Voices at Thirteen

“I think I’d be more excited at getting the new voice than sad at losing the old one”

Cathedral chorister, aged thirteen, 2016.

“To be honest . . . I just, I only really sing high when I’m happy. . . I’m not one of those choristers you test so I’m not based on the high notes”

Youth choir member, aged thirteen, 2014

Introduction

According to John Cooksey, a boy’s voice is most likely to reach its “pinnacle of beauty, power and intensity” during Y6 [US grade 5] (Cooksey, 1992: 55). Superficially, this agrees with Aled Jones’s observation that boys’ voices have a crystal-clear quality a year before they break. It does not agree so much with David Flood’s experience that Y7 (11 – 12) is that the “golden year”, still less with Andrew Nethsinga’s assertion that “boys’ voices tend to reach their peak around Year 8 (12 – 13).” A cathedral choir in which Y6 (age 10 – 11) is the top year has never been the experience in the UK. Moreover, if for some two thousand years boys have on average been “apt to change their voice” on turning fourteen, we are talking about Y9 (13 – 14). There is some explaining to do here! The necessary theory has been covered over the previous three chapters. In this chapter I am going to explore the conundrum through some of my case studies.

Cooksey’s statement refers to the unchanged voice shortly before it begins to change. The singing range at this time he gives as A3 – F5+ though this is of limited relevance here. If a boy identifies as a soprano or “treble”, he will contrive to sing in the range of that part if he possibly can regardless of how far he is through puberty. For this reason, growth velocity supported by voice deepening velocity is the better guide. That is why growth velocity is the primary variable in my longitudinal studies. Cooksey gives an average SF0 range of 220 – 260 Hz for the unchanged voice. This wide range underlines how necessary it is also to monitor SF0 over time and derive a voice deepening velocity. A single SF0 sample can be quite misleading for an individual case.

Cooksey’s “pinnacle of beauty, power and intensity”, though a qualitative description, is supported by hard data in the form of spectrographic display. Jones, in contrast, uses the word “break” to refer to the time he gave up singing soprano. As we have seen, a boy can be at any one of a number of different stages when he gives up soprano. The nearest we get to anything more informative from Jones is when he says, “it was hard to tell exactly when it broke; my voice never actually did that squeaky thing where it goes high and low at the same time.” That “squeaky thing where it goes high and low at the same time” is most likely the midvoice IIa or stage 3, which places the “break” well past Y6 for most. In Jones’s case, it was Y11 (age 16).

Study sample and protocol

My records of boys’ growth and voice change date from 2006. Longitudinal work is still in progress today (2023). During this period I have recorded the voices of over a thousand boys. Most of these have been speaking voices only, though a little over two hundred boys have completed the following protocol:

- Counting slowly backwards from twenty (the numbers between five and twelve being actually sampled)

- Reading the opening paragraph of the Arthur the Rat phonetic speech passage

- Singing the tune of “Happy Birthday” to an alternative set of words with vowels chosen for analysis and at a pitch intuitively selected by the singer

- Glides across the entire range from top to bottom and bottom to top

- Pitch matched scales ascending and descending

- Five note vocalises across known lift points in the voice

- Successive messa di voce ascending across the range at intervals a third apart.

Completion of this protocol once by boys studied cross-sectionally has resulted in useful supplementary data, but by some margin the most powerful data come from boys studied longitudinally, in most cases at three monthly intervals. Only longitudinal studies allow growth velocity to be computed and monitored. Possibly uniquely, these have been longitudinal field studies. Most longitudinal studies are of a single and particular cohort. The field work approach means that boys from a variety of different choirs have been visited in their own homes or sometimes schools. Where possible, longitudinal cases have been followed through beyond voice change, sometimes into young adulthood.

Ethical approval for all the work was granted by the Edge Hill University ethics committee according to the Helsinki declaration. All the usual processes of informed consent, anonymity, right to withdraw and ownership of data have been followed. Parents have acted as chaperones during home visits. Where visits took place in schools or choir rehearsal rooms, a suitable second adult was appointed by the organisation.

The convention of using pseudonyms has proved challenging. I prefer pseudonyms to appellations such as “Boy A” which I find too depersonalising. What makes it difficult is that whatever name I choose as a pseudonym for one boy will be the real name of another in the study. So, the pseudonyms have been chosen from lists of unusual boys’ names which the average parent would be unlikely to choose. Where a boy’s work is in the public domain and perhaps well known, I have allowed the option of using the real (given) name at the family’s discretion. Where a real name is used, the fact is stated in parenthesis. All other names are pseudonyms.

Friendship Groupings and Growth

Until recently, the practice in British ecclesiastical choirs has been for all boys to be “treble” until it is decided that their voice has “broken”. The case studies later in this chapter give some insight into the anomalies that can arise as a result. First, I want to look at two boys in the same secular youth choir. Such choirs are more likely to be attentive to the intermediate vocal range approach proposed by Irvine Cooper and endorsed by Cooksey’s later research. Superficially, this presents as perhaps the safer practice, but it is not without its problems.

