Analysis and Synthesis

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- How to turn information into a thesis and use evidence to support a thesis

- Includes a close reading graphic organizer

What does it mean to know something? How would you explain the process of thinking? In the 1950s, educational theorist Benjamin Bloom proposed that human cognition, thinking and knowing, could be classified by six categories.1 Hierarchically arranged in order of complexity, these steps were:

|

judgment |

most complex |

|

synthesis |

|

|

analysis |

|

|

application |

|

|

comprehension |

|

|

knowledge |

least complex |

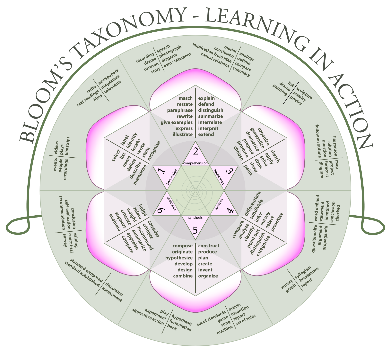

Since his original model, the taxonomy has been revised, as illustrated in the diagram below:

|

Bloom’s Original Design |

|

One Revised Version |

|

judgment |

most complex |

creating |

|

synthesis |

|

evaluating |

|

analysis |

|

analyzing |

|

application |

|

applying |

|

comprehension |

|

understanding |

|

knowledge |

least complex |

remembering |

|

Another Revised Version

|

||

- Each word is an action verb instead of a noun (e.g., “applying” instead of “application”);

- Some words have been changed for different synonyms;

- One version holds “creating” above “evaluating”;

- And, most importantly, other versions are reshaped into a circle, as pictured above.2

What do you think the significance of these changes is?

I introduce this model of cognition to contextualize analysis as a cognitive tool which can work in tandem with other cognitive tasks and behaviors. Analysis is most commonly used alongside synthesis. To proceed with the LEGO® example from Chapter 4, consider my taking apart the castle as an act of analysis. I study each face of each block intently, even those parts that I can’t see when the castle is fully constructed. In the process of synthesis, I bring together certain blocks from the castle to instead build something else—let’s say, a racecar. By unpacking and interpreting each part, I’m able to build a new whole.3

In a text wrestling essay, you’re engaging in a process very similar to my castle-to-racecar adventure. You’ll encounter a text and unpack it attentively, looking closely at each piece of language, its arrangement, its signification, and then use it to build an insightful, critical insight about the original text. I might not use every original block, but by exploring the relationship of part-to-whole, I better understand how the castle is a castle. In turn, I am better positioned to act as a sort of tour guide for the castle or a mechanic for the racecar, able to show my readers what about the castle or racecar is important and to explain how it works.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about crafting a thesis for a text wrestling essay and using evidence to support that thesis. As you will discover, an analytical essay involves every tier of Bloom’s Taxonomy, arguably even including “judgement” because your thesis will present an interpretation that is evidence-based and arguable.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

the cognitive process and/or rhetorical mode of studying constituent parts to demonstrate an interpretation of a larger whole. |

|

|

a part or combination of parts that lends support or proof to an arguable topic, idea, or interpretation. |

|

|

a cognitive and rhetorical process by which an author brings together parts of a larger whole to create a unique new product. Examples of synthesis might include an analytical essay, found poetry, or a mashup/remix. |

|

|

a 1-3 sentence statement outlining the main insight(s), argument(s), or concern(s) of an essay; not necessary in every rhetorical situation; typically found at the beginning of an essay, though sometimes embedded later in the paper. Also referred to as a “So what?” statement. |

|

Techniques

So What? Turning Observations into a Thesis

It’s likely that you’ve heard the term “thesis statement” multiple times in your writing career. Even though you may have some idea what a thesis entails already, it is worth reviewing and unpacking the expectations surrounding a thesis, specifically in a text wrestling essay.

A thesis statement is a central, unifying insight that drives your analysis or argument. In a typical college essay, this insight should be articulated in one to three sentences, placed within the introductory paragraph or section. As we’ll see below, this is not always the case, but it is what many of your audiences will expect. To put it simply, a thesis is the “So what?” of an analytical or persuasive essay. It answers your audience when they ask, Why does your writing matter? What bigger insights does it yield about the subject of analysis? About our world?

Thesis statements in most rhetorical situations advocate for a certain vision of a text, phenomenon, reality, or policy. Good thesis statements support such a vision using evidence and thinking that confirms, clarifies, demonstrates, nuances, or otherwise relates to that vision. In other words, a thesis is “a proposition that you can prove with evidence…, yet it’s one you have to prove, that isn’t obviously true or merely factual.”4

In a text wrestling analysis, a thesis pushes beyond basic summary and observation. In other words, it’s the difference between:

|

Observation |

Thesis |

|

What does the text say? |

What do I have to say about the text? |

|

I noticed ______ |

I noticed ______ and it means ______ |

|

|

I noticed ______ and it matters because ______. |

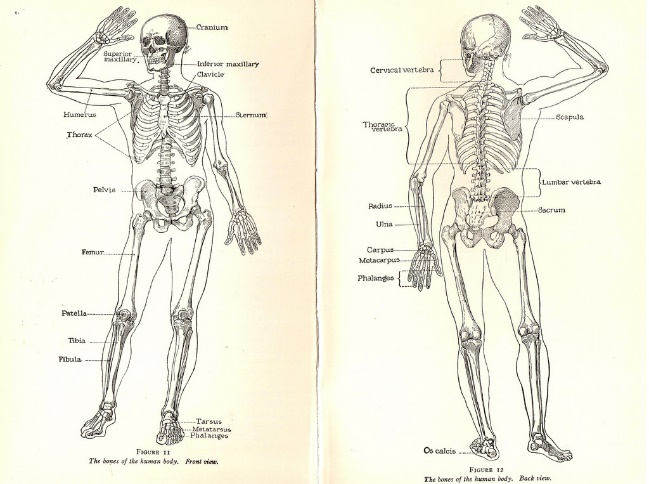

If you think of your essay as the human body, the thesis is the spine. Yes, the body can still exist without a spine, but its functionings will be severely limited. Furthermore, everything comes back to and radiates out from the spine: trace back from your fingertips to your backbone and consider how they relate. In turn, each paragraph should tie back to your thesis, offering support and clear connections so your reader can see the entire “body” of your essay. In this way, a thesis statement serves two purposes: it is not only about the ideas of your paper, but also the structure.

The Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL)5 suggests this specific process for developing your thesis statement:

- Once you’ve read the story or novel closely, look back over your notes for patterns of questions or ideas that interest you. Have most of your questions been about the characters, how they develop or change?

For example:

If you are reading Conrad’s The Secret Agent, do you seem to be most interested in what the author has to say about society? Choose a pattern of ideas and express it in the form of a question and an answer such as the following:

Question: What does Conrad seem to be suggesting about early twentieth-century London society in his novel The Secret Agent?

Answer: Conrad suggests that all classes of society are corrupt.

Pitfalls:

Choosing too many ideas.

Choosing an idea without any support.

- Once you have some general points to focus on, write your possible ideas and answer the questions that they suggest.

For example:

Question: How does Conrad develop the idea that all classes of society are corrupt?

Answer: He uses images of beasts and cannibalism whether he’s describing socialites, policemen or secret agents.

- To write your thesis statement, all you have to do is turn the question and answer around. You’ve already given the answer, now just put it in a sentence (or a couple of sentences) so that the thesis of your paper is clear.

For example:

In his novel, The Secret Agent, Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society.

