Argument

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Identify the elements of an argumentative essay

- Create the structure of an argumentative essay

- Develop an argumentative essay

What Is Argumentation?

Arguments are everywhere, and practically everything is or has been debated at some time. Your ability to develop a point of view on a topic and provide evidence is the process known as Argumentation. Argumentation asserts the reasonableness of a debatable position, belief, or conclusion. This process teaches us how to evaluate conflicting claims and judge evidence and methods of investigation while helping us to clarify our thoughts and articulate them accurately. Arguments also consider the ideas of others in a respectful and critical manner. In argumentative writing, you are typically asked to take a position on an issue or topic and explain and support your position. The purpose of the argument essay is to establish the writer’s opinion or position on a topic and persuade others to share or at least acknowledge the validity of your opinion.

Structure of the Argumentative Essay

An effective argumentative essay introduces a compelling, debatable topic to engage the reader. In an effort to persuade others to share your opinion, the writer should explain and consider all sides of an issue fairly and address counterarguments or opposing perspectives. The following five features make up the structure of an argumentative essay:

Introduction

The argumentative essay begins with an introduction that provides appropriate background to inform the reader about the topic. Your introduction may start with a quote, a personal story, a surprising statistic, or an interesting question. This strategy engages the reader’s attention while introducing the topic of the essay. The background information is a short description of your topic. In this section, you should include any information that your reader needs to understand your topic.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is one sentence in your introductory paragraph that concisely summarizes your main point(s) and claim(s) and presents your position on the topic. The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on.

Body Paragraphs and Supporting Details

Your argument must use an organizational structure that is logical and persuasive. There are three types of argumentative essays, each with differing organizational structures: Classical, Toulmin, and Rogerian.

Organization of the Classical Argument

The Classical Argument was developed by a Greek philosopher, Aristotle. It is the most common. The goal of this model is to convince the reader about a particular point of view. The Classical Argument relies on appeals to persuade an audience specifically: ethos (ethical appeal) is an appeal to the writer’s creditability, logos (logical appeal) is an appeal based on logic, and pathos (pathetic appeal) is an appeal based on emotions. The structure of the classical model is as follows:

- Introductory paragraph includes the thesis statement

- Background on the topic provides information to the reader about the topic

- Supporting evidence integrates appeals

- Counterargument and rebuttal address major opposition

- Conclusion restates the thesis statement

Organization of the Toulmin Argument

The Toulmin Argument was developed by Stephen Toulmin. The Toulmin method works well when there are no clear truths or solutions to a problem. It considers the complex nature of most situations. There are six basic components:

- Introduction—thesis statement or the main claim (statement of opinion)

- Grounds—the facts, data, or reasoning on which the claim is based

- Warrant—logic and reasoning that connect the ground to the claim

- Backing—additional support for the claim that addresses different questions related to the claim

- Qualifier—expressed limits to the claim stating the claim may not be true in all situations

- Rebuttal—counterargument against the claim

Organization of the Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian Argument was developed by Carl Rogers. Rogerian argument is a negotiating strategy in which common goals are identified and opposing views are described as objectively as possible in an effort to establish common ground and reach an agreement. Whereas the traditional argument focuses on winning, the Rogerian model seeks a mutually satisfactory solution. This argument considers different standpoints and works on collaboration and cooperation. Following is the structure of the Rogerian model:

- Introduction and Thesis Statement—presents the topic as a problem to solve together, rather than an issue

- Opposing Position—expressed acknowledgment of counterargument that is fair and accurate

- Statement of Claim—writer’s perspective

- Middle Ground—discussion of a compromised solution

- Conclusion—remarks stating the benefits of a compromised solution

The Following Words and Phrases: Writing an Argument

Using transition words or phrases at the beginning of new paragraphs or within paragraphs helps a reader to follow your writing. Transitions show the reader when you are moving on to a different idea or further developing the same idea. Transitions create a flow, or connection, among all sentences, and that leads to coherence in your writing. The following words and phrases will assist in linking ideas, moving your essay forward, and improving readability:

- Also, in the same way, just as, likewise, similarly

- But, however, in spite of, on the one hand, on the other hand, nevertheless, nonetheless, notwithstanding, in contrast, on the contrary, still yet

