Introductions and Conclusions

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Identifies components of an effective introduction, body, and conclusion and how to organize

What Is Arrangement?

Arrangement is the organization and structure of ideas in your essay. Choosing the right structure depends on the application of critical thinking for your purpose. At times, the arrangement is specified by an assignment or suggested by clues for a given topic. However, all essays, regardless of the pattern of development, should have an introduction, body, and conclusion.

The Introduction

The introduction is the first paragraph of an essay and plays an important role in writing an effective paper. The goals of the introduction are to introduce the topic, to provide background about the topic, and to establish the main idea, purpose, and direction. The introduction has three essential parts, each of which serves a particular purpose: the hook, relevant background, and thesis statement.

- The Hook—The hook engages your reader’s interest. It can be in the form of a question, a quote, an anecdote or story, an interesting fact, or an original definition.

- Relevant Background—Background information creates context by providing a brief overview. This information helps readers see why you are focusing on the topic and transitions them to the main point of your paper.

- Thesis Statement—The thesis statement expresses the overall point and main ideas that will be discussed in the body. It usually appears as the last sentence of the introduction and is usually one sentence.

What NOT to do in an introduction

- Do not apologize. Avoid phrases such as “in my opinion” or “I may not be an expert but…” These phrases imply that you really don’t know your topic.

- Do not announce what you intend to do. Never begin with phrases such as “In this paper I will…” or “The purpose of this essay is to…” Your introduction should establish the intention and purpose of the essay.

- Do not begin with a dictionary definition. Avoid beginning your essay with phrases such as “According to Webster’s Dictionary…” This method is overused and unoriginal. Create your own to show a relevant context for your essay.

- Do not be too vague. Avoid irrelevant comments and digressions. Stay focused.

Body

The body paragraphs are a collection of paragraphs related to your topic that provide supporting evidence for your thesis statement. Each body paragraph should be unified, coherent, and well-developed with a specific pattern of development. A paragraph is unified when each sentence relates directly to the main idea of the paragraph which is stated in the topic sentence. A paragraph is coherent if the sentences are logically connected. Coherence can be accomplished by repeating key words and using transitions to show logical sequence. Review the attached list of transitional words and phrases.

Body paragraphs should contain three structural components: the topic sentence, supporting sentences, and the concluding sentence.

- Topic Sentence—The topic sentence is usually the first sentence in the paragraph. It indicates what the paragraph will discuss and guides the writer and reader. The writer will know what information to include or exclude, and the reader will understand what the paragraph will discuss.

- Supporting Sentences—Supporting sentences provide examples or facts to support the topic sentence.

- Concluding Sentence—The concluding sentence summarizes the information to show unity within the paragraph.

What NOT to include in the body paragraphs

- Do not include irrelevant information. Material that does not relate to the thesis should be deleted.

- Do not include general or vague information. Specific examples, clear reasons, and precise explanations communicate your ideas to readers

- Do not under-develop supporting details. Determining how much support is needed depends on the scope of your thesis statement, audience, and purpose.

Conclusion

The conclusion is the final paragraph of the essay and plays an important role in writing an effective paper. The conclusion should reinforce your thesis statement and purpose by reiterating the thesis statement and providing a sense of completeness about the essay’s topic. An effective conclusion will summarize your essay and provide a final comment about your topic. There are several strategies that are helpful in writing a conclusion:

- Review key points

- Link the concluding paragraph to the introduction by reiterating a word or phrase

- Recommend a course of action

- Cite a relevant quotation

- Predict a logical outcome

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion.

- Play the “So what” game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize. Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help her to apply your info and ideas to her own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications.

What NOT to do in a conclusion

- Do not repeat the exact wording of the thesis statement. The thesis statement should be restated in a new way.

- Do not introduce new points. Your conclusion should reinforce points you have already discussed in your essay.

- Do not end with an unnecessary announcement. Avoid phrases such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “to sum up.” The tone of your conclusion should signal that you are drawing to a close.

Your Turn

Consider your most recent writing assignment. Determine if you engaged your reader with an engaging hook. Did you have a thesis statement that discussed the overall point of your essay? Did you create topic sentences for each paragraph? Did your conclusion provide a sense of completeness about the essay’s topic?

