367

Table of Contents

- How to Read a Short Story

- Elements of Fiction

- Romantic

- Realist

- Modernist

- Post Colonial

- Contemporary

How to Read a Short Story

1. As in poetry, it’s important to read the story first simply to enjoy it. Read carefully and try to understand what is happening in the story.

2. Next, read the story with a pen in hand, annotating as you read. Underline lines you find important, take notes. Circle words you don’t know and look up definitions. In this step, you are trying to uncover more meaning. Look at how the elements of fiction help the author to convey the theme/meaning of the story.

“How to Read a Short Story” created by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed under CC BY NC SA.

Elements of Fiction

Theme:

The theme of a story is what the story tells the audience about what it means to be human. This is often done through the journey of the main character–what they learn is perhaps what the audience is meant to learn, as well. Theme might incorporate broad ideas, such as life/death, madness/sanity, love/hate, society/individual, known/unknown, but it can also be focused more on the individual–ie midlife crisis or growing up.

This video focuses on theme from a film perspective, but it is an interesting discussion that is also applicable to the short story.

Characters/Archetypes

The characters are the people in a story. The narrator is the voice telling the story–the narrator may or may not be a character in the story. The protagonist is the central character. The antagonist is the force or character that opposes the main character.

The way an author creates a character is called characterization. Characters might be static (remain the same) or dynamic (change through the course of the story). Authors might make judgments, either explicit (stated plainly) or implicit (allowing the reader to judge), about the characters in a story.

When reading fiction, look for common archetypes. For example, some common female archetypes are the mad woman in the attic, the spinster, the good wife, and the seductress. For a great recap of common female archetypes, read this article.

Here’s a video on Archetype and Characterization from Shmoop:

Plot

The plot is the action of the story. It’s what is happening. An author might include foreshadowing of future events. There will be a conflict, a crisis (the turning point), and a resolution (how the conflict is resolved).

Another great video from Shmoop to describe plot:

Structure

The structure is the design or form of the story. The structure can provide clues to character and action and can mirror the author’s intentions. Look for repeated elements in action, gestures, dialogue, description, and shifts.

Here’s one way to look at this:

Setting

Setting is simply where and when the story takes place. Think of the typical fairy tale…”long ago, in a land far away…”

One more video from Shmoop on Setting:

Point of View

A text can be written from first (I/me), second (you), or third person (he/she/it) point of view.

Video on Point of View–a little long, but some really interesting things to think about!

Language & Style

Language and style are how the author presents the story to the reader. Look for diction, symbols, and irony.

- Diction: Diction is the way the author chooses to use words in the story. For example, authors might use formal or informal (everyday) language, slang, or colloquial diction in their work. The diction an author chooses helps to create the tone of the work. For example, in Langston Hughes’ “Mother to Son,” he uses colloquial diction to more clearly portray the character in the poem.

- Symbolism: Symbolism occurs when an author uses an object, character, or event to represent something else in the work. Symbolism is often subtle, it can be unintentional, and it usually adds complexity to the work. For example, a dove often represents peace.

- Irony: Irony is the contrast between appearance/expectation and reality. Irony can be verbal (spoken), situational (something is supposed to happen but doesn’t), or dramatic (difference between what the characters know and what the audience knows).

This song includes many examples of irony…

“Elements of Fiction” created by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed under CC BY NC SA.

Romantic

Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is best known for her novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818, revised 1831). As the daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and early feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, the expectations for Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin were high. Her mother died shortly after her birth, and her father gave her an unconventional education.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is best known for her novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818, revised 1831). As the daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and early feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, the expectations for Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin were high. Her mother died shortly after her birth, and her father gave her an unconventional education.

Mary grew up listening to her father’s guests, who ranged from scientists and philosophers to literary figures such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Mary was sixteen when she fell in love with one of her father’s admirers, the young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (who was estranged from his wife), and ran away with him. The two of them married, several years later, after the death of Shelley’s first wife.

In the summer of 1816, Mary and Percy became the neighbors of Lord Byron, with whom they developed a close friendship while vacationing on the shores of Lake Geneva. During a stretch of bad weather, Byron suggested that each of them should write a ghost story. Mary’s initial idea, which resulted from a nightmare she had, quickly evolved into Frankenstein.

The story of Victor Frankenstein is a cautionary tale of what happens when Romantic ambition and Enlightenment ideals of science and progress are taken too far. This theme also appears in the story of the narrator, the unlucky explorer Robert Walton, who encounters Victor and hears his story. Victor’s most important failure is his abandonment of his Creature, who never receives a name. Victor leaves his initially innocent “child” to survive on his own simply because of his appearance. Although Victor questions whether he himself is to blame for everything that follows, he continues to be repulsed by the Creature’s looks. The impassioned speeches that Mary Shelley writes for the Creature implicitly criticize society for rejecting someone for the wrong reasons. In the end, it is left to the reader to decide whether Victor, the Creature, and/or society in general is the most monstrous.

Shelley also wrote several short stories, of which “The Invisible Girl” is one of the most famous. Click here to read her other short stories.

Introduction to Tales and Stories (1891)

It is customary to regard Mary Shelley’s claims to literary distinction as so entirely rooted and grounded in her husband’s as to constitute a merely parasitic growth upon his fame. It may be unreservedly admitted that her association with Shelley, and her care of his writings and memory after his death, are the strongest of her titles to remembrance. It is further undeniable that the most original of her works is also that which betrays the strongest traces of his influence. Frankenstein was written when her brain, magnetized by his companionship, was capable of an effort never to be repeated. But if the frame of mind which engendered and sustained the work was created by Shelley, the conception was not his, and the diction is dissimilar to his. Both derive from Godwin, but neither is Godwin’s. The same observation, except for an occasional phrase caught from Shelley, applies to all her subsequent work. The frequent exaltation of spirit, the ideality and romance, may well have been Shelley’s—the general style of execution neither repeats nor resembles him.

Mary Shelley’s voice, then, is not to die away as a mere echo of her illustrious husband’s. She has the prima facie claim to a hearing due to every writer who can assert the possession of a distinctive individuality; and if originality be once conceded to Frankenstein, as in all equity it must, none will dispute the validity of a title to fame grounded on such a work. It has solved the question itself—it is famous. It is full of faults venial in an author of nineteen; but, apart from the wild grandeur of the conception, it has that which even the maturity of mere talent never attains—the insight of genius which looks below the appearances of things, and perhaps even reverses its own first conception by the discovery of some underlying truth. Mary Shelley’s original intention was probably that which would alone have occurred to most writers in her place. She meant to paint Frankenstein’s monstrous creation as an object of unmitigated horror. The perception that he was an object of intense compassion as well imparted a moral value to what otherwise would have remained a daring flight of imagination. It has done more: it has helped to create, if it did not itself beget, a type of personage unknown to ancient fiction. The conception of a character at once justly execrable and truly pitiable is altogether modern. Richard the Third and Caliban make some approach towards it; but the former is too self-sufficing in his valour and his villainy to be deeply pitied, and the latter too senseless and brutal. Victor Hugo has made himself the laureate of pathetic deformity, but much of his work is a conscious or unconscious variation on the original theme of Frankenstein.

