Basic Structure and Content of Argument

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Basics of an argument- claim, context, evidence, warrants, counterarguments

When you are tasked with crafting an argumentative essay, it is likely that you will be expected to craft your argument based upon a given number of sources–all of which should support your topic in some way. Your instructor might provide these sources for you, ask you to locate these sources, or provide you with some sources and ask you to find others. Whether or not you are asked to do additional research, an argumentative essay should contain the following basic components.

Claim: What Do You Want the Reader to Believe?

In an argument paper, the thesis is often called a claim. This claim is a statement in which you take a stand on a debatable issue. A strong, debatable claim has at least one valid counterargument, an opposite or alternative point of view that is as sensible as the position that you take in your claim. In your thesis statement, you should clearly and specifically state the position you will convince your audience to adopt. One way to accomplish this is via either a closed or open thesis statement.

A closed thesis statement includes sub-claims or reasons why you choose to support your claim.

Example of Closed Thesis Statement

The city of Houston has displayed a commitment to attracting new residents by making improvements to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

In this instance, walkability, city centers, and green spaces are the sub-claims, or reasons, why you would make the claim that Houston is attracting new residents.

An open thesis statement does not include sub-claims and might be more appropriate when your argument is less easy to prove with two or three easily-defined sub-claims.

Example of Open Thesis Statement

The city of Houston is a vibrant metropolis with a commitment to attracting new residents.

The choice between an open or a closed thesis statement often depends upon the complexity of your argument. Another possible construction would be to start with a research question and see where your sources take you.

A research question approach might ask a large question that will be narrowed down with further investigation.

Example of Research Question Approach

What has the city of Houston done to attract new residents and/or make the city more accessible?

As you research the question, you may find that your original premise is invalid or incomplete. The advantage to starting with a research question is that it allows for your writing to develop more organically according to the latest research. When in doubt about how to structure your thesis statement, seek the advice of your instructor or a writing center consultant.

A Note on Context: What Background Information About the Topic Does Your Audience Need?

Before you get into defending your claim, you will need to place your topic (and argument) into context by including relevant background material. Remember, your audience is relying on you for vital information such as definitions, historical placement, and controversial positions. This background material might appear in either your introductory paragraph(s) or your body paragraphs. How and where to incorporate background material depends a lot upon your topic, assignment, evidence, and audience. In most cases, kairos, or an opportune moment, factors heavily in the ways in which your argument may be received.

Evidence or Grounds: What Makes Your Reasoning Valid?

To validate the thinking that you put forward in your claim and sub-claims, you need to demonstrate that your reasoning is based on more than just your personal opinion. Evidence, sometimes referred to as grounds, can take the form of research studies or scholarship, expert opinions, personal examples, observations made by yourself or others, or specific instances that make your reasoning seem sound and believable. Evidence only works if it directly supports your reasoning — and sometimes you must explain how the evidence supports your reasoning (do not assume that a reader can see the connection between evidence and reason that you see).

Warrants: Why Should a Reader Accept Your Claim?

A warrant is the rationale the writer provides to show that the evidence properly supports the claim with each element working towards a similar goal. Think of warrants as the glue that holds an argument together and ensures that all pieces work together coherently.

An important way to ensure you are properly supplying warrants within your argument is to use topic sentences for each paragraph and linking sentences within that connect the particular claim directly back to the thesis. Ensuring that there are linking sentences in each paragraph will help to create consistency within your essay. Remember, the thesis statement is the driving force of organization in your essay, so each paragraph needs to have a specific purpose (topic sentence) in proving or explaining your thesis. Linking sentences complete this task within the body of each paragraph and create cohesion. These linking sentences will often appear after your textual evidence in a paragraph.

Counterargument: But What About Other Perspectives?

Later in this section, we have included an essay by Steven Krause who offers a thorough explanation of what counterargument is (and how to respond to it). In summary, a strong arguer should not be afraid to consider perspectives that either challenge or completely oppose his or her own claim. When you respectfully and thoroughly discuss perspectives or research that counters your own claim or even weaknesses in your own argument, you are showing yourself to be an ethical arguer. The following are some things of which counter arguments may consist:

- summarizing opposing views;

- explaining how and where you actually agree with some opposing views;

- acknowledging weaknesses or holes in your own argument.

You have to be careful and clear that you are not conveying to a reader that you are rejecting your own claim. It is important to indicate that you are merely open to considering alternative viewpoints. Being open in this way shows that you are an ethical arguer – you are considering many viewpoints.