Key Terms

- Arrangement

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- The hook

- Topic sentences

- Supporting sentences

- Conclusion

[h5p id=”10″]

[h5p id=”11″]

Reflective Response (Optional)

Review your arrangement for a writing assignment. What revisions in arrangement would you consider in your paper? Why?

Questions to Consider

When it comes to academic research, choosing a topic is often the hardest part of the process! In many instances, college instructors will provide guidelines or a broad topic for the assignment, but it’s your job to choose a narrower topic within those guidelines. Here are some questions to ask yourself before you decide on a topic to research:

- Have I been assigned a specific topic or can I choose my own?

- Is there a particular current event that interests me or an issue I feel strongly about? Can I select a topic that is closely related to my college major?

- Did the instructor specify what types of information sources I need to use?

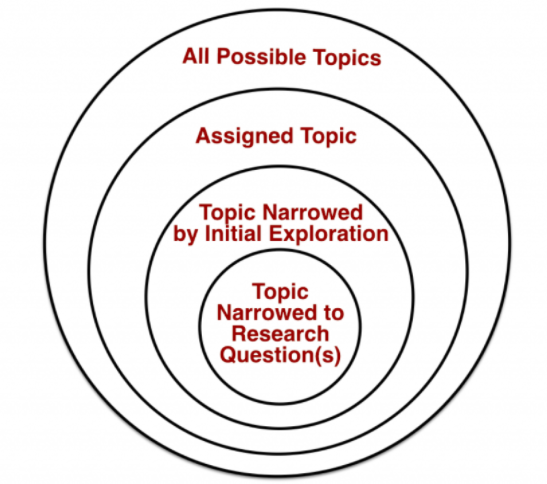

Narrowing Your Topic

It is important to select a topic that not only interests you or sparks your curiosity, but also one that is neither too broad or too narrow in scope. For example, if you are interested in climate change and wanted to choose that as a topic for your research paper, you would quickly find yourself overwhelmed with search results and information. You may find millions of search results about all different aspects of climate change, like policy, history, and the environment, and feel lost about where to begin.

An important step in the research process is narrowing down your larger topic into a smaller, more researchable topic. What is it about climate change that is most interesting to you? Is there something in particular that you've learned in class that relates to this topic that you could explore with your research? Watch the following video [3:10] to see how to recognize if your topic is too broad or too specific, and to learn some tips on what to do:

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

More Strategies

If you are having trouble selecting a topic or narrowing down your topic, here are some strategies that can help:

- Scan your course textbook for ideas

- Browse some magazines or newspapers for current events

- Dive into Wikipedia, or another encyclopedia, and see what sparks your interest

