9

Teacher Introduction:

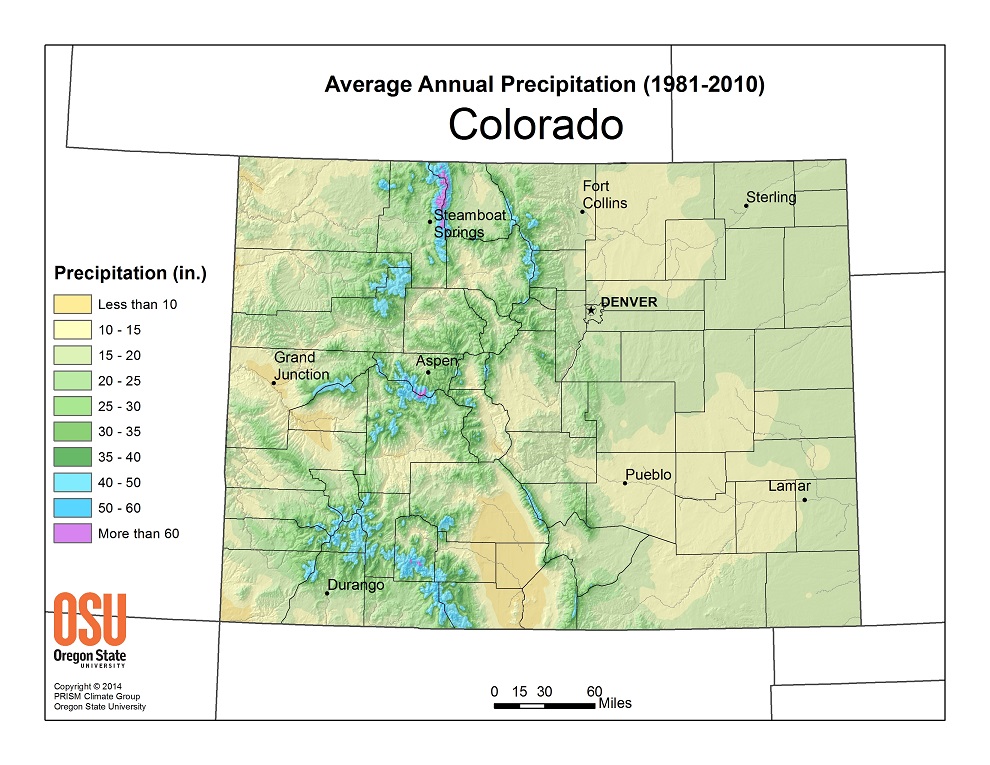

Most western states struggle to balance demand for with water with its limited availability. Except for some coastal areas, much of the West is an arid region. Colorado is no exception. Colorado has places, such as the Rockies, that receive much more precipitation than the rest of the state. Spots in the Rockies may receive up to 60 inches of precipitation per year. Much of Colorado, however, is plains territory, where the average annual precipitation may be only in the mid-teens. The Rockies create a rain shadow effect, meaning that the moisture is wrung from the atmosphere as air crosses the mountains from west to east. The ways in which water is dispersed throughout that state has affected how people have lived and worked in Colorado throughout its history.

Several major rivers are important to Colorado’s water story. The Arkansas and South Platte rivers run through eastern Colorado and flow onto the Plains. These bodies of water have acted as trails for humans and animals to follow. They are also essential to the agriculture of eastern and northern Colorado. In the West, the Colorado, Gunnison, and Uncompahgre rivers are among the many that support diverse agricultural endeavors. In the south, the Rio Grande, Animas, San Juan, and Dolores rivers supply water to farming and ranching enterprises. The tributaries of each of these rivers, such the Purgatoire, which joins the Arkansas, are also important to the land and economy.

Humans have rerouted or diverted existing waterways to suit their needs. The western side of Colorado has abundant access to water compared to the eastern side, yet the majority of the population lives east of the Rockies. Water diversion schemes have moved water from west to east to feed demand. The Colorado-Big Thompson Project is an example. A 13.1-mile tunnel diverts water from the Colorado River to the Big Thompson River, which serves northern communities on the eastern slope and Plains. Similarly, the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project diverts water from west to east. These ventures also are part of state-wide hydroelectric power projects. Sometimes communities from the western slope disagree with the redistribution of water to other places in the state as it reduces their own water supplies.

Colorado has been the center of controversies over water that has had far-reaching consequences for all water usage in the West. Water use in Colorado is defined by a law that supports prior appropriation. Basically, the first person to use a water source for something beneficial has a right to that water source. If several people claim the water, then the first person with the claim has the strongest stake. You don’t have to live near the water to be the claimant. Many rivers that feed other states originate or pass through Colorado. The state of Kansas once sued the state of Colorado over the amount of water Coloradans were taking from the Arkansas River. The Colorado River Compact is an agreement between seven western states and Mexico that outlines how Colorado River water will be allocated. Water does not recognize state borders; so Colorado has to work with other states and the federal government as it considers its water usage.

