14

by Isabella Clowes, Elizabeth Dahlberg, and Katharine Miller

Abstract

The Hawaiian archipelago is vulnerable to climate change due to the low elevation and large population which is extremely reliant on the ocean, natural resources, and tourism. Native Hawaiians will suffer most from climate change because they depend on natural resources and reside on the coast. Climate change in Hawaii causes sea level rise, coastal erosion, tropical storms, and coral bleaching. To fix these issues, the entire planet needs to work together to reduce fossil fuels. However, Hawaii has implemented some strategies that have reduced the consequences of climate change.

Introduction

Our project addresses the main issue of how Native Hawaiians are being impacted by climate change. The main questions that guided our research were, what are the social, economic, and cultural issues the Native Hawaiians are facing? What are some solutions to help the Native Hawaiians?

Think of an island paradise with clear water, white sandy beaches, tall palm trees, and coral reefs, existing all in one place. This is Hawaii, a place anyone would dream of visiting. Now imagine all these things are damaged extensively by climate change. Hawaii faces this grim reality unless something is done to decrease the rate of climate change and mitigate the damages that climate change has caused in Hawaii. Climate change directly caused by humans has been getting worse since the industrial revolution (Murakami et. al, 2013). Humans rely on fossil fuels which spew out carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases which trap in the sun’s light. The air temperature rises causing coral bleaching, more extreme weather, and rising ocean levels as the ocean warms and expands (Murakami et. al, 2013). Warming of the oceans will harm fish populations and deprive residents who rely on fish for their income or diet (Cavenave & Llovel, 2010). The lifestyles of Native Hawaiians could significantly suffer in the near future as these problems continue to worsen.

Background

The first Hawaiians were descendants of Polynesian travelers originally from the islands of Tahiti and Marquesas (Andrade & Bell, 2011). During the 1820s, missionaries, Europeans, immigrants from the United States and Pacific, and ethnic groups from China, Japan, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Korea came to Hawaii. They created a different way of Hawaiian life, decreasing the Native Hawaiian populations. The native Hawaiian language was almost extinct, but the younger generations were able to keep it alive (Swenson et al., 2021). Tourism in Hawaii exploded, and Hawaiian culture was boosted into what we recognize today, creating festivals such as Lei Day and the Aloha Festival for tourism and profit (Andrade & Bell, 2011).

Being a set of secluded islands reliant on tourism with a unique culture, Hawaii is especially vulnerable to climate change. The main issues the islands face include sea level rise, increase in tropical storms, and coral bleaching, which put huge strains on Hawaiian society (Figure 2). Hawaii’s vulnerability is the reason why finding solutions to these problems is vital.

The issues created by climate change are experienced all over the islands, yet some residents will suffer more than others. Native Hawaiians are at a higher risk of suffering and loss from climate change because their religion and culture depend on natural resources (Ancheta, 2017). The traditional Native Hawaiian religion believes that all life originated from the ocean; therefore, they respect the ocean and rely on the life sustaining resources it provides (Andrade & Bell, 2011). People of other cultures in Hawaii do not have as significant ties to the ocean, allowing them to reside inland where the impacts of climate change are less severe (Ancheta, 2017). The decline of natural resources, and many pieces of Hawaiian culture create economic problems for Hawaii.

Tourism is an integral part of Hawaii’s economy as many tourists visit to connect with nature, lounge on beaches, explore the ocean, and experience the Native Hawaiian culture. Tourism in Hawaii greatly exploits the Native Hawaiian culture for profit which is detrimental and degrading to the people (Desmond, 1999). The image of an “ideal Native” is perpetuated with an exotic look and warm welcoming demeanor to appeal to tourists. Traditional clothing is sexualized and they are put on display as attractions. Despite the exploitation, Native people get sucked into the tourism industry because it offers many jobs as performers or tour guides. Native Hawaiians become reliant on the industry when they cannot find jobs elsewhere and it creates a cycle of ill treatment and dependence (Desmond, 1999).

Hawaii will lose much of the tourism industry as the beaches erode from sea level rise and tropical storms (Anlauf et al., 2011). It is reported that Hawaii earns about 60% of their tourism income off coral reef activities and recreation (NOAA, 2020). Coral bleaching and disappearing beaches will deter tourists, removing an integral part of Hawaii’s economy. Coral bleaching occurs when the ocean warms too much, forcing coral to spew out symbiotic algae that lives within its tissue and provides oxygen (Lirman & Schopmeyer, 2016). The coral is left colorless and more vulnerable to damage or disease after being bleached. Tropical coral reefs exist in warm water that regularly reaches temperatures above the maximum temperature of coral’s tolerance, therefore coral in Hawaii is much more susceptible to bleaching (Anlauf et al., 2011). Hawaii has already lost many of its reefs and it is predicted that the Earth might lose 70% of its reefs within forty years (Anlauf et al., 2011). Many fish species or other organisms such as lobster rely on the coral for food and protection (NOAA, 2020). Without healthy reefs, their populations suffer and there is less fish to catch, decreasing the food supply and income of fishermen.

