6

William Bona IV; Holly Larson; and Hailey Oppenlander

How Twitter & Instagram Have Impacted Social Movements in the 21st Century

Introduction

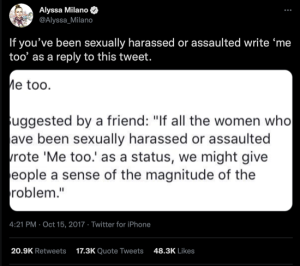

Two words — “Me Too” — prompted a long-awaited societal reckoning over sexual harassment and assault, beginning with the entertainment industry and echoing throughout the rest of society. While problems still persist, #MeToo seemed to make them at least more visible to those who hadn’t been paying attention all along.

Would these two words have spread as quickly or as widely without the corresponding hashtag on Twitter? How did Twitter’s complex system of posts, hashtags, and trending topics help catapult it to the top of its users’ feeds, putting the movement at the front and center of public discourse? And without those mechanisms in place, would the movement have gained the same amount of traction and prompted as many as it did to share their stories?

These are the types of questions that propel this chapter. We evaluate how the unique affordances and constraints of social media (specifically, Instagram and Twitter) influence how social movements operate in today’s world.

Both the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements existed long before their social media virality. The term “Me Too” was developed by Tarana Burke, a Black woman and activist, who had been working with victims of sexual assault for years. The Black Lives Matter movement initially took off in 2013 when George Zimmerman was acquitted after shooting and killing Trayvon Martin. The next year, the hashtag #Ferguson took off in response to the death of Michael Brown by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. In May of 2020, following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minnesota police, online unrest helped stir people to the streets with protests in at least 140 cities in the United States. Even though these movements existed before their online presence, today they are often seen as causes that relied heavily on the digital sphere to achieve a place of widespread discussion and acknowledgement in the United States.

But is this activism “real”? Or is it a mere performance of commitment? This chapter shows some of the ways activists deploy social media in support of social movements, some of the dismissals of these activities, and our own conclusion that the distinction between “online” and “offline” activism is no longer sharp.

The Reach of Hashtags

Log onto Twitter right now and you will be greeted with your home timeline, a collection of followed users and curated posts that make up the personalized side of the website. Scroll over to the trending tab, however, and you will be greeted with a cacophony of links, videos, news stories, and hashtags. These topics and posts are sorted by their popularity and interactivity (Scott 2015), and while many are categorized by key words and trending stories, the hashtag still remains the most important tool to reaching users outside of your personalized feed. The use of the hashtag was coined by Chris Messina in 2007 and described as an organic creation “by Twitter users as a way to categorize messages” (Scott 2015). Thus, even in its earliest stage, the hashtag served a unifying purpose in the communicative aspect of Twitter. Now, with the creation and implementation of advanced algorithms that can sort information from posts into trending topics shown to all users, hashtags are often relegated to fads of the day or week, with past trending hashtags disappearing from the trending page after a day or so. But while the permanence of the hashtag may be in doubt, its scalability, described by Boyd (2010) as the scalable level with which communication can reach individuals, is only limited by the number of users on the site. The functions of hashtags, retweets, likes, and trending topics allow for the dissemination of just about any message on the social media platform to any and every interested user. Thus, the affordance of the site to social movements is the possibility of the exponential growth of a message’s outreach. For instance, after Alyssa Milano’s call for the usage of the #MeToo, the term was tweeted over 1.7 million times within the first 24 hours of the post (Park 2017). And that is not even counting the number of users that saw the tweets, either as a result of its #1 trending status on the site at the time, or as a result of their personal timeline being flooded with victims and sympathizers. With days, a topic as meaningful and important as sexual assault and harassment was present in the feeds of millions of Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram users, prompting further coverage by national media corporations and even politicians. This wildfire-like spread of this message can be attributed largely to the functionality of the hashtag and other comparable social media tools.