Water has also influenced Colorado history beyond its presence farming, ranching, and keeping people alive. Leisure pursuits such as skiing depend on the availability of water. The precipitation that falls in the form of snow during the winter melts to feed the rivers, lakes, and reservoirs that support boating and fishing in the summer. Blue Mesa Reservoir near Gunnison is the state’s largest body of water and a popular destination for people from inside and outside Colorado. Water is essential for life.

Sometimes we forget that the environment can shape history and change. The diversity in the availability of water and the way it is used in Colorado can be a way to think about history without focusing on particular people. Rather, place and resources are more important. Water also helps students think about how their use of resources might play a role in history.

The sources included in this chapter will help students explore the importance of water in Colorado’s history. Students might also begin to wonder about where water in our houses and schools comes from.

Sources for Students:

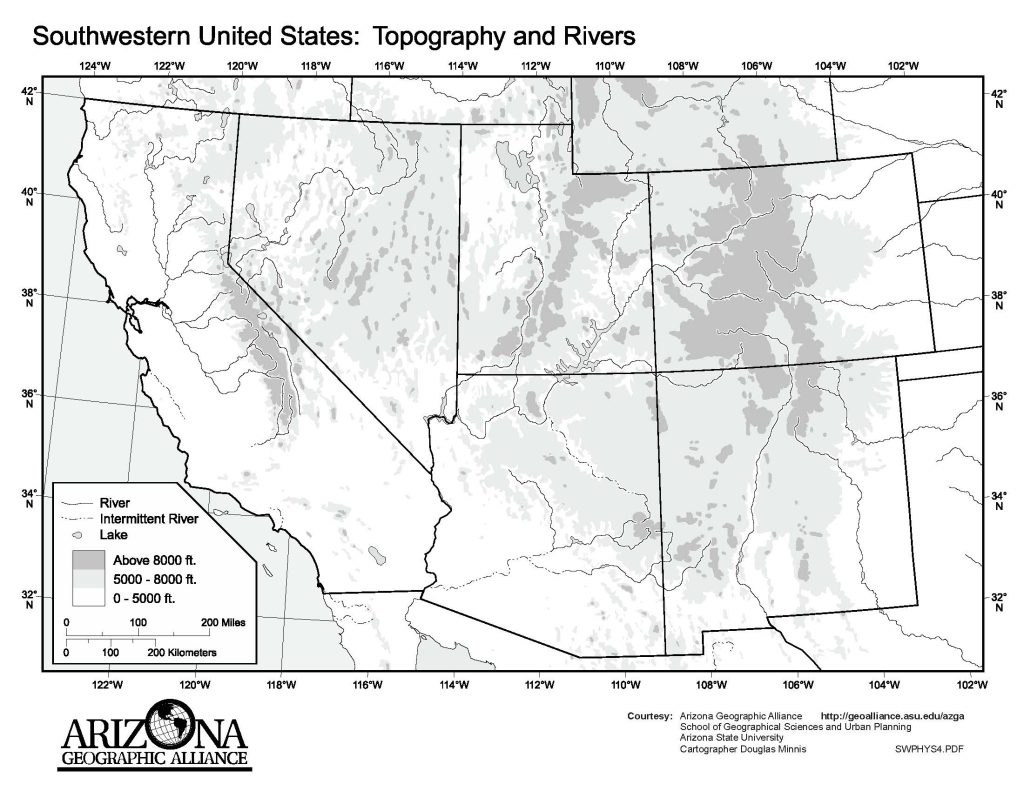

Document 1: Outline Map of the American Southwest with Rivers

[Source: Arizona Geographic Alliance. http://geoalliance.asu.edu/sites/default/files/maps/SWPHYS4.pdf]

Questions:

- Similar to the first map in Chapter 1, this outline map shows major rivers in Colorado and the Southwest. Take a moment to label Colorado’s major rivers on your map.

- The shading on this map will help you find the Rocky Mountains on this map. How does the Rocky Mountain range affect river flow?

- Place a star on your location on this map. What is the nearest major river?

- Does the drinking water in your school or home come from that river? How could we find out?

***

Document 2. Precipitation map of Colorado

This map shows how much rain and snow fall in Colorado during a year. The areas with cool colors have more precipitation and the areas with warm colors have less.

[Source: PRISM Climate Group: http://www.prism.oregonstate.edu/projects/gallery_view.php?state=CO]

[Source: PRISM Climate Group: http://www.prism.oregonstate.edu/projects/gallery_view.php?state=CO]

Questions:

- Check the Legend to review what the colors mean. Which parts of the state are dry and which are wet?

