6

Allegra Villarreal

Rationale: Writing is a complex process that requires a student-centric model to guide learners who are under-prepared in written literacy skills. By introducing students to the concept of “the writing process,” and modeling prewriting, writing and rewriting strategies, we can help students improve their writing in our courses.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=YzO7OlxlidI

For the text version of the above video, see below:

Introduction

What makes writing….good? We all know good writing when we see it or claim to; we may even be able to point out a pithy phrase, striking metaphor, a solid premise if asked. But, taken on the whole, what exactly makes a composition successful? What pushes writing from basic communication into transcendent expression? What are the mechanisms at work and how can we teach them? Can we teach them at all?

Writing instructors and composition scholars alike have mulled over these questions for decades. Waves of theory crested into teaching approaches that have defined the “writing classroom” for millions of first-year composition students. Everything from workshopping multiple drafts to the preference of argumentation over other forms of discourse–many of the assumptions about what we should be teaching in English class are rooted in often contradictory theories about what good writing is at the college level.

Process Theory

“Process Theory of Composition” is a field of composition studies that focuses on writing as a process rather than a product. In 1972, Donald M. Murray’s influential pamphlet “Teach Writing as a Process not a Product” proved a foundational text of the movement, and much of today’s English instructional practice is rooted in its basic principles. In his short essay, Murray argues that the English teacher, who often has a background in literary criticism, holds student writing up to the standards of published literature and that this has negative consequences for both teacher and student:

Our students knew it wasn’t literature when they passed it in, and our attack usually does little more than confirm their lack of self-respect for their work and for themselves; we are as frustrated as our students, for conscientious, doggedly responsible, repetitive autopsying doesn’t give birth to live writing.

Murray advises instructors to instead focus their energies on helping students discover their own voices, examine their own assumptions, and be guided through a process of “discovery through language” that involves stages of prewriting, writing, and rewriting.

Various theories emerged subsequently, referring to the same process vs. product dichotomy. For example, James McCrimmon called it “writing as a way of knowing” vs. “writing as a way of telling” while Linda Flower termed it “writer-based” vs. “reader-based” prose. No matter the terms, this distinction between the two was set, and by the early 1980s, process-oriented pedagogy was the dominant instructional approach employed in writing classrooms–from elementary school to university– throughout the United States.

Stages of Writing

Murray indicates that there are three stages of writing, but that the time spent in each varies based on the writer’s personality, work habits, and the challenge of the writing task itself.

-

- Prewriting is, in Murray’s words, “everything that takes place before the first draft” and he argues that this is where 85% of writing happens. This includes daydreaming, researching, taking in opinions, forming arguments, developing audience awareness, and imagining the form of the writing to come.

- Writing is drafting. Putting the musings of the mind to paper in their first draft. This is often the fastest and scariest part of the process as it makes clear everything the writer knows, and everything the writer does not yet fully understand.

- Rewriting involves looking back at one’s subject, audience, and form with a clearer purpose and greater precision. What do I need to explain better? What is the best way to present this information? To prove my points? To move my audience to action or greater understanding? These are the considerations the author must make and then redesign, reimagine, research, and rewrite accordingly.

-

-

- Editing is also part of this final stage; it involves considering one’s piece line-by-line and even word-by-word. A rewrite will often take much longer than the first draft of an essay, article, book, or story.

-

Implications and Teaching Strategies

Murray also outlines 10 Implications to this approach at the end of his essay, and they give an indication as to how instructors can teach composition as a “process” rather than a “product” in their classrooms:

-

- Student texts are important artifacts in a writing classroom; they should be examined and studied with an analytical eye toward the writer’s choices. Consider utilizing techniques such as peer review, and group workshopping of drafts, as well as analyzing previous student samples to highlight student-authored texts in the classroom.

- Students should find their own subjects/topics within broadly defined parameters. Consider creating some assignments that allow for student choice in terms of topics and direction; the ability to follow their own interests and instincts will give confidence and generate innate curiosity.

- Students should be allowed to use their own language/expressions in their writing. Consider whether corrections or suggestions made to student writing may be inhibiting authentic expression.

- Students should draft as much as they need. Each new draft is “equal to a new paper.” Consider instituting a period of time in your course plan that allows for ungraded drafting and the opportunity to workshop and get feedback while in process.

- Students should be encouraged to find any form of writing which helps communicate what they have to say–since the focus is on the process, “creative” and “functional” writing go through the same process. Consider the types of writing forms and tasks you assign and ensure that students have the opportunity to respond both formally and informally as well as across genres and modes.

- Mechanics should be addressed last and focus on those areas which would obscure meaning for the reader. Consider centering grammatical and mechanical correction on the errors that obscure or alter the writer’s meaning and explain the errors in these terms.

- Deadlines are essential to creating “time pressure” though enough space should be created in a course for each stage. Consider allowing time in the course schedule for “prewriting” activities and research prior to embarking on the writing task itself.