None of Mary Shelley’s subsequent romances approached Frankenstein in power and popularity. The reason may be summed up in a word—Languor. After the death of her infant son in 1819, she could never again command the energy which had carried her so vigorously through Frankenstein. Except in one instance, her work did not really interest her. Her heart is not in it. Valperga contains many passages of exquisite beauty; but it was, as the authoress herself says, “a child of mighty slow growth;” “laboriously dug,” Shelley adds, “out of a hundred old chronicles,” and wants the fire of imagination which alone could have interpenetrated the mass and fused its diverse ingredients into a satisfying whole. Of the later novels, The Last Man excepted, it is needless to speak, save for the autobiographic interest with which Professor Dowden’s fortunate discovery has informed the hitherto slighted pages of Lodore. But The Last Man demands great attention, for it is not only a work of far higher merit than commonly admitted, but of all her works the most characteristic of the authoress, the most representative of Mary Shelley in the character of pining widowhood which it was her destiny to support for the remainder of her life. It is an idealized version of her sorrows and sufferings, made to contribute a note to the strain which celebrates the final dissolution of the world. The languor which mars her other writings is a beauty here, harmonizing with the general tone of sublime melancholy. Most pictures of the end of the world, painted or penned, have an apocalyptic character. Men’s imaginations are powerfully impressed by great convulsions of nature; fire, tempest, and earthquake are summoned to effect the dissolution of the expiring earth. In The Last Man pestilence is the sole agent, and the tragedy is purely human. The tale consequently lacks the magnificence which the subject might have seemed to invite, but, on the other hand, gains in pathos—a pathos greatly increased when the authoress’s identity is recollected, and it is observed how vividly actual experience traverses her web of fiction. None can have been affected by Mary Shelley’s work so deeply as Mary Shelley herself; for the scenery is that of her familiar haunts, the personages are her intimates under thin disguises, the universal catastrophe is but the magnified image of the overthrow of her own fortunes; and there are pages on pages where every word must have come to her fraught with some unutterably sweet or bitter association. Yet, though her romance could never be to the public what it was to the author, it is surprising that criticism should have hitherto done so little justice either to its pervading nobility of thought or to the eloquence and beauty of very many inspired passages.

When The Last Man is reprinted it will come before the world as a new work. The same is the case with the short tales in this collection, the very existence of which is probably unknown to those most deeply interested in Mary Shelley. The entire class of literature to which they belong has long ago gone into Time’s wallet as “alms for oblivion.” They are exclusively contributions to a form of publication utterly superseded in this hasty age—the Annual, whose very name seemed to prophesy that it would not be perennial. For the creations of the intellect, however, there is a way back from Avernus. Every new generation convicts the last of undue precipitation in discarding the work of its own immediate predecessor. The special literary form may be incapable of revival; but the substance of that which has pleased or profited its age, be it Crashaw’s verse, or Etherege’s comedies, or Hoadly’s pamphlets, or what it may, always repays a fresh examination, and is always found to contribute some element useful or acceptable to the literature of a later day. The day of the “splendid annual” was certainly not a vigorous or healthy one in the history of English belles-lettres. It came in at the ebb of the great tide of poetry which followed on the French Revolution, and before the insetting of the great tide of Victorian prose. A pretentious feebleness characterizes the majority of its productions, half of which are hardly above the level of the album. Yet it had its good points, worthy to be taken into account. The necessary brevity of contributions to an annual operated as a powerful check on the loquacity so unfortunately encouraged by the three-volume novel. There was no room for tiresome descriptions of minutiæ, or interminable talk about uninteresting people. Being, moreover, largely intended for the perusal of high-born maidens in palace towers, the annuals frequently affected an exalted order of sentiment, which, if intolerable in insincere or merely mechanical hands, encouraged the emotion of a really passionate writer as much as the present taste for minute delineation represses it. This perfectly suited Mary Shelley. No writer felt less call to reproduce the society around her. It did not interest her in the smallest degree. The bent of her soul was entirely towards the ideal. This ideal was by no means buried in the grave of Shelley. She aspired passionately towards an imaginary perfection all her life, and solaced disappointment with what, in actual existence, too often proved the parent of fresh disillusion. In fiction it was otherwise; the fashionable style of publication, with all its faults, encouraged the enthusiasm, rapturous or melancholy, with which she adored the present or lamented the lost. She could fully indulge her taste for exalted sentiment in the Annual, and the necessary limitations of space afforded less scope for that creeping languor which relaxed the nerve of her more ambitious productions. In these little tales she is her perfect self, and the reader will find not only the entertainment of interesting fiction, but a fair picture of the mind, repressed in its energies by circumstances, but naturally enthusiastic and aspiring, of a lonely, thwarted, misunderstood woman, who could seldom do herself justice, and whose precise place in the contemporary constellation of genius remains to be determined.

The merit of a collection of stories, casually written at different periods and under different influences, must necessarily be various. As a rule, it may be said that Mary Shelley is best when most ideal, and excels in proportion to the exaltation of the sentiment embodied in her tale. Virtue, patriotism, disinterested affection, are very real things to her; and her heroes and heroines, if generally above the ordinary plane of humanity, never transgress the limits of humanity itself. Her fault is the other way, and arises from a positive incapacity for painting the ugly and the commonplace. She does her best, but her villains do not impress us. Minute delineation of character is never attempted; it lay entirely out of her sphere. Her tales are consequently executed in the free, broad style of the eighteenth century, towards which a reaction is now fortunately observable. As stories, they are very good. The theme is always interesting, and the sequence of events natural. No person and no incident, perhaps, takes a very strong hold upon the imagination; but the general impression is one of a sphere of exalted feeling into which it is good to enter, and which ennobles as much as the photography of ugliness degrades. The diction, as usual in the imaginative literature of the period, is frequently too ornate, and could spare a good many adjectives. But its native strength is revealed in passages of impassioned feeling; and remarkable command over the resources of the language is displayed in descriptions of scenes of natural beauty. The microscopic touch of a Browning or a Meredith, bringing the scene vividly before the mind’s eye, is indeed absolutely wanting; but the landscape is suffused with the poetical atmosphere of a Claude or a Danby. The description at the beginning of The Sisters of Albano is a characteristic and beautiful instance.

The biographical element is deeply interwoven with these as with all Mary Shelley’s writings. It is of especial interest to search out the traces of her own history, and the sources from which her descriptions and ideas may have been derived. The Mourner has evident vestiges of her residence near Windsor when Alastor was written, and probably reflects the general impression derived from Shelley’s recollections of Eton. The visit to Pæstum in The Pole recalls one of the most beautiful of Shelley’s letters, which Mary, however, probably never saw. Claire Clairmont’s fortunes seem glanced at in one or two places; and the story of The Pole may be partly founded on some experience of hers in Russia. Trelawny probably suggested the subjects of the two Greek tales, The Evil Eye, and Euphrasia. The Mortal Immortal is a variation on the theme of St. Leon, and Transformation on that of Frankenstein. These are the only tales in the collection which betray the influence of Godwin, and neither is so fully worked out as it might have been. Mary Shelley was evidently more at home with a human than with a superhuman ideal; her enthusiasm soars high, but does not transcend the possibilities of human nature. The artistic merit of her tales will be diversely estimated, but no reader will refuse the authoress facility of invention, or command of language, or elevation of soul.

-Richard Garnett

“The Invisible Girl”

This slender narrative has no pretensions to the regularity of a story, or the development of situations and feelings; it is but a slight sketch, delivered nearly as it was narrated to me by one of the humblest of the actors concerned: nor will I spin out a circumstance interesting principally from its singularity and truth, but narrate, as concisely as I can, how I was surprised on visiting what seemed a ruined tower, crowning a bleak promontory overhanging the sea, that flows between Wales and Ireland, to find that though the exterior preserved all the savage rudeness that betokened many a war with the elements, the interior was fitted up somewhat in the guise of a summer-house, for it was too small to deserve any other name. It consisted but of the ground-floor, which served as an entrance, and one room above, which was reached by a staircase made out of the thickness of the wall. This chamber was floored and carpeted, decorated with elegant furniture; and, above all, to attract the attention and excite curiosity, there hung over the chimney-piece—for to preserve the apartment from damp a fireplace had been built evidently since it had assumed a guise so dissimilar to the object of its construction—a picture simply painted in water-colours, which deemed more than any part of the adornments of the room to be at war with the rudeness of the building, the solitude in which it was placed, and the desolation of the surrounding scenery. This drawing represented a lovely girl in the very pride and bloom of youth; her dress was simple, in the fashion of the beginning of the eighteenth century; her countenance was embellished by a look of mingled innocence and intelligence, to which was added the imprint of serenity of soul and natural cheerfulness. She was reading one of those folio romances which have so long been the delight of the enthusiastic and young; her mandoline was at her feet—her parroquet perched on a huge mirror near her; the arrangement of furniture and hangings gave token of a luxurious dwelling, and her attire also evidently that of home and privacy, yet bore with it an appearance of ease and girlish ornament, as if she wished to please. Beneath this picture was inscribed in golden letters, “The Invisible Girl.”

