Sound and Valid Argument

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Includes glossary of terms including: validity, deductive and inductive reasoning

Academic Speak – Clarification

When reading about academic writing you will sometimes come across a set of words that seem to be used somewhat interchangeably and even randomly at times. So, just to set the record straight:

Claim / assertion / premise / proposition are all statements that require support either to justify them or prove their soundness. They need further evidence. These are the starting point of reasoning.

Position / Thesis identify the stance you are taking on the main topic of the essay and it is generated by the essay question provided by your instructor. In an analytical or critical essay, it may indicate more than one available stance.

Also, some authors refer to the thesis as the premise or proposition. This is not the best description, though it is not completely inaccurate because the thesis statement does need to be supported with sound evidence and valid arguments throughout the essay.

Glossary of Terms

Argument – noun

- Logic – a reason or set of reasons given in support of an idea, action, or theory

Claim – noun (synonyms – premise, assertion, proposition)

- an assertion that something is true

Claim – verb

- state or assert something, typically without providing evidence or proof

Counter claim – noun

- a claim made to rebut a previous claim; refutation of opposing arguments

Deduction – noun

- Logic – the act of understanding something, or drawing to a conclusion, based on evidence

Induction – noun

- the process or action of bringing about or giving rise to something

Position – noun (synonym – thesis)

- the main point or overall argument that is to be proven or justified. It focuses the writer’s ideas and minor arguments

Premise – noun (synonyms – claim, assertion, proposition)

- Logic – a previous statement or proposition from which another is inferred or follows as a conclusion

- a statement in an argument that provides reason or support for the conclusion

Proposition – noun (synonyms – premise, claim, assertion)

- Logic – a statement or assertion that expresses a judgment or opinion

- a statement that expresses a concept that can be true or false

Soundness – noun

- the quality of being based on valid reason or good judgment

- the soundness of an argument has two qualities 1. valid structure 2. true premises

Validity – noun

- Logic – the quality of being justifiable by reason

- the conclusion follows from the premises

Introduction to Academic Argument

The capacity to academically argue is a core skill that many students are not taught adequately prior to university writing. Argumentative ability is centered around knowledge. Not only knowledge of a topic, but knowledge of how to write a clear and coherent argument. Basically, an argument is an informed position, on a topic, that you are supporting or defending with sound evidence and valid conclusions. An essay may have one overall argument or position, yet include a series or set of smaller arguments that support or develop the overall position of the writer. This may include evaluating sources or contradictory evidence. The position is stated in the thesis (see Chapter 21 & 26). This position must be supported by sound academic evidence obtained through reading and research.

Suspend Bias

In order to develop sound and valid arguments, students must first suspend their personal judgments or bias on a topic (see Chapter 30). This can be achieved through self-reflection and critical thinking. Academic writing must be clear and objective, and this means you must be open and willing to examine more than one perspective of a topic or argument without preconceived ideas and opinions, without bias. Make a conscious effort to step beyond your own subjectivity and depersonalize both the topic and the supporting evidence. Through critical thinking skills, such as objectivity and analysis, you can begin to closely examine and evaluate sources and the production of knowledge. As a writer, sound and valid reasoning assists you in determining the best evidence to support your own claims and in evaluating the claims of other writers. As an objective writer, you should remain open to other viewpoints, though rely on your critical analysis skills to both identify and write sound and valid academic arguments.

Validity

Validity primarily means that in an argument the conclusion follows from the premises. If the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Salva veritate (Latin) means “without loss of truth” – a rule of inference must be truth preserving; it must take one from truths to truths = Validity [1]

Examples:

Valid Argument

- All cats are aliens

- Felix is a cat

Therefore, Felix is an alien

This is a valid argument. Hypothetically, if all the premises are true, then the conclusion cannot be false. It is logically impossible for the premises to be true and for the conclusion to be false.

Invalid Argument

- All cats are aliens

- Felix is an alien

Therefore, Felix is a cat

This is an invalid argument. Hypothetically, just because Felix is an alien does not guarantee that he is a cat. There may be other types of creatures that are also aliens. However, if the first premise said “Only cats are aliens”, then the argument would be valid.

- Only cats are aliens

- Felix is an alien

Therefore, Felix is a cat

This is a valid argument. No individual premise (claim, assertion) is labelled as valid or invalid, only the argument structure as a whole. However, premises can be checked for soundness.

Soundness

The soundness of an argument relies on two qualities:

1. the structure of the argument is valid (see above)

2. the premises are true and therefore the conclusion is also true.

Hence, Felix is not an alien unless we can provide sound proof (truth or true facts) that support this premise (claim, assertion). We would also need to provide evidence that Felix is indeed a cat! So, while the argument structure may be correct (valid), the premises could be untrue, therefore the premises and overall argument lacks soundness.

