history Muslims have in the United States.

According to the Pew Research Center, black Muslims account for one-fifth of all Muslims in the United States. Islam first came to the United States with enslaved Africans.

Their numbers were small, ranging from 30,000 to 40,000. However, as historian Sylviane Diouf notes, enslaved African Muslims left a lasting impact on black American culture, especially in the Sea Islands and Lowcountry region, the coastal area stretching from North Carolina to northern Florida.

The first Islamic text in the United States, the Bilali Document, was written by an enslaved African living on Sapelo Island named Bilali Muhammad in the 19th century. It includes rules about daily prayers and a list of beliefs of Muslims.

Another important text – perhaps the only known narrative by an enslaved person in Arabic – was written by Omar ibn Said in 1831, who lived as a slave in North Carolina. In it, he recounts his life in Senegal, including his religious education. The autobiography also includes several Muslim prayers.

Clothing as identity

In the 20th century, black Americans were reintroduced to Islam through several people and organizations.

These included the Moorish Science Temple of America and the Nation of Islam. The Moorish Science Temple of America was founded by a Moorish American, Noble Drew Ali, in 1913 in Newark, New Jersey.

Drew Ali taught his followers that they were not Negros or Ethiopians, rather they were Moors and that Islam was their true religion. According to Drew Ali, Moors are descendants of the ancient Moabites who founded Mecca, one of the most important cities in Islam.

W.D. Fard Muhammad, who founded what would become known as the Nation of Islam in 1930 in Detroit, Michigan, also taught his followers that they had forgotten their true identity as Asiatic Muslims and members of the lost tribe of Shabazz. The term Asiatic referred to black people and other people of color.

Clothing played a central role in constructing a unique black Muslim identity. Black Muslim women used their dress to challenge American beauty standards, which typically holds thin young white women as the ideal beauty. Their dress practices also challenged beliefs that Islam was only an Arab religion by encouraging members to develop their own local dress practices.

In the Moorish Science Temple of America, male members wore fezzes or turbans and women wore turbans often paired with long shift dresses as part of their everyday wear.

Men in the Nation of Islam dressed in tailored suits and bow ties or ties. Women donned a Muslim Girls Training uniform. The Muslim Girls Training included lessons for women and girls on the rules and beliefs of the Nation of Islam as well as how to cook, clean, raise children and practice self-defense. The uniform included a high-neck tunic that came down to the thigh. It was paired with either loose-fitting pants or a skirt that came to the ankles.

Black Muslims

In my forthcoming book, I argue that Nation of Islam and the Imam W.D. Mohammed community have played an important role in developing the modest fashion industry in the United States. Imam W.D. Mohammed took over the leadership of Nation of Islam in 1975, following the death of his father Elijah Muhammad, who had succeeded the founder W.D. Fard Muhammad.

These organizations and their members have organized fashion shows and operated clothing stores centered on Islamic modesty since the 1960s. The models were usually volunteers from the local community.Elijah Muhammad discouraged female members from embracing the fashion trends of the day.

The fashion shows were a means of highlighting the creative ways Nation of Islam women could dress modestly and maintain the unique aesthetic, while still looking beautiful. They featured diverse head coverings such as berets and fezzes, color-block outfits and different takes on the classic Muslim Girls Training tunic.

Imam W.D. Mohammed and his members would continue to encourage women’s fashion ventures. They incorporated Afrocentric inspired designs and clothing, like the dashiki and kente cloth.

For a decade, starting in the 1960s, when the oldest daughter of Elijah Muhammad, Ethel Muhammad Sharrieff led the Muslim Girl’s Training, clothing became a way of building a self-sustaining black Muslim community.

A clothing factory she managed produced the official Muslim Girl’s Training uniform. Members were encouraged to buy the uniform from the factory. Temple #2 clothing, a store in Chicago, Illinois, sold a wide range of products including shoes, lingerie and jewelry.

Fashion shows

This May, I attended the Sealed Nectar Fashion Show, an annual fashion show hosted by the Atlanta Masjid of al-Islam in Atlanta, Georgia. It is one of the longest-running Muslim fashion shows in the United States, with 2019 marking its 33rd anniversary.

The fashion show was founded in 1986 by Amira Wazeer, an Atlanta-based designer, as a means of celebrating beauty and modesty. This year’s theme, “World Traveler,” featured six black Muslim women designers from the United States, Tanzania and Kenya.

More recent ones include in cities such as Washington D.C., Houston and an upcoming one in Philadelphia.

The fashion shows and bazaars highlight black women’s creativity and diverse definitions of Islamic modesty. This includes different styles of wrapping head scarves – turbans and buns that leave the neck and ears exposed to show off jewelry – as well as multiple clothes layering techniques, like wearing a pair of skinny pants under a short dress.

Black Muslim models

What Aden has been able to accomplish in three years is certainly worth celebrating. She has opened the doors for other hijabi models like Ikram Omar Abdi, who was featured on the cover of Vogue Arabia along with Aden and another Muslim model, Amina Adan.

However, in my view, it is important to place Halima Aden within the larger history of black Muslim fashion in the United States. Unless we do that, there is a risk of erasing the black Muslim fashion trailblazers who came before her and made her rise possible.

____________________

Kayla Renée Wheeler an Assistant Professor of Area & Global Studies and Digital Studies at Grand Valley State University. Her essay first appeared in The Conversation.

The Black Muslim Female Fashion Trailblazers Who Came before Model Halima Aden by Kayla Renée Wheeleris licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

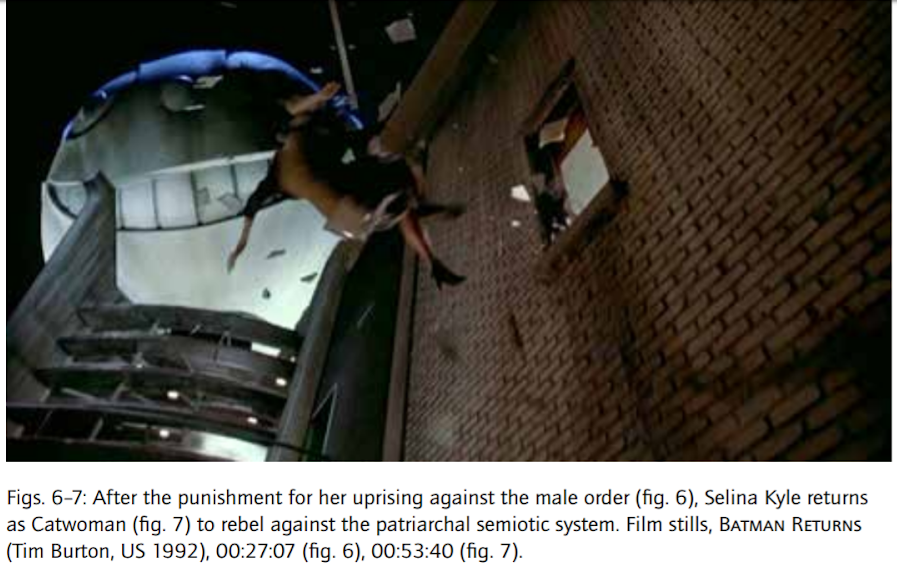

Catwoman’s Hyde: A Comparative Reading of the 2002 Catwoman Relaunch and Stevenson’s Novella

