Chapter 3: Food Safety

“Each and every member of the food industry, from farm to fork, must create a culture where food safety and nutrition is paramount.”

-Bill Marlar, Foodborne Illness Attorney, Food Safety Advocate

You wake up one morning and feel lousy. You have a headache, feel nauseated, and vomited during the night. Is it the flu? Maybe. Or it could be something you ate yesterday, last week, or last month that is causing your symptoms. In this chapter we will explore the causes of foodborne illness, who is most at risk for severe symptoms, and what can be done to diminish the chances that a food will become contaminated and cause illness.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major types and causes of foodborne illness and contamination.

- Identify groups that are at higher risk for foodborne illness.

- Describe the process government officials use to track foodborne illness.

- Explain the ways food manufacturers reduce the risk of foodborne illness.

- Describe the consumer level techniques for avoiding foodborne illness.

- Discuss nutrition related recommendations for preparing for disasters.

3.1 Foodborne Illness and Food Safety

Foodborne illness is a serious threat to health. Sometimes called “food poisoning,” foodborne illness can result from exposure to a pathogen or a toxin via food or beverages. Food may be contaminated anywhere from “farm to fork.” Raw foods, such as seafood and meat, can be contaminated during harvest or slaughter, processing, packaging, or during distribution, and meat and poultry are among the most common sources of foodborne illness. Fruits and vegetables can be compromised in the fields with contaminated water, or in processing when in contact with contaminated workers. For many foods, contamination can occur during preparation and cooking in a home kitchen or in a restaurant.1 Water can also be a source of foodborne illness, particularly in developing nations.

Annually one out of six (about 17%) Americans become sick after consuming contaminated foods or beverages. Foodborne illness can range from mild stomach upset to more severe symptoms and even fatalities. Most produce mild symptoms and are never reported. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 128,000 require hospitalization and 3,000 die from foodborne illness each year.2

Not only can food contamination be dangerous to your health, it can also be harmful to your wallet. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that foodborne illnesses cost more than $15.6 billion each year.3

At Risk Groups

No one is immune from consuming contaminated food. But whether you become seriously ill depends on the microorganism (pathogen or toxin) causing the illness, the amount you consumed, and your overall health. In addition, some groups have a higher risk than others for developing severe complications to foodborne disease.4 Who is most at risk?

- Young children. Their immune systems are still developing and foodborne illness can be particularly dangerous as the effects of diarrhea and dehydration can be more severe. Children younger than five are three times more likely to be hospitalized than other age groups if they get a Salmonella infection.

- Older adults. Their immune systems and organs may not recognize and get rid of harmful pathogens as well as they once did. Nearly half of those aged 65 and older who have lab-confirmed foodborne illness from Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria or E. coli require hospitalization.

- Pregnant women. Have a higher chance of becoming very sick after consuming contaminated food and this can be particularly harmful for the developing fetus.

- Those with compromised immune systems due to HIV/AIDs, immunosuppressive medications (such as after an organ transplant), diabetes, liver or kidney disease, or receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy. For example, people on dialysis are 50 times more likely to develop severe symptoms from Listeria infection.

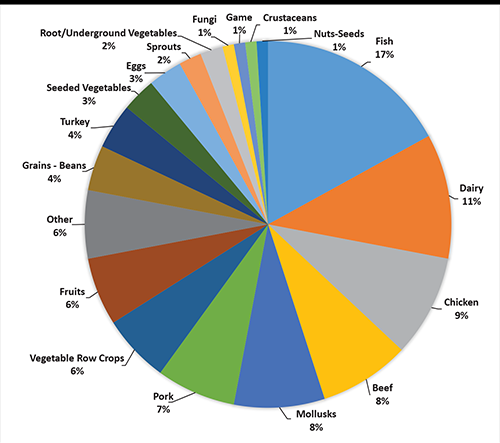

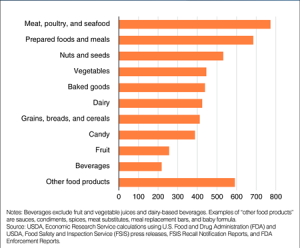

Figure 3.1.2 Total Number of Food Recalls by Food Category

3.2 The Major Types of Foodborne Illness

Foodborne illnesses are either infectious or toxic in nature. The difference depends on the agent that causes the condition. Microbes, such as bacteria, cause food infections, while toxins, such as the kinds produced by molds, or exposure to pollutants can cause food intoxications. Different diseases manifest in different ways, so signs and symptoms can vary with the source of contamination. However the illness occurs, the microbe or toxin enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract, and as a result common symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea. Additional symptoms may include vomiting, dehydration, lightheadedness, and rapid heartbeat. More severe complications can include a high fever, diarrhea/vomiting that lasts more than three days, bloody stools, and signs of shock.

Both food infections and food intoxications can create a burden on health systems when patients require treatment and support and on food systems when companies must recall contaminated food or address public concerns. It all begins with the agent that causes the contamination. When a person ingests a food contaminant, it travels to the stomach and intestines where it can interfere with the body’s functions. In the next part, we will focus on different types of food contaminants and examine common microbes, toxins, chemicals, and other substances that can cause food infections and intoxications.

One of the biggest misconceptions about foodborne illness is that it is always triggered by the last meal that a person ate. Actually it often takes several days or more before the onset of symptoms. The time between exposure to the pathogen and the onset of symptoms is called the incubation period. Incubation periods differ based on the pathogen, the health status of the infected person, and the type of exposure. If you develop a foodborne illness, you should rest and drink plenty of fluids. Avoid antidiarrheal medications (unless prescribed by your physician) as this could slow the elimination of the contaminant.