Rambling about a country nearly uninhabited, having lost my way, and being overtaken by a shower, I had lighted on this dreary-looking tenement, which seemed to rock in the blast, and to be hung up there as the very symbol of desolation. I was gazing wistfully and cursing inwardly my stars which led me to a ruin that could afford no shelter, though the storm began to pelt more seriously than before, when I saw an old woman’s head popped out from a kind of loophole, and as suddenly withdrawn;—a minute after a feminine voice called to me from within, and penetrating a little brambly maze that screened a door, which I had not before observed, so skilfully had the planter succeeded in concealing art with nature, I found the good dame standing on the threshold and inviting me to take refuge within. “I had just come up from our cot hard by,” she said, “to look after the things, as I do every day, when the rain came on—will ye walk up till it is over?” I was about to observe that the cot hard by, at the venture of a few rain drops, was better than a ruined tower, and to ask my kind hostess whether “the things” were pigeons or crows that she was come to look after, when the matting of the floor and the carpeting of the staircase struck my eye. I was still more surprised when I saw the room above; and beyond all, the picture and its singular inscription, naming her invisible, whom the painter had coloured forth into very agreeable visibility, awakened my most lively curiosity; the result of this, of my exceeding politeness towards the old woman, and her own natural garrulity, was a kind of garbled narrative which my imagination eked out, and future inquiries rectified, till it assumed the following form.

Some years before, in the afternoon of a September day, which, though tolerably fair, gave many tokens of a tempestuous night, a gentleman arrived at a little coast town about ten miles from this place; he expressed his desire to hire a boat to carry him to the town of —— about fifteen miles farther on the coast. The menaces which the sky held forth made the fishermen loathe to venture, till at length two, one the father of a numerous family, bribed by the bountiful reward the stranger promised, the other, the son of my hostess, induced by youthful daring, agreed to undertake the voyage. The wind was fair, and they hoped to make good way before nightfall, and to get into port ere the rising of the storm. They pushed off with good cheer, at least the fishermen did; as for the stranger, the deep mourning which he wore was not half so black as the melancholy that wrapt his mind. He looked as if he had never smiled—as if some unutterable thought, dark as night and bitter as death, had built its nest within his bosom, and brooded therein eternally; he did not mention his name; but one of the villagers recognised him as Henry Vernon, the son of a baronet who possessed a mansion about three miles distant from the town for which he was bound. This mansion was almost abandoned by the family; but Henry had, in a romantic fit, visited it about three years before, and Sir Peter had been down there during the previous spring for about a couple of months.

The boat did not make so much way as was expected; the breeze failed them as they got out to sea, and they were fain with oar as well as sail to try to weather the promontory that jutted out between them and the spot they desired to reach. They were yet far distant when the shifting wind began to exert its strength, and to blow with violent though unequal blasts. Night came on pitchy dark, and the howling waves rose and broke with frightful violence, menacing to overwhelm the tiny bark that dared resist their fury. They were forced to lower every sail, and take to their oars; one man was obliged to bale out the water, and Vernon himself took an oar, and rowing with desperate energy, equalled the force of the more practised boatmen. There had been much talk between the sailors before the tempest came on; now, except a brief command, all were silent. One thought of his wife and children, and silently cursed the caprice of the stranger that endangered in its effects, not only his life, but their welfare; the other feared less, for he was a daring lad, but he worked hard, and had no time for speech; while Vernon bitterly regretting the thoughtlessness which had made him cause others to share a peril, unimportant as far as he himself was concerned, now tried to cheer them with a voice full of animation and courage, and now pulled yet more strongly at the oar he held. The only person who did not seem wholly intent on the work he was about, was the man who baled; every now and then he gazed intently round, as if the sea held afar off, on its tumultuous waste, some object that he strained his eyes to discern. But all was blank, except as the crests of the high waves showed themselves, or far out on the verge of the horizon, a kind of lifting of the clouds betokened greater violence for the blast. At length he exclaimed, “Yes, I see it!—the larboard oar!—now! if we can make yonder light, we are saved!” Both the rowers instinctively turned their heads,—but cheerless darkness answered their gaze.

“You cannot see it,” cried their companion, “but we are nearing it; and, please God, we shall outlive this night.” Soon he took the oar from Vernon’s hand, who, quite exhausted, was failing in his strokes. He rose and looked for the beacon which promised them safety;—it glimmered with so faint a ray, that now he said, “I see it;” and again, “it is nothing:” still, as they made way, it dawned upon his sight, growing more steady and distinct as it beamed across the lurid waters, which themselves became smoother, so that safety seemed to arise from the bosom of the ocean under the influence of that flickering gleam.

“What beacon is it that helps us at our need?” asked Vernon, as the men, now able to manage their oars with greater ease, found breath to answer his question.

“A fairy one, I believe,” replied the elder sailor, “yet no less a true: it burns in an old tumble-down tower, built on the top of a rock which looks over the sea. We never saw it before this summer; and now each night it is to be seen,—at least when it is looked for, for we cannot see it from our village;—and it is such an out-of-the-way place that no one has need to go near it, except through a chance like this. Some say it is burnt by witches, some say by smugglers; but this I know, two parties have been to search, and found nothing but the bare walls of the tower. All is deserted by day, and dark by night; for no light was to be seen while we were there, though it burned sprightly enough when we were out at sea.”

“I have heard say,” observed the younger sailor, “it is burnt by the ghost of a maiden who lost her sweetheart in these parts; he being wrecked, and his body found at the foot of the tower: she goes by the name among us of the ‘Invisible Girl.’”

The voyagers had now reached the landing-place at the foot of the tower. Vernon cast a glance upward,—the light was still burning. With some difficulty, struggling with the breakers, and blinded by night, they contrived to get their little bark to shore, and to draw her up on the beach. They then scrambled up the precipitous pathway, overgrown by weeds and underwood, and, guided by the more experienced fisherman, they found the entrance to the tower; door or gate there was none, and all was dark as the tomb, and silent and almost as cold as death.

“This will never do,” said Vernon; “surely our hostess will show her light, if not herself, and guide our darkling steps by some sign of life and comfort.”

“We will get to the upper chamber,” said the sailor, “if I can but hit upon the broken-down steps; but you will find no trace of the Invisible Girl nor her light either, I warrant.”

“Truly a romantic adventure of the most disagreeable kind,” muttered Vernon, as he stumbled over the unequal ground; “she of the beacon-light must be both ugly and old, or she would not be so peevish and inhospitable.”

With considerable difficulty, and after divers knocks and bruises, the adventurers at length succeeded in reaching the upper storey; but all was blank and bare, and they were fain to stretch themselves on the hard floor, when weariness, both of mind and body, conduced to steep their senses in sleep.

Long and sound were the slumbers of the mariners. Vernon but forgot himself for an hour; then throwing off drowsiness, and finding his rough couch uncongenial to repose, he got up and placed himself at the hole that served for a window—for glass there was none, and there being not even a rough bench, he leant his back against the embrasure, as the only rest he could find. He had forgotten his danger, the mysterious beacon, and its invisible guardian: his thoughts were occupied on the horrors of his own fate, and the unspeakable wretchedness that sat like a nightmare on his heart.