- Talk to your instructor, a librarian, or classmates, for ideas and guidance

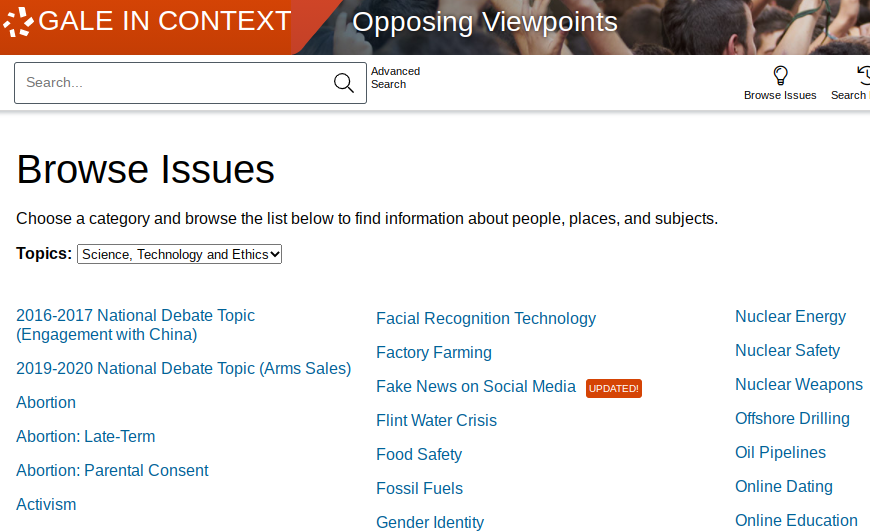

- Browse the "issues" and "topic" pages in library databases that include reference sources, like CQ Researcher or Opposing Viewpoints. These topic pages are similar to Wikipedia and give general background information on a topic and link to more specific information, which is helpful when narrowing down your topic. Some library databases have great features for getting your research started, like pro/con viewpoints, background information, timelines, and bibliographies for further reading. If you are unfamiliar with what library databases your college has a subscription to, ask a librarian for help!

Sources

Image: "Narrowing a Topic" by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under CC BY 4.0

"Picking Your Topic IS Research" by NC State University Libraries is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

Unlike 10-15 years ago when college students had to try to memorize citation formats and create each citation by hand, there are now many online tools available that will automatically create citations for many different types of information sources. Citation generators are tools that allow users to type, paste, or import certain information (like a source’s type, title, author, and date), and then create a citation in whatever format is needed (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

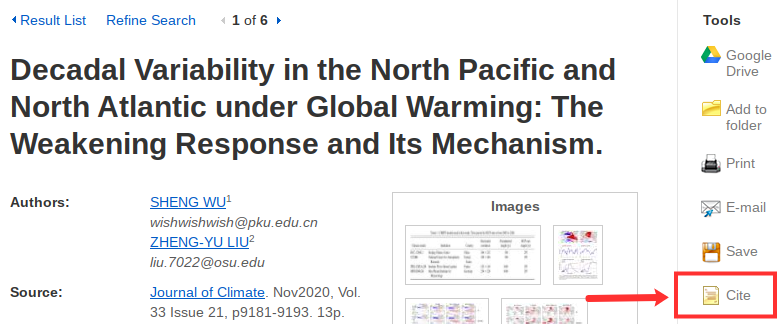

Library Databases

Almost all of your college library’s databases will have a convenient citation generator built right into them. In most cases, when you are reading an ebook, academic journal article, or another resource coming from a library database, there will be an icon somewhere on the page for a citation generator. These often offer a list of citation styles to choose from; they provide a citation for that particular source in whatever format is needed, so you can easily copy and paste the full citation into your assignment. The citation generator is not always located in the same spot, and does not always appear the same way in all library databases, but will often say “cite” or have quotation mark icons to indicate that it is a citation tool.

While these citation generators are incredibly helpful and convenient, they do sometimes make mistakes! Always be sure to double-check the citation generated for you—do not assume that all citations generated by a citation tool will be 100% correct.

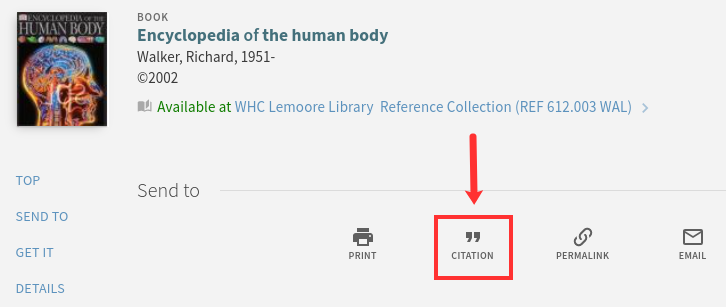

OneSearch

OneSearch also has its own convenient tool located within the record of every item record. The tool is located in the “Send to” section of the record and looks like one set of quotation marks with the word “CITATION” underneath. The citation style can be selected on the left-hand side (but please note, some colleges may list these formats differently from what is shown in the image below). Clicking on “COPY CITATION TO CLIPBOARD” will copy the citation so you can easily paste it into your bibliography (in Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or elsewhere). Besides checking the citation for accuracy, it is also important to check the formatting of your pasted text. Some formatting, like italics, may be lost when copying and pasting. Citation generators are fantastic tools that save a lot of time, but are not always 100% accurate!