Food Infection

According to the CDC, more than 250 different foodborne diseases have been identified.5 Most are food infections, which means they are caused from food contaminated by microorganisms (or pathogens), such as bacteria, parasites, or viruses. The infection then grows inside the body and becomes the source of symptoms. Food infections can be sporadic and often are not reported to physicians. However, occasional outbreaks occur that put communities, states and provinces, or even entire nations at risk.

Food Intoxication

Other kinds of foodborne illness are food intoxications, which are caused by natural toxins or harmful chemicals. These and other unspecified agents are major contributors to episodes of acute gastroenteritis (infection of the stomach and/or intestines) and other kinds of foodborne illness.6 Like pathogens, toxins and chemicals can be introduced to food during cultivation, harvesting, processing, or distribution. Some toxins can lead to symptoms that are also common to food infections, such as abdominal cramping, while others can cause different kinds of symptoms and complications, which can be very severe. For example, mercury, which is sometimes found in fish, can cause neurological damage in infants and children. Exposure to cadmium can cause kidney damage, typically in elderly people.

3.3 Causes of Food Contamination

Let’s begin with agents called pathogens, which include bacteria, parasites, and viruses. Approximately 100 years ago typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and cholera were common diseases caused by food and water contaminated by pathogens. Over time, improvements in food processing and water treatment has eliminated most of these problems in North America. Today, other bacteria and viruses have become common causes of food infection.

The top five pathogens that cause foodborne illness in the US include

- Norovirus,

- Salmonella,

- Clostridium perfringens,

- Campylobacter, and

- Staphylococcus aureus.

Other pathogens cause fewer illnesses, but when they do, the illnesses are more likely to require hospitalization. These include Clostridium botulinum, Listeria, E. coli, and Vibrio.5

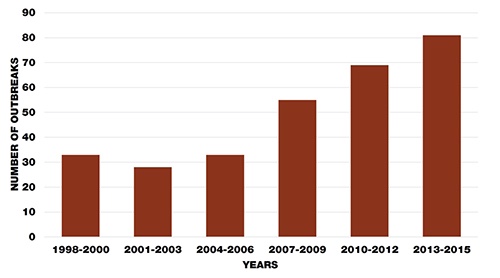

When a suspected foodborne illness outbreak occurs, the CDC is responsible for investigating and has developed a seven step process to do so. These steps are Detect, Find, Generate, Test, Solve, Control, and Decide and are explained in Figure 3.3.1. The CDC also maintains a database of past and present outbreaks.7

Bacteria: The Reproduction of Microorganisms

Bacteria, one of the most common agents of food infection, are single-celled microorganisms that are too small to be seen with the human eye. Microbes live, die, and reproduce, and like all living creatures, they depend on certain conditions to survive and thrive. In order to reproduce within food, microorganisms require the following:

- Temperature. Between 40° and 140°F is called the danger zone, where bacteria can grow rapidly.

- Time. More than two hours spent in the danger zone. Less time when the environment is warmer.

- Water. High moisture content helps bacteria grow. Fresh fruits and vegetables have the highest moisture content.

- Oxygen. Most microorganisms need oxygen to grow and multiply, but a few are anaerobic and do not require oxygen.

- Acidity and pH level. Foods that have a low level of acidity (or a high pH level) provide an ideal environment, since most microorganisms grow best around 7.0 pH and not many grow below 4.0 pH. Examples of higher pH foods include meat, seafood, milk, and corn. Examples of low pH foods include citrus fruits, sauerkraut, tomatoes, and pineapples.

- Nutrient content. Microorganisms need protein, starch, sugars, fats, and other compounds to grow. Typically, high protein foods are better for bacterial growth.

All foods naturally contain small amounts of bacteria. However, poor handling and preparation of food, along with improper cooking or storage, can multiply bacteria and cause illness. In addition, bacteria can multiply quickly when cooked food is left out at room temperature for more than a few hours. Most bacteria grow undetected because they do not change the color or texture of food or produce an odor. Freezing and refrigeration can slow or stop the growth of bacteria but do not destroy the bacteria completely. The microbes can reactivate when the food is taken out and thawed. Many different kinds of bacteria can lead to food infections.

Types of Bacteria that May Cause Foodborne Illness

One of the most common is Salmonella, which is found in the intestines of birds, reptiles, and mammals. Salmonella can spread to humans via a variety of different animal origin foods including meats, poultry, eggs, dairy products, and seafood. Symptoms include fever, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea and usually begin within 6 hours to 6 days after infection. The illness typically lasts 4 to 7 days and most people recover without treatment. However, in individuals with weakened immune systems, Salmonella can invade the bloodstream and lead to life threatening complications.8

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is found in soft cheeses, unpasteurized milk, seafood, and on produce. It causes a disease, listeriosis, that can result in symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle aches, confusion, stiff neck, and even convulsions. Listeria monocytogenes is particularly dangerous for pregnant women who often only experience fever and fatigue but can lead to devastating effects to the fetus such as miscarriage or stillbirth. Symptoms typically begin 30 days after exposure, but some have reported as late as 70 days after. Listeria is primarily treated with antibiotics.9

There are six pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli, commonly called E. coli that can cause foodborne illness. Sources include raw or undercooked meat, raw vegetables, unpasteurized milk, minimally processed ciders and juices, and contaminated drinking water. Symptoms can occur 3 to 4 days after eating, and include severe abdominal cramping, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and dehydration. Mild cases typically resolve within 5 to 7 days. More severe complications may include colitis, neurological symptoms, stroke, and hemolytic uremic syndrome.10

The bacterium Clostridium botulinum causes botulism. Sources include improperly canned foods, lunch meats, honey, and garlic. An infected person may experience symptoms within 18 to 36 hours after eating. Symptoms include nerve dysfunction, such as double vision, speech difficulty, difficulty swallowing, and progressive paralysis of the respiratory system that can lead to death. Infants less than one year old should not ingest honey because of the risk of infection with Clostridium botulinum.11 Home canned or store bought cans that are leaking, bulging, cracked or spurt liquid or foam when opened may be contaminated with this bacterium and should be thrown away.