It would require a good-sized volume to relate the causes which had changed the once happy Vernon into the most woful mourner that ever clung to the outer trappings of grief, as slight though cherished symbols of the wretchedness within. Henry was the only child of Sir Peter Vernon, and as much spoiled by his father’s idolatry as the old baronet’s violent and tyrannical temper would permit. A young orphan was educated in his father’s house, who in the same way was treated with generosity and kindness, and yet who lived in deep awe of Sir Peter’s authority, who was a widower; and these two children were all he had to exert his power over, or to whom to extend his affection. Rosina was a cheerful-tempered girl, a little timid, and careful to avoid displeasing her protector; but so docile, so kind-hearted, and so affectionate, that she felt even less than Henry the discordant spirit of his parent. It is a tale often told; they were playmates and companions in childhood, and lovers in after days. Rosina was frightened to imagine that this secret affection, and the vows they pledged, might be disapproved of by Sir Peter. But sometimes she consoled herself by thinking that perhaps she was in reality her Henry’s destined bride, brought up with him under the design of their future union; and Henry, while he felt that this was not the case, resolved to wait only until he was of age to declare and accomplish his wishes in making the sweet Rosina his wife. Meanwhile he was careful to avoid premature discovery of his intentions, so to secure his beloved girl from persecution and insult. The old gentleman was very conveniently blind; he lived always in the country, and the lovers spent their lives together, unrebuked and uncontrolled. It was enough that Rosina played on her mandoline, and sang Sir Peter to sleep every day after dinner; she was the sole female in the house above the rank of a servant, and had her own way in the disposal of her time. Even when Sir Peter frowned, her innocent caresses and sweet voice were powerful to smooth the rough current of his temper. If ever human spirit lived in an earthly paradise, Rosina did at this time: her pure love was made happy by Henry’s constant presence; and the confidence they felt in each other, and the security with which they looked forward to the future, rendered their path one of roses under a cloudless sky. Sir Peter was the slight drawback that only rendered their tête-à-tête more delightful, and gave value to the sympathy they each bestowed on the other. All at once an ominous personage made its appearance in Vernon Place, in the shape of a widow sister of Sir Peter, who, having succeeded in killing her husband and children with the effects of her vile temper, came, like a harpy, greedy for new prey, under her brother’s roof. She too soon detected the attachment of the unsuspicious pair. She made all speed to impart her discovery to her brother, and at once to restrain and inflame his rage. Through her contrivance Henry was suddenly despatched on his travels abroad, that the coast might be clear for the persecution of Rosina; and then the richest of the lovely girl’s many admirers, whom, under Sir Peter’s single reign, she was allowed, nay, almost commanded, to dismiss, so desirous was he of keeping her for his own comfort, was selected, and she was ordered to marry him. The scenes of violence to which she was now exposed, the bitter taunts of the odious Mrs. Bainbridge, and the reckless fury of Sir Peter, were the more frightful and overwhelming from their novelty. To all she could only oppose a silent, tearful, but immutable steadiness of purpose: no threats, no rage could extort from her more than a touching prayer that they would not hate her, because she could not obey.

“There must be something we don’t see under all this,” said Mrs. Bainbridge; “take my word for it, brother, she corresponds secretly with Henry. Let us take her down to your seat in Wales, where she will have no pensioned beggars to assist her; and we shall see if her spirit be not bent to our purpose.”

Sir Peter consented, and they all three took up their abode in the solitary and dreary-looking house before alluded to as belonging to the family. Here poor Rosina’s sufferings grew intolerable. Before, surrounded by well-known scenes, and in perpetual intercourse with kind and familiar faces, she had not despaired in the end of conquering by her patience the cruelty of her persecutors;—nor had she written to Henry, for his name had not been mentioned by his relatives, nor their attachment alluded to, and she felt an instinctive wish to escape the dangers about her without his being annoyed, or the sacred secret of her love being laid bare, and wronged by the vulgar abuse of his aunt or the bitter curses of his father. But when she was taken to Wales, and made a prisoner in her apartment, when the flinty mountains about her seemed feebly to imitate the stony hearts she had to deal with, her courage began to fail. The only attendant permitted to approach her was Mrs. Bainbridge’s maid; and under the tutelage of her fiend-like mistress, this woman was used as a decoy to entice the poor prisoner into confidence, and then to be betrayed. The simple, kind-hearted Rosina was a facile dupe, and at last, in the excess of her despair, wrote to Henry, and gave the letter to this woman to be forwarded. The letter in itself would have softened marble; it did not speak of their mutual vows, it but asked him to intercede with his father, that he would restore her to the place she had formerly held in his affections, and cease from a cruelty that would destroy her. “For I may die,” wrote the hapless girl, “but marry another—never!” That single word, indeed, had sufficed to betray her secret, had it not been already discovered; as it was, it gave increased fury to Sir Peter, as his sister triumphantly pointed it out to him, for it need hardly be said that while the ink of the address was yet wet, and the seal still warm, Rosina’s letter was carried to this lady. The culprit was summoned before them. What ensued none could tell; for their own sakes the cruel pair tried to palliate their part. Voices were high, and the soft murmur of Rosina’s tone was lost in the howling of Sir Peter and the snarling of his sister. “Out of doors you shall go,” roared the old man; “under my roof you shall not spend another night.” And the words infamous seductress, and worse, such as had never met the poor girl’s ear before, were caught by listening servants; and to each angry speech of the baronet, Mrs. Bainbridge added an envenomed point worse than all.

More dead then alive, Rosina was at last dismissed. Whether guided by despair, whether she took Sir Peter’s threats literally, or whether his sister’s orders were more decisive, none knew, but Rosina left the house; a servant saw her cross the park, weeping, and wringing her hands as she went. What became of her none could tell; her disappearance was not disclosed to Sir Peter till the following day, and then he showed by his anxiety to trace her steps and to find her, that his words had been but idle threats. The truth was, that though Sir Peter went to frightful lengths to prevent the marriage of the heir of his house with the portionless orphan, the object of his charity, yet in his heart he loved Rosina, and half his violence to her rose from anger at himself for treating her so ill. Now remorse began to sting him, as messenger after messenger came back without tidings of his victim. He dared not confess his worst fears to himself; and when his inhuman sister, trying to harden her conscience by angry words, cried, “The vile hussy has too surely made away with herself out of revenge to us,” an oath the most tremendous, and a look sufficient to make even her tremble, commanded her silence. Her conjecture, however, appeared too true: a dark and rushing stream that flowed at the extremity of the park had doubtless received the lovely form, and quenched the life of this unfortunate girl. Sir Peter, when his endeavours to find her proved fruitless, returned to town, haunted by the image of his victim, and forced to acknowledge in his own heart that he would willingly lay down his life, could he see her again, even though it were as the bride of his son—his son, before whose questioning he quailed like the veriest coward; for when Henry was told of the death of Rosina, he suddenly returned from abroad to ask the cause—to visit her grave, and mourn her loss in the groves and valleys which had been the scenes of their mutual happiness. He made a thousand inquiries, and an ominous silence alone replied. Growing more earnest and more anxious, at length he drew from servants and dependents, and his odious aunt herself, the whole dreadful truth. From that moment despair struck his heart, and misery named him her own. He fled from his father’s presence; and the recollection that one whom he ought to revere was guilty of so dark a crime, haunted him, as of old the Eumenides tormented the souls of men given up to their torturings. His first, his only wish, was to visit Wales, and to learn if any new discovery had been made, and whether it were possible to recover the mortal remains of the lost Rosina, so to satisfy the unquiet longings of his miserable heart. On this expedition was he bound when he made his appearance at the village before named; and now, in the deserted tower, his thoughts were busy with images of despair and death, and what his beloved one had suffered before her gentle nature had been goaded to such a deed of woe.

While immersed in gloomy reverie, to which the monotonous roaring of the sea made fit accompaniment, hours flew on, and Vernon was at last aware that the light of morning was creeping from out its eastern retreat, and dawning over the wild ocean, which still broke in furious tumult on the rocky beach. His companions now roused themselves, and prepared to depart. The food they had brought with them was damaged by sea-water, and their hunger, after hard labour and many hours’ fasting, had become ravenous. It was impossible to put to sea in their shattered boat; but there stood a fisher’s cot about two miles off, in a recess in the bay, of which the promontory on which the tower stood formed one side; and to this they hastened to repair. They did not spend a second thought on the light which had saved them, nor its cause, but left the ruin in search of a more hospitable asylum. Vernon cast his eyes round as he quitted it, but no vestige of an inhabitant met his eye, and he began to persuade himself that the beacon had been a creation of fancy merely. Arriving at the cottage in question, which was inhabited by a fisherman and his family, they made a homely breakfast, and then prepared to return to the tower, to refit their boat, and, if possible, bring her round. Vernon accompanied them, together with their host and his son. Several questions were asked concerning the Invisible Girl and her light, each agreeing that the apparition was novel, and not one being able to give even an explanation of how the name had become affixed to the unknown cause of this singular appearance; though both of the men of the cottage affirmed that once or twice they had seen a female figure in the adjacent wood, and that now and then a stranger girl made her appearance at another cot a mile off, on the other side of the promontory, and bought bread; they suspected both these to be the same, but could not tell. The inhabitants of the cot, indeed, appeared too stupid even to feel curiosity, and had never made any attempt at discovery. The whole day was spent by the sailors in repairing the boat; and the sound of hammers, and the voices of the men at work, resounded along the coast, mingled with the dashing of the waves. This was no time to explore the ruin for one who, whether human or supernatural, so evidently withdrew herself from intercourse with every living being. Vernon, however, went over the tower, and searched every nook in vain. The dingy bare walls bore no token of serving as a shelter; and even a little recess in the wall of the staircase, which he had not before observed, was equally empty and desolate. Quitting the tower, he wandered in the pine wood that surrounded it, and, giving up all thought of solving the mystery, was soon engrossed by thoughts that touched his heart more nearly, when suddenly there appeared on the ground at his feet the vision of a slipper. Since Cinderella so tiny a slipper had never been seen; as plain as shoe could speak, it told a tale of elegance, loveliness, and youth. Vernon picked it up. He had often admired Rosina’s singularly small foot, and his first thought was a question whether this little slipper would have fitted it. It was very strange!—it must belong to the Invisible Girl. Then there was a fairy form that kindled that light—a form of such material substance that its foot needed to be shod; and yet how shod?—with kid so fine, and of shape so exquisite, that it exactly resembled such as Rosina wore! Again the recurrence of the image of the beloved dead came forcibly across him; and a thousand home-felt associations, childish yet sweet, and lover-like though trifling, so filled Vernon’s heart, that he threw himself his length on the ground, and wept more bitterly than ever the miserable fate of the sweet orphan.