- Now that you’re familiar with the story or novel and have developed a thesis statement, you’re ready to choose the evidence you’ll use to support your thesis. There are a lot of good ways to do this, but all of them depend on a strong thesis for their direction.

For example:

Here’s a student’s thesis about Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent.

In his novel, The Secret Agent, Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society.

This thesis focuses on the idea of social corruption and the device of imagery. To support this thesis, you would need to find images of beasts and cannibalism within the text.

There are many ways to write a thesis, and your construction of a thesis statement will become more intuitive and nuanced as you become a more confident and competent writer. However, there are a few tried-and-true strategies that I’ll share with you over the next few pages.

The T3 Strategy

T3 is a formula to create a thesis statement. The T (for Thesis) should be the point you’re trying to make—the “So what?” In a text wrestling analysis, you are expected to advocate for a certain interpretation of a text: this is your “So what?” Examples might include:

In “A Wind from the North,” Bill Capossere conveys the loneliness of isolated life

or

Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” suggests that marriage can be oppressive to women

But wait—there’s more! In a text wrestling analysis, your interpretation must be based on evidence from that text. Therefore, your thesis should identify both a focused statement of the interpretation (the whole) and also the particular subjects of your observation (the parts of the text you will focus on support that interpretation). A complete T3 thesis statement for a text wrestling analysis might look more like this:

In “A Wind from the North,” Bill Capossere conveys the loneliness of an isolated lifestyle using the motif of snow, the repeated phrase “five or six days” (104), and the symbol of his uncle’s car.

or

“The Story of an Hour” suggests that marriage can be oppressive to women. To demonstrate this theme, Kate Chopin integrates irony, foreshadowing, and symbols of freedom in the story.

Notice the way the T3 allows for the part-to-whole thinking that underlies analysis:

|

Whole (T) |

Parts (3) |

|

Bill Capossere conveys the loneliness of an isolated lifestyle |

the motif of snow |

|

the repeated phrase “five or six days” (104) |

|

|

the symbol of his uncle’s car. |

|

|

“The Story of an Hour” suggests that marriage can be oppressive to women |

irony |

|

foreshadowing |

|

|

symbols of freedom |

|

This is also a useful strategy because it can provide structure for your paper: each justifying support for your thesis should be one section of your paper.

- Introduction

- Thesis: In “A Wind from the North,” Bill Capossere conveys the loneliness of an isolated lifestyle using the motif of snow, the repeated phrase “five or six days” (104), and the symbol of his uncle’s car.

- Section on ‘the motif of snow.’

Topic sentence: The recurring imagery of snow creates a tone of frostiness and demonstrates the passage of time. - Section on ‘the repeated phrase “five or six days” (104).’

Topic sentence: When Capossere repeats “five or six days” (104), he reveals the ambiguity of death in a life not lived. - Section on ‘the symbol of his uncle’s car.’

Topic sentence: Finally, Capossere’s uncle’s car is symbolic of his lifestyle. - Conclusion

Once you’ve developed a T3 statement, you can revise it to make it feel less formulaic. For example:

In “A Wind from the North,” Bill Capossere conveys the loneliness of an isolated lifestyle by symbolizing his uncle with a “untouchable” car. Additionally, he repeats images and phrases in the essay to reinforce his uncle’s isolation.

or

“The Story of an Hour,” a short story by Kate Chopin, uses a plot twist to imply that marriage can be oppressive to women. The symbols of freedom in the story create a feeling of joy, but the attentive reader will recognize the imminent irony.

The O/P Strategy

An occasion/position thesis statement is rhetorically convincing because it explains the relevance of your argument and concisely articulates that argument. Although you should already have your position in mind, your rhetorical occasion will lead this statement off: what sociohistorical conditions make your writing timely, relevant, applicable? Continuing with the previous examples:

As our society moves from individualism to isolationism, Bill Capossere’s “A Wind from the North” is a salient example of a life lived alone.

or

Although Chopin’s story was written over 100 years ago, it still provides insight to gender dynamics in American marriages.

Following your occasion, state your position—again, this is your “So What?” It is wise to include at least some preview of the parts you will be examining.

As our society moves from individualism to isolationism, Bill Capossere’s “A Wind from the North” is a salient example of a life lived alone. Using recurring images and phrases, Capossere conveys the loneliness of his uncle leading up to his death.

or

Although Chopin’s story was written over 100 years ago, it still provides insight to gender dynamics in American marriages. “The Story of an Hour” reminds us that marriage has historically meant a surrender of freedom for women.

Research Question and Embedded Thesis

There’s one more common style of thesis construction that’s worth noting, and that’s the inquiry-based thesis. (Read more about inquiry-based research writing in Chapter Eight). For this thesis, you’ll develop an incisive and focused question which you’ll explore throughout the course of the essay. By the end of the essay, you will be able to offer an answer (perhaps a complicated or incomplete answer, but still some kind of answer) to the question. This form is also referred to as the “embedded thesis” or “delayed thesis” organization.

Although this model of thesis can be effectively applied in a text wrestling essay, it is often more effective when combined with one of the other methods above.

Consider the following examples:

Bill Capossere’s essay “A Wind from the North” suggests that isolation results in sorrow and loneliness; is this always the case? How does Capossere create such a vision of his uncle’s life?

or

Many people would believe that Kate Chopin’s story reflects an outdated perception of marriage—but can “The Story of an Hour” reveal power imbalances in modern relationships, too?

Synthesis: Using Evidence to Explore Your Thesis

Now that you’ve considered what your analytical insight might be (articulated in the form of a thesis), it’s time to bring evidence in to support your analysis—this is the synthesis part of Bloom’s Taxonomy earlier in this chapter. Synthesis refers to the creation of a new whole (an interpretation) using smaller parts (evidence from the text you’ve analyzed).

There are essentially two ways to go about collecting and culling relevant support from the text with which you’re wrestling. In my experience, students are split about evenly on which option is better for them:

Option #1: Before writing your thesis, while you’re reading and rereading your text, annotate the page and take notes. Copy down quotes, images, formal features, and themes that are striking, exciting, or relatable. Then, try to group your collection of evidence according to common traits. Once you’ve done so, choose one or two groups on which to base your thesis.

Or

Option #2: After writing your thesis, revisit the text looking for quotes, images, and themes that support, elaborate, or explain your interpretation. Record these quotes, and then return to the drafting process.

Once you’ve gathered evidence from your focus text, you should weave quotes, paraphrases, and summaries into your own writing. A common misconception is that you should write “around” your evidence, i.e. choosing the direct quote you want to use and building a paragraph around it. Instead, you should foreground your interpretation and analysis, using evidence in the background to explore and support that interpretation. Lead with your idea, then demonstrate it with evidence; then, explain how your evidence demonstrates your idea.

The appropriate ratio of evidence (their writing) to exposition (your writing) will vary depending on your rhetorical situation, but I advise my students to spend at least as many words unpacking a quote as that quote contains. (I’m referring here to Step #4 in the table below.) For example, if you use a direct quote of 25 words, you ought to spend at least 25 words explaining how that quote supports or nuances your interpretation.

There are infinite ways to bring evidence into your discussion,6 but for now, let’s take a look at a formula that many students find productive as they find their footing in analytical writing: Front-load + Quote/Paraphrase/Summarize + Cite + Explain/elaborate/analyze.

|

1. front-load (1-2 sentences) |

+ |

2. quote, paraphrase, or summarize |

+ |

3. (cite) |

+ |

4. explain, elaborate, analyze (2-3 sentences) |

|

Set your reader up for the quote using a signpost (also known as a signal phrase; see Chapter Nine). Don’t drop quotes in abruptly: by front-loading, you can guide your reader’s interpretation. |

|

Use whichever technique is relevant to your rhetorical purpose at that exact point. |

|

Use an in-text citation appropriate to your discipline. It doesn’t matter if you quote, paraphrase, or summarize—all three require a citation. |

|

Perhaps most importantly, you need to make the value of this evidence clear to the reader. What does it mean? How does it further your thesis? |

What might this look like in practice?

