Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Discusses the elements that shape an essay

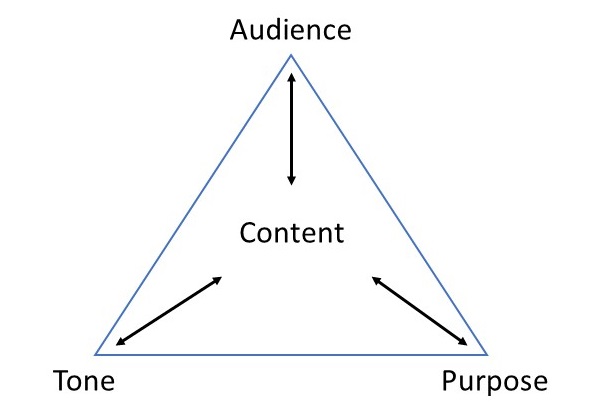

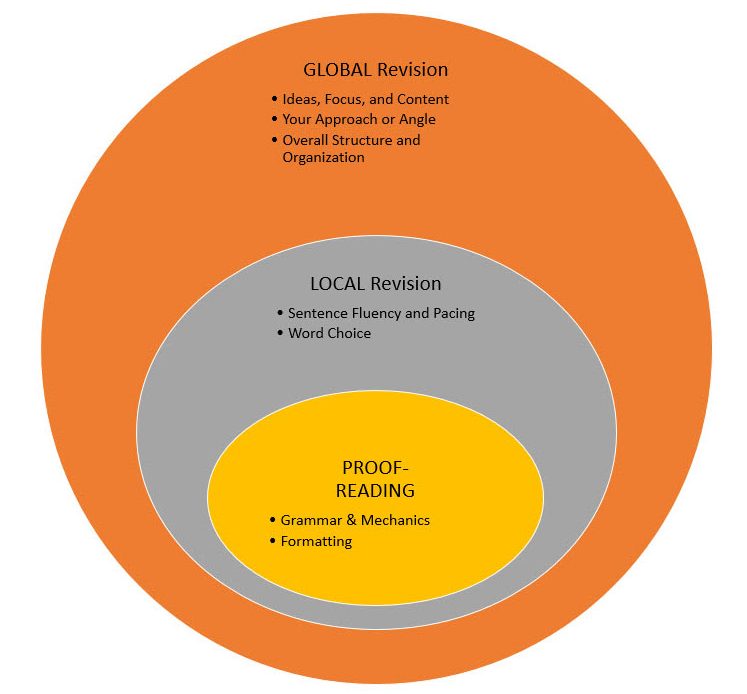

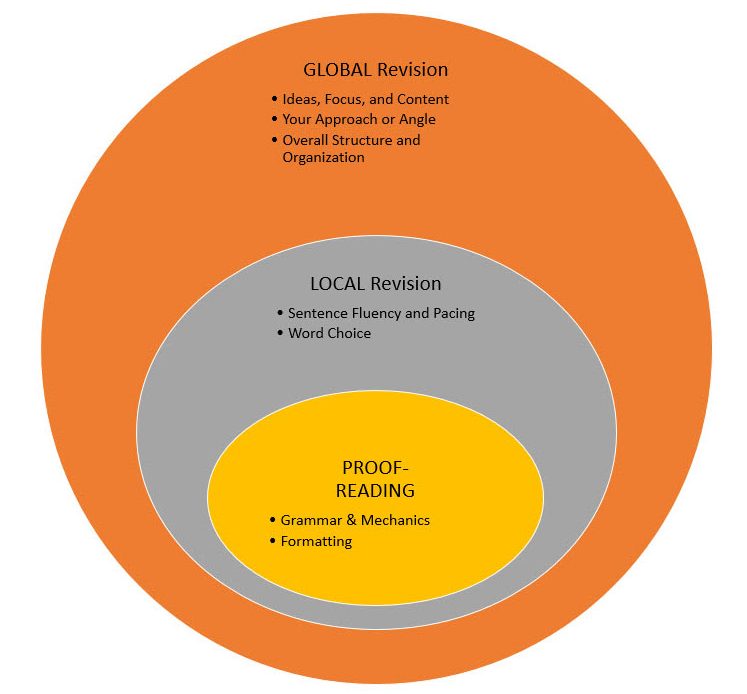

Once you have determined the assignment parameters, it’s time to begin drafting. While doing so, it is important to remain focused on your topic and thesis in order to guide your reader through the essay. Imagine reading one long block of text with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay (see Figure 2.4.1).[1]

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point or thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to classify

- to analyze

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A classification shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials, using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a classification should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document without quoting the original text. Keep in mind that classification moves beyond simple summary to be informative.

An analysis, on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis, instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing—synthesis—combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of classifying, analysis, and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to classify, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about the audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions. For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Example A

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think I caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Example B

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with the intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own essays, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject.

Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience might not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on your intended audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

Demographics

These measure important data about a group of people such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

Education

Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

Prior Knowledge

This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

Expectations

These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit a range of attitudes and emotions through prose–from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers convey their attitudes and feelings with useful devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Exercise

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

“Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just seven percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelts and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.”

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. When applied to that audience of third graders, you would choose simple content that the audience would easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone.

The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Practice Activity

[h5p id=”6″]

Practice Activity

[h5p id=”7″]

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition. 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711203012/https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/

- “The Rhetorical Triangle” was derived by Brandi Gomez from an image in: Kathryn Crowther et al., Successful College Composition, 2nd ed. Book 8. (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

Chapter Description

Discusses local and local revision, provides some techniques, discusses peer feedback and how to construct group feedback, introduces reverse outlining and cutting "fluff'

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

Discusses how to reflect on and write about composing processes

Introduction

Reflecting on your work is an important step in your growth as a writer. Reflection allows you to recognize the ways in which you have mastered some skills and have addressed instances when your intention and execution fail to match. By recognizing previous challenges and applying learned strategies for addressing them, you demonstrate improvement and progress as a writer. This kind of reflection is an example of recursive. At this point in the semester, you know that writing is a recursive process: you prewrite, you write, you revise, you edit, you reflect, you revise, and so on. In working through a writing assignment, you learn and understand more about particular sections of your draft, and you can go back and revise them. The ability to return to your writing and exercise objectivity and honesty about it is one of skills you have practiced during this journey. You are now able to evaluate your own work, accept another’s critique of your writing, and make meaningful revisions.

In this chapter, you will review your work from earlier chapters and write a reflection that captures your growth, feelings, and challenges as a writer. In your reflection, you will apply many of the writing, reasoning, and evidentiary strategies you have already used in other papers—for example, analysis, evaluation, comparison and contrast, problem and solution, cause and effect, examples, and anecdotes.

When looking at your earlier work, you may find that you cringe at those papers and wonder what you were thinking when you wrote them. If given that same assignment, you now would know how to produce a more polished paper. This response is common and is evidence that you have learned quite a bit about writing.

14.1 Thinking Critically about Your Semester

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Reflect on and write about the development of composing processes and how those processes affect your work.

- Demonstrate honesty and objectivity in reflecting on written work.

You have written your way through a long semester, and the journey is nearly complete. Now is the time to step back and reflect on what you have written, what you have mastered, what skill gaps remain, and what you will do to continue growing and improving as a communicator. This reflection will be based on the work you have done and what you have learned during the semester. Because the subject of this reflection is you and your work, no further research is required. The information you need is in the work you have done in this course and in your head. Now, you will work to organize and transfer this information to an organized written text. Every assignment you have completed provides you with insight into your writing process as you think about the assignment’s purpose, its execution, and your learning along the way. The skill of reflection requires you to be critical and honest about your habits, feelings, skills, and writing. In the end, you will discover that you have made progress as a writer, perhaps in ways not yet obvious.

14.2 Glance at Genre: Purpose and Structure

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify conventions of reflection regarding structure, paragraphing, and tone.

- Articulate how genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of technologies and modalities.

Reflective writing is the practice of thinking about an event, an experience, a memory, or something imagined and expressing its larger meaning in written form. Reflective writing comes from the author’s specific perspective and often contemplates the way an event (or something else) has affected or even changed the author’s life.

Areas of Exploration

When you write a reflective piece, consider three main areas of exploration as shown in Figure 14.3. The first is the happening. This area consists of the events included in the reflection. For example, you will be examining writing assignments from this course. As you describe the assignments, you also establish context for the reflection so that readers can understand the circumstances involved. For each assignment, ask yourself these questions: What was the assignment? How did I approach the assignment? What did I do to start this assignment? What did I think about the assignment? If you think of other questions, use them. Record your answers because they will prove useful in the second area.

The second area is reflection. When you reflect on the happening, you go beyond simply writing about the specific details of the assignment; you move into the writing process and an explanation of what you learned from doing the work. In addition, you might recognize—and note—a change in your skills or way of thinking. Ask yourself these questions: What works effectively in this text? What did I learn from this assignment? How is this assignment useful? How did I feel when I was working on this assignment? Again, you can create other questions, and note your responses because you will use them to write a reflection.