In the evening the men quitted their work, and Vernon returned with them to the cot where they were to sleep, intending to pursue their voyage, weather permitting, the following morning. Vernon said nothing of his slipper, but returned with his rough associates. Often he looked back; but the tower rose darkly over the dim waves, and no light appeared. Preparations had been made in the cot for their accommodation, and the only bed in it was offered Vernon; but he refused to deprive his hostess, and, spreading his cloak on a heap of dry leaves, endeavoured to give himself up to repose. He slept for some hours; and when he awoke, all was still, save that the hard breathing of the sleepers in the same room with him interrupted the silence. He rose, and, going to the window, looked out over the now placid sea towards the mystic tower. The light was burning there, sending its slender rays across the waves. Congratulating himself on a circumstance he had not anticipated, Vernon softly left the cottage, and, wrapping his cloak round him, walked with a swift pace round the bay towards the tower. He reached it; still the light was burning. To enter and restore the maiden her shoe, would be but an act of courtesy; and Vernon intended to do this with such caution as to come unaware, before its wearer could, with her accustomed arts, withdraw herself from his eyes; but, unluckily, while yet making his way up the narrow pathway, his foot dislodged a loose fragment, that fell with crash and sound down the precipice. He sprung forward, on this, to retrieve by speed the advantage he had lost by this unlucky accident. He reached the door; he entered: all was silent, but also all was dark. He paused in the room below; he felt sure that a slight sound met his ear. He ascended the steps, and entered the upper chamber; but blank obscurity met his penetrating gaze, the starless night admitted not even a twilight glimmer through the only aperture. He closed his eyes, to try, on opening them again, to be able to catch some faint, wandering ray on the visual nerve; but it was in vain. He groped round the room; he stood still, and held his breath; and then, listening intently, he felt sure that another occupied the chamber with him, and that its atmosphere was slightly agitated by another’s respiration. He remembered the recess in the staircase; but before he approached it he spoke;—he hesitated a moment what to say. “I must believe,” he said, “that misfortune alone can cause your seclusion; and if the assistance of a man—of a gentleman”—

An exclamation interrupted him; a voice from the grave spoke his name—the accents of Rosina syllabled, “Henry!—is it indeed Henry whom I hear?”

He rushed forward, directed by the sound, and clasped in his arms the living form of his own lamented girl—his own Invisible Girl he called her; for even yet, as he felt her heart beat near his, and as he entwined her waist with his arm, supporting her as she almost sank to the ground with agitation, he could not see her; and, as her sobs prevented her speech, no sense but the instinctive one that filled his heart with tumultuous gladness, told him that the slender, wasted form he pressed so fondly was the living shadow of the Hebe beauty he had adored.

The morning saw this pair thus strangely restored to each other on the tranquil sea, sailing with a fair wind for L——, whence they were to proceed to Sir Peter’s seat, which, three months before, Rosina had quitted in such agony and terror. The morning light dispelled the shadows that had veiled her, and disclosed the fair person of the Invisible Girl. Altered indeed she was by suffering and woe, but still the same sweet smile played on her lips, and the tender light of her soft blue eyes were all her own. Vernon drew out the slipper, and showed the cause that had occasioned him to resolve to discover the guardian of the mystic beacon; even now he dared not inquire how she had existed in that desolate spot, or wherefore she had so sedulously avoided observation, when the right thing to have been done was to have sought him immediately, under whose care, protected by whose love, no danger need be feared. But Rosina shrunk from him as he spoke, and a deathlike pallor came over her cheek, as she faintly whispered, “Your father’s curse—your father’s dreadful threats!” It appeared, indeed, that Sir Peter’s violence, and the cruelty of Mrs. Bainbridge, had succeeded in impressing Rosina with wild and unvanquishable terror. She had fled from their house without plan or forethought—driven by frantic horror and overwhelming fear, she had left it with scarcely any money, and there seemed to her no possibility of either returning or proceeding onward. She had no friend except Henry in the wide world; whither could she go?—to have sought Henry would have sealed their fates to misery; for, with an oath, Sir Peter had declared he would rather see them both in their coffins than married. After wandering about, hiding by day, and only venturing forth at night, she had come to this deserted tower, which seemed a place of refuge. How she had lived since then she could hardly tell: she had lingered in the woods by day, or slept in the vault of the tower, an asylum none were acquainted with or had discovered: by night she burned the pinecones of the wood, and night was her dearest time; for it seemed to her as if security came with darkness. She was unaware that Sir Peter had left that part of the country, and was terrified lest her hiding-place should be revealed to him. Her only hope was that Henry would return—that Henry would never rest till he had found her. She confessed that the long interval and the approach of winter had visited her with dismay; she feared that, as her strength was failing, and her form wasting to a skeleton, that she might die, and never see her own Henry more.

An illness, indeed, in spite of all his care, followed her restoration to security and the comforts of civilised life; many months went by before the bloom revisiting her cheeks, and her limbs regaining their roundness, she resembled once more the picture drawn of her in her days of bliss before any visitation of sorrow. It was a copy of this portrait that decorated the tower, the scene of her suffering, in which I had found shelter. Sir Peter, overjoyed to be relieved from the pangs of remorse, and delighted again to see his orphan ward, whom he really loved, was now as eager as before he had been averse to bless her union with his son. Mrs. Bainbridge they never saw again. But each year they spent a few months in their Welsh mansion, the scene of their early wedded happiness, and the spot where again poor Rosina had awoke to life and joy after her cruel persecutions. Henry’s fond care had fitted up the tower, and decorated it as I saw; and often did he come over, with his “Invisible Girl,” to renew, in the very scene of its occurrence, the remembrance of all the incidents which had led to their meeting again, during the shades of night, in that sequestered ruin.

- “The Invisible Girl” is licensed under Public Domain.

- “Mary Shelley” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II: Volume 5 and licensed under CC BY SA.