The recurring imagery of snow creates a tone of frostiness and demonstrates the passage of time. (1) Snow brings to mind connotations of wintery cold, quiet, and death (2) as a “sky of utter clarity and simplicity” lingers over his uncle’s home and “it [begins] once more to snow” ((3) Capossere 104). (4) Throughout his essay, Capossere returns frequently to weather imagery, but snow especially, to play on associations the reader has. In this line, snow sets the tone by wrapping itself in with “clarity,” a state of mind. Even though the narrator still seems ambivalent about his uncle, this clarity suggests that he is reflecting with a new and somber understanding.

- Front-load

Snow brings to mind connotations of wintery cold, quiet, and death - Quote

as a “sky of utter clarity and simplicity” lingers over his uncle’s home and “it [begins] once more to snow” - Cite

(Capossere 104). - Explain/elaborate/analysis

Throughout his essay, Capossere returns frequently to weather imagery, but snow especially, to play on associations the reader has. In this line, snow sets the tone by wrapping itself in with “clarity,” a state of mind. Even though the narrator still seems ambivalent about his uncle, this clarity suggests that he is reflecting with a new and somber understanding.

This might feel formulaic and forced at first, but following these steps will ensure that you give each piece of evidence thorough attention. Some teachers call this method a “quote sandwich” because you put your evidence between two slices of your own language and interpretation.

For more on front-loading (readerly signposts or signal phrases), see the subsection titled “Readerly Signposts” in Chapter Nine.

Activities

Idea Generation: Close Reading Graphic Organizer

The first time you read a text, you most likely will not magically stumble upon a unique, inspiring insight to pursue as a thesis. As discussed earlier in this section, close reading is an iterative process, which means that you must repeatedly encounter a text (reread, re-watch, re-listen, etc.) trying to challenge it, interrogate it, and gradually develop a working thesis.

Very often, the best way to practice analysis is collaboratively, through discussion. Because other people will necessarily provide different perspectives through their unique interpretive positions, reading groups can help you grow your analysis. By discussing a text, you open yourself up to more nuanced and unanticipated interpretations influenced by your peers. Your teacher might ask you to work in small groups to complete the following graphic organizer in response to a certain text. (You can also complete this exercise independently, but it might not yield the same results.)

|

Title and Author of Text: |

Group Members’ Names:

|

|

|

Start by “wading” back through the text. Remind yourself of the general idea and annotate important words, phrases, and passages. |

||

|

As a group, discuss and explain: What could the meaning or message of this text be? What ideas does the text communicate? (Keep in mind, there are an infinite number of “right” answers here.) |

||

|

What patterns do you see in the text (e.g., repetition of words, phrases, sentences, or images; ways that the text is structured)? What breaks in the patterns do you see? What is the effect of these patterns and breaks of pattern? |

||

|

What symbols and motifs do you see in the text? What might they represent? What is the effect of these symbols? What themes do they cultivate or gesture to? |

||

|

What references do you see in the text? Does the author allude to, quote, imitate, or parody another text, film, song, etc.? Does the author play on connotations? What is the effect of these references? |

||

|

What about this text surprises you? What do you get hung up on? Consider Jane Gallop’s brief list from “The Ethics of Reading: Close Encounters” – (1) unusual vocabulary, words that surprise either because they are unfamiliar or because they seem to belong to a different context; (2) words that seem unnecessarily repeated, as if the word keeps insisting on being written; (3) images or metaphors, especially ones that are used repeatedly and are somewhat surprising given the context; (4) what is in italics or parentheses; and (5) footnotes that seem too long7 – but also anything else that strikes you as a reader.

|

||

|

Analytical lenses: Do you see any of the following threads represented in the work? What evidence of these ideas do you see? How do these parts contribute to a whole? |

||

|

Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality |

Gender and Sexuality |

|

|

Disability |

Social Class and Economy |

|

|

Ecologies and the Environment |

(Post)colonialism |

|

Thesis Builder

Your thesis statement can and should evolve as you continue writing your paper: teachers will often refer to a thesis as a “working thesis” because the revision process should include tweaking, pivoting, focusing, expanding, and/or rewording your thesis. The exercise on the next two pages, though, should help you develop a working thesis to begin your project. Following the examples, identify the components of your analysis that might contribute to a thesis statement.

|

Topic (Name your focus text and its author) |

Ex.: “A Wind from the North” by Bill Capossere |

|

Analytical focus (Identify at least one part of the whole you’re studying) |

Ex.: Repeated phrase “five or six days” (104) Motif – snow |

|

Analytical insight (Explain the function of that part in relationship to the whole) |

Ex.: They imply that living in isolation makes you lonely

|

|

Stakes (So what? Why does it matter?) |

Ex.: Sheds light on the fragility of life and the relationships we build throughout it. |

|

Consider adding… A concession statement (“Although,” “even though,” etc.) Ex.: Although there’s nothing wrong with preferring time alone, … A question that you might pursue Ex.: Can Capossere’s uncle represent other isolated people? |

|

|

THESIS: Ex.: Although there’s nothing wrong with preferring time alone, “A Wind from the North” by Bill Capossere sheds light on the fragility of life and the relationships we build throughout it. The text conveys the loneliness of an isolated lifestyle by symbolizing Capossere’s uncle with a “untouchable” car. Additionally, the narrator repeats images and phrases in the essay to reinforce his uncle’s isolation. |

|

Model Texts by Student Authors

Songs8

(A text wrestling analysis of “Proofs” by Richard Rodriguez)

Songs are culturally important. In the short story “Proofs” by Richard Rodriguez, a young Mexican American man comes to terms with his bi-cultural life. This young man’s father came to America from a small and poverty-stricken Mexican village. The young man flashes from his story to his father’s story in order to explore his Mexican heritage and American life. Midway through the story Richard Rodriguez utilizes the analogies of songs to represent the cultures and how they differ. Throughout the story there is a clash of cultures. Because culture can be experienced through the arts and teachings of a community, Rodriguez uses the songs of the two cultures to represent the protagonist’s bi-cultural experience.

According to Rodriguez, the songs that come from Mexico express an emotional and loving culture and community: “But my mama says there are no songs like the love songs of Mexico” (50). The songs from that culture can be beautiful. It is amazing the love and beauty that come from social capital and community involvement. The language Richard Rodriguez uses to explain these songs is beautiful as well. “—it is the raw edge of sentiment” (51). The author explains how it is the men who keep the songs. No matter how stoic the men are, they have an outlet to express their love and pain as well as every emotion in between. “The cry of a Jackal under the moon, the whistle of a phallus, the maniacal song of the skull” (51). This is an outlet for men to express themselves that is not prevalent in American culture. It expresses a level of love and intimacy between people that is not a part of American culture. The songs from the American culture are different. In America the songs get lost. There is assimilation of cultures. The songs of Mexico are important to the protagonist of the story. There is a clash between the old culture in Mexico and the subject’s new American life represented in these songs.