by Lesa Syn

#heroes #review #academic #analysis #artsandculture #descriptive #scholarly

Abstract

This article advocates that the comic character of Catwoman is a comic incarnation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edward Hyde. It does this first by problematizing Andreas Reichstein’s reading of Batman as Hyde (1998). While the similarity between Bruce Wayne and Dr. Henry Jekyll is considerable (such as both being accomplished and affluent men of science who have nocturnal alter egos), Hyde embodies hedonistic desire and loss of control while Batman is the incarnation of discipline and control. This work then goes on to offer the numerous and stark similarities between Hyde and Catwoman, such as offering their counterparts animalistic freedom and the ability to achieve unification through embracing their darker halves. Because of her desire to embrace her dual human experience, the hero/villain Catwoman encapsulates the most human of comic characters.

Keywords: Catwoman , Batman , Hulk , Henry Jekyll , Edward Hyde , Ed Brubaker , Darwin Cooke , Robert Louis Stevenson , Andreas Reichstein , Identity Split , Hero/Villain , animalistic

Who is stronger, Catwoman or Hulk? In stark contrast to the Hulk, who is arguably the strongest comic-book character ever, Catwoman—like her beloved Batman—is one of the few comic-book characters that is “not super-powered, an alien, or a mutant,” but rather entirely human (Orr 1984: 176–177). Well, almost entirely human. Therefore, comparing Catwoman to Hulk may as well be comparing a person to a natural disaster; however, Jason Ranker (2008) discusses a comparison of these dissimilar comic characters… and, believe it or not, the comparison is apt.

In his research, Ranker highlights how Catwoman and Hulk represent stereotypical versions of strength constructed along gender lines; however, there is a better reason to place these two in a category of their own. Unlike almost every other character in the comic book multiverse, these two characters are both heroes and villains, often at the same time. Hulk continues to be one of the greatest threats to Earth but he is also a founding member of The Avengers. Similarly, Catwoman is a villain on par with the rest of Forever Evil, but she is also a founding member of the new Justice League of America (see Figure 1): “Unfortunately, being a fence-sitter on the thin line separating good and evil doesn’t make her a neutral party” (Beatty 2004: 36). These are ambivalent characters that are neither absolute good nor evil, but are constantly torn between both aspects—they are both modern and powerful Edward Hydes.

Perhaps it can be argued that several villains have aspects similar to Robert Louis Stevenson’s iconic Edward Hyde. Two-Face is a literal Janus figure and often physically depicts both good and evil, and Clayface’s inability to fully control his transformation often results in Hyde-like horror in those around him. However, Two-Face does not suffer from his ambivalence, but simply relegates his dual nature to the fate of a coin flip. Clayface is not noble, like Jekyll, but rather is a disguised monster. Catwoman and her alter ego Selina Kyle, torn between both evil and good, are the only true Hyde and Jekyll of Gotham.

Adam Capitainio (2010) has thoroughly compared Marvel’s Bruce Banner and the Incredible Hulk to Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, so this paper will move the discussion to the similar intellectual and emotional torment of DC’s Kyle and Catwoman. To accomplish this task, this paper will first problematize Andreas Reichstein’s (1988) reading of Batman as Mr. Hyde and then it will offer tangible evidence—especially from Brubaker, Cooke, and Allard’s 2002 Catwoman relaunch—that, despite the physical dissimilarities of Kyle to Jekyll, Catwoman is a more complete version of a modern day Mr. Hyde.

Is Batman an American Mr. Hyde?

Reichstein (1998) makes a compelling argument that Batman’s alter ego Bruce Wayne is an American Jekyll. Beyond the obvious comparisons of the successful, popular, and affluent bachelors, these are men of prominence and success who only transform into their alter egos at night. Reichstein highlights that despite both men being childless, Wayne and Jekyll have paternal affection for others: Wayne cares for his various wards and “Jekyll confesses how he had a father’s concern for Hyde” (Reichstein 1998: 340). Reichstein also discusses how both Wayne and Jekyll spend the vast majority of their free time in their secret laboratories, conducting various chemical experiments.

However, the staunchest similarity between these two characters is their double lives. Reichstein explains, “Besides all these formal similarities between Wayne and Jekyll, the essential link between these characters lies in their basic trait: their double identity, their double personality” (Reichstein 1998: 343). As Philip Orr discusses, “[When] Bruce Wayne refers to the Batman, he is not referring to himself in the third person; rather he is referring to the other” (Orr 1995: 174). Rather than just one person with two aspects, Wayne and Batman are two distinct individuals who just happen to exist within a common body. Wayne even confesses this idea to a psychologist: “I guess, we’re all two people—one in daylight and one we keep in shadow” (Batman Returns). Similarly, in his final confession, Dr. Jekyll writes, “With every day, and from both sides of my intelligence, the moral and the intellectual, I thus drew steadily nearer to that truth … that man is not truly one, but truly two” (Stevenson 1886: 77). Clearly, both of these men of science are all too intimately familiar with the dual nature of humanity, and their polarizing personalities. However, it is worth highlighting that the parallels between these two characters lie almost exclusively along the similarities of Wayne and Jekyll.

As such, while Wayne is an American Jekyll, what is the answer to Reichstein’s (1998) titular question “Batman—an American Mr. Hyde?” Both Batman and Hyde are empowered shadows of their other selves, and are able to accomplish what neither Wayne nor Jekyll ever could. They achieve this power by embracing animalistic aspects of their personalities. Jekyll describes his other self as playing “ape-like tricks” (Stevenson 1886: 91) and possessing “ape-like spite” (93). Capitainio explains, “This suggests that Hyde, as the hidden side of Jekyll’s personality, is representative of the animal past and behavior that human beings have necessarily repressed in their quest for ‘civilization’” (Capitainio 2010: 250).

While Jekyll is an accomplished pinnacle of human evolution—generous, brilliant, scientific, attractive, and affluent—Hyde returns this character to his evolutionary ape-like past, which was a common theme in the Gothic novels of the 1890s (Reichstein 1998: 346). Regarding the newfound freedom and anonymity of becoming Hyde, Jekyll writes, “And thus fortified, as I supposed, on every side, I began to profit by the strange immunities of my position” (Stevenson 1886: 86). Batman too is able to tap into his primal animal form—in this case a bat—and uses this animal aspect to achieve his deepest desire for vengeance against the criminal element that orphaned him as a child. Batman also allowed Wayne to safely fulfill his desires for vigilantism.