- First, second, third…, next, then, finally

- After, afterward, at last, before, currently, during, earlier, immediately, later, meanwhile, now, recently, simultaneously, subsequently, then

- For example, for instance, namely, specifically, to illustrate

- Even, indeed, in fact, of course, truly, without question, clearly

- Above, adjacent, below, beyond, here, in front, in back, nearby, there

- Accordingly, consequently, hence, so, therefore, thus

- Additionally, again, also, and, as well, besides, equally important, further, furthermore, in addition, moreover, then

- Finally, in a word, in brief, briefly, in conclusion, in the end, in the final analysis, on the whole, thus, to conclude, to summarize, in sum, to sum up, in summary

Professional Writing Example

The following essay, “Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States,” by Scott McLean is an argumentative essay. As you read the essay, determine the author’s major claim and major supporting examples that support his claim.

Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States

By Scott McLean

The United States is the only modernized Western nation that does not offer publicly funded health care to all its citizens; the costs of health care for the uninsured in the United States are prohibitive, and the practices of insurance companies are often more interested in profit margins than providing health care. These conditions are incompatible with US ideals and standards, and it is time for the US government to provide universal health care coverage for all its citizens. Like education, health care should be considered a fundamental right of all US citizens, not simply a privilege for the upper and middle classes.

One of the most common arguments against providing universal health care coverage (UHC) is that it will cost too much money. In other words, UHC would raise taxes too much. While providing health care for all US citizens would cost a lot of money for every tax-paying citizen, citizens need to examine exactly how much money it would cost, and more important, how much money is “too much” when it comes to opening up health care for all. Those who have health insurance already pay too much money, and those without coverage are charged unfathomable amounts. The cost of publicly funded health care versus the cost of current insurance premiums is unclear. In fact, some Americans, especially those in lower income brackets, could stand to pay less than their current premiums.

However, even if UHC would cost Americans a bit more money each year, we ought to reflect on what type of country we would like to live in, and what types of morals we represent if we are more willing to deny health care to others on the basis of saving a couple hundred dollars per year. In a system that privileges capitalism and rugged individualism, little room remains for compassion and love. It is time that Americans realize the amorality of US hospitals forced to turn away the sick and poor. UHC is a health care system that aligns more closely with the core values that so many Americans espouse and respect, and it is time to realize its potential.

Another common argument against UHC in the United States is that other comparable national health care systems, like that of England, France, or Canada, are bankrupt or rife with problems. UHC opponents claim that sick patients in these countries often wait in long lines or long wait lists for basic health care. Opponents also commonly accuse these systems of being unable to pay for themselves, racking up huge deficits year after year. A fair amount of truth lies in these claims, but Americans must remember to put those problems in context with the problems of the current US system as well. It is true that people often wait to see a doctor in countries with UHC, but we in the United States wait as well, and we often schedule appointments weeks in advance, only to have onerous waits in the doctor’s “waiting rooms.”

Critical and urgent care abroad is always treated urgently, much the same as it is treated in the United States. The main difference there, however, is cost. Even health insurance policy holders are not safe from the costs of health care in the United States. Each day an American acquires a form of cancer, and the only effective treatment might be considered “experimental” by an insurance company and thus is not covered. Without medical coverage, the patient must pay for the treatment out of pocket. But these costs may be so prohibitive that the patient will either opt for a less effective, but covered, treatment; opt for no treatment at all; or attempt to pay the costs of treatment and experience unimaginable financial consequences. Medical bills in these cases can easily rise into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is enough to force even wealthy families out of their homes and into perpetual debt. Even though each American could someday face this unfortunate situation, many still choose to take the financial risk. Instead of gambling with health and financial welfare, US citizens should press their representatives to set up UHC, where their coverage will be guaranteed and affordable.

Despite the opponents’ claims against UHC, a universal system will save lives and encourage the health of all Americans. Why has public education been so easily accepted, but not public health care? It is time for Americans to start thinking socially about health in the same ways they think about education and police services: as rights of US citizens.

Discussion Questions

- What is the author’s main claim in this essay?

- Does the author fairly and accurately present counterarguments to this claim? Explain your answer using evidence from the essay.

- Does the author provide sufficient background information for his reader about this topic? Point out at least one example in the text where the author provides background on the topic. Is it enough?

- Does the author provide a course of action in his argument? Explain your response using specific details from the essay.

