Using the Right Sources

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Discusses how to choose sources to establish credibility

Types of Evidence in Academic Arguments

All academic writers use evidence to support their claims. However, as writing tasks vary across disciplinary fields, different types of evidence are required. Often a combination of different types of evidence is required in order to adequately support and develop a point.

To clarify, evidence is what a writer uses to support or defend his or her argument, and only valid and credible evidence is enough to make an argument strong.

Evidence is not simply “facts.” Evidence is not simply “quotes.”

As you develop your research-supported essay, consider not only what types of evidence might support your ideas but also what types of evidence will be considered valid or credible according to the academic discipline or academic audience for which you are writing. The following are some examples of credible evidence by academic discipline:

Evidence in the Humanities: Literature, Art, Film, Music, Philosophy

- Scholarly essays that analyze original works;

- Details from an image, a film, or other work of art;

- Passages from a musical composition;

- Passages of text, including poetry.

Evidence in the Humanities: History

- Primary sources (photos, letters, maps, official documents, etc.);

- Other books or articles that interpret primary sources or other evidence.

Evidence in the Social Sciences: Psychology, Sociology, Political Science, Anthropology

- Books or articles that interpret data and results from other people’s original experiments or studies;

- Results from one’s own field research (including interviews, surveys, observations, etc.);

- Data from one’s own experiments;

- Statistics derived from large studies.

Evidence in the Sciences: Biology, Chemistry, Physics

- Data from the author of the paper’s own experiments;

- Books or articles that interpret data and results from other people’s original experiments or studies.

What remains consistent no matter the discipline in which you are writing, however, is that evidence NEVER speaks for itself. Quality evidence must be integrated into your own argument or claim in order to demonstrate that the evidence supports your thesis. In addition, be alert to evidence that seems to contradict your claims or offers a counterargument to it. Rebutting that counter argument can be powerful evidence for your claim. You can also make evidence that isn’t there an integral part of your argument, too. If you can’t find the evidence you think you need, ask yourself why it seems to be lacking, or if its absence adds a new dimension to your thinking about the topic. Remember, evidence is not the piling up of facts or quotes. Evidence is only one component of a strong, well supported, well argued, and well written composition.

Scholarly Sources

While reading academic/scholarly journal articles can be one of the more intimidating aspects of college-level research projects, there are several aspects to the purpose, format, and style of scholarly/academic journal articles that are rather straightforward and patterned. Knowing the template that scholarly articles follow can enhance your reading and comprehension experience and make these intimidating reading materials much less daunting. Moreover, understanding the purpose of scholarly publication can help you to understand what matters most in these articles.

The term scholarly is one that can be quite confusing. Some professors will use it broadly to mean any source that is reputable and academic in nature, while other professors will use it more narrowly to refer specifically to sources that have gone through a peer review process. Generally speaking, sources may fall on a spectrum between popular and scholarly, with peer-reviewed research articles and monographs fitting most clearly under the scholarly category. Always check with your professor to be sure how they are defining scholarly sources for the purposes of your class.

Basic Format

Information in academic journal articles is presented in a formal, highly prescribed format, meaning that scholarly articles tend to follow a similar layout, pattern, and style. The pages often look stark, with little decoration or imagery. We see few photos in scholarly articles. The article title is often fairly prominent on the first page, as are the author(s)’ name(s). Sometimes there is a bit of information about each author, such as the name of his or her current academic institution or academic credentials. At either the top or bottom of the first few pages, you can find the name of the scholarly journal in which the article is published.

Abstract

On the first page of the article, you will often find an abstract, which is a summary of the author’s research question, methods and results. While this abstract is useful to you as a reader because it gives you some background about the article before you begin reading, you should not cite this abstract in your paper. Please read these abstracts as you are initially seeking sources so that you can determine whether or not reading the article will be useful to you, but do not quote or paraphrase from the abstract.

Works Cited

At the end of academic articles, you will find a list of Works Cited (sometimes called a List of References). This is generally quite long, and it details all of the work that the author considered or cited in designing his or her own research project or in writing the article. Helpful hint: reading the Works Cited in an article that you find to be particularly illuminating or useful can be a great way to locate other sources that may be useful for your own research project. If you see a title that looks interesting, see if you can access it via your university’s library.