A few paragraphs later in the story, on page 52, the author tells us the difference in the American song. America sings a different tune. America is the land of opportunity. It represents upward mobility and the ability to “make it or break it.” But it seems there is a cost for all this material gain and all this opportunity. There seems to be a lack of love and emotion, a lack of the ability to express pain and all other feelings, the type of emotion which is expressed in the songs of Mexico. The song of America says, “You can be anything you want to be” (52). The song represents the American Dream. The cost seems to be the loss of compassion, love and emotion that is expressed through the songs of Mexico. There is no outlet quite the same for the stoic men of America. Rodriguez explains how the Mexican migrant workers have all that pain and desire, all that emotion penned up inside until it explodes in violent outbursts. “Or they would come into town on Monday nights for the wrestling matches or on Tuesdays for boxing. They worked over in Yolo County. They were men without women. They were Mexicans without Mexico” (49).

Rodriguez uses the language in the story almost like a song in order to portray the culture of the American dream. The phrase “I will send for you or I will come home rich,” is repeated twice throughout the story. The gain for all this loss of love and compassion is the dream of financial gain. “You have come into the country on your knees with your head down. You are a man” (48). That is the allure of the American Dream.

The protagonist of the story was born in America. Throughout the story he is looking at this illusion of the American Dream through a different frame. He is also trying to come to terms with his own manhood in relation to his American life and Mexican heritage. The subject has the ability to see the two songs in a different light. “The city will win. The city will give the children all the village could not-VCR’s, hairstyles, drumbeat. The city sings mean songs, dirty songs” (52). Part of the subject’s reconciliation process with himself is seeing that all the material stuff that is dangled as part of the American Dream is not worth the love and emotion that is held in the old Mexican villages and expressed in their songs.

Rodriguez represents this conflict of culture on page 53. The protagonist of the story is taking pictures during the arrest of illegal border-crossers. “I stare at the faces. They stare at me. To them I am not bearing witness; I am part of the process of being arrested”(53). The subject is torn between the two cultures in a hazy middle ground. He is not one of the migrants and he is not one of the police. He is there taking pictures of the incident with a connection to both of the groups and both of the groups see him connected with the other.

The old Mexican villages are characterized by a lack of: “Mexico is poor” (50). However, this is not the reason for the love and emotion that is held. The thought that people have more love and emotion because they are poor is a misconception. There are both rich people and poor people who have multitudes of love and compassion. The defining elements in creating love and emotion for each other comes from the level of community interaction and trust—the ability to sing these love songs and express emotion towards one another. People who become caught up in the American Dream tend to be obsessed with their own personal gain. This diminishes the social interaction and trust between fellow humans. There is no outlet in the culture of America quite the same as singing love songs towards each other. It does not matter if they are rich or poor, lack of community, trust, and social interaction; lack of songs can lead to lack of love and emotion that is seen in the old songs of Mexico.

The image of the American Dream is bright and shiny. To a young boy in a poor village the thought of power and wealth can dominate over a life of poverty with love and emotion. However, there is poverty in America today as well as in Mexico. The poverty here looks a little different but many migrants and young men find the American Dream to be an illusion. “Most immigrants to America came from villages.

The America that Mexicans find today, at the decline of the century, is a closed-circuit city of ramps and dark towers, a city without God. The city is evil. Turn. Turn” (50). The song of America sings an inviting tune for young men from poor villages. When they arrive though it is not what they dreamed about. The subject of the story can see this. He is trying to come of age in his own way, acknowledging America and the Mexico of old. He is able to look back and forth in relation to the America his father came to for power and wealth and the America that he grew up in. All the while, he watches this migration of poor villages, filled with love and emotion, to a big heartless city, while referring back to his father’s memory of why he came to America and his own memories of growing up in America. “Like wandering Jews. They carried their home with them, back and forth: they had no true home but the tabernacle of memory” (51). The subject of the story is experiencing all of this conflict of culture and trying to compose his own song.

Works Cited

Rodriguez, Richard. “Proofs.” In Short: A Collection of Brief Creative Nonfiction, edited by Judith Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones, Norton, 1996, pp. 48-54.

Normal Person: An Analysis of the Standards of Normativity in “A Plague of Tics”9

David Sedaris’ essay “A Plague of Tics” describes Sedaris’ psychological struggles he encountered in his youth, expressed through obsessive-compulsive tics. These abnormal behaviors heavily inhibited his functionings, but more importantly, isolated and embarrassed him during his childhood, adolescence, and young adult years. Authority figures in his life would mock him openly, and he constantly struggled to perform routine simple tasks in a timely manner, solely due to the amount of time that needed to be set aside for carrying out these compulsive tics. He lacked the necessary social support an adolescent requires because of his apparent abnormality. But when we look at the behaviors of his parents, as well as the socially acceptable tics of our society more generally, we see how Sedaris’ tics are in fact not too different, if not less harmful than those of the society around him. By exploring Sedaris’ isolation, we can discover that socially constructed standards of normativity are at best arbitrary, and at worst violent.

As a young boy, Sedaris is initially completely unaware that his tics are not socially acceptable in the outside world. He is puzzled when his teacher, Miss Chestnut, correctly guesses that he is “going to hit [himself] over the head with [his] shoe” (361), despite the obvious removal of his shoe during their private meeting. Miss Chestnut continues by embarrassingly making fun out of the fact that Sedaris’ cannot help but “bathe her light switch with [his] germ-ridden tongue” (361) repeatedly throughout the school day. She targets Sedaris with mocking questions, putting him on the spot in front of his class; this behavior is not ethical due to Sedaris’ age. It violates the trust that students should have in their teachers and other caregivers. Miss Chestnut criticizes him excessively for his ambiguous, child-like answers. For example, she drills him on whether it is “healthy to hit ourselves over the head with our shoes” (361) and he “guess[es] that it was not,” (361) as a child might phrase it. She ridicules his use of the term “guess,” using obvious examples of instances when guessing would not be appropriate, such as “[running] into traffic with a paper sack over [her] head” (361). Her mockery is not only rude, but ableist and unethical. Any teacher—at least nowadays—should recognize that Sedaris needs compassion and support, not emotional abuse.

These kinds of negative responses to Sedaris’ behavior continue upon his return home, in which the role of the insensitive authority figure is taken on by his mother. In a time when maternal support is crucial for a secure and confident upbringing, Sedaris’ mother was never understanding of his behavior, and left little room for open, honest discussion regarding ways to cope with his compulsiveness. She reacted harshly to the letter sent home by Miss Chestnut, nailing Sedaris, exclaiming that his “goddamned math teacher” (363) noticed his strange behaviors, as if it should have been obvious to young, egocentric Sedaris. When teachers like Miss Chestnut meet with her to discuss young David’s problems, she makes fun of him, imitating his compulsions; Sedaris is struck by “a sharp, stinging sense of recognition” upon viewing this mockery (365). Sedaris’ mother, too, is an authority figure who maintains ableist standards of normativity by taunting her own son. Meeting with teachers should be an opportunity to truly help David, not tease him.

On the day that Miss Chestnut makes her appearance in the Sedaris household to discuss his behaviors with his mother, Sedaris watches them from the staircase, helplessly embarrassed. We can infer from this scene that Sedaris has actually become aware of that fact that his tics are not considered to be socially acceptable, and that he must be “the weird kid” among his peers—and even to his parents and teachers. His mother’s cavalier derision demonstrates her apparent disinterest in the well-being of he son, as she blatantly brushes off his strange behaviors except in the instance during which she can put them on display for the purpose of entertaining a crowd. What all of these pieces of his mother’s flawed personality show us is that she has issues too—drinking and smoking, in addition to her poor mothering—but yet Sedaris is the one being chastised while she lives a normal life. Later in the essay, Sedaris describes how “a blow to the nose can be positively narcotic” (366), drawing a parallel to his mother’s drinking and smoking. From this comparison, we can begin to see flawed standards of “normal behavior”: although many people drink and smoke (especially at the time the story takes place), these habits are much more harmful than what Sedaris does in private.