Student Writing Example

Salvaging Our Old-Growth Forests

It’s been so long since I’ve been there I can’t clearly remember what it’s like. I can only look at the pictures in my family photo album. I found the pictures of me when I was a little girl standing in front of a towering tree with what seems like endless miles and miles of forest in the background. My mom is standing on one side of me holding my hand, and my older brother is standing on the other side of me, making a strange face. The faded pictures don’t do justice to the real-life magnificence of the forest in which they were taken—the Olympic National Forest—but they capture the awe my parents felt when they took their children to the ancient forest.

Today these forests are threatened by the timber companies that want state and federal governments to open protected old-growth forests to commercial logging. The timber industry’s lobbying attempts must be rejected because the logging of old-growth forests is unnecessary, because it will destroy a delicate and valuable ecosystem, and because these rare forests are a sacred trust.

Those who promote logging of old-growth forests offer several reasons, but when closely examined, none is substantial. First, forest industry spokesmen tell us the forest will regenerate after logging is finished. This argument is flawed. In reality, the logging industry clear-cuts forests on a 50-80 year cycle, so that the ecosystem being destroyed—one built up over more than 250 years—will never be replaced. At most, the replanted trees will reach only one-third the age of the original trees. Because the same ecosystem cannot rebuild if the trees do not develop full maturity, the plants and animals that depend on the complex ecosystem—with its incredibly tall canopies and trees of all sizes and ages—cannot survive. The forest industry brags about replaceable trees but doesn’t mention a thing about the irreplaceable ecosystems.

Another argument used by the timber industry, as forestry engineer D. Alan Rockwood has said in a personal correspondence, is that “an old-growth forest is basically a forest in decline….The biomass is decomposing at a higher rate than tree growth.” According to Rockwood, preserving old-growth forests is “wasting a resource” since the land should be used to grow trees rather than let the old ones slowly rot away, especially when harvesting the trees before they rot would provide valuable lumber. But the timber industry looks only at the trees, not at the incredibly diverse bio-system which the ancient trees create and nourish. The mixture of young and old-growth trees creates a unique habitat that logging would destroy.

Perhaps the main argument used by the logging industry is economic. Using the plight of loggers to their own advantage, the industry claims that logging old-growth forests will provide jobs. They make all of us feel sorry for the loggers by giving us an image of a hardworking man put out of work and unable to support his family. They make us imagine the sad eyes of the logger’s children. We think, “How’s he going to pay the electricity bill? How’s he going to pay the mortgage? Will his family become homeless?” We all see these images in our minds and want to give the logger his job so his family won’t suffer. But in reality giving him his job back is only a temporary solution to a long-term problem. Logging in the old-growth forest couldn’t possibly give the logger his job for long. For example, according to Peter Morrison of the Wilderness Society, all the old-growth forests in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest would be gone in three years if it were opened to logging (vi). What will the loggers do then? Loggers need to worry about finding new jobs now and not wait until there are no old-growth trees left.

Having looked at the views of those who favor logging of old-growth forests, let’s turn to the arguments for preserving all old growth. Three main reasons can be cited.

First, it is simply unnecessary to log these forests to supply the world’s lumber. According to environmentalist Mark Sagoff, we have plenty of new-growth forests from which timber can be taken (89-90). Recently, there have been major reforestation efforts all over the United States, and it is common practice now for loggers to replant every tree that is harvested. These new-growth forests, combined with extensive planting of tree farms, provide more than enough wood for the world’s needs. According to forestry expert Robert Sedjo (qtd. in Sagoff 90), tree farms alone can supply the world’s demand for industrial lumber. Although tree farms are ugly and possess little diversity in their ecology, expanding tree farms is far preferable to destroying old-growth forests.

Moreover, we can reduce the demand for lumber. Recycling, for example, can cut down on the use of trees for paper products. Another way to reduce the amount of trees used for paper is with a promising new innovation, kenaf, a fast-growing, 15-foot-tall, annual herb that is native to Africa. According to Jack Page in Plant Earth, Forest, kenaf has long been used to make rope, and it has been found to work just as well for paper pulp (158).