The third area is action. Here, you decide what to do next and plan the steps needed to reach that goal. Ask yourself: What does (and does not) work effectively in this text? How can I continue to improve in this area? What should I do now? What has changed in my thinking? How would I change my approach to this assignment if I had to do another one like it? Base your responses to these questions on what you have learned, and implement these elements in your writing.

Figure 14.3 Elements of reflective writing (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Format of Reflective Writing

Unlike thesis statements, which often come at the beginning of an essay, the main point of a piece of reflective writing may be conveyed only indirectly and nearly always emerges at the end, almost like an epiphany, or sudden realization. With this structure, readers are drawn into the act of reflecting and become more curious about what the writer is thinking and feeling. ln other words, reflective writers are musing, exploring, or wondering rather than arguing. In fact, reflective essays are most enlightening when they are not obviously instructive or assertive. However, even though reflective writing does not present an explicit argument, it still includes evidence and cohesion and provides lessons to be learned. As such, elements of persuasion or argument often appear in reflective essays.

Discovery through Writing

Keep in mind, too, that when you start to reflect on your growth as a writer, you may not realize what caused you to explore a particular memory. In other words, writers may choose to explore an idea, such as why something got their attention, and only by recalling the details of that event do they discover the reason it first drew their attention.

When you tell the story of your writing journey this semester, you may find that more was on your mind than you realized. The writing itself is one thing, but the meaning of what you learned becomes something else, and you may deliberately share how that second level, or deeper meaning or feeling, emerged through the act of storytelling. For example, in narrating a writing experience, you may step back, pause, and let readers know, “Wait a minute, something else is going on here.” An explanation of the new understanding, for both you and your readers, can follow this statement. Such pauses are a sign that connections are being made—between the present and the past, the concrete and the abstract, the literal and the symbolic. They signal to readers that the essay or story is about to move in a new and less predictable direction. Yet each idea remains connected through the structure of happenings, reflections, and actions.

Sometimes, slight shifts in voice or tone accompany reflective pauses as a writer moves closer to what is really on their mind. The exact nature of these shifts will, of course, be determined by the writer’s viewpoint. Perhaps one idea that you, as the writer, come up with is the realization that writing a position argument was useful in your history class. You were able to focus more on the material than on how to write the paper because you already knew how to craft a position argument. As you work through this process, continue to note these important little discoveries.

Your Writing Portfolio

As you recall, each chapter in this book has included one or more assignments for a writing portfolio. In simplest terms, a writing portfolio is a collection of your writing contained within a single binder or folder. A portfolio may contain printed copy, or it may be completely digital. Its contents may have been created over a number of weeks, months, or even years, and it may be organized chronologically, thematically, or qualitatively. A portfolio assigned for a class will contain written work to be shared with an audience to demonstrate your writing, learning, and skill progression. This kind of writing portfolio, accumulated during a college course, presents a record of your work over a semester and may be used to assign a grade. Many instructors now offer the option of, or even require, digital multimodal portfolios, which include visuals, audio, and/or video in addition to written texts. Your instructor will provide guidelines on how to create a multimodal portfolio, if applicable. You can also learn more about creating a multimodal portfolio and view one by a first-year student.

Key Terms

As you begin crafting your reflection, consider these elements of reflective writing.

Analysis: When you analyze your own writing, you explain your reasoning or writing choices, thus showing that you understand your progress as a writer.

Context: The context is the circumstances or situation in which the happening occurred. A description of the assignment, an explanation of why it was given, and any other relevant conditions surrounding it would be its context.

Description: Providing specific details, using figurative language and imagery, and even quoting from your papers helps readers visualize and thus share your reflection. When describing, writers may include visuals if applicable.

Evaluation: An effective evaluation points out where you faltered and where you did well. With that understanding, you have a basis to return to your thoughts and speculate about progress you will continue to make in the future.

Observation: Observation is a close look at the writing choices you made and the way you managed the rhetorical situations you encountered. When observing, be objective, and pay attention to the more and less effective parts of your writing.

Purpose: By considering the goals of these previous assignments, you will be better equipped to look at them critically and objectively to understand their larger use in academia.

Speculation: Speculation encourages you to think about your next steps: where you need to improve and where you need to stay sharp to avoid recurring mistakes.

Thoughts: Your thoughts (and feelings) before, during, and after an assignment can provide you with descriptive material. In a reflective essay, writers may choose to indicate their thoughts in a different tense from the one in which they write the essay itself.

When you put these elements together, you will be able to reflect objectively on your own writing. This reflection might include identifying areas of significant improvement and areas that still need more work. In either case, focus on describing, analyzing, and evaluating how and why you did or did not improve. This is not an easy task for any writer, but it proves valuable for those who aim to improve their skills as communicators.

What Is Audience?

Knowing and addressing an audience is one of the components of the rhetorical situation (the author, the setting, the purpose, the text, and the audience).

Think about the last time you wrote a paper; who were you writing to? It is likely that you assumed you were writing to the teacher, so you may have focused on writing “correctly” rather than exploring who you were really trying to address and how that should affect your style, language, tone, evidence, etc.

Now, think about the last time you posted on Facebook or crafted a Tweet. It is likely that you were hyper-aware of your audience and how what you posted or shared might affect your audience. Knowing that you already have experience(s) with audience expectations when posting or creating social media texts should help you understand how important knowing your audience is when writing in the college composition classroom.

Types of Audience

Writing to an Imagined Audience

When writing, especially in college classes, you might be asked to write for an “imagined” audience, which can be difficult for any writer, but specifically for emerging writers. As stated by Melanie Gagich below:

Invoking an audience requires students to imagine and construct their audience, and can be difficult for emerging or even practiced writers. Even when writing instructors do provide students with a specific audience within a writing assignment, it is probable that this “audience” will likely be conceptualized by the student as his or her teacher. This “writing to the teacher” frame of mind often results in students guessing how to address their audience, which hinders their ability to write academically.

Thinking of audience as someone or a group beyond the teacher will help you see various ways you can use language, evidence, style, etc. to support your message and to help you build credibility as the writer/creator. Consider, for example, that your claim seeks to change a law. Are you writing to voters, perhaps a group of peers who might support your position, or are you writing to lawmakers, who will be speaking the legalese (the formal and technical language of legal documents) of those who amend the law? For each of the separate audiences (your group of voting peers versus lawmakers), you might adopt a different tone and approach in your writing.

Writing to a Real Audience

You may also be called upon to address a real and interactive audience. For instance, if your instructor asks you to write an entry for Wikipedia, create a multimodal text, or present your work to your peers; then, the audience is not imagined but concrete and able to “talk back.” Writing for real audience members can be difficult, especially online audiences, because “we can’t always know in advance who they are” (NCTE), yet writing to these audience members can also be a helpful experience because they can respond to your work and offer feedback that goes beyond a teacher’s evaluative responses. Composing in 21st-century spaces makes interacting with, talking back to, and learning from audience members much easier.

Addressing an interactive audience also gives you the opportunity to embrace diversity through the act of sharing your work digitally and to explore what it means to be rhetorically aware. Being rhetorically aware means that you understand how the integration of various language(s), cultural references/experiences, linguistic text, images, sounds, documentation style, etc. can help you form a cohesive and logical message that is carefully shared with an interactive audience in an appropriate online space.

What Are Discourse Communities?

Knowing the type of audience you’re being asked to address is the first step to becoming aware of your audience. The second step is to determine whether the audience you’re addressing are members of a discourse community. According to NCTE, a discourse community is “a group of people, members of a community, who share a common interest and who use the same language, or discourse, as they talk and write about that interest.” Though you may not address a discourse community every time you write, when you are asked to address an academic audience, you are addressing a discourse community.

Generally, everyone is a member of a discourse community. For example, members of movie trivia sites, video gamers, sports fans, etc. are all examples of discourse community membership. Members can often distinguish each other based on their use (or misuse) of language, jargon, slang, symbols, media, clothing, and more. In academia, discourse communities are connected to academic disciplines. For instance, a literature professor’s interests may be very different from a social science professor’s. Differences will also be evident in their use of documentation styles, manuscript formatting, the language they use, and the journals they submit their work to.

You may wonder why it matters. Why not just write in MLA all the time and use the same word choices and tone every time you write? Well, it comes back to illustrating your credibility and awareness of the conventions and communication genres of a discourse community. NCTE explains, “When we write it is useful to think in terms of the discourse community we are participating in and whose members we are addressing: what do they assume, what kinds of questions do they ask, and what counts as evidence?” You earn credibility when discussing a basketball team’s performance when you know all the names of the team members. In a different context, you also demonstrate credibility when you know to use APA rather than MLA in various academic contexts.

Furthermore, consider the previous example of a claim seeking to alter a law. The language one uses to inspire one’s peers to civic action might be significantly more casual than the language used to change the opinion of those who are in charge of altering laws. The age, cultural background, education, and profession of your audience might affect your writing.