Deductive Syllogism

The structure of the above arguments is called a deductive syllogism and it is the the conventional way of displaying or writing a deductive argument:

Premise + Premise = Conclusion

Of course, you can have more than two premises or reasons to support your conclusion. In academic writing the major position is put forward in the thesis statement and the balance of the essay has the task of unpacking the claims and counter-claims surrounding the key arguments and providing supporting evidence. Note also, you should never begin your assignment preparation with a predetermined conclusion in mind (called “jumping to the conclusion”) and work your argument back from that point. Yes, in an essay the thesis is proposed in the introduction, though it is assumed that you arrived at this thesis statement through research and careful consideration of the facts and evidence surrounding the chosen topic. Whereas “jumping to the conclusion” beforehand and attempting to make the evidence fit your thesis is not the actions of an open and critical thinker who responds to evidence found through research. It instead indicates a very determined bias in thinking and academic writing.

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is often defined as the inference from particular to general[2]. It is based on formulating theories through detailed observations. It is useful in scientific fields, however, it presupposes that the future will resemble the past. This type of reasoning moves from evidence to assumptions (about the future) to a claim. The claim cannot be a deductive conclusion, only a generalization from observable evidence and applied assumptions.

Example

You’re in the supermarket and would like to buy a couple of ripe avocados. To determine if they are ripe, you give them a gentle squeeze. After testing three to four from the fruit case, you determine that they are all still too green and decide not to purchase avocados.

Through induction, you have made your own observation, and from the evidence at hand made an assumption – they’re all too green. This is a generalization made using observable evidence and applying an assumption. As you cannot know for certain that every avocado is green, without testing each one, this cannot be a deductive argument. While there may be sufficient evidence to make a decision and therefore, strong inductive reasoning, the reasoning has not been proven true, merely an assumption.

While inductive reasoning may be useful in formulating a scientific hypothesis for further testing, it is not a strong form of reasoning for academic writing.

Final Note

Good academic writing is founded on your capacity to academically argue from a well-researched and informed perspective, free from subjectivity and personal bias. The deductive syllogism is a good illustration of sound and valid argument structure that is the backbone of all well-written academic discussions.

Video

Watch the video below for further information and examples of deductive and inductive reasoning. Particularly helpful is the middle section on evaluating deductive and inductive arguments / reasoning.

Test your knowledge with five quick questions:

[h5p id=”28″]

- Honderich, T. (Ed.). (2005). The Oxford companion to philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ↵

- Honderich, T. (Ed.). (2005). The Oxford companion to philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ↵

- Plumlee, D., & Taverna, J. [Center for Innovation in Legal Education]. (2013, August 24). Episode 1.3: Deductive and inductive arguments. ↵

Adapted by Liz Delf, Rob Drummond, and Kristy Kelly

Moving beyond the Five-Paragraph Theme

As an instructor, I’ve noted that a number of new (and sometimes not-so-new) students are skilled wordsmiths and generally clear thinkers but are nevertheless stuck in a high school style of writing. They struggle to let go of certain assumptions about how an academic paper should be. Some students who have mastered that form, and enjoyed a lot of success from doing so, assume that college writing is simply more of the same. The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay—often called the five-paragraph theme—are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clearfl and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion.

In college you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph theme, as such, is bland and formulaic; it doesn’t compel deep thinking. Your instructors are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically structured paper.