While such similarities exist between Hyde and Batman, one of the most interesting parallels between these two characters is that both of them murder adversaries in their initial appearances. Mr. Hyde brutally assaults Sir Danvers Carew after a perceived insult: “And next moment, with ape-like fury, he was trampling his victim under foot and hailing down a storm of blows, under which the bones were audibly shattered and the body jumped upon the roadway” (Stevenson 1886: 27). Similarly, in Batman’s first appearance, he is holding the villainous Stryker when “… suddenly, Stryker, with the strength of a madman, tears himself free from the grasp of the Bat-Man…” (Finger and Kane 1939: 6). Stryker then pulls out a gun and shoots at Batman, but Batman punches Stryker, knocking him over the rail and into an acid tank, to which Batman comments, “A fitting end for his kind” (Finger and Kane 1939: 6). While both men have murdered an adversary, Hyde has killed an upstanding gentleman and must pay for his action with his life, while Batman has killed a murderer and deserves an accolade. Hyde must hide behind Jekyll or face the gallows, whereas Batman can continue crime-fighting, and be a vigilante without repercussion. Despite the consequences of these actions, Hyde only longs to kill, while Batman resolves to never take a life.

While surface similarities—such as the stark similarities between their alter egos, empowerment through animalistic disguise, and both having taken a life—exist between Hyde and Batman these characters are as dissimilar from each other as they are from their better halves. For Jekyll, becoming Hyde was embracing and savoring his dark side, “I knew myself, at the first breath of this new life, to be more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to my original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted me like wine” (Stevenson 1886: 79). Jekyll seems to use Hyde to indulge his baser desires. This is completely different from Batman whose “armor/costume harnesses the evil inside and outside of him, as well as protects against repressed sexual desires” (Reichstein 1998: 348). While Hyde is allowed to run rampant, participating in any debauchery that he comes upon, Batman focuses only on punishing criminals.

Most of all, Hyde embodies Jekyll’s willing loss of control, while “Wayne/Batman is control” (Reichstein 1998: 347). After Hyde has killed Carew, Jekyll abandons the potion that unleashed his sinister self, but Hyde continued to reassert himself. Hyde manifests himself at first in dreams and then in reality by forcing the transformation unaided by any chemical concoction. Jekyll could not stop Hyde from taking over their body more and more. Batman, on the other hand, could be taken off at any time, cast aside. Reichstein explains, “He can don the costume/armor whenever he wants and drop it again to become Bruce Wayne” (Reichstein 1998: 348). Reichstein ultimately concludes, “Thus, Batman really is an American cousin of Edward Hyde” (Reichstein 1998: 350). However, this paper suggests that by Reichstein’s definition, Hyde’s familial relationship might as well just as easily include comic book characters such Green Arrow or Iron Man, both of whom are—beneath their masks—affluent playboy bachelor inventors who don costumes/armors to combat evil. While the similarities between Jekyll and Wayne are notable, Batman is not a complete Hyde.

No, but Catwoman Is

However, Catwoman, on the other hand, shares many similarities with Hyde. Jekyll describes the initial transformation into like this: “I felt younger, lighter, happier in body; within I was conscious of a heady recklessness, a current of disordered sensual images running like a millrace in my fancy, a solution of the bonds of obligation, an unknown but not an innocent freedom of the soul” (Stevenson 1886: 78). Kyle too feels the strength and freedom of her alter ego: “That had been one of the reasons for the mask, initially. To help provide. That and the excitement… the adventure. Don’t kid yourself that they weren’t a big part of it, too” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 48). There is a youthful vibrancy and hedonistic abandonment to both Hyde and Catwoman. Catwoman is unbridled. Throughout Catwoman’s history, she is known as thief, and she ultimately ignores societal rules while helping herself to whatever she desires. Ed Brubaker explains, “She was like Robin Hood, except she forgot to the money to the poor” (Beatty 2004: 6). Catwoman, like Hyde, is in it for the freedom and youthful thrill.

Jekyll and Hyde, Kyle and Catwoman are completely different people from their counterpart selves. Hyde has his own apartment and his own companions that exist in totally different circles than Jekyll. Similarly, as Beatty explains, “Aside from a few friends and lovers, Selina and Catwoman are two different women moving in different worlds. And that suits them both just fine” (Beatty 2004: 19). Jekyll/Hyde and Catwoman/Kyle are in actuality two individuals who share one common body and one common memory, but share little else.

Hyde and Catwoman are impervious shields for their more noble halves. No matter the potential atrocities that Hyde could ever commit, Jekyll believes that at any moment he could dispense Hyde instantly and permanently:

Think of it—I did not even exist! Let me escape into my laboratory door, give me but a second or two to mix and swallow the draught that I had always standing ready; and whatever he had done, Edward Hyde would pass away like the stain of breath upon a mirror; and there in his stead, quietly at home, trimming the midnight lamp in his study, a man who could afford to laugh at suspicion, would be Henry Jekyll. (Stevenson 1886: 82).

Through his potion, Jekyll could transform into his shadow self and fulfill his most monstrous desires. In the same vein, in The Dark End of The Street, Kyle embraces her bestial aspect, throwing off all moral, legal, and earthly limitations by transforming herself into a Cat-Woman. In this comic, The Cat-side is able to beat up her (masculine) enemies, climb tall buildings, and seemingly fly through the air (via her whip).

It is important to note in Catwoman history, she was known as “The Cat” and first appeared in the first issue of Batman in 1940. However, in 1950, ten years after “The Cat’s” inception, the mild-mannered alter ego Kyle was named. It is a common misconception that Kyle came first—not a decade later—but this idea of the villainous side appearing before the sociality acceptable persona parallel’s Stevenson’s novella in which the story of Hyde accosting the young girl appears pages before the discussion of Jekyll. This argument will now go back to a previous quote from Jekyll, “I knew myself, at the first breath of this new life, to be more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to my original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted me like wine” (Stevenson 1886: 79). Jekyll seems to use Hyde to indulge his baser desires, but in reality the reverse is true—Hyde uses Jekyll for his own desires.

The problem is that these shielding personas eventually took on a life all their own. Hyde lashed out at his alter ego, punishing him through the destruction of Jekyll’s belongings: “Hence the ape-like tricks that he would play me, scrawling in my own hand blasphemies on the pages of my books, burning the letters and destroying the portrait of my father” (Stevenson 1886: 91). In Brubaker, Cooke, and Allread’s comic, Catwoman too began to have a life outside of Kyle, who says, “The mask is part of who I am now. But it’s also part of the problem, too… because it became a person all on its own” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 54). Thus, while Hyde and Catwoman were created to liberate their alter egos and allowed them to achieve humanly-impossible, animalistic acts, these personas became whole persons in and of themselves. The animal-side uncontrollable and often exhibits behaviors that are outside of normative human roles. Catwoman is wild, something that Kyle struggles to understand (Figure 1). Furthermore, in Figure 1, this Cat-self bides for ownership of the body she cohabitates and eventually becomes intricately integrated and a fully realized being.