- Feedback should be framed as an opportunity to indicate what other choices a writer may have made. Consider grading only the final drafts of projects while providing feedback on ungraded drafts that come before.

- Students can self-pace up until the deadline–exploring their own process. Consider allowing students to submit drafts of any length or form for ungraded feedback.

- In writing, instructors should emphasize the lack of absolutes. What works for one form, audience, or purpose may not work for another. It is important that students understand this.

Criticisms and Alternatives

On reading Murray’s piece, it seems clear that his aim was to unleash creativity in students and to allow them more agency in the writing classroom. While this approach was revolutionary for its time, by the 1990s, some scholars began criticizing the “writing-as-a-process” model as it was being taught in classrooms. These criticisms broadly fell into three buckets; firstly, it was argued that the three-part structure had incorrectly codified these “stages” as linear rather than recursive:

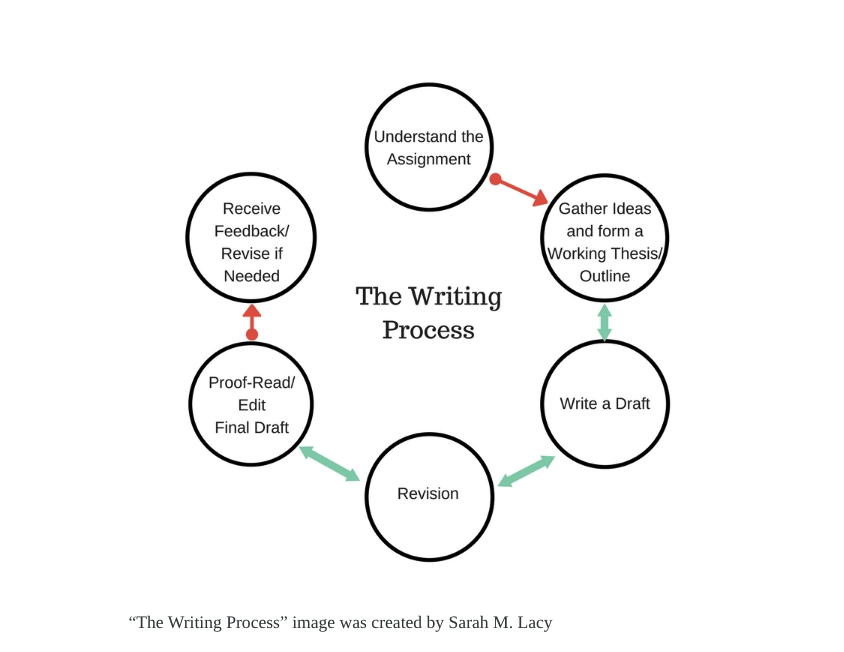

In reality, while stages may exist in writing practice, they often overlap and converge; in the revision stage, a writer may need to brainstorm again. In the editing stage, a writer may find a crucial piece of research missing and need to backtrack. Modern interpretations and iterations of the writing-as-a-process model usually acknowledge this graphically through cyclical representations:

The second criticism is a more crucial one because it goes back to the question of what good writing is and whether this model reinforces the norms of dominant discourse. For example, if an instructor requires students to complete an outline before progressing to a draft, they may be stifling other valid and organic ways of approaching a writing task. The belief that this process is the process, could leave new writers, multilingual writers, and those with less experience in academia at a disadvantage when they fail to follow these steps of “good writing” as they are laid out. While it seems clear that this was not Murray’s original intent, these are the reasons for the alternative approach known as “post-process.”

Post-Process theorists offer the third criticism. They argue that writing–and communication more broadly–cannot be distilled into a discrete model, or “closed system,” of mental processes because the minds of readers and writers are rarely standardized in this way. By extension, they also assert that it is impossible to teach writing as a thing at all because writing is “public…interpretive…and situated” as Thomas Kent writes in the introduction to Post-Process Theory, published in 1999. While students may be able to learn “hacks” for specific assignments, the topic, occasion, reader and writer mindsets are always in flux so writing is not something to be mastered but rather exercised. In terms of writing instruction, this is essentially a reversal of the skill-based, or model-based approach in favor of a more collaborative and individualized curriculum.

Today, writing instructors often find themselves teaching all of the above. A recursive approach to the writing process, for example, alongside assignments that are collaborative in terms of content and assessment to account for multiple literacies, voices, and values.

Guiding Principles for Writing-as-a-Process

For CoRequisite courses, faculty are expected to:

-

- Guide students through the writing process, embedding both low and high stakes assignments in the curriculum

- Introduce and model prewriting/idea generation strategies (see below)

- Introduce and model drafting strategies including outlining, sentence and paragraph construction, and thesis/topic sentence cohesion

- Guide students through the process of revising and editing their own work

- Provide instructor feedback, as well as the opportunity for peer review, and self-reflection on major assignments

- Grade the final drafts of essays after a writing process (including drafting and revising) has been completed

Classroom Activities