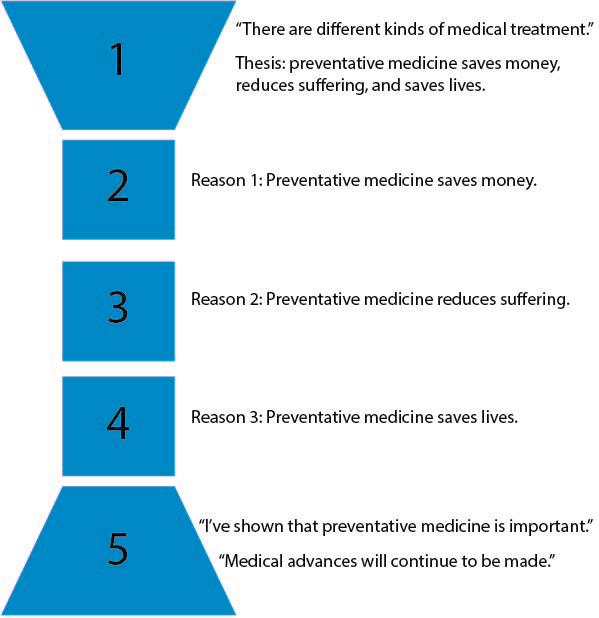

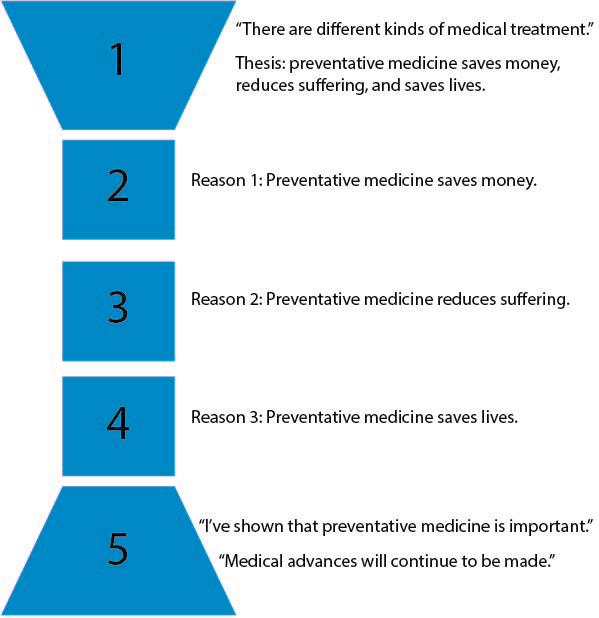

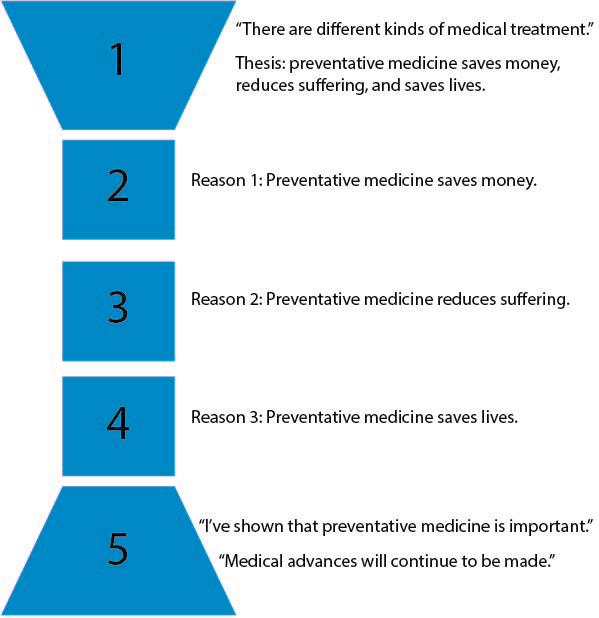

Figures 12.1 and 12.2 contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper. The five-paragraph theme (outlined in figure 12.1) is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

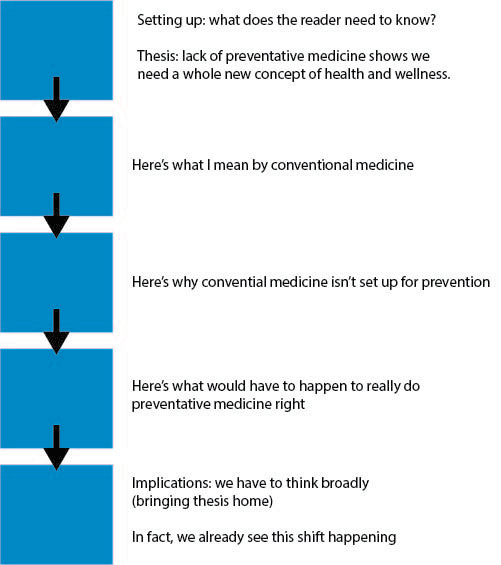

In contrast, figure 12.2 represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme (figure 12.1), it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (figure 12.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, nonobvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in figure 12.1 was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. (And it is worth noting that there are limited moments in college where the five-paragraph structure is still useful—in-class essay exams, for example.) But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your instructors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

The Three-Story Thesis

From the Ground Up

You have no doubt been drilled on the need for a thesis statement and its proper location at the end of the introduction. And you also know that all of the key points of the paper should clearly support the central driving thesis. Indeed, the whole model of the five-paragraph theme hinges on a clearly stated and consistent thesis. However, some students are surprised—and dismayed—when some of their early college papers are criticized for not having a good thesis. Their instructor might even claim that the paper doesn’t have a thesis when, in the author’s view, it clearly does. So what makes a good thesis in college?

- A good thesis is nonobvious

- High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “Sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable

- In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the nonobvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs three, five, ten, or twenty pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “Sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “Sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified

- Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a clearly stated and specific thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis. There is no such thing as spoilers in an academic paper.

- A good thesis includes implications.

- Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well-supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency. That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well-specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

- Version A: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade.

- Version B: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade. The economic role of linen raises important questions about how shifting environmental conditions can influence economic relationships and, by extension, political conflicts.

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your instructors, who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning. Ask yourself, So what? Why does this issue or argument matter? Why is it important? Addressing these questions will go a long way toward making your paper more complex and engaging.

How do you produce a good, strong thesis? And how do you know when you’ve gotten there? Many instructors and writers embrace a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809–1894). He compares a good thesis to a three-story building:

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight. (50)

In other words,

- One-story theses state inarguable facts. What’s the background?

- Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. What is your argument?

- Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications. Why does it matter?

Thesis: that’s the word that pops at me whenever I write an essay. Seeing this word in the prompt scared me and made me think to myself, “Oh great, what are they really looking for?” or “How am I going to make a thesis for a college paper?” When rehearing that I would be focusing on theses again in a class, I said to myself, “Here we go again!” But after learning about the three-story thesis, I never had a problem with writing another thesis. In fact, I look forward to being asked on a paper to create a thesis.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story or level, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

The concept of a three-story thesis framework was the most helpful piece of information I gained from the writing component of DCC 100. The first time I utilized it in a college paper, my professor included “good thesis” and “excellent introduction” in her notes and graded it significantly higher than my previous papers. You can expect similar results if you dig deeper to form three-story theses. More importantly, doing so will make the actual writing of your paper more straightforward as well. Arguing something specific makes the structure of your paper much easier to design.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings on its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well-considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not.