Ultimately, Hyde asserts himself and begins replacing Jekyll. The problem is that, with Carew’s murder on his head, Hyde’s only salvation lies in being Jekyll, but he could not condemn himself to perpetual torpor; as such, “Unable to compound the remedy that turns him into Dr. Jekyll again one day, Jekyll/Hyde kills himself” (Reichstein 1998: 339). Similarly, in this comic, Catwoman killed off both Kyle and then herself (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 16)… or at least Catwoman went through a lot of trouble to make it appear that way. Hired to find out if Catwoman truly was dead, Detective Slam Bradley asks the-very-much-alive Kyle, “But a while back, you killed off Selina Kyle… and a few months ago, you killed Catwoman, too… so, the question is—who’s left to find?” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 33). Kyle reemerges and tries to live again, believing that Catwoman is dead and buried; however, Catwoman too refuses to stay dead. As Orr says, “[Catwoman] won’t be killed” (Orr 1994: 181). Catwoman’s immortality is in fact the sole attribute that Ranker’s (2008) work offers as to why she is stronger than the Hulk. Beatty too notes, “Selina definitely has nine lives considering the number of times she has survived near-fatal catastrophes” (Beatty 2004: 25). While most often the nine lives of the Catwoman are seen in response to her battle with others, this immortality applies to her battle with Kyle as well.

The immortal Catwoman torments Kyle, much as Hyde tortures Jekyll: “And this again, that the insurgent horror was knit to him closer than a wife, closer than an eye; lay caged in his flesh, where he heard it mutter and felt it struggle to be born” (Stevenson 1863: 91). Kyle struggles to control the beast within her, but unlike Jekyll who does not seek to understand Hyde—Kyle grapples with accepting Catwoman as a part of herself. Kyle waits a moment and then answers Bradley’s question: “I don’t know. Hopefully someone who can look in the mirror without any pain” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 16). In the mirror here, Kyle sees all the pain that she has caused and that she has endured. Jekyll has a similar mirror experience, but his is all the more tragic because of the loss of control that it represents: “[and] bounding from my bed I rushed to the mirror. At the sight that met my eyes, my blood was changed into something exquisitely thin and icy. Yes, I had gone to bed Henry Jekyll, I had awakened Edward Hyde” (Stevenson 1886: 83).

It is important to highlight that mirrors denote the true representation of self. Christian Metz explains how it is only through a mirror that people can understand themselves and construct their egos: “Thus the child’s ego is formed by identification with its like, and this in two senses simultaneously, metonymically and metaphorically: the other human being who is in the glass, the own reflection which is not the body, which is like it” (Metz 1975: 48–49). Metz underscores the duality of co-existence of each individual’s two selves—the rational ego and the primal id. Thus, by a proverbial mirror, Kyle is able to be a full self, and it is in this mirror, that she understands the Cat’s self. Another way to put it is that the animal-self allows Kyle the only way for her survive and to be a full and actualized person. Whereas the rest of humanity strives to deny the animalistic id inside them, Kyle realizes that she ultimately needs to embrace her Cat self into her life.

Whereas Jekyll embraced the concept of humanity’s dual nature, he theorized that each person was in reality a conglomeration of individuals forced confined in uncomfortable cohabitation: “I hazard the guess that man will be ultimately known for a mere polity of multifarious, incongruous and independent denizens” (Stevenson 1886: 78). In her nightmares, Kyle wrestles, not with Catwoman, but with the vast multitude of individuals that exist inside her: “Like everything I’ve ever been is struggling inside me… trying to find some place to fit themselves” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 44). On the surface, it is easy to focus simply on the duality, but for both Jekyll and Kyle, the double personalities that they battle are just the beginning, as if both these two—and everyone of us for that matter—could just as easily say, “My name is Legion; for we are many” (Mark 5: 9).

While Kyle and Catwoman embody just two persons that inhabit their body, there are multitudes of others. Ignoring the staunch differences in attitude and mannerisms between Kyle and Catwoman, both characters pronouncedly vacillate in skin tone and costume within themselves—even just within this single comic book. For instance, while the panels within the comic showcase a Catwoman who is very overtly a pale Caucasian brunette, the various covers from this same comic depict a darker complected Kyle that is clearly mulatto, Hispanic, or even Italian (see Figure 3, left side). However, even this ethnic alteration pales to the disguises that Kyle dons that make her unrecognizable, the staunchest of which is when Kyle goes undercover as a blond bombshell (see Figure 3, right side). Thus comic’s art work is indicative of Kyle and Catwoman’s personality and multiplicity. Despite all of her various incarnations, Kyle and Catwoman are always at their cores women: “She was a ‘woman,’ and all woman at that” (Madrid 2009: 248). Kyle summons up her female alter egos, uses them as tools, and discards them just as quickly. Kyle can control all these incarnations of herself—other than Catwoman.

Kyle’s therapist asks her, “How long has it been now since you put on the [Catwoman] outfit?” to which Kyle replies, “The outfit? Oh, yeah… that. Almost six months” (Brubaker, Cooke, and Allred 2002: 45). Like Jekyll, Kyle has tried to repress her own Hyde by abandoning the hide of Catwoman. Also like Jekyll, Hyde (i.e.: Catwoman) fought back: “[But] I was still cursed with my duality of purpose; and as the first edge of my penitence wore off, the lower side of me, so long indulged, so recently chained down, began to growl for license” (Stevenson 1886: 87). Catwoman plagues Kyle with

hellish dreams in which she is surrounded by Catwomen who set Kyle on fire, burning away her humanity and leaving only the silhouette of the Catwoman (see Figure 2). In this suffering, Kyle is like Jekyll: “I began to be tortured with throes and longings, as of Hyde struggling after freedom” (Stevenson 1886: 85). Kyle feels the Cat personality struggling for freedom. However, Kyle tries to avoid the temptation of becoming Catwoman—which is why she is seeing a therapist—but Catwoman refuses to let her get a moment’s peace until Kyle acquiesces. Catwoman refuses to let Kyle be complete until Kyle fully embraces all of her aspects.

Conclusion

Reichstein tries to reduce Catwoman to little more than one of the “mostly bizarre array of villains in the Batman comics, like the Joker, the Penguin, the Catwoman … [who] reflect the purely bad side of Batman—like counterparts, or mirrors showing him what would happen to him if he lost control” (Reichstein 1998: 346–347). However, Catwoman should not be reduced to simply reflect the bad side of Batman. While Bruce Wayne is similar to a Dr. Henry Jekyll, Batman is not a complete Mr. Edward Hyde… but Catwoman is.

This argument suggests that Catwoman is such an integral part of Kyle and that her life is shattered—without her “other.” While other critics have studied Batman and Hulk—no one has considered Catwoman as Hyde. It is interesting to note that Kyle logically and consciously puts on Catwoman and both co-habitat the same space. Again, this is very akin to Jekyll and Hyde, who—although different in body and manner—share the same memory (Stevenson 1886: 85) and handwriting (89). These are two parts of a cohesive whole, both vying for control over their life while staunchly rebelling against being controlled by any man (even a Batman) and any law.

