Chapter 14-Forms of poetry

Poets write in either a fixed form or open form. Fixed forms are already established designs for poems that people choose to use for many reasons. Some of them are used over and over because they create beautiful sounds and pictures and rhythms. Sometimes a poet will like the immediate recognition of something as a sonnet or as an ode. Sometimes, the poet enjoys the intellectual exercise to see if he or she can make it work. Poets like to play around with language and have fun with it and making it fit into a certain form, but they may also feel they will be accepted by the establishment and by poetry lovers if readers can recognize that the poet uses some of the traditional forms. Sometimes the poet can get some respect or quicker recognition than poets who try more experimental forms. Experimental poets may take longer to get the recognition they want.

Open forms create their own ordering principles. They don’t have a set rhyme scheme or a set meter. The poet uses internal principles he or she created so their poem will sound a certain way or look a certain way. Open forms don’t follow already established principles. Blank verse uses iambic pentameter but does not rhyme. Free verse doesn’t use any particular meter or rhyme.

Fixed forms are organized by putting lines into groups called stanzas. Stanzas will have their own rhythm and system of end rhymes internal to that stanza that will then relate to the stanzas around it, so if different poets use the same system of organizing their stanzas and establishing their end rhymes, then they are using the same form. Rhyme schemes form an important part of any form. Most fixed forms have set rhyme schemes or several different rhyme schemes they can use, but rhyme schemes always refer to how end rhymes work, not internal rhyme. “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” has a set end rhyme scheme. it’s an ABBA end rhyme scheme and this is how rhyme schemes are always talked about by letters where they show the repetition of the rhyme so star in our rhyme high in sky rhyme star in our I’m again so it’s an a a b b a a

Rhyme scheme patterns are often referred to by the number of lines in the stanza, so a couplet has two lines, a tercet has three lines, a quatrain has four lines, an octave has eight lines. A Shakespearean sonnet has three quatrains, so three groups of four, followed by a couplet, one group of two. Three groups of four followed by the couplet forms a Shakespearean sonnet. Sonnets have two types: the Petrarchan or Italian sonnet, , and the Shakespearean sonnet, which is the English sonnet. Shakespeare did not create the English sonnet; he just made it famous as with so many things. A man named Petra created the Petrarchan, or Italian, sonnet. A Petrarchan sonnet contains eight lines, which is called an octave, and then six lines, called a sestet. Therefore, the Petrarchan sonnet has fourteen lines, same number as a Shakespearean sonnet. The lines are broken up for their rhyme scheme or their rhythm. Sonnets are generally in iambic pentameter, and a sonnet will always have a volta, which is a turning point. At the volta, the sonnet will change the tone or the topic or reverse the previous direction of the poem.

A villanelle has 19 lines of any length.

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas

This poem has five tercets and one quatrain. The villanelle form uses line repetition, and an ABA rhyme scheme until the one quatrain at the end where the rhyme scheme becomes ABBA. Notice the first line is also the sixth line and then repeats at the end of the fourth stanza and again in the quatrain at the end. Line repetition is prominent in villanelles. Rhyme schemes repeat and lines repeat. Then notice the last line of the first tercet comes in at the end of the third and then again at the end of the fifth tercet and then again at the end; another line which repeats. Imagine trying to create a work of art using this rhyme scheme, this number of lines, in this order, and then repeat and make sense of it. The poet has to enjoy an intellectual puzzle to create a villanelle.

The sestina also has a demanding fixed form. It has six, six-line stanzas.

Sestina

I saw my soul at rest upon a day

As a bird sleeping in the nest of night,

Among soft leaves that give the starlight way

To touch its wings but not its eyes with light;

So that it knew as one in visions may,

And knew not as men waking, of delight.

This was the measure of my soul’s delight;

It had no power of joy to fly by day,

Nor part in the large lordship of the light;

But in a secret moon-beholden way

Had all its will of dreams and pleasant night,

And all the love and life that sleepers may.

But such life’s triumph as men waking may

It might not have to feed its faint delight

Between the stars by night and sun by day,

Shut up with green leaves and a little light;

Because its way was as a lost star’s way,

A world’s not wholly known of day or night.