In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together. Here is an example:

- First story (facts only)

- Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story (arguable point)

- While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of as an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story (larger implications)

- Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

The final thesis would be all three of these pieces together. These stories build on one another; they don’t replace the previous story.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis:

- First story

- Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story

- However, in her work, we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story

- Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story

- Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the US of the light brown apple moth (LBAM), an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story

- Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several Southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story

- Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well-informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Three-Story Theses and the Organically Structured Argument

The three-story thesis is a beautiful thing. For one, it gives a paper authentic momentum. The first paragraph doesn’t just start with some broad, vague statement; every sentence is crucial for setting up the thesis. The body paragraphs build on one another, moving through each step of the logical chain. Each paragraph leads inevitably to the next, making the transitions from paragraph to paragraph feel wholly natural. The conclusion, instead of being a mirror-image paraphrase of the introduction, builds out the third story by explaining the broader implications of the argument. It offers new insight without departing from the flow of the analysis.

I should note here that a paper with this kind of momentum often reads like it was knocked out in one inspired sitting. But in reality, just like accomplished athletes, artists, and musicians, masterful writers make the difficult thing look easy. As writer Anne Lamott notes, reading a well-written piece feels like its author sat down and typed it out, “bounding along like huskies across the snow.” However, she continues,

This is just the fantasy of the uninitiated. I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. (21)

Experienced writers don’t figure out what they want to say and then write it. They write in order to figure out what they want to say.

Experienced writers develop theses in dialogue with the body of the essay. An initial characterization of the problem leads to a tentative thesis, and then drafting the body of the paper reveals thorny contradictions or critical areas of ambiguity, prompting the writer to revisit or expand the body of evidence and then refine the thesis based on that fresh look. The revised thesis may require that body paragraphs be reordered and reshaped to fit the emerging three-story thesis. Throughout the process, the thesis serves as an anchor point while the author wades through the morass of facts and ideas. The dialogue between thesis and body continues until the author is satisfied or the due date arrives, whatever comes first. It’s an effortful and sometimes tedious process.

Novice writers, in contrast, usually oversimplify the writing process. They formulate some first-impression thesis, produce a reasonably organized outline, and then flesh it out with text, never taking the time to reflect or truly revise their work. They assume that revision is a step backward when, in reality, it is a major step forward.

Everyone has a different way that they like to write. For instance, I like to pop my earbuds in, blast dubstep music, and write on a whiteboard. I like using the whiteboard because it is a lot easier to revise and edit while you write. After I finish writing a paragraph that I am completely satisfied with on the whiteboard, I sit in front of it with my laptop and just type it up.

Another benefit of the three-story thesis framework is that it demystifies what a “strong” argument is in academic culture. In an era of political polarization, many students may think that a strong argument is based on a simple, bold, combative statement that is promoted in the most forceful way possible. “Gun control is a travesty!” “Shakespeare is the best writer who ever lived!” When students are encouraged to consider contrasting perspectives in their papers, they fear that doing so will make their own thesis seem mushy and weak.

However, in academics a “strong” argument is comprehensive and nuanced, not simple and polemical. The purpose of the argument is to explain to readers why the author—through the course of his or her in-depth study—has arrived at a somewhat surprising point. On that basis, it has to consider plausible counterarguments and contradictory information. Academic argumentation exemplifies the popular adage about all writing: show, don’t tell. In crafting and carrying out the three-story thesis, you are showing your reader the work you have done.

The model of the organically structured paper and the three-story thesis framework explained here is the very foundation of the paper itself and the process that produces it. Your instructors assume that you have the self-motivation and organizational skills to pursue your analysis with both rigor and flexibility; that is, they envision you developing, testing, refining, and sometimes discarding your own ideas based on a clear-eyed and open-minded assessment of the evidence before you.

The original chapter, Constructing the Thesis and Argument—from the Ground Up by Amy Guptill, is from Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence

Discussion Questions

- What writing “rules” were you taught in the past? This might be about essay structure, style, or something else. Which of these rules seem to be true in college writing? Which ones are not true in college?

- In what contexts is the five-paragraph essay a useful structure? Why is it not helpful in other contexts—what’s the problem?

Activities

- Put the following “stories” of a thesis in order to make a strong thesis statement:

- Despite their appeal to patients, robotic pets should not be used widely, since they cause more problems than they solve.

- In recent years, robotic pets have been used in medical settings to help children and elderly patients feel emotionally supported and loved.

- Shifting affection to robotic pets rather than live animals suggests a major change in empathy and humanity and could have long-term costs that have not been fully considered.

- Here is a list of one-story theses. Come up with three-story versions of each one.

- Television programming includes content that some find objectionable.

- The percentage of children and youth who are overweight or obese has risen in recent decades.

- First-year college students must learn how to independently manage their time.

- The things we surround ourselves with symbolize who we are.

- Find a scholarly article or book that is interesting to you. Focusing on the abstract and introduction, outline the first, second, and third stories of its thesis.

- Find an example of a five-paragraph theme (online essay mills, your own high school work), produce an alternative three-story thesis, and outline an organically structured paper to carry that thesis out.