Sedaris’ father has an equally harmful personality, but it manifests differently. Sedaris describes him as a hoarder, one who has, “saved it all: every last Green Stamp and coupon, every outgrown bathing suit and scrap of linoleum” (365). Sedaris’ father attempts to “cure [Sedaris] with a series of threats” (366). In one scene, he even enacts violence upon David by slamming on the brakes of the car while David has his nose pressed against a windshield. Sedaris reminds us that his behavior might have been unusual, but it wasn’t violent: “So what if I wanted to touch my nose to the windshield? Who was I hurting?” (366). In fact, it is in that very scene that Sedaris draws the aforementioned parallel to his mother’s drinking: when Sedaris discovers that “a blow to the nose can be positively narcotic,” it is while his father is driving around “with a lapful of rejected, out-of-state coupons” (366). Not only is Sedaris’ father violating the trust David places in him as a caregiver; his hoarding is an arguably unhealthy habit that simply happens to be more socially acceptable than licking a concrete toadstool. Comparing Sedaris’s tics to his father’s issues, it is apparent that his father’s are much more harmful than his own. None of the adults in Sedaris’ life are innocent—“mother smokes and Miss Chestnut massaged her waist twenty, thirty times a day—and here I couldn’t press my nose against the windshield of a car” (366)—but nevertheless, Sedaris’s problems are ridiculed or ignored by the ‘normal’ people in his life, again bringing into question what it means to be a normal person.

In high school, Sedaris’ begins to take certain measures to actively control and hide his socially unacceptable behaviors. “For a time,” he says, “I thought that if I accompanied my habits with an outlandish wardrobe, I might be viewed as eccentric rather than just plain retarded” (369). Upon this notion, Sedaris starts to hang numerous medallions around his neck, reflecting that he “might as well have worn a cowbell” (369) due to the obvious noises they made when he would jerk his head violently, drawing more attention to his behaviors (the opposite of the desired effect). He also wore large glasses, which he now realizes made it easier to observe his habit of rolling his eyes into his head, and “clunky platform shoes [that] left lumps when used to discreetly tap [his] forehead” (369). Clearly Sedaris was trying to appear more normal, in a sense, but was failing terribly. After high school, Sedaris faces the new wrinkle of sharing a college dorm room. He conjures up elaborate excuses to hide specific tics, ensuring his roommate that “there’s a good chance the brain tumor will shrink” (369) if he shakes his head around hard enough and that specialists have ordered him to perform “eye exercises to strengthen what they call he ‘corneal fibers’” (369). He eventually comes to a point of such paranoid hypervigilance that he memorizes his roommate’s class schedule to find moments to carry out his tics in privacy. Sedaris worries himself sick attempting to approximate ‘normal’: “I got exactly fourteen minutes of sleep during my entire first year of college” (369). When people are pressured to perform an identity inconsistent with their own—pressured by socially constructed standards of normativity—they harm themselves in the process. Furthermore, even though the responsibility does not necessarily fall on Sedaris’ peers to offer support, we can assume that their condemnation of his behavior reinforces the standards that oppress him.

Sedaris’ compulsive habits peak and begin their slow decline when he picks up the new habit of smoking cigarettes, which is of course much more socially acceptable while just as compulsive in nature once addiction has the chance to take over. He reflects, from the standpoint of an adult, on the reason for the acquired habit, speculating that “maybe it was coincidental, or perhaps … much more socially acceptable than crying out in tiny voices” (371). He is calmed by smoking, saying that “everything’s fine as long I know there’s a cigarette in my immediate future” (372). (Remarkably, he also reveals that he has not truly been cured, as he revisits his former tics and will “dare to press [his] nose against the doorknob or roll his eyes to achieve that once-satisfying ache” [372.]) Sedaris has officially achieved the tiresome goal of appearing ‘normal’, as his compulsive tics seemed to “[fade] out by the time [he] took up with cigarettes” (371). It is important to realize, however, that Sedaris might have found a socially acceptable way to mask his tics, but not a healthy one. The fact that the only activity that could take place of his compulsive tendencies was the dangerous use of a highly addictive substance, one that has proven to be dangerously harmful with frequent and prolonged use, shows that he is conforming to the standards of society which do not correspond with healthy behaviors.

In a society full of dangerous, inconvenient, or downright strange habits that are nevertheless considered socially acceptable, David Sedaris suffered through the psychic and physical violence and negligence of those who should have cared for him. With what we can clearly recognize as a socially constructed disability, Sedaris was continually denied support and mocked by authority figures. He struggled to socialize and perform academically while still carrying out each task he was innately compelled to do, and faced consistent social hardship because of his outlandish appearance and behaviors that are viewed in our society as “weird.” Because of ableist, socially constructed standards of normativity, Sedaris had to face a long string of turmoil and worry that most of society may never come to completely understand. We can only hope that as a greater society, we continue sharing and studying stories like Sedaris’ so that we critique the flawed guidelines we force upon different bodies and minds, and attempt to be more accepting and welcoming of the idiosyncrasies we might deem to be unfavorable.

Teacher Takeaways

“The student clearly states their thesis in the beginning, threading it through the essay, and further developing it through a synthesized conclusion. The student’s ideas build logically through the essay via effective quote integration: the student sets up the quote, presents it clearly, and then responds to the quote with thorough analysis that links it back to their primary claims. At times this thread is a bit difficult to follow; as one example, when the student talks about the text’s American songs, it’s not clear how Rodriguez’s text illuminates the student’s thesis. Nor is it clear why the student believes Rodriguez is saying the “American Dream is not worth the love and emotion.” Without this clarification, it’s difficult to follow some of the connections the student relies on for their thesis, so at times it seems like they may be stretching their interpretation beyond what the text supplies.”– Professor Dannemiller

Teacher Takeaways

“I like how this student follows their thesis through the text, highlighting specific instances from Sedaris’s essay that support their analysis. Each instance of this evidence is synthesized with the student’s observations and connected back to their thesis statement, allowing for the essay to capitalize on the case being built in their conclusion. At the ends of some earlier paragraphs, some of this ‘spine-building’ is interrupted with suggestions of how characters in the essay should behave, which doesn’t always clearly link to the thesis’s goals. Similarly, some information isn’t given a context to help us understand its relevance, such as what violating the student-teacher trust has to do with normativity being a social construct, or how Sedaris’s description of ‘a blow to the nose’ being a narcotic creates a parallel to his mother’s drinking and smoking. Without further analysis and synthesis of this information the reader is left to guess how these ideas connect.”– Professor Dannemiller

Works Cited

Sedaris, David. “A Plague of Tics.” 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology, 4th edition, edited by Samuel Cohen, Bedford, 2013, pp. 359-372.

Analyzing “Richard Cory”10

In the poem “Richard Cory” by Edward Arlington Robinson, a narrative is told about the character Richard Cory by those who admired him. In the last stanza, the narrator, who uses the pronoun “we,” tells us that Richard Cory commits suicide. Throughout most of the poem, though, Cory had been described as a wealthy gentleman. The “people on the pavement” (2), the speakers of the poem, admired him because he presented himself well, was educated, and was wealthy. The poem presents the idea that, even though Cory seemed to have everything going for him, being wealthy does not guarantee happiness or health.