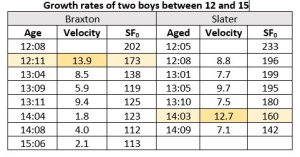

Frederik Swanson was amongst the first to stress that the rate of change could vary quite significantly from one boy to another. The table below shows the progress of the two boys from the time of joining the choir at age twelve. They had been good friends since childhood and the friendship continued throughout their time in the choir. As is almost invariably the case, both progressed through all the puberty stages, but differed in the length of time spent at each stage. It is important to stress that both were entirely “normal” children and grew up to become entirely normal “adults”. Both had healthy BMIs and did not differ significantly from each other in height or weight. The critical difference of their adolescence was the time each reached peak height velocity (PHV). Braxton reached this relatively early by age 12:11, but PHV for Slater did not come until age 14:03.

This is directly reflected in the deepening rate of their speaking voices, as can be seen in the right hand columns. A pitch of 233Hz suggests an unchanged voice for Slater at age 12:05, whereas Braxton at a similar age was already well into midvoice, experiencing the full transition to baritone between 12:11 and 13:04. Slater had reached midvoice by 12:08, but remained there right up to around his fourteenth birthday.

The boys’ close friendships presented the conductor and choir manager with a dilemma. Should the boys be allocated to parts strictly by vocal criteria, or should friendship groupings take priority? Rightly or wrongly, they made the decision that the boys’ friendship groups should take priority over groupings formed through voice assessments. The consequence was a period of several months (a whole choir season in fact) when Slater sang a part range not matching his voice, assuming a vocal identity that was not his. He is the source of the quotation at the head of the chapter.

What part do you sing?

Er, I think I sang Cambiata II but, I sometimes went to the, like EBs,

the, is it extended baritones or . . . ?

Emerging baritones.

Emerging baritones. I find that much easier because I sing tenorYou sing tenor?

Yeh.

Right, OK. Well, I’m going to have to tell you something

that you might not totally like to hear.

Yeah? [long, drawn out, sounds apprehensive]

Your voice is still treble. So the lowest part you should be

singing is Cambiata I. Now, [pause] what do you think about that?

[Sighs and snorts] To be honest . . . I just, I only really sing high when

I’m happy and (pause) . . . well . . . well if the lowest part I can sing is

cambiata, how come I sing in the tenors at my choir?Well. I think you can’t be singing tenor. Whatever you’re

singing it isn’t proper tenor. We’ll do some vocal exercises in a minute….[indistinct groan-like sound]

The whole conversation, recorded at age 13:01, is reproduced on pages 130 – 132 of Contemporary Choral Work with Boys.

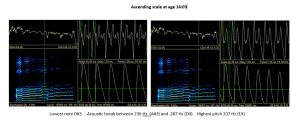

The following illustrations are from Slater’s later assessment at age 14:03. The best part match to his voice at this time was cambiata II (E3 – E4). A conductor who is prepared to audition individual boys carefully should have had little difficulty in determining that Slater was still not a tenor and still not ready to join the emerging baritone section. He could not reach C3 in any of the tests, ascending or descending. Voice source and acoustic display software can tell us more about what is happening. The figure shows an ascending scale from the lowest note Slater could clearly phonate, which was D#3.

Importantly, we can see that there is an acoustic transition between A#3 when higher partials are lost and D4 when the voice regains stability. There is no evidence of a laryngeal break. CQ was 50% before the acoustic transition and 49% after it. The whole singing range is in M1 phonation. Slater could not get beyond E4 in M1 when a laryngeal break did occur, throwing the whole voice into chaos.

Slater did, by this time, have a potentially strong M2, but this had never been used or developed for singing (“I’m not one of those choirboys you test . . .”). This is shown in the next two figures.

Slater was asked to glide upwards but chose to glide back down as well. In a previous down glide starting in M2, the laryngeal break occurred on D4, but on the up glide here it is somewhat lower at A#3. The M1 range here is limited, but the M2 reaches A5.

This was an “ordinary” voice, typical of what might be expected from a boy who sings in a good school choir. It had never been developed to a “peak performance” level, nor could it have been unless Slater had been counselled to remain in a higher part range.

Peak performance after the first growth spurt

How Aled Jones managed to pass through stage 3 without the “squeaky thing” was never adequately researched or documented. However, several of the boys I have studied have experienced something similar. We will see how shortly. However, I wish to reiterate the fact that very few (if any) of the performances I have studied have been by boys with unchanged voices. One reason for this is that few boys of nine or ten have the musical experience and training level necessary for a peak performance.