Realist

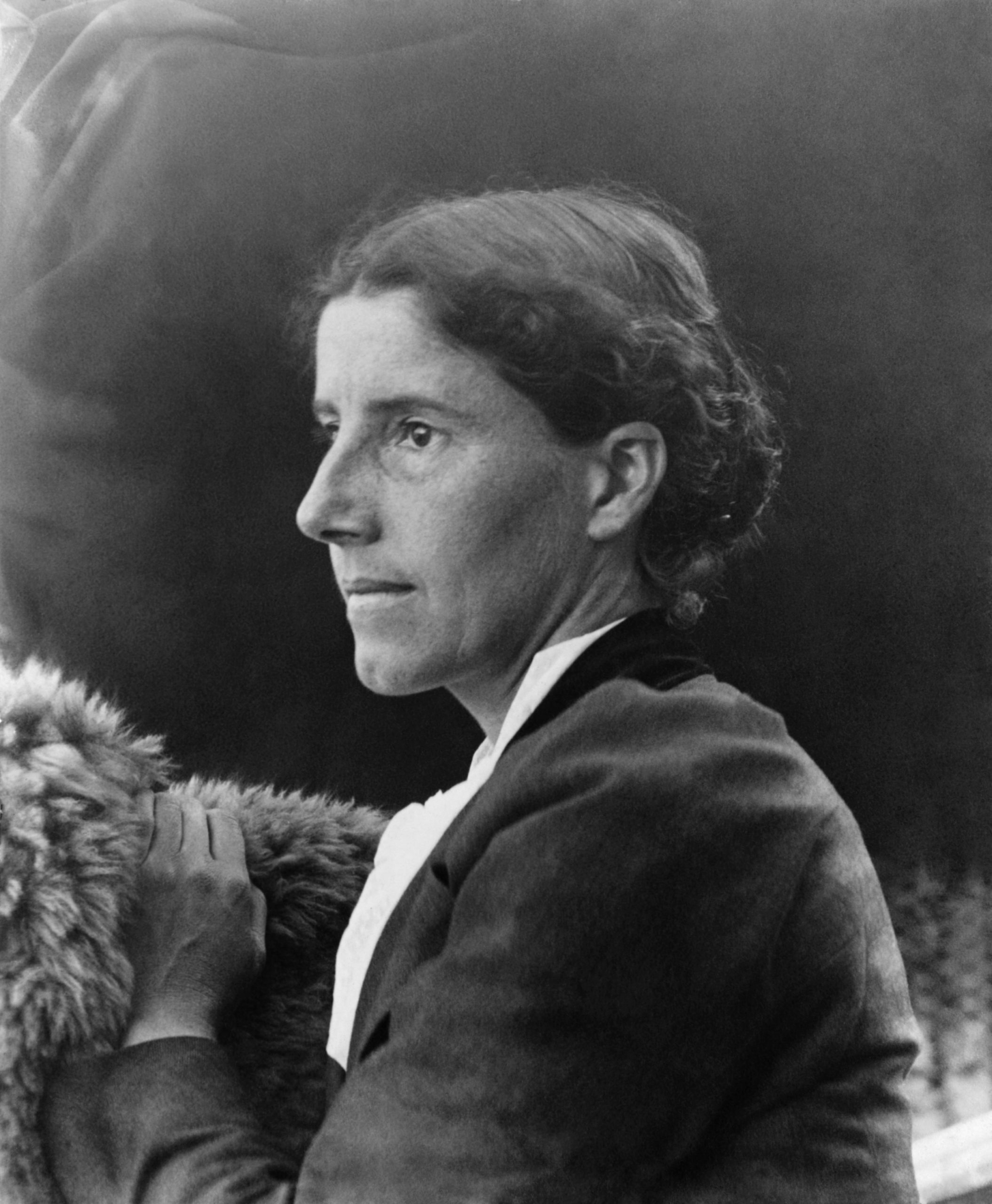

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman made a name for herself as a feminist writer, a suffragist, and a lecturer on social issues. Although her father, Frederick Beecher Perkins, walked out on his family when she was a baby, Gilman spent time with her father’s aunts: Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Isabella Beecher Hooker (a suffragist), and Catherine Beecher (an educator and advocate for female education).

Charlotte Perkins Gilman made a name for herself as a feminist writer, a suffragist, and a lecturer on social issues. Although her father, Frederick Beecher Perkins, walked out on his family when she was a baby, Gilman spent time with her father’s aunts: Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Isabella Beecher Hooker (a suffragist), and Catherine Beecher (an educator and advocate for female education).

Gilman argued that fundamental changes in society were necessary for women to achieve equality. In Women and Economics (1898), Gilman noted that women would be more independent when tasks such as cooking and cleaning could be (to use a modern term) outsourced, allowing women to work outside of the home. Gilman lectured extensively on a variety of social issues, worked as a magazine editor, and published novels, short stories, collections of poetry, works on sociology, and numerous articles.

She was married twice; the second marriage was a happy one, while an incident from the first (unhappy) marriage inspired her most famous work, “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892). After the birth of her only child, Gilman suffered from postpartum depression; with her husband’s support, a doctor called it hysteria and prescribed what was called the rest cure treatment, which involved being kept in seclusion with nothing to do (since she was forbidden to write or paint). The treatment only worsened her depression, which only improved when she became active again, and the experience ultimately resulted in a divorce. The story is partly autobiographical (although Gilman did not deteriorate to the extent that her character does) and examines how society damages a woman’s mental and physical health by denying her the freedom she needs.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman explains why she wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper” here.

A video of “The Yellow Wallpaper”:

“The Yellow Wallpaper”

It is very seldom that mere ordinary people like John and myself secure ancestral halls for the summer.

A colonial mansion, a hereditary estate, I would say a haunted house, and reach the height of romantic felicity—but that would be asking too much of fate!

Still I will proudly declare that there is something queer about it.

Else, why should it be let so cheaply? And why have stood so long untenanted?

John laughs at me, of course, but one expects that in marriage.

John is practical in the extreme. He has no patience with faith, an intense horror of superstition, and he scoffs openly at any talk of things not to be felt and seen and put down in figures.

John is a physician, and perhaps—(I would not say it to a living soul, of course, but this is dead paper and a great relief to my mind)—perhaps that is one reason I do not get well faster.

You see, he does not believe I am sick!

And what can one do?

If a physician of high standing, and one’s own husband, assures friends and relatives that there is really nothing the matter with one but temporary nervous depression—a slight hysterical tendency—what is one to do?

My brother is also a physician, and also of high standing, and he says the same thing.

So I take phosphates or phosphites—whichever it is, and tonics, and journeys, and air, and exercise, and am absolutely forbidden to “work” until I am well again.

Personally, I disagree with their ideas.

Personally, I believe that congenial work, with excitement and change, would do me good.

But what is one to do?

I did write for a while in spite of them; but it does exhaust me a good deal—having to be so sly about it, or else meet with heavy opposition.

I sometimes fancy that in my condition if I had less opposition and more society and stimulus—but John says the very worst thing I can do is to think about my condition, and I confess it always makes me feel bad.

So I will let it alone and talk about the house.

The most beautiful place! It is quite alone, standing well back from the road, quite three miles from the village. It makes me think of English places that you read about, for there are hedges and walls and gates that lock, and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people.

There is a delicious garden! I never saw such a garden—large and shady, full of box-bordered paths, and lined with long grape-covered arbors with seats under them.

There were greenhouses, too, but they are all broken now.

There was some legal trouble, I believe, something about the heirs and co-heirs; anyhow, the place has been empty for years.

That spoils my ghostliness, I am afraid; but I don’t care—there is something strange about the house—I can feel it.

I even said so to John one moonlight evening, but he said what I felt was a draught, and shut the window.

I get unreasonably angry with John sometimes. I’m sure I never used to be so sensitive. I think it is due to this nervous condition.

But John says if I feel so I shall neglect proper self-control; so I take pains to control myself,—before him, at least,—and that makes me very tired.

I don’t like our room a bit. I wanted one downstairs that opened on the piazza and had roses all over the window, and such pretty old-fashioned chintz hangings! but John would not hear of it.

He said there was only one window and not room for two beds, and no near room for him if he took another.

He is very careful and loving, and hardly lets me stir without special direction.

I have a schedule prescription for each hour in the day; he takes all care from me, and so I feel basely ungrateful not to value it more.

He said we came here solely on my account, that I was to have perfect rest and all the air I could get. “Your exercise depends on your strength, my dear,” said he, “and your food somewhat on your appetite; but air you can absorb all the time.” So we took the nursery, at the top of the house.

It is a big, airy room, the whole floor nearly, with windows that look all ways, and air and sunshine galore. It was nursery first and then playground and gymnasium, I should judge; for the windows are barred for little children, and there are rings and things in the walls.

The paint and paper look as if a boys’ school had used it. It is stripped off—the paper—in great patches all around the head of my bed, about as far as I can reach, and in a great place on the other side of the room low down. I never saw a worse paper in my life.

One of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin.