Throughout the first three stanzas Cory is described in a positive light, which makes it seem like he has everything that he could ever need. Specifically, the speaker compares Cory directly and indirectly to royalty because of his wealth and his physical appearance: “He was a gentleman from sole to crown, / Clean favored and imperially slim” (Robinson 3-4). In line 3, the speaker is punning on “soul” and “crown.” At the same time, Cory is both a gentleman from foot (sole) to head (crown) and also soul to crown. The use of the word “crown” instead of head is a clever way to show that Richard was thought of as a king to the community. The phrase “imperially slim” can also be associated with royalty because imperial comes from “empire.” The descriptions used gave clear insight that he was admired for his appearance and manners, like a king or emperor.

In other parts of the poem, we see that Cory is ‘above’ the speakers. The first lines, “When Richard Cory went down town, / We people on the pavement looked at him” (1-2), show that Cory is not from the same place as the speakers. The words “down” and “pavement” also suggest a difference in status between Cory and the people. The phrase “We people on the pavement” used in the first stanza (Robinson 2), tells us that the narrator and those that they are including in their “we” may be homeless and sleeping on the pavement; at the least, this phrase shows that “we” are below Cory.

In addition to being ‘above,’ Cory is also isolated from the speakers. In the second stanza, we can see that there was little interaction between Cory and the people on the pavement: “And he was always human when he talked; / But still fluttered pulses when he said, / ‘Good- morning’” (Robinson 6-8). Because people are “still fluttered” by so little, we can speculate that it was special for them to talk to Cory. But these interactions gave those on the pavement no insight into Richard’s real feelings or personality. Directly after the descriptions of the impersonal interactions, the narrator mentions that “he was rich—yes, richer than a king” (Robinson 9). At the same time that Cory is again compared to royalty, this line reveals that people were focused on his wealth and outward appearance, not his personal life or wellbeing.

The use of the first-person plural narration to describe Cory gives the reader the impression that everyone in Cory’s presence longed to have the life that he did. Using “we,” the narrator speaks for many people at once. From the end of the third stanza to the end of the poem, the writing turns from admirable description of Richard to a noticeably more melancholy, dreary description of what those who admired Richard had to do because they did not have all that Richard did. These people had nothing, but they thought that he was everything. To make us wish that we were in his place. So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread…. (Robinson 9-12)

They sacrificed their personal lives and food to try to rise up to Cory’s level. They longed to not be required to struggle. A heavy focus on money and materialistic things blocked their ability to see what Richard Cory was actually feeling or going through. I suggest that “we” also includes the reader of the poem. If we read the poem this way, “Richard Cory” critiques the way we glorify wealthy people’s lives to the point that we hurt ourselves. Our society values financial success over mental health and believes in a false narrative about social mobility.

Though the piece was written more than a century ago, the perceived message has not been lost. Money and materialistic things do not create happiness, only admiration and alienation from those around you. Therefore, we should not sacrifice our own happiness and leisure for a lifestyle that might not make us happy. The poem’s message speaks to our modern society, too, because it shows a stigma surrounding mental health: if people have “everything / To make us wish that we were in [their] place” (11-12), we often assume that they don’t deal with the same mental health struggles as everyone. “Richard Cory” reminds us that we should take care of each other, not assume that people are okay because they put up a good front.

Teacher Takeaways

“I enjoy how this author uses evidence: they use a signal phrase (front-load) before each direct quote and take plenty of time to unpack the quote afterward. This author also has a clear and direct thesis statement which anticipates the content of their analysis. I would advise them, though, to revise that thesis by ‘previewing’ the elements of the text they plan to analyze. This could help them clarify their organization, since a thesis should be a road-map.”– Professor Wilhjelm

Works Cited

Robinson, Edward Arlington. “Richard Cory.” The Norton Introduction to Literature, Shorter 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, Norton, 2017, p. 482.

Endnotes

Media Attributions

- lego-car

Once you decide on a method for organizing your essay, you’ll want to start drafting your paragraphs. Think of your paragraphs as links in a chain where coherence and continuity are key. Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. You are likely to lose interest in a piece of writing that is disorganized and spans many pages without breaks. Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks, each paragraph focusing on only one main idea and presenting coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. For most types of informative or persuasive academic writing, writers find it helpful to think of the paragraph analogous to an essay, as each is controlled by a main idea or point, and that idea is developed by an organized group of more specific ideas. Thus, the thesis of the essay is analogous to the topic sentence of a paragraph, just as the supporting sentences in a paragraph are analogous to the supporting paragraphs in an essay.

In essays, each supporting paragraph adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related supporting idea is developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis. Effective paragraphing makes the difference between a satisfying essay that readers can easily process and one that requires readers to mentally organize the piece themselves. Thoughtful organization and development of each body paragraph leads to an effectively focused, developed, and coherent essay.

An effective paragraph contains three main parts:

- a topic sentence

- body, supporting sentences

- a concluding sentence

In informative and persuasive writing, the topic sentence is usually the first or second sentence of a paragraph and expresses its main idea, followed by supporting sentences that help explain, prove, or enhance the topic sentence. In narrative and descriptive paragraphs, however, topic sentences may be implied rather than explicitly stated, with all supporting sentences working to create the main idea. If the paragraph contains a concluding sentence, it is the last sentence in the paragraph and reminds the reader of the main point by restating it in different words.

Creating Focused Paragraphs with Topic Sentences

The foundation of a paragraph is the topic sentence which expresses the main idea or point of the paragraph. A topic sentence functions in two ways: it clearly refers to and supports the essay’s thesis, and it indicates what will follow in the rest of the paragraph. As the unifying sentence for the paragraph, it is the most general sentence, whereas all supporting sentences provide different types of more specific information such as facts, details, or examples.

An effective topic sentence has the following characteristics:

- A topic sentence provides an accurate indication of what will follow in the rest of the paragraph.

Weak Example

First, we need a better way to educate students.

Explanation: The claim is vague because it does not provide enough information about what will follow and it is too broad to be covered effectively in one paragraph.

Stronger Example

Creating a national set of standards for math and English education will improve student learning in many states.

Explanation: The sentence replaces the vague phrase “a better way” and leads readers to expect supporting facts and examples as to why standardizing education in these subjects might improve student learning in many states.

- A good topic sentence is the most general sentence in the paragraph and thus does not include supporting details.

Weak Example

Salaries should be capped in baseball for many reasons, most importantly so we don’t allow the same team to win year after year.

Explanation: This topic sentence includes a supporting detail that should be included later in the paragraph to back up the main point.

Stronger Example

Introducing a salary cap would improve the game of baseball for many reasons.

Explanation: This topic sentence omits the additional supporting detail so that it can be expanded upon later in the paragraph, yet the sentence still makes a claim about salary caps – improvement of the game.

- A good topic sentence is clear and easy to follow.

Weak Example

In general, writing an essay, thesis, or other academic or nonacademic document is considerably easier and of much higher quality if you first construct an outline, of which there are many different types.

Explanation: The confusing sentence structure and unnecessary vocabulary bury the main idea, making it difficult for the reader to follow the topic sentence.

Stronger Example

Most forms of writing can be improved by first creating an outline.

Explanation: This topic sentence cuts out unnecessary verbiage and simplifies the previous statement, making it easier for the reader to follow. The writer can include examples of what kinds of writing can benefit from outlining in the supporting sentences.

Location of Topic Sentences

As previously discussed, a topic sentence can appear anywhere within a paragraph depending upon the mode of writing, or it can be implied such as in narrative or descriptive writing. In college-level expository or persuasive writing, placing an explicit topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph (the first or second sentence) makes it easier for readers to follow the essay and for writers to stay on topic, but writers should be aware of variations and maintain the flexibility to adapt to different writing projects. The following examples illustrate varying locations for the topic sentence. In each example, the topic sentence is underlined.