Attributions: Melanie Gagich is the original author of this section and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

It has been further edited and original content by Dr. Adam Falik and Dr. Doreen Piano for the LOUIS OER Dual Enrollment course development program to create "English Composition II" and has been licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Content Description

Discusses how to reflect on write about the development

Introduction

Reflecting on your work is an important step in your growth as a writer. Reflection allows you to recognize the ways in which you have mastered some skills and have addressed instances when your intention and execution fail to match. By recognizing previous challenges and applying learned strategies for addressing them, you demonstrate improvement and progress as a writer. This kind of reflection is an example of recursive. At this point in the semester, you know that writing is a recursive process: you prewrite, you write, you revise, you edit, you reflect, you revise, and so on. In working through a writing assignment, you learn and understand more about particular sections of your draft, and you can go back and revise them. The ability to return to your writing and exercise objectivity and honesty about it is one of skills you have practiced during this journey. You are now able to evaluate your own work, accept another’s critique of your writing, and make meaningful revisions.

In this chapter, you will review your work from earlier chapters and write a reflection that captures your growth, feelings, and challenges as a writer. In your reflection, you will apply many of the writing, reasoning, and evidentiary strategies you have already used in other papers—for example, analysis, evaluation, comparison and contrast, problem and solution, cause and effect, examples, and anecdotes.

When looking at your earlier work, you may find that you cringe at those papers and wonder what you were thinking when you wrote them. If given that same assignment, you now would know how to produce a more polished paper. This response is common and is evidence that you have learned quite a bit about writing.

14.1 Thinking Critically about Your Semester

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Reflect on and write about the development of composing processes and how those processes affect your work.

- Demonstrate honesty and objectivity in reflecting on written work.

You have written your way through a long semester, and the journey is nearly complete. Now is the time to step back and reflect on what you have written, what you have mastered, what skill gaps remain, and what you will do to continue growing and improving as a communicator. This reflection will be based on the work you have done and what you have learned during the semester. Because the subject of this reflection is you and your work, no further research is required. The information you need is in the work you have done in this course and in your head. Now, you will work to organize and transfer this information to an organized written text. Every assignment you have completed provides you with insight into your writing process as you think about the assignment’s purpose, its execution, and your learning along the way. The skill of reflection requires you to be critical and honest about your habits, feelings, skills, and writing. In the end, you will discover that you have made progress as a writer, perhaps in ways not yet obvious.

14.2 Glance at Genre: Purpose and Structure

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify conventions of reflection regarding structure, paragraphing, and tone.

- Articulate how genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of technologies and modalities.

Reflective writing is the practice of thinking about an event, an experience, a memory, or something imagined and expressing its larger meaning in written form. Reflective writing comes from the author’s specific perspective and often contemplates the way an event (or something else) has affected or even changed the author’s life.

Areas of Exploration

When you write a reflective piece, consider three main areas of exploration as shown in Figure 14.3. The first is the happening. This area consists of the events included in the reflection. For example, you will be examining writing assignments from this course. As you describe the assignments, you also establish context for the reflection so that readers can understand the circumstances involved. For each assignment, ask yourself these questions: What was the assignment? How did I approach the assignment? What did I do to start this assignment? What did I think about the assignment? If you think of other questions, use them. Record your answers because they will prove useful in the second area.

The second area is reflection. When you reflect on the happening, you go beyond simply writing about the specific details of the assignment; you move into the writing process and an explanation of what you learned from doing the work. In addition, you might recognize—and note—a change in your skills or way of thinking. Ask yourself these questions: What works effectively in this text? What did I learn from this assignment? How is this assignment useful? How did I feel when I was working on this assignment? Again, you can create other questions, and note your responses because you will use them to write a reflection.

The third area is action. Here, you decide what to do next and plan the steps needed to reach that goal. Ask yourself: What does (and does not) work effectively in this text? How can I continue to improve in this area? What should I do now? What has changed in my thinking? How would I change my approach to this assignment if I had to do another one like it? Base your responses to these questions on what you have learned, and implement these elements in your writing.

Figure 14.3 Elements of reflective writing (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Format of Reflective Writing

Unlike thesis statements, which often come at the beginning of an essay, the main point of a piece of reflective writing may be conveyed only indirectly and nearly always emerges at the end, almost like an epiphany, or sudden realization. With this structure, readers are drawn into the act of reflecting and become more curious about what the writer is thinking and feeling. ln other words, reflective writers are musing, exploring, or wondering rather than arguing. In fact, reflective essays are most enlightening when they are not obviously instructive or assertive. However, even though reflective writing does not present an explicit argument, it still includes evidence and cohesion and provides lessons to be learned. As such, elements of persuasion or argument often appear in reflective essays.

Discovery through Writing

Keep in mind, too, that when you start to reflect on your growth as a writer, you may not realize what caused you to explore a particular memory. In other words, writers may choose to explore an idea, such as why something got their attention, and only by recalling the details of that event do they discover the reason it first drew their attention.

When you tell the story of your writing journey this semester, you may find that more was on your mind than you realized. The writing itself is one thing, but the meaning of what you learned becomes something else, and you may deliberately share how that second level, or deeper meaning or feeling, emerged through the act of storytelling. For example, in narrating a writing experience, you may step back, pause, and let readers know, “Wait a minute, something else is going on here.” An explanation of the new understanding, for both you and your readers, can follow this statement. Such pauses are a sign that connections are being made—between the present and the past, the concrete and the abstract, the literal and the symbolic. They signal to readers that the essay or story is about to move in a new and less predictable direction. Yet each idea remains connected through the structure of happenings, reflections, and actions.

Sometimes, slight shifts in voice or tone accompany reflective pauses as a writer moves closer to what is really on their mind. The exact nature of these shifts will, of course, be determined by the writer’s viewpoint. Perhaps one idea that you, as the writer, come up with is the realization that writing a position argument was useful in your history class. You were able to focus more on the material than on how to write the paper because you already knew how to craft a position argument. As you work through this process, continue to note these important little discoveries.

Your Writing Portfolio

As you recall, each chapter in this book has included one or more assignments for a writing portfolio. In simplest terms, a writing portfolio is a collection of your writing contained within a single binder or folder. A portfolio may contain printed copy, or it may be completely digital. Its contents may have been created over a number of weeks, months, or even years, and it may be organized chronologically, thematically, or qualitatively. A portfolio assigned for a class will contain written work to be shared with an audience to demonstrate your writing, learning, and skill progression. This kind of writing portfolio, accumulated during a college course, presents a record of your work over a semester and may be used to assign a grade. Many instructors now offer the option of, or even require, digital multimodal portfolios, which include visuals, audio, and/or video in addition to written texts. Your instructor will provide guidelines on how to create a multimodal portfolio, if applicable. You can also learn more about creating a multimodal portfolio and view one by a first-year student.

Key Terms

As you begin crafting your reflection, consider these elements of reflective writing.

Analysis: When you analyze your own writing, you explain your reasoning or writing choices, thus showing that you understand your progress as a writer.

Context: The context is the circumstances or situation in which the happening occurred. A description of the assignment, an explanation of why it was given, and any other relevant conditions surrounding it would be its context.

Description: Providing specific details, using figurative language and imagery, and even quoting from your papers helps readers visualize and thus share your reflection. When describing, writers may include visuals if applicable.

Evaluation: An effective evaluation points out where you faltered and where you did well. With that understanding, you have a basis to return to your thoughts and speculate about progress you will continue to make in the future.

Observation: Observation is a close look at the writing choices you made and the way you managed the rhetorical situations you encountered. When observing, be objective, and pay attention to the more and less effective parts of your writing.

Purpose: By considering the goals of these previous assignments, you will be better equipped to look at them critically and objectively to understand their larger use in academia.

Speculation: Speculation encourages you to think about your next steps: where you need to improve and where you need to stay sharp to avoid recurring mistakes.

Thoughts: Your thoughts (and feelings) before, during, and after an assignment can provide you with descriptive material. In a reflective essay, writers may choose to indicate their thoughts in a different tense from the one in which they write the essay itself.

When you put these elements together, you will be able to reflect objectively on your own writing. This reflection might include identifying areas of significant improvement and areas that still need more work. In either case, focus on describing, analyzing, and evaluating how and why you did or did not improve. This is not an easy task for any writer, but it proves valuable for those who aim to improve their skills as communicators.

Chapter Description

Discusses local and local revision, provides some techniques, discusses peer feedback and how to construct group feedba

Introduction

Reflecting on your work is an important step in your growth as a writer. Reflection allows you to recognize the ways in which you have mastered some skills and have addressed instances when your intention and execution fail to match. By recognizing previous challenges and applying learned strategies for addressing them, you demonstrate improvement and progress as a writer. This kind of reflection is an example of recursive. At this point in the semester, you know that writing is a recursive process: you prewrite, you write, you revise, you edit, you reflect, you revise, and so on. In working through a writing assignment, you learn and understand more about particular sections of your draft, and you can go back and revise them. The ability to return to your writing and exercise objectivity and honesty about it is one of skills you have practiced during this journey. You are now able to evaluate your own work, accept another’s critique of your writing, and make meaningful revisions.