In this section I am going to begin with some performances that occurred during the first growth spurt. This, it will be recalled from Chapter 3, marks the transition from peripubertal to “in-puberty” and is associated with the SF0 (average speaking voice pitch) falling from below 220 Hz to around 190 Hz, with 200 Hz being associated with the medical onset of puberty.

Taking the “solo of particular importance” definition of a peak performance, the famous Once in Royal David’s City solo performed to a congregation of nearly two thousand in Liverpool Cathedral might qualify for Max (real name), aged 11:11, and midway through David Flood’s “golden year” (Y7) at the time. Max was chosen for the solo presumably because his was what his choir director considered the best voice available on the day and he could be trusted to hold his nerve during quite an auspicious and perhaps intimidating occasion.

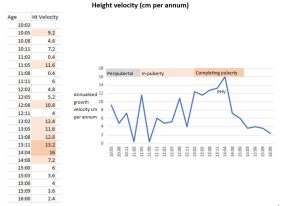

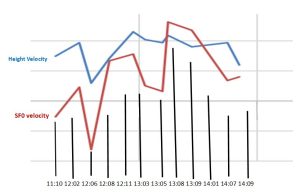

Max has been the most comprehensively documented of my case studies, being examined longitudinally at monthly intervals between the ages of ten and sixteen. The figures below show his height velocity over this period.

We can see from this some key milestones. Just before his eleventh birthday there was a dip in the growth rate which presaged a period of accelerated growth characteristic of “in-puberty” until just before his thirteenth birthday. There was then another dip which presaged a clear acceleration to the PHV (peak height velocity) of completing puberty. This is reached by age 14:04. SF0 at the time of the Once in Royal solo was 212 Hz, a value associated with the threshold of pubertal onset, but well below Cooksey’s suggestions of 220 Hz – 260 Hz (unchanged) or 220 – 247 Hz (midvoice I / stage 1).

Unfortunately, the Once in Royal solo was not recorded but the two CD tracks below were recorded a month either side of it.

Britten Ploughboy

Schumann Aus altern

What happened to Max subsequently is a matter of considerable interest and we shall return to it shortly. First, I want to look at another peak performance at the same stage of growth. Empty Chairs at Empty Tables from Les Miserables was recorded by Cormac (real name) at the age of 12:05 and released as a music video. Cormac, at this time, according to regular measurements made by the school nurse, had just undergone the same initial growth spurt as Max had at age 11:11.

He had recorded an album for Decca at age 11:05. School medical records indicate that growth had been at the prepubertal rate up until age 11:00. From this we might conclude that the Decca album was recorded at the very end of the unchanged stage – exactly when Cooksey considered the voice to be at the pinnacle of beauty, power and intensity.

Several other tracks were recorded at the same time as Empty Chairs (range A3 – G5) but the music video reveals a passion and maturity of performance not found in any of the performances given prior to the growth spurt. The reader is invited to compare performances before and after the initial growth spurt here and judge perceptually whether increased maturity and experience compensates for any of the possible losses described by Cooksey.

Gaelic Blessing

Empty Chairs

Cooksey’s clear description that there is “variable loss of tonal clarity and richness in the higher pitches, most notably in the C5 – F5 range” (Cooksey, 1992: 52), though well supported by spectrographic evidence, is at odds with the perceptual quality of Empty Chairs and many other recordings made by boys at similar stages of voice change.

Weinrich et al noted the following in their study:

Breathiness significantly increased as the boys progressed from Stage 1 through Stage 4. Breathiness was shown to be more significant than timbre and voice quality. This is in contrast to Cooksey’s work which does not consider breathiness as the prominent salient feature (Weinrich et al, 2020: 141).

Cooksey did note that an increase in breathiness accompanied the decrease in upper partials on progression to stage 1, but the observation that this is “more significant” than timbre is a consequence of the statistical analysis of the Weinrich judges’ perceptions. The perception of breathiness was statistically significant whilst the perception of timbral changes was not.

It is possible that the relative ease with which we can now obtain voice source measurements has alerted us to the obvious relationship between breath noise and CQ. There are two opposing dynamics here. On the one hand breath intrusion decreases with training (Barlow and Brereton, 2008) but on the other it increases as a result of pubertal disruption to the larynx (Weinrich et al op. cit.). In the previous chapter we considered how highly trained boy trebles at stage three retain a “head voice” sound through a relatively high CQ, at the probable expense of phonational efficiency.

Acoustic display software can help us here. The spectrograms below show downglides by Max at ages 10:02 and 13:04. At 10:02, there is a pure band clear of breath from A#5 down to G3, a good treble range, though there is a pitch break and some breath intrusion as the lower limit is reached. At 13:04, the SF0 had descended to 176 Hz and PHV growth spurt was just beginning. We can see that the treble range is still there, but at the expense of breath intrusion as Max attempts to adjust to the laryngeal growth of puberty.