Reichstein succeeds at linking Jekyll with Wayne, but she ignores the complexity of comparing Hyde to Batman. Thus, this work corrected that oversight by advocating Jekyll and Hyde story is about identity structure: the socially acceptable personality versus the uncontrollable and often intolerable. A close examination of Dark End of the Street reveals the identity problems in Stevenson’s novella also manifest in Kyle and Catwoman. This comic reinforced the Jekyll side is about social conformity, whereas the Hyde represents the uncontainable and unacceptable. Thus, this paper argues that offering a critical approach to Catwoman as Hyde is the only way for freedom from social norms and offers independence from social conformity.

It is noteworthy that Kyle’s Hyde self is not about a tortured individual who seeks to redeem herself from her alter ego, but about accepting that separate self and releasing it from the confines of societal rules. In other words, Catwoman is the ability for humankind to negotiate life with a wild animalistic side. Catwoman’s fictional personality offers readers a chance to enter a new sphere of identity understanding. However, instead of untamed mayhem or total anarchy, Catwoman tests the limits of what life would be like without the rules and limitations of social rules. The tragedy of Stevenson’s novella is not the fall of a celebrity, but rather the fall of one of us. Jekyll is a friend and peer, not an estranged and obsessive recluse like Wayne. As such, Kyle is more like Jekyll—like all of us—in that she is a complex character torn between manifestations of good and evil. Catwoman, the Hyde-like heroic villain and villainous hero, and is one of the most humanistic comic characters of all.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Benjamin Syn for his continuous support and dedication to this project. This project would have been an impossible task without the help that Benjamin gave during the extent of the project. As this project has taken almost a year from topic idea to formulating a well-crafted research paper—Benjamin has been a vital aspect to the project. He often brainstormed, gave relevant insights into my argument, and often offered substantive feedback to this paper. Thank you Benjamin Syn for being an ongoing partner in my quest to finish my degree and my obnoxious desire to become a published writer. It is only because of Benjamin’s dedication—that I am who I am…I adore you and I thank you.

References

- Beatty, S (2004). Catwoman: The Visual Guide to the Feline Fatale. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- Brubaker, E (w); Cooke, D (a); Allred, M (a) . (2002). Catwoman: The Dark End of the Street. New York: DC Comics.

- Capitainio, A (2010). “The Jekyll and Hyde of the Atomic Age”: The Incredible Hulk as the Ambiguous Embodiment of Nuclear Power#8221;. Journal of Popular Culture 43(2): 249–270, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2010.00740.x

- Finger, B (w); Kane, B (a) . (1939). The Case of the Criminal Syndicate!. Detective Comics. New York: DC Comics. (27) Available at: http://www.comixology.com/Detective-Comics-1937-2011-27/digital-comic/10900 [Last accessed 10 December 2013].

- Madrid, M (2009). The Supergirls: Fashion, Feminism, Fantasy, and the History of Comic Book Heroines. United States: Exterminating Angel Press.

- Metz, C (1975). The Imaginary Signifier. Screen 16(2): 14–76, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.2.14

- Orr, P (1994). The Anoedipal Mythos of Batman and Catwoman. Journal of Popular Culture27(4): 169–182, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1994.2704_169.x

- Reichstein, A (1998). Batman—An American Mr. Hyde?. Amerikastudien/America Studies 43(2): 329–350. www.jstor.org/stable/41157373

- Stevenson, R L (1886). The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, Inc.. Available at: www.amazon.com/Strange-Case-D…ekyll+and+Hyde [Last accessed 10 December 2013].

_____________________

Lesa Syn is an instructor at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs and Community College of Denver. This article is reprinted from The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship.

Catwoman’s Hyde: A Comparative Reading of the 2002 Catwoman Relaunch and Stevenson’s Novella by Lesa Syn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License.

The Complicated Truth about Social Media and Body Image

by Kelly Oakes

Click here to read the article: “The Complicated Truth about Social Media and Body Image”

Everything You Need to Know About the Radical Roots of Wonder Woman

Her enigmatic creator believed women were destined to rule the world. 10 facts about the iconic heroine.

by Christopher Zumski Finke

#heroes #artsandculture #reportinginformation #history

All these things are true about Wonder Woman: She is a national treasure that the Smithsonian Institution named among its 101 Objects that Made America; she is a ‘70s feminist icon; she is the product of a polyamorous household that participated in a sex cult.

She comes out of the feminist movements of women’s suffrage, birth control, and the fight for equality.

Harvard historian Jill Lepore claims in her new book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, that Wonder Woman is the “missing link in a chain of events that begins with the women’s suffrage campaigns of the 1910s and ends with the troubled place of feminism fully a century later.”

The hero and her alter ego, Diana Prince, were the products of the tumultuous women’s rights movements of the early 20th century. Here are 10 essential elements to understanding the history and legacy of Wonder Woman and the family from which she sprung.

Wonder Woman first appeared in Sensation Comics #1 in December 1941.

Since that issue arrived 73 years ago, Wonder Woman has been in constant publication, making her the third longest running superhero in history, behind Superman (introduced June 1938) and Batman (introduced May 1939).

Wonder Woman’s creator had a secret identity.

Superheroes always have secret identities. So too did the man behind Wonder Woman. His name upon publication was Charles Moulton, but that was a pseudonym. It was after two years of popularity and success that the author revealed his identity: then-famous psychologist William Moulton Marston, who also invented the lie detector test.

William Moulton Marston was, as Jill Lepore tells it, an “awesomely cocky” psychologist and huckster from Massachusetts. He was also committed to the feminist causes he grew up around.

By 1941, Marston’s image of the iconic feminist of the future was already a throwback to his youth. He saw the celebrated British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst speak in Harvard Square (she was banned from speaking at Harvard University) in 1911, and from then on imagined the future of civilization as one destined for female rule.

Actually, the whole Marston family had a secret identity.

The Marston family was an unconventional home, full of radical politics and feminism. Marston lived with multiple women, including his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, a highly educated psychologist, and another lifelong partner, a writer named Olive Byrne, who was the niece of birth control activist Margaret Sanger. He had four children, two by each of the women, and they all grew up oblivious to the polyamorous nature of their parents’ relationships.

Marston, Holloway, and Byrne all contributed to Wonder Woman’s creation, a character that Marston explicitly designed to show the necessity of equality and advancement of women’s rights.

Wonder Woman was an Amazon molded from clay, but she was birthed out of feminism.

Princess Diana of Themyscira, or Diana Prince (Wonder Woman’s alter ego), comes from the land of the Amazons. In Greek mythology, the Amazons are an immortal race of beauties that live apart from men. In the origin story of Wonder Woman, Diana the is daughter of the queen of the Amazons. She’s from Paradise Island (Paradise is the land where no men live), where Queen Hyppolita carves her daughter out of clay. She has no father.

Wonder Woman has been in constant publication, making her the third longest running superhero.

She comes out of the feminist movements of women’s suffrage, birth control, and the fight for equality. When Marston was working with DC Comics editor Sheldon Mayer on the origins of Wonder Woman, Marston left no room for interpretation about what he wanted from his heroine.

“About the story’s feminism,” historian Lepore writes, “he was unmovable. ‘Let that theme alone,’ Marston said, ‘or drop the project.’”