Literature Review

Scholarly sources often contain Literature Reviews in the beginning section of the article. They are generally several paragraphs or pages long. Some articles are only Literature Reviews. These Literature Reviews generally do not constitute an author’s own work. Instead, they are summaries and syntheses of other scholars’ work that has previously been published on the topic that the author is addressing in his or her paper. Including this review of previous research helps the author to communicate his or her understanding of the context out of which his or her research comes.

Like the abstract, the Literature Review is another part of a scholarly article from which you should generally not quote. Often, students will mistakenly try to cite information that they find in this Literature Review section of scholarly articles. But that is sort of like citing a SparkNotes version of an essay that you have not read. The Literature Review is where your author, in his or her own words, describes previous research. He or she is outlining what others have said in their own articles, not offering his or her own new insight (and what we are interested in in scholarly articles is the new information that a researcher brings to the topic). If you find that there is interesting information from the sources that your author discusses in the Literature Review, then you should locate the article(s) that the author is summarizing and read them for yourself. That, in fact, is a great strategy for finding more sources.

The “Research Gap”

Somewhere near the end of the Literature Review, authors may indicate what has not been said or not been examined by previous scholars. This has been called a “research gap” – a space out of which a scholar’s own research develops. The “research gap” opens the opportunity for the author to assert his or her own research question or claim. Academic authors who want to publish in scholarly research journals need to define a research gap and then attempt to fill that gap because scholarly journals want to publish new, innovative and interesting work that will push knowledge and scholarship in that field forward. Scholars must communicate what new ideas they have worked on: what is their new hypothesis, or experiment, or interpretation or analysis.

The Scholar(s) Add Their New Perspective

Then, and sometimes for the bulk of an academic article, the author discusses their original work and analysis. This is the part of the article where the author(s) add to the conversation, where they try to fill in the research gap that they identified. This is also the part of the article that is the primary research. The author(s) may include a discussion of their research methodology and results, or an elaboration and defense of their reasoning, interpretation or analysis. Scholarly articles in the sciences or social sciences may include headings such as “Methods,” “Results,” and “Discussion” or synonyms of those words in this part of the article. In arts or humanities journal articles, these headings may not appear because scholars in the arts and humanities do not necessarily perform lab-based research in the same way as scientists or social scientists do. Authors may reference others’ research even in this section of original work and analysis, but only to support or enhance the discussion of the scholar’s own discussion. This is the part of the scholarly article that you should cite from, as it indicates the work your author or authors have done.

Conclusion

To conclude a scholarly journal article, authors may reference their original research question or hypothesis once more. They may summarize some of the points made in the article. We often see scholars concluding by indicating how, why, or to whom their research matters. Sometimes, authors will conclude by looking forward, offering ideas for other scholars to engage in future research. Sometimes, they may reflect on why an experiment failed (if it did) and how to approach that experiment differently next time. What we do not tend to see is scholars merely summarizing everything they discussed in the essay, point by point. Instead, they want to leave readers with a sense of why the work that they have discussed in their article matters.

As you read scholarly sources, remember:

- To look for the author’s research question or hypothesis;

- To seek out the “research gap”: why did the author have this research question or hypothesis?

- To identify the Literature Review;

- To identify the point at which the author stops discussing previous research and begins to discuss his or her own;

- Most importantly: remember to always try to understand what new information this article brings to the scholarly “conversation” about this topic?

Types of Sources: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary

The determination of a text as “popular” or “scholarly/academic” is one way to classify it and to understand what type of information you are engaging with. Another way to classify sources is by considering whether they are primary, secondary or tertiary. Popular sources can be primary, secondary, or tertiary. Scholarly sources, also, can be primary, secondary, or tertiary.

What is a Primary Source?

Primary sources are texts that arise directly from a particular event or time period. They may be letters, speeches, works of art, works of literature, diaries, direct personal observations, newspaper articles that offer direct observations of current events, survey responses, tweets, other social media posts, original scholarly research (meaning research that the author or authors conduct themselves) or any other content that comes out of direct involvement with an event or a research study.

Primary research is information that has not yet been critiqued, interpreted or analyzed by a second (or third, etc.) party.

Primary sources can be popular (if published in newspapers, magazines or websites for the general public) or academic (if written by scholars and published in scholarly journals).

Examples of primary sources:

- Journals, diaries

- Blog posts

- A speech

- Data from surveys or polls

- Scholarly journal articles in which the author(s) discuss the methods and results from their own original research/experiments

- Photos, videos, sound recordings

- Interviews or transcripts

- Poems, paintings, sculptures, songs or other works of art

- Government documents (such as reports of legislative sessions, laws or court decisions, financial or economic reports, and more)

What is a Secondary Source?