A key question would be the extent to which this is perceived in singing. At age 13:04, Max had reached a critical stage. I drew attention in earlier chapters to the confusing situation for parents when a boy is told he has a changing “cambiata” voice by a secular youth choir but an ecclesiastical choir tells him he is still a treble. For Max’s regular demonstration recordings I had determined that the treble phase was over and we had begun to explore alto repertoire. He was by this time singing alto with the National Youth Choir of Scotland (NYCOS) National Boys Choir. At the age of 13:03, we recorded the alto verse part of Tomkins’s My Shepherd is the Living Lord (range G#3 – G4) and at the age of 13:06 the traditional song Love Will Find Out the Way at cambiata pitch (range E3 – E4). By 13:06, SF0 had fallen to 158.4 Hz.

Tomkins Living Lord

However, during this period he was singing regularly with the RSCM Northern Cathedral Singers (at that time, all male) where he remained a treble. The conductor had no reservations about boys’ changing voices. Repertoire included Widor’s Surrexit ad Mortius, which has a particularly high soprano tessitura against the background of sustained loud organ accompaniment, and the similarly loud and high Dupre Laudate Dominum. During the service in which this was sung, Max was asked to sing the verse part of the Wise in F canticles. He was aged 13:03 at the time with SF0 186 Hz. More significantly, his growth velocities were, between ages 13:02 and 13:04 cm/annum, and between 13:04 and 13:06 cm/annum.

Love Will Find Out the Way and Wise in F can be compared perceptually here:

I would imagine that most singing teachers would have little hesitation in judging the first to be modal voice and the second to be falsetto. However, given what we have said about boys not being miniature men and the protracted time it takes the vocal ligament to mature, to what extent is the Wise in F truly falsetto (i.e. M2 with flaccid TA) is a question that might send us to display software.

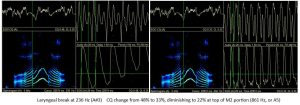

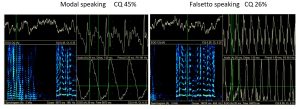

The figure below shows extracts from the phonetic passage Arthur the Rat. Recorded at age 13:04, on the left in normal modal speaking voice and on the right in imitation of my own falsetto voice. CQ has fallen from 45% to 26% and the glottal curve has lost its gentler opening slope to assume a more symmetrical or sinusoidal shape.

Max was the asked to sing the note G4. The figure shows a similar glottal wave pattern to the falsetto speaking, but the CQ has increased from 26% to 46%.

This could well be because when asked to go into “singing mode” he has instinctively tightened his lateral crycoarytenoids, resulting in a hybrid phonation as described by Williams (2010: 277 and 299). This type of phonation is unlikely to survive beyond stage 3. I continue Max’s story across stages 4 and 5 later.

Cormac’s experience was in complete contrast to this. He gave a peak performance at age 12:07 when he performed the Bach/Gounod Ave Maria at the BBC Chorister of the Year competition and another at age 12:10 when he sang an acclaimed arrangement of Run in Britain’s Got Talent. This period almost exactly spanned his beginning the in-puberty phase. Growth velocity between 12:03 and 12:06 had been 2 cm/annum (a pre-spurt dip) and between 12:06 and 12:10, 9 cm/annum (a clear spurt) which coincided with voice deepening reaching the 200 Hz landmark.

Although this was shortly before he began working with me, he had become aware that his voice was changing. He posted a Youtube video he had made at age 13:02 during another studio recording session with the pianist Dominic Ferris.

It feels like yesterday since we were last here, not eight months ago, although I think I’ve grown a bit and I can’t go as high as I used to, which is a bit annoying. But we’re here because we’ve got to capture my voice before it changes and it’s in its prime at the moment. Some notes I can’t hit because they’re a bit too high. But it still, we’re getting to sing a bit more lower now.

A month later, at age 13:03, he gave a live outdoor performance of Run. Although he brought it off to a delighted audience, his mother reported that he had been struggling with the high notes in a way he had not during Britain’s Got Talent. By this time Cormac was forming a clear view that he did not want to sound like a choirboy. Run, rather than Ave Maria , was the direction he wished to take.

His treble “swansong” was a performance of Rutter’s Gaelic Blessing in the Royal Albert Hall at almost age 13:08. He was now developing a laryngeal break around C5/D5. This had not troubled him during the recordings made at 13:05 but the wise decision to steer clear of it pushed the RAH performance into the key of Ab, a minor sixth lower than the original unchanged voice recording at 11:05. Height velocity between 13:07 and 13:09 was 7.1 cm/annum and between 13:09 and 13:11, 6.8 cm/annum. Critically, SF0 fell from 185.7 Hz to 157.5 Hz between 13:07 and 13:09. The Albert Hall performance occurred therefore in the middle of a significant spurts in both height growth and voice deepening.

The series of spectrograms of highest to lowest glides allow us to see what is happening.