Types of Counterarguments

Counterarguments can take various forms and serve a range of purposes such as:

- Could someone disagree with your claim? If so, why? Explain this opposing perspective in your own argument, and then respond to it.

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from any of the facts or examples you present? If so, what is that different conclusion? Explain this different conclusion and then respond to it.

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims? If so, which ones would they question? Explain and then respond.

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue? If so, what might their explanation be? Describe this different explanation, and then respond to it.

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position? If so, what is it? Cite and discuss this evidence and then respond to it.

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, that does not necessarily mean that you have a weak argument. It means ideally, and as long as your argument is logical and valid, that you have a counterargument. Good arguments can and do have counterarguments; it is important to discuss them. But you must also discuss and then respond to those counterarguments.

Response to Counterargument: I See That, But…

Just as it is important to include counterargument to show that you are fair-minded and balanced, you must respond to the counterargument so that a reader clearly sees that you are not agreeing with the counterargument and thus abandoning or somehow undermining your own claim. Failure to include the response to counterargument can confuse the reader. There are several ways to respond to a counterargument such as:

- Concede to a specific point or idea from the counterargument by explaining why that point or idea has validity. However, you must then be sure to return to your own claim, and explain why even that concession does not lead you to completely accept or support the counterargument;

- Reject the counterargument if you find it to be incorrect, fallacious, or otherwise invalid;

- Explain why the counterargument perspective does not invalidate your own claim.

A Note About Where to Put the Counterargument

It is certainly possible to begin the argument section (after the background section) with your counterargument + response instead of placing it at the end of your essay. Some people prefer to have their counterargument first where they can address it and then spend the rest of their essay building their own case and supporting their own claim. However, it is just as valid to have the counterargument + response appear at the end of the paper after you have discussed all of your reasons.

What is important to remember is that wherever you place your counterargument, you should:

- Address the counterargument(s) fully:

- Explain what the counter perspectives are;

- Describe them thoroughly;

- Cite authors who have these counter perspectives;

- Quote them and summarize their thinking.

- Then, respond to these counterarguments:

- Make it clear to the reader of your argument why you concede to certain points of the counterargument or why you reject them;

- Make it clear that you do not accept the counterargument, even though you understand it;

- Be sure to use transitional phrases that make this clear to your reader.

Responding to Counterarguments

You do not need to attempt to do all of these things as a way to respond. Instead, choose the response strategy that makes the most sense to you for the counterargument that you find:

- If you agree with some of the counterargument perspectives, you can concede some of their points. (“I do agree that ….”, “Some of the points made by X are valid…..”) You could then challenge the importance/usefulness of those points;

- “However, this information does not apply to our topic because…”

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains different evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the evidence that the counterarguer presents;

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains a different interpretation of evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the interpretation of the evidence that your opponent (counterarguer) presents.

If the counterargument is an acknowledgement of evidence that threatens to weaken your argument, you must explain why and how that evidence does not, in fact, invalidate your claim.

It is important to use transitional phrases in your paper to alert readers when you’re about to present a counterargument. It’s usually best to put this phrase at the beginning of a paragraph such as:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

- A perspective that challenges the idea that…

Transitional phrases will again be useful to highlight your shift from counterargument to response:

- Indeed, some of those points are valid. However, . . .

- While I agree that . . . , it is more important to consider . . .

- These are all compelling points. Still, other information suggests that . .

- While I understand . . . , I cannot accept the evidence because . . .[1]

In the section that follows, the Toulmin method of argumentation is described and further clarifies the terms discussed in this section.

Practice Activity

[h5p id=”44″]

This section contains material from:

Amanda Lloyd and Emilie Zickel. “Basic Structure of Arguments.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/basic-argument-components/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027011022/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/basic-argument-components/

Jeffrey, Robin. “Counterargument and Response.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/questions-for-thinking-about-counterarguments/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027003319/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/questions-for-thinking-about-counterarguments/

OER credited the texts above includes:

Jeffrey, Robin. About Writing: A Guide. Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711210756/https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/

- This section originally contained the following attribution: This page contains material from “About Writing: A Guide” by Robin Jeffrey, OpenOregon Educational Resources, Higher Education Coordination Commission: Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development is licensed under CC BY 4.0. ↵

Learning Objectives

- Identify drafting strategies that improve writing.

- Use drafting strategies to prepare the first draft of an essay.

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing.