One of the most severe and potentially deadly effects of climate change on the Hawaiian Islands is the increasing frequency of tropical storms and cyclones. Globally, the frequency of tropical cyclones is predicted to decrease while the average and maximum severity of tropical cyclones will increase (Murakami et. al, 2013). However, this prediction varies regionally. Climate models have predicted a statistically significant increase in tropical storms and cyclones that will affect the Hawaiian Islands (Murakami et. al, 2013). Tropical storms with their high winds and heavy rains are very hazardous and cause both loss of life and property damage. One of the largest hazards faced by Hawaiian’s during storms are falling Albizia trees, an invasive species to the Hawaiian Islands known for growing tall with brittle wood and shallow root systems (Ching et. al, 2020). In high winds these trees are very prone to dropping limbs or falling over causing large amounts of property damage and putting Hawaiians in danger. Flooding is another major problem caused by tropical storms as it can damage food and water supplies as well as infrastructure like roads and powerlines. Fast growing rural communities that have a large portion of Native Hawaiians are more vulnerable to tropical storms as lower income areas tend to have poorer quality houses, less robust infrastructure, and are generally closer to the coastal low-lying areas of Hawaii (Ching et. al, 2020).

Hawaii has implemented many strategies to reduce the effects of climate change and prepare to deal with the consequences, but they are still working to find more effective and less costly methods. Hawaii is making great strides towards reducing their dependence on fossil fuels and greenhouse gases. They are leaders in the fight against climate change and are creating a better future for their residents and the world.

Approach and Methodology

The approach to our problem began by researching how climate change specifically impacts Native Hawaiians and their culture. We conducted this research by looking at both primary and secondary sources like journal articles and government reports. The main search engine used was google scholar. Hawaii.gov was used to help find government reports on climate change issues, especially sea level rise and disaster preparedness. The main keywords used were “climate change”, “Hawaii”, “Native Hawaiians”, “coral reefs”, and “Hawaiian culture”.

The next step in our research was investigating problems caused by climate change in Hawaii. The main three issues we found were coral bleaching, sea level rise, and increasing tropical storms because they affect the social, economic, and cultural aspects of Hawaii. These are very important issues, and we wished to see how they would impact the Native Hawaiian community and what that meant for Native Hawaiian culture. First, we needed to collect background information on how climate change leads to these issues and how the issues directly harm Native populations. Our research was conducted through primary and secondary sources such as journal articles and government reports discussing these issues. We found these sources to gain firsthand knowledge into how communities are facing climate change and how their lives are being affected.

Our final topic of research involved finding solutions for Hawaii that would prevent more damage and help the Native residents retain their homes and livelihoods. We focused on finding cost effective solutions that would not disrupt the ecosystem or environment. The best solutions we found that fit our criteria were coral gardening and shoreline hardening. We conducted this research through primary and secondary sources by finding journal articles, reports, and studies on these solutions that explained the effectiveness of each solution.

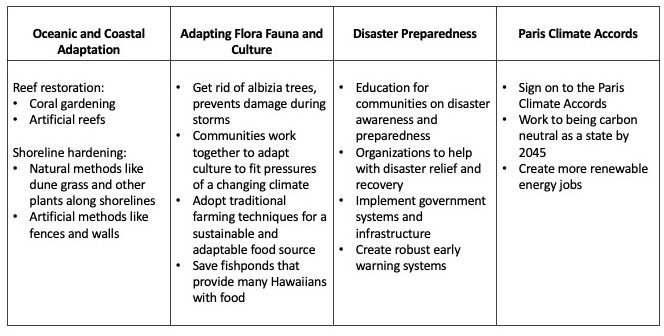

Throughout our research we found solutions that we determined were possible to implement in Hawaii. Pulling from the previous research, we brainstormed a large list of potential solutions. To determine the best solution to recommend, we organized our potential solutions into four categories: Oceanic and Coastal Adaptation, Adapting Flora, Fauna, and Culture, Disaster Preparedness, and Paris Climate Accords (Figure 3).