It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate, and provoke study, and when you follow the lame, uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide—plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard-of contradictions.

The color is repellant, almost revolting; a smouldering, unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight.

It is a dull yet lurid orange in some places, a sickly sulphur tint in others.

No wonder the children hated it! I should hate it myself if I had to live in this room long.

There comes John, and I must put this away,—he hates to have me write a word.

We have been here two weeks, and I haven’t felt like writing before, since that first day.

I am sitting by the window now, up in this atrocious nursery, and there is nothing to hinder my writing as much as I please, save lack of strength.

John is away all day, and even some nights when his cases are serious.

I am glad my case is not serious!

But these nervous troubles are dreadfully depressing.

John does not know how much I really suffer. He knows there is no reason to suffer, and that satisfies him.

Of course it is only nervousness. It does weigh on me so not to do my duty in any way!

I meant to be such a help to John, such a real rest and comfort, and here I am a comparative burden already!

Nobody would believe what an effort it is to do what little I am able—to dress and entertain, and order things.

It is fortunate Mary is so good with the baby. Such a dear baby!

And yet I cannot be with him, it makes me so nervous.

I suppose John never was nervous in his life. He laughs at me so about this wallpaper!

At first he meant to repaper the room, but afterwards he said that I was letting it get the better of me, and that nothing was worse for a nervous patient than to give way to such fancies.

He said that after the wallpaper was changed it would be the heavy bedstead, and then the barred windows, and then that gate at the head of the stairs, and so on.

“You know the place is doing you good,” he said, “and really, dear, I don’t care to renovate the house just for a three months’ rental.”

“Then do let us go downstairs,” I said, “there are such pretty rooms there.”

Then he took me in his arms and called me a blessed little goose, and said he would go down cellar if I wished, and have it whitewashed into the bargain.

But he is right enough about the beds and windows and things.

It is as airy and comfortable a room as any one need wish, and, of course, I would not be so silly as to make him uncomfortable just for a whim.

I’m really getting quite fond of the big room, all but that horrid paper.

Out of one window I can see the garden, those mysterious deep-shaded arbors, the riotous old-fashioned flowers, and bushes and gnarly trees.

Out of another I get a lovely view of the bay and a little private wharf belonging to the estate. There is a beautiful shaded lane that runs down there from the house. I always fancy I see people walking in these numerous paths and arbors, but John has cautioned me not to give way to fancy in the least. He says that with my imaginative power and habit of story-making a nervous weakness like mine is sure to lead to all manner of excited fancies, and that I ought to use my will and good sense to check the tendency. So I try.

I think sometimes that if I were only well enough to write a little it would relieve the press of ideas and rest me.

But I find I get pretty tired when I try.

It is so discouraging not to have any advice and companionship about my work. When I get really well John says we will ask Cousin Henry and Julia down for a long visit; but he says he would as soon put fire-works in my pillow-case as to let me have those stimulating people about now.

I wish I could get well faster.

But I must not think about that. This paper looks to me as if it knew what a vicious influence it had!

There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck and two bulbous eyes stare at you upside-down.

I get positively angry with the impertinence of it and the everlastingness. Up and down and sideways they crawl, and those absurd, unblinking eyes are everywhere. There is one place where two breadths didn’t match, and the eyes go all up and down the line, one a little higher than the other.

I never saw so much expression in an inanimate thing before, and we all know how much expression they have! I used to lie awake as a child and get more entertainment and terror out of blank walls and plain furniture than most children could find in a toy-store.

I remember what a kindly wink the knobs of our big old bureau used to have, and there was one chair that always seemed like a strong friend.

I used to feel that if any of the other things looked too fierce I could always hop into that chair and be safe.

The furniture in this room is no worse than inharmonious, however, for we had to bring it all from downstairs. I suppose when this was used as a playroom they had to take the nursery things out, and no wonder! I never saw such ravages as the children have made here.

The wallpaper, as I said before, is torn off in spots, and it sticketh closer than a brother—they must have had perseverance as well as hatred.

Then the floor is scratched and gouged and splintered, the plaster itself is dug out here and there, and this great heavy bed, which is all we found in the room, looks as if it had been through the wars.

But I don’t mind it a bit—only the paper.

There comes John’s sister. Such a dear girl as she is, and so careful of me! I must not let her find me writing.

She is a perfect, and enthusiastic housekeeper, and hopes for no better profession. I verily believe she thinks it is the writing which made me sick!

But I can write when she is out, and see her a long way off from these windows.

There is one that commands the road, a lovely, shaded, winding road, and one that just looks off over the country. A lovely country, too, full of great elms and velvet meadows.

This wallpaper has a kind of sub-pattern in a different shade, a particularly irritating one, for you can only see it in certain lights, and not clearly then.

But in the places where it isn’t faded, and where the sun is just so, I can see a strange, provoking, formless sort of figure, that seems to sulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design.

There’s sister on the stairs!

Well, the Fourth of July is over! The people are gone and I am tired out. John thought it might do me good to see a little company, so we just had mother and Nellie and the children down for a week.

Of course I didn’t do a thing. Jennie sees to everything now.

But it tired me all the same.

John says if I don’t pick up faster he shall send me to Weir Mitchell in the fall.

But I don’t want to go there at all. I had a friend who was in his hands once, and she says he is just like John and my brother, only more so!

Besides, it is such an undertaking to go so far.

I don’t feel as if it was worth while to turn my hand over for anything, and I’m getting dreadfully fretful and querulous.

I cry at nothing, and cry most of the time.

Of course I don’t when John is here, or anybody else, but when I am alone.

And I am alone a good deal just now. John is kept in town very often by serious cases, and Jennie is good and lets me alone when I want her to.

So I walk a little in the garden or down that lovely lane, sit on the porch under the roses, and lie down up here a good deal.

I’m getting really fond of the room in spite of the wallpaper. Perhaps because of the wallpaper.

It dwells in my mind so!

I lie here on this great immovable bed—it is nailed down, I believe—and follow that pattern about by the hour. It is as good as gymnastics, I assure you. I start, we’ll say, at the bottom, down in the corner over there where it has not been touched, and I determine for the thousandth time that I will follow that pointless pattern to some sort of a conclusion.

I know a little of the principle of design, and I know this thing was not arranged on any laws of radiation, or alternation, or repetition, or symmetry, or anything else that I ever heard of.

It is repeated, of course, by the breadths, but not otherwise.

Looked at in one way each breadth stands alone, the bloated curves and flourishes—a kind of “debased Romanesque” with delirium tremens—go waddling up and down in isolated columns of fatuity.

But, on the other hand, they connect diagonally, and the sprawling outlines run off in great slanting waves of optic horror, like a lot of wallowing seaweeds in full chase.

The whole thing goes horizontally, too, at least it seems so, and I exhaust myself in trying to distinguish the order of its going in that direction.

They have used a horizontal breadth for a frieze, and that adds wonderfully to the confusion.

There is one end of the room where it is almost intact, and there, when the cross-lights fade and the low sun shines directly upon it, I can almost fancy radiation after all,—the interminable grotesques seem to form around a common centre and rush off in headlong plunges of equal distraction.

It makes me tired to follow it. I will take a nap, I guess.

I don’t know why I should write this.

I don’t want to.

I don’t feel able.

And I know John would think it absurd. But I must say what I feel and think in some way—it is such a relief!

But the effort is getting to be greater than the relief.

Half the time now I am awfully lazy, and lie down ever so much.

John says I musn’t lose my strength, and has me take cod-liver oil and lots of tonics and things, to say nothing of ale and wine and rare meat.

Dear John! He loves me very dearly, and hates to have me sick. I tried to have a real earnest reasonable talk with him the other day, and tell him how I wish he would let me go and make a visit to Cousin Henry and Julia.

But he said I wasn’t able to go, nor able to stand it after I got there; and I did not make out a very good case for myself, for I was crying before I had finished.

It is getting to be a great effort for me to think straight. Just this nervous weakness, I suppose.

And dear John gathered me up in his arms, and just carried me upstairs and laid me on the bed, and sat by me and read to me till it tired my head.

He said I was his darling and his comfort and all he had, and that I must take care of myself for his sake, and keep well.