Wonder Woman fought for the people—all the people.

The injustices that moved Wonder Woman to action did not just take place in the world of fantasy heroes and villains, nor was she only about women’s rights. She also fought for the rights of children, workers, and farmers.

In a 1942 issue of Sensation Comics, Wonder Woman targets the International Milk Company, which she has learned has been overcharging for milk, leading to the undernourishment of children. According to Lepore, the story came right out of a Hearst newspaper headline about “milk crooks” creating a “milk trust” to raise the price of milk, profiteering on the backs of American babies.

For the Wonder Woman story, Marston attributed the source of this crime to Nazi Germany. But the action Wonder Woman takes is the same as the real-life solution: She leads a march of women and men in “a gigantic demonstration against the milk racket.”

There’s a whole lot of bondage in Wonder Woman.

In the years that Marston was writing Wonder Woman, bondage was everywhere. “In episode after episode,” Lepore writes, “Wonder Woman is chained, bound, gagged, lassoed, tied, fettered, and manacled.” Even Wonder Woman herself expressed exhaustion at the over-use of being bound: “Great girdle of Aphrodite! Am I tired of being tied up!” she says.

She appeared on the first issue of Ms. Magazine, in 1972, with the headline “Wonder Woman for President.”

There’s little doubt that the sexual proclivities of the Marston family were in part responsible for this interest. A woman named Marjorie Wilkes Huntley was part of the Marston household—an “aunt” for the children, who shared the family home (and bedroom) when she was in town. Huntley was fond of bondage.

The theme was so persistent that an Army sergeant who was fond of the erotic images wrote to Marston asking where he could purchase some of the bondage implements used in the book. After that, DC Comics told Marston to cut back on the BDSM.

But that bondage was not all about sex.

The bondage themes in Wonder Woman are more complex than just a polyamorous fetish, though. Women in bondage was an iconic image of the suffrage and feminist movements, as women attempted to loosen the chains that bound them in society. Cartoonist and artist Lou Rogers drew many women in bonds, and Margaret Sanger appeared before a crowd bound at the mouth to protest the censorship of women in America.

Later, Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review would use a similar motif. One cover image had a woman chained to the weight of unwanted babies.

Readers—boys and girls—loved Wonder Woman.

Despite the political and secretive history of Wonder Woman’s creation, she was a wildly popular character. After Wonder Woman’s early success, DC Comics considered adding her to the roster of the Justice Society, which included Batman and Superman and many other male superheroes. Charlie Gaines, who ran DC Comics, decided to conduct a reader poll, asking, “Should Wonder Woman be allowed, even though a woman, to become a member of the justice society?”

Readers returned 1,801 surveys. Among boys, 1,265 said yes, 197 said no; among girls, 333 said yes, and only 6 said no.

But Justice Society was not written by feminist Marston. After Wonder Woman was brought into the Justice Society, she spent her first episodes working as the secretary.

The feminist spirit of Wonder Woman waned for decades.

After the death of William Moulton Marston in 1947, DC Comics took the feminism out of Wonder Woman and created instead a timid and uninspiring female character. “Wonder Woman lived on,” Lepore writes, “but she was barely recognizable.”

The first cover not drawn by the original artist, Harry G. Peter, “featured Steve Trevor [Wonder Woman’s heretofore hapless love interest] carrying a smiling, daffy, helpless Wonder Woman over a stream. Instead of her badass, kinky red boots, she wears dainty yellow ballerina slippers,” Lepore observes. Without her radical edge, Wonder Woman’s popularity waned until the rise of second wave feminism in the ’60s and ’70s, when Wonder Woman was trumpeted as an icon of women’s empowerment.

Wonder Woman became president.

In a 1943 story, Wonder Woman is actually elected President of the United States. Marston was adamant that a women would one day rule the United States, and that the world would be better when civilization’s power structures were in the hands of women instead of men.

Women in bondage was an iconic image of the suffrage and feminist movements.

Wonder Woman’s popularity soared as the feminist movement picked up in the late 1960s. Wonder Woman appeared on the first issue of Ms. Magazine, in 1972, with the headline “Wonder Woman for President.” At that time, Gloria Steinem said of Wonder Woman, “Looking back now at these Wonder Woman stories from the ’40s, I am amazed by the strength of their feminist message.”

The impact of Wonder Woman continues.

Wonder Woman is in for a great couple of years. Ms. Magazine just celebrated its 40th anniversary, and Wonder Woman is back on its cover. Jill Lepore’s book has been getting wonderful coverage (see her on The Colbert Report below discussing the kinks of the Marston Family), and Noah Berlatsky’s Wonder Woman: Feminism and Bondage in the Marston/Peter Comics will be published in January.

She’s also gearing up for her first-ever theatrical film appearance: Wonder Woman will appear in Zack Snyder’s 2016 film Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice. In 2017, she will be the star of her own film, to be directed by Michelle McClaren (Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead). Wonder Woman will be played by the Israeli actress Gal Gadot.

Let us hope that Gadot in the role conjures the spirit of the original creation of Marston, Holloway, and Byrne: a radical, independent, fierce woman and leader for all women and men to admire.

____________________

Christopher Zumski Finke blogs about pop culture and is editor of The Stake.

Everything You Need to Know About the Radical Roots of Wonder Womanby Christopher Zumski Finke is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

A Feminist’s Guide to Rom-Coms and How to Watch Them

by Ayu Sutriasa

Valentine’s Day is right around the corner, which means lots of chocolate, teddy bears, and single ladies being made to feel especially inadequate. Some might celebrate Galentine’s Day instead, some might skip on acknowledging the holiday at all, and some, myself included, will be holed up watching romantic comedies.

The internet is filled with lists of which rom-coms will “get you through” Valentine’s Day—the assumption seems to be that, otherwise, we singles would be festering alone in our living rooms, drinking vodka and singing “All By Myself” à la Bridget Jones. I enjoy the genre, but as a feminist I have some qualms.

Romantic comedies, particularly “the classics” of the genre, can be problematic by today’s standards of feminism. Movies like Pretty Woman and Princess Bride tend to perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes and romanticize men’s predatory behavior. Not to mention they are usually limited to depicting heterosexual relationships between an attractive cis man and an equally, perhaps even more, attractive cis woman. (LGBTQ folks: Here’s a list of rom-coms that drown out the heteronormative noise.) Lastly, if rom-coms are marketed to single women, then why are they mostly written and directed by men? (That’s a rhetorical question.)

Despite all this, rom-coms are stunningly popular. How do you reconcile your love of rom-coms with your staunch feminism?

Monique Jones, a pop culture critic and entertainment journalist, says that it’s OK if you like problematic rom-coms. “That doesn’t make us any less of an activist, it doesn’t make us any less down for the cause. It’s just being a human—and being part of a culture that has indoctrinated us to believe certain things, whether or not they’re true,” she says.

However, as feminists we do have to hold ourselves accountable, Jones says. Here are three tips on how to be a responsible rom-com consumer.