Multimodal Affordances

Each social media platform delivers content in a unique way, certain content to be highlighted better or worse when it is distributed through a certain medium. Videos, for instance, spread with a greater scope through Twitter with their ability to be republished directly to a user’s main feed. Similarly, Instagram stories allow a republishing feature that can aid quick and rapid spread of videos. In this way, videos pertaining to the Black Lives Matter movement, such as the video of George Floyd’s murder that spread around social media, sparked outrage among the public at the violence that ensued by the officers. Videos like this one give the public a primary source of the terrible event and really show the gore of the violence, and spread exponentially online as more users interact with it.

Many activists on Instagram will insert data using an infographic, also known as PowerPoint activism (Ables 2020). In 2017, Instagram first allowed its users to post multiple photos at once, by using a “carousel post” method. With the ability to post up to ten photos at once, activists have been able to take advantage of this option in order to display information to users. This form of information display has been used to relay information on easy-to-understand concepts, such as mail-in voting, ways to help besides posting on Instagram, and relaying statistics.

The key to a viral social media post is getting on the right side of any site’s algorithm. Becoming increasingly complex as people use social media sites more and more, algorithms are used on all websites to filter content to the viewer. For instance, Instagram’s “explore” page will show posts similar to ones you have interacted with in the past. On the creator side, the more people interact with your post, the more that it will be promoted. It works exponentially, as more people are able to see your post, more will interact, and in turn even more people will see and interact with that post. On Twitter, once a post makes it to a trending page, everyone will see it and it will blow up. Sometimes it can just be luck. It is for this reason that movements like the Me Too Movement, and the Black Lives Matter Movement, existed for years before they became viral online. The key to virality is to get on the right side of the algorithm.

Despite the many ways that social media are utilized for impactful social change, some media can be used to relay misleading information. With social media, any person can post whatever they please, and their intentions are not always clear. Social media are used heavily by users across the board to promote their personal political intentions, and it is not rare for facts to be exaggerated or even fabricated for that purpose. Many users also will promote information that they believe to be true, but they may be ill-informed. As former president Donald Trump would call it, “fake news,” no matter what your political standing, is rampant and present online.

Limited Cost to Action

In evaluating the affordances and constraints of new media, sometimes it becomes easy to conceive of affordances as benefits and constraints as cons. But can the capabilities of social media hinder certain types of positive activities?

Once you have purchased the devices needed for social media communication, there is little cost to you for each communicative action thereafter. For example, if you’ve already purchased a phone and Wi-Fi or cellular access, writing three Tweets can occur at little loss to you other than minimal time lost (and perhaps some mental strain at trying to think of the best, wittiest thoughts to share). But what does this mean for social movements utilizing social media? Can an affordance — ease of sharing and posting — be detrimental for social movements?

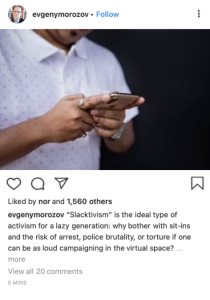

Some people argue that the convenience of liking, sharing, and posting online enhances the ability of people to feel involved in social movements without effectively putting their bodies on the line. Having such an “easy” way to engage with social movements has led to the term “slacktivism,” which paints a picture of lazy supporters who claim to be behind a cause simply by sharing a post on social media, even though they don’t engage with the cause in any other way (Morozv 2009). The term comes from “slacker” and “activism” and is particularly used to refer to the realm of social media (Glenn 2015). Writer Evgeny Morozov states in an NPR opinion article, it is a “feel-good online activism that has zero political or social impact” that “gives those who participate . . . an illusion of having a meaningful impact on the world without demanding anything more than joining a Facebook group.”

In a 2010 piece for the New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell argues that this illusion means that society has “forgotten what activism is.” He attributes this to the mechanics in which social media operate, consisting of weak ties between users and networks rather than structured organizations. Due to this, Gladwell claims, “It makes it easier for activists to express themselves, and harder for that expression to have any impact.” From this perspective, social media is diluting the potential of “real” activism to make lasting change to society.