The vertical cursor marks the point at which a laryngeal registration shift occurs. At age 13:07, there is barely any M2 phonation at all. Two months later, the break point has moved down about three quarters of a tone, but the range of new M2 phonation above it has increased and extended upwards. Cormac’s total range, in other words, is expanding, potentially in the way predicted by Henry Leck. By 13:11, the laryngeal break (“clunk” for Leck) has shifted significantly down to what we introduced in the previous chapter as the “devil’s note”, midway between D#4 and E4 – a “textbook example”.

Below the devil’s note, Cormac at age 13:11, had the beginnings of his new baritone voice. In pitched scales, he could just phonate C3, but only weakly. Eb3 to Eb4 was his secure singing range – again a “textbook” cambiata II, exactly what we would expect from a boy at the end of stage 3. However, above the devil’s note, Cormac now had a good M2 treble. By age 14:02, this had further strengthened to the extent that he could sing the Stanford in G Magnificat solo with a more than pleasing tone. This, however, he was prepared to do only for fun at the end of his assessment session. He was adamantly opposed to anything that would make him “sound like a choirboy”, proud of his ability to phonate C3, and eagerly focused on the development of his new voice.

I will continue the stories of both Max and Cormac in the next chapter when we look at middle adolescence and the completing puberty phase. First, we must take a further look at the stage 3 and 4 choirboy.

All English boys are trebles

Cooksey had the following to say about part assignment:

Unchanged Voice: Usually sings soprano, but also capable of singing soprano II or alto.

Midvoice I: Usually sings alto in SATB music, but still has the most desirable vocal colour and power in the midrange area [B4 – C5] (Cooksey, 1992: 55-56)

In Chapter 3 I referred briefly to the important work of Michael Fuchs in Leipzig. In Fuchs’s three phase scheme, planning for leaving the soprano/alto section should take place during the “premutation” (stages 1 and 2 for Cooksey), and some boys who had previously been sopranos might move to alto at this time. There is nothing at all unusual about this throughout mainland Europe, but in England the curious belief that “all boys are trebles” regardless of the pitch of their voices came to dominate the twentieth century and largely continues to this day. This is partly because in most professional choirs adults are preferred for the lower parts, whereas in Germany, the United States and most other countries, adolescents can be found on the lower parts in choirs of similar standing.

It has not always been so. In later chapters, we look at English boy altos of the nineteenth century and boy means of the sixteenth century. Now, I am going to look at an English cathedral chorister who, like many of his fellows, could have been an alto but remained as a “treble” until his voice finally “broke” at age 14:09.

William, who became head chorister at a cathedral in the north of England, was studied longitudinally from age 11:10 to age 14:09, with a follow-up at age 15:10. The figure below shows his height velocity and voice deepening velocity over that period.

PHV was reached at age 13:03, with peak voice deepening velocity following five months later at 13:08. Between the ages of 12:11 and 13:03, William’s SF0 fell from 213 Hz to 196 Hz, a change that would place him into Fuchs’s premutation phase when movement to alto might be considered and planning for leaving the soprano section within six months should begin. During the same period, his growth velocity accelerated from 7.1 to 11.5 cm/annum which indicates fairly intense puberty.

At my suggestion, a recording session was arranged to capture William’s “treble” before it was finally lost. This took place at age 13:05, by which time SF0 had fallen just a little further to 192 Hz though 2.2 cm had been gained in height between 13:03 and 13:05, which is a rapid tempo. William chose some of his favourite pieces, which included Britten’s Corpus Christi carol which can be compared with an earlier recording of Suo Gan, made during his first session at age 11:10

Suo Gan, age 11:10

Corpus Christi Carol, age 13:05

Which of these might be closer to “peak performance” is a subjective matter unless one takes the view that a peak performance is impossible once voice change has set in. Objectively, though, the pieces recorded at 13:05 were far from being “swan songs”. William continued as a “treble” until his final service at age 14:09. At age 13:08, he took part in a BBC Radio 4 programme when the presenter, Christopher Gabbitas, described the voice as naïve and child-like in comparison to a 1932 recording of Temple Church chorister Denis Barthel, aged 16 at the time. Barthel would have been singing with a stage 4/5 M2 “head tone”. William had not been trained to do this, which may explain the discomfort he was feeling by age 14.

The last full assessment was at age 14:07, by which time SF0 had fallen to 145 Hz. Between the ages of 13:09 and 14:07, the significant spurt in weight growth had occurred (see Chapter 3). William was now experiencing strain and discomfort as a treble.

His own words here are important:

MA: Why did you carry on? Tell us about your last few months in the cathedral choir.

W: Well, the main reason was for the pure enjoyment of being in the choir. The time that I was in it, it was always enjoyable. I wanted that to go on for as long as it could, because although it was a strain to keep singing every week, the enjoyment of it I wanted to prolong for as long as I could because I could still just about sing if I strained.