Song, have thy day and take thy fill of light

Before the night be fallen across thy way;

Sing while he may, man hath no long delight.

Algernon Charles Swinburne

Shown here are the first three stanzas and then the three-line conclusion or the “envoy.” A sestina is particularly demanding because the last word of each line in the first stanza must be at the end of the lines of each stanza. They don’t have to repeat in the same order, but they must be the same six words ending the lines in each stanza. The poem has “day” as the last word of the first line, the last word of the second line in the second stanza, and the last word in the third line of the third stanza. The writer of a sestina must repeat the ends of the lines. Then, those six words must appear in the envoy which contains only three lines. The poet must work them in, so the sestina is a demanding fixed form. poets like to play with these forms, and they don’t always use them perfectly. Sometimes they alter them a little bit, but they love to play with words. It is a mental challenge to write 39 lines in six stanzas and repeat those same six words in the right way.

The epigram is a short, pointed poem, often witty, satirical or paradoxical. Epigrams don’t have a prescribed pattern except to stay short and to rhyme.

There is a heaven, for ever, day-by-day

The upward longing of my soul tells me so.

There is a hell, I’m quite as sure, for pray

If there were not, where would my neighbors go?

Paul Dunbar

Dunbar makes a little funny, witty comment about his neighbors in the epigram.

Limericks are always light and humorous. usually not satirical, known for often being obscene. The limerick form lends itself to dirty rhymes. Most limericks are anonymous.

There was an old man with a beard

Who said, “It is just as I feared

Two owls and a hen, four larks and a wren

Have all built their nests in my beard!”

A limerick is five lines long with an AABB pattern, and they’re always just going to be silly or funny and light.

High school English teachers love to assign students to write a haiku, a Japanese form with only 17 syllables. It should have three unrhymed lines of five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables, and should create a picture.

After Basho

Tentatively, you

slip onstage this evening,

pallid famous moon.

Carolyn Kizer

It feels Japanese because it’s minimalist.

An elegy is a serious, meditative poem usually commemorating someone who has died. An elegy can commemorate an important event, such as a battle, but usually commemorating someone’s death. Elegies used to follow set pattern, but no longer have to. Walt Whitman wrote “O Captain! My Captain!” as an elegy to Abraham Lincoln after his death. This is only a small part.

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

Elegies often use apostrophe, where they address someone no present or something not alive. Whitman addresses a captain who is already dead and then talks about him. Commemorating Abraham Lincoln makes this an elegy, no matter what form the poem takes.

An ode is a serious lyrical poem, very formal, very high-minded and usually highly emotional. “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is one of the most famous and can be found in the online textbook. The parody humorously imitates another poem. One of the most famous American poems is “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Blanche Farley wrote a parody of “The Road Not Taken” titled “The Lover Not Taken.”

Committed to one, she wanted both

And, mulling it over, long she stood,

Alone on the road, loath

To leave, wanting to hide in the undergrowth,

This new guy, smooth as a yellow wood

Really turned her on. she liked his hair,

his smile. But the other, Jack, had a claim

On her already and she had to admit, he did wear

Well. In fact, to be perfectly fair,

he understood her. His long, lithe frame

Beside hers in the evening tenderly lay.

Still, if this blond guy dropped by someday,

Couldn’t way just lead on to way?

No. For if way led on and Jack

Found out, she doubted if he would ever come back.

Oh, she turned with a sigh.

Somewhere ages and ages hence,

She might be telling tis. “And I —

She would say, “stood faithfully by.”

But by then who would know the difference?

With that in mind, she took the fast way home,

the road by the pond, and phoned the blond.

The second poem imitates the first, trying to sound similar. A poet might take a famous poem and make a funny imitation, just as writers do with movies and songs.

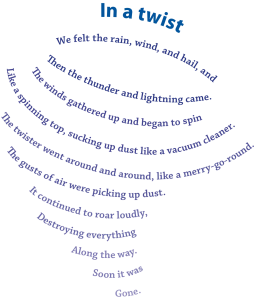

Too many fixed forms exist to cover in one chapter, so this chapter will end with the picture poem or shape poem. The poet of a picture poem arranges the words in such a way that they form a picture of what the poem is about.