He says no one but myself can help me out of it, that I must use my will and self-control and not let any silly fancies run away with me.

There’s one comfort, the baby is well and happy, and does not have to occupy this nursery with the horrid wallpaper.

If we had not used it that blessed child would have! What a fortunate escape! Why, I wouldn’t have a child of mine, an impressionable little thing, live in such a room for worlds.

I never thought of it before, but it is lucky that John kept me here after all. I can stand it so much easier than a baby, you see.

Of course I never mention it to them any more,—I am too wise,—but I keep watch of it all the same.

There are things in that paper that nobody knows but me, or ever will.

Behind that outside pattern the dim shapes get clearer every day.

It is always the same shape, only very numerous.

And it is like a woman stooping down and creeping about behind that pattern. I don’t like it a bit. I wonder—I begin to think—I wish John would take me away from here!

It is so hard to talk with John about my case, because he is so wise, and because he loves me so.

But I tried it last night.

It was moonlight. The moon shines in all around, just as the sun does.

I hate to see it sometimes, it creeps so slowly, and always comes in by one window or another.

John was asleep and I hated to waken him, so I kept still and watched the moonlight on that undulating wallpaper till I felt creepy.

The faint figure behind seemed to shake the pattern, just as if she wanted to get out.

I got up softly and went to feel and see if the paper did move, and when I came back John was awake.

“What is it, little girl?” he said. “Don’t go walking about like that—you’ll get cold.”

I thought it was a good time to talk, so I told him that I really was not gaining here, and that I wished he would take me away.

“Why darling!” said he, “our lease will be up in three weeks, and I can’t see how to leave before.

“The repairs are not done at home, and I cannot possibly leave town just now. Of course if you were in any danger I could and would, but you really are better, dear, whether you can see it or not. I am a doctor, dear, and I know. You are gaining flesh and color, your appetite is better. I feel really much easier about you.”

“I don’t weigh a bit more,” said I, “nor as much; and my appetite may be better in the evening, when you are here, but it is worse in the morning when you are away.”

“Bless her little heart!” said he with a big hug; “she shall be as sick as she pleases! But now let’s improve the shining hours by going to sleep, and talk about it in the morning!”

“And you won’t go away?” I asked gloomily.

“Why, how can I, dear? It is only three weeks more and then we will take a nice little trip of a few days while Jennie is getting the house ready. Really, dear, you are better!”

“Better in body perhaps”—I began, and stopped short, for he sat up straight and looked at me with such a stern, reproachful look that I could not say another word.

“My darling,” said he, “I beg of you, for my sake and for our child’s sake, as well as for your own, that you will never for one instant let that idea enter your mind! There is nothing so dangerous, so fascinating, to a temperament like yours. It is a false and foolish fancy. Can you not trust me as a physician when I tell you so?”

So of course I said no more on that score, and we went to sleep before long. He thought I was asleep first, but I wasn’t,—I lay there for hours trying to decide whether that front pattern and the back pattern really did move together or separately.

On a pattern like this, by daylight, there is a lack of sequence, a defiance of law, that is a constant irritant to a normal mind.

The color is hideous enough, and unreliable enough, and infuriating enough, but the pattern is torturing.

You think you have mastered it, but just as you get well under way in following, it turns a back somersault and there you are. It slaps you in the face, knocks you down, and tramples upon you. It is like a bad dream.

The outside pattern is a florid arabesque, reminding one of a fungus. If you can imagine a toadstool in joints, an interminable string of toadstools, budding and sprouting in endless convolutions,—why, that is something like it.

That is, sometimes!

There is one marked peculiarity about this paper, a thing nobody seems to notice but myself, and that is that it changes as the light changes.

When the sun shoots in through the east window—I always watch for that first long, straight ray—it changes so quickly that I never can quite believe it.

That is why I watch it always.

By moonlight—the moon shines in all night when there is a moon—I wouldn’t know it was the same paper.

At night in any kind of light, in twilight, candlelight, lamplight, and worst of all by moonlight, it becomes bars! The outside pattern I mean, and the woman behind it is as plain as can be.

I didn’t realize for a long time what the thing was that showed behind,—that dim sub-pattern,—but now I am quite sure it is a woman.

By daylight she is subdued, quiet. I fancy it is the pattern that keeps her so still. It is so puzzling. It keeps me quiet by the hour.

I lie down ever so much now. John says it is good for me, and to sleep all I can.

Indeed, he started the habit by making me lie down for an hour after each meal.

It is a very bad habit, I am convinced, for, you see, I don’t sleep.

And that cultivates deceit, for I don’t tell them I’m awake,—oh, no!

The fact is, I am getting a little afraid of John.

He seems very queer sometimes, and even Jennie has an inexplicable look.

It strikes me occasionally, just as a scientific hypothesis, that perhaps it is the paper!

I have watched John when he did not know I was looking, and come into the room suddenly on the most innocent excuses, and I’ve caught him several times looking at the paper! And Jennie too. I caught Jennie with her hand on it once.

She didn’t know I was in the room, and when I asked her in a quiet, a very quiet voice, with the most restrained manner possible, what she was doing with the paper she turned around as if she had been caught stealing, and looked quite angry—asked me why I should frighten her so!

Then she said that the paper stained everything it touched, that she had found yellow smooches on all my clothes and John’s, and she wished we would be more careful!

Did not that sound innocent? But I know she was studying that pattern, and I am determined that nobody shall find it out but myself!

Life is very much more exciting now than it used to be. You see I have something more to expect, to look forward to, to watch. I really do eat better, and am more quiet than I was.

John is so pleased to see me improve! He laughed a little the other day, and said I seemed to be flourishing in spite of my wallpaper.

I turned it off with a laugh. I had no intention of telling him it was because of the wallpaper—he would make fun of me. He might even want to take me away.

I don’t want to leave now until I have found it out. There is a week more, and I think that will be enough.

I’m feeling ever so much better! I don’t sleep much at night, for it is so interesting to watch developments; but I sleep a good deal in the daytime.

In the daytime it is tiresome and perplexing.

There are always new shoots on the fungus, and new shades of yellow all over it. I cannot keep count of them, though I have tried conscientiously.

It is the strangest yellow, that wallpaper! It makes me think of all the yellow things I ever saw—not beautiful ones like buttercups, but old foul, bad yellow things.

But there is something else about that paper—the smell! I noticed it the moment we came into the room, but with so much air and sun it was not bad. Now we have had a week of fog and rain, and whether the windows are open or not, the smell is here.

It creeps all over the house.

I find it hovering in the dining-room, skulking in the parlor, hiding in the hall, lying in wait for me on the stairs.

It gets into my hair.

Even when I go to ride, if I turn my head suddenly and surprise it—there is that smell!

Such a peculiar odor, too! I have spent hours in trying to analyze it, to find what it smelled like.

It is not bad—at first, and very gentle, but quite the subtlest, most enduring odor I ever met.

In this damp weather it is awful. I wake up in the night and find it hanging over me.

It used to disturb me at first. I thought seriously of burning the house—to reach the smell.

But now I am used to it. The only thing I can think of that it is like is the color of the paper! A yellow smell.

There is a very funny mark on this wall, low down, near the mopboard. A streak that runs round the room. It goes behind every piece of furniture, except the bed, a long, straight, even smooch, as if it had been rubbed over and over.

I wonder how it was done and who did it, and what they did it for. Round and round and round—round and round and round—it makes me dizzy!

I really have discovered something at last.

Through watching so much at night, when it changes so, I have finally found out.

The front pattern does move—and no wonder! The woman behind shakes it!

Sometimes I think there are a great many women behind, and sometimes only one, and she crawls around fast, and her crawling shakes it all over.

Then in the very bright spots she keeps still, and in the very shady spots she just takes hold of the bars and shakes them hard.

And she is all the time trying to climb through. But nobody could climb through that pattern—it strangles so; I think that is why it has so many heads.

They get through, and then the pattern strangles them off and turns them upside-down, and makes their eyes white!

If those heads were covered or taken off it would not be half so bad.

I think that woman gets out in the daytime!

And I’ll tell you why—privately—I’ve seen her!

I can see her out of every one of my windows!

It is the same woman, I know, for she is always creeping, and most women do not creep by daylight.