- What is the average precipitation in inches where you live?

- Why do you think some parts of the Colorado get more water than other parts?

- Which places have the most snow and rain, and which ones had the least?

- What kind of jobs do people need a lot of water to do?

***

Document 3: Cherry Creek Flood Memory

On August 3, 1933, the Castlewood dam broke. Dams hold back water. Heavy rain caused the dam to burst. The water rushed into downtown Denver and caused heavy damage.

“In 1933, there was no TV so you either read the newspaper or listened to the radio. We heard the news and the warning of a ‘wall of water’ coming down Cherry Creek. We went to West 7th Avenue and Speer Boulevard to watch the flood. It actually looked like a wall of water. Trees, branches, bushes, a dead cow and a dead dog floated by. The smell was unique to a flood and if you ever smell it you will never forget it. Awful! I was 10 years old and was very impressed.”

[Source: Leota H. Bostrom quoted in The Night the Dam Gave Way: A Diary of Personal Accounts. Castlewood Canyon State Park. p. 22.]

Questions:

- What could the person never forget?

- How did people learn about news and events in 1933?

- What did the person see in the water?

- Where did the person go to see the flood?

- How might places prepare for floods?

***

Document 4 & 5: Gold King Mine Spill

Miners use water to help them. Sometimes mines have material in them that are a danger to humans, animals, and plants. Water can move that unsafe material into streams and rivers. In 2015, toxic water from the Gold King Mine spilled into a creek. That creek flowed into the Las Animas river near Durango. The San Juan river was also polluted.

Photos of the Las Animas River

| Doc. 4 Photo before the spill | Doc. 5 Photo after the spill |

|

|

[Source: Photo at right by Josh Stephenson, Durango Herald. Available at: http://www.kunm.org/post/new-mexico-sue-epa-over-gold-king-mine-spill]

Questions:

- What’s different about these two photos of the same river?

- How might the fish and other aquatic life be affected by that new color?

- How can we clean up a river like the one on the right?

- Why, do you think, didn’t the mining company clean up poisonous chemicals before they spilled into the river?

***

Document 6: Irrigation

In the southern part of Colorado, water from a system of acequias or irrigation ditches has been used by farm communities. Sometimes, people in southern Colorado share water instead of having one person or a few people own it.

“San Luis Creek, heading in the Sangre de Christo range of mountains, has a length of thirty miles. Into it a dozen or more tiny creeks empty. There is one canal . . . six feet wide and seven miles long. On this creek and its tributaries, fifty-five farmers own sixteen thousand eight hundred acres, their area in no single instance being smaller than a section of six hundred forty acres, while three own over one thousand acres each, and one has three thousand seven hundred acres under fence as meadow and pasture land.”

[Source: Pabor, W. E. Colorado as an Agricultural State. Its Farms, Fields, and Garden Lands. (New York: Orange Judd, 1883). p. 128]

Questions:

- How long is San Luis Creek?

- How big is the canal that the farmers take water from?

- How many farmers are there on the creek and tributaries?

- How small is the smallest piece of land owned by a farmer?

- How large is the largest piece of land owned by a farmer?

- How might the farmers decide to share the water?