Campylobacter jejuni is the most commonly identified bacterial cause of diarrhea worldwide. Consuming undercooked chicken or food contaminated with the juices of raw chicken is the most frequent source of this infection. Other sources include raw meat and unpasteurized milk. Within 2 to 5 days of consumption symptoms may begin and include fever, abdominal cramps, and bloody diarrhea. The duration of this disease is approximately 7 to 10 days.12

There are several types of Shigella that can cause the food infection shigellosis. Sources include undercooked liquid or moist food that has been handled by an infected person. The onset of symptoms occurs 1 to 2 days after eating, and can include fever, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea. Another common symptom is blood or mucus in the stool. Duration of infection is typically 5 to 7 days, but could take several weeks to completely resolve. Once a person has had shigellosis, the individual is not likely to get infected with that specific type again for at least several years. However, they can still become infected with other types of shigella.13

Staphylococcus aureus causes staphylococcal food poisoning. Food workers who carry this kind of bacteria and handle food without washing their hands can cause contamination. Other sources include meat and poultry, egg products, pastries, tuna, potato and macaroni salad, and foods left unrefrigerated for long periods of time. Symptoms can begin 30 minutes to 8 hours after eating and include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This food infection typically only lasts 1 to 2 days.

Found in raw oysters and other kinds of undercooked seafood, Vibrio vulnificus belongs to the same family as the bacteria which causes cholera. Symptoms typically begin within 24 hours of consumption and resolve after approximately 3 days. Symptoms include chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, and watery diarrhea. This disease can be very dangerous with approximately 1 in 5 people dying of this infection.1

Table 3.3.1 Summary of Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens

| Pathogen | Incubation Period | Symptoms | Common Culprits |

| Salmonella | 6 hours-6 days | Fever, abdominal cramping, diarrhea | Found in animal origin foods |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 30-70 days | Fever, headache, muscle aches, confusion, stiff neck, convulsions | Soft cheeses, unpasteurized dairy, produce, seafood |

| Escherichia coli | 3-4 days | Severe abdominal cramps, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, dehydration | Raw or undercooked meats, unpasteurized dairy, contaminated water, minimally processed ciders and juices |

| Clostridium botulinum | 18-36 hours | Nerve dysfunction, speech difficulty, difficulty swallowing, and progressive paralysis of the respiratory system that can lead to death | Improperly canned foods, lunch meats, honey, and garlic |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 2-5 days | Fever, abdominal cramps, bloody diarrhea | Raw or undercooked chicken |

| Shigella | 1-2 days | Fever, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea and blood, pus, or mucus in the stool | Undercooked liquid or moist food that has been handled by an infected person |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 30 minutes-8 hours | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Meat and poultry, egg products, pastries, tuna, potato and macaroni salad, and foods left unrefrigerated for long periods of time |

| Vibrio vulnificus | 24 hours | Chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea | Raw oysters, undercooked seafood |

Viruses

Viruses are another type of pathogen that can lead to food infections, however they are less predominant than bacteria. Hepatitis A is one of the more well known food contaminating viruses. Sources include raw shellfish from polluted water and food handled by an infected person. This virus can go undetected for weeks and on average, symptoms do not appear until about one month after exposure. At first, symptoms include a general feeling of discomfort (malaise), loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Three to 10 days later additional symptoms can manifest including jaundice and darkened urine. Severe cases of hepatitis A can result in liver damage and death.

The most common form of contamination from handled foods is norovirus. Sources include salads, sandwiches, and other ready-to-eat foods handled by an infected person. Norovirus causes gastroenteritis (infection in the stomach and intestines) and within 1 to 3 days it leads to symptoms such as headache, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a low grade fever.15 Norovirus is unusual in that once you are infected with norovirus through food you can pass it via person-to-person contact to someone who has not eaten the food.

Parasitic Protozoa

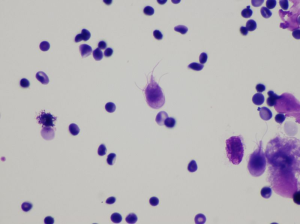

Food contaminating parasitic protozoa are microscopic single-celled organisms that may be spread in food and water. Several of these creatures pose major problems to food production worldwide. Anisakiasis occurs when microscopic anisakid worms invade the stomach or the intestines. Sources of this parasite include raw or undercooked fish and squid. Symptoms begin within a day or less and include abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, and mild fever.

Cryptosporidium is a microscopic parasite that lives in the intestines of infected animals. A common source of infection in humans is drinking water, when heavy rains wash animal waste into reservoirs, or consumption of recreational water from rivers, streams, and lakes. One major problem with this pathogen is that it is extremely resistant to disinfection with chlorine. Symptoms begin 2 to 10 days after exposure and include low grade fever, abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea, and dehydration.