Additional Resources

- The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers an excellent, readable rundown on the five-paragraph theme, why most college writing assignments want you to go beyond it, and those times when the simpler structure is actually a better choice.

- There are many useful websites that describe good thesis statements and provide examples. Those from the writing centers at Hamilton College and Purdue University are especially helpful.

Works Cited

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. The Poet at the Breakfast-Table: His Talks with His Fellow-Boarders and the Reader. James R. Osgood, 1872.

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. Pantheon, 1994.

Adapted by Liz Delf, Rob Drummond, and Kristy Kelly

Moving beyond the Five-Paragraph Theme

As an instructor, I’ve noted that a number of new (and sometimes not-so-new) students are skilled wordsmiths and generally clear thinkers but are nevertheless stuck in a high school style of writing. They struggle to let go of certain assumptions about how an academic paper should be. Some students who have mastered that form, and enjoyed a lot of success from doing so, assume that college writing is simply more of the same. The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay—often called the five-paragraph theme—are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clearfl and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion.

In college you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph theme, as such, is bland and formulaic; it doesn’t compel deep thinking. Your instructors are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically structured paper.

Figures 12.1 and 12.2 contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper. The five-paragraph theme (outlined in figure 12.1) is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

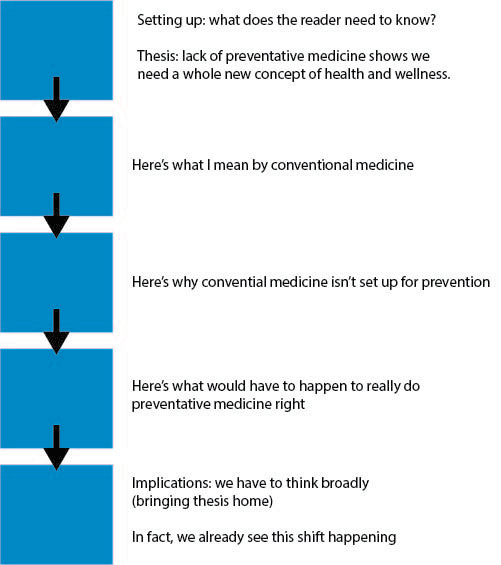

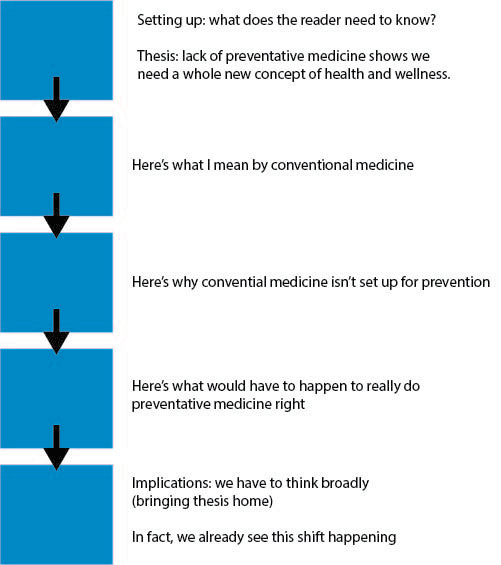

In contrast, figure 12.2 represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme (figure 12.1), it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (figure 12.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, nonobvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in figure 12.1 was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. (And it is worth noting that there are limited moments in college where the five-paragraph structure is still useful—in-class essay exams, for example.) But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your instructors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

The Three-Story Thesis

From the Ground Up

You have no doubt been drilled on the need for a thesis statement and its proper location at the end of the introduction. And you also know that all of the key points of the paper should clearly support the central driving thesis. Indeed, the whole model of the five-paragraph theme hinges on a clearly stated and consistent thesis. However, some students are surprised—and dismayed—when some of their early college papers are criticized for not having a good thesis. Their instructor might even claim that the paper doesn’t have a thesis when, in the author’s view, it clearly does. So what makes a good thesis in college?

- A good thesis is nonobvious

- High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “Sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable

- In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the nonobvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs three, five, ten, or twenty pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “Sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “Sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified

- Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a clearly stated and specific thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis. There is no such thing as spoilers in an academic paper.

- A good thesis includes implications.

- Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well-supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency. That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well-specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

- Version A: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade.

- Version B: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade. The economic role of linen raises important questions about how shifting environmental conditions can influence economic relationships and, by extension, political conflicts.

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your instructors, who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning. Ask yourself, So what? Why does this issue or argument matter? Why is it important? Addressing these questions will go a long way toward making your paper more complex and engaging.

How do you produce a good, strong thesis? And how do you know when you’ve gotten there? Many instructors and writers embrace a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809–1894). He compares a good thesis to a three-story building:

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight. (50)

In other words,

- One-story theses state inarguable facts. What’s the background?

- Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. What is your argument?

- Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications. Why does it matter?