Moving a boy to alto is rarely an option in an English cathedral choir. However, I was keen to find out what would be the consequences of changing to alto. At age 14:01, I persuaded him to record as an alto for his regular demonstration piece. We chose the verse part from Gibbons’s well-known This is the Record of John. The £5 tessitura test at this session had been completed in the key of E4 (B3 – B4) in a voice that sounded perceptually falsetto (certainly in comparison to the speaking voice). The sound samples allow a perceptual comparison to be made between the Gibbons, which sounds modal, and the B3 – B5 tessitura test, which sounds distinctly more falsetto in comparison. Personally, I felt the Gibbons had been a success. On the day, William thought it was “brilliant”, “weird” and “good fun”. However in his later interview at age 15:10 he appeared amused on listening again to the recording, insisting that only an adult countertenor should sing the part because it was “written for a man” (see chapters on historically informed performance!).

Tessitura test ( B3 – B4)

This is the Record of John

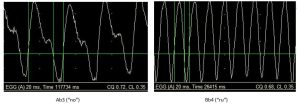

EGG recordings allow us to see what is happening at the voice source. There were small acoustic breaks in scales and vocalises but William covered these well. No clear laryngeal breaks could be identified in any of the tests during this session. The left hand EGG is the word “no” (Ab3) at the end of the phrase “and he answered no”. The right hand EGG is the highest note in the piece the “ru” of Jerusalem on Bb4.

The CQ is a healthy 72% on the low Ab which shows a clear, modal waveform, including adult-like “knee”. William manages to maintain almost the same CQ (68%) on the highest note, which would explain why it does not sound obviously falsetto. A hybrid phonation typical of a stage 3 chorister is probably the best explanation.

A Three Choirs swansong

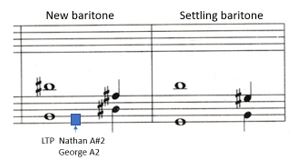

The annual Three Choirs festival occurs during the summer months. For the oldest boys participating, the festival can be a swansong since they will not return to choir in September. Nathan left at the end of Y9, by which time he was aged 13:11, whilst George left at the end of Y8, aged 13:03. Measurements of speaking voices and lowest singing notes for both boys by this time were consistent with data given by Cooksey for the new baritone stage.

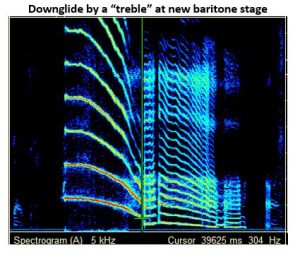

Shortly before the assessments took place, George had sung the Stanford in G Magnificat solo (range F#4 – G5). This is so far above the baritone range that it could only be sung in M2 with a flaccid TA. Figure 9 shows a downglide by George. He was asked to begin on a “high treble note”. His starting pitch was 777Hz, almost G5. A laryngeal break into modal voice at 304 Hz (approximately D#4, the “devil’s note”) seems quite clear. According to catastrophe theory, George might have been in danger of a fatal “crack” in the middle of the Stanford. However, the lowest note in the Magnificat is F#4, three semitones clear of George’s “devil’s note” showing as D#4 in the spectrogram.

George was able to perform the tessitura test without obvious difficulty equally in his M1 baritone range (C3 – C4) and in his M2 treble range (F4 – F5). He recognised these as “two separate things almost” and did not complain of any strain or discomfort in either voice.

Which of those voices do you prefer?

I’m not sure. Probably the bottom one. If I had to choose. But I don’t really mind.

Nathan in the same choir, had recorded all three SSA parts of Mendelssohn’s Lift Thine Eyes by multi tracking at the age of 13:09. The soprano part ranges up to F#5 and the alto part down to A3. All three parts were managed without difficulties of crack or break.

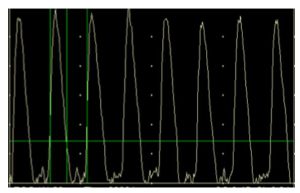

In testing two months later, Nathan was asked to sing “a clear treble note”. He chose A4 (440Hz). He was then asked to glide downwards from that note. The same phonation was sustained as far as 202Hz, meaning that Nathan could (as he did) have managed all three parts of Lift Thine Eyes without any laryngeal registration shift. The figure below shows a descending glide from the A4. On the left, the CQ is 44%. This is probably representative of the way Nathan was singing “treble” at this time. He did not “break” into an M2 baritone. What we can see on the right is how the voice simply disintegrated below G#3 into what might be described as a “treble fry”. CQ is now only 23%.