Topic Sentence Begins the Paragraph (General to Specific)

After seeing an ad for a new ABC show on Hulu this week I wondered why we are still being bombarded with reality shows on multiple platforms. Along with the return of viewer favorites, we are to be cursed with yet another mindless creation. The Golden Bachelor features a 71 year old bachelor and his 65-and-older potential romantic partners. A promo for the first episode highlights stereotypical generational differences between the main love interest and usual "bachelors," emphasizing the show's attempt at uniqueness. For instance, the promo claims, "his DMs have postage," and "if you call him, he'll answer the phone."[1] Articles about the show seem to continually mention the purported demand for this spinoff and the producers' need for the "right" bachelor. I dread to think what producers will come up with in future years and hope that other viewers will express their criticism of yet more false romances leading to unhealthy relationships. These producers must stop the constant stream of meaningless shows without plotlines. We’ve had enough reality television to last us a lifetime.

The first sentence tells readers that the paragraph will be about reality television shows, and it expresses the writer’s distaste for these shows through the use of the word bombarded. Each of the following sentences in the paragraph supports the topic sentence by providing further information about a specific reality television show and why the writer finds it unappealing. The final sentence is the concluding sentence. It reiterates the main point that viewers are bored with reality television shows by using different words from the topic sentence.

Paragraphs that begin with the topic sentence move from the general to the specific. They open with a general statement about a subject (reality shows) and then discuss specific examples (the reality show The Golden Bachelor). Most academic essays contain the topic sentence at the beginning of the first paragraph. However, when utilizing a specific to general method, the topic sentence may be located later in the paragraph.

Topic Sentence Ends the Paragraph (Specific to General)

Last year, a cat traveled 130 miles to reach its family who had moved to another state and had left their pet behind. Even though it had never been to their new home, the cat was able to track down its former owners. A dog in my neighborhood can predict when its master is about to have a seizure. It makes sure that he does not hurt himself during an epileptic fit. Compared to many animals, our own senses are almost dull.

The last sentence of this paragraph is the topic sentence. It draws on specific examples (a cat that tracked down its owners and a dog that can predict seizures) and then makes a general statement that draws a conclusion from these examples (animals’ senses are better than humans’). In this case, the supporting sentences are placed before the topic sentence, and the concluding sentence is the same as the topic sentence. This technique is frequently used in persuasive writing. The writer produces detailed examples as evidence to back up his or her point, preparing the reader to accept the concluding topic sentence as the truth.

When the Topic Sentence Appears in the Middle of the Paragraph

For many years, I suffered from severe anxiety every time I took an exam. Hours before the exam, my heart would begin pounding, my legs would shake, and sometimes I would become physically unable to move. Last year, I was referred to a specialist and finally found a way to control my anxiety—breathing exercises. It seems so simple, but by doing just a few breathing exercises a couple of hours before an exam, I gradually got my anxiety under control. The exercises help slow my heart rate and make me feel less anxious. Better yet, they require no pills, no equipment, and very little time. It’s amazing how just breathing correctly has helped me learn to manage my anxiety symptoms.

In this paragraph, the underlined sentence is the topic sentence. It expresses the main idea—that breathing exercises can help control anxiety. The preceding sentences enable the writer to build up to his main point (breathing exercises can help control anxiety) by using a personal anecdote (how he used to suffer from anxiety). The supporting sentences then expand on how breathing exercises help the writer by providing additional information. The last sentence is the concluding sentence and restates how breathing can help manage anxiety. Placing a topic sentence in the middle of a paragraph is often used in creative writing. If you notice that you have used a topic sentence in the middle of a paragraph in an academic essay, read through the paragraph carefully to make sure that it contains only one major topic.

Implied Topic Sentences

Some well-organized paragraphs do not contain a topic sentence at all, a technique often used in descriptive and narrative writing. Instead of being directly stated, the main idea is implied in the content of the paragraph, as in the following narrative paragraph.

Example of Implied Topic Sentence

Heaving herself up the stairs, Luella had to pause for breath several times. She let out a wheeze as she sat down heavily in the wooden rocking chair. Tao approached her cautiously, as if she might crumble at the slightest touch. He studied her face, like parchment, stretched across the bones so finely he could almost see right through the skin to the decaying muscle underneath. Luella smiled a toothless grin.

Although no single sentence in this paragraph states the main idea, the entire paragraph focuses on one concept—that Luella is extremely old. The topic sentence is thus implied rather than stated so that all the details in the paragraph can work together to convey the dominant impression of Luella’s age. In a paragraph such as this one, an explicit topic sentence would seem awkward and heavy-handed. Implied topic sentences work well if the writer has a firm idea of what he or she intends to say in the paragraph and sticks to it. However, a paragraph loses its effectiveness if an implied topic sentence is too subtle or the writer loses focus.

Developing Paragraphs

If you think of a paragraph as a sandwich, the supporting sentences are the filling between the bread. They make up the body of the paragraph by explaining, proving, or enhancing the controlling idea in the topic sentence. The overall method of development for paragraphs depends upon the essay as a whole and the purpose of each paragraph; thus paragraphs may be developed by using examples, description, narration, comparison and contrast, definition, cause and effect, classification and division. A writer may use one method or combine several methods.

Writers often want to know how many words a paragraph should contain, and the answer is that a paragraph should develop the idea, point, or impression completely enough to satisfy the writer and readers. Depending on their function, paragraphs can vary in length from one or two sentences, to over a page; however, in most college assignments, successfully developed paragraphs usually contain approximately one hundred to two hundred and fifty words and span one-fourth to two-thirds of a typed page. A series of short paragraphs in an academic essay can seem choppy and unfocused, whereas paragraphs that are one page or longer can tire readers. Giving readers a paragraph break on each page helps them maintain focus.

This advice does not mean, of course, that composing a paragraph of a particular number of words or sentences guarantees an effective paragraph. Writers must provide enough supporting sentences within paragraphs to develop the topic sentence and simultaneously carry forward the essay’s main idea.

For example, in a descriptive paragraph about a room in the writer’s childhood home, a length of two or three sentences is unlikely to contain enough details to create a picture of the room in the reader’s mind, and it will not contribute in conveying the meaning of the place. In contrast, a half page paragraph, full of carefully selected vivid, specific details and comparisons, provides a fuller impression and engages the reader’s interest and imagination. In descriptive or narrative paragraphs, supporting sentences present details and actions in vivid, specific language in objective or subjective ways, appealing to the readers’ senses to make them see and experience the subject. In addition, some sentences writers use make comparisons that bring together or substitute the familiar with the unfamiliar, thus enhancing and adding depth to the description of the incident, place, person, or idea.

In a persuasive essay about raising the wage for certified nursing assistants, a paragraph might focus on the expectations and duties of the job, comparing them to that of a registered nurse. Needless to say, a few sentences that simply list the certified nurse’s duties will not give readers a complete enough idea of what these healthcare professionals do. If readers do not have plenty of information about the duties and the writer’s experience in performing them for what she considers inadequate pay, the paragraph fails to do its part in convincing readers that the pay is inadequate and should be increased.

In informative or persuasive writing, a supporting sentence usually offers one of the following:

- Reason: The refusal of the baby boom generation to retire is contributing to the current lack of available jobs.

- Fact: Many families now rely on older relatives to support them financially.

- Statistic: Nearly 10 percent of adults are currently unemployed in the United States.

- Quotation: “We will not allow this situation to continue,” stated Senator Johns.

- Example: Last year, Bill was asked to retire at the age of fifty-five.