Thesis: that’s the word that pops at me whenever I write an essay. Seeing this word in the prompt scared me and made me think to myself, “Oh great, what are they really looking for?” or “How am I going to make a thesis for a college paper?” When rehearing that I would be focusing on theses again in a class, I said to myself, “Here we go again!” But after learning about the three-story thesis, I never had a problem with writing another thesis. In fact, I look forward to being asked on a paper to create a thesis.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story or level, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

The concept of a three-story thesis framework was the most helpful piece of information I gained from the writing component of DCC 100. The first time I utilized it in a college paper, my professor included “good thesis” and “excellent introduction” in her notes and graded it significantly higher than my previous papers. You can expect similar results if you dig deeper to form three-story theses. More importantly, doing so will make the actual writing of your paper more straightforward as well. Arguing something specific makes the structure of your paper much easier to design.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings on its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well-considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not.

In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together. Here is an example:

- First story (facts only)

- Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story (arguable point)

- While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of as an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story (larger implications)

- Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

The final thesis would be all three of these pieces together. These stories build on one another; they don’t replace the previous story.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis:

- First story

- Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story

- However, in her work, we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story

- Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story

- Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the US of the light brown apple moth (LBAM), an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story

- Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several Southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story

- Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well-informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Three-Story Theses and the Organically Structured Argument

The three-story thesis is a beautiful thing. For one, it gives a paper authentic momentum. The first paragraph doesn’t just start with some broad, vague statement; every sentence is crucial for setting up the thesis. The body paragraphs build on one another, moving through each step of the logical chain. Each paragraph leads inevitably to the next, making the transitions from paragraph to paragraph feel wholly natural. The conclusion, instead of being a mirror-image paraphrase of the introduction, builds out the third story by explaining the broader implications of the argument. It offers new insight without departing from the flow of the analysis.

I should note here that a paper with this kind of momentum often reads like it was knocked out in one inspired sitting. But in reality, just like accomplished athletes, artists, and musicians, masterful writers make the difficult thing look easy. As writer Anne Lamott notes, reading a well-written piece feels like its author sat down and typed it out, “bounding along like huskies across the snow.” However, she continues,

This is just the fantasy of the uninitiated. I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. (21)

Experienced writers don’t figure out what they want to say and then write it. They write in order to figure out what they want to say.

Experienced writers develop theses in dialogue with the body of the essay. An initial characterization of the problem leads to a tentative thesis, and then drafting the body of the paper reveals thorny contradictions or critical areas of ambiguity, prompting the writer to revisit or expand the body of evidence and then refine the thesis based on that fresh look. The revised thesis may require that body paragraphs be reordered and reshaped to fit the emerging three-story thesis. Throughout the process, the thesis serves as an anchor point while the author wades through the morass of facts and ideas. The dialogue between thesis and body continues until the author is satisfied or the due date arrives, whatever comes first. It’s an effortful and sometimes tedious process.

Novice writers, in contrast, usually oversimplify the writing process. They formulate some first-impression thesis, produce a reasonably organized outline, and then flesh it out with text, never taking the time to reflect or truly revise their work. They assume that revision is a step backward when, in reality, it is a major step forward.

Everyone has a different way that they like to write. For instance, I like to pop my earbuds in, blast dubstep music, and write on a whiteboard. I like using the whiteboard because it is a lot easier to revise and edit while you write. After I finish writing a paragraph that I am completely satisfied with on the whiteboard, I sit in front of it with my laptop and just type it up.

Another benefit of the three-story thesis framework is that it demystifies what a “strong” argument is in academic culture. In an era of political polarization, many students may think that a strong argument is based on a simple, bold, combative statement that is promoted in the most forceful way possible. “Gun control is a travesty!” “Shakespeare is the best writer who ever lived!” When students are encouraged to consider contrasting perspectives in their papers, they fear that doing so will make their own thesis seem mushy and weak.

However, in academics a “strong” argument is comprehensive and nuanced, not simple and polemical. The purpose of the argument is to explain to readers why the author—through the course of his or her in-depth study—has arrived at a somewhat surprising point. On that basis, it has to consider plausible counterarguments and contradictory information. Academic argumentation exemplifies the popular adage about all writing: show, don’t tell. In crafting and carrying out the three-story thesis, you are showing your reader the work you have done.

The model of the organically structured paper and the three-story thesis framework explained here is the very foundation of the paper itself and the process that produces it. Your instructors assume that you have the self-motivation and organizational skills to pursue your analysis with both rigor and flexibility; that is, they envision you developing, testing, refining, and sometimes discarding your own ideas based on a clear-eyed and open-minded assessment of the evidence before you.

The original chapter, Constructing the Thesis and Argument—from the Ground Up by Amy Guptill, is from Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence

Discussion Questions

- What writing “rules” were you taught in the past? This might be about essay structure, style, or something else. Which of these rules seem to be true in college writing? Which ones are not true in college?

- In what contexts is the five-paragraph essay a useful structure? Why is it not helpful in other contexts—what’s the problem?

Activities

- Put the following “stories” of a thesis in order to make a strong thesis statement:

- Despite their appeal to patients, robotic pets should not be used widely, since they cause more problems than they solve.

- In recent years, robotic pets have been used in medical settings to help children and elderly patients feel emotionally supported and loved.

- Shifting affection to robotic pets rather than live animals suggests a major change in empathy and humanity and could have long-term costs that have not been fully considered.

- Here is a list of one-story theses. Come up with three-story versions of each one.

- Television programming includes content that some find objectionable.