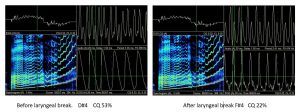

This is not commonly found and may be the consequence of Nathan not using any M1 registration for the “singing voice” of his final year in the choir. I then sang a tenor C and asked him to copy it. He did this with ease in a clear baritone voice with a CQ of 51%, next singing a five note vocalise in the same baritone. I then asked him to sing an ascending scale and to keep going even if the voice “broke”. The result is show below. On the left is the baritone with the cursor near to D#4. CQ is 53%. On the right, the cursor is at F#4, the first settled note after the break. The CQ is now only 22%. This “falsetto” is not Nathan’s “singing voice” which, as we have seen, has a notably higher CQ provided he starts in his “treble” range and does not go near the baritone. The break was across the “devil’s note” of E4, so in that sense Nathan is completely “normal”. He could, like George, have sung the Stanford in M2 with little danger of a “crack”.

Use of the baritone M1 voice for singing was a new experience for Nathan that caused some consternation. Matters came to a head when he was asked to perform the self-selected tessitura test. He began immediately after counting backwards from twenty on the approximate note E3, so he was already in M1 and experienced the inevitable crack on the “devil’s” E4. The tale is best told using his own words from the transcript.

MA: The key you chose, was it a good one?

N: No

MA: Why wasn’t it a good one?

N: Because it was on the voice break.

MA: It was. Choose another key that avoids that problem,

N: Hums Db3 and begins in that key. Flips to falsetto on the octave leap (Db4)

N: Oh f***! (much laughter)

MA: What are you going to do Nathan? you’re in a tight corner here!

N: Begins again in M2 on E4 and is successful in range E4 – E5. Sounds “falsetto” and he is clearly not happy.

MA: Actually Nathan, sing it boldly.

N: I don’t know, I don’t know. (sounds worried)

MA: That key that you just chose, as though you were in the cathedral, in a concert, and you’ve got to do it properly, sing it in that key now.

N: Sings again in a clear treble that sounds “head voice”

MA: Brilliant!

N: I hate my life.

Crucially, it is the request to “sing it boldly” that increases the CQ and transforms the timbre from a voice that sounds “falsetto” to a voice that sounds “head”.

Nathan recorded regularly from his choir audition piece to his final treble swansong, which allows us to make perceptual judgements. The same piece was recorded at age 09:04 (Y5) when the voice was unchanged and at age 12:09 (Y8) when the voice had reached stage 3.

Look at the World, 09:04.

Look at the World, 12:09.

Identity change at audition

There is ample evidence that before the Second World War boys regularly sang soprano for some years after their speaking voices had settled in the new baritone register. It is difficult to disentangle the perceptual evidence of their singing from the evidence that puberty either began later and/or took longer to complete once it had begun. It is an interesting question and the genesis of my 2009 title, How High Should Boys Sing?

There are grounds to believe that without present day social pressures and normative expectations of how high teenage boys should sing, the period of post-puberty soprano singing could have been longer than it was for George and Nathan, had either of them willed it. One phenomenon that requires explanation is why William, who wanted to “prolong it for as long as he could” was unable to continue as a treble beyond the age of 14:09, more on account of strain and discomfort than social pressure. Voice science has provided us with an answer in William’s case. Phonation at treble pitch decreases in efficiency throughout stage 3. This does not explain the longevity of the pre-war boy sopranos who sang past that stage. Our next case may go some way to doing that.

Cardean (pseudonym) had arrived for a national youth choir audition having prepared Handel’s Where ere you walk, which he rendered in a full soprano voice. The conductor was concerned about this as the boy’s speaking voice was clearly a deep baritone, so he sent me the recording for a second opinion. The tone had a strong, pure, and fluty quality with natural vibrato quite unlike the expressionless falsetto of a boy who normally sings in M1. Cardean reported “no strain or discomfort” and his performance was indeed musical, well-controlled and by no means without merit. I perceived my task as to acquaint him with the facts of puberty and voice, and to obtain as much data as I was able about how he was actually singing. How he should sing after that was between him and the conductor. The result of this was that he decided to reaudition (successfully) as a baritone.

He was at the time one month short of fourteen with height and weight within the range for boys completing puberty and an SF0 of 107 Hz. This put him comfortably beyond stage 3, so there was a good opportunity to explore fully with the aid of Voce Vista how a good soprano voice was being produced by a boy whose new voice was of a deep baritone or even bass quality normally associated with stage 5. The first displays show his normal M1 voice, on the left, reading the Arthur the Rat passage and on the right, singing the note A2. CQ is similar at 43% speaking and 40% singing. The sung note has a full spectrum with good resonance in the 3 – 5 kHz band.

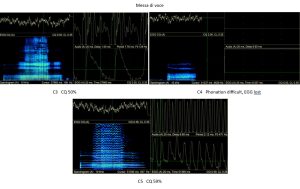

The tessitura test was sung confidently and without the slightest hesitation in the key of A4 (E3 – E5). In pitched scales a highly extended range from E2 to C6 was demonstrated. Whether ascending or descending, there was a difficult break at C4 where a clear perceptual change took place, reflected in the acoustic (spectrographic) display though not in the EGG. CQ was 44% above the break and 42% below it. This was explored further through messa di voce on C3, C4 and C5. These are shown below.