***

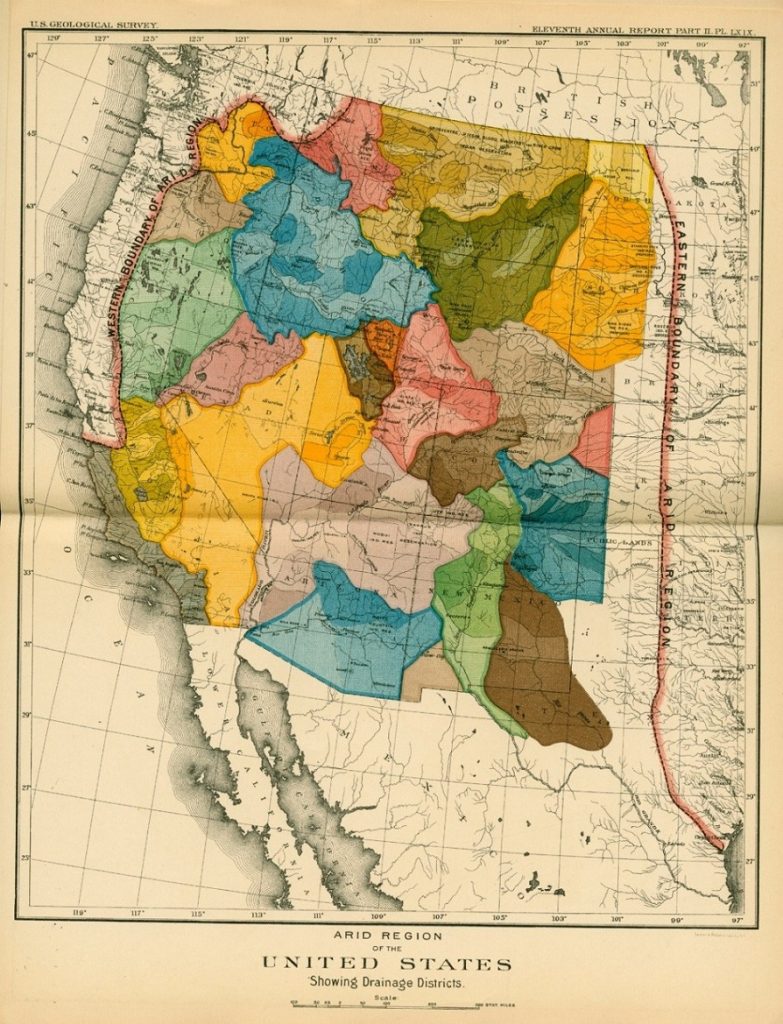

Document 7: Powell Map of the Arid Regions of the West, 1879

In 1869, John Wesley Powell led an expedition to explore the Green and Colorado Rivers which both begin in Colorado. Ten years after his exploration, Powell created this interesting map:

[Link to map online: http://www.mappingthenation.com/blog/a-radically-different-kind-o:-west/]

Questions:

- Find Colorado on this Map. (It might help to view an online version). Then notice the six different colored areas that Powell drew within the boundaries of Colorado. What might those colored areas refer to? (Remember that Powell was focused on water).

- How might life for farmers and ranchers have been different if Colorado (and other westerns states) had been created along these lines drawn by Powell?

- Most land in Colorado receives very little rain in the summer months. Where do Coloradans in August get water?

- Why do you think that new settlers in Colorado mostly ignored this map of Powell’s?

***

Document 8. Fishing

Lakes, reservoirs, rivers, and streams are all places where people fish in Colorado. Sometimes a government will put extra fish in these bodies of water so more people can fish.

“Special to the Press, Delta, April 30––It is reported that Tongue Creek, in Delta county, will be stocked into a fishing preserve. Tongue creek is stream where trout would do well, as it is free from reservoir waste waters and other disadvantages which would injure fish.”

[Source: “Tongue Creek Will Be Made Fishing Preserve is Report,” Montrose Daily Press (April 30, 1910), p. 3]

Questions:

- What is going to happen to Tongue Creek?

- Do you think this news is important to the people? Why or why not?

- Why would Tongue Creek be a good place for trout?

- How is a stream turned into a fishing preserve?

- What human activities could threaten the trout in Tongue Creek?

***

Document 9: Snow

A newspaper in Boulder county reported on this snowfall in 1926:

“BOULDER. March 26 —Silver Lake. 28 miles west of here, and source of Boulder’s water supply, had the heaviest fall of snow in Colorado this year, according to government statistics revealed here today. Twenty-one feet of snow has fallen during the past winter, the latest fall last night adding the final ten inches necessary to establish the record.”

[Source: “Lake Near Boulder Holds Snowfall Record,” Daily Times (Longmont), March 26, 1926, p. 1.]

Questions:

- Where does Boulder get its water?

- Where is Silver Lake?

- How much snow was needed in total to break the record for snowfall?

- What would be the total amount of snow for the record?

- During what time of year did the heaviest snowfall come?

***

How to Use These Sources:

Several of these sources present data that can be interpreted in more ways than the questions offered.

OPTION 1: The teacher might start by asking the students the ways they use water in their lives. Then they can talk about how water might be important to Colorado. Finally, ask them if they know where their water comes from.

Students can also label rivers any places that are mentioned in the sources. That map can also help students identify the nearest major river.

OPTION 2: Documents Two through Nine can help students explore some important ways that water matters. Students could start with that question – “How does water affect peoples’ lives in Colorado?” These sources offer some important reasons. The Cherry Creek memory selection might provide the opportunity for students to ask older friends and relatives if they have any memories of severe weather events.

OPTION 3: There are additional maps that help students begin to consider how Coloradans have tried to manage aridity in the state. Map Two is a good starting point here. Students might find a map of major population centers in Colorado. Then they could contrast that with Map Two. There are many possible issues to discuss here. Why did Coloradans settle on the eastern side of the Rockies and not the West? Remember the Gold Rush Map from Chapter One? When do settlers consider water availability? How might western slope residents (or those down river in other states) feel about water diversions from the Colorado River, for example, to the city of Denver?

The John Powell Map, Document 7, highlights another aspect of Colorado history. Students might consider why settlements did not follow Powell’s suggestion. What would life in Colorado be like if communities were organized around river basins?