1

Corequisites are a way for students who are not quite college-ready to take a college-level course while also taking a developmental course that provides additional support and guidance. The two paired sections will share 12-16 students who have not scored “college reading” in the reading and/or writing sections of the TSI placement test.

The college credit course is often the first class students are expected to take in their major pathway. The other section is an INRW (Integrated College Reading and Writing) course that will provide students with instruction and support focused on the reading, writing, and studying requirements of the paired college credit course as well as college courses in general.

Background

A handful of states (including California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Tennessee) have begun to fundamentally re-think developmental education and are engaged in pilots and initiatives to figure out models that might better support underserved student populations—for example, veterans, first-generation students, students of color and students who may have physical and/or learning disabilities.

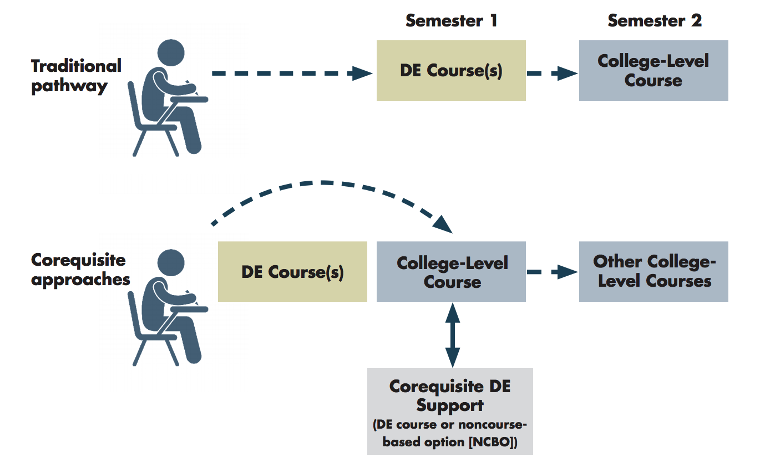

“Corequisites” entered as a model (made prominent by the Community College of Baltimore County’s Accelerated Learning Program model and as studied by the Community College Research Center) where entering college students, rather than enrolling in consecutive semesters of developmental coursework then credit-bearing coursework, co-enroll in transfer-level English, math or other gateway courses alongside a form of developmental education support:

College Readiness

All iterations of developmental education exist to address the reality that many students entering higher education institutions today are not able to establish “college readiness” in reading, writing and/or math. As an aside, the term “college-ready” is a malleable one and students have many potential avenues for proving this (only recently have the TEA and THECB moved to better align their definitions and standards, for example).

So how many students fall into this “not college ready” category? The American Institutes of Research’s Factsheet from 2018 gives us an idea:

- 20% of incoming freshmen at 4-year institutions and 52% of those at 2-year colleges (nationally) will need some type of developmental coursework in reading, writing and/or math.

- In Texas, 42.6% of total first-time higher education students are “not college-ready.” In 2-year colleges, it’s 61%.

So, to sum up, corequisites emerge in an environment where there has been:

- A crisis in “college readiness”

- A national push toward acceleration

- Legislation mandating alternatives to traditional Developmental Education

- A statewide reorganization of developmental education.

Developmental Education Reforms in Texas (2011-2018)

If we look at the history of developmental education reforms in the past decade in Texas, we can see a number of attempts that have been made to address the needs of this student population:

- 2009: Non-Course Based Options (NCBOS)

- Provided funding for outside-the-classroom DE support in reading, writing, math (often through mandatory writing center tutoring or competency-based computer modules).

- 2011: Corequisites (aka Mainstreaming)

- SB 162 charged the THECB with creating a statewide DE plan including approaches to acceleration (which included corequisite models).

- 2012-2013: Common Standards for College Readiness

- HB 1244 granted the THECB the authority to establish a single set of standards for college readiness which eventually became the TSIA (Texas Success Instrument Assessment). Cut scores were established for all colleges.

- 2015: Holistic Advising (multiple measures)

- Tests are useful but must be used in combination with other measures to ensure the accuracy of class placement.

- 2015: Integration of Reading and Writing

- All Texas public institutions were required to integrate exit-level reading and writing DE offerings into a single course by Spring 2015.

- 2017: Acceleration and Reform

- HB2223 reduced the maximum number of funded DE contact hours from 27 to 18 hours per student in community college; Texas also has performance-based funding that incentivizes completion of DE.

Corequisites in Texas

House Bill 2223 mandated corequisites for higher education institutions in Texas. They defined CoReq/Mainstreaming as:

“an instructional strategy whereby undergraduate students are…co-enrolled or concurrently enrolled in a developmental education course or NCBO…and the entry-level freshman course of the same subject matter in the same semester.”

Furthermore, HB223 requires a certain percentage of students at each college to be enrolled in “CoReq” models:

- 25% by 2018-19

- 50% by 2019-2020

- 75% by 2020-2021

Additionally, there has been speculation that a 100% mandate will be required for the 2021-2022 academic year though this has not been officially announced. These percentages apply to “any underprepared student” who does not qualify for a “waiver” (for example, those testing into Adult Basic Education or any who would normally qualify for a TSI exemption waiver).

According to a 2018 Rand Study specifically looking at corequisites in Texas, there are five common models currently implemented in the state:

- Paired Courses: DE support that looks relatively like a DE course; students are enrolled simultaneously.

- Extended Time: DE support is largely an extension of the college-level class, often taught by the same instructor with additional instruction time.

- ALP (Accelerated Learning Program): DE support is provided in the classroom to a small group of students while the college-level Pairs course has a mix of DE students and college-ready students (10/10 is recommended); all colleges doing this currently use the same instructor across both classes.

- Academic Support Service: DE support is offered through mandatory academic support services such as writing-center attendance or office hours.

- Technology-Mediated Support: DE support is offered through computer-adaptive modules in lab settings and may be competency-based.

Challenges and Criticisms

This latest iteration of developmental education (by the way, if you are looking for a general overview of the history of the discipline, see this primer) is meant to do what all forms of the discipline are: help students succeed in college. So, how do corequisites compare to other reforms or models? Many organizations, most prominently Complete College America, look at promising data and assert that, yes, this is a model that should be replicated to scale. Indeed, in 2014, 22 states and the District of Columbia committed to ensuring that developmental students complete a gateway course within one year through corequisite models.

There are, however, many who point out that the success of corequisites should be not be accepted at face value; they argue that the data is based upon apples-to-oranges comparisons (different intervention models, different course subjects, different instructor approaches, different definitions of “success”) and so is not as conclusive as it seems. Furthermore, they worry that this is a model that—rather than closing achievement gaps—leaves many students without the reading, writing and quantitative skills needed to truly succeed in their college-level coursework.

So, the essential question remains: are corequisites creating access and opportunity for all students? Or creating a sink-or-swim scenario for students who may need more time? There are no easy answers but this is the debate at hand.

Paired-Course Models

But, in a sense, corequisites aren’t really a new initiative. There have been many similar models under the umbrella of “developmental education” for many years. In fact, perhaps the most productive comparison would be that of faculty learning communities. So are “corequisites”—in the most common paired-course model—just learning communities by another name?

There are some key differences for teams working in this model:

- They are mandated by the state

- Partners are often pre-determined

- Often represent a reduction in overall credits/instructional time

- “Polygamous partnerships” are common 🙂

However, the “best practices” for learning communities may be a helpful starting point for this work. We lay out the expectations of teams working together in the chapter on “Team Teaching.“