Giardia lamblia is another parasite that is found in contaminated drinking water. In addition, it lives in the intestinal tracts of animals, and can wash into surface water and reservoirs, similar to Cryptosporidium. Symptoms include abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea within 1 to 3 weeks after exposure. Although most people recover in 1 to 2 weeks, the disease can lead to chronic symptoms, especially in people with compromised immune systems.

The parasite Toxoplasma gondii causes the infection toxoplasmosis, which is a leading cause of death attributed to foodborne illness in the US. More than 60 million Americans carry Toxoplasma gondii, but very few have symptoms. Typically, the body’s immune system keeps the parasite from causing disease. If symptoms are experienced, they typically are flu-like with swollen lymph glands and/or muscle aches that may last for a month or more. Sources include raw or undercooked meat, and unwashed fruits and vegetables. Handling the feces of a cat with an acute infection can also lead to disease, so people at high risk of infection, like women who are pregnant, should not scoop a cat’s litter box in order to avoid possible exposure.16

Mold Toxins

Warm, humid, or damp conditions encourage mold to grow on food. Molds are microscopic fungi that live on animals and plants. No one knows how many species of fungi exist, but estimates range from 10,000 to 300,000. Unlike single-celled bacteria, molds are multicellular, and under a microscope look like slender mushrooms. They have stalks with spores that form at the ends. The spores give molds their color and can be transported by air, water, or insects. Spores also enable mold to reproduce. Additionally, molds have root-like threads that may grow deep into food and be difficult to see. The threads are very deep when a food shows heavy mold growth.

Foods that contain mold may also have bacteria growing alongside it. Some molds, like the kind found in bleu cheese, are desirable in foods, while other molds can be dangerous. The spores of some molds can cause allergic reactions and respiratory problems. In the right conditions, a few molds produce mycotoxins, which are natural, poisonous substances that can make you sick when consumed. Mycotoxins are contained in and around mold threads, and in some cases, may have spread throughout the food. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations estimates that mycotoxins affect 25% of the world’s food crops. They are found primarily in grains and nuts, but sources include apples, celery, and other produce.

The most dangerous mycotoxins are aflatoxins, which are produced by a strain of fungi called Aspergillus under certain temperature and humidity conditions. Contamination has occurred in peanuts, tree nuts, and corn. Aflatoxins can cause aflatoxicosis in humans, livestock, and domestic animals. Symptoms include vomiting and abdominal pain. Possible complications include liver failure, liver cancer, and even death. Many countries try to limit exposure to aflatoxins by monitoring their presence on food and feed products.17

Pollutants

Pollutants are another kind of chemical contaminant that can make food harmful. Chemical runoff from factories can pollute food products and drinking water. For example, dioxins are chemical compounds created by industrial processes, such as manufacturing and bleaching pulp and paper. Fish that swim in dioxin-polluted waters can contain significant amounts of this pollutant, which can cause cancer.

When metals contaminate food, it can result in serious and even life-threatening health problems. A common metal contaminant is lead, which can be present in drinking water, soil, and air. Lead exposure most often affects children, who can suffer from physical and mental developmental delays as a result. Methylmercury occurs naturally in the environment and is also produced by human activities. Fish can absorb it, and the predatory fish that consume smaller, contaminated fish can have very high levels. This highly toxic chemical can cause mercury poisoning, which leads to developmental problems in children, as well as autoimmune effects.

Table 3.3.2 Mercury levels in fish18

| Least Mercury | Enjoy these fish often | Anchovies, catfish, clams, domestic crab, crayfish/crawfish, flounder, herring, oysters, salmon, scallops, shrimp, squid, tilapia, trout, whitefish |

| Moderate Mercury | Eat no more than 6 servings per month | Bass, carp, Alaskan cod, lobster, mahi mahi, monkfish, freshwater perch, snapper, tuna (canned chunk light or skipjack) |

| High Mercury | Eat no more than 3 servings per month | Halibut, mackerel (Spanish or Gulf), ocean perch, Chilean sea bass, tuna (albacore or yellowfin) |

| Highest Mercury | Avoid | Bluefish, grouper, king mackeral, marlin, orange roughy, shark, swordfish, tuna (big eye or ahi) |

PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, are man-made organic compounds that were used in hundreds of industries from 1929-1979. During their use they entered the air, water, and soil through wastes from manufacturing. Like methylmercury, higher concentrations of this contaminant are found in predatory fish. Health effects include physical and neurological development in children, and this compound is potentially a carcinogen. PCB contamination can also affect the immune, reproductive, nervous, and endocrine systems.19

3.4 Protecting the Public Health

Most foodborne infections go undiagnosed and unreported. However, the CDC estimates that about 76 million people in the US become ill from foodborne pathogens or other agents every year. In North America, a number of government agencies work to educate the public about food infections and intoxications, prevent the spread of disease, and quell any major problems or outbreaks.

Efforts at the Governmental Level

Protecting the public from foodborne illness is a multi-agency effort. The USDA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) enforce laws regarding the safety of domestic and imported food. In addition, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 gives the FDA authority over food ingredients. The CDC tracks outbreaks, identifies the causes of food infection and intoxication, and recommends ways to prevent foodborne illness. Other government agencies that play a role in protecting the public include the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), a division of the USDA, which enforces laws regulating meat and poultry safety. The Agricultural Research Service, which is the research arm of the USDA, investigates a number of agricultural practices including those related to animal and crop safety. The National Institute of Food and Agriculture conducts research and education programs on food safety for farmers and consumers. Also, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates public drinking water.