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original whenever they open a blank document on their computers. You have already recovered from empty page syndrome because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Getting Started: Strategies For Drafting

Your objective for this portion of the chapter is to draft the body paragraphs of a standard five-paragraph essay. A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and type it before revising. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

The writing process is so beneficial to writers because it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful for writing a multipage report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

Tip

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Connecting the Pieces: Writing at Work

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss.

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss.

Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer, though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogues to appeal to buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalogue will differ from those in a clothing catalogue for mature adults.

Exercise 1

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 3.2 "Outlining", describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then, keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

- My purpose: __________________________

- My audience: _________________________

Setting Goals for Your First Draft

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you can make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Connecting the Pieces: Writing at Work

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

Tip

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you can use it confidently during the revision stage of the writing process.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you can use it confidently during the revision stage of the writing process.

Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make so you can tinker with the text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you creatively leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest tells what the essay is about and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will also read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 4.

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. Using a topic sentence in each essay paragraph is the standard rule in college writing. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph, even if it is the first item in your formal outline.

Tip

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas.

However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. By its nature, writing a draft is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be a paragraph's first, middle, or final sentence. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement or order. When you organize information according to an order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

Tip

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs.

For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6: Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

Paragraphs

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Tip

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what your instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

Exercise 2

Use the Internet to find examples of the following items to build your sense of appropriate paragraph length. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations or notes.

- A news article written in short paragraphs. Take notes on or annotate your selection with your observations about the effect of combining paragraphs that develop the same topic idea. Explain how effective those paragraphs would be.

- A long paragraph from a scholarly work that you identify through an academic search engine. Annotate it with your observations about the author’s paragraphing style.

Starting Your First Draft

Now, we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mindset to start.

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised it. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 3.4 "Revising and Editing" when she revises it.