The type of supporting sentence you choose will depend on what you are writing and why you are writing. For example, if you are attempting to persuade your audience to take a particular position, you should rely on facts, statistics, and concrete examples, rather than personal opinions. Personal testimony in the form of an extended example can be used in conjunction with the other types of support.

Consider the elements in the following paragraph.

Example Persuasive Paragraph

Topic sentence: There are numerous advantages to owning a hybrid car.

Sentence 1 (statistic): First, they get 20 percent to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel- efficient gas-powered vehicle.

Sentence 2 (fact): Second, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving.

Sentence 3 (reason): Because they do not require as much gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump.

Sentence 4 (example): Alex bought a hybrid car two years ago and has been extremely impressed with its performance.

Sentence 5 (quotation): “It’s the cheapest car I’ve ever had,” she said. “The running costs are far lower than previous gas powered vehicles I’ve owned.”

Concluding sentence: Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Sometimes the writing situation does not allow for research to add specific facts or other supporting information, but paragraphs can be developed easily with examples from the writer’s own experience.

Farheya, a student in a freshman English Composition class, quickly drafted an essay during a timed writing assignment in class. To practice improving paragraph development, she selected the body paragraph below to add support:

Example of Original Body Paragraph

Topic: Should parents prevent their children from watching television? Discuss.

Preventing children from watching television is a way for parents to preserve their children’s innocence and keep exposure towards anything inappropriate at bay. From simply seeing movies and television when I was younger, I saw things I shouldn’t have, no matter how fast I switched the channel. Television shows and movies not only display physical indecency, but also verbal. Movies on TV sometimes do voice-overs of profane words, but they also leave a few words uncensored. The ease of flipping through channels on cable or choosing a show on a streaming service based on misleading descriptors or images, makes TV potentially toxic for the minds of children, and if parents prevented TV in general, they wouldn’t have to worry about what their children may accidentally see or hear.

The original paragraph identifies two categories of indecent material, and there is mention of profanity to provide a clue as to what the student thinks is indecent. However, the paragraph could use some examples to make the idea of inappropriate material clearer. Farheya considered some of the television shows she had seen and made a few changes.

Example of Revised Body Paragraph

Preventing children from watching television is a way for parents to preserve their children’s innocence and keep exposure towards anything inappropriate at bay. From simply seeing movies and television when I was younger, I saw things I shouldn’t have, no matter how fast I switched the channel. For instance, Game of Thrones quickly became known for its graphic violence and sexuality, but the widespread viewership of the series made it pervasively part of popular culture. Fans of other fantasy media, such as Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, were pulled into the cinematography and world-building, and as it was “fantasy,” parents may not have realized the inappropriateness of the contents and let their children watch it, especially if the children were fans of fantasy and the parents were not interested in the genre. Television shows not only display physical indecency, but also verbal. Many television shows have no filters, and the characters say profane words freely. South Park, as a cartoon, seems as if it may be relatively safe to pass by and may be mostly relatively visually innocent, but the continual profanity, frequent discussions implying the fourth-grade main characters are sexually active, and the demeaning language concerning a wide range of people and groups. Though the show started in 1997, it is still running today and original episodes and re-runs make it a frequent encounter on cable tv as well as various streaming services at different times. The ease of flipping through channels on cable or choosing a show on a streaming service based on misleading descriptors or images, makes TV potentially toxic for the minds of children, and if parents prevented TV in general, they wouldn’t have to worry about what their children may accidentally see or hear.

Farheya’s addition of a few examples helps to convey why she thinks she would be better off without a television. Depending on the context of the paragraph and its centrality to a larger argument, she could even add more specifics for further persuasive evidence. She might decide to add specific descriptions of scenes (such as a description of the violence or sexual content in Game of Thrones) or quotations (demonstrating the discussed profanity or sexual content in South Park) from the relevant shows.

Concluding Sentences

An effective concluding sentence draws together all the ideas raised in your paragraph. It reminds readers of the main point—the topic sentence—without restating it in exactly the same words. Using the hamburger example, the top bun (the topic sentence) and the bottom bun (the concluding sentence) are very similar. They frame the “meat” or body of the paragraph.

Compare the topic sentence and concluding sentence from the first example on hybrid cars:

Topic Sentence: There are many advantages to owning a hybrid car.

Concluding Sentence: Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Notice the use of the synonyms advantages and benefits. The concluding sentence reiterates the idea that owning a hybrid is advantageous without using the exact same words. It also summarizes two examples of the advantages covered in the supporting sentences: low running costs and environmental benefits.

Writers should avoid introducing any new ideas into a concluding sentence because a conclusion is intended to provide the reader with a sense of completion. Introducing a subject that is not covered in the paragraph will confuse readers and weaken the writing.

A concluding sentence may do any of the following:

- Restate the main idea.

Example

Childhood obesity is a growing problem in the United States.

- Summarize the key points in the paragraph

Example

A lack of healthy choices, poor parenting, and an addiction to video games are among the many factors contributing to childhood obesity.

- Draw a conclusion based on the information in the paragraph.

Example

These statistics indicate that unless we take action, childhood obesity rates will continue to rise.

- Make a prediction, suggestion, or recommendation about the information in the paragraph.

Example

Based on this research, more than 60 percent of children in the United States will be morbidly obese by the year 2030 unless we take evasive action.

- Offer an additional observation about the controlling idea.

Example

Childhood obesity is an entirely preventable tragedy.

Paragraph Length

Although paragraph length is discussed in the section on developing paragraphs with supporting sentences, some additional reminders about when to start a new paragraph may prove helpful to writers:

- If a paragraph is over a page long, consider providing a paragraph break for readers. Look for a logical place to divide the paragraph; then revise the opening sentence of the second paragraph to maintain coherence.

- A series of short paragraphs can be confusing and choppy. Examine the content of the paragraphs and combine ones with related ideas or develop each one further.

- When dialogue is used, begin a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

- Begin a new paragraph to indicate a shift in subject, tone, or time and place.

Improving Paragraph Coherence

A strong paragraph holds together well, flowing seamlessly from the topic sentence into the supporting sentences and on to the concluding sentence. To help organize a paragraph and ensure that ideas logically connect to one another, writers use a combination of elements:

- A clear organizational pattern: chronological (for narrative writing and describing processes), spatial (for descriptions of people or places), order of importance, general to specific (deductive), specific to general (inductive)

- Transitional words and phrases: These connecting words describe a relationship between ideas.

- Repetition of ideas: This element helps keep the parts of the paragraph together by maintaining focus on the main idea, so this element reinforces both paragraph coherence and unity.

In the following example, notice the use of transitions (bolded) and key words (underlined):

Example of Transition Words

Owning a hybrid car benefits both the owner and the environment. First, these cars get 20 percent to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient gas-powered vehicle. Second, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. Alex bought a hybrid car two years ago and has been extremely impressed with its performance. “It’s the cheapest car I’ve ever had,” she said. “The running costs are far lower than previous gas-powered vehicles I’ve owned.” Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Words such as first and second are transition words that show sequence or clarify order. They help organize the writer’s ideas by showing that he or she has another point to make in support of the topic sentence. The transition word because is a transition word of consequence that continues a line of thought. It indicates that the writer will provide an explanation of a result. In this sentence, the writer explains why hybrid cars will reduce dependency on fossil fuels (because they do not require gas).

In addition to transition words, the writer repeats the word hybrid (and other references such as these cars, and they), and ideas related to benefits to keep the paragraph focused on the topic and hold it together.

To include a summarizing transition for the concluding sentence, the writer could rewrite the final sentence as follows:

In conclusion, given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.