Government agencies also monitor the use of pesticides. The EPA approves pesticides and other chemicals used in agriculture and sets limits on how much residue can remain on food. The FDA analyzes food for surface residue and waxes. Processing methods can either reduce or concentrate pesticide residue in foods. Therefore, the Food Quality Protection Act, which passed in 1996, requires manufacturers to show that pesticide levels are safe for children.

Efforts within the Food Industry

In 1996, Congress passed the Food Safety Act which incorporated the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) system within the food industry. The FDA defines HACCP as “a management system in which food safety is addressed through the analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production, procurement and handling, to manufacturing, distribution and consumption of the finished product.”20 From growing food on farms to manufacturing it to eating food in a restaurant, HACCP is meant to provide guidance all along the food chain. This system is designed to promote food safety and prevent contamination by identifying all areas in food production and retail where contamination could occur. Companies and retailers determine the points during processing, packaging, shipping, and shelving that could be hazardous. Those companies and retailers must then take measures to prevent, control, or eliminate the potential for food contamination. The USDA requires the food industry to follow HACCP for meat and poultry, while the FDA requires it for seafood, low-acid canned foods, and juice. HACCP is voluntary for all other food products.

Table 3.4.1 Timeline of Governmental Intervention for Prevention of Food Contamination21

| 1862 | Abraham Lincoln founds the USDA |

| 1890 | Cattle and beef intended for export require inspection and certification |

| 1906 | Upton Sinclair publishes “The Jungle” unintentionally prompting Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and Federal Meat Inspection Act; Voluntary egg inspection added in 1912 |

| 1927-1931 | FDA created |

| 1938 | Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act passes giving the FDA authority to issue food safety standards |

| 1946 | USDA begins inspecting and grading quality of meat products |

| 1957 | Poultry Products Inspection Act passes |

| 1967 |

Fair Packaging and Label Act enacted to prevent unfair/deceptive packaging and labeling on many products including Food; Name and location of manufacturer, packer, and/or distributor and net quantity of contents is now required |

| 1970 | CDC begins keeping records on foodborne illnesses; Egg inspection becomes mandatory |

| 1973 |

First major food recall in the US; More than 75 million cans of mushrooms removed from store shelves |

| 1981 | Division of meat/poultry/egg inspection renamed Food Safety and Inspection Service |

| 1993 | E. coli outbreak in ground beef causes 400 illnesses and 4 deaths—public demands change for safer ground beef products |

| 1996 |

Food Quality Protection Act passed; Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) incorporated into 1996 Food Safety Law |

| 2009 |

Country of Origin Labeling for meat, poultry, wild/farm raised fish/shellfish, fresh/frozen fruits and vegetables, and some nuts is required |

| 2010 |

Food Safety Modernization Act expanding the scope of FDA authority and inclusion of mandatory preventive controls and safety standards |

| 2020 |

Blueprint for a New Era of Smarter Food Safety is announced focusing on enhanced traceability, improved predictive analysis, more rapid responses to outbreaks, and business and retail model modernization |

The Food System

The food system is a network of farmers and related operations including food processing, wholesale and distribution, retail, industry technology, and marketing. The milk industry, for example, includes everything from the farm that raises livestock, to the milking facility that extracts the product, to the processing company that pasteurizes milk and packages it into cartons, to the shipping company that delivers the product to the stores, to the markets and grocers that stock and sell the product, to the advertising agency that touts the product to the consumers. All of these components play a part in a very large system.

Two important aspects of a food system are preservation and processing. Each provides for or protects consumers in different ways. Food preservation includes the handling or treating of food to prevent or slow down spoilage. Food processing involves transforming raw ingredients into packaged food, from fresh-baked goods to frozen dinners. Although there are numerous benefits to both, preservation and processing also pose some concerns, in terms of both nutrition and sustainability.

Food Preservation

Food preservation protects consumers from harmful or toxic food. There are different ways to preserve food. Some are ancient methods that have been practiced for generations such as curing, smoking, pickling, salting, fermenting, canning, and preserving fruit in the form of jam. Others include the use of modern techniques and technology including drying, vacuum packaging, pasteurization, freezing and refrigeration. Preservation guards again foodborne illnesses and also protects the flavor, color, moisture content, and/or nutritive value of food.

Food Irradiation

Food irradiation (the application of ionizing radiation to food) is a technology that improves the safety and extends the shelf life of foods by reducing or eliminating microorganisms and insects. Like pasteurizing milk and canning fruits and vegetables, irradiation can make food safer for the consumer. Irradiation does not make food radioactive, compromise nutritional quality, or noticeably change the taste, texture, or appearance of food.

Irradiation can serve many purposes:

- Prevention of foodborne illness. To effectively eliminate organisms that cause foodborne illness, such as Salmonella and E. coli.

- Preservation. To destroy or inactivate organisms that cause spoilage and decomposition thereby extending the shelf life of foods.

- Control of insects. To destroy insects in or on tropical fruits imported into the US. Irradiation also decreases the need for other pest control practices that may harm fruit.

- Delay sprouting and ripening. To inhibit sprouting (e.g., potatoes) and delay ripening of fruit to increase longevity.

- Sterilization. To sterilize foods, which can then be stored for years without refrigeration.