Another reason to protect old-growth forests is the value of their complex and very delicate ecosystem. The threat of logging to the northern spotted owl is well known. Although loggers say “people before owls,” ecologists consider the owls to be warnings, like canaries in mine shafts that signal the health of the whole ecosystem. Evidence provided by the World Resource Institute shows that continuing logging will endanger other species. Also, Dr. David Brubaker, an environmentalist biologist at Seattle University, has said in a personal interview that the long-term effects of logging will be severe. Loss of the spotted owl, for example, may affect the small rodent population, which at the moment is kept in check by the predator owl. Dr. Brubaker also explained that the old-growth forests also connect to salmon runs. When dead timber falls into the streams, it creates a habitat conducive to spawning. If the dead logs are removed, the habitat is destroyed. These are only two examples in a long list of animals that would be harmed by logging of old-growth forests.

Finally, it is wrong to log in old-growth forests because of their sacred beauty. When you walk in an old-growth forest, you are touched by a feeling that ordinary forests can’t evoke. As you look up to the sky, all you see is branch after branch in a canopy of towering trees. Each of these amazingly tall trees feels inhabited by a spirit; it has its own personality. “For spiritual bliss take a few moments and sit quietly in the Grove of the patriarchs near Mount Rainier or the redwood forests of Northern California,” said Richard Linder, environmental activist and member of the National Wildlife Federation. “Sit silently,” he said, “and look at the giant living organisms you’re surrounded by; you can feel the history of your own species.” Although Linder is obviously biased in favor of preserving the forests, the spiritual awe he feels for ancient trees is shared by millions of other people who recognize that we destroy something of the world’s spirit when we destroy ancient trees, or great whales, or native runs of salmon. According to Al Gore, “We have become so successful at controlling nature that we have lost our connection to it” (qtd. in Sagoff 96). We need to find that connection again, and one place we can find it is in the old-growth forests.

The old-growth forests are part of the web of life. If we cut this delicate strand of the web, we may end up destroying the whole. Once the old trees are gone, they are gone forever. Even if foresters replanted every tree and waited 250 years for the trees to grow to ancient size, the genetic pool would be lost. We’d have a 250-year-old tree farm, not an old-growth forest. If we want to maintain a healthy earth, we must respect the beauty and sacredness of the old-growth forests.

Works Cited

Brubaker, David. Personal interview. 25 Sept. 1998.

Linder, Richard. Personal interview. 12 Sept. 1998.

Morrison, Peter. Old Growth in the Pacific Northwest: A Status Report. Alexandria: Global Printing, 1988.

Page, Jack. Planet Earth, Forest. Alexandria: Time-Life, 1983.

Rockwood, D. Alan. Email to the author. 24 Sept. 1998.

Sagoff, Mark. “Do We Consume Too Much?” Atlantic Monthly June 1997: 80-96.

World Resource Institute. “Old Growth Forests in the United States Pacific Northwest.” 13 Sept. 1998 http://www.wri.org/biodiv.

Discussion Questions

- What is the author’s main claim in this essay?

- Does the author fairly and accurately present counterarguments to this claim? Explain your answer and describe an example of counterargument in the essay.

- Does the author provide sufficient background information for his reader about this topic? Point out at least one example in the text where the author provides background on the topic. Is it enough?

- Does the author provide a course of action in his argument? Explain your response using specific details from the essay.

Your Turn

What societal or personal experiences have you observed and considered to be argumentative?

What organizational structure would be best for the topic you consider: Classical, Toulmin, or Rogerian?

Key Terms

- Appeals

- Ethos

- Pathos

- Logos

- Warrant

- Qualifier

- Counterargument

- Grounds

- Classical method

- Toulmin method

- Rogerian method

- Middle Ground

- Argumentation

Summary

In argumentative writing, you are typically asked to take a position on an issue or topic and explain and support your position with research from reliable and credible sources. Argumentation can be used to convince readers to accept or acknowledge the validity of your position or to question or refute a position you consider to be untrue or misguided.

- The purpose of argument in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style are appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions

[h5p id=”8″]

[h5p id=”9″]

Reflective Response

Reflect on your writing process for the argumentative essay. What was the most challenging? What was the easiest? Did your position on the topic change as a result of reviewing and evaluating new knowledge or ideas about the topic?