1. Be aware of how you’re internalizing the underlying messages

One of the biggest problems with the genre is that it tends to reinforce problematic ideas of romance. Contrary to rom-com plots, it’s actually not an outrageous notion for a man to love you “just as you are” (Bridget Jones’s Diary, Trainwreck, Pretty Woman, Grease), but it actually is outrageous for a man to consistently ignore your rejections and relentlessly pursue you (The Notebook, 10 Things I Hate About You, 50 First Dates, Breakfast at Tiffany’s).

“There are a lot of patriarchal things in society that we’ve grown up with that we’ve just assumed are normal. And those same ideals get stuck in these movies. That’s why so many of them don’t get called out as being problematic, even though they are indicative of larger problems in society,” Jones says.

Once you’re aware of the patriarchal underpinnings of these movies, you can more objectively decide what you believe is romantic. For example, maybe you don’t think it’s romantic to pretend to be someone’s fiancée while they are in a coma and have no idea who you are. It’s creepy, Sandra Bullock.

2. Be conscious of what/who you are supporting

This takes some research, but it’s worth it (IMDB will be your new best friend). Jones suggests learning what you can about the movie: Who’s the director? Who wrote it? Who acts in it? What’s the premise? “If you don’t feel offended, then I think it’s fine to watch,” Jones says.

And for the movies we don’t feel good about—like anything involving Woody Allen—consider skipping it. “I can’t justify having my head in the sand just to support somebody like Woody Allen,” Jones says. She skips anything with his name attached to it.

“I never liked his movies anyway. They don’t speak to me, first of all, as a woman, and second of all, as an African-American woman,” she says. “I know all the film critics and film students that I have been in contact with say that Woody Allen is a master at doing this and that. But I don’t align with anything that he does or is. And that’s how I go about it. If what the person does doesn’t align with my core values, then I just can’t do it.”

There are funnier, more romantic movies than Annie Hall, anyway.

3. Opt for rom-coms with fewer or zero problems

I know the classics are, well, classics, but why not watch a movie that takes a healthier approach to romance? “There are always movies that are smaller productions, and they might not have the big box-office dollars, but they’re still well-crafted, well-made movies,” Jones says.

Here’s a list of five from Thought Catalog to get you started: Warm Bodies, She’s Out of My League, Celeste and Jesse Forever, My Best Friend’s Wedding,and Kate and Leopold (sarcasm).

So, my fellow feminist rom-comphiles, don’t be discouraged.

There are still a lot of things people can enjoy about romantic comedies, Jones says. “With as much choice as there is out there, a person doesn’t have to give up their romantic comedy love altogether.”

____________________

Ayu Sutriasa is the digital editor for YES! Magazine. Her article is reprinted from YES!.

A Feminist’s Guide to Rom-Coms and How to Watch Them by Ayu Sutriasa is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Guardians of the Galaxy and the Fall of the Classic Hero

by A. David Lewis

A beautiful assassin. A superstrong thug. A star-lost child of the ‘80s. A sentient tree. A gun-toting raccoon. Meet the morally gray protagonists of Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy, the film that raked in $770 million at the box office this past summer and was just released on DVD.

Guardians, I’d like you to meet 20th-century mythology theorist Joseph Campbell. Trust me, you’ll have a lot to talk about.

…Oh, what’s that? You already know Mr. Campbell? Ah, that’s right, I’d forgotten: you beat the stuffing out of his heroic monomyth in your movie this year.

For those unfamiliar with the term: Campbell’s monomyth, also known as the “Hero’s Quest” or “Hero’s Journey,” is a narrative pattern derived from his extensive analysis of myths and stories from all around the world. In his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell outlines the pattern that nearly every “heroic” protagonist, going all the way back to ancient times, follows.

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

In other words, the protagonist is placed outside of his or her comfort zone, and, after toiling through various obstacles and setbacks, emerges to beat the bad guys and change the world for the better.

Since the trailer of its newest installment was released last week, think of the original Star Wars as an example. George Lucas had Campbell in mind when he created Luke Skywalker, farmboy turned rebel hero. Lucas even paid attention to the finer points of Campbell’s model, giving Luke a teacher (Obi-Wan), helpers (Han Solo, the droids), a magic talisman or weapon (the light-saber), and, most importantly, a moment that Campbell calls “the Abyss.”

It’s this Abyss – also known as “The Belly of the Whale” – that’s the low point in the monomythic cycle and vital to understanding what’s so notable about Guardians of the Galaxy. In the original Star Wars, Luke Skywalker experiences – all things considered – an “easy” low point: he’s sucked underwater in the Death Star trash compactor. In The Empire Strikes Back, things get a bit thornier: he gets his whole hand chopped off (rumored to be a plot point in JJ Abrams’s The Force Awakens) and plummets from Cloud City. Basically, if a hero doesn’t face an actual death, he or she has to (at least) deal with a metaphorical death before returning as a stronger, savvier version of himself.

But where was the Abyss moment in Guardians of the Galaxy? Was it when young Peter Quill loses his mother and is taken by aliens? Or, wait – maybe it’s when he’s thrown into that space prison and escapes? There’s also that moment when his team is nearly killed by an explosion in the Collector’s establishment. And Quill is all-but-dead when he leaves the safety of his ship to freeze and suffocate in exposed space while selflessly saving his teammate Gamora. And who can forget the scene when he is practically torn apart by wielding the Infinity Stone?

It’s as if Quill and his Guardians are running in loops around Campbell’s monomyth. Or, even better, the movie-makers are flagrantly disregarding it. They’re nearly satirizing it.

If audiences step back a bit, it’s easier to see how Guardians of the Galaxy might be a satire of the classic hero tradition. Villains are constantly interrupted mid-maniacal monologue, elaborate plans are impulsively overturned, and Quill, the movie’s closest thing to a hero, challenges the film’s protagonist to a dance-off. (Of course, there’s also the fact that two of the main characters are a tree and a raccoon!)

This is not to write off Guardians of the Galaxy and claim it’s a goof on Campbell’s model. Instead, it could be seen as a reaction to just how predictable, how tired, and even how broken the monomyth is today. The Guardians, remember, are just as much rogues as they are good guys. As Quill asks his team of misfits, “What should we do next: Something good, something bad? Bit of both?”

What Guardians of the Galaxy will do next – presumably in their Summer 2016 sequel – is continue to challenge our modern notions of heroism. Campbell’s monomyth was proposed just after World War II, at the dawn of the Cold War. It was a time when, in popular culture, the distinctions between heroes and villains were far more explicit.

Today, Quill and company are being presented to movie-going audiences at a time when when we’re distancing ourselves from old models – when we sorely crave a new pattern. The pure hero, the “white hat” of the old Westerns, is largely lost to us. Brilliant actors like Robin Williams and Phillip Seymour Hoffman are done in by their own personal ghosts, musicians like Amy Winehouse and Whitney Houston succumb to their addictions, and politicians – like the four Illinois governors who have been sent to prison – continue to disappoint. The Dark Knight perhaps said it best: “You either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”

The monomyth is making its final orbit. Heroes are so yesterday. Welcome, instead, to the tomorrow of the Guardians: characters who are a little good, a little bad, and more unpredictable than ever.