The mere fact that a messa di voce of the quality shown was possible on C5 suggests that this was has been called adolescent “head tone”, not the crude falsetto of a boy whose voice has recently changed. Moreover, the CQ had actually increased in the soprano range, from 50% to 59%, suggesting that this was practised and accomplished singing. The decision to terminate the soprano voice looks to have been a cultural rather than physical one. This is what makes the question How High Should Boys Sing? such an interesting one once voices change. In interview, Cardean revealed that his reasons for developing the soprano persona were social and practical. He had reached puberty earlier than most other boys in his year and found this difficult.

You’ve actually got a deeper voice than other boys in your class? Is that right?

Yeah.

And when you said to <conductor> that you’d sing Happy Birthday, your voice could actually be lower than the other boys? Is that what you were saying?

Uh huh.

And would you find that…

I find it a wee bit awkward, due to the fact that everyone just looks at me

What, for singing in a lower voice?

Yeah.

So by singing in a higher voice you’re more like the other boys? Is that what you’re saying?

Mmm.

Conclusions

The other case studies in my longitudinal database tell broadly similar stories to the ones selected for this chapter. The common thread is they are all stories about adolescence, about boys either “in” or “completing” puberty. There are, of course, unchanged “treble” voices in choirs but unless they are truly exceptional ones, they are unlikely to give the “peak performance” of their career. From Aled Jones to Andrew Nethsinga, there is agreement that it is boys of secondary school age who give us memorable “treble” performances. At one level, this is easy to understand. It is boys in Y7 upwards who have developed the necessary musicianship, intellectual maturity and physical control that is lacking in most children of primary school age, certainly those below Y6. If, however, nearly all of these secondary age boys have changing voices as a result of beginning and progressing through puberty, the matter becomes more difficult. John Cooksey’s view of the “height of the prepubertal period”, the unchanged voice reaching the “climax of beauty and fullness” towards the end of Y6 (US Grade 5) does not sit easily with Peter Giles’s view that “boys of 13 have a stronger voice: more plangent, more sonorous, more resonant”.

This chapter has lent support, somewhat reluctantly, to the Giles camp. I say “reluctantly” simply because Cooksey’s work is so thorough, so widely respected, and upheld even by the very case studies described in this chapter. It is the visualisation software that has been used that confirms a decline in vocal efficiency beginning with the onset of puberty, yet the ears of many musicians of experience and indeed eminence have long preferred the sound of boys who are technically likely to be singing less efficiently. This chapter, however, has gone beyond that point in drawing attention to the kind of singing that is possible once an adolescent has developed a strong M2 phonation. Catastrophe theory can predict a humiliating “crack” or even sudden “break” in performance. This does sometimes happen but can be avoided by a singing range that does not come too near to the point at which a laryngeal registration break might occur. This was demonstrated by several of the case studies. Ultimately, it is up to a suitably knowledgeable singing teacher to give good advice. In the next chapter I tell, in their own words, the stories of boys in middle adolescence who are in a position to reflect on treble careers recently ended and future careers hoped and planned for.

Key points to take away from this chapter include:

- Unchanged voices have only one, continuous register. At low pitches, the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles are more dominant, whilst at high pitches the crycothyroid (CT) muscles are more dominant, but there is no laryngeal break between an M1 and M2 mode of phonation as there is in adult male voices.

- As puberty progresses, separate M1 and M2 registers begin to develop. At first, the M2 register is small in range, weak and unstable, but it increases in strength and stability until it reaches the point at which a good soprano range from about D or E4 to F or G5 is possible in the M2 register only.

- The closed quotient (CQ) plays a critical role in the quality of the soprano/treble voice. At the onset of puberty, this decreases in most boys as the vocal folds grow erratically and control becomes difficult. The tone becomes breathier and weaker in harmonic content.

- Boys who sing regularly and develop high levels of skill are able to maintain a higher CQ which results in the strong treble “head” tone of boys in puberty, typically those in Y7, Y8 and sometimes Y9.

- Boys who sing less intensively usually remain in the modal voice and break into a weak, expressionless falsetto somewhere between C4 and F4, most commonly around E4. CQ can then be very low.

- Singing styles that rely mostly on the modal voice result in TA dominance which can turn into forced or strained “chest voice” quality tone and result in a “breaking” of the voice at relatively early ages.

- Singing styles and vocal practices that strengthen the CT muscles can defer the “breaking” of the voice when singing, although the speaking voice is largely unaffected.

- Visualisation software such as Voce Vista helps us to see what is happening when our ears might deceive us. The voice source (EGG) display that shows CQ and the acoustic (spectrogram) display that shows the degree of air turbulence, the relative strength of higher harmonics are particularly useful when boys’ voices are changing. It can also be useful to identify the frequency bands of the first four or five formants.