- The percentage of children and youth who are overweight or obese has risen in recent decades.

- First-year college students must learn how to independently manage their time.

- The things we surround ourselves with symbolize who we are.

- Find a scholarly article or book that is interesting to you. Focusing on the abstract and introduction, outline the first, second, and third stories of its thesis.

- Find an example of a five-paragraph theme (online essay mills, your own high school work), produce an alternative three-story thesis, and outline an organically structured paper to carry that thesis out.

Additional Resources

- The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers an excellent, readable rundown on the five-paragraph theme, why most college writing assignments want you to go beyond it, and those times when the simpler structure is actually a better choice.

- There are many useful websites that describe good thesis statements and provide examples. Those from the writing centers at Hamilton College and Purdue University are especially helpful.

Works Cited

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. The Poet at the Breakfast-Table: His Talks with His Fellow-Boarders and the Reader. James R. Osgood, 1872.

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. Pantheon, 1994.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Moving beyond the 5-paragraph theme to a more organic essay

As an instructor, I’ve noted that a number of new (and sometimes not-so-new) students are skilled wordsmiths and generally clear thinkers but are nevertheless stuck in a high school style of writing. They struggle to let go of certain assumptions about how an academic paper should be. Some students who have mastered that form, and enjoyed a lot of success from doing so, assume that college writing is simply more of the same. The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay—often called the five-paragraph theme—are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clearfl and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion.

In college you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph theme, as such, is bland and formulaic; it doesn’t compel deep thinking. Your instructors are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically structured paper.

Figures 12.1 and 12.2 contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper. The five-paragraph theme (outlined in figure 12.1) is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

In contrast, figure 12.2 represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme (figure 12.1), it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (figure 12.2), each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, nonobvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking, “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in figure 12.1 was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. (And it is worth noting that there are limited moments in college where the five-paragraph structure is still useful—in-class essay exams, for example.) But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your instructors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

The Three-Story Thesis

From the Ground Up

You have no doubt been drilled on the need for a thesis statement and its proper location at the end of the introduction. And you also know that all of the key points of the paper should clearly support the central driving thesis. Indeed, the whole model of the five-paragraph theme hinges on a clearly stated and consistent thesis. However, some students are surprised—and dismayed—when some of their early college papers are criticized for not having a good thesis. Their instructor might even claim that the paper doesn’t have a thesis when, in the author’s view, it clearly does. So what makes a good thesis in college?

- A good thesis is nonobvious

- High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “Sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable

- In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the nonobvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs three, five, ten, or twenty pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “Sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “Sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified

- Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a clearly stated and specific thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis. There is no such thing as spoilers in an academic paper.

- A good thesis includes implications.

- Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well-supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency. That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well-specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

- Version A: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade.

- Version B: Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade. The economic role of linen raises important questions about how shifting environmental conditions can influence economic relationships and, by extension, political conflicts.

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your instructors, who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning. Ask yourself, So what? Why does this issue or argument matter? Why is it important? Addressing these questions will go a long way toward making your paper more complex and engaging.

How do you produce a good, strong thesis? And how do you know when you’ve gotten there? Many instructors and writers embrace a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809–1894). He compares a good thesis to a three-story building:

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight. (50)

In other words,

- One-story theses state inarguable facts. What’s the background?

- Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. What is your argument?

- Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications. Why does it matter?

Thesis: that’s the word that pops at me whenever I write an essay. Seeing this word in the prompt scared me and made me think to myself, “Oh great, what are they really looking for?” or “How am I going to make a thesis for a college paper?” When rehearing that I would be focusing on theses again in a class, I said to myself, “Here we go again!” But after learning about the three-story thesis, I never had a problem with writing another thesis. In fact, I look forward to being asked on a paper to create a thesis.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story or level, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

The concept of a three-story thesis framework was the most helpful piece of information I gained from the writing component of DCC 100. The first time I utilized it in a college paper, my professor included “good thesis” and “excellent introduction” in her notes and graded it significantly higher than my previous papers. You can expect similar results if you dig deeper to form three-story theses. More importantly, doing so will make the actual writing of your paper more straightforward as well. Arguing something specific makes the structure of your paper much easier to design.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings on its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well-considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not.

In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together. Here is an example:

- First story (facts only)

- Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story (arguable point)

- While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of as an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story (larger implications)

- Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

The final thesis would be all three of these pieces together. These stories build on one another; they don’t replace the previous story.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis:

- First story

- Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story

- However, in her work, we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story

- Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story

- Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the US of the light brown apple moth (LBAM), an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story

- Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several Southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story

- Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well-informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Three-Story Theses and the Organically Structured Argument

The three-story thesis is a beautiful thing. For one, it gives a paper authentic momentum. The first paragraph doesn’t just start with some broad, vague statement; every sentence is crucial for setting up the thesis. The body paragraphs build on one another, moving through each step of the logical chain. Each paragraph leads inevitably to the next, making the transitions from paragraph to paragraph feel wholly natural. The conclusion, instead of being a mirror-image paraphrase of the introduction, builds out the third story by explaining the broader implications of the argument. It offers new insight without departing from the flow of the analysis.