Word Processors

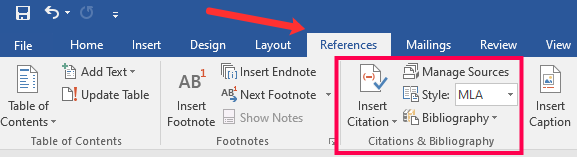

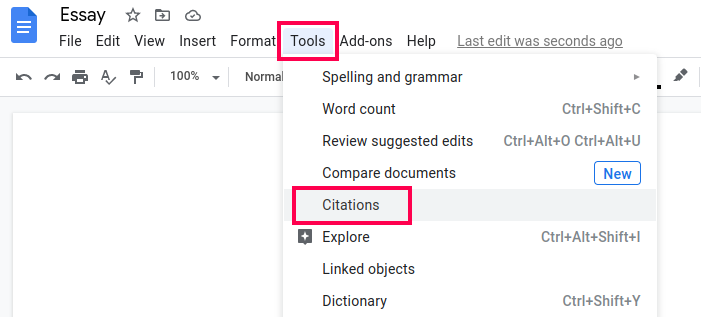

Two commonly used word processors—Microsoft Word and Google Docs—both have citation tools built into the software that make inserting in-text citations and compiling full citations quick and simple.

Microsoft Word’s citation generator is found under the toolbar section called “References,” and the “Insert Citation” tool allows users to plug in bibliographic information about each source used in their paper. The software will keep a running list of the sources, and allows for easy insertion of an in-text citation and a quick combination of citations into a bibliography in the appropriate citation style. An important thing to note is that Microsoft Word may not have the latest citation style format edition; for instance, it may only have the option to create citations in MLA 7th edition, but (as of the time this book was published) MLA 8th edition is the most up-to-date style.

The citation generator in Google Docs is located under the “Tools” menu item on the toolbar. Though this citation tool is much less robust than Microsoft Word’s, only having three citation styles to choose from, it still allows for quick insertion of both in-text citations and a bibliography at the end of the paper. As mentioned previously, the citation styles may not be the latest edition and it is important to always review any citation generated for you.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

How to distinguish among claims of fact, value and policy

In almost every college class, we are asked to read someone else’s writing, explain what that person is arguing, and point out the strengths and weaknesses of their argument. This section offers tools for figuring out the structure of an argument and describing it.

When you are trying to understand the basic ideas about something you have read, how do you go about it? An argument is a swarming cluster of words. How do you get to the heart of it?

In this section, we look at how to take notes not just on the meaning of each part of the argument but also on its relation to the other parts. Then we use these notes to draw a visual map of an argument. In the map, we see the argument's momentum as the reason points us toward the claim. We see how each element implies, supports, limits, or contradicts other elements. Thus, we begin to imagine where the argument is vulnerable and how it might be modified.

Types of Claims to Look For

As we make notes on what a writer is claiming at each point, it is worth distinguishing what kind of claim they are making.

Claims of Policy

The most familiar kind of argument demands action. It is easy to see when the writer is asking readers to do something. Here are a few phrases that signal a claim of policy, a claim that is pushing readers to do something:

- We should _____________.

- We must _____________.

- The solution is to _____________.

- The next step should be _____________.

- We should consider _____________.

- Further research should be done to determine _____________.

Here are a few sample claims of policy:

- Landlords should not be allowed to raise the rent more than 2% per year.

- The federal government should require a background check before allowing anyone to buy a gun.

- Social media accounts should not be censored in any way.

A claim of policy can also look like a direct command, such as, “If you are an American citizen, don’t let anything stop you from voting.”

Note that not all claims of policy give details or specifics about what should be done or how. Sometimes an author is only trying to build momentum and point us in a certain direction. For example, “Schools must find a way to make bathrooms more private for everyone, not just transgender people.”

Claims of policy don’t have to be about dramatic actions. Even discussion, research, and writing are kinds of action. For example, “Americans need to learn more about other wealthy nations’ health care systems in order to see how much better things could be in America.”

Claims of Fact

Arguments do not always point toward action. Sometimes writers want us to share their vision of reality on a particular subject. They may want to paint a picture of how something happened, describe a trend, or convince us that something is bad or good.