Others, however, argue that what Gladwell and other scholars define as “real” activism is actually just an older (and still utilized) form of activism. In a response to Gladwell’s article, Joseph Ting (2010) notes how online activism in China is not a kind of lazy, removed, semi-involvement that others paint it to be. Rather, this activism carries bodily danger for participants and even led to a Nobel Peace Prize for one of the activists, Liu Xiaobo. This blurs the line between “online” versus “offline” or “real” activism. To further complicate the idea of activism as being either “online” or “offline,” the Posts Into Letters campaign utilized by March for Our Lives (a movement against gun violence in schools) takes social media posts and converts them into letters sent to Congress, all in the handwriting of a student who died in the Parkland school shooting. The project website notes that 96% of Capitol Hill staff claim that letters are the best way to make an impact on politicians.

Though Gladwell points out important observations about weak ties and networks in social movements on social media, he seems to fall slightly into a “moral panic” viewpoint by painting in-person demonstrations as the only valid type of activism. James Dennis (2019) notes that regarding activism, “there has been a return to the utopian-dystopian dichotomy that bedeviled the social science of the Internet during the 1990s.” Dennis claims that rather than clear binaries between digital and nondigital spaces, or active and inactive involvement, there is actually a “continuum of participation,” and the success of social movements is not always quantifiable. Brie Rogers Lowery, Director of Change.org in the United Kingdom, claims that today’s digital landscape opens up opportunities for everyone to get involved in important political and social justice conversations of their day and make change. In a TEDx Talk, Rogers Lowery (2013) gives the example of Dom Aversano, a man who created a petition to hold Secretary of Work and Pensions, Iain Duncan Smith, to his statement that he could live on £53 per week. “He showed that with a laptop and an idea, the web can deliver authority to anyone,” she says.

In addition, the Save Darfur Cause, in light of genocide occurring in Sudan, was one of the largest social movements known to Facebook at the time. Facebook was used for recruitment and fundraising purposes, as well as to spread awareness. According to Lewis, Gray, and Meierhenrich, the Save Darfur movement on Facebook had over a million members, although 99.76% of members never donated to the cause. Therefore, although the movement had significant scope online, most of the financially impactful activism came from a select few people called “hyperactivists.” Therefore, in analysis of the Save Darfur case, online activism resulted in hundreds of thousands of dollars of donations, even though very few people in the end contributed to the cause outside of online interactions.

These examples show that social media can simultaneously help causes become successful while also allowing some users to engage in superficial ways that do not lead to change. Social media allows users to showcase and curate a certain presentation of self (Bucher 2012; Jones & Hafner 2021). In some instances, users supporting a cause online may do so more for the sake of how it looks or how it fits into their presentation of self, rather than be motivated by the cause itself or the desire to make change. This is often referred to as performative activism or performative allyship. Kalina (2020) describes performative allyship online as “a virtual pat on the back” and affirmation of one’s benevolence rather than an action focused on creating change. For Forge, Phillips (2010) writes that performative allyship online is usually characterized by simplicity, anger directed towards a vague antagonistic force, and feel-good benefits for the poster.

Many people say that an example of performative activism is #BlackoutTuesday. The trend began (Jennings 2020) as #TheShowMustBePaused, created by Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, two Black women who wanted to bring light to racism within the entertainment industry. However, many people on Instagram began posting black squares with the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter, meaning that it was these black squares that showed up when users then tried to search the hashtag. Activists noted that this action was actually harmful to the cause, as it prevented people from viewing resources that had previously been attached to the hashtag. In an interview with Vox, Black feminist writer Feminista Jones says about the participants in #BlackoutTuesday:

Especially when social movements are “trending” online, users may post as a low-stakes way of expressing support without thinking about how people rely on social media for resources and information regarding social movements. Kalina writes, “After these posts, just continuing on with our lives and posting photos of what we had for dinner, or of our super cute dog, is not helpful” (478). In these situations, it appears as though “activism” is serving more as a means of phatic communication than as activism. Wang, Tucker, and Rihill (2011) define “phatic technology” as one that “establish[es], develop[s] and maintain[s] human relationships. Jones and Hafner (2021) write that in phatic communication, “often the ‘content’ is not the point of this kind of communication; connection is” (102). When users repost a graphic on Instagram with the picture of yet another Black individual who has died from police violence, or share a news headline about the acquittal of another white man who killed a Black person, their focus may be on affirming their identity as a “good person” and making that known to their followers. Kalina posits that in performative activism, “allyship does more for you than for the people it professes to help” (479). Resharing posts or using a hashtag can affirm that you support certain causes. Silence can be read as disinterest in justice: “People go along with the trend, feeling they must force being an ally; fearing their reputation, being called out, or ‘unfollowed’” (479), Kalina says.