The FDA has evaluated the safety of irradiated food for more than 30 years and has found the process to be safe. The World Health Organization (WHO), the CDC, and USDA have also endorsed the safety of irradiated foods. The FDA has approved a variety of foods for irradiation in the US including:

- Beef and pork

- Crustaceans (e.g., lobsters, shrimp, and crab)

- Fresh fruits and vegetables

- Lettuce and spinach

- Poultry

- Seeds for sprouting (e.g., for alfalfa sprouts)

- Eggs

- Shellfish (e.g., oysters, clams, and mussels)

- Spices and seasoning

It is important to remember that irradiation is not a replacement for proper food handling practices by producers, processors, and consumers. Irradiated foods need to be stored, handled, and cooked in the same way as non-irradiated foods because they could still become contaminated with disease causing organisms after irradiation if the rules of basic food safety are not followed. The FDA requires that irradiated foods exhibit the international symbol of irradiation, the Radura. It also requires the food label to contain a statement like “Treated by irradiation” or “Treated with radiation.”22

Pasteurization

Pasteurization is named for French microbiologist Louis Pasteur. It is a process of heating a food or beverage to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life. Routine pasteurization in the US began in the 1920s and has been widespread since the 1950s. Pasteurization is considered one of the most effective food safety interventions ever.

Raw or unpasteurized milk, including other products made with it such as soft cheese (queso fresco, feta, etc.), can carry harmful organisms including Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, E. coli, Listeria, and Salmonella. These organisms typically do not change the look, taste, or smell of milk, so only when milk has been pasteurized can you be certain that these germs were killed. Additionally, pasteurization does not affect the nutritional quality of the product.23

Food Additives

If you examine the label for a processed food product, it is not unusual to see a long list of added materials. These natural or synthetic substances are food additives and there are more than 300 used during food processing today.

Food additives are introduced in food processing for a variety of reasons. Some control acidity and alkalinity, while others enhance the color or flavor of food. Some additives stabilize foods and keep it from breaking down, extending shelf life, while others add body or texture.

Table 3.4.2 Select Food Additives

| Additive | Reason for Adding |

| Beta carotene | Adds artificial coloring to food |

| Caffeine | Acts as a stimulant |

| Citric acid | Increases tartness to prevent food from becoming rancid |

| Dextrin | Thickens gravies, sauces, and baking mixes |

| Gelatin | Stabilizes, thickens, or adds texture to food |

| Modified food starch | Keeps ingredients from separating and preventing lumps |

| Monosodium glutamate (MSG) | Enhances flavor in a variety of foods |

| Pectin | Gives candies and jams a gel-like texture |

| Polysorbates | Blends oil and water and keep them from separating |

| Soy lecithin | Emulsifies and stabilizes chocolate, margarine, and other items |

| Sulfites | Prevents discoloration in dried fruits |

| Xanthan gum | Thickens, emulsifies, and stabilizes dairy products and dressings |

Pros and Cons of Food Additives

The FDA works to protect the public from potentially dangerous food additives. Passed in 1958, the Food Additives Amendment states that a manufacturer is responsible for demonstrating the safety of an additive before it can be approved. The Delaney Clause was added to this legislation prohibiting the approval of any additive found to cause cancer in animals or humans. Most additives are considered to be “generally recognized as safe,” a status that is determined by the FDA and referred to as GRAS.

Food additives are typically included in the processing stage to improve the quality and consistency of a product. Many additives also make items more “shelf stable,” meaning they will last a lot longer on store shelves and can generate more profit. Additives can also help prevent spoilage that results from changes in temperature, damage during distribution, and other adverse conditions. In addition, food additives can protect consumers from exposure to rancid products and some foodborne illness.

Food additives are not always beneficial, however. Some substances have been associated with certain diseases if consumed in large amounts. For example, the FDA estimates that sulfites can cause allergic reactions in 1% of the general population and 5% of those with asthma. Similarly, the additive monosodium glutamate, more commonly known as MSG, may cause headaches and rapid heartbeat in some individuals.

Manufacturers must list food additives on ingredient lists on food packaging. Food coloring must be listed individually (such as Blue No. 1 or Red No. 5), but other food additives can be listed collectively as “artificial flavoring” or “spices.” The FDA has specific rules for food additives regarding labeling requirements.24

3.5 Efforts at the Consumer Level: What You Can Do

Consumers can also take steps to prevent foodborne illness and protect their health. Although you can often see when mold is present, you cannot see, smell, or taste bacteria or other agents of foodborne infection or intoxication. Therefore, it is crucial to take measures to protect yourself. The four most important steps for handling, preparing, and serving food are25:

- Clean. Wash hands thoroughly. Clean surfaces often and wash utensils after each use. Wash fruits and vegetables (even if you plan to peel them).

- Separate. Do not cross-contaminate food during preparation or storage. Use separate cutting boards, plates, and utensils for raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs. Do not use the same utensils or plates for both raw and cooked foods without cleaning thoroughly between. Store food products separately in the refrigerator.

- Cook. Food is safely cooked when the internal temperature gets high enough to kill pathogens. The only way to determine this is by using a food thermometer to check the temperature of food while it is cooking. Keep food hot after it has been cooked.

- Chill. Refrigerate any leftovers within two hours. Thaw frozen food in the refrigerator, cold water, or the microwave. Do not thaw foods on the counter.

Storing Food

Check storage directions on packaged food items and follow them. Many food items need to be kept cold. Refrigerate perishable foods quickly; they should not be left out for more than two hours. If the outdoor temperature is above 90°F, refrigerate within one hour. The refrigerator should be kept at 40°F or colder. Store eggs in a carton on a shelf in the refrigerator and not in the refrigerator door where the temperature is warmest. Wrap meat packages tightly and store them at the bottom of the refrigerator, so juices won’t leak out onto other foods. Raw meat, poultry, and seafood should be kept in a refrigerator for only two days. Otherwise, they should be stored in the freezer, which should be kept at 0°F or colder. Items in the freezer should remain safe indefinitely without loss of nutrients. However, if frozen for long periods, quality may suffer.26 Store potatoes and onions in a cool, dark place, but not under a sink as a leak could contaminate them. Empty opened cans of perishable foods or beverages into containers, and promptly place them in a refrigerator. Also, be sure to consume leftovers within three to five days, so that mold does not have a chance to grow. If something does look moldy, throw it out. As we discussed in Chapter 2, manufacturers are allowed to put dates on packaging. With the exception of infant formula and some baby food, all dates refer to the quality of the food. They are not about the safety of the food.