In some cases, the writer may want to share a particular vision of what something is like, what effects something has, how something is changing, or how something unfolded in the past. The argument might define a phenomenon, a trend, or a period of history.

Often these claims are simply presented as fact, and an uncritical reader may not see them as arguments at all. However, very often claims of fact are more controversial than they seem. For example, consider the claim “Caffeine boosts performance.” Does it really? How much? How do we know? Performance at what kind of task? For everyone? Doesn’t it also have downsides? A writer could spend a book convincing us that caffeine really boosts performance and explaining exactly what they mean by those three words.

Some phrases writers might use to introduce a claim of fact include the following:

- Research suggests that _____________.

- The data indicate that _____________.

- _____________causes _____________

- _____________leads to _____________.

Often a claim of fact will be the basis for other claims about what we should do that look more like what we associate with the word “argument.” However, many pieces of writing on websites and in magazines, office settings, and academic settings don’t try to move people toward action. They aim primarily at getting readers to agree with their view of what is fact. For example, it took many years of argument, research, and public messaging before most people accepted this claim: “Smoking causes cancer.”

Here are a few arguable sample claims of fact:

- It is easier to grow up biracial in Hawaii than in any other part of the United States.

- Raising the minimum wage will force many small businesses to lay off workers.

- Fires in the western United States have gotten worse primarily because of climate change.

- Antidepressants provide the most benefit when combined with talk therapy.

Claims of Value

In other cases, the writer is not just trying to convince us that something is a certain way or causes something, but is trying to say how good or bad that thing is. They are rating it, trying to get us to share her assessment of its value. Think of a movie or book review or an Amazon or Yelp review. Even a “like” on Facebook or a thumbs up on a text message is a claim of value.

Claims of value are fairly easy to identify. Some phrases that indicate a claim of value include the following:

- _____________is terrible/disappointing/underwhelming.

- _____________is mediocre/average/decent/acceptable.

- We should celebrate _____________.

- _____________is great, wonderful, fantastic, impressive, makes a substantial contribution to _____________.

A claim of value can also make a comparison. It might assert that something is better than, worse than, or equal to something else. Some phrases that signal a comparative claim of value include these:

- _____________is the best _____________.

- _____________is the worst _____________.

- _____________is better than _____________.

- _____________is worse than _____________.

The following are examples of claims of value:

- The Bay Area is the best place to start a biotech career.

- Forest fires are becoming the worst threat to public health in California.

- Human rights are more important than border security.

- Experimenting with drag is the best way I’ve found to explore my feelings about masculinity and femininity.

- It was so rude when that lady asked you what race you are.

Note that the above arguments all include claims of fact but go beyond observing to praise or criticize what they are observing.

Practice Exercise

On a social media site like Facebook or Twitter or on your favorite news site, find an example of one of each kind of claim.

Attributions: This section contains material from How Arguments Work—a Guide to Writing and Analyzing Texts in College by Anna Mills, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. It was edited and re-mixed by Dr. Tracey Watts and Dr. Dorie LaRue for the LOUIS OER Dual Enrollment course development program to create “English Composition II” and has been licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]()

In almost every college class, we are asked to read someone else’s writing, explain what that person is arguing, and point out the strengths and weaknesses of their argument. This section offers tools for figuring out the structure of an argument and describing it.

When you are trying to understand the basic ideas about something you have read, how do you go about it? An argument is a swarming cluster of words. How do you get to the heart of it?

In this section, we look at how to take notes not just on the meaning of each part of the argument but also on its relation to the other parts. Then we use these notes to draw a visual map of an argument. In the map, we see the argument's momentum as the reason points us toward the claim. We see how each element implies, supports, limits, or contradicts other elements. Thus, we begin to imagine where the argument is vulnerable and how it might be modified.

Types of Claims to Look For

As we make notes on what a writer is claiming at each point, it is worth distinguishing what kind of claim they are making.

Claims of Policy

The most familiar kind of argument demands action. It is easy to see when the writer is asking readers to do something. Here are a few phrases that signal a claim of policy, a claim that is pushing readers to do something:

- We should _____________.

- We must _____________.

- The solution is to _____________.