Tip

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish

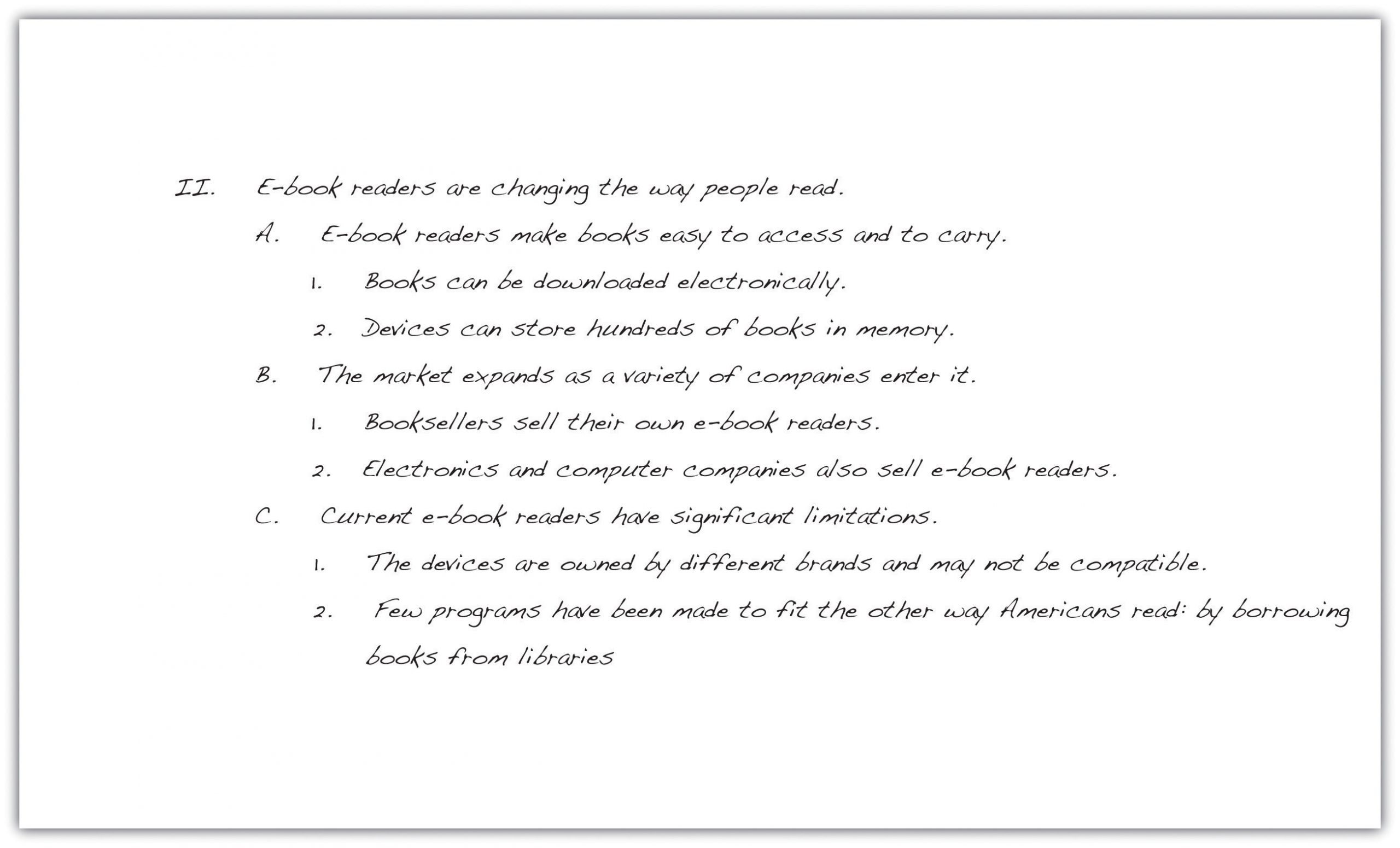

With her thesis statement, purpose, and audience notes in front of her, Mariah looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is her portion for the first body paragraph. The Roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

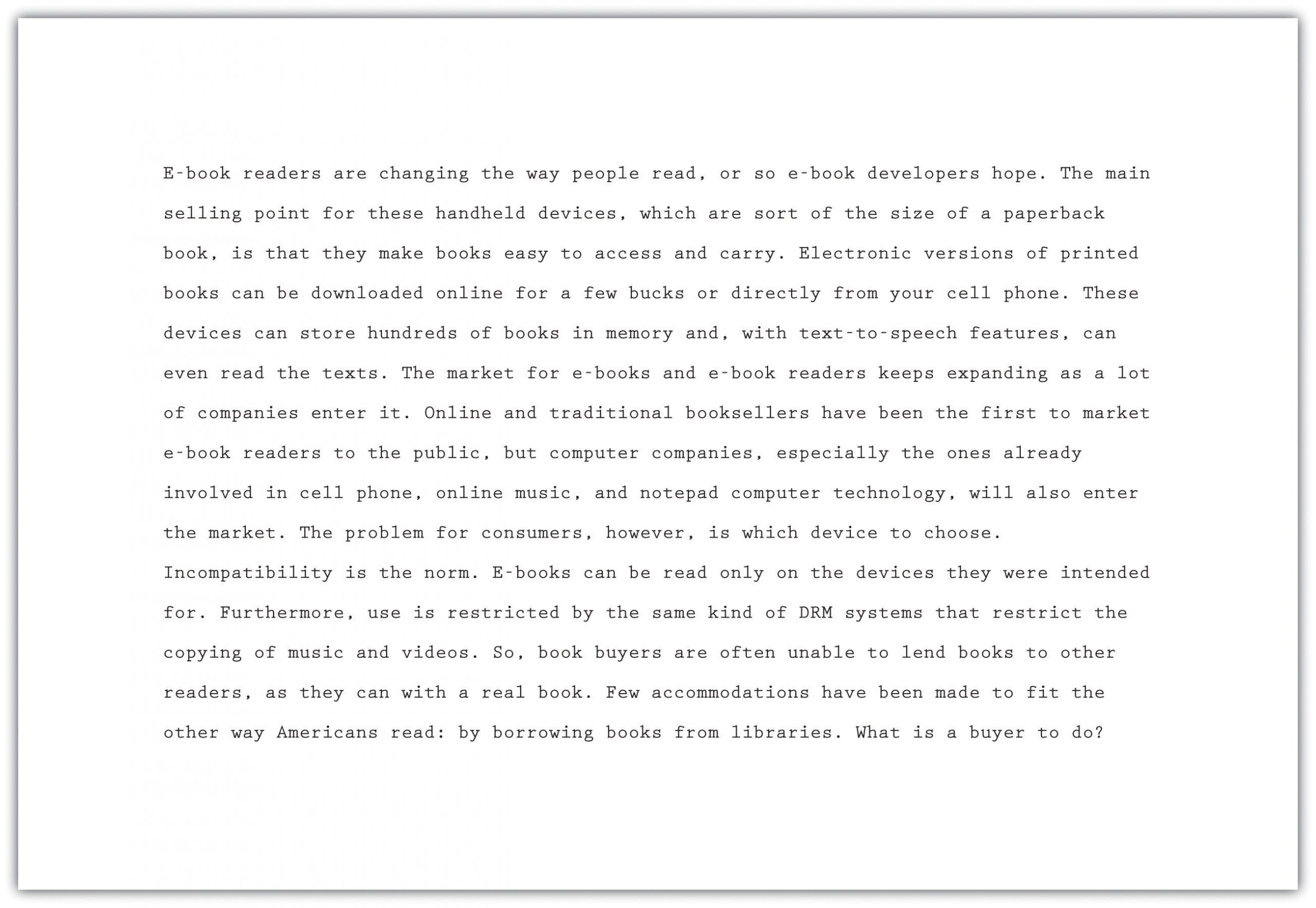

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

Tip

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then, use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then, use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Exercise 3