In this chapter, you will review your work from earlier chapters and write a reflection that captures your growth, feelings, and challenges as a writer. In your reflection, you will apply many of the writing, reasoning, and evidentiary strategies you have already used in other papers—for example, analysis, evaluation, comparison and contrast, problem and solution, cause and effect, examples, and anecdotes.

When looking at your earlier work, you may find that you cringe at those papers and wonder what you were thinking when you wrote them. If given that same assignment, you now would know how to produce a more polished paper. This response is common and is evidence that you have learned quite a bit about writing.

14.1 Thinking Critically about Your Semester

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Reflect on and write about the development of composing processes and how those processes affect your work.

- Demonstrate honesty and objectivity in reflecting on written work.

You have written your way through a long semester, and the journey is nearly complete. Now is the time to step back and reflect on what you have written, what you have mastered, what skill gaps remain, and what you will do to continue growing and improving as a communicator. This reflection will be based on the work you have done and what you have learned during the semester. Because the subject of this reflection is you and your work, no further research is required. The information you need is in the work you have done in this course and in your head. Now, you will work to organize and transfer this information to an organized written text. Every assignment you have completed provides you with insight into your writing process as you think about the assignment’s purpose, its execution, and your learning along the way. The skill of reflection requires you to be critical and honest about your habits, feelings, skills, and writing. In the end, you will discover that you have made progress as a writer, perhaps in ways not yet obvious.

14.2 Glance at Genre: Purpose and Structure

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify conventions of reflection regarding structure, paragraphing, and tone.

- Articulate how genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of technologies and modalities.

Reflective writing is the practice of thinking about an event, an experience, a memory, or something imagined and expressing its larger meaning in written form. Reflective writing comes from the author’s specific perspective and often contemplates the way an event (or something else) has affected or even changed the author’s life.

Areas of Exploration

When you write a reflective piece, consider three main areas of exploration as shown in Figure 14.3. The first is the happening. This area consists of the events included in the reflection. For example, you will be examining writing assignments from this course. As you describe the assignments, you also establish context for the reflection so that readers can understand the circumstances involved. For each assignment, ask yourself these questions: What was the assignment? How did I approach the assignment? What did I do to start this assignment? What did I think about the assignment? If you think of other questions, use them. Record your answers because they will prove useful in the second area.

The second area is reflection. When you reflect on the happening, you go beyond simply writing about the specific details of the assignment; you move into the writing process and an explanation of what you learned from doing the work. In addition, you might recognize—and note—a change in your skills or way of thinking. Ask yourself these questions: What works effectively in this text? What did I learn from this assignment? How is this assignment useful? How did I feel when I was working on this assignment? Again, you can create other questions, and note your responses because you will use them to write a reflection.

The third area is action. Here, you decide what to do next and plan the steps needed to reach that goal. Ask yourself: What does (and does not) work effectively in this text? How can I continue to improve in this area? What should I do now? What has changed in my thinking? How would I change my approach to this assignment if I had to do another one like it? Base your responses to these questions on what you have learned, and implement these elements in your writing.

Figure 14.3 Elements of reflective writing (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Format of Reflective Writing

Unlike thesis statements, which often come at the beginning of an essay, the main point of a piece of reflective writing may be conveyed only indirectly and nearly always emerges at the end, almost like an epiphany, or sudden realization. With this structure, readers are drawn into the act of reflecting and become more curious about what the writer is thinking and feeling. ln other words, reflective writers are musing, exploring, or wondering rather than arguing. In fact, reflective essays are most enlightening when they are not obviously instructive or assertive. However, even though reflective writing does not present an explicit argument, it still includes evidence and cohesion and provides lessons to be learned. As such, elements of persuasion or argument often appear in reflective essays.

Discovery through Writing

Keep in mind, too, that when you start to reflect on your growth as a writer, you may not realize what caused you to explore a particular memory. In other words, writers may choose to explore an idea, such as why something got their attention, and only by recalling the details of that event do they discover the reason it first drew their attention.

When you tell the story of your writing journey this semester, you may find that more was on your mind than you realized. The writing itself is one thing, but the meaning of what you learned becomes something else, and you may deliberately share how that second level, or deeper meaning or feeling, emerged through the act of storytelling. For example, in narrating a writing experience, you may step back, pause, and let readers know, “Wait a minute, something else is going on here.” An explanation of the new understanding, for both you and your readers, can follow this statement. Such pauses are a sign that connections are being made—between the present and the past, the concrete and the abstract, the literal and the symbolic. They signal to readers that the essay or story is about to move in a new and less predictable direction. Yet each idea remains connected through the structure of happenings, reflections, and actions.

Sometimes, slight shifts in voice or tone accompany reflective pauses as a writer moves closer to what is really on their mind. The exact nature of these shifts will, of course, be determined by the writer’s viewpoint. Perhaps one idea that you, as the writer, come up with is the realization that writing a position argument was useful in your history class. You were able to focus more on the material than on how to write the paper because you already knew how to craft a position argument. As you work through this process, continue to note these important little discoveries.

Your Writing Portfolio

As you recall, each chapter in this book has included one or more assignments for a writing portfolio. In simplest terms, a writing portfolio is a collection of your writing contained within a single binder or folder. A portfolio may contain printed copy, or it may be completely digital. Its contents may have been created over a number of weeks, months, or even years, and it may be organized chronologically, thematically, or qualitatively. A portfolio assigned for a class will contain written work to be shared with an audience to demonstrate your writing, learning, and skill progression. This kind of writing portfolio, accumulated during a college course, presents a record of your work over a semester and may be used to assign a grade. Many instructors now offer the option of, or even require, digital multimodal portfolios, which include visuals, audio, and/or video in addition to written texts. Your instructor will provide guidelines on how to create a multimodal portfolio, if applicable. You can also learn more about creating a multimodal portfolio and view one by a first-year student.

Key Terms

As you begin crafting your reflection, consider these elements of reflective writing.

Analysis: When you analyze your own writing, you explain your reasoning or writing choices, thus showing that you understand your progress as a writer.

Context: The context is the circumstances or situation in which the happening occurred. A description of the assignment, an explanation of why it was given, and any other relevant conditions surrounding it would be its context.

Description: Providing specific details, using figurative language and imagery, and even quoting from your papers helps readers visualize and thus share your reflection. When describing, writers may include visuals if applicable.

Evaluation: An effective evaluation points out where you faltered and where you did well. With that understanding, you have a basis to return to your thoughts and speculate about progress you will continue to make in the future.

Observation: Observation is a close look at the writing choices you made and the way you managed the rhetorical situations you encountered. When observing, be objective, and pay attention to the more and less effective parts of your writing.

Purpose: By considering the goals of these previous assignments, you will be better equipped to look at them critically and objectively to understand their larger use in academia.

Speculation: Speculation encourages you to think about your next steps: where you need to improve and where you need to stay sharp to avoid recurring mistakes.

Thoughts: Your thoughts (and feelings) before, during, and after an assignment can provide you with descriptive material. In a reflective essay, writers may choose to indicate their thoughts in a different tense from the one in which they write the essay itself.

When you put these elements together, you will be able to reflect objectively on your own writing. This reflection might include identifying areas of significant improvement and areas that still need more work. In either case, focus on describing, analyzing, and evaluating how and why you did or did not improve. This is not an easy task for any writer, but it proves valuable for those who aim to improve their skills as communicators.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Discusses local and global revision and how to construct group feedback

- Global revision exercise for a narrative essay

- Includes tips for doing a reverse outline with a student example, a global revision exercise (for a narrative essay), and strategies for eliminating "fluff"

Concepts and Strategies for Revision

Let’s start with a few definitions. What is an essay? It’s likely that your teachers have been asking you to write essays for years now; you’ve probably formed some idea of the genre. But when I ask my students to define this kind of writing, their answers vary widely and only get at part of the meaning of “essay.”

Although we typically talk of an essay (noun), I find it instructive to think about essay (verb): to try, to test, to explore, to attempt to understand. An essay (noun), then, is an attempt and an exploration. Popularized shortly before the Enlightenment era by Michel de Montaigne, the essay form was invested in the notion that writing invites discovery: the idea was that he, as a layperson without formal education in a specific discipline, would learn more about a subject through the act of writing itself.

What difference does this new definition make for us as writers?

- Writing invites discovery.

- Throughout the act of writing, you will learn more about your topic. Even though some people think of writing as a way to capture a fully formed idea, writing can also be a way to process ideas—in other words, writing can be an act of thinking. It forces you to look closer and see more. Your revisions should reflect the knowledge you gain through the act of writing.

- An essay is an attempt, but not all attempts are successful on the first try.