I should note here that a paper with this kind of momentum often reads like it was knocked out in one inspired sitting. But in reality, just like accomplished athletes, artists, and musicians, masterful writers make the difficult thing look easy. As writer Anne Lamott notes, reading a well-written piece feels like its author sat down and typed it out, “bounding along like huskies across the snow.” However, she continues,

This is just the fantasy of the uninitiated. I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. (21)

Experienced writers don’t figure out what they want to say and then write it. They write in order to figure out what they want to say.

Experienced writers develop theses in dialogue with the body of the essay. An initial characterization of the problem leads to a tentative thesis, and then drafting the body of the paper reveals thorny contradictions or critical areas of ambiguity, prompting the writer to revisit or expand the body of evidence and then refine the thesis based on that fresh look. The revised thesis may require that body paragraphs be reordered and reshaped to fit the emerging three-story thesis. Throughout the process, the thesis serves as an anchor point while the author wades through the morass of facts and ideas. The dialogue between thesis and body continues until the author is satisfied or the due date arrives, whatever comes first. It’s an effortful and sometimes tedious process.

Novice writers, in contrast, usually oversimplify the writing process. They formulate some first-impression thesis, produce a reasonably organized outline, and then flesh it out with text, never taking the time to reflect or truly revise their work. They assume that revision is a step backward when, in reality, it is a major step forward.

Everyone has a different way that they like to write. For instance, I like to pop my earbuds in, blast dubstep music, and write on a whiteboard. I like using the whiteboard because it is a lot easier to revise and edit while you write. After I finish writing a paragraph that I am completely satisfied with on the whiteboard, I sit in front of it with my laptop and just type it up.

Another benefit of the three-story thesis framework is that it demystifies what a “strong” argument is in academic culture. In an era of political polarization, many students may think that a strong argument is based on a simple, bold, combative statement that is promoted in the most forceful way possible. “Gun control is a travesty!” “Shakespeare is the best writer who ever lived!” When students are encouraged to consider contrasting perspectives in their papers, they fear that doing so will make their own thesis seem mushy and weak.

However, in academics a “strong” argument is comprehensive and nuanced, not simple and polemical. The purpose of the argument is to explain to readers why the author—through the course of his or her in-depth study—has arrived at a somewhat surprising point. On that basis, it has to consider plausible counterarguments and contradictory information. Academic argumentation exemplifies the popular adage about all writing: show, don’t tell. In crafting and carrying out the three-story thesis, you are showing your reader the work you have done.

The model of the organically structured paper and the three-story thesis framework explained here is the very foundation of the paper itself and the process that produces it. Your instructors assume that you have the self-motivation and organizational skills to pursue your analysis with both rigor and flexibility; that is, they envision you developing, testing, refining, and sometimes discarding your own ideas based on a clear-eyed and open-minded assessment of the evidence before you.

The original chapter, Constructing the Thesis and Argument—from the Ground Up by Amy Guptill, is from Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence

Discussion Questions

- What writing “rules” were you taught in the past? This might be about essay structure, style, or something else. Which of these rules seem to be true in college writing? Which ones are not true in college?

- In what contexts is the five-paragraph essay a useful structure? Why is it not helpful in other contexts—what’s the problem?

Activities

- Put the following “stories” of a thesis in order to make a strong thesis statement:

- Despite their appeal to patients, robotic pets should not be used widely, since they cause more problems than they solve.

- In recent years, robotic pets have been used in medical settings to help children and elderly patients feel emotionally supported and loved.

- Shifting affection to robotic pets rather than live animals suggests a major change in empathy and humanity and could have long-term costs that have not been fully considered.

- Here is a list of one-story theses. Come up with three-story versions of each one.

- Television programming includes content that some find objectionable.

- The percentage of children and youth who are overweight or obese has risen in recent decades.

- First-year college students must learn how to independently manage their time.

- The things we surround ourselves with symbolize who we are.

- Find a scholarly article or book that is interesting to you. Focusing on the abstract and introduction, outline the first, second, and third stories of its thesis.

- Find an example of a five-paragraph theme (online essay mills, your own high school work), produce an alternative three-story thesis, and outline an organically structured paper to carry that thesis out.

Additional Resources

- The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers an excellent, readable rundown on the five-paragraph theme, why most college writing assignments want you to go beyond it, and those times when the simpler structure is actually a better choice.

- There are many useful websites that describe good thesis statements and provide examples. Those from the writing centers at Hamilton College and Purdue University are especially helpful.

Works Cited

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. The Poet at the Breakfast-Table: His Talks with His Fellow-Boarders and the Reader. James R. Osgood, 1872.

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. Pantheon, 1994.

CONTENT FOCUS: Prewriting

Prewriting exercise to help students determine their audience

https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/3656/2021/01/Audience-Analysis-Worksheet-1.pdf

Chapter Focus-

- Discusses connotations, negation, stipulation; includes practice exercises and a sample definition essay

Attributions

- Parts of the above are written by Allison Murray and Anna Mills.

- Parts are adapted from the Writing II unit on definition arguments through Lumen Learning, authored by Cathy Thwing and Eric Aldrich, provided by Pima Community College and shared under a CC BY 4.0 license.