These solutions were then judged on how they would affect the community, how effectively they solved the problem, cost effectiveness, time of implementation, and scope. We quickly determined that the Paris Climate Accords category of solutions, which involved following the terms of the Paris Climate Accords and creating more renewable energy jobs was well beyond the scope of our project because Hawaii has already signed on to the Paris Climate Accords (Yu, 2018). Thus, this was a solution we did not need to recommend.

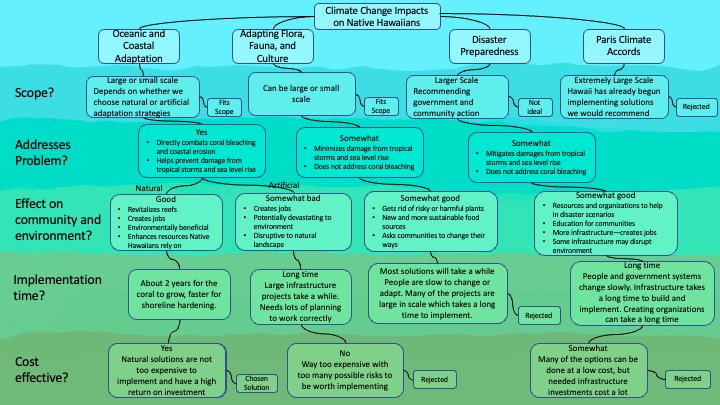

We dug up more in-depth information on the other three solution categories and led our peers through a project seminar and used their feedback as well as our solution assessment factors to determine the final solution we would recommend (Figure 4). The two primary solutions we focused on were coral gardening and shoreline hardening which made up our Oceanic and Coastal Adaptation solution category.

Recommendations

We strive to address how climate change is affecting Native Hawaiians and recommend a viable plan to fix these issues. Through research and analysis, we determined that Oceanic and Coastal Adaptation was the best suited solution to address the issues our project focused on. This solution combines coral gardening/restoration and natural shoreline hardening with minimal man-made objects.

Shoreline hardening combats coastal erosion and is used in several forms on most beaches and bodies of water. Different areas require different approaches including fences, stone or concrete walls, breakwaters and sills made of granite or other stone, or even plants such as dune grass and mangroves (Gittman et al., 2016). These structures prevent sand from being swept away by waves and storm surges. Erosion is such a big issue, and shoreline hardening is necessary to protect beaches, coastal property, and infrastructure. Man-made structures for shoreline hardening can sometimes cause more harm than protection to the coastal ecosystems (Gittman et al., 2016). If a structure is not engineered perfectly, it can alter the natural flow of the waves and cause more erosion down shore. These structures do not look pleasant on beaches, deterring tourists. We recommend a “living shoreline” to be implemented on Hawaiian beaches struggling with erosion. A living shoreline uses living, native plants to “harden” the shoreline and prevent erosion. Figure 5 shows the native plants that would provide the most effective living shoreline.

Dune grass is effective at holding onto sand and preventing it from being washed away with its root systems (Gittman et al., 2016). There are a few species of grass native to Hawaii that can tolerate the salt water and grow enough roots to effectively prevent erosion (U. Hawai’i Sea Grant Extension Service, 2004). Plants coupled with minimal fencing can enhance the hardening effect (Figure 6). Using only plants removes the risk of harming populations of sea turtles, crustaceans, birds and can enhance their habitat (Gittman et al., 2016). Another natural form of shoreline hardening is the restoration of coral reefs. We recommend Hawaii implements a way to restore coral reefs because they serve as a natural barrier against storm surges and prevent erosion.