- The next step should be _____________.

- We should consider _____________.

- Further research should be done to determine _____________.

Here are a few sample claims of policy:

- Landlords should not be allowed to raise the rent more than 2% per year.

- The federal government should require a background check before allowing anyone to buy a gun.

- Social media accounts should not be censored in any way.

A claim of policy can also look like a direct command, such as, “If you are an American citizen, don’t let anything stop you from voting.”

Note that not all claims of policy give details or specifics about what should be done or how. Sometimes an author is only trying to build momentum and point us in a certain direction. For example, “Schools must find a way to make bathrooms more private for everyone, not just transgender people.”

Claims of policy don’t have to be about dramatic actions. Even discussion, research, and writing are kinds of action. For example, “Americans need to learn more about other wealthy nations’ health care systems in order to see how much better things could be in America.”

Claims of Fact

Arguments do not always point toward action. Sometimes writers want us to share their vision of reality on a particular subject. They may want to paint a picture of how something happened, describe a trend, or convince us that something is bad or good.

In some cases, the writer may want to share a particular vision of what something is like, what effects something has, how something is changing, or how something unfolded in the past. The argument might define a phenomenon, a trend, or a period of history.

Often these claims are simply presented as fact, and an uncritical reader may not see them as arguments at all. However, very often claims of fact are more controversial than they seem. For example, consider the claim “Caffeine boosts performance.” Does it really? How much? How do we know? Performance at what kind of task? For everyone? Doesn’t it also have downsides? A writer could spend a book convincing us that caffeine really boosts performance and explaining exactly what they mean by those three words.

Some phrases writers might use to introduce a claim of fact include the following:

- Research suggests that _____________.

- The data indicate that _____________.

- _____________causes _____________

- _____________leads to _____________.

Often a claim of fact will be the basis for other claims about what we should do that look more like what we associate with the word “argument.” However, many pieces of writing on websites and in magazines, office settings, and academic settings don’t try to move people toward action. They aim primarily at getting readers to agree with their view of what is fact. For example, it took many years of argument, research, and public messaging before most people accepted this claim: “Smoking causes cancer.”

Here are a few arguable sample claims of fact:

- It is easier to grow up biracial in Hawaii than in any other part of the United States.

- Raising the minimum wage will force many small businesses to lay off workers.

- Fires in the western United States have gotten worse primarily because of climate change.

- Antidepressants provide the most benefit when combined with talk therapy.

Claims of Value

In other cases, the writer is not just trying to convince us that something is a certain way or causes something, but is trying to say how good or bad that thing is. They are rating it, trying to get us to share her assessment of its value. Think of a movie or book review or an Amazon or Yelp review. Even a “like” on Facebook or a thumbs up on a text message is a claim of value.

Claims of value are fairly easy to identify. Some phrases that indicate a claim of value include the following:

- _____________is terrible/disappointing/underwhelming.

- _____________is mediocre/average/decent/acceptable.

- We should celebrate _____________.

- _____________is great, wonderful, fantastic, impressive, makes a substantial contribution to _____________.

A claim of value can also make a comparison. It might assert that something is better than, worse than, or equal to something else. Some phrases that signal a comparative claim of value include these:

- _____________is the best _____________.

- _____________is the worst _____________.

- _____________is better than _____________.

- _____________is worse than _____________.

The following are examples of claims of value:

- The Bay Area is the best place to start a biotech career.

- Forest fires are becoming the worst threat to public health in California.

- Human rights are more important than border security.

- Experimenting with drag is the best way I’ve found to explore my feelings about masculinity and femininity.

- It was so rude when that lady asked you what race you are.

Note that the above arguments all include claims of fact but go beyond observing to praise or criticize what they are observing.

Practice Exercise

On a social media site like Facebook or Twitter or on your favorite news site, find an example of one of each kind of claim.

Attributions: This section contains material from How Arguments Work—a Guide to Writing and Analyzing Texts in College by Anna Mills, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. It was edited and re-mixed by Dr. Tracey Watts and Dr. Dorie LaRue for the LOUIS OER Dual Enrollment course development program to create “English Composition II” and has been licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]()