Table 3.5.1 Date Labeling Explanations

| Term | Explanation |

| Best if Used By/Before | Indicates when a product will be of best flavor or quality; it is not a safety date |

| Sell by | Tells the store how long to display the product for sale or inventory management; typically refers to quality (freshness, taste, consistency) and is not a safety date |

| Use by | Last date recommended for the use of the product at peak quality; determined by the manufacturer; is not a safety date except for when used on infant formula |

| Guaranteed Fresh | Typically used on bakery items; identifies when food will be at peak freshness; is not a safety date |

Preparing Food

Wash hands thoroughly with warm, soapy water for at least 20 seconds before preparing food and every time after handling raw foods. Washing hands is important for many reasons. One is to prevent cross-contamination between foods. Also, some pathogens can be passed from person to person, so hand washing can help to prevent this. Fresh fruits and vegetables should be rinsed thoroughly under running water to clean off residue such as dirt and bacteria. You should not wash raw poultry or meat before cooking it, even though some older recipes may call for this step. Washing raw poultry or meat can spread bacteria to other foods, utensils, and surfaces, and does not prevent illness.27

Other tips to keep foods safe during preparation include defrosting meat, poultry, and seafood in the refrigerator, microwave, or in a water-tight plastic bag submerged in cold water. Never defrost at room temperature as that is an ideal temperature for bacteria to grow. Also, marinate foods in the refrigerator and discard leftover marinade after use because it contains raw juices.25 Always use cutting boards that have been cleaned with soap and warm water by hand or in a dishwasher after each use. Cutting boards can also be sanitized by rinsing them with a solution of 5 ml (1 tsp) chlorine bleach to 1 liter (1 quart) of water. Check canned foods for leakage, punctures, or denting severe enough that you couldn’t stack the can or open it with a manual can opener. Also, wipe the top of cans to ensure that no contaminants get introduced when opening.

Cooking Food

Cooked food is safe to eat only after it has been heated to a temperature that is high enough to kill bacteria. You cannot judge the state of “cooked” by color or texture alone. A food thermometer must be used to be sure. The appropriate minimum cooking temperature varies depends upon the type of food25:

- 145°F for whole cuts of beef, pork, veal, and lamb (allowing the meat to rest for 3 minutes before carving or eating)

- 160°F for ground meats, such as beef and pork

- 165°F for all poultry including ground chicken and turkey

- 165°F for leftovers and casseroles

- 145°F for fresh ham (raw)

- 145°F for fish

Serving Food

After food has been cooked, the possibility of bacterial growth increases as the temperature drops. Food should be kept above the safe temperature of 140°F using a heat source such as a chafing dish, warming tray, or slow cooker. Cold foods should be kept at 40°F or lower. When serving food, keep it covered to block exposure to any mold spores in the air. Use plastic wrap to cover foods that you want to remain moist, such as fresh fruits, vegetables, and salads. Do not keep food at room temperature for more than two hours. They should be refrigerated as promptly as possible. It also helps to date leftovers, so they can be used within a safe time frame, which is generally 3 to 5 days when stored in a refrigerator.

Food for Thought

Discuss tactics that government agencies or consumer groups could take to educate the public about food safety. What key points do you think consumers need to know about food safety? What key points do you think consumers need to know about foodborne illness and food safety? How do you think government organizations or other groups can best get that information out to the public?

3.6 Preparing for Disasters

In the event of a disaster, it is important to make sure you and your family have enough safe food and water (for drinking, cooking, bathing, etc.) available.

Emergency Food Supply

It is recommended to have at least a three day supply of food on hand. It is not necessary to buy dehydrated or specialty foods. Canned foods and dry mixes will remain fresh for approximately two years. Date all food items, so that they can be used and replaced before they lose their freshness. Certain storage conditions can enhance the shelf life of canned or dried foods. The ideal location is a cool, dry, dark place with temperatures between 40 to 60°F. Higher temperatures may cause many foods to spoil more quickly.

Keep foods that:

- have a long shelf life

- require little or no cooking, water, or refrigeration, in case utilities are disrupted

- meet the needs of babies or other family members who are on special diets

- meet pets’ needs

- are not very salty or spicy, as these foods increase the need for drinking water, which may be in short supply

It is recommended to keep food away from petroleum products, such as gasoline, oil, paints, and solvents to prevent possible contamination. Additionally, some food products absorb these odors. It is also important to protect food from rodents and insects. Items stored in boxes or in paper cartons will keep longer if they are heavily wrapped or stored in airtight containers.

Emergency Water Supply

It is recommended to have at least one gallon of drinking water per day for each person and pet. More may be necessary in hot climates, for pregnant/lactating women, and for persons who are ill. A three day to two week supply is recommended. Store bought water often has an expiration date. Consider replacing stored water every six months. Please note that caffeinated drinks and alcohol dehydrate the body, which increases the need for drinking water.