____________________

A. David Lewis is an Arts & Sciences Faculty Associate at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. He is the author of American Comic Books, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife, as well as the co-editor of both Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books and Graphic Novels, and Digital Death: Mortality and Beyond in the Online Age. His essay originally appeared in The Conservation.

Guardians of the Galaxy and the Fall of the Classic Hero by A. David Lewis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Me! Me! Me! Are we living through a narcissism epidemic?

by Zoe Williams

Click here to read the article: “Me! Me! Me! Are We Living Through a Narcissism Epidemic?”

Misinformation and Biases Infect Social Media, Both Intentionally and Accidentally

by Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia and Filippo Menczer

#argument, #causalargument, #cognitivebias, #ethos, #logos, #sharedvalues, #reportinginformation

Social media are among the primary sources of news in the U.S. and across the world. Yet users are exposed to content of questionable accuracy, including conspiracy theories, clickbait, hyperpartisan content, pseudo science and even fabricated “fake news” reports.

It’s not surprising that there’s so much disinformation published: Spam and online fraud are lucrative for criminals, and government and political propaganda yield both partisan and financial benefits. But the fact that low-credibility content spreads so quickly and easily suggests that people and the algorithms behind social media platforms are vulnerable to manipulation.

Explaining the tools developed at the Observatory on Social Media.

Our research has identified three types of bias that make the social media ecosystem vulnerable to both intentional and accidental misinformation. That is why our Observatory on Social Media at Indiana University is building tools to help people become aware of these biases and protect themselves from outside influences designed to exploit them.

Bias in the brain

Cognitive biases originate in the way the brain processes the information that every person encounters every day. The brain can deal with only a finite amount of information, and too many incoming stimuli can cause information overload. That in itself has serious implications for the quality of information on social media. We have found that steep competition for users’ limited attention means that some ideas go viral despite their low quality – even when people prefer to share high-quality content.

To avoid getting overwhelmed, the brain uses a number of tricks. These methods are usually effective, but may also become biases when applied in the wrong contexts.

One cognitive shortcut happens when a person is deciding whether to share a story that appears on their social media feed. People are very affected by the emotional connotations of a headline, even though that’s not a good indicator of an article’s accuracy. Much more important is who wrote the piece.

To counter this bias, and help people pay more attention to the source of a claim before sharing it, we developed Fakey, a mobile news literacy game (free on Android and iOS) simulating a typical social media news feed, with a mix of news articles from mainstream and low-credibility sources. Players get more points for sharing news from reliable sources and flagging suspicious content for fact-checking. In the process, they learn to recognize signals of source credibility, such as hyperpartisan claims and emotionally charged headlines.

Bias in society

Another source of bias comes from society. When people connect directly with their peers, the social biases that guide their selection of friends come to influence the information they see.

In fact, in our research we have found that it is possible to determine the political leanings of a Twitter user by simply looking at the partisan preferences of their friends. Our analysis of the structure of these partisan communication networks found social networks are particularly efficient at disseminating information – accurate or not – when they are closely tied together and disconnected from other parts of society.

The tendency to evaluate information more favorably if it comes from within their own social circles creates “echo chambers” that are ripe for manipulation, either consciously or unintentionally. This helps explain why so many online conversations devolve into “us versus them” confrontations.

To study how the structure of online social networks makes users vulnerable to disinformation, we built Hoaxy, a system that tracks and visualizes the spread of content from low-credibility sources, and how it competes with fact-checking content. Our analysis of the data collected by Hoaxy during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections shows that Twitter accounts that shared misinformation were almost completely cut offfrom the corrections made by the fact-checkers.

When we drilled down on the misinformation-spreading accounts, we found a very dense core group of accounts retweeting each other almost exclusively – including several bots. The only times that fact-checking organizations were ever quoted or mentioned by the users in the misinformed group were when questioning their legitimacy or claiming the opposite of what they wrote.

Bias in the machine

The third group of biases arises directly from the algorithms used to determine what people see online. Both social media platforms and search engines employ them. These personalization technologies are designed to select only the most engaging and relevant content for each individual user. But in doing so, it may end up reinforcing the cognitive and social biases of users, thus making them even more vulnerable to manipulation.

For instance, the detailed advertising tools built into many social media platforms let disinformation campaigners exploit confirmation bias by tailoring messages to people who are already inclined to believe them.

Also, if a user often clicks on Facebook links from a particular news source, Facebook will tend to show that person more of that site’s content. This so-called “filter bubble” effect may isolate people from diverse perspectives, strengthening confirmation bias.

Our own research shows that social media platforms expose users to a less diverse set of sources than do non-social media sites like Wikipedia. Because this is at the level of a whole platform, not of a single user, we call this the homogeneity bias.

Another important ingredient of social media is information that is trending on the platform, according to what is getting the most clicks. We call this popularity bias, because we have found that an algorithm designed to promote popular content may negatively affect the overall quality of information on the platform. This also feeds into existing cognitive bias, reinforcing what appears to be popular irrespective of its quality.

All these algorithmic biases can be manipulated by social bots, computer programs that interact with humans through social media accounts. Most social bots, like Twitter’s Big Ben, are harmless. However, some conceal their real nature and are used for malicious intents, such as boosting disinformation or falsely creating the appearance of a grassroots movement, also called “astroturfing.” We found evidence of this type of manipulation in the run-up to the 2010 U.S. midterm election.

To study these manipulation strategies, we developed a tool to detect social bots called Botometer. Botometer uses machine learning to detect bot accounts, by inspecting thousands of different features of Twitter accounts, like the times of its posts, how often it tweets, and the accounts it follows and retweets. It is not perfect, but it has revealed that as many as 15 percent of Twitter accounts show signs of being bots.

Using Botometer in conjunction with Hoaxy, we analyzed the core of the misinformation network during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. We found many bots exploiting both the cognitive, confirmation and popularity biases of their victims and Twitter’s algorithmic biases.

These bots are able to construct filter bubbles around vulnerable users, feeding them false claims and misinformation. First, they can attract the attention of human users who support a particular candidate by tweeting that candidate’s hashtags or by mentioning and retweeting the person. Then the bots can amplify false claims smearing opponents by retweeting articles from low-credibility sources that match certain keywords. This activity also makes the algorithm highlight for other users false stories that are being shared widely.

Understanding complex vulnerabilities

Even as our research, and others’, shows how individuals, institutions and even entire societies can be manipulated on social media, there are many questions left to answer. It’s especially important to discover how these different biases interact with each other, potentially creating more complex vulnerabilities.

Tools like ours offer internet users more information about disinformation, and therefore some degree of protection from its harms. The solutions will not likely be only technological, though there will probably be some technical aspects to them. But they must take into account the cognitive and social aspects of the problem.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on Jan. 10, 2019, to replace a link to a study that had been retracted. The text of the article is still accurate, and remains unchanged.

____________________