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

Discusses fact-checking; YouTube video discussing Stanford study of fact-checkers

Introduction

When you find a source of information, how do you know if it’s true? How can you be sure that it is a reliable, trustworthy, and effective piece of evidence for your research? This chapter will introduce you to a set of strategies to quickly and effectively verify your sources, based on the approach taken by professional fact-checkers. Fact-checking is a form of information hygiene—it can minimize your own susceptibility to misinformation and disinformation, and help you to avoid spreading it to others.

As an introduction, please watch the following video [3:13], which discusses the results of a very interesting study of Stanford students, historians, and professional fact-checkers (Wineburg and McGrew). Which group do you think did the best job of identifying reliable sources?

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Sources

"Online Verification Skills - Video 1: Introductory Video." YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

Wineburg, Sam, and Sarah McGrew. “Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information.” Stanford History Education Group Working Paper No. 2017-A1, 6 Oct. 2017, dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3048994.

Introduction

When you find a source of information, how do you know if it’s true? How can you be sure that it is a reliable, trustworthy, and effective piece of evidence for your research? This chapter will introduce you to a set of strategies to quickly and effectively verify your sources, based on the approach taken by professional fact-checkers. Fact-checking is a form of information hygiene—it can minimize your own susceptibility to misinformation and disinformation, and help you to avoid spreading it to others.

As an introduction, please watch the following video [3:13], which discusses the results of a very interesting study of Stanford students, historians, and professional fact-checkers (Wineburg and McGrew). Which group do you think did the best job of identifying reliable sources?

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Sources

"Online Verification Skills - Video 1: Introductory Video." YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

Wineburg, Sam, and Sarah McGrew. “Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information.” Stanford History Education Group Working Paper No. 2017-A1, 6 Oct. 2017, dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3048994.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

Avoiding the thesis first model

Emily Wierszewski [Adapted by Liz Delf, Rob Drummond, and Kristy Kelly]

Our collective belief in the importance of definite answers impacts many areas of our lives, including how we understand the process and purpose of research. Specifically, it leads to a thesis-first research model in which research is only used to verify our existing ideas or theses. In this model, there is no room for doubt or ambiguity. We assume we need to know the answers to our problems or questions before the process gets underway before we consult and evaluate what others have said.

Research can be productively used in this way to verify assumptions and arguments. Sometimes what we need is just a little support for an idea, a confirmation of the best approach to a problem, or the answer to simple questions. For example, we might believe the new iPhone is the best smartphone on the market and use research on the phone’s specs to prove we’re right. This kind of thesis-first approach to research becomes harmful, however, when we assume that it is the only or the most valuable way to conduct research.

Evidence of this widespread assumption is easy to find. A simple search for the research process on Google will yield multiple hits hosted by academic institutions that suggest a researcher needs a thesis early in the research process. For instance, the University of Maryland University College’s Online Guide to Writing and Research suggests that a thesis should be developed as soon as source collection gets underway, though that thesis may change over time. This strategy is endorsed by multiple research library websites, such as the University of Minnesota.

And yet genuine inquiry—the kind of research that often leads to new ideas and important choices—tends to begin with unsettled problems and questions rather than with thesis statements and predetermined answers. Wernher von Braun, an engineer whose inventions advanced the US space program in the mid-twenty-first century, famously describes research as “What I’m doing when I don’t know what I’m doing” (qtd. in Pfeiffer 238).

The understanding of research as discovery is echoed in the recent “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education,” a document authored by the Association of College and Research Librarians (ACRL). They write that research often begins with open-ended questions that are “based on information gaps or reexamination of existing, possibly conflicting, information” (7). In other words, research isn’t just for backing up our hunches. It can, and should, also be used as a method of investigating areas of uncertainty, curiosity, conflict, and multiple perspectives.

As the ACRL’s framework also emphasizes, when researchers review published source material around their topic, points of disagreement will be discovered; these points are expected as scholars propose ideas to address complicated issues. When we are open to selecting and engaging with these multiple published perspectives in our research, we’re also forced to consider how they extend or challenge our beliefs and ideas about a topic. Considering all sides, we can then make a more informed decision about our questions or topics.

Another potential harm of the thesis-first model of research is the attendant assumption that the research process is linear. In a thesis-guided research process, a question is posed, an answer is generated, and sources are found that match up with that answer. Truthfully, research rarely progresses on an uncluttered path toward a clear solution. Instead, research is a recursive process that involves many diversions, bumps, and missteps.