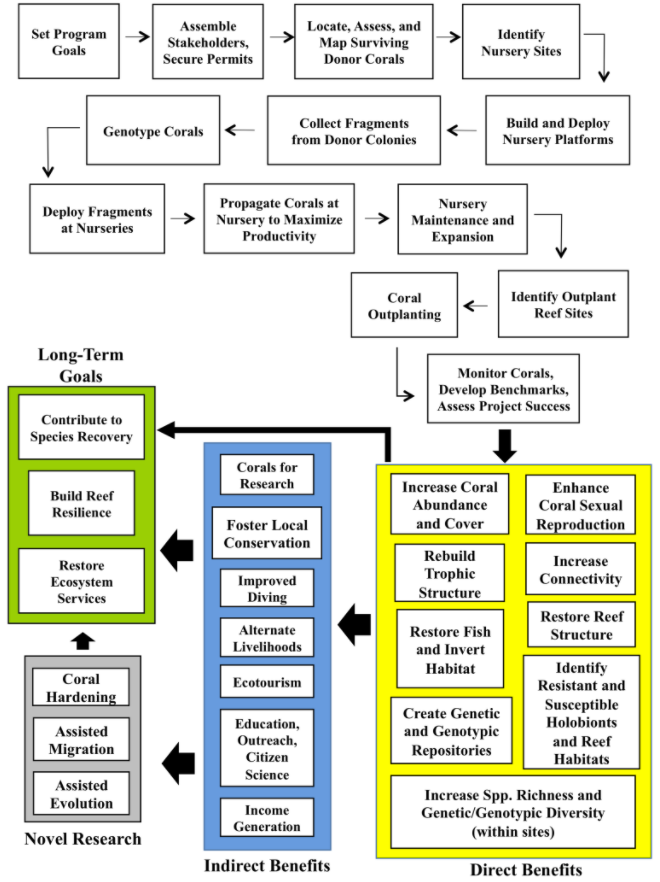

Coral gardening is a much newer approach to coral reef restoration. In the past, damage to coral reefs were fixed with engineering projects that required lots of experts and materials. The cost of these projects was huge and altered the natural beauty of reefs via artificial concrete and limestone structures (Lirman & Schopmeyer, 2016). This type of project was not reliable to restore the dying reefs all over the world therefore more economical and efficient methods of restoration came into popularity such as coral gardening. Figure 7 shows how coral gardening collects small coral fragments from struggling reefs and moves them into a nursery to be monitored and nurtured. Within a few years, the small pieces of coral grow and can be transplanted back into the dying reef to spread.

This method takes advantage of the asexual reproduction of corals, but encourages more sexual reproduction once the corals have been planted into the reef. The remaining corals living in a dying reef are too far apart to sexually reproduce. When the gaps are filled with gardened coral, they spread faster and thrive through sexual reproduction (Lirman & Schopmeyer, 2016). Coral gardening helps bleached reefs provide for organisms as a lively ecosystem once again. Reefs are a hot spot for marine activity and serve as a habitat for fish and invertebrate species by providing protection and food. The restoration of reefs in Hawaii would boost fish populations which Native Hawaiians rely on for food and income. Hawaii’s tourism industry depends on coral reefs, with reef activities bringing in about $304 million annually for the state (NOAA, 2020). Coral gardening is the best method to restore reefs while retaining their beauty and attraction by not adding man-made materials.

Implementation

Oceanic and Coastal Adaptation requires many elements to be implemented. Figure 8 describes the order in which to have successful implementation of coral gardening. Since coral reefs are important to tourism, it would make sense to get companies in the tourism industry involved in reef restoration. Major tourist hotels on the coast or scuba diving services could fund coral gardening and hire Native Hawaiians to perform the work. The indigenous people have more knowledge about the environment and corals than the average citizen and they are very invested in their local environments. These companies would profit off the restoration of reefs by attracting more tourists and could even find volunteers to do the work. To start the gardening process, areas with living corals need to be mapped and identified before collection. An area in the ocean to place the nursery with the best light and temperature needs to be selected. Figure 8 shows the indirect benefits coral gardening will have for the Native Hawaiian population.

For our plan to be implemented there would need to be an advisor to oversee the implementation and agree to the plan. Organizations, groups, and people in Hawaii who are focused on helping solve the issues of climate change would be great partners and possible stakeholders such as the Nature Conservancy, Hawaii Conservation Alliance, and Sunrise Movement. Preferably, a person of Native Hawaiian descent who is active in the Native Hawaiian community could oversee the project in order to unite these solutions with Native Hawaiian knowledge and empower the Native community. To start gardening, workers would have to be trained by an expert in corals to identify, collect, nurture, and transplant the coral. Once they are trained, the process of gardening should be relatively simple. The government could create a committee based on oceanic and coastal adaptation that focuses on successfully implementing solutions. Having government support could create many jobs for Native Hawaiians and they could share their knowledge of the land with the committee. This is not a short-term solution because the coral needs at least two years to fully grow before transplantation, but the possibility of seeing great changes in just two years creates hope for this solution. Shoreline hardening implementation is easier because it does not require constant maintenance as coral gardening does. An appropriate species of plant needs to be picked out that specifically meets the needs of the area and will be able to thrive under the specific conditions. Depending on the vegetation style chosen, the living shoreline may require additional pruning and landscaping throughout the year compared to other choices (U Hawai’i Sea Grant extension Service, 2004). A living shoreline project requires initial funds to purchase the plants and fencing but they are relatively low-cost. The government or private companies would need to provide wages to workers who plant and prune the living shoreline all across the Hawaiian coast.