Study how Mariah transitioned from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then, copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

Tip

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded the Roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using the Roman numeral IV from her outline.

Exercise 4

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then, answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish ). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Writing Your Own First Draft

Now, you may begin your own first draft if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include an essay's key structural parts: a thesis statement in your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then, add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a Roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the subpoints of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Strategies for drafting body paragraphs for a standard 5-paragraph essay

- Offers approaches/tips for developing ideas

- Discusses key parts of drafts

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original whenever they open a blank document on their computers. You have already recovered from empty page syndrome because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Getting Started: Strategies For Drafting

A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and type it before revising. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

The writing process is so beneficial to writers because it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful for writing a multipage report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

Tip

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Connecting the Pieces: Writing at Work

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss.

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss.

Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer, though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogues to appeal to buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalogue will differ from those in a clothing catalogue for mature adults.

Exercise 1

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 3.2 "Outlining", describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then, keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

- My purpose: __________________________

- My audience: _________________________

Setting Goals for Your First Draft

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you can make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Connecting the Pieces: Writing at Work

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

Tip

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you can use it confidently during the revision stage of the writing process.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you can use it confidently during the revision stage of the writing process.

Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make so you can tinker with the text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you creatively leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest tells what the essay is about and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will also read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 4.

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. Using a topic sentence in each essay paragraph is the standard rule in college writing. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph, even if it is the first item in your formal outline.

Tip

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas.

However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. By its nature, writing a draft is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be a paragraph's first, middle, or final sentence. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement or order. When you organize information according to an order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

Tip

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs.

For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6: Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

Paragraphs

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Tip

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what your instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

Exercise 2

Use the Internet to find examples of the following items to build your sense of appropriate paragraph length. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations or notes.

- A news article written in short paragraphs. Take notes on or annotate your selection with your observations about the effect of combining paragraphs that develop the same topic idea. Explain how effective those paragraphs would be.

- A long paragraph from a scholarly work that you identify through an academic search engine. Annotate it with your observations about the author’s paragraphing style.

Starting Your First Draft

Now, we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mindset to start.

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised it. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 3.4 "Revising and Editing" when she revises it.