Research is sometimes described as cyclical and fluid. As we research, we may find ourselves returning to and changing our question, or we may near the end of a project and think we’re done but discover we need to go back to find more or better sources. The messiness of research requires us to be flexible, often modifying our approaches along the way. When we enter the research process with a narrow and rigid focus on our thesis, we can become discouraged and inclined to abandon our ideas when the research process does not unfold neatly.

In place of a thesis-first model, we would be better served to begin research with a question or a statement of a problem. We should conduct research not just to back up our preexisting assumptions and prove we’re right about something but also when we feel curious or confused and do not have answers. Why is something the way it is? Why doesn’t the data quite add up? How could something be changed for the better?

When we understand research as a process of discovery rather than a process of proof, we open ourselves up to be changed by our research—to better our lives, our decisions, and our world. We acknowledge that we do not have the only or the best answer to every question and that we might learn something from considering the ideas of others. While research definitely has the power to impact our lives and beliefs, research doesn’t always have to be life altering. But in a thesis-first model where our only goal is just to prove we’re right, there is no possibility of being changed by our research.

Here’s a practical example of the difference. Just imagine the results of a research process beginning with a thesis like “Human trafficking should have harsher legal penalties” versus one that starts with an open-ended question like “Why does human trafficking persist in the democratic nation of the United States?” In the thesis-first model, a researcher would likely only encounter sources that argue for their preexisting belief: that harsher penalties are needed. They would probably never be exposed to multiple perspectives on this complex issue, and the result would just be confirmation of their earlier beliefs.

However, a researcher who begins with an open-ended question motivated by curiosity, whose goal is not to prove anything but to discover salient ideas about a human rights issue, has the chance to explore different thoughts about human trafficking and come to her own conclusions as she researches why it’s a problem and what ought to be done to stop it, not just create stronger consequences for it.

Viewing research as a process of discovery allows us to accept that not every question is answerable and that questions sometimes lead only to more questions. For instance, the researcher in the previous paragraph exploring the issue of human trafficking might find that there is no clear, single explanation for the prevalence of this human rights violation and that she’s interested to know more about the role of immigration laws and human trafficking—something she never even thought of before she did her research.

When researchers do discover answers, they may find those answers are fluid and debatable. What we have at any time is only a consensus between informed parties, and at any time, new research or insights can cause that agreement to shift. As we read in chapter 17, the philosopher and literary critic Kenneth Burke (1897–1993) explains the constructed nature of knowledge as an unending conversation. According to Burke, the moment in which a researcher reads and participates in scholarship around the research topic or problem is just a speck on a continuum of conversation that has been ongoing well before the researcher thought of the question and will continue long after the researcher has walked away from it. As Burke writes, “The discussion is interminable” (110).

So how can we move toward embracing uncertainty? In his book A More Beautiful Question, Warren Berger suggests that parents and those who work with young children can foster curiosity by welcoming questions. Parents also need to learn to be comfortable with saying “I don’t know” in response rather than searching for a simple answer. Berger also recommends that as children go through school, parents and educators can work together to support children’s questioning nature rather than always privileging definite answers. When students graduate and move into the working world, employers can encourage them to ask questions about policies, practices, and workplace content; employees should be given the freedom to explore those questions with research, which can potentially lead to more sustainable and current policies, practices, and content. The same goes for civic and community life, where any form of questioning or inquiry is often misconstrued as a challenge to authority. To value questions more than answers in our personal and professional lives requires a cultural shift.

Although our culture would tell us that we have to know everything and that we should even begin a research project by knowing the answer to our question, there is obvious value in using research as a tool to engage our curiosity and sense of wonder as human beings—perhaps even to improve our lives or the lives of others. If all researchers started the process with preconceived answers, no new findings would ever come to be. In order to truly learn about a topic or issue, especially when it involves important decision-making, we need to learn to embrace uncertainty and feel comfortable knowing we might not always have an answer when we begin a research project.

The original chapter, Research Starts with a Thesis Statement by Emily A. Wierszewski, is from Bad Ideas about Writing

Discussion Questions

- Describe your typical research process for previous classes or papers. Was this thesis-first or inquiry-based research? What were the benefits or drawbacks of this approach? What led you to that method?

- Imagine you had all the time in the world to research a topic that you were personally passionate about. How might your approach to research be different than in a class?