Secondary sources summarize, interpret, critique, analyze, or offer commentary on primary sources.

In a secondary source, an author’s subject is not necessarily something that he or she directly experienced. The author of a secondary source may be summarizing, interpreting or analyzing data or information from someone else’s research or offering an interpretation or opinion on current events. Thus, the secondary source is one step away from that original, primary topic/subject/research study.

Secondary sources can be popular (if published in newspapers, magazines or websites for the general public) or academic (if written by scholars and published in scholarly journals).

Examples of secondary sources:

- Book, movie or art reviews

- Summaries of the findings from other people’s research

- Interpretations or analyses of primary source materials or other people’s research

- Histories or biographies

- Political commentary

What is a Tertiary Source?

Tertiary sources are syntheses of primary and secondary sources. The person/people who compose a tertiary text are summarizing, compiling, and/or paraphrasing others’ work. These sources sometimes do not list an author.

Tertiary sources can be popular or academic.

Examples of tertiary sources include:

- Encyclopedias

- Fact books

- Dictionaries

- Guides

- Handbooks

- Wikipedia

Thinking about Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources and your Research Strategy

- What kinds of primary sources would be useful for your research project? Why? Where will you find them? Are you more interested in popular primary sources or scholarly primary sources — and why?

- What kinds of secondary sources could be useful for your project – and why? Are you more interested in popular secondary sources or scholarly secondary sources – and why?

- What kinds of tertiary sources might you try to access? In what ways would this tertiary source help you in your research?

Practice Activity

[h5p id=”40″]

This section contains material from:

Jeffrey, Robin, and Yvonne Bruce. “Types of Evidence in Academic Arguments.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/types-of-evidence-in-academic-arguments/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027003610/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/types-of-evidence-in-academic-arguments/

Zickel, Emilie. “A Deeper Look at Scholarly Sources.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/a-deeper-look-at-scholarly-sources/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027013128/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/a-deeper-look-at-scholarly-sources/

“Types of Primary Sources: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/types-of-sources-primary-secondary-tertiary/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027000647/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/types-of-sources-primary-secondary-tertiary/

OER credited in the texts above include:

Jeffrey, Robin. About Writing: A Guide. Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711210756/https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/

Chapter Description

Discusses local and local revision, provides some techniques, discusses peer feedback and how to construct group feedback, introduces reverse outlining and cutting "fluff'

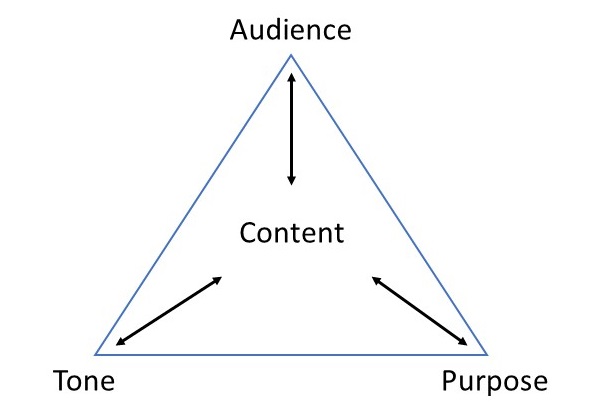

Now that you have determined the assignment parameters, it’s time to begin drafting. While doing so, it is important to remain focused on your topic and thesis in order to guide your reader through the essay. Imagine reading one long block of text with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay (see Figure 2.4.1).[1]

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point or thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to classify

- to analyze

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A classification shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials, using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a classification should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document without quoting the original text. Keep in mind that classification moves beyond simple summary to be informative.

An analysis, on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis, instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing—synthesis—combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of classifying, analysis, and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to classify, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about the audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions. For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Example A

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think I caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Example B

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with the intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own essays, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject.

Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience might not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on your intended audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

Demographics

These measure important data about a group of people such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

Education

Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

Prior Knowledge

This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

Expectations

These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit a range of attitudes and emotions through prose--from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers convey their attitudes and feelings with useful devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Exercise

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

"Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just seven percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelts and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction."

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. When applied to that audience of third graders, you would choose simple content that the audience would easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone.

The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Practice Activity

[h5p id="6"]

Practice Activity

[h5p id="7"]

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition. 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711203012/https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/