Tip

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish

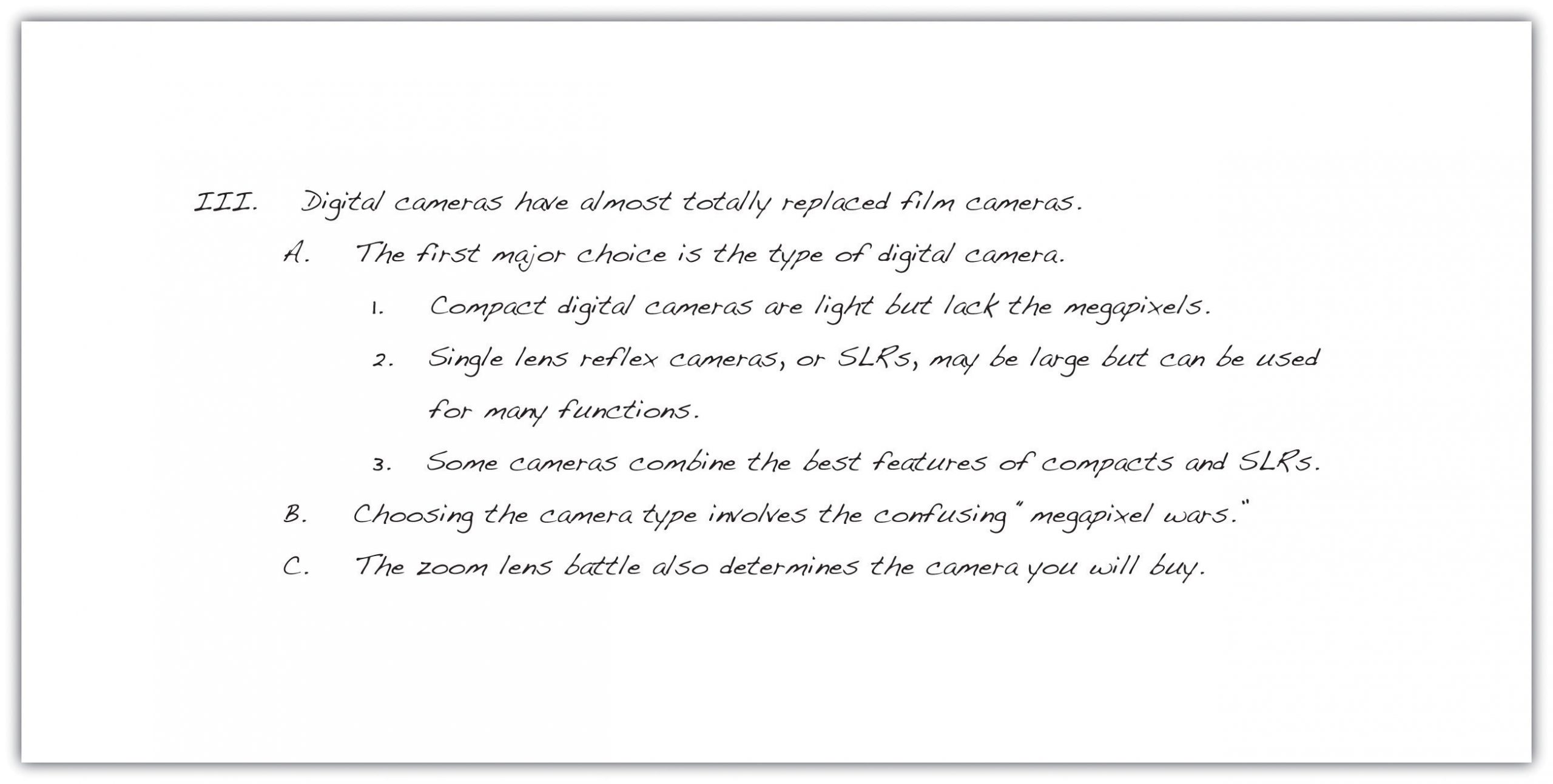

With her thesis statement, purpose, and audience notes in front of her, Mariah looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is her portion for the first body paragraph. The Roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

Tip

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then, use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then, use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Exercise 3

Study how Mariah transitioned from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then, copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