- You should give yourself license to fail, to an extent. If to essay is to try, then it’s OK to fall short. Writing is also an iterative process, which means your first draft isn’t the final product.

Now, what is revision? You may have been taught that revision means fixing commas, using a thesaurus to brighten up word choice, and maybe tweaking a sentence or two. However, I prefer to think of revision as “re | vision.”

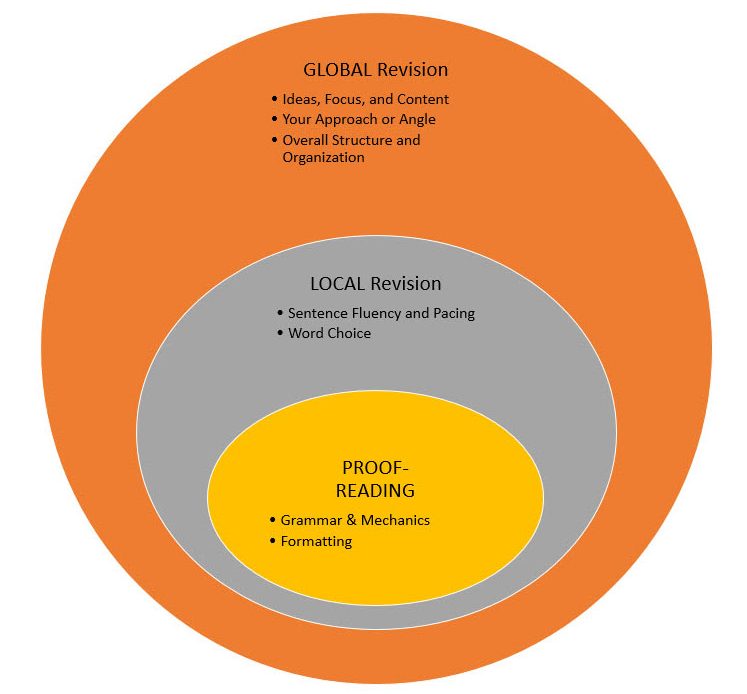

Revision isn’t just about polishing—it’s about seeing your piece from a new angle, with “fresh eyes.” Often, we get so close to our own writing that we need to be able to see it from a different perspective in order to improve it. Revision happens on many levels. What you may have been trained to think of as revision—grammatical and mechanical fixes—is just one tier. Here’s how I like to imagine it:

Even though all kinds of revision are valuable, your global issues are first-order concerns, and proofreading is a last-order concern. If your entire topic, approach, or structure needs revision, it doesn’t matter if you have a comma splice or two. It’s likely that you’ll end up rewriting that sentence anyway.

There are a handful of techniques you can experiment with in order to practice true revision. First, if you can, take some time away from your writing. When you return, you will have a clearer head. You will even, in some ways, be a different person when you come back—since we as humans are constantly changing from moment to moment, day to day, you will have a different perspective with some time away. This might be one way for you to make procrastination work in your favor: if you know you struggle with procrastination, try to bust out a quick first draft the day an essay is assigned. Then you can come back to it a few hours or a few days later with fresh eyes and a clearer idea of your goals.

Second, you can challenge yourself to reimagine your writing using global and local revision techniques, like those included later in this chapter.

Third, you can (and should) read your paper aloud, if only to yourself. This technique distances you from your writing; by forcing yourself to read aloud, you may catch sticky spots, mechanical errors, abrupt transitions, and other mistakes you would miss if you were immersed in your writing. (Recently, a student shared with me that she uses an online text-to-speech voice reader to create this same separation. By listening along and taking notes, she can identify opportunities for local- and proofreading-level revision.)

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, you should rely on your learning community. Because you most likely work on tight deadlines and don’t always have the opportunity to take time away from our projects, you should solicit feedback from your classmates, the writing center, your instructor, your peer workshop group, or your friends and family. As readers, they have valuable insight into the rhetorical efficacy of your writing: their feedback can be useful in developing a piece that is conscious of audience. To begin setting expectations and procedures for your peer workshop, turn to the first activity in this section.

Throughout this text, I have emphasized that good writing cannot exist in a vacuum; similarly, good rewriting often requires a supportive learning community. Even if you have had negative experiences with peer workshops before, I encourage you to give them another chance. Not only do professional writers consistently work with other writers, but my students are nearly always surprised by just how helpful it is to work alongside their classmates.

The previous diagram (of global, local, and proofreading levels of revision) reminds us that everyone has something valuable to offer in a learning community: because there are so many different elements on which to articulate feedback, you can provide meaningful feedback to your workshop, even if you don’t feel like an expert writer.

During the many iterations of revising, remember to be flexible and to listen. Seeing your writing with fresh eyes requires you to step outside of yourself, figuratively.

Listen actively and seek to truly understand feedback by asking clarifying questions and asking for examples. The reactions of your audience are a part of writing that you cannot overlook, so revision ought to be driven by the responses of your colleagues.

On the other hand, remember that the ultimate choice to use or disregard feedback is at the author’s discretion: provide all the suggestions you want as a group member, but use your best judgment as an author. If members of your group disagree—great! Contradictory feedback reminds us that writing is a dynamic, transactional action that is dependent on the specific rhetorical audience.

| Vocabulary | Definition |

|---|---|

| Essay | A medium, typically nonfiction, by which an author can achieve a variety of purposes. Popularized by Michel de Montaigne as a method of discovery of knowledge: in the original French, essay is a verb that means “to try, to test, to explore, to attempt to understand.” |

| Fluff | Uneconomical writing: filler language or unnecessarily wordy phrasing. Although fluff occurs in a variety of ways, it can be generally defined as words, phrases, sentences, or paragraphs that do not work hard to help you achieve your rhetorical purpose. |

| Iterative | Literally a repetition within a process. The writing process is iterative because it is nonlinear and because an author often has to repeat, revisit, or reapproach different steps along the way. |

| Learning community | A network of learners and teachers, each equipped and empowered to provide support through horizontal power relations. Values diversity insofar as it encourages growth and perspective but also inclusivity. Also, a community that learns by adapting to its unique needs and advantages. |

| Revision | The iterative process of changing a piece of writing. Literally revision: seeing your writing with “fresh eyes” in order to improve it. Includes changes on global, local, and proofreading levels. Changes might include the following:

|

Revision Activities

Establishing Your Peer Workshop

Before you begin working with a group, it’s important for you to establish a set of shared goals, expectations, and processes. You might spend a few minutes talking through the following questions:

- Have you ever participated in a peer workshop before? What worked? What didn’t?

- What do you hate about group projects? How might you mitigate these issues?

- What opportunities do group projects offer that working independently doesn’t? What are you excited about?

- What requests do you have for your peer workshop group members?

In addition to thinking through the culture you want to create for your workshop group, you should also consider the kind of feedback you want to exchange, practically speaking. In order to arrive at a shared definition for “good feedback,” I often ask my students to complete the following sentence as many times as possible with their groupmates: “Good feedback is…”

The list could go on forever, but here are a few that I emphasize:

| “Good feedback is…” | ||

|---|---|---|

| Kind | Actionable | Not prescriptive (offers suggestions, not demands) |

| Cognizant of process (i.e., recognizes that a first draft isn’t a final draft) | Respectful | Honest |