- What does Werner von Braun mean when he says that research is “what I’m doing when I don’t know what I’m doing”? Have you experienced this version of research, either in writing a paper or in another context?

Activities

- Go down a “rabbit hole” with your research. Use your curiosity to guide you in this inquiry-based research activity.

- Start at a Wikipedia page related to your topic. (If you don’t have a topic, try “organic farming,” “Israel,” “CRISPR,” “American Sign Language,” or something else.)

- Read the page, but follow your interest, and click through to other pages as you go. Spend ten to fifteen minutes following your interest from one topic to the next. Sometimes you might backtrack or search other terms—that’s OK too.

- Reflect on the process. Where did you start? Where did you end up? How did you feel as you were reading, and how did it compare with your typical research experience for a class project? What did this process suggest about inquiry-based learning?

- Individually or as a class, brainstorm potential research questions for a topic of your choice. Discuss the range of options you came up with. How did this approach lead you in new directions?

Additional Resources

- For additional information about the power and purpose of inquiry in our everyday lives, consult Warren Berger’s book A More Beautiful Question (Bloomsbury), which provides an overview of how to engage in authentic inquiry in a variety of settings. Berger offers practical advice for learning to develop research questions that are driven by discovery and innovation. Robert Davis and Mark Shadle also provide a defense of inquiry in their article “‘Building a Mystery’: Alternative Research Writing and the Academic Art of Seeking” (College Composition and Communication).

- For more specific information about all of the stages of the research process, including formulating a question, Bruce Ballenger’s classic guide to research, The Curious Researcher (Longman), and Ken Macrorie’s canonical text I Search (Boynton/Cook), which focuses on research with personal value, may be useful. Clark College Libraries’ website also provides a quick reference chart outlining the research process entitled “The Research Process Daisy.”

- Wendy Bishop and Pavel Zemliansky’s edited collection, The Subject Is Research: Processes and Practices (Boynton/Cook), provides perspectives from multiple authors about various research techniques such as interviewing and observation that can be used to engage in the inquiry process.

Works Cited

ACRL Board. “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), 16 Feb. 2022, www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

Berger, Warren. A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. Bloomsbury, 2014.

Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action. 3rd ed., U of California P, 1973.

Pfeiffer, John. “The Basic Need for Basic Research.” New York Times Magazine, 24 Nov. 1957. 238.

“Writing: Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea.” Online Guide to Writing and Research, U of Maryland Global Campus, www.umgc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/online-guide-to-writing/tutorial/chapter2/ch2-10.html.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

How to use Wikipedia wisely

"To tell students not to use Wikipedia is to deprive them of one of the most useful tools on the Internet. Instead of teaching them to avoid it, we should be teaching students how to use Wikipedia wisely" ("How to Use Wikipedia Wisely").

Misconceptions & Benefits

Wikipedia—the world's largest reference website—is broadly misunderstood. Because it is written by thousands of anonymous volunteers around the world, Wikipedia generates uncertainty or skepticism in many. If just anyone can change Wikipedia, won’t there be inaccuracies? Won’t people potentially abuse that power?

The open, collaborative approach of Wikipedia means that it is susceptible to vandalism, unverified information, or subtle viewpoint promotion. However, that same open approach also increases the chances that factual errors and misleading statements will be quickly corrected, and that articles will be consistently improved and updated. Indeed, an often-cited 2005 study (Giles), as well as a follow-up study in 2012 (Casebourne et al.), found no significant differences in accuracy between Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica articles.

![]()

Additionally, the Wikipedia community has strict rules about providing citations or references for facts and claims, and authors must adopt a neutral point of view. Because of this, Wikipedia articles are often the best available introduction to a subject. If you are researching a complex question, starting with the resources and summaries provided by Wikipedia can give you a substantial running start on an issue. For more information about this, see the section on Background Reading. The requirement for Wikipedia authors to cite their sources has another beneficial effect. If you can find a claim expressed in a Wikipedia article, you can almost always follow the footnotes to reliable sources for further research and evidence.

Areas for Caution

Not all Wikipedia articles are useful. Some articles are incomplete or contain "citation needed" warnings. You may find very short "stub" articles that are awaiting either further expansion, or deletion. You should avoid using these types of articles for your research.