Tip

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

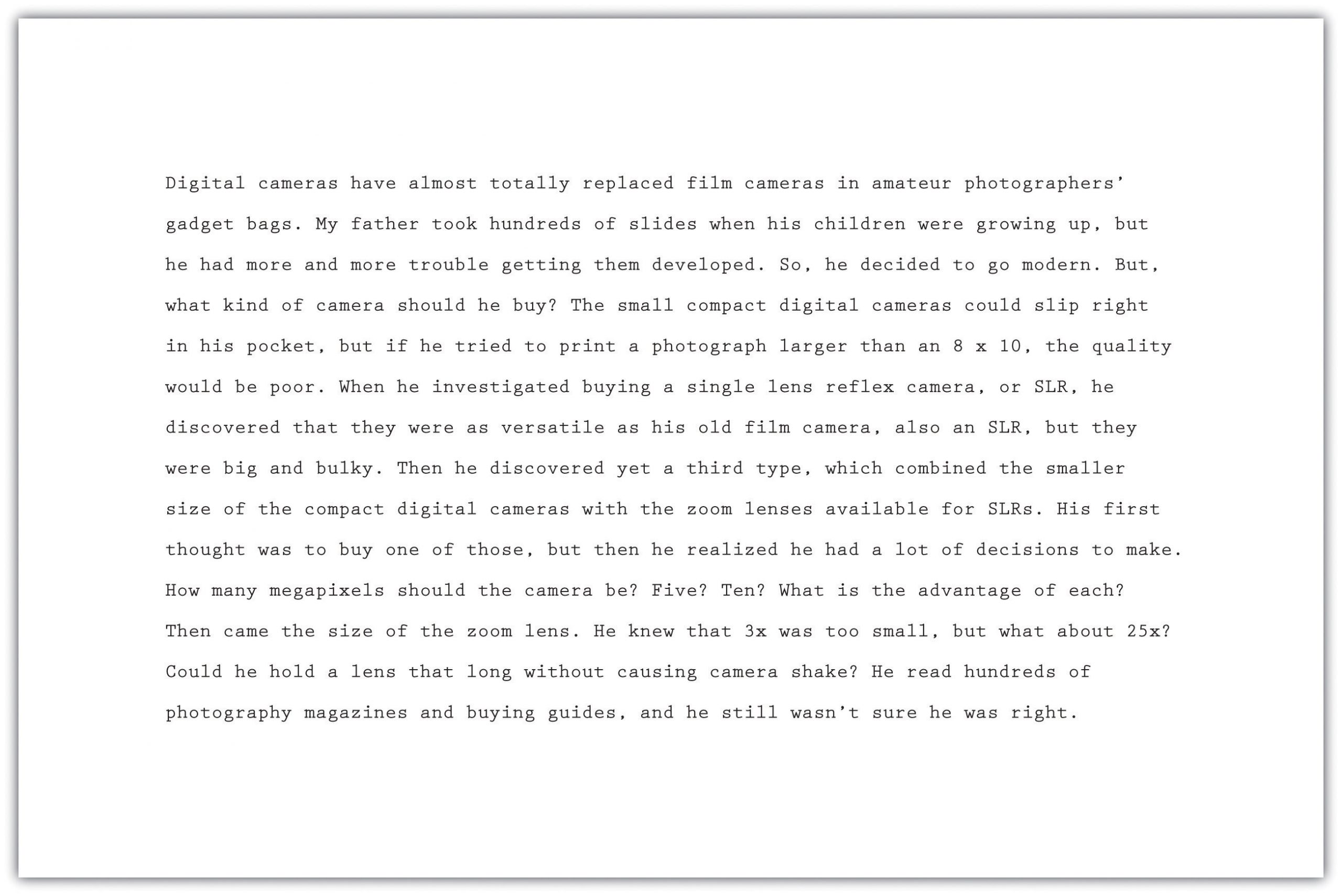

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded the Roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

