Developing a Research Strategy

Sarah’s art history professor just assigned the course project and Sarah is delighted that it isn’t the typical research paper. Rather, it involves putting together a website to help readers understand a topic. It will certainly help Sarah get a grasp on the topic herself. Learning by attempting to teach others, she agrees, might be a good idea. The professor wants the website to be written for people who are interested in the topic and with backgrounds similar to the students in the course. Sarah likes that a target audience is defined, and since she has a good idea of what her friends might understand and what they would need more help with, she thinks it will be easier to know what to include in her site…well, at least easier than writing a paper for an expert like her professor.

An interesting feature of this course is that the professor has formed the students into teams. Sarah wasn’t sure she liked this idea at the beginning, but it seems to be working out okay. Sarah’s team has decided that their topic for this website will be 19th century women painters. Her teammate Chris seems concerned: “Isn’t that an awfully big topic?” The team checks with the professor who agrees they would be taking on far more than they could successfully explain on their website. He suggests they develop a draft thesis statement to help them focus, and after several false starts, they come up with:

The involvement of women painters in the Impressionist movement had an effect upon the subjects portrayed.

They decide this sounds more manageable. Because Sarah doesn’t feel comfortable on the technical aspects of setting up the website, she offers to start locating resources that will help them to develop the site’s content. The next time the class meets, Sarah tells her teammates what she has done so far:

“I thought I’d start with some scholarly sources, since they should be helpful, right? I put a search into the online catalog for the library, but nothing came up! The library should have books on this topic, shouldn’t it? I typed the search in exactly as we have it in our thesis statement. That was so frustrating. Since that didn’t work, I tried Google, and put in the search. I got over 8 million results, but when I looked over the ones on the first page, they didn’t seem very useful. One was about the feminist art movement in the 1960s, not during the Impressionist period. The results all seemed to have the words I typed highlighted, but most really weren’t useful. I am sorry I don’t have much to show you. Do you think we should change our topic?”

Alisha suggests that Sarah talk with a reference librarian. She mentions that a librarian came to talk to one of her other classes about doing research, and it was really helpful. Alisha thinks that maybe Sarah shouldn’t have entered the entire thesis statement as the search, and maybe she should have tried databases to find articles. The team decides to brainstorm all the search tools and resources they can think of.

Here’s what they came up with:

Brainstormed List of Search Tools and Resources

|

Search Tools and Resources |

|---|

|

Wikipedia |

|

Professor |

|

Google search |

|

JSTOR database |

Based on your experience, do you see anything you would add?

Sarah and her team think that their list is pretty good. They decide to take it further and list the advantages and limitations of each search tool, at least as far as they can determine.

Brainstormed Advantages and Disadvantages of Search Tools and Resources

|

Search Tools and Resources |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Search Tool |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Wikipedia |

Easy access, list of references |

Professors don’t seem to like it, possibly misinformation |

|

Professor |

The expert! |

Not sure we can get to office hours; we want to appear self-directed |

|

Google search |

Lots of results |

We need a better search term |

|

JSTOR database |

Authoritative, scholarly articles |

None that we know of |

Alisha suggests that Sarah should show the worksheet to a librarian and volunteers to go with her. The librarian, Mr. Harrison, says they have made a really good start, but he can fill them in on some other search strategies that will help them to focus on their topic. He asks if Sarah and Alisha would like to learn more.

Let’s step back from this case study and think about the elements that someone doing research should plan before starting to enter search terms in Google, Wikipedia, or even a scholarly database. There is some preparation you can do to make things go much more smoothly than they have for Sarah.

Self-Reflection

As you work through your own research quests, it is very important to be self-reflective. Consider:

- What do you really need to find?

- Do you need to learn more about the general subject before you can identify the focus of your search?

- How thoroughly did you develop your search strategy?

- Did you spend enough time finding the best tools to search?

- What is going really well, so well that you’ll want to remember to do it in the future?

Another term for what you are doing is metacognition, or thinking about your thinking. Reflect on what Sarah is going through. Does some of it sound familiar based on your own experiences? You may already know some of the strategies presented here. Do you do them the same way? How does it work? What pieces are new to you? When might you follow this advice? Don’t just let the words flow over you; rather, think carefully about the explanation of the process. You may disagree with some of what you read. If you do, follow through and test both methods to see which provides better results.

Selecting Search Tools

After you have thought the planning process through more thoroughly, think about the best place to find information for your topic and for the type of paper. Part of planning to do research is determining which search tools will be the best ones to use. This applies whether you are doing scholarly research or trying to answer a question in your everyday life, such as what would be the best place to go on vacation. “Search tools” might be a bit misleading since a person might be the source of the information you need. Or it might be a web search engine, a specialized database, an association—the possibilities are endless. Often people automatically search Google first, regardless of what they are looking for. Choosing the wrong search tool may just waste your time and provide only mediocre information, whereas other sources might provide really spot-on information and quickly, too. In some cases, a carefully constructed search on Google, particularly using the advanced search option, will provide the necessary information, but other times it won’t. This is true of all sources: make an informed choice about which ones to use for a specific need.

So, how do you identify search tools? Let’s begin with a first-rate method. For academic research, talking with a librarian or your professor is a great start. They will direct you to those specialized tools that will provide access to what you need. If you ask a librarian for help, they may also show you some tips about searching in the resources. This section will cover some of the generic strategies that will work in many search tools, but a librarian can show you very specific ways to focus your search and retrieve the most useful items.

If neither your professor nor a librarian is available when you need help, take a look at the TAMU Libraries website. There is a Help button in the top right corner of the website that will direct you to assistance via phone, chat, text, and email. Under the Guides button, you’ll find class- and subject-related guides that list useful databases and other resources for particular classes and majors to assist researchers. There is also a directory of the databases the library subscribes to and the subjects they cover. Take advantage of the expertise of librarians by using such guides. Novice researchers usually don’t think of looking for this type of help and, as a consequence, often waste time.

When you are looking for non-academic material, consider who cares about this type of information. Who works with it? Who produces it or the help guides for it? Some sources are really obvious and you are already using them—for example, if you need information about the weather in London three days from now, you might check Weather.com for London’s forecast. You don’t go to a library (in person or online), and you don’t do a research database search. For other information you need, think the same way. Are you looking for anecdotal information on old railroads? Find out if there is an organization of railroad buffs. You can search on the web for this kind of information or, if you know about and have access to it, you could check the Encyclopedia of Associations. This source provides entries for all U.S. membership organizations which can quickly lead you to a potentially wonderful source of information. Librarians can point you to tools like these.

Consider Asking an Expert

Have you thought about using people, not just inanimate sources, as a way to obtain information? This might be particularly appropriate if you are working on an emerging topic or a topic with local connections. There are a variety of reasons that talking with someone will add to your research.