| Specific | Comprehensive (i.e., global, local, and proofreading) | Attentive |

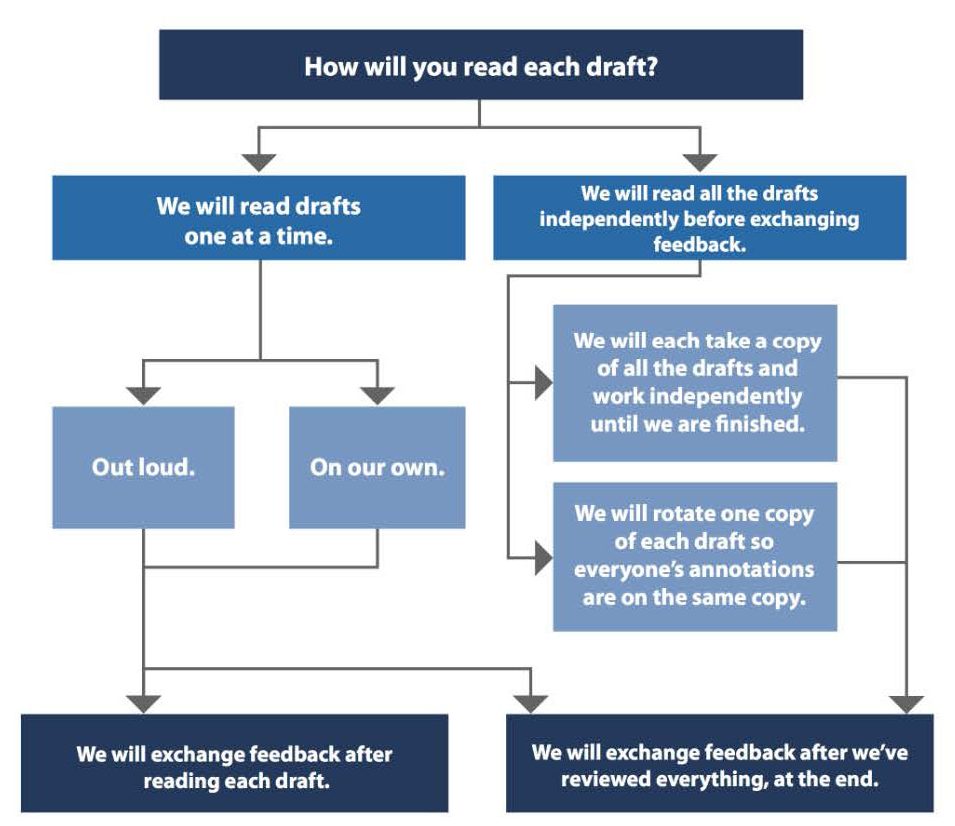

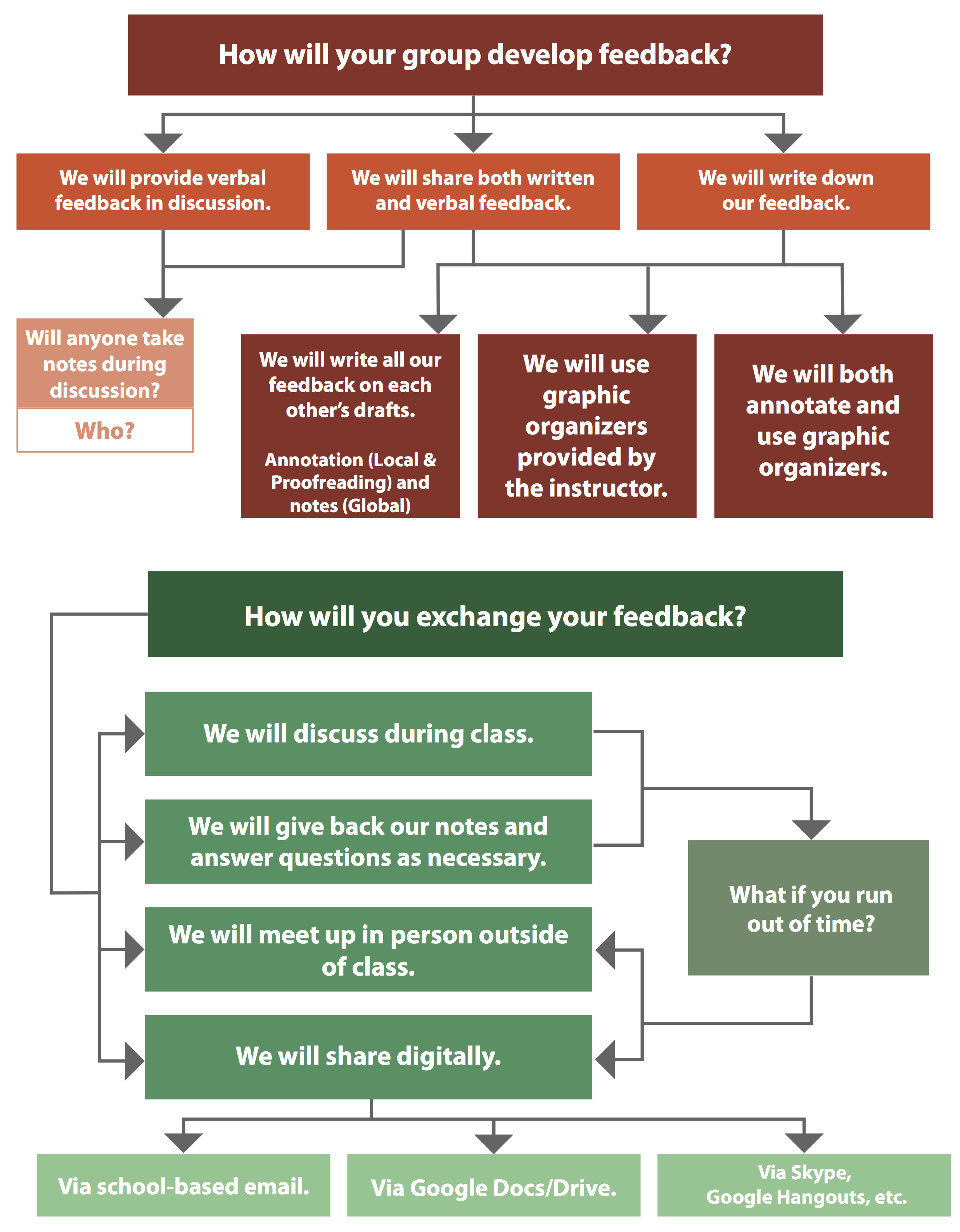

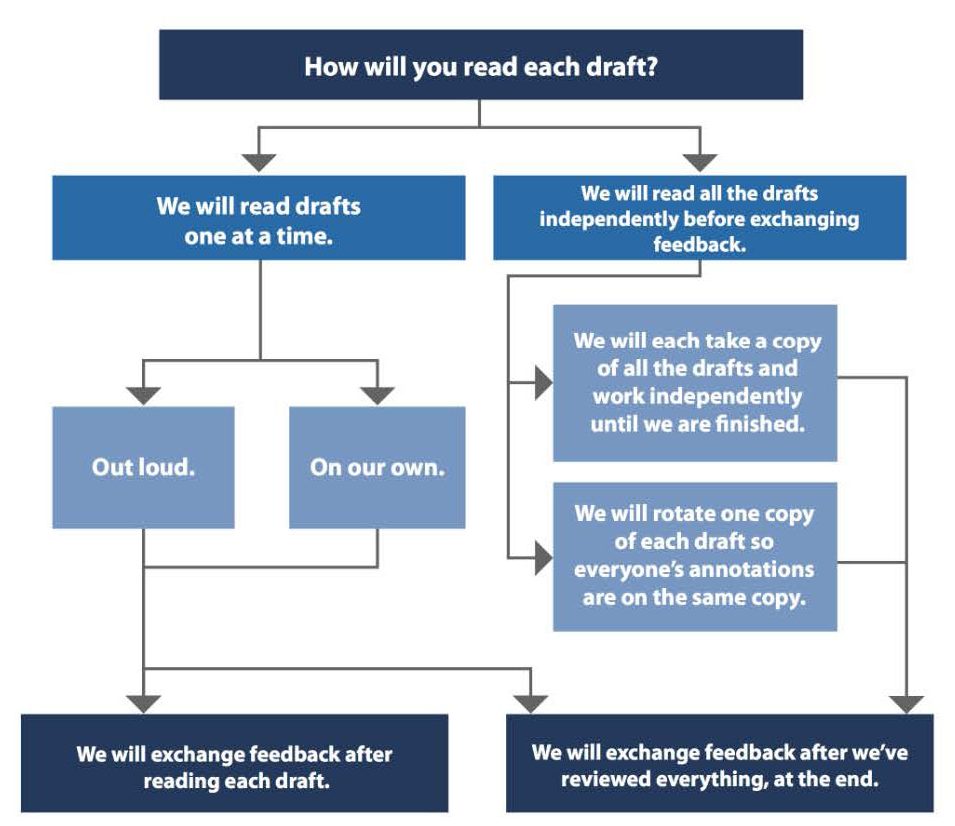

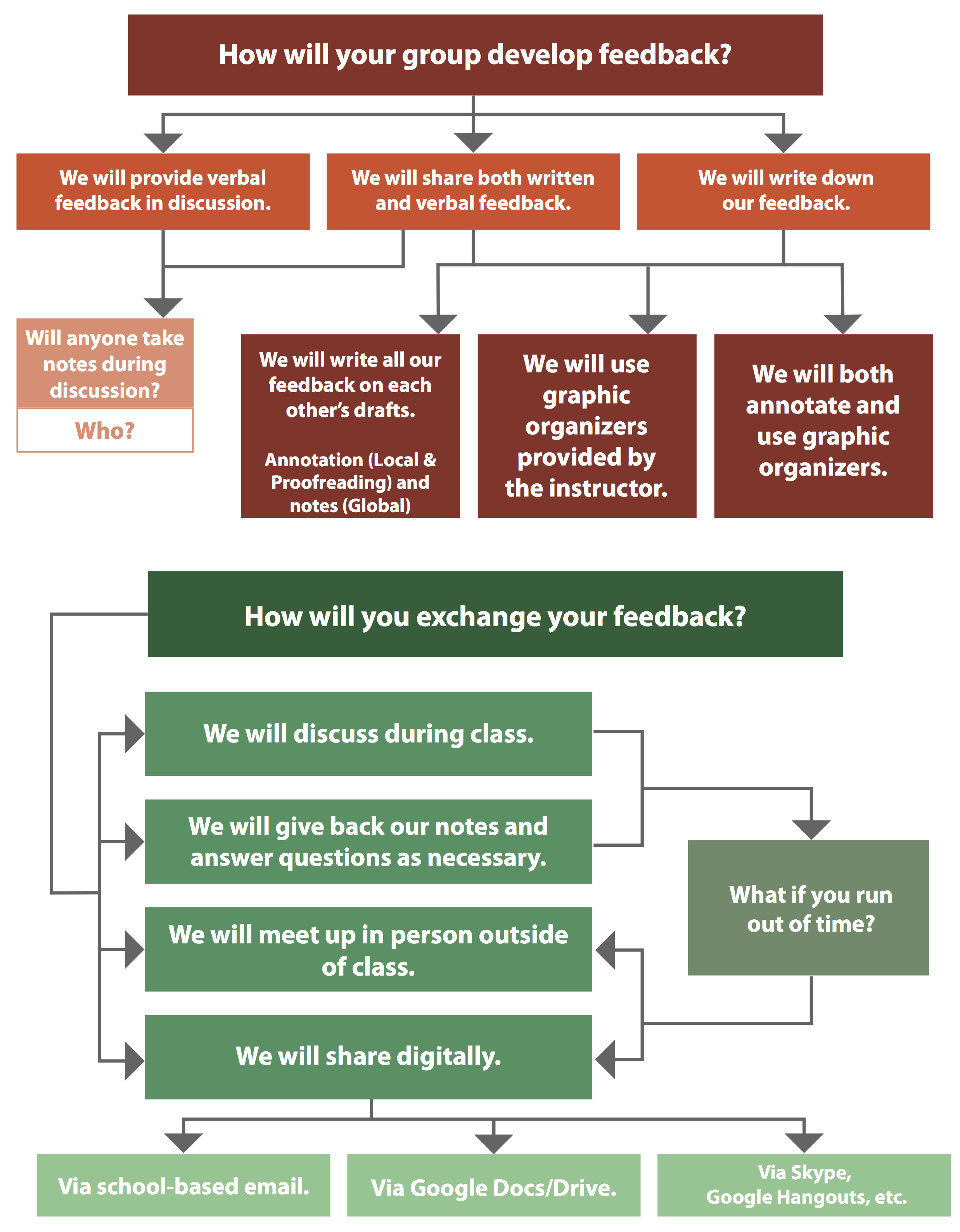

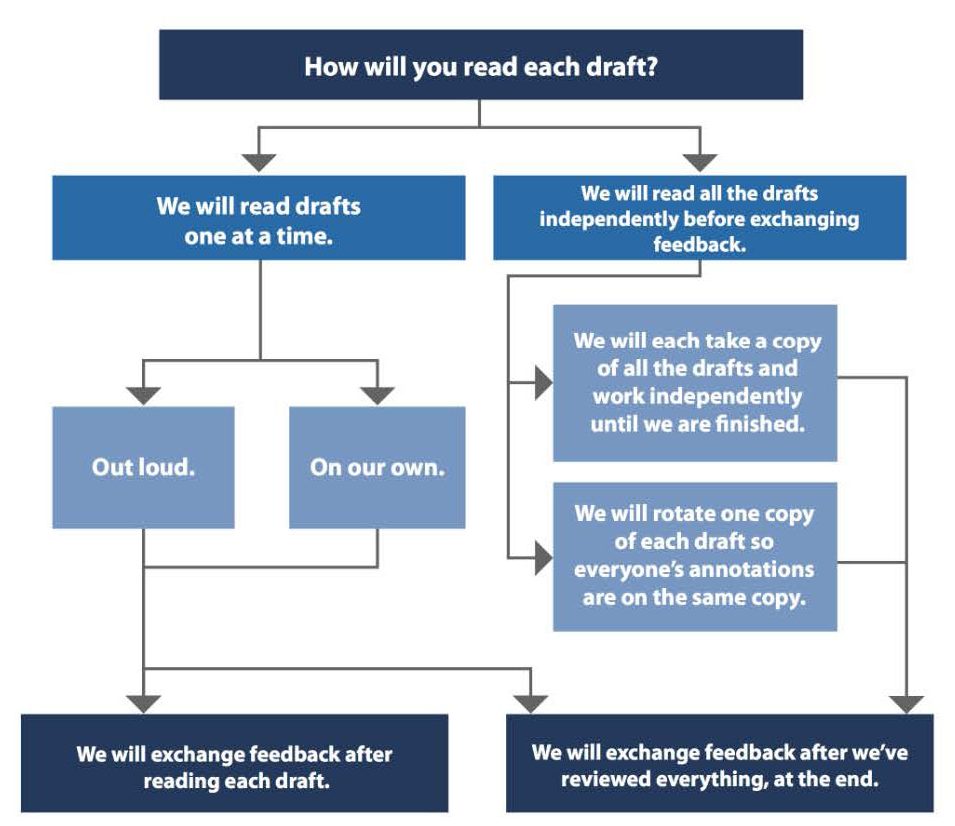

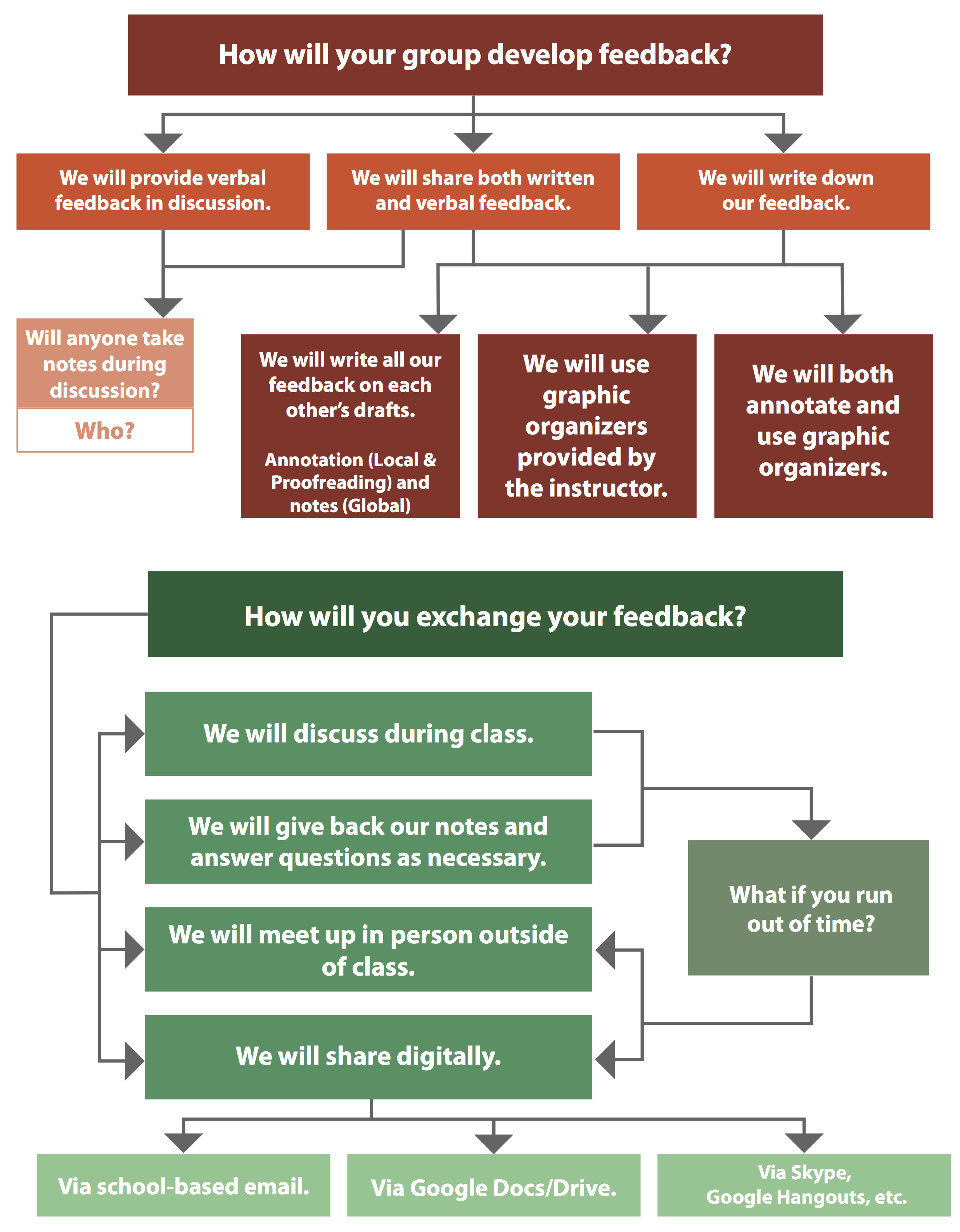

Once you’ve discussed the parameters for the learning community you’re building, you can begin workshopping your drafts, asking, “What does the author do well and what could they do better?” Personally, I prefer a workshop that’s conversational, allowing the author and the audience to discuss the work both generally and specifically; however, your group should use whatever format will be most valuable for you. Before starting your workshop, try to get everyone on the same page logistically by using the following flowcharts.