Preparing Food

Preparing food after a disaster or emergency may be difficult due to possible damage to your home and loss of electricity, gas, and water. Having the following items available will help you to prepare meals safely:

- Cooking utensils

- Knives, forks, and spoons

- Paper plates, cups, and towels

- A manual can- and bottle-opener

- Heavy duty aluminum foil

- Gas or charcoal grill; camp stove

- Fuel for cooking, such as charcoal (*Never burn charcoal indoors. The fumes are deadly when concentrated indoors)

Key Takeaways

- Foodborne illness is caused by pathogens (such as bacteria and viruses), toxins (such as those produced by molds), and chemical contaminants (such as pesticide residues and pollutants).

- Food infections are caused by food contaminated with microorganisms such as bacteria or viruses, while food intoxications are caused by natural toxins or harmful chemicals.

- Some groups are at higher risk of severe illness after exposure to a foodborne pathogen including infants and young children, women who are pregnant or lactating, older adults, and those with compromised immune systems.

- A number of government agencies work to regulate food, manage outbreaks, and inform the public about foodborne illness and food safety.

- There are many ways food producers and manufacturers attempt to minimize food contamination including irradiation, pasteurization, and refrigeration.

- Many foods contain natural or synthetic additives which affect foods in several ways to help improve the quality and consistency of a food product. However, they may not all be beneficial and may cause negative side effects in some people.

- Consumers also should take measures to protect their health including following the rules for four key steps: clean, separate, cook and chill.

- When preparing for a disaster it is important to have a supply of food, water, and cooking items available, stored in a cool, dry place.

Portions of this chapter were taken from OER Sources listed below:

Tharalson, J. (2019). Nutri300:Nutrition. https://med.libretexts.org/Courses/Sacremento_City_College/SSC%3A_Nutri_300_(Tharalson)

Titchenal, A., Calabrese, A., Gibby, C., Revilla, M.K.F., & Meinke, W. (2018). Human Nutrition. University of Hawai’i at Manoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program Open Textbook. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu

Zimmerman, M., & Snow, B. (2012). An Introduction to Nutrition, v. 1.0. https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/an-introduction-to-nutrition/

Additional References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, November 5). Estimate of foodborne illness in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, December 1). Making Food Safer to Eat. CDC Vital Signs. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/FoodSafety

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, November 15). CDC and food safety. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/cdc-and-food-safety.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, January 24). People with a higher risk of food poisoning. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/people-at-risk-food-poisoning.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 18). Foodborne germs and illness. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html

- Scallan, E., Griffin, P. M., Angulo, F. J., Tauxe, R. V., & Hoekstra, R. M. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—Unspecified agents. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 16-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1701.p21101

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 22). Foodborne Outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 20). Salmonella. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 10). Listeria. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, February 26). E. coli. https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 19). Botulism. https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 23). Campylobacter. https://www.cdc.gov/campylobacter/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, November 13). Shigella. https://www.cdc.gov/shigella/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, March 5). Vibrio species causing vibriosis. https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 5). Norovirus. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, June 26). Toxoplasmosis and pregnancy FAQs. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/gen_info/pregnant.html

- United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service. (2013, August 22). Molds on food: Are they dangerous? https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/get-answers/food-safety-fact-sheets/safe-food-handling/molds-on-food-are-they-dangerous_/ct_index

- Greenfield, N. (2015, August 26). The smart seafood buying guide. National Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/smart-seafood-buying-guide

- US Environmental Protection Agency. (2020, February 6). Health effects of PCBs.https://www.epa.gov/pcbs/learn-about-polychlorinated-biphenyls-pcbs#healtheffects

- Food and Drug Administration. (2018, January 29). Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points. https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-regulation-food-and-dietary-supplements/hazard-analysis-critical-control-point-haccp

- United States Department of Agriculture Food Inspection and Safety Service. (2018, February 21). FSIS history. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/informational/aboutfsis/history

- Food and Drug Administration.(2018, January 4). Food irradiation: What you need to know. https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/food-irradiation-what-you-need-know#

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, June 8). Raw milk. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/rawmilk/raw-milk-index.html

- Food and Drug Administration.(2018, February 6). Overview of Food Ingredients, Additives & Colors. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/overview-food-ingredients-additives-colors

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 18). Four steps to food safety. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/keep-food-safe.html

- Food and Drug Administration. (2018, April 6). Are you Storing Food Safely? https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/are-you-storing-food-safely

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, October 11). Foods that can cause food poisoning. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foods-linked-illness.html

Media Attributions

- USDA: Food Recalls by Category

- Salmonella

- Escherichia coli

- Dented Can of Pear Halves

- Campylobacter

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Giardia lambda

- Aspergillus flavus on corn

- Radura Symbol for Irradiated Food

- Four Steps to Food Safety

a microorganism that can cause disease

poisonous substance produced within living cells or organisms

Infection caused when ingested food contains a pathogen (bacteria, virus, etc)

Occurs when ingested food contains a toxin such as mold or toxic pollutants

time between exposure to a pathogen or toxin and the onset of physical symptoms

Bacterial or viral agents that cause illness.

Natural, poisonous substances contained in molds that develop in crops such as grains, nuts, and produce.

Chemical compounds created during manufacturing that can pollute water sources. Fish become contaminated, and the compounds can cause cancer.

The handling or treatment of food to prevent or slow spoilage. Preservation techniques include refrigeration, curing, smoking, canning, picking, drying, vacuum packing, and pasteurization.

The transformation of raw ingredients into packaged foods

The application of ionizing radiation to food that improves the safety and extends the shelf life of foods by reducing or eliminating microorganisms and insects.

Is a process of heating a food or beverage to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life.