Low-Cost Controversy

While some perform their support for popular, or niche, causes, others can manipulate social media campaigns through the risk-free use of denigration or opposition.

The anonymity of social media platforms has made it easier for some to oppose social movements and enhance controversy. For instance, in response to Black Out Tuesday, right-leaning users on Facebook began other movements such as “Blue Lives Matter,” to affirm the role of police officers and take light away from the Black Lives Matter movement. This effect is referred to as the online disinhibition effect (Belk 2013). The disinhibition effect is the lack of restraint that one may experience when speaking online due to the anonymity and lack of eye contact. A poll released in July by the Cato Institute concluded that 62 percent of Americans agreed with the statement “The political climate these days prevents me from saying things I believe because others might find them offensive,” with responders identifying as 77 percent of self-identified conservatives and 52 percent of liberals. This effect can lead to a toxic environment for social media activism.

Micro-Level Uses of Social Media for Movements

Dennis (2019) notes that oftentimes critics of social media activism focus solely on large-scale movements: “the slacktivist critique focuses on the macro-level as the arena in which power is contested and exercised.” However, we posit that scholars must consider how social media is leveraged within smaller communities and smaller causes in order to fully evaluate how it is influencing activism today.

As students at the University of Notre Dame, we reached out to one of the organizers behind the queerjoynd Instagram account. This movement relied on online strategy heavily to promote their cause on campus, which aimed to create a community of joy and assert the validity of queer presence on Notre Dame’s campus in response to a homophobic article published in a campus newspaper. In an interview, this organizer noted the importance of utilizing existing networks, using social media for information-sharing in localized contexts, and reckoning with the pros and cons of user engagement towards social movements on social media.

The queerjoynd account had been used for a few different causes. The first was in 2020, a petition asking for Fr. Jenkins to resign after he caught COVID at the Rose Garden. The second was a protest against Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination. In 2021, they changed the account name to queerjoynd and began posting new content, with the old posts either archived or deleted. This allowed them to keep their same followers, which was vital to getting the news out about their campaign on campus. When the account was created, the organizer began by following people from accounts they followed that seemed progressive, such as a meme page called ndforgays. By relying on existing networks of users with similar beliefs, they did not have to “recreate the wheel” for this current campaign.

The organizer felt that social media was a great way to get information out to the student body at the mid-sized university. “It’s a really great way to keep people updated quickly,” they said. They also noted how the affordances of social media such as link-sharing make it easier for students to sign a petition or read an article than seeing a QR code or link on a poster around campus. “It’s also a great way to share links and things,” they said. “But it’s a lot easier to do it on social media, when someone can just click immediately and get access to whatever information you want to share with them.” The organizer mentioned that they were able to use Instagram to share articles they had written for the student newspaper that further elaborated their causes’ beliefs.

Since the campaign was just for the university community, this seemed to make social media an even more vital aspect of the cause, even if significantly less people than followers showed up for the in-person event. “In localized contexts, that works really well, because it’s a great way to share information quickly,” they said. “And you don’t have to have a bunch of followers for it to be effective. Because I think that the people that you do get do tend to be more involved when you’re in a local or grassroots context as opposed to a national law movement.” The organizer said that because Instagram doesn’t have an event feature like Facebook, it can be hard to guess how many of the followers are going to show up to the in-person event associated with the campaign (which occurred for both the ndagainstacb and queerjoynd manifestations of the account).

Though they recognized the vital role of social media in their campaign, the organizer expressed some concern about the way social media in general has come to be used in activism. “It’s a difficult balance to strike, because the Instagram infographic industrial complex is definitely something that has been built up in the past two, three years,” they said. “It’s like, I posted all the things on my story, but I didn’t change a single thing about the way that I lived my life.” The organizer also noted how there seems to be almost a “groupthink” element at play in the way that people feel pressured to post these graphics on their stories in order to not be labeled a “bad person,” yet this hasn’t necessarily led to political or societal change.