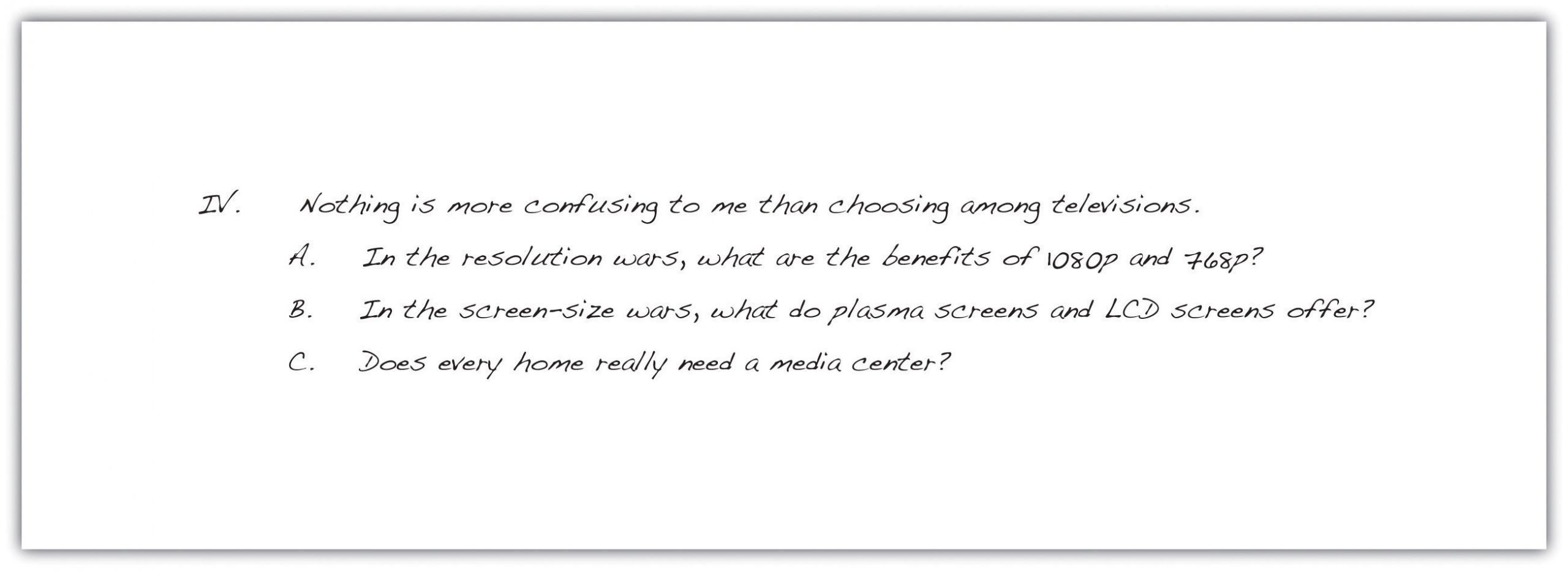

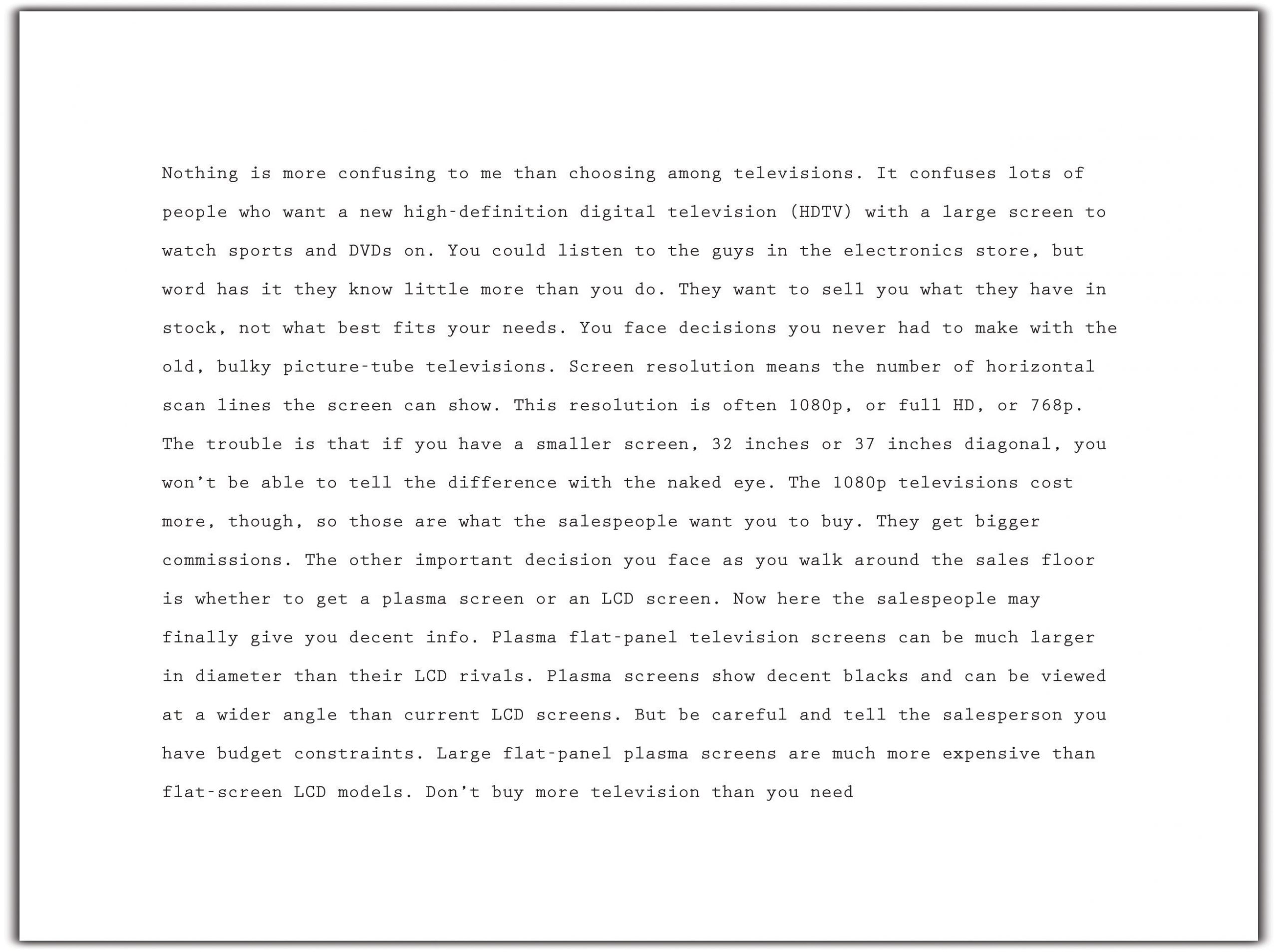

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using the Roman numeral IV from her outline.

Exercise 4

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then, answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 4: Writing Essays From Start to Finish ). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Writing Your Own First Draft

Now, you may begin your own first draft if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include an essay's key structural parts: a thesis statement in your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then, add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a Roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the subpoints of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.