To set the tone and expectations for your unique workshop group, talk through the following prompts. Record your answers. The first activity will establish a climate or culture for your group; the second will help you talk through logistics.

Choose the 3-5 descriptors of good feedback that are most important to the members of your group. Discuss for 3-5 minutes: What do each of you need for this Peer Workshop to be effective? From each other? From the instructor? From yourselves? From your environment? Record responses on a separate sheet of paper.

Global Revision Activity for a Narrative Essay

This assignment challenges you to try new approaches to a draft you’ve already written. Although you will be “rewriting” in this exercise, you are not abandoning your earlier draft: this exercise is generative, meaning it is designed to help you produce new details, ideas, or surprising bits of language that you might integrate into your project.

First, choose a part of your draft that (1) you really like but think could be better or (2) just isn’t working for you. This excerpt should be no fewer than one hundred words and can include your entire essay, if you want.

Then complete your choice of one prompt from the list below: apply the instruction to the excerpt to create new content. Read over your original once, but do not refer back to it after you start writing. Your goal here is to deviate from the first version, not reproduce it. The idea here is to produce something new about your topic through constraint; you are reimagining your excerpt on a global scale.

After completing one prompt, go back to the original and try at least one more or apply a different prompt to your new work.

- Change genres. For example, if your excerpt is written in typical essay form, try writing it as poetry, or dialogue from a play/movie, or a radio advertisement.

- Zoom in. Focus on one image, color, idea, or word from your excerpt and zoom way in. Meditate on this one thing with as much detail as possible.

- Zoom out. Step back from the excerpt and contextualize it with background information, concurrent events, or information about relationships or feelings.

- Change point of view. Try a new vantage point for your story by changing pronouns and perspective. For instance, if your excerpt is in first person (I/me), switch to second (you) or third person (he/she/they).

- Change setting. Resituate your excerpt in a different place or time.

- Change your audience. Rewrite the excerpt anticipating the expectations of a different reader than you first intended. For example, if the original excerpt is in the same speaking voice you would use with your friends, write as if your strictest teacher or the president or your grandmother is reading it. If you’ve written in an “academic” voice, try writing for your closest friend—use slang, swear words, casual language, whatever.

- Add another voice. Instead of just the speaker of the essay narrating, add a listener. This listener can agree, disagree, question, heckle, sympathize, apologize, or respond in any other way you can imagine.

- Change timeline (narrative sequence). Instead of moving chronologically forward, rearrange the events to bounce around.

- Change tense. Narrate from a different vantage point by changing the grammar. For example, instead of writing in past tense, write in present or future tense.

- Change tone. Reimagine your writing in a different emotional register. For instance, if your writing is predominantly nostalgic, try a bitter tone. If you seem regretful, try to write as if you were proud.

Reverse Outlining

Have you ever written an outline before writing a draft? It can be a useful prewriting strategy, but it doesn’t work for all writers. If you’re like me, you prefer to brain-dump a bunch of ideas on the paper, then come back to organize and refocus during the revision process. One strategy that can help you here is reverse outlining.

Divide a blank piece of paper into three columns, as demonstrated below. Number each paragraph of your draft, and write an equal numbered list down the left column of your blank piece of paper. Write “Idea” at the top of the middle column and “Purpose” at the top of the right column.

| Paragraph Number (¶#) | Idea (What is the ¶ saying?) |

Purpose (What is the ¶ doing?) |

|---|---|---|

| Paragraph 1 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 2 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 3 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 4 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 5 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 6 | Notes: | Notes: |

| Paragraph 7 | Notes: | Notes: |

Now wade back through your essay, identifying what each paragraph is saying and what each paragraph is doing. Choose a few key words or phrases for each column to record on your sheet of paper.

- Try to use consistent language throughout the reverse outline so you can see where your paragraphs are saying or doing similar things.

- A paragraph might have too many different ideas or too many different functions for you to concisely identify. This could be a sign that you need to divide that paragraph up.

Here’s a student’s model reverse outline:

| Paragraph Number (¶) | Idea (What is the ¶ saying?) |

Purpose (What is the ¶ doing?) |

|---|---|---|

| Paragraph 1 | Theater is an important part of education and childhood development. | Setting up and providing thesis statement |

| Paragraph 2 | There have been many changes in recent history to public education in the United States. | Providing context for thesis |

| Paragraph 3 | Theater programs in public schools have been on the decline over the past two decades. | Providing context and giving urgency to the topic |

| Paragraph 4 | a. Theater has social/emotional benefits. b. Theater has academic benefits. |

Supporting and explaining thesis |

| Paragraph 5 | a. Acknowledge argument in favor of standardized testing. b. STEAM curriculum incorporates arts education into other academic subjects. |

Disarming audience, proposing a solution to underfunded arts programs |

| Paragraph 6 | Socioeconomic inequality is also an obstacle to theater education. | Acknowledging broader scope of topic |

| Paragraph 7 | Looking forward at public education reform, we should incorporate theater into public education. | Call to action, backing up and restating thesis |

But wait—there’s more!

Once you have identified the idea(s) and purpose(s) of each paragraph, you can start revising according to your observations. From the completed reverse outline, create a new outline with a different sequence, organization, focus, or balance. You can reorganize by

- combining or dividing paragraphs,

- rearranging ideas, and

- adding or subtracting content.

Reverse outlining can also be helpful in identifying gaps and redundancies: Now that you have a new outline, do any of your ideas seem too brief? Do you need more evidence for a certain argument? Do you see ideas repeated more than necessary?

After completing the reverse outline above, the student proposed this new organization:

| Proposed changes based on reverse outline: |

|---|

| 1 |

| 4a |

| 4b |

| Combine 2 and 5a |

| Combine 3 and 6 |

| 5b |

| Write new paragraph on other solutions |

| 7 |

You might note that this strategy can also be applied on the sentence and section level. Additionally, if you are a kinesthetic or visual learner, you might cut your paper into smaller pieces that you can physically manipulate.

Be sure to read aloud after reverse outlining to look for abrupt transitions.

You can see a simplified version of this technique demonstrated in this video.

Local Revision Activity: Cutting Fluff

When it’s late at night, the deadline is approaching, and we’ve simply run out of things to say…we turn to fluff. Fluff refers to language that doesn’t do work for you—language that simply takes up space or sits flat on the page rather than working economically and impactfully. Whether or not you’ve used it deliberately, all authors have been guilty of fluffy writing at one time or another.

Example of fluff on social media [“Presidents don’t have to be smart” from funnyjunk.com].

Fluff happens for a lot of reasons.

- Of course, reaching a word or page count is the most common motivation.

- Introductions and conclusions are often fluffy because the author can’t find a way into or out of the subject or because the author doesn’t know what their exact subject will be.

- Sometimes, the presence of fluff is an indication that the author doesn’t know enough about the subject or that their scope is too broad.

- Other times, fluffy language is deployed in an effort to sound “smarter” or “fancier” or “more academic”—which is an understandable pitfall for developing writers.

These circumstances, plus others, encourage us to use language that’s not as effective, authentic, or economical. Fluff happens in a lot of ways; here are a few I’ve noticed:

| Fluff's Supervillainous Alter-Ego | Supervillain Origin Story |

|---|---|

| Thesaurus syndrome | A writer uses inappropriately complex language (often because of the right-click “Synonyms” function) to achieve a different tone. The more complex language might be used inaccurately or sound inauthentic because the author isn’t as familiar with it. |

| Roundabout phrasing | Rather than making a direct statement (“That man is a fool.”), the author uses couching language or beats around the bush (“If one takes into account each event, each decision, it would not be unwise for one to suggest that that man’s behaviors are what some would call foolish.”) |

| Abstraction or generalities | If the author hasn’t quite figured out what they want to say or has too broad of a scope, they might discuss an issue very generally without committing to specific, engaging details. |

| Digression | An author might get off topic, accidentally or deliberately, creating extraneous, irrelevant, or unconnected language. |

| Ornamentation or flowery language | Similarly to thesaurus syndrome, often referred to as “purple prose,” an author might choose words that sound pretty or smart but aren’t necessarily the right words for their ideas. |

| Wordy sentences | Even if the sentences an author creates are grammatically correct, they might be wordier than necessary. |

Of course, there’s a very fine line between detail and fluff. Avoiding fluff doesn’t mean always using the fewest words possible. Instead, you should occasionally ask yourself in the revision process, How is this part contributing to the whole? Is this somehow building toward a bigger purpose? If the answer is no, then you need to revise.

The goal should not necessarily be “Don’t write fluff” but rather “Learn to get rid of fluff in revision.” In light of our focus on process, you are allowed to write fluff in the drafting period, so long as you learn to “prune” during revisions. (I use the word prune as an analogy for caring for a plant: just as you must cut the dead leaves off for the plant’s health and growth, you will need to cut fluff so your writing can thrive.)

Here are a few strategies:

- Read out loud.