For personal interactions, there are other specific things you can do to obtain better results. Do some background work on the topic before contacting the person you hope to interview. The more familiarity you have with your topic and its terminology, the easier it will be to ask focused questions. Focused questions are important if you want to get into the meat of what you need. Asking general questions because you think the specifics might be too detailed rarely leads to the best information. Acknowledge the time and effort someone is taking to answer your questions, but also realize that people who are passionate about subjects enjoy sharing what they know. Take the opportunity to ask experts about sources they would recommend. One good place to start is with the librarians at the Texas A&M University Libraries. Visit the library information page for details on how to contact a librarian.[1]

Determining Search Concepts and Keywords

Once you’ve selected some good resources for your topic, and possibly talked with an expert, it is time to move on to identify words you will use to search for information on your topic in various databases and search engines. This is sometimes referred to as building a search query. When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Don’t enter an entire sentence or a full question. Different databases and search engines process such queries in different ways, but many look for the entire phrase you enter as a complete unit rather than the component words. While some will focus on just the important words, such as Sarah’s Google search that you read about earlier in this chapter, the results are often still unsatisfactory. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic. In addition, think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term doesn’t produce any or enough results. This may sound strange since, if you are looking for information using a Web search engine, you almost always get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

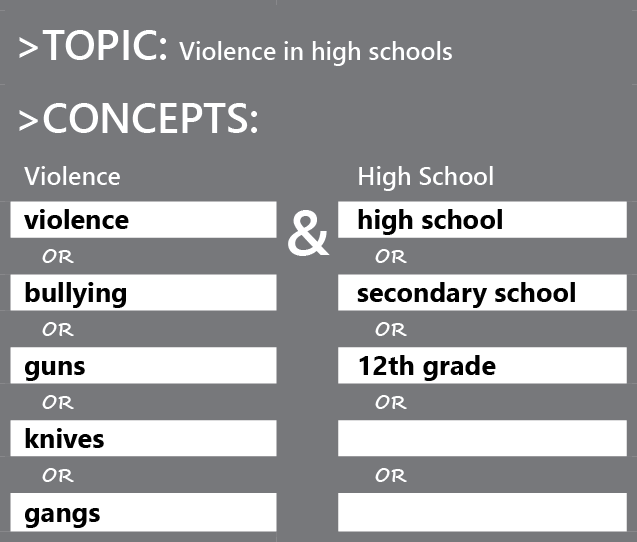

The worksheet in Figure 7.4.1[2] is an example of a process you can use to come up with search terms. It illustrates how you might think about the topic of violence in high schools. Notice that this exact phrase is not what will be used for the search. Rather, it is a starting point for identifying the terms that will eventually be used.