Shoreline hardening’s success won’t be immediately visible since its goal is to prevent further erosion from taking place (Figure 9). Preventive solutions are difficult to judge because it is unknown if the solution has been beneficial or if it was just as effective as doing nothing at all. If shoreline hardening prevents major coastal erosion, this would be a success. To determine the success of hardening measures, it would take multiple years to measure the coastal changes year after year. Little or no change in the coast demonstrates successful results of shoreline hardening. The effectiveness of coral gardening is much easier to judge because, while it is a long-term solution, the final goal would be to restore Hawaii’s coral reefs to a point where they are able to thrive on their own despite the effects of climate change. The way to demonstrate success of this solution is to assess the health of Hawaii’s reefs after the gardening projects have begun. Oceanic and Coastal Adaptation is a solution that will take time to implement effectively, and it may be difficult to judge the success of such a long-term solution.

Conclusion and Broader Impacts

Coral gardening and shoreline hardening would utilize the natural resources to revitalize the environment that supports Natives Hawaiians. Natural resources such as fish and plants can prosper again, giving Native Hawaiians a source of income and livelihoods for their families. Coral reefs would be biodiverse again, serving as a hotspot for marine creatures. Beach erosion would not be a problem because of the natural barriers and Hawaii can adapt for the future. Tourism would continue as a booming industry giving Hawaii more abilities to become carbon neutral and keep their environment stable.

See Appendix 2 for the infographic used by the team on Project Presentation Day.

Bibliography

Ancheta, D. (2017, August 28). As climate change takes shape, fears over its threat to cultural resources grow. Hawaii News Now. Retrieved from https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/36018757/as-climate-change-takes-shape-fears-over-its-threats-to-cultural-resources-grow/

Andrade, N.N., & Bell, C.K. (2011). The Hawaiians. In Andrade N. & McDermott J. (Eds.), People and Cultures of Hawai`i: The Evolution of Culture and Ethnicity (pp. 1-31). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Anlauf, H., D’Croz, L., & O’Dea, A. (2011). A corrosive concoction: The combined effects of ocean warming and acidification on the early growth of a stony coral are multiplicative. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 397(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2010.11.009

Cavenave, A., & Llovel, W. (2010). Contemporary sea level rise. Annual Review of Marine Science, 2, 145-173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081105

Ching, A., Morrison, L., Kelley, M. (2020). Living with natural hazards: Tropical storms, lava flows and the resilience of island residents. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 47, 101546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101546

Desmond, J. (1999). Picturing Hawai’i: The “Ideal” native and the origins of tourism, 1880-1915. Positions: East Asia cultures critique 7(2), 459-501. https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-7-2-459

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Fisheries. (n.d.). Shallow coral reef habitat. Retrieved January 21, 2020. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/habitat-conservation/shallow-coral-reef-habitat

Gittman, R. K., Peterson, C. H., Currin, C. A., Joel Fodrie, F., Piehler, M. F., & Bruno, J.F. (2016). Living shorelines can enhance the nursery role of threatened estuarine habitats. Ecological Applications, 26(1), 249-263. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0716

Keener, V., D. Helweg, S. Asam, S. Balwani, M. Burkett, C. Fletcher, T. Giambelluca, Z. Grecni, M. Nobrega-Olivera, J. Polovina, & Tribble, G. (2018). Hawai‘i and U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Islands. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 1242–1308. https://doi.org/ 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH27

Lirman D, & Schopmeyer S. 2016. Ecological solutions to reef degradation: Optimizing coral reef restoration in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic. PeerJ 4:e2597 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2597

Murakami, H., Wang, B., Li, T. & Kitoh, A. (2013). Projected increase in tropical cyclones near Hawaii. Nature Climate Change, 3, 749-754. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1890

Swenson, J. P., Motteler, Lee S., & Heckathorn, J. Hawaii. In Encyclopedia Britannica, Retrieved 12 April 2021. https://www.britannica.com/place/Hawaii-state

University of Hawai’i News. (2018, November 28). Estimated $19B Damage of Hawaii by 2100, U.S. National Climate Assessment. University of Hawai’i Manoa. Retrieved from https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2018/11/28/hawaii-us-national-climate-assessment/

University of Hawaii Sea Grant Extension Service (2004). Erosion Management Alternatives for Hawaii. State of Hawaii, Department of Land and Natural Resources & Office of Conservation of Coastal Lands. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/occl/files/2013/08/dune-management.pdf

Yu, L. (2018, September 6). The Cost of Climate Change in Hawaii. Hawaii Business Magazine. https://www.hawaiibusiness.com/cost-of-climate-change/