Conclusion

Social media’s unique affordances and constraints impact the way that users interact with social movements. Though some see a clear division between the in-person sit-ins of days gone by and the online “slacktivist” efforts of many supposed allies today, we find that the distinction between “online” and “offline” and the attempt to define a “real” activism is not productive. Instead, we should pay attention to the ways in which aspects of social media like algorithms, hashtags, and low cost to action can simultaneously help or hinder specific social movements depending on their locational context and how users interact and engage with them.

References

Ables, Kelset. 2020. “Selfies and sunsets be gone: The latest Instagram trend is PowerPoint-style presentations” Accessed December 4, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/08/15/instagram-race-activism-slideshow-graphics/

Aversano, Dom. 2021. “Iain Duncan Smith: Iain Duncan Smith to Live on £53 a Week.” Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.change.org/p/iain-duncan-smith-iain-duncan-smith-to-live-on-53-a-week.

Belk, Russell W. 2013. “Extended Self in a Digital World.” Journal of Consumer Research 40, no. 3): 477–500. https://doi.org/10.1086/671052.

Bucher, Taina. 2012. “Want to Be on the Top? Algorithmic Power and the Threat of Invisibility on Facebook.” New Media & Society 14 (7): 1164–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812440159.

Burke, Tarana. 2021. “I Founded ‘Me Too’ in 2006. The Morning It Went Viral Was a Nightmare.” Time, September 24, 2021. https://time.com/6097392/tarana-burke-me-too-unbound-excerpt/.

Change the Ref. n.d. “About this Project.” Accessed November 30, 2021. https://postsintoletters.com.

Dennis, James. 2018. Beyond Slacktivism: Political Participation on Social Media. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2010. “Small Change.” New Yorker, September 27, 2010. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell.

Glenn, Cerise L. 2015. “Activism or “Slacktivism?”: Digital Media and Organizing for Social Change.” Communication Teacher 29 (2): 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2014.1003310.

Jennings, Rebecca. 2020. “Who Are The Black Squares and Cutesy Illustrations Really For?” Vox, June 3, 2020. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/6/3/21279336/blackout-tuesday-black-lives-matter-instagram-performative-allyship.

Jones, Rodney H. and Christoph A. Hafner. 2021. Understanding Digital Literacies. Philippines: Routledge.

Kalina, Peter. 2020. “Performative Allyship.” Technium Social Sciences Journal 11: 478-481. https://techniumscience.com/index.php/socialsciences/article/view/1518.

Lewis, Kevin, Kurt Gray, and Jens Meierhenrich. 2014. “The Structure of Online Activism.” Sociological Science 1 (1): 1-9. https://sociologicalscience.com/download/volume%201/february_/The%20Structure%20of%20Online%20Activism.pdf.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2009. “Foreign Policy: Brave New World of Slacktivism.” NPR, May 19, 2009. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104302141.

Papacharissi, Zizi, and Danah Boyd. 2011. “Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications.” A Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites, Routledge, New York, pp. 39–58.

Phillips, Holiday. 2020. “Performative Allyship Is Deadly (Here’s What to Do Instead.)” Forge, May 9, 2020. https://forge.medium.com/performative-allyship-is-deadly-c900645d9f1f.

Rogers Lowery, Brie. 2013. “The Authority of Anyone: Brie Rogers Lowery at TEDxHousesofParliament.” Filmed June 2013 at TEDxHousesofParliament, London, UK. Video, 7:58. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c7HdwEvAIgw.

Scott, Kate. 2015.“The Pragmatics of Hashtags: Inference and Conversational Style on Twitter.” Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 81, May 2015, pp. 8–20., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.03.015.

Ting, Joseph. 2010. “On Slacktivism.” New Yorker, October 18, 2010. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/25/on-slacktivism.

Wang, Victoria, John V. Tucker, and Tracey E. Rihll. 2011. “On Phatic Technologies for Creating and Maintaining Human Relationships.” Technology in Society 33, no. 1-2: 44-51. https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.library.nd.edu/science/article/pii/S0160791X11000182.