Example Search Term Brainstorming Worksheet

Exercises

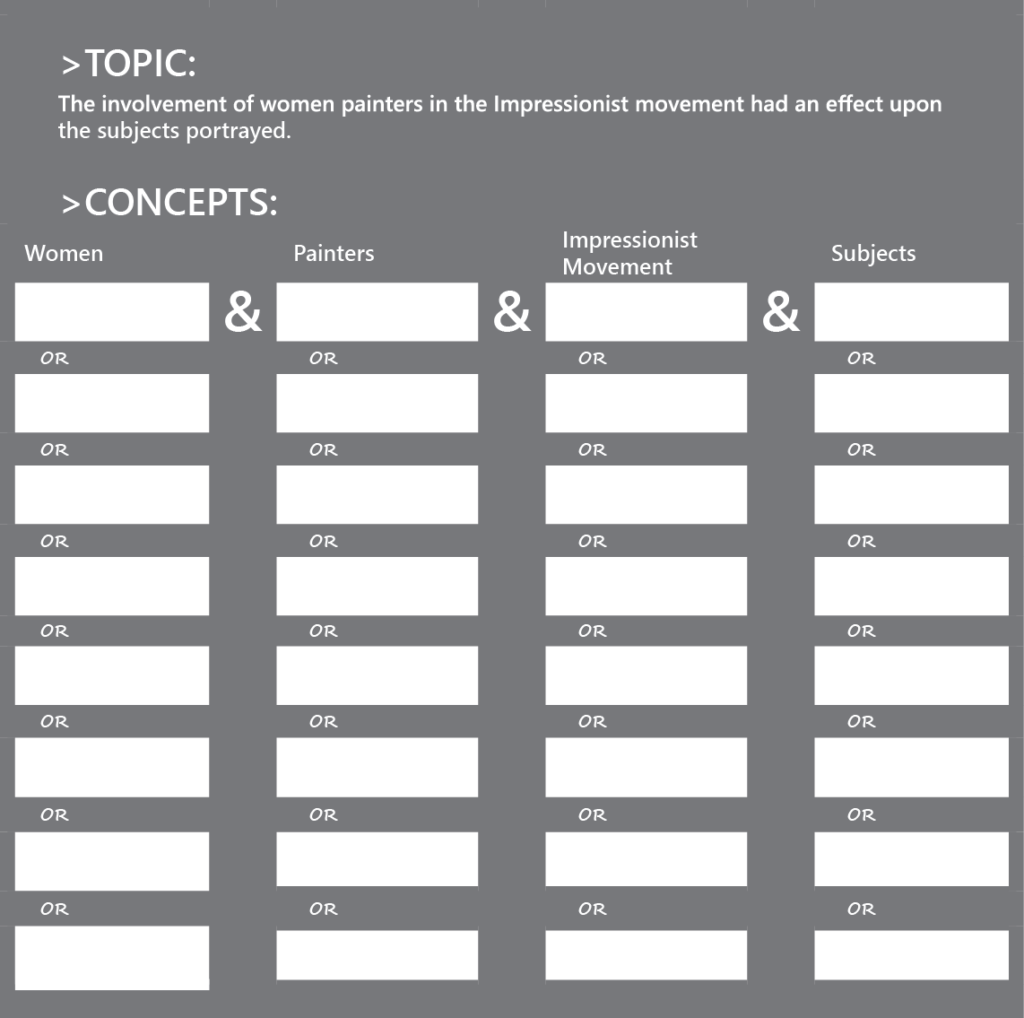

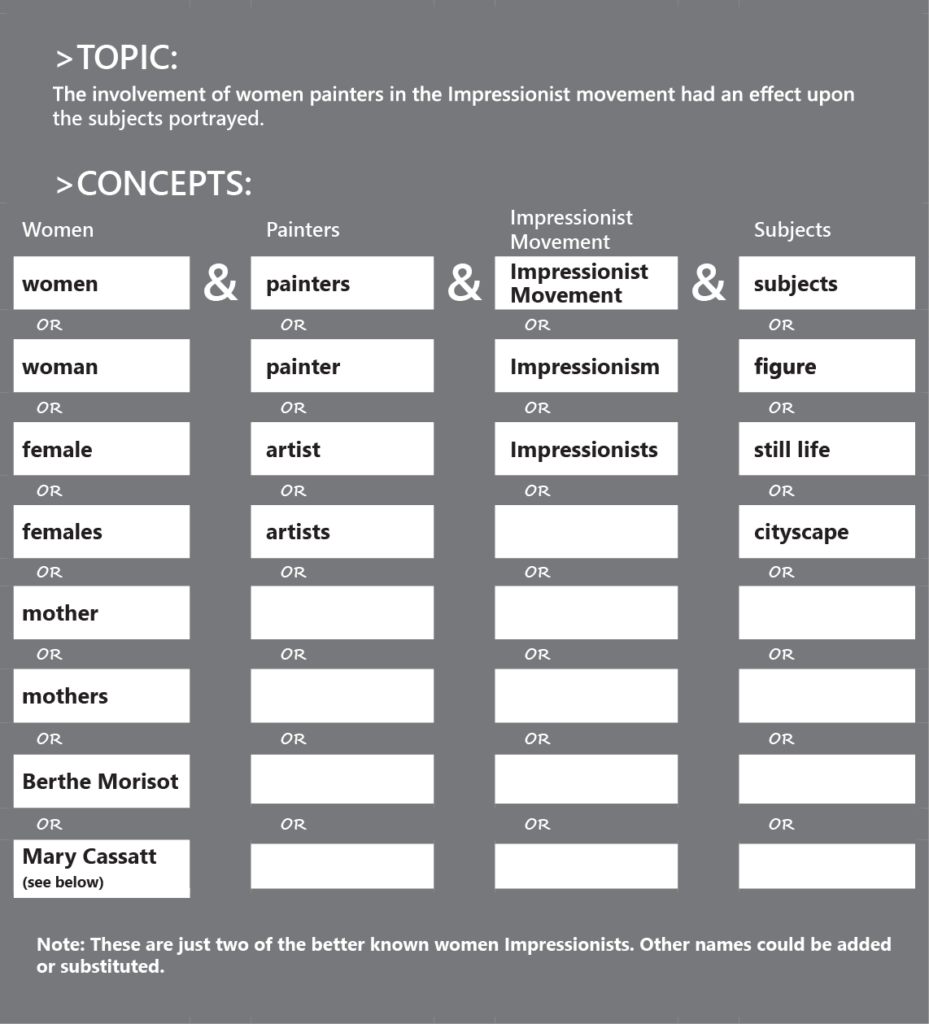

Now, use a clean copy of the same worksheet (Figure 7.4.2)[3] to think about the topic Sarah’s team is working on. How might you divide their topic into concepts and then search terms? Keep in mind that the number of concepts will depend on what you are searching for and that the search terms may be synonyms or narrower terms. Occasionally, you may be searching for something very specific, and in those cases, you may need to use broader terms as well. Jot down your ideas, then compare what you have written to the information on the second, completed worksheet (Figure 7.4.3)[4] and identify three differences.

Boolean Operators

Once you have the concepts you want to search, you need to think about how you will enter them into the search box. Often, but not always, Boolean operators will help you. You may be familiar with Boolean operators as they provide a way to link terms. There are three Boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT. (Note: Some databases require Boolean operators to be in all caps while others will accept the terms in either upper or lower case.

AND

We will start by capturing the ideas of the women creating the art. We will use women painters and women artists as the first step in our sample search. You could do two separate searches by typing one or the other of the terms into the search box of whatever tool you are using:

women painters women artists

You would end up with two separate results lists and have the added headache of trying to identify unique items from the lists. You could also search on the phrase:

women painters AND women artists

But once you understand Boolean operators, that last strategy won’t make as much sense as it seems to. The first Boolean operator is AND. AND is used to get the intersection of all the terms you wish to include in your search. With this example,

women painters AND women artists

you are asking that the items you retrieve have both of those terms. If an item only has one term, it won’t show up in the results. This is not what the searcher had in mind—she is interested in both artists and painters because she doesn’t know which term might be used. She doesn’t intend that both terms have to be used. Let’s go on to the next Boolean operator, which will help us out with this problem.

OR

OR is used when you want at least one of the terms to show up in the search results. If both do, that’s fine, but it isn’t a condition of the search. So OR makes a lot more sense for this search:

women painters OR women artists

Now, if you want to get fancy with this search, you could use both AND as well as OR:

women AND (painters OR artists)

The parentheses mean that these two concepts, painters and artists, should be searched as a unit, and the search results should include all items that use one word or the other. The results will then be limited to those items that contain the word women. If you decide to use parentheses for appropriate searches, make sure that the items contained within them are related in some way. With OR, as in our example, it means either of the terms will work. With AND, it means that both terms will appear in the document.

Exercise

Type both of the searches above in Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) and compare the results.

- Were they the same?

- If not, can you determine what happened?

- Which results list looked better?

Here is another example of a search string using both parentheses and two Boolean operators:

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens)

In this search, you are looking for entrepreneurial initiatives connected with people in their teens. Because there are so many ways to categorize this age group, it makes sense to indicate that either of these terms should appear in the results along with entrepreneurship.

Exercise

The search string above isn’t perfect. Can you pick out two problems with the search terms?

NOT

The third Boolean operator, NOT, can be problematic. NOT is used to exclude items from your search. If you have decided, based on the scope of the results you are getting, to focus only on a specific aspect of a topic, use NOT, but be aware that items are being lost in this search.

For example, if you entered

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens) NOT adults

you might lose some good results.

Exercise

Why might you lose some good results using the search above?

Other Helpful Search Techniques

Using Boolean operators isn’t the only way you can create more useful searches. In this section, we will review several others.

Truncation

In this search:

entrepreneurs AND (adolescents OR teens)

you might think that the items that are retrieved from the search can refer to entrepreneurs and to terms from the same root, like entrepreneurship. But because computers are very literal, they usually look for the exact terms you enter. While some search engines like Google are moving beyond this model, library databases tend to require more precision. Truncation, or searching on the root of a word and whatever follows, is how you can tell the database to do this type of search.

So, if you search on:

entrepreneur* AND (adolescents OR teens)

You will get items that refer to entrepreneur, but also entrepreneurship.

Look at these examples:

adolescen* educat*

Think of two or three words you might retrieve when searching on these roots. It is important to consider the results you might get and alter the root if need be. An example of this is polic*. Would it be a good idea to use this root if you wanted to search on policy or policies? Why or why not?

In some cases, a symbol other than an asterisk is used. To determine what symbol to use, check the help section in whatever resource you are using. The topic should show up under the truncation or stemming headings.