Another known concern is systemic bias in Wikipedia, including gender and racial bias. For example, of the over 130,000 active editors of Wikipedia, only 8.5% to 16% are female; of the over 1.5 million biographies on Wikipedia, only 18% are about women (Kantor). Wikipedia has launched numerous initiatives to encourage more women to become editors and to improve their coverage of women; even so, the gender gap persists. With Wikipedia as well as other, more traditional forms of publishing, we must be aware of who creates the information we consume, and understand how that impacts our knowledge about research topics and the world around us. For more on bias, see the page on Information Sources: Bias.

Using Wikipedia Wisely

With an awareness of these benefits and concerns, you can more effectively use Wikipedia for fact-checking and to find background information on a topic. Please watch the following video [2:41] that addresses some of the common misconceptions about Wikipedia and demonstrates how you can use this tool wisely, as professional fact-checkers often do.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Sources

Casebourne, Imogen, et al. "Assessing the Accuracy and Quality of Wikipedia Entries Compared to Popular Online Encyclopaedias: A Comparative Preliminary Study Across Disciplines in English, Spanish and Arabic." Wikimedia, Epic and Univ. of Oxford, 2012. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Giles, Jim. "Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head." Nature, vol. 438, 2005, pp. 900–901, doi.org/10.1038/438900a.

“How to Use Wikipedia Wisely.” YouTube, uploaded by Stanford History Education Group, 23 Jan. 2020.

Image: “Run” by Alex Podolsky, adapted by Aloha Sargent, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Kantor, Jessica. "Wikipedia Still Hasn't Fixed Its Colossal Gender Gap." Fast Company, 13 Nov. 2019.

Misconceptions and Benefits section adapted from “Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and "Teaching with Wikipedia: A High Impact Open Educational Practice" by TJ Bliss, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

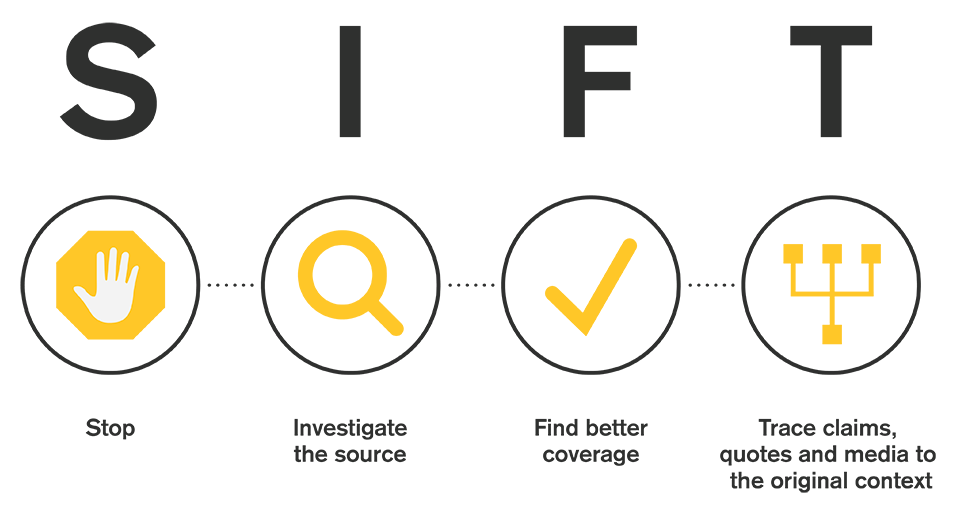

Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention. It is referred to as the "SIFT" method:

Stop

![]()

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don't, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you're looking at. In other words, don't read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us "engaged" with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging!

Investigate the Source

![]()

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you're reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you're watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn't mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can't ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating.

Please watch the following short video [2:44] for a demonstration of this strategy. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find Better Coverage

![]()

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there. Please watch this video [4:10] that demonstrates this strategy and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context

![]()

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. Please watch the following video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going "upstream" to find the original reporting source.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Sources

"Online Verification Skills - Video 2: Investigate the Source." YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

"Online Verification Skills - Video 3: Find the Original Source." YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

"Online Verification Skills - Video 4: Look for Trusted Work." YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

SIFT text adapted from “Check, Please! Starter Course,” licensed under CC BY 4.0

SIFT text and graphics adapted from “SIFT (The Four Moves)” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0