Phrase Searches

Phrase searches are particularly useful when searching the web. If you put the exact phrase you want to search in quotation marks, you will only get items with those words as a phrase and not items where the words appear separately in a document, website, or other resource. Your results will usually be fewer, although surprisingly, this is not always the case.

Exercise

Try these two searches in the search engine of your choice:

- essay exam

- “essay exam”

Was there a difference in the quality and quantity of results?

If you would like to find out if the database or search engine you are using allows phrase searching and the conventions for doing so, search the help section. These help tools can be very, well, helpful!

Advanced Searches

Advanced searching allows you to refine your search query and prompts you for ways to do this. Consider the basic Google search box. It is very minimalistic, but that minimalism is deceptive. It gives the impression that searching is easy and encourages you to just enter your topic without much thought to get results. You certainly do get many results, but are they really good results? Simple search boxes do many searchers a disfavor. There is a better way to enter searches.

Advanced search screens show you many of the options available to you to refine your search and, therefore, get more manageable numbers of better items. Many web search engines include advanced search screens, as do databases for searching research materials. Advanced search screens will vary from resource to resource and from web search engine to research database, but they often let you search using:

- Implied Boolean operators (for example, the “all the words” option is the same as using the Boolean AND);

- Limiters for date, domain (.edu, for example), type of resource (articles, book reviews, patents);

- Field (a field is a standard element, such as title of publication or author’s name);

- Phrase (rather than entering quote marks) Let’s see how this works in practice.

Practical Application: Google Searches

Go to the advanced search option in Google. You can find it at http://www.google.com/advanced_search

Take a look at the options Google provides to refine your search. Compare this to the basic Google search box. One of the best ways you can become a better searcher for information is to use the power of advanced searches, either by using these more complex search screens or by remembering to use Boolean operators, phrase searches, truncation, and other options available to you in most search engines and databases.

While many of the text boxes at the top of the Google Advanced Search page mirror concepts already covered in this section (for example, “this exact word or phrase” allows you to omit the quotes in a phrase search), the options for narrowing your results can be powerful. You can limit your search to a particular domain (such as .edu for items from educational institutions) or you can search for items you can reuse legally (with attribution, of course!) by making use of the “usage rights” option. However, be careful with some of the options as they may excessively limit your results. If you aren’t certain about a particular option, try your search with and without using it and compare the results. If you use a search engine other than Google, check to see if it offers an advanced search option: many do.

Subject Headings

In the section on advanced searches, you read about field searching. To explain further, if you know that the last name of the author whose work you are seeking is Wood, and that he worked on forestry-related topics, you can do a far better search using the author field. Just think what you would get in the way of results if you entered a basic search such as forestry AND wood. It is great to use the appropriate Boolean operator, but oh, the results you will get! But what if you specified that wood had to show up as part of the author’s name? This would limit your results quite a bit.

So what about forestry? Is there a way to handle that using a field search? The answer is yes. Subject headings are terms that are assigned to items to group them. An example is cars—you could also call them autos, automobiles, or even more specific labels like SUVs or vans. You might use the Boolean operator OR and string these all together. But if you found out that the sources you are searching use automobiles as the subject heading, you wouldn’t have to worry about all these related terms, and could confidently use their subject heading and get all the results, even if the author of the piece uses cars and not automobiles.

How does this work? In many databases, a person called an indexer or cataloger scrutinizes and enters each item. This person performs helpful, behind-the-scenes tasks such as assigning subject headings, age levels, or other indicators that make it easier to search very precisely. An analogy is tagging, although indexing is more structured than tagging. If you have tagged items online, you know that you can use any terms you like and that they may be very different from someone else’s tags. With indexing, the indexer chooses from a set group of terms. Obviously, this precise indexing isn’t available for web search engines—it would be impossible to index everything on the web. But if you are searching in a database, make sure you use these features to make your searches more precise and your results lists more relevant. You also will definitely save time.

You may be thinking that this sounds good. Saving time when doing research is a great idea. But how will you know what subject headings exist so you can use them? Here is a trick that librarians use. Even librarians don’t know what terms are used in all the databases or online catalogs that they use, so a librarian’s starting point isn’t very far from yours. But they do know to use whatever features a database provides to do an effective search. They find out about them by acting like a detective.

You’ve already thought about the possible search terms for your information needs. Enter the best search strategy you developed which might use Boolean operators or truncation. Scan the results to see if they seem to be on topic. If they aren’t, figure out what results you are getting that just aren’t right and revise your search. Terms you have searched on often show up in bold face type so they are easy to pick out. Besides checking the titles of the results, read the abstracts (or summaries), if there are any. You may get some ideas for other terms to use. But if your results are fairly good, scan them with the intent to find one or two items that seem to be precisely what you need. Get to the full record (or entry), where you can see all the details entered by the indexers. Figure 7.4.4[5] is an example from the Texas A&M University Libraries’ Quick Search, but keep in mind that the catalog or database you are using may have entries that look very different.

Once you have the “full” record (which does not refer to the full text of the item, but rather the full descriptive details about the book, including author, subjects, date, and place of publication, and so on), look at the subject headings and see what words are used. They may be called descriptors or some other term, but they should be recognizable as subjects. They may be identical to the terms you entered but if not, revise your search using the subject heading words. The result list should now contain items that are relevant for your needs.

It is tempting to think that once you have gone through all the processes around the circle, as seen in the diagram in Figure 7.4.5[6], your information search is done and you can start writing. However, research is a recursive process. You don’t start at the beginning and continue straight through until you end at the end. Once you have followed this planning model, you will often find that you need to alter or refine your topic and start the process again, as seen here:

![Circle divided into four with a box at each corner. Circle part 1: Refine topic [Box: Narrow or broaden scope, Select new aspect of topic] Circle part 2: Concepts [Box: Revise existing concepts, Add or eliminate concepts] Circle part 3: Determine relationships [Box: Boolean operators, Phrase searching] Circle part 4: Variations and refinements [Box: Truncations, field searching, subject headings]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/17355/2024/10/image4-1-1.png)

This revision process may happen at any time before or during the preparation of your paper or other final product. The researchers who are most successful do this, so don’t ignore opportunities to revise.

So let’s return to Sarah and her search for information to help her team’s project. Sarah realized she needed to make a number of changes in the search strategy she was using. She had several insights that definitely led her to some good sources of information for this particular research topic. Can you identify the good ideas she implemented?

This section contains material from:

Bernnard, Deborah, Greg Bobish, Jenna Hecker, Irina Holden, Allison Hosier, Trudi Jacobson, Tor Loney, and Daryl Bullis. The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014. http://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711202425/https://milneopentextbooks.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/

Media Attributions

- Bullspotting

- https://library.tamu.edu ↵

- “Concept Brainstorming,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Blank Concept Brainstorming Worksheet,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Completed Concept Brainstorming Worksheet” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Full Record Entry for a Book” is a reproduction from July 2019 of a Texas A&M University Libraries catalog entry from the Texas A&M University Libraries Quick Search. https://library.tamu.edu. ↵

- “Planning Model” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

Chapter Description

Discusses local and local revision, provides some techniques, discusses peer feedback and how to construct group feedback, introduces reverse outlining and cutting "fluff'

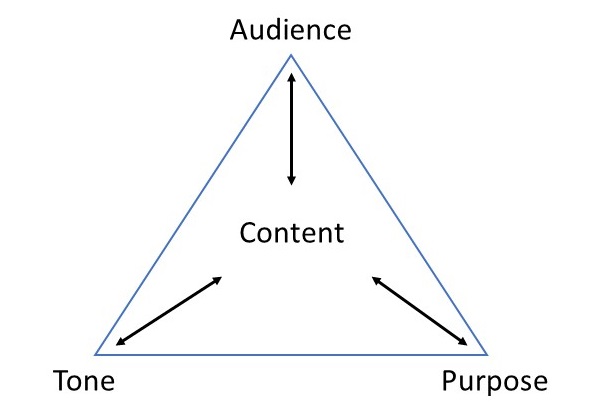

Now that you have determined the assignment parameters, it’s time to begin drafting. While doing so, it is important to remain focused on your topic and thesis in order to guide your reader through the essay. Imagine reading one long block of text with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay (see Figure 2.4.1).[1]

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point or thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to classify

- to analyze

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A classification shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials, using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a classification should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document without quoting the original text. Keep in mind that classification moves beyond simple summary to be informative.

An analysis, on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis, instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing—synthesis—combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of classifying, analysis, and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to classify, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about the audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions. For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Example A

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think I caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Example B

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with the intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own essays, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject.

Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience might not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on your intended audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

Demographics

These measure important data about a group of people such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

Education

Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

Prior Knowledge

This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

Expectations

These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit a range of attitudes and emotions through prose--from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers convey their attitudes and feelings with useful devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Exercise

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

"Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just seven percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelts and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction."

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. When applied to that audience of third graders, you would choose simple content that the audience would easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone.

The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Practice Activity

[h5p id="6"]

Practice Activity

[h5p id="7"]

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition. 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711203012/https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/

Additional Resources

- Causal Thesis Statements PowerPoint, available in Blackboard

- Essay Planning Sheet, available by request

Introduction

The writing genre for this chapter is the analytical report. The broad purpose of an analytical report is to inform and analyze—that is, to teach your readers (your audience) about a subject by providing information based on facts supported by evidence and then drawing conclusions about the significance of the information you provide. As an academic and professional genre, reports are necessarily objective, which can make for dry reading. Consider the writing identity that you have been developing throughout this course as you tackle this genre. In what ways can you give your report voice? In what ways can you acknowledge or challenge the conventions of the genre?

You have likely written or presented a report at some point in your life as a student; perhaps you wrote a lab report on a science experiment, presented research you conducted, or analyzed a book you read. While some reports seek to inform readers about a topic, an analytical report examines a subject or an issue by considering its causes and effects, by comparing and contrasting, or by discussing a problem and proposing one or more solutions.

11.1 Information and Critical Thinking

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between fact and opinion.

- Recognize bias in reading and in yourself.

- Ask critical thinking questions to explore an idea for a report.

Knowledge in the social and natural sciences and technical fields is often focused on data and ideas that can be verified by observing, measuring, and testing. Accordingly, writers in these fields place high value on neutral and objective case analysis and inferences based on the careful examination of data. Put another way, writers describe and analyze results as they understand them. Likewise, writers in these fields avoid subjectivity, including personal opinions, speculations, and bias. As the writer of an analytical report, you need to know the difference between fact and opinion, be able to identify bias, and think critically and analytically.

Distinguishing Fact from Opinion

An analytical report provides information based on facts. Put simply, facts are statements that can be proven or whose truth can be inferred.

It may be difficult to distinguish fact from opinion or allegation. As a writer, use a critical eye to examine what you read. The following are examples of factual statements:

- Article I, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution specifies that the legislative branch of the government consists of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

- The school board voted to approve the administration’s proposal.

- Facts that use numbers are called statistics. Some numbers are stated directly:

- The earth’s average land and ocean surface temperature in March 2020 was 2.09 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the average surface temperature during the 20th century.

- The total number of ballots cast in the 2020 presidential election was approximately 159 million.

- The survey results showed that 45 percent of first-year students at this university attended every class, whether in person or online.

Other numbers are implied:

- Mercury is the planet closest to the sun.

- College tuition and fees have risen in the past decade.

Factual statements such as those above stand in contrast to opinions, which are statements of belief or value. Opinions form the basis of claims that are supported by evidence in argumentative writing, but they should be avoided in informative and analytical writing. Here are two statements of opinion about an increase in college tuition and fees:

Although tuition and fees have risen, the value of a college education is worth the cost.

The increase in college tuition and fees over the past 10 years has placed an unreasonably heavy financial burden on students.

Both statements indicate that the writer will make an argument. In the first, the writer will defend the increases in college tuition and fees. In the second, the writer will argue that the increases in tuition and fees have made college too expensive. In both arguments, the writer will support the argument with factual evidence.

Want to know more about facts? Read the blog post Fact-Checking 101 by Laura McClure, posted to the TED-Ed website.

Recognizing Bias

In addition to distinguishing between fact and opinion, it is important to recognize bias. Bias is commonly defined as a preconceived opinion about something—a subject, an idea, a person, or a group of people. As the writer of a report, you will learn to recognize bias in yourself and in the information you gather.

Bias in What You Read

Some writing is intentionally biased and intended to persuade, such as the editorials and opinion pieces described above. However, a report and the evidence on which it is based should not be heavily biased. Bias becomes a problem when a source you believe to be neutral, objective, and trustworthy presents information that attempts to sway your opinion. Identifying Bias, posted by Tyler Rablin, is a helpful guide to recognizing bias.

As you consider sources for your report, the following tips can also help you spot bias and read critically:

Determine the writer’s purpose. Is the writer simply informing you or trying to persuade you?

Research the author. Is the writer known for taking a side on the topic of the writing? Is the writer considered an expert?

Distinguish between fact and opinion. Take note of the number of facts and opinions throughout the source.

Pay attention to the language and what the writer emphasizes. Does the author use emotionally loaded, inflammatory words or descriptions intended to sway readers? What do the title, introduction, and any headings tell you about the author’s approach to the subject?

Read multiple sources on the topic. Learn whether the source is leaving out or glossing over important information and credible views.

Look critically at the images and any media that support the writing. Do they reinforce positive or negative aspects of the subject?

Bias in Yourself

Most individuals bring what psychologists call cognitive bias to their interactions with information or with other people. Cognitive bias influences the way people gather and process new information. As you research information for a report, also be aware of confirmation bias. This is the tendency to seek out and accept information that supports (or confirms) a belief you already have and may cause you to ignore or dismiss information that challenges that belief. A related bias is the false consensus effect, which is the tendency to overestimate the extent to which other people agree with your beliefs.

For example, perhaps you believe strongly that college tuition is too high and that tuition should be free at the public colleges and universities in your state. With that belief, you are likely to be more receptive to facts and statistics showing that tuition-free college benefits students by boosting graduation rates and improving financial security after college, in part because the sources may seem more mainstream. However, if you believe strongly that tuition should not be free, you are likely to be more receptive to facts and statistics showing that students who don’t pay for college are less likely to be serious about school and take longer to graduate—again, because the sources may seem more mainstream.

Asking Critical Questions about a Topic for a Report

As you consider a topic for a report, note the ideas that occur to you, interesting information you read, and what you already know. Answer the following questions about potential topics to help you understand a topic in a suitably analytical framework for a report.

- What is/was the cause of ________?

- What is/was the effect of ________?

- How does/did ________ compare or contrast with another similar event, idea, or item?

- What makes/made ________ a problem?

- What are/were some possible solutions to ________?

- What beliefs do I have about ________?

- What aspects of ________ do I need to learn more about to write a report about it?

In the report that appears later in this chapter, student Trevor Garcia analyzes the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Trevor began thinking about his topic with the question What was the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Because he had lived through 2020, he was able to draw upon personal experience: his school closed, his mother was laid off, and his family’s finances were tight. As he researched his question, he moved beyond the information he gathered from his own experiences and discovered that the United States had failed in several key areas. He then answered the questions below to arrive at an analytical framework:

- What was the cause of the poor U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020?

- What was the effect of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020?

- How did the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic compare/contrast with the responses of other countries?

- What are some possible solutions to the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What do I already believe about the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What aspects of the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic do I need to learn more about?

For his report, Trevor chose to focus on the first question: What was the cause of the poor U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020?

11.3 Glance at Genre: Informal and Formal Analytical Reports

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Determine purpose and audience expectations for an analytical report.

- Identify key features of informal and formal reports.

- Define key terms and characteristics of an analytical report.

It is important to understand the purpose of your report, the expectations of the audience, any specific formatting requirements, and the types of evidence you can use.

Defining a Specific Purpose

Your purpose is your reason for writing. The purpose of a report is to inform; as the writer, you are tasked with providing information and explaining it to readers. Many topics are suitable for informative writing—how to find a job, the way a disease spreads within a population, or the items on which people spend the most money. Some textbooks are examples of informative writing, as is much of the reporting you find on reputable news sites.

An analytical report is a type of report. Its purpose is to present and analyze information. An assignment for an analytical report will likely include words such as analyze, compare, contrast, cause, and/or discuss, indicating the specific purpose of the report. Here are a few examples:

- Discuss and analyze potential career paths with strong employment prospects for young adults.

- Compare and contrast proposals to reduce binge drinking among college students.

- Analyze the Cause-and-effect of injuries on construction sites and the effects of efforts to reduce workplace injuries.

- Discuss the Effect of the 1965 Voting Rights Act on voting patterns among U.S. citizens of color.

- Analyze the success and failure of strategies used by the major political parties to encourage citizens to vote.

Tuning In to Audience Expectations

The audience for your report consists of the people who will read it or who could read it. Are you writing for your instructor? For your classmates? For other students and teachers in professional fields or academic disciplines? For people in your community? Whoever your readers are, they expect you to do the following:

Have an idea of what they already know about your topic, and adjust your writing as needed. If readers are new to the topic, they expect you to provide necessary background information. If they are knowledgeable about the topic, they will expect you to cover the background quickly.

Provide reliable information in the form of specific facts, statistics, and examples. Whether you present your own research or information from other sources, readers expect you to have done your homework in order to supply trustworthy information.

Define terms, especially if audience members may be unfamiliar with your topic.

Structure your report in a logical way. It should open with an introduction that tells readers the subject and should follow a logical structure.

Adopt an objective stance and neutral tone, free of any bias, personal feelings, or emotional language. By demonstrating objectivity, you show respect for your readers’ knowledge and intelligence, and you build credibility and trust, or ethos, with them.

Present and cite source information fairly and accurately.

Informal Reports

An informal analytical report will identify a problem, provide factual information about the problem, and draw conclusions about the information. An informal report is usually structured like an essay, with an introduction or summary, body paragraphs, and a conclusion or recommendations. It will likely feature headings identifying key sections and be presented in academic essay format, such as APA Documentation and Format. For an example of an informal analytical report documented in APA style, see Trevor Garcia’s paper on the U.S. response to COVID-19 in 2020 in the Annotated Student Sample.

Other types of informal reports include journalism reports. A traditional journalism report involves a reporter for a news organization reporting on the day’s events—the results of an election, a political crisis, a plane crash, a celebrity marriage—on TV, on radio, or in print. An investigative journalism report, on the other hand, involves reporters doing original research over a period of weeks or months to uncover significant new information, similar to what Barbara Ehrenreich did for her book Nickel and Dimed. For sample traditional and investigative journalistic reports, visit the website of a reliable news organization or publication, such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, the New Yorker, or the Atlantic.

Formal Reports

Writers in the social sciences, the natural sciences, technical fields, and business often write formal analytical reports. These include lab reports, research reports, and proposals.

Formal reports present findings and data drawn from experiments, surveys, and research and often end with a conclusion based on an analysis of these findings and data. These reports frequently include visuals such as graphs, bar charts, pie charts, photographs, or diagrams that are captioned and referred to in the text. Formal reports always cite sources of information, often using APA Documentation and Format, used in the examples in this chapter, or a similar style.

If you are assigned a formal report in a class, follow the instructions carefully. Your instructor will likely explain the assignment in detail and provide explicit directions and guidelines for the research you will need to do (including any permission required by your college or university if you conduct research on human subjects), how to organize the information you gather, and how to write and format your report. A formal report is a complex, highly organized, and often lengthy document with a specified format and sections usually marked by headings.

Following are the components of a formal analytical report. Depending on the assignment and the audience, a formal report you write may include some or all of these parts. For example, a research report following APA format usually includes a title page, an abstract, headings for components of the body of the report (methods, results, discussion), and a references page. Detailed APA guidelines are available online, including at the Purdue University Online Writing Lab.

Components of Formal Analytical Reports

Letter of transmittal. When a report is submitted, it is usually accompanied by a letter or email to the recipient explaining the nature of the report and signed by those responsible for writing it. Write the letter of transmittal when the report is finished and ready for submission.

Title page. The title page includes the title of the report, the name(s) of the author(s), and the date it was written or submitted. The report title should describe the report simply, directly, and clearly and should not try to be too clever. For example, The New Student Writing Project: A Two-Year Report is a clear, descriptive title, whereas Write On, Students! is not.

Acknowledgments. If other people and/or organizations contributed to the report, include a page or paragraph thanking them.

Table of contents. For long reports (10 pages or more), create a table of contents to help readers navigate easily. List the major components and subsections of the report and the pages on which they begin.

Executive summary or abstract. The executive summary or abstract is a paragraph that highlights the findings of the report. The purpose of this section is to present information in the quickest, most concentrated, and most economical way possible to be useful to readers. Write this section after you have completed the rest of the report.

Introduction or background. The introduction provides necessary background information to help readers understand the report. This section also indicates what information is included in the report.

Methods. Especially in the social sciences, the natural sciences, and technical disciplines, the methods or procedures section outlines how you gathered information and from what sources, such as experiments, surveys, library research, interviews, and so on.

Results. In the results section, you summarize the data you have collected from your research, explain your method of analysis, and present this information in detail, often in a table, graph, or chart.

Discussion or Conclusion. In this section, you interpret the results and present the conclusions of your research. This section also may be called “Discussion of Findings.”

Recommendations. In this section, you explain what you believe should be done in response to your research findings.

References and bibliography. The references section includes every source you cited in the report. The bibliography contains, in addition to those cited in the report, sources that readers can consult to learn more.

Appendix. An appendix (plural: appendices) includes documents that are related to the report or contain information that can be culled but are not deemed central to understanding the report.

The following links take you to sample formal reports written by students and offer tips from librarians posted by colleges and universities in the United States. These samples may help you better understand what is involved in writing a formal analytical report.

Product review report, from the University/College Library of Broward College and Florida Atlantic University

Business report, from Wright State University

Technical report, from the University of Utah

Lab report, from Hamilton College

Field report, from the University of Southern California

Exploring the Genre

The following are key terms and characteristics related to reports.

Audience: Readers of a report or any piece of writing.

Bias: A preconceived opinion about something, such as a subject, an idea, a person, or a group of people. As a reader, be attentive to potential bias in sources; as a writer, be attentive to your own biases.

Body: The main part of a report between the introduction and the conclusion. The body of an analytical report consists of paragraphs in which the writer presents and analyzes key information.

Citation of sources: References in the written text to sources that a writer has used in a report.

Conclusion and/or recommendation: The last part of a report. In this section, the writer summarizes the significance of the information in the report or offers recommendations—or both.

Critical thinking: The ability to look beneath the surface of words and images to analyze, interpret, and evaluate them.

Ethos: The sense that the writer or other authority is trustworthy and credible; also known as ethical appeal.

Evidence: Statements of fact, statistics, examples, and expert opinions that support the writer’s points.

Facts: Statements whose truth can be proved or verified and that serve as evidence in a report.

Introduction: The first section of a report after any front matter, such as an abstract or table of contents. In an analytical report, the writer introduces the topic to be addressed and often presents the thesis at the end of the introduction.

Logos: The use of facts as evidence to appeal to an audience’s logical and rational thinking; also known as logical appeal.

Objective stance: Writing in a way that is free from bias, personal feelings, and emotional language. An objective stance is especially important in report writing.

Purpose: The reason for writing. The purpose of an analytical report is to examine a subject or issue closely, often from multiple perspectives, by looking at causes and effects, by comparing and contrasting, or by examining problems and proposing solutions.

Statistics: Factual statements that include numbers and often serve as evidence in a report.

Synthesis: Making connections among and combining ideas, facts, statistics, and other information.

Thesis: The central or main idea that you will convey in your report. The thesis is often referred to as the central claim in argumentative writing.

Thesis statement: A declarative sentence (sometimes two) that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic you will cover. For a report, a thesis indicates and limits the scope of the report.

Chapter Description

Discusses local and local revision, provides some techniques, discusses peer feedback and how to construct group feedback, introduces reverse outlining and cutting "fluff'

Just as a mason uses bricks to build sturdy homes, writers use words to build successful documents. Consider the construction of a building. Builders need to use tough, reliable materials to build a solid and structurally sound skyscraper. From the foundation to the roof and every floor in between, every part is necessary. Writers need to use strong, meaningful words from the first sentence to the last and in every sentence in between.

You already know many words that you use every day as part of your writing and speaking vocabulary. You probably also know that certain words fit better in certain situations. Letters, e-mails, and even quickly jotted grocery lists require the proper selection of vocabulary. Imagine you are writing a grocery list to purchase the ingredients for a recipe but accidentally write down cilantro when the recipe calls for parsley. Even though cilantro and parsley look remarkably alike, each produces a very different effect in food. This seemingly small error could radically alter the flavor of your dish!

Having a solid everyday vocabulary will help you while writing, but learning new words and avoiding common word errors will make a real impression on your readers. Experienced writers know that deliberate, careful word selection and usage can lead to more polished, more meaningful work. This chapter covers word choice and vocabulary-building strategies that will improve your writing.

2. Spelling

3. Word choice

1. Commonly confused words

Some words in English cause trouble for speakers and writers because these words share a similar pronunciation, meaning, or spelling with another word. These words are called commonly confused words.

For example, read aloud the following sentences containing the commonly confused words new and knew:

I liked her new sweater.

I knew she would wear that sweater today.

These words may sound alike when spoken, but they carry entirely different usages and meanings. New is an adjective that describes the sweater, and knew is the past tense of the verb to know.

Recognizing Commonly Confused Words

New and knew are just two of the words that can be confusing because of their similarities. Familiarize yourself with the following list of commonly confused words. Recognizing these words in your own writing and in other pieces of writing can help you choose the correct word.

Commonly Confused Words

A, An, And

- A (article). Used before a word that begins with a consonant.

- a key, a mouse, a screen

- An (article). Used before a word that begins with a vowel.

- an airplane, an ocean, an igloo

- And (conjunction). Connects two or more words together.

- peanut butter and jelly, pen and pencil, jump and shout

Accept, Except

- Accept (verb). Means to take or agree to something offered.

- They accepted our proposal for the conference.

- Except (conjunction). Means only or but.

- We could fly there except the tickets cost too much.

Affect, Effect

- Affect (verb). Means to create a change.

- Hurricane winds affect the amount of rainfall.

- Effect (noun). Means an outcome or result.

- The heavy rains will have an effect on the crop growth.

Are, Our

- Are (verb). A conjugated form of the verb be.

- My cousins are all tall and blonde.

- Our (pronoun). Indicates possession, usually follows the pronoun we.

- We will bring our cameras to take pictures.

By, Buy

- By (preposition). Means next to.

- My glasses are by the bed.

- Buy (verb). Means to purchase.

- I will buy new glasses after the doctor’s appointment.

Its, It’s

- Its (pronoun). A form of it that shows possession.

- The butterfly flapped its wings.

- It’s (contraction). Joins the words it and is.

- It’s the most beautiful butterfly I have ever seen.

Know, No

- Know (verb). Means to understand or possess knowledge.

- I know the male peacock sports the brilliant feathers.

- No. Used to make a negative.

- I have no time to visit the zoo this weekend.

Loose, Lose

- Loose (adjective). Describes something that is not tight or is detached.

- Without a belt, her pants are loose on her waist.

- Lose (verb). Means to forget, to give up, or to fail to earn something.

- She will lose even more weight after finishing the marathon training.

Of, Have

- Of (preposition). Means from or about.

- I studied maps of the city to know where to rent a new apartment.

- Have (verb). Means to possess something.

- I have many friends to help me move.

- Have (linking verb). Used to connect verbs.

- I should have helped her with that heavy box.

Quite, Quiet, Quit

- Quite (adverb). Means really or truly.

- My work will require quite a lot of concentration.

- Quiet (adjective). Means not loud.

- I need a quiet room to complete the assignments.

- Quit (verb). Means to stop or to end.

- I will quit when I am hungry for dinner.

Right, Write

- Right (adjective). Means proper or correct.

- When bowling, she practices the right form.

- Right (adjective). Also means the opposite of left.

- Begin the dance with your right foot.

- Write (verb). Means to communicate on paper.

- After the team members bowl, I will write down their scores.

Set, Sit

- Set (verb). Means to put an item down.

- She set the mug on the saucer.

- Set (noun). Means a group of similar objects.

- All the mugs and saucers belonged in a set.

- Sit (verb). Means to lower oneself down on a chair or another place

- I’ll sit on the sofa while she brews the tea.

Suppose, Supposed

- Suppose (verb). Means to think or to consider

- I suppose I will bake the bread because no one else has the recipe.

- Suppose (verb). Means to suggest.

- Suppose we all split the cost of the dinner.

- Supposed (verb). The past tense form of the verb suppose, meaning required or allowed.

- She was supposed to create the menu.

Than, Then

- Than (conjunction). Used to connect two or more items when comparing

- Registered nurses require less schooling than doctors.

- Then (adverb). Means next or at a specific time.

- Doctors first complete medical school and then obtain a residency.

Their, They’re, There

- Their (pronoun). A form of they that shows possession.

- The dog walkers feeds their dogs every day at two o’clock.

- They’re (contraction). Joins the words they and are.

- They’re the sweetest dogs in the neighborhood.

- There (adverb). Indicates a particular place.

- The dogs’ bowls are over there, next to the pantry.

- There (expletive used to delay the subject). Indicates the presence of something

- There are more treats if the dogs behave.

To, Two, Too

- To (preposition). Indicates movement.

- Let’s go to the circus.

- To. A word that completes an infinitive verb.

- to play, to ride, to watch.

- Two. The number after one. It describes how many.

- Two clowns squirted the elephants with water.

- Too (adverb). Means also or very.

- The tents were too loud, and we left.

Use, Used

- Use (verb). Means to apply for some purpose.

- We use a weed whacker to trim the hedges.

- Used. The past tense form of the verb to use

- He used the lawnmower last night before it rained.

- Used to. Indicates something done in the past but not in the present

- He used to hire a team to landscape, but now he landscapes alone.

Who’s, Whose

- Who’s (contraction). Joins the words who and either is or has.

- Who’s the new student? Who’s met him?

- Whose (pronoun). A form of who that shows possession.

- Whose schedule allows them to take the new student on a campus tour?

Your, You’re

- Your (pronoun). A form of you that shows possession.

- Your book bag is unzipped.

- You’re (contraction). Joins the words you and are.

- You’re the girl with the unzipped book bag.

Figure 10.1 "Camera Sign"

The English language contains so many words; no one can say for certain how many words exist. In fact, many words in English are borrowed from other languages. Many words have multiple meanings and forms, further expanding the immeasurable number of English words. Although the list of commonly confused words serves as a helpful guide, even these words may have more meanings than shown here. When in doubt, consult an expert: the dictionary!

Exercise 1

Complete the following sentences by selecting the correct word.

1. My little cousin turns ________(to, too, two) years old tomorrow.

2. The next-door neighbor’s dog is ________(quite, quiet, quit) loud. He barks constantly throughout the night.

3. ________(Your, You’re) mother called this morning to talk about the party.

4. I would rather eat a slice of chocolate cake ________(than, then) eat a chocolate muffin.

5. Before the meeting, he drank a cup of coffee and ________(than, then) brushed his teeth.

6. Do you have any ________(loose, lose) change to pay the parking meter?

7. Father must ________(have, of) left his briefcase at the office.

8. Before playing ice hockey, I was ________(suppose, supposed) to read the contract, but I only skimmed it and signed my name quickly, which may ________(affect, effect) my understanding of the rules.

9. Tonight she will ________(set, sit) down and ________(right, write) a cover letter to accompany her résumé and job application.

10. It must be fall, because the leaves ________(are, our) changing, and ________(it’s, its) getting darker earlier.

Strategies to Avoid Commonly Confused Words

When writing, you need to choose the correct word according to its spelling and meaning in the context. Not only does selecting the correct word improve your vocabulary and your writing, but it also makes a good impression on your readers. It also helps reduce confusion and improve clarity. The following strategies can help you avoid misusing confusing words.

1. Use a dictionary. Keep a dictionary at your desk while you write. Look up words when you are uncertain of their meanings or spellings. Many dictionaries are also available online, and the Internet’s easy access will not slow you down. Check out your cell phone or smartphone to see if a dictionary app is available.

2. Keep a list of words you commonly confuse. Be aware of the words that often confuse you. When you notice a pattern of confusing words, keep a list nearby, and consult the list as you write. Check the list again before you submit an assignment to your instructor.

3. Study the list of commonly confused words. You may not yet know which words confuse you, but before you sit down to write, study the words on the list. Prepare your mind for working with words by reviewing the commonly confused words identified in this chapter.

Figure 10.2 " A Commonly Misused Word on a Public Sign"

Tip

Commonly confused words appear in many locations, not just at work or at school. Be on the lookout for misused words wherever you find yourself throughout the day. Make a mental note of the error and remember its correction for your own pieces of writing.

Exercise 2

The following paragraph contains eleven errors. Find